Pamir Mountains

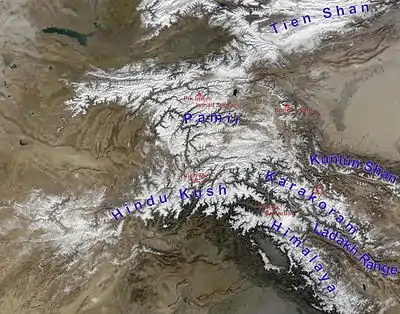

The Pamir Mountains are a mountain range between Central Asia, South Asia, and East Asia, at the junction of the Himalayas with the Tian Shan, Karakoram, Kunlun,and Hindu Kush. They are among the world's highest mountains.

| Pamir Mountains | |

|---|---|

Pamir Mountains from an airplane, June 2008 | |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Kongur Tagh |

| Elevation | 7,649 m (25,095 ft) |

| Coordinates | 38°35′39″N 75°18′48″E |

| Geography | |

| |

| Countries | Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Afghanistan and China |

| States/Provinces | Gorno-Badakhshan, Osh Region, Wakhan, Xinjiang and Gojal |

| Range coordinates | 38.5°N 73.5°E |

The Pamir Mountains lie mostly in the Gorno-Badakhshan Province of Tajikistan.[1] To the north, they join the Tian Shan mountains along the Alay Valley of Kyrgyzstan. To the south, they border the Hindu Kush mountains along Afghanistan's Wakhan Corridor. To the east, they extend to the range that includes China's Kongur Tagh, in the "Eastern Pamirs",[2] separated by the Yarkand valley from the Kunlun Mountains.

Name and etymology

Since Victorian times, they have been known as the "Roof of the World", presumably a translation from Persian.[3][4]

Names

In other languages they are called: Pashto: پامیر غرونه Pamir Ghroona; Kyrgyz: Памир тоолору, Pamir Tooloru, پامىر توولورۇ; Persian: رشته کوههای پامیر, romanized: Rešte Kuhhâ-ye Pâmir; Tajik: Ришта Кӯҳҳои Помир, romanized: Rishta Köhhoyi Pomir; Uighur: پامىر ئېگىزلىكى, Pamir Ëgizliki, Памир Езгизлики; Sanskrit: सुमेरु, Sumēru; Urdu: پامیر کوهستان, Pamir Kuhestan; simplified Chinese: 葱岭; traditional Chinese: 蔥嶺; pinyin: Cōnglǐng; Wade–Giles: Ts'ung-ling or "Onion Range" (after the wild onions growing in the region);[5][6] Dungan: Памир or Цунлин, written in Xiao'erjing: پَامِعَر or ڞوْلٍْ. The name "Pamir" is used more commonly in Modern Chinese and loaned as simplified Chinese: 帕米尔; traditional Chinese: 帕米爾; pinyin: Pàmǐ'ěr.

"A pamir"

According to Middleton and Thomas, "pamir" is a geological term.[7] A pamir is a flat plateau or U-shaped valley surrounded by mountains. It forms when a glacier or ice field melts leaving a rocky plain. A pamir lasts until erosion forms soil and cuts down normal valleys. This type of terrain is found in the east and north of the Wakhan,[8] and the east and south of Gorno-Badakhshan, as opposed to the valleys and gorges of the west. Pamirs are used for summer pasture.[7][8]

The Great Pamir is around Lake Zorkul. The Little Pamir is east of this in the far east of Wakhan.[8] The Taghdumbash Pamir is between Tashkurgan and the Wakhan west of the Karakoram Highway. The Alichur Pamir is around Yashil Kul on the Gunt River. The Sarez Pamir is around the town of Murghab, Tajikistan. The Khargush Pamir is south of Lake Karakul. There are several others.

The Pamir River is in the south-west of the Pamirs.

Geography

Mountain

The three highest mountains in the Pamirs core are Ismoil Somoni Peak (known from 1932 to 1962 as Stalin Peak, and from 1962 to 1998 as Communism Peak), 7,495 m (24,590 ft); Ibn Sina Peak (still unofficially known as Lenin Peak), 7,134 m (23,406 ft); and Peak Korzhenevskaya (Russian: Пик Корженевской, Pik Korzhenevskoi), 7,105 m (23,310 ft).[9] In the Eastern Pamirs, China's Kongur Tagh is the highest at 7,649 m (25,095 ft).

Among the significant peaks of the Pamir Mountains are the following:[10]

Remark: The summits of the Kongur and Muztagata Group are in some sources counted as part of the Kunlun, which would make Pik Ismoil Somoni the highest summit of the Pamir.

Glaciers

There are many glaciers in the Pamir Mountains, including the 77 km (48 mi) long Fedchenko Glacier, the longest in the former USSR and the longest glacier outside the polar regions.[11] Approximately 12,500 km2 (ca. 10%)[12] of the Pamirs are glaciated. Glaciers in the Southern Pamirs are retreating rapidly. Ten percent of annual runoff is supposed to originate from retreating glaciers in the Southern Pamirs.[12] In the North-Western Pamirs, glaciers have almost stable mass balances.[12]

Climate

Covered in snow throughout the year, the Pamirs have long and bitterly cold winters, and short, cool summers. Annual precipitation is about 130 mm (5 in), which supports grasslands but few trees.

Paleoclimatology during the Ice Age

The East-Pamir, in the centre of which the massifs of Mustagh Ata (7620 m) and Kongur Tagh (Qungur Shan, 7578, 7628 or 7830 m) are situated, shows from the western margin of the Tarim Basin an east–west extension of c. 200 km. Its north–south extension from King Ata Tagh up to the northwest Kunlun foothills amounts to c.170 km. Whilst the up to 21 km long current valley glaciers are restricted to mountain massifs exceeding 5600 m in height, during the last glacial period the glacier ice covered the high plateau with its set-up highland relief, continuing west of Mustagh Ata and Kongur. From this glacier area an outlet glacier has flowed down to the north-east through the Gez valley up to c.1850 m asl (meters above sea level) and thus as far as to the margin of the Tarim basin. This outlet glacier received inflow from the Kaiayayilak glacier from the Kongur north flank. From the north-adjacent Kara Bak Tor (Chakragil, c. 6800 or 6694 m) massif, the Oytag valley glacier in the same exposition flowed also down up to c. 1850 m asl. At glacial times the glacier snowline (ELA[upper-alpha 1]) as altitude limit between glacier nourishing area and ablation zone, was about 820 to 1250 metres lower than it is today.[14][15] Under the condition of comparable proportions of precipitation there results from this a glacial depression of temperature of at least 5 to 7.5 °C.

Economy

Coal is mined in the west, though sheep herding in upper meadowlands is the primary source of income for the region.

Exploration

- This section is based on the book by R. Middleton and H. Thomas[7]

.jpg.webp)

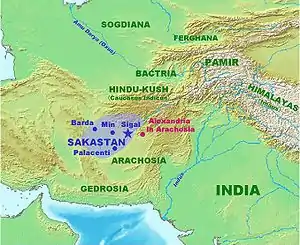

The lapis lazuli found in Egyptian tombs is thought to come from the Pamir area in Badakhshan province of Afghanistan. About 138 BC Zhang Qian reached the Fergana Valley northwest of the Pamirs. Ptolemy vaguely describes a trade route through the area. From about 600 AD, Buddhist pilgrims travelled on both sides of the Pamirs to reach India from China. In 747 a Tang army was on the Wakhan River. There are various Arab and Chinese reports. Marco Polo may have travelled along the Panj River. In 1602 Bento de Goes travelled from Kabul to Yarkand and left a meager report on the Pamirs. In 1838 Lieutenant John Wood reached the headwaters of the Pamir River. From about 1868 to 1880, a number of Indians in the British service secretly explored the Panj area. In 1873 the British and Russians agreed to an Afghan frontier along the Panj River. From 1871 to around 1893 several Russian military-scientific expeditions mapped out most of the Pamirs (Alexei Pavlovich Fedchenko, Nikolai Severtzov, Captain Putyata and others. Later came Nikolai Korzhenevskiy). Several local groups asked for Russian protection from Afghan raiders. The Russians were followed by a number of non-Russians including Ney Elias, George Littledale, the Earl of Dunmore, Wilhelm Filchner and Lord Curzon who was probably the first to reach the Wakhan source of the Oxus River. In 1891 the Russians informed Francis Younghusband that he was on their territory and later escorted a Lieutenant Davidson out of the area ('Pamir Incident'). In 1892 a battalion of Russians under Mikhail Ionov entered the area and camped near the present Murghab. In 1893 they built a proper fort there (Pamirskiy Post). In 1895 their base was moved to Khorog facing the Afghans.

In 1928 the last blank areas around the Fedchenko Glacier were mapped out by a German-Soviet expedition under Willi Rickmer Rickmers.

Discoveries

In the early 1980s, a deposit of gemstone-quality clinohumite was discovered in the Pamir Mountains. It was the only such deposit known until the discovery of gem-quality material in the Taymyr region of Siberia, in 2000.

The earliest known evidence of human cannabis use was found in tombs at the Jirzankal Cemetery.[16]

Transport

The Pamir Highway, the world's second highest international road, runs from Dushanbe in Tajikistan to Osh in Kyrgyzstan through the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Province, and is the isolated region's main supply route. The Great Silk Road crossed a number of Pamir Mountain ranges.[17]

Tourism

In December 2009, the New York Times featured articles on the possibilities for tourism in the Pamir area of Tajikistan.[18][19] 2013 proved to be the most successful year ever for tourism in the region and tourism development continues to be the fastest growing economic sector. The META (Murghab Ecotourism Association) website (www.meta.tj) provides an excellent repository of tourism related resources for the Eastern Pamir region.

Strategic position

Historically, the Pamir Mountains were considered a strategic trade route between Kashgar and Kokand on the Northern Silk Road, a prehistoric trackway, and have been subject to numerous territorial conquests. The Northern Silk Road (about 2,600 km (1,616 mi) in length) connected the ancient Chinese capital of Xi'an over the Pamir Mountains towards the west to emerge in Kashgar before linking to ancient Parthia.[20] In the 20th century, they have been the setting for Tajikistan Civil War, border disputes between China and Soviet Union, establishment of US, Russian, and Indian military bases,[21] and renewed interest in trade development and resource exploration.[22][23] China has since resolved most of those disputes with Central Asian countries.[24]

Religion

Some researchers identify the Pamirs with the Mount Meru or Sumeru.[25][26][27][28][29][30][31] The Mount Meru is the sacred five-peaked mountain of Buddhist, Jain, and Hindu cosmology and is considered to be the center of all the physical, metaphysical and spiritual universes.[32]

See also

- Pamir National Park

- Pamir languages

- List of mountain ranges

- List of highest mountains

- Soviet Central Asia

- Central Asia

- Mount Imeon

- Ak-Baital Pass

- China–Tajikistan border

- Kam Air Flight 904 – crashed into Pamir Mountains; the cause remains unknown

- Chalachigu Valley

Notes

- The snow line that separates the snow above from the firn (1 yr old snow) or bare glacier ice below is the equilibrium line altitude (ELA).[13]

References

- According to the Big Soviet Encyclopedia "The question of the natural boundaries of Pamir is debatable. Normally Pamir is regarded as covering the territory from Trans-Alay Range to the north, Sarykol Range to the east, Lake Zorkul, Pamir River, and the upper reaches of Panj River to the south, and the meridional section of the Panj valley to the west; to the north-west Pamir includes the eastern parts of Peter the Great and Darvaz ranges."

- N. O. Arnaud; M. Brunel; J. M. Cantagrel; P. Tapponnier (1993). "High cooling and denudation rates at Kongur Shan, Eastern Pamir (Xinjiang, China)". Tectonics. 12 (3): 1335–1346. doi:10.1029/93TC00767.

- Encyclopædia Britannica 11th ed. 1911 Archived 2016-04-23 at the Wayback Machine: PAMIRS, a mountainous region of central Asia...the Bam-i-dunya ("The Roof of the World"); The Columbia Encyclopedia, 1942 ed., p.1335: "Pamir (Persian = roof of the world)"; The Pamirs, a region known to the locals as Pomir – "the roof of the world".

- Social and Economic Change in the Pamirs, pp. 13–14, by Frank Bliss, Routledge, 2005, ISBN 0-415-30806-2, ISBN 978-0-415-30806-9: Pamir = a Persian compilation of pay-I-mehr, the "roof of the world".

- Li, Daoyuan. [Commentary on the Water Classic] (in Chinese). 2 – via Wikisource.

蔥嶺在敦煌西八千里,其山高大,上生蔥,故曰蔥嶺也。(quoting from the "西河舊事") The Onion Range is 8,000 Li west of Dunhuangin Uzbek Language "Pamir Tog'i". Its mountains are high and onions grow on them, therefore it is called Onion Range.

- "The origin of the Chinese name "Onion Range" for Pamir". Depts.washington.edu. 2002-04-14. Retrieved 2009-08-10.

- Robert Middleton and Huw Thomas, 'Tajikistan and the High Pamirs',Odyssey Books, 2008

- Aga Khan Development Network (2010): Wakhan and the Afghan Pamir p.3 Archived 2011-01-23 at the Wayback Machine

- Tajikistan: 15 Years of Independence, statistical yearbook, Dushanbe, 2006, p. 8, in Russian.

- Heights of mountains over 6,750 metres in accordance with: List lf all mountains of Asia with a height of over 6,750 metres. www.8000ers.com (retrieved 6 April 2010)

- In the Karakoram Mountains, Siachen Glacier is 76 km long, Biafo Glacier is 67 km long, and Baltoro is 63 km long. The Bruggen or Pio XI Glacier in southern Chile is 66 km long. Kyrgyzstan's South Inylchek (Enylchek) Glacier is 60.5 km in length. Measurements are from recent imagery, generally with Russian 1:200,000 scale topographic mapping for reference as well as the 1990 Orographic Sketch Map: Karakoram: Sheets 1 and 2, Swiss Foundation for Alpine Research, Zurich.

- Knoche, Malte; Merz, Ralf; Lindner, Martin; Weise, Stephan M. (2017-06-13). "Bridging Glaciological and Hydrological Trends in the Pamir Mountains, Central Asia". Water. 9 (6): 422. doi:10.3390/w9060422.

- "Mendenhall Glacier Facts" (PDF). University of Alaska Southeast. Juneau, Alaska, USA: University of Alaska Southeast. 29 April 2011. p. 2. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- Kuhle, M. (1997):New findings concerning the Ice Age (LGM) glacier cover of the East Pamir, of the Nanga Parbat up to the Central Himalaya and of Tibet, as well as the Age of the Tibetan Inland Ice. Tibet and High Asia (IV). Results of Investigations into High Mountain Geomorphology. Paleo-Glaciology and Climatology of the Pleistocene. GeoJournal, 42, (2–3), pp. 87–257.

- Kuhle, M. (2004):The High Glacial (Last Ice Age and LGM) glacier cover in High- and Central Asia. Accompanying text to the mapwork in hand with detailed references to the literature of the underlying empirical investigations. Ehlers, J., Gibbard, P. L. (Eds.). Extent and Chronology of Glaciations, Vol. 3 (Latin America, Asia, Africa, Australia, Antarctica). Amsterdam, Elsevier B.V., pp. 175–199.

- The origins of cannabis smoking: Chemical residue evidence from the first millennium BCE in the Pamirs

- "Official Website of Pamir Travel". Pamir Travel. Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2007-08-03.

- "The Pamir Mountains of Tajikistan". The New York Times. Retrieved 2015-01-08.

- Isaacson, Andy (17 December 2009). "Pamir Mountains, the Crossroads of History". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2014-08-11.

- "Silk Road, North China, C.Michael Hogan, the Megalithic Portal, ed. A. Burnham". Megalithic.co.uk. Retrieved 2009-08-10.

- "India's 'Pamir Knot'". The Hindu. 11 November 2003. Archived from the original on 2007-12-10. Retrieved 2007-08-03.

- "The West Is Red". Time. Retrieved 2007-08-26.

- "Huge Market Potential at China-Pakistan Border". China Daily. Retrieved 2007-08-26.

- "China's Territorial and Boundary Affairs". Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the People's Republic of China. 2003-06-30. Retrieved 2017-02-05.

- Chapman, Graham P. (2003). The Geopolitics of South Asia: From Early Empires to the Nuclear Age. p. 16.

- George Nathaniel Curzon; The Hindu World: An Encyclopedic Survey of Hinduism, 1968, p 184

- Benjamin Walker - Hinduism; Ancient Indian Tradition & Mythology: Purāṇas in Translation, 1969, p 56

- Jagdish Lal Shastri, Arnold Kunst, G. P. Bhatt, Ganesh Vasudeo Tagare - Oriental literature; Journal of the K.R. Cama Oriental Institute, 1928, p 38

- Bernice Glatzer Rosenthal - History; Geographical Concepts in Ancient India, 1967, p 50

- Bechan Dube - India; Geographical Data in the Early Purāṇas: A Critical Study, 1972, p 2

- Dr M. R. Singh - India; Studies in the Proto-history of India, 1971, p 17

- Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam (ed.). India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 78.

Further reading

- Curzon, George Nathaniel. 1896. The Pamirs and the Source of the Oxus. Royal Geographical Society, London. Reprint: Elibron Classics Series, Adamant Media Corporation. 2005. ISBN 1-4021-5983-8 (pbk; ISBN 1-4021-3090-2 (hbk).

- Gordon, T. E. 1876. The Roof of the World: Being the Narrative of a Journey over the high plateau of Tibet to the Russian Frontier and the Oxus sources on Pamir. Edinburgh. Edmonston and Douglas. Reprint by Ch’eng Wen Publishing Company. Taipei. 1971.

- Toynbee, Arnold J. 1961. Between Oxus and Jumna. London. Oxford University Press.

- Wood, John, 1872. A Journey to the Source of the River Oxus. With an essay on the Geography of the Valley of the Oxus by Colonel Henry Yule. London: John Murray.

- Horsman, S. 2002. Peaks, Politics and Purges: the First Ascent of Pik Stalin in Douglas, E. (ed.) Alpine Journal 2002 (Volume 107), The Alpine Club & Ernest Press, London, pp 199–206.

- Leitner, G. W. 1890. Dardistan in 1866, 1886 and 1893: Being an Account of the History, Religions, Customs, Legends, Fables and Songs of Gilgit, Chilas, Kandia (Gabrial) Yasin, Chitral, Hunza, Nagyr and other parts of the Hindukush. With a supplement to the second edition of The Hunza and Nagyr Handbook. And an Epitome of Part III of the author's “The Languages and Races of Dardistan”. First Reprint 1978. Manjusri Publishing House, New Delhi.

- Strong, Anna Louise. 1930. The Road to the Grey Pamir. Robert M. McBride & Co., New York.

- Slesser, Malcolm "Red Peak: A Personal Account of the British-Soviet Expedition" Coward McCann 1964

- Tilman, H. W. "Two Mountains and a River" part of "The Severn Mountain Travel Books". Diadem, London. 1983

- Waugh, Daniel C. 1999. "The ‘Mysterious and Terrible Karatash Gorges’: Notes and Documents on the Explorations by Stein and Skrine." The Geographical Journal, Vol. 165, No. 3. (Nov., 1999), pp. 306–320.

- The Pamirs. 1:500.000 – A tourist map of Gorno-Badkshan-Tajikistan and background information on the region. Verlag „Gecko-Maps“, Switzerland 2004 (ISBN 3-906593-35-5)

- Dagiev, Dagikhudo, and Carole Faucher, eds. Identity, History and Trans-nationality in Central Asia: The Mountain Communities of Pamir. Routledge, 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pamir Mountains. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Pamirs. |