Wolastoq

The Wolastoq (transl. Saint John River; French: Fleuve Saint-Jean) is a river flowing approximately 418 miles (673 km) from headwaters in the Notre Dame Mountains near the Maine-Quebec border through New Brunswick to the northwest shore of the Bay of Fundy. The river and its tributary drainage basin formed the territory of the Wolastoqiyik and Passamaquoddy First Nations prior to European colonization. As the longest river between Chesapeake Bay and the Gulf of Saint Lawrence the Saint John offered one of the best transportation corridors for First Nations refugees to retreat from the English colonization of North America's Atlantic coast. The Wolastoqiyik and their Acadian allies retreated upstream after English victories in the French and Indian War to establish the Republic of Madawaska on the remote upper river. Inhabitants of the upper river rejected both Canada and United States sovereignty until the present Canada–United States border was established by the Webster-Ashburton Treaty of 1842. The lower river has been developed for agriculture and industry, while the United States portion of the river upstream of Madawaska remains the sparsely populated North Maine Woods. The historic isolation of Madawaska has helped preserve the Acadian French dialect.

First Nations

The eastern Algonquin languages had different dialects associated with each of the major river systems of New England and the Maritimes; and there was often a linguistic bifurcation between residents of the upper river and those living along the coast and tidal estuary.[1] The Passamaquoddy hunted sea mammals along the northwest shore of the Bay of Fundy while speaking a mutually intelligible dialect with the Wolastoqiyik who were inland hunters along the upper Saint John River and its tributaries.[2] The Wolastoqiyik identified themselves as inhabitants of the river their canoes traveled for hunting, fishing, and trading.[1] Early 16th century fur trade with French fishermen encouraged increased interest in the smaller tributaries and headwaters where scarcity of edible prey kept population density low.[3] After spending the winter hunting and trapping in the interior, the villages of Ouigoudi at the mouth of the river and Aukpaque at the head of navigation were summer gathering places accessible to European fur traders.[2] Fur traders brought European diseases reducing the estimated Wolastoqiyik population to less than a thousand by 1612, but the fur traders' contribution to the First Nations gene pool would provide some disease resistance. No pure blooded Wolastoqiyik or Passamquoddy survived the 20th century.[2]

European colonization

Rivalry between English and French fur traders pre-dated colonization of North America.[3] Ouigoudi was defensively fortified as Fort La Tour and Aukpaque became known as Sainte-Anne des Pays-Bas when Acadian colonists settled the lower river valley . The First Nations regarded the fur traders more favorably than later settlers who started taking their land and preventing its historic use for subsistence. Colonization pressure was less severe along the Saint John River where the cold water eddy of the Gulf of Maine kept the growing season shorter than Massachusetts and the Nova Scotia peninsula nearer the warm Gulf Stream.[4] The earliest Acadians were descendants of the French sailors and shipwrights whose focus on fishing, trading, and boat repair rather than agriculture minimized land use conflicts.[5] These Acadians maintained favorable relationships with the First Nations while King Philip's War encouraged the Wolastoqiyik to join the Wabanaki Confederacy in military action against New England. The Wolastoqiyik became steadfast allies of the Acadians through the subsequent French and Indian Wars; and their Saint John River valley became the last holdout of Acadian refusal to declare allegiance to the British monarchy.[6] About a thousand Wolastoqiyik[7] sheltered a hundred Acadian families retreating up the Saint John to avoid the Acadian Expulsion as the St. John River Campaign killed livestock and burned Acadian settlements as far upstream as Sainte-Anne des Pays-Bas.[8]

International boundary dispute

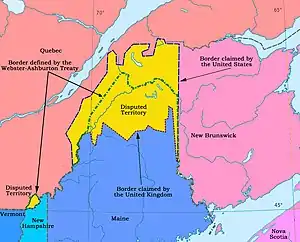

Many Loyalist refugees from the American Revolutionary War resettled in Saint John at the mouth of the river and in Sainte-Anne des Pays-Bas which was renamed Fredericton.[6] The Saint Croix River formed the Atlantic coastal boundary at the close of the war keeping the Saint John River in Canada while the Penobscot River was allocated to Massachusetts. The Treaty of Paris (1783) defined the eastern boundary of Massachusetts as a line drawn due north from the source of St. Croix River to the drainage divide of the Saint Lawrence River.[9] Persistent hostilities with the Wolastoqiyik had prevented the English treaty signatories from mapping the river headwaters. Aside from ambiguity as to which tributary might be considered the source of the Saint Croix River, the Saint John River does not flow directly south as might have been assumed from knowledge of the better mapped Hudson and Connecticut Rivers. Of greater concern to Canada, however, was discovery of how close the drainage divide was to the south bank of the Saint Lawrence, leaving Canada with a narrow band of unfavorable terrain for construction of a road to connect Atlantic Canada to Quebec through the winter months when ice closed the Saint Lawrence. Canada chose to interpret the treaty's intention as keeping the entire Saint John drainage basin under Canadian control. Surviving Acadian and Wolastoqiyik refugees continued to resist British rule while moving upriver to the Acadian Landing Site west of the Saint Croix treaty boundary where they were joined by other Acadian refugees who had fled to Quebec.[10]

After the state of Maine obtained independence from Massachusetts in 1820, Maine lumbermen encouraged these refugees to form the independent Republic of Madawaska,[11] and began diverting the Saint John headwaters into the Penobscot River so log driving could float timber harvested in the upper Saint John watershed to Bangor sawmills.[12] These provocations encouraged clarification of the disputed boundary by the Webster–Ashburton Treaty of 1842 which allocated the north bank of the Saint John west of the Saint Croix to Canada in exchange for some territory further west.[13]

Contemporary era

Today's Trans-Canada Highway follows the route of the proposed English road along the north bank of the river through the disputed portion of the drainage. Most of the Saint John drainage on the disputed south bank became Aroostook County, Maine, where the town of Madawaska still shares the Acadian French dialect with Edmundston across the river.[14] The Allagash River and Baker Branch of the Saint John River upstream of Madawaska flow through the sparsely populated North Maine Woods. These black spruce forests were a primary source of pulpwood for Maine paper mills through the 20th century. Distance from Maine cities encouraged landowners to employ Quebec lumberjacks. Édouard Lacroix developed innovative transportation methods for the river headwaters[15] including a road from Lac-Frontière, Quebec to build the isolated Eagle Lake and West Branch Railroad in 1927 and the Nine Mile Bridge over the river in 1931.[16]

Increasing recreational use of the upper river encouraged designation of the Allagash Wilderness Waterway and recognition that the river supports plant communities seldom seen elsewhere. Spring snowmelt causes scouring ice jams along the upper river leaving bedrock covered by thin, patchy acidic soil supporting one of the highest concentrations of rare plants in Maine including Clinton's bulrush, Dry Land Sedge, Mistassini primrose, Nantucket shadbush, Northern Painted Cup, and Swamp Birch.[17]

Sources

- Snow, Dean R.; Trigger, Bruce G. (1978). Handbook of North American Indians. 15. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution. p. 137.

- Erickson, Vincent O.; Trigger, Bruce G. (1978). Handbook of North American Indians. 15. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution. pp. 123–128.

- Brasser, T.J.; Trigger, Bruce G. (1978). Handbook of North American Indians. 15. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution. pp. 78–81.

- Trigger, Bruce G. (1978). Handbook of North American Indians. 15. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution. p. 2.

- Brassieur, C. Ray. "Acadian Culture in Maine" (PDF). National Park Service. United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- Michaud, Scott. "History of the Madawaska Acadians". The Michaud Barn. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- Patterson, Stephen E. (1994). The Atlantic Region to Confederation: A History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 126. ISBN 978-1-4875-1676-5.

- Grenier, John (2008). The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 199–200. ISBN 0806138769.

- Bottomly, Ron. "The Acadians in the Madawaska Region". Acadian-Home.org. Lucie LeBlanc Consentino. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- Violette, L.A. "First Madawaska Acadian Settlement". Madawaska Acadian Settlement. Acadian.org. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- Paradis, Roger (1972). "John Baker and the Republic of Madawaska" (PDF). The Dalhousie Review. 52 (1): 78–95. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- "Telos Dam and Cut (Canal)". Maine Bureau of Parks and Lands. State of Maine. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- Ridler, Jason. "Webster-Ashburton Treaty". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 27 December 2018.

- Filliez, Xavier. "French Dialects Fight for Survival in the United States". France-Amérique. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- "Edouard Lacroix". The Canadian Business Hall of Fame. JA Canada. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- "Nine-Mile". The Maine Way. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- "St. John River - Burntland Brook to Nine Mile Bridge" (PDF). Focus Areas of Statewide Ecological Significance. State of Maine. Retrieved 2 January 2019.