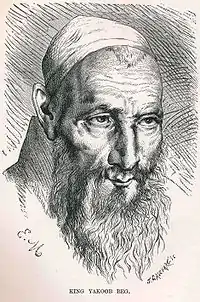

Yaqub Beg

Muhammad Yaqub Bek (محمد یعقوب بیگ; Uzbek: Яъқуб-бек, Ya’qub-bek; Chinese: 阿古柏; 1820 – 30 May 1877) was an adventurer of Uzbek descent who was the ruler of Yettishar (Kashgaria) from 1865 to 1877.[1] He held the title of Atalik Ghazi ("Champion Father").[2][3]

Yaqub Beg | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1820 |

| Died | May 30, 1877 |

| Occupation | Amir of Yettishar |

Spelling variants

In English-language literature, the name of Yaqub Beg has also been spelt as Yakub Beg (Encyclopædia Britannica), Yakoob Beg (Boulger, 1878) or Ya`qūb Beg (Kim Hodong, 2004). Authors using Russian sources have also used the spelling Yakub-bek (Paine, 1996).[4] A few publications in English written by Chinese authors spell his name Agubo, which is the Pinyin transcription of the Chinese transcription of his name, 阿古柏 (Chinese: 阿古柏帕夏; pinyin: Āgǔbó pàxià).

The first name, Muhammad, is subject to the usual variations in spelling as well.

- Ya`qūb (Arabic name, analogue of "Jacob").

- Beg, is a Turkic noble title.

Early life

Yakub Beg was born in the town of Pskente, in the Khanate of Kokand (now in Uzbekistan).[5] He rose rapidly through the ranks in the service of the Khanate of Kokand. By the year 1847 he was commander of the fort at Ak-Mechet until its capture by the Russians in 1853. He seems to have left the fort before its fall. Later that year he led an unsuccessful attempt to re-take it. He was involved in the complex factional shifts of the Khanate of Kokand. In 1864 he helped defend Tashkent during the first Russian attack.

Rule over Yettishar

Establishment of Yettishar (1865)

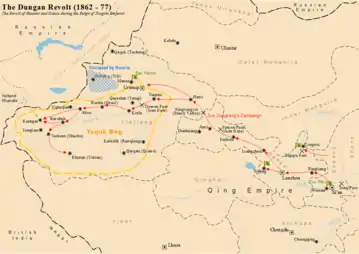

As a result of the Dungan Revolt (1862–77), by 1864 the Chinese held only the citadels of Kashgar and a few other places. The Kyrgyz or Kazakh Sadic Beg entered Kashgar, was unable to take the citadel and sent to Tashkent for a Khoja to become ruler. Burzug Khan, the only surviving son of Jahangir Khoja, left Tashkent with 6 men, was joined by Yakub Beg, left Kokand with 68 men, crossed the frontier in January 1865, gained more supporters was soon installed on the throne of his ancestors. Sadic Beg revolted, was defeated by Yakub Beg and driven beyond the mountains. Yakub went southeast to Yarkand, the largest town in the region, and was driven out by an army from Kucha. He next besieged the Chinese at Yangi Hissar for 40 days and massacred the garrison. Sadic Beg reappeared, was defeated and talked into becoming an ally. Invaders from Badakshan were also talked into alliance. A Dungan force from Kucha and eastward arrived at Maralbeshi, was defeated and 1000 of the Dungans joined Yakub Beg. Yarkand now decided to submit to Burzug Khan and his great vizier. The Chinese in the Kashgar citadel now had no hope. In September 1865 the second in command and 3000 men surrendered, converted to Islam and joined Yakub Beg. The actual commander refused and blew himself up along with his family. (The commanders of Yarkand and Kulja had done the same.) An army of rebels from Kokand arrived and joined Yakub. Late in the year Burzug Khan and Yakub went to Yarkand to deal with a disturbance. The Dungan faction suborned Yakub's Dungans and he was reduced to a few hundred men. Burzug drew off to a separate camp, Yakub defeated the Dungans, Burzug Khan fled to Kashgar and declared Yakub a traitor. The religious leaders supported Yakub and Burzug was seized in his palace. He was confined for 18 months, was exiled to Tibet and later found his way to Kokand. In a little more than a year Yakub had become master of Kashgar, Yarkand and Maralbashi, roughly the western end of the Tarim Basin as far as the Yarkand River.

The Tarim Basin was conquered by him acting as a Khoqandi foreigner and not as a local separatist Uyghur.[6]

Expansion eastward (1866–67)

Around 1866 he moved southeast from Yarkand and took Khoten by treachery and some slaughter. Beyond Khoten the south side of the Tarim Basin does not seem to have been militarily significant. In the spring or summer of 1867 he moved northeast and took Aksu easily and Kucha with some difficulty. Returning to Kashgar he took Uqturfan. Before leaving Kucha he received the submission of Karashar, Turfan, Hami and Ürümqi. Thus by his third year (1867) he had nominal control of the whole Tarim Basin and some power to the northeast at Ürümqi. To the west, at about this time, Russia annexed Tashkent and Samarkand.

Later reign

Yakub came to power after the Chinese were driven out. The Chinese only became important when they returned with an army. The Khan of Kokand had some claim over Barzug Khan as a subject, but did nothing in practice. Russia and England never recognized Yakub as a legal ruler. Yaqub entered into relations and signed treaties with the Russian Empire and Great Britain, but when he tried to get their support against China, he failed.[7]

Yaqub Beg was given the title of "Athalik Ghazi, Champion Father of the Faithful" by the Amir of Bokhara in 1866. The Ottoman Sultan gave him the title of Amir.[8]

In 1867 Yakub rejected a Russian proposal to build a road into his territory. Reinthal went to Kashgar with no effect. Yakub sent a man to Punjab and in response, in 1868, Robert Barkley Shaw went unofficially to Kashgar, the first Englishman to do so. He was soon joined by George W. Hayward. In 1870 Thomas Douglas Forsyth was sent to Kashgar as envoy, found Yakub campaigning in the east and returned to India. In 1871 Russia occupied Kulja. In 1872 Alexander Kaulbars went from Kulja to Kashgar and signed a trade treaty, but Yakub Beg was careful that Russian merchants made little profit. Kaulbars left with Haji Torah or Seyyid Yakub Khan, the nephew of Yakub Beg. Haji Torah went to Tashkent, St Petersburg and Constantinople, through the Suez Canal to India and returned with Forsyth. In 1874 Forsyth went to Kashgar and signed a trade treaty. In 1875 Russia planned to invade Kashgar, but this was interrupted by the events leading to the annexation of Kokand.

In 1869, Yakub annexed “Sirikul” (possibly Tashkorgan) on the road to India. At this point, documentation becomes poor. In 1869, he began a series of wars eastward taking Korla and other places. Turfan was taken in July 1870. There was a Battle of Ürümqi (1870). He fought with Hami and Ürümqi but did not annex them.

Popularity

Yaqub Beg's rule was unpopular among the natives with one of the local Kashgaris, a warrior and a chieftain's son, commenting: "During the Chinese rule there was everything; there is nothing now." There was also a falling-off in trade.[9] Yakub Beg was disliked by his Turkic Muslim subjects, burdening them with heavy taxes and subjecting them to a harsh version of Islamic Sharia law.[10][11]

Korean historian Kim Hodong points out the fact that his disastrous and inexact commands failed the locals and they in turn welcomed the return of Chinese troops.[12] Qing dynasty general Zuo Zongtang wrote that "The Andijanis are tyrannical to their people; government troops should comfort them with benevolence. The Andijanis are greedy in extorting from the people; government troops should rectify this by being generous."[13]

Downfall (1877)

The Chinese began their reconquest in 1876. Yakub died in 1877 while retreating from the Chinese.

Death

His manner of death is unclear. The Times of London and the Russian Turkestan Gazette both reported that he had died after a short illness.[14] The contemporaneous historian Musa Sayrami (1836–1917) states that he was poisoned on May 30, 1877 in Korla by the former hakim (local city ruler) of Yarkand, Niyaz Hakim Beg, after the latter concluded a conspiracy agreement with the Qing (Chinese) forces in Jungaria.[14] However, Niyaz Beg himself, in a letter to the Qing authorities, denied his involvement in the death of Yakub Beg, and claimed that the Kashgarian ruler committed suicide.[14] Some say that he was killed in battle with the Chinese.[15]

While contemporaneous Muslim writers usually explained Yakub Beg's death by poisoning, and the suicide theory was apparently the accepted truth among the Qing generals of the time, modern historians, according to Kim Hodong, think that natural death (of a stroke) is the most plausible explanation.[14][16] Contemporaneous western sources say the Chinese got rid of him by poisoning him or some other sort of subversive act.[17] Westerners also say he was assassinated.[18]

The exact date of Yakub Beg's death is also somewhat uncertain. Although Sayrami claimed that he died on April 28, 1877, modern historians think that this is impossible, as Przewalski met him on May 9. The Chinese sources usually give May 22 as the date of his death, while Aleksey Kuropatkin thought it to be May 29. Late May, 1877 is therefore thought to be the most likely time period.[14]

Yaqub Beg and his son Ishana Beg's corpses were "burned to cinders" in public. This angered the population in Kashgar, but Chinese troops quashed a rebellious plot by Hakim Khan to rebel.[19] Four of his sons and two grandsons were captured by the Chinese; one son was beheaded, one grandson died, and the rest were sentenced to be castrated and enslaved to soldiers.[20] Surviving members of Yaqub Beg's family included his 4 sons, 4 grandchildren (2 grandsons and 2 granddaughters) and 4 wives. They either died in prison in Lanzhou, Gansu, or were killed by the Chinese. His sons Yima Kuli, K'ati Kuli, Maiti Kuli, and grandson Aisan Ahung were the only survivors in 1879. They were all underage children, and put on trial, sentenced to an agonizing death if they were complicit in their father's rebellious "sedition", or if they were innocent of their father's crimes, were to be sentenced to castration and serving as a eunuch slave to Chinese troops, when they reached 11 years old.[21][22] Although some sources assert that the sentence of castration was carried out, official sources from the US State Department and activists involved in the incident state that Yaqub Beg's sons and grandson had their sentence commuted to life imprisonment with a fund provided for their support.[23][24][25]

Legacy

After his death his state of Kashgaria rapidly fell apart, and Kashgar was reconquered by the Qing dynasty and later inherited by the Republic of China.

Rebiya Kadeer claimed Yakub Beg was a "Uyghur hero".[26]

Tributes

One source says that his tomb was at Kashgar but was razed by the Chinese in 1878.[27][28]

The name Yaqub Beg was used for a son of Yulbars Khan.[29]

In media

Poems were written about the victories of Yaqub Beg's forces over the Chinese and the Dungans (Chinese Muslims).[30]

Yaqub Beg makes a notable appearance in the second half of George Macdonald Fraser's novel Flashman at the Charge.

References

Notes

- Olivieri, Chiara (2018). "Religious Independence of Chinese Muslim East Turkestan "Uyghur"". In Dingley, James; Mollica, Marcello (eds.). Understanding Religious Violence: Radicalism and Terrorism in Religion Explored Via Six Case Studies. ISBN 9783030002848.

- "Atalik". Encyclopaedia of Islam: Supplement. 12. 1980. p. 98. ISBN 9004061673. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- "Yakub Beg". Encyclopædia Britannica. 15 September 2019. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- "Imperial Rivals: China, Russia, and Their Disputed Frontier", by Sarah C. M. Paine (1996) ISBN 1-56324-723-2

- "Yakub Beg: Tajik adventurer". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- James A. Millward (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. pp. 117–. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3.

- Herbert Allen Giles (1898). A Chinese biographical dictionary, Volume 2. London: B. Quaritch. p. 894. Retrieved 2011-07-13.(STANFORD UNIVERSITY LIBRARY)

- Boulger, page 118 and 220

- Demetrius Charles de Kavanagh Boulger (1878). The life of Yakoob Beg: Athalik ghazi, and Badaulet; Ameer of Kashgar. LONDON : W. H. ALLEN & CO., 13, WATERLOO PLACE, S.W.: W. H. Allen. p. 152. Retrieved 2012-01-18.

. As one of them expressed it, in pathetic language, "During the Chinese rule there was everything; there is nothing now." The speaker of that sentence was no merchant, who might have been expected to be depressed by the falling-off in trade, but a warrior and a chieftain's son and heir. If to him the military system of Yakoob Beg seemed unsatisfactory and irksome, what must it have appeared to those more peaceful subjects to whom merchandise and barter were as the breath of their nostrils?

CS1 maint: location (link) - Wolfram Eberhard (1966). A history of China. Plain Label Books. p. 449. ISBN 1-60303-420-X. Retrieved 2010-11-30.

- Linda Benson; Ingvar Svanberg (1998). China's last Nomads: the history and culture of China's Kazaks. M.E. Sharpe. p. 19. ISBN 1-56324-782-8. Retrieved 2010-11-30.

- Kim, Hodong (2004). Holy War in China: The Muslim Rebellion and State in Chinese Central Asia, 1864–1877. Stanford University Press. p. 172. ISBN 9780804767231.

- John King Fairbank (1978). The Cambridge History of China: Late Chʻing, 1800–1911, pt. 2. Cambridge University Press. pp. 221–. ISBN 978-0-521-22029-3.

- Kim (2004), pp. 167–169

- "Central and North Asia, 1800–1900 A.D." metmuseum.org. 2006. Retrieved December 14, 2006.

- The stroke (Russian: удар) version e.g. here: N. Veselovsky (Н. Веселовский), Badaulet Yaqun Beg, Ataliq of Kashgar (Бадаулет Якуб-бек, Аталык Кашгарский), in «Записки Восточного отделения Русского археологического общества», No. 11 (1899).

- George Curzon Curzon (2010). Problems of the Far East – Japan-Korea-China. READ BOOKS. p. 328. ISBN 978-1-4460-2557-4. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- John Stuart Thomson (1913). China revolutionized. INDIANAPOLIS: The Bobbs-Merrill company. p. 310. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

American Commissioner Cushing, Daniel Webster's son Fletcher, etc., arrive at Canton 1844 Manchu yellow instead of Chinese blue adopted as official color 1855 Famous Empress Dowager Tse Hsi and Viceroy Li Hung Chang arise to power 1856 Non-fulfilment of Nanking treaty with Britain causes war again 1856 Coolie slave trade for Peru, Cuba, California, etc., opens at Macao 1860 Britain and France war with China 1860 Taiping rebellion, beginning at Canton, sweeps to Nanking; opposed by the American, Ward; Chinese Gordon, etc., on behalf of Manchus.... 1863 Yung Wing brings first Chinese students to America (Hartford) 1872 Terrific Mohammedan rebellion in Shensi, Kansu, Yunnan provinces and Turkestan, suppressed by ferocious General Tso Tsung-tang, Mohammedan leader, Yakub Beg, being assassinated in Turkestan May, 1877 Sir Robert Hart establishes Chinese national customs, first guarantee for foreign loans 1886 China-Japan war over Korea; Formosa lost; indemnity also paid 1894 Emperor Kwang Hsu's reform edicts, influenced by Kang Yu Wei 1898 Siege of Peking by allies 1900 Russia-Japan war over Manchuria 1904 America, Britain and China at Shanghai agree to end opium curse I909 Death of Emperor Kwang Hsu and Empress Dowager Tse Hsi together 1909

- Appletons' annual cyclopaedia and register of important events, Volume 4. NEW YORK: TD. Appleton and company. 1880. p. 145. Retrieved 2011-05-12.

In May, Hakim Khan Tufi, the pretender to the Kashgar throne, quitted his exile on Russian territory, and, entering Kashgar with a large number of followers through the Pamir, endeavored to raise a rebellion against the Chinese. This step was taken by Hakim Khan in order to profit by the angry excitement then reigning among the Mussulmans of Kashgar on account of the burning of the remains of Yakoob Beg, their late ruler, by order of the Chinese. In consequence of the rebellious attitude of the Mussulmans of Kashgar, and their openly expressed regrets at the loss of their beloved Yakoob Beg, the Chinese authorities ordered the bodies of Yakoob Beg and of his son, Ishana Beg, to be disinterred and publicly burned to cinders. The ashes of Yakoob were, moreover', sent to Peking. Such a proceeding only served to give new force to the existing discontent, and a conspiracy among the Mohammedans was the result. Hakim Khan endeavored to take advantage of this conspiracy, but the Chinese troops put a speedy end to the troubles.

- Herbert Allen Giles (1898). A Chinese biographical dictionary, Volume 2. London: B. Quaritch. p. 894. Retrieved 2011-07-13.(STANFORD UNIVERSITY LIBRARY)

- Translations of the Peking Gazette. SHANGHAI. 1880. p. 83. Retrieved 2011-05-12.(Original from the University of California)REPRINTED FROM THE "NORTH-CHINA HERALD AND SUPREME COURT AND CONSULAR GAZETTE."

- Appletons' annual cyclopaedia and register of important events, Volume 4. NEW YORK: D. Appleton and Company. 1888. p. 145. Retrieved 2011-05-12.

At the time that Eastern Turkistan again passed into the hands of China, there were taken prisoners four sons, two grandsons, two granddaughters, and four wives of Yakoob Beg. Some of these were executed and others died; but in 1870 there remained in prison at Lanchanfoo, the capital of Kan-suh, Maiti Kuli, aged fourteen ; Yima Kuli, aged ten ; K'ati Kuli, aged six, sons of Yakoob Beg; and Aisan Ahung, aged five, his grandson. These wretched little boys were treated like state criminals. They arrived in Kan-suh in February, 1879, and were sent on to the provincial capital to be tried and sentenced by the Judicial Commissioner there for the awful crime of being sons of their father. In the course of time the Commissioner made a report of the trial, which he concluded as follows : In cases of sedition, where the law condemns the malefactors to death by the slow and painful process, the children and grandchildren, if it be shown that they were not privy to the treasonable designs of their parents, shall be delivered, no matter whether they have attained full age or not, into the hands of the imperial household to be made eunuchs of, and shall be forwarded to Turkistan and given over as slaves to the soldiery. If under the age of ten, they shall be confined in prison until they shall have reached the age of eleven, whereupon they shall be handed to the imperial household to be dealt with according to law. In the present case, Yakoob Beg's sons Maiti Kuli, Yima Kuli, and K'ati Kuli, and the rebel chief Beg Kuli's son, Aisan Ahung, are all under age, and were not, it has been proved, privy to the treasonable designs of their parents. They have, therefore, to be handed to the imperial household to be dealt with in accordance with the law, which prescribes that, in cases of sedition, the Sons and grandsons of malefactors condemned to dealt by the slow and painful process, if it be shown that they were not privy to the treasonable designs of their parents, shall, whether they have attained full age or not, be delivered into the hands of the imperial household to be made eunuchs of, and shall be sent to Turkistan to be given as slaves to the soldiery. But, as these are rebels from Turkistan, it is requested that they may, instead, be sent to the Amoor region, to be given as slaves to the soldiery there. As Maiti Kuli is fourteen, it is requested that he may be delivered over to the imperial household as soon as the reply of the Board is received. Yima Kuli is just ten, K'ati Kuli and Aisan Ahung are under ten: they have, therefore, to be confined In prison until they attain the age of eleven, when they will be delivered over to the imperial household to "be dealt with according to law.

- James D. Hague (1904). Clarence King Memoirs: The Helmet of Mambrino. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. p. 50. Retrieved 2016-09-19.

Cruelty to Children Yakoob Beg.

- "THE PROTECTION OF CHILDREN.; CASE OF THE KINGMA CHILDREN--LETTER FROM THE STATE DEPARTMENT". The New York Times. New York. 1880-03-20. Retrieved 2016-09-19.

- Jung Chang (2014). Empress Dowager Cixi: The Concubine Who Launched Modern China. New York: Anchor. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-385-35037-2. Retrieved 2016-11-03.

- Rebiya Kadeer; Alexandra Cavelius (2009). Dragon Fighter: One Woman's Epic Struggle for Peace with China. Kales Press. pp. 6–. ISBN 978-0-9798456-1-1.

- Thwaites, Richard (1986). "Real Life China 1978–1983". Rich Communications, Canberra, Australia. 0-00-217547-9. Retrieved December 14, 2006.

- Michael Dillon (1 August 2014). Xinjiang and the Expansion of Chinese Communist Power: Kashgar in the Early Twentieth Century. Routledge. pp. 11–. ISBN 978-1-317-64721-8.

- Andrew D. W. Forbes (9 October 1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: A Political History of Republican Sinkiang 1911-1949. CUP Archive. pp. 225–. ISBN 978-0-521-25514-1.

- Ildikó Bellér-Hann (2008). Community matters in Xinjiang, 1880–1949: towards a historical anthropology of the Uyghur. BRILL. p. 74. ISBN 978-90-04-16675-2. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

Sources

- Boulger, Demetrius Charles (1878). The Life of Yakoob Beg, Athalik Ghazi and Badaulet, Ameer of Kashgar. London: W. H. Allen. (Full text is available on Internet Archive; a recent reprint is available as e.g. ISBN 0-7661-8845-0)

- Kim Hodong (2004). Holy War in China: The Muslim Rebellion and State in Chinese Central Asia, 1864–1877. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4884-5.

- Yakub Beg in Encyclopædia Britannica

- Yakub Beg Invasion (At Kashgar City official website – quite detailed, although, admittedly, not in very grammatical English)

In literature

- Yakub Beg is a secondary character in the novel Flashman at the Charge, published in 1973.

- Demetrius Charles Boulger, The life of Yakoob Beg; Athalik Ghazi, and Badaulet; Ameer of Kashgar, London: Wm.H. Allen & Co., 1878 (From the Open Library)

- A fictionalization of Yakub Beg's life appears in the novel Tales of Inner Asia by Todd Gibson

External links

- Works by or about Yaqub Beg at Internet Archive

- Copper coins of the Rebels- Rashiddin and Yakub Beg

- Verin Noravank Gospels, dating from 1487, includes a rare mention of Yakub Beg