187th Infantry Regiment (United States)

The 187th Infantry Regiment (Rakkasans)[1] is a regiment of the 101st Airborne Division. The nickname "Rakkasans" is derived from the Japanese word for parachute (literally "umbrella for falling", 落下傘). The name was given to the 187th during its tour in occupied Japan following World War II. When a translator dealing with local Japanese dignitaries was trying to explain what their unit was trained to do, (and not knowing the Japanese word for "airborne soldiers") he used the phrase "parachute-men" (literally "falling down umbrella men"), or rakkasan. Amused by the clumsy word, the locals began to call the troopers by that nickname; it soon stuck and became a point of pride for the unit. (Note that modern Japanese uses the English loanword パラシュート (parashūto) for parachute.)

| 187th Infantry Regiment | |

|---|---|

Coat of arms | |

| Active | 1943–present |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Size | Regiment |

| Part of | 101st Airborne Division |

| Garrison/HQ | Fort Campbell |

| Nickname(s) | Rakkasans[1] |

| Motto(s) | Ne Desit Virtus (Let Valor Not Fail) |

| Engagements |

|

| Decorations | |

| Insignia | |

| Distinctive unit insignia |  |

| Background trimming for 1st and 3rd Battalions |   |

U.S. Infantry Regiments | |

|---|---|

| Previous | Next |

| 186th Infantry Regiment | 188th Infantry Regiment |

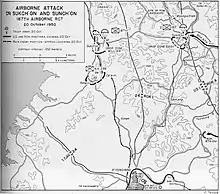

Beginning as a glider infantry regiment of the 11th Airborne Division in 1943, the 187th Infantry Regiment has fought in four wars, World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and the Persian Gulf War. The 187th entered combat on Leyte Island in the Philippines, fought in two other major campaigns in the Pacific, and was chosen to be the among the first American units sent to occupy Japan. The 187th was the only airborne unit used during the Korean War, operating as a separate airborne regimental combat team with two combat jumps. In Vietnam, the 3rd Battalion, 187th Infantry Regiment, fought as an air mobile unit, making 115 helicopter assaults. In Operation Desert Storm, the Rakkasans made the longest and largest combat air assault in military history when it air assaulted from Saudi Arabia to the Euphrates River.[2]:374

As of 2012, the 1st and 3rd battalions are the only active elements of the regiment; they are assigned to the 3rd Brigade Combat Team, 101st Airborne Division.

World War II

The 187th Infantry Regiment was originally constituted in the War Department files as the 187th Glider Infantry Regiment (GIR) on 12 November 1942 and activated with the 11th Airborne Division at Camp Mackall, North Carolina on 25 February 1943, under the command of Colonel Harry B. Hildebrand. The first recruits arrived on 2 March 1943. The 187th went through basic training from 15 March to 21 June 1943. After a period of squad-, platoon-, and company-level unit training, the 187th started formal glider training at Laurinburg-Maxton Army Airfield in late July 1943. Although it was originally a two-battalion glider-borne regiment, the men of the 187th would become dual qualified, able to enter combat either by glider or parachute.[2]:3–10

The Knollwood Maneuver

I do not believe in the airborne division. I believe that airborne troops should be reorganized into self-contained units, comprising infantry, artillery, and special services, all of about the strength of a regimental combat team [...] To employ at any time and place a whole division would require a dropping over such an extended area that I seriously doubt that a division commander could regain control and operate the scattered forces as one unit.

— Lieutenant General Dwight D. Eisenhower at the conclusion of his performance review of the American airborne forces during Operation Husky, 20 September 1943

Within the US Army hierarchy, some senior officers questioned the practicality of airborne forces as a combat entity. The Germans had successfully used airborne forces during the invasions of the Netherlands in May 1940 and Crete in May 1941. Wartime was proving tough for American airborne forces. In November 1942, as part of Operation Torch in the North African campaign, US paratroopers who missed their drop zone (DZ) marched 35 miles (56 km) to capture an airfield already in the hands of friendly forces. During the Allied invasion of Sicily in July 1943, US paratroopers once more landed far from their intended targets. But the real tragedy came when friendly fire brought down 23 aircraft and damaged 37 more; 318 paratroopers and airmen were killed or wounded. The poor performance of American airborne forces in Sicily prompted Lieutenant General Dwight D. Eisenhower to recommend to US Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall that division-size airborne units were too difficult to control in combat.

Lieutenant General Lesley J. McNair, the Army Ground Forces commanding general, took General Eisenhower's words seriously and, in the fall of 1943, convened a review board headed by Major General Joseph M. Swing, the 11th Airborne Division commanding general, to examine the doctrine, organization, and training of US Army airborne forces. The "Swing Board," as it was informally known, convened at Camp Mackall in mid-September with experienced parachute and glider unit commanders and staff officers, as well as I Troop Carrier Command veterans and glider pilots as the other board members. The Swing Board reviewed German, British, and American airborne operations, studied the airborne division organization, and analyzed the problems encountered by the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) troop carrier units during the North African and Sicilian operations. At the end of September, the review was completed with the board recommending the continuation of the airborne division and the publication of War Department (WD) Training Circular 113, Employment of Airborne and Troop Carrier Forces (dated 9 October 1943), formalizing the responsibilities and relationships between the airborne and troop carrier commands. Despite the recommendations, General McNair was still not convinced and decided to test the effectiveness of the airborne division concept before he made his decision. McNair ordered General Swing to plan an airborne operation for December in which the entire 11th Airborne Division would mount up in C-47 transports and CG-4A gliders at multiple Army airfields in North and South Carolina, take off and rendezvous in-flight over the Atlantic coast, fly a circuitous route of approximately 200 miles (320 km), a portion of which would be over open-ocean at night before turning inland toward the drop and landing zones, parachute- and glider-land after dark at precise times and locations, and reinforce, resupply, evacuate, and support itself by air for three or four days. It was obvious that the future of the airborne division depended upon a successful operation. Swing and his staff commenced planning the operation per McNair's order and WD Training Circular 113. All that remained was to write the operations order (OPORD). On 15 November, the 11th Airborne Division received its mission from Headquarters, Airborne Command at Camp Mackall. The 11th Airborne Division, reinforced by the 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR), was to assault on D-Day, 7 December, capture Knollwood Army Auxiliary Airfield (present-day Moore County Airport), establish an airhead around the airfield, and prevent "enemy" reinforcement. Defending Knollwood and selected critical points was a regimental combat team (RCT) consisting of an infantry battalion, an antitank company, a field artillery battery, and a medical detachment from the 17th Airborne Division combined with a battalion from the 541st PIR.[3]

On 4 December, the 11th Airborne Division, with the 501st PIR attached, staged its parachute and glider units at Pope Army Airfield at Fort Bragg, Mackall Army Airfield at Camp Mackall, Lumberton Army Auxiliary Airfield, and Laurinburg-Maxton Army Airfield in North Carolina, and Florence Army Airfield in South Carolina. The 187th GIR and its direct-support 674th Glider Field Artillery Battalion (GFAB) (75mm pack howitzer) loaded their equipment aboard the gliders and awaited the mount-up order. Foul weather postponed the operation for 24 hours. About midnight on 6 December, 200 C-47s towing 234 CG-4As (100 gliders were double-towed) began taking off from the airfields for the mass airborne assault. Numerous C-47s carried a full load of 18 combat-equipped paratroopers and towed either one or two gliders full of soldiers and equipment. As the C-47s gained altitude, they began forming into tight three-plane Vs, with three groups together forming a V-of-Vs formation, nine aircraft wide. The air armada flew east out over the Atlantic Ocean, turned north, and finally turned back west, heading back toward the drop and landing zones in and around Southern Pines and Pinehurst, North Carolina. The famed golf courses and open fields between 5 miles (8.0 km) and 10 miles (16 km) west and north of Knollwood Airfield were designated as drop and landing zones. The assault began at 02:30 on 7 December with the gliders cutting loose from their C-47 tugs and the parachutes of the first sticks of paratroopers blossoming out the sides of the C-47s almost simultaneously. There were few difficulties. The 11th Airborne Division assembled with speed, attacked the defenders, and seized its Knollwood objectives. The division then set up the airhead around the airfield and resupplied itself by air. In 39 hours, a total of 10,282 troops were delivered by parachute, glider, or airlanded. The tally of equipment and supplies was significant: 1,830 tons of equipment and supplies; 295 jeeps; and 48 1/4-ton trailers. Total maneuver casualties were two dead and 48 minor injuries. After three days, the division returned to Camp Mackall. Afterward, the entire operation was reviewed from start to finish at Camp Mackall by commanders and the division staff. General Swing submitted his final report on the Knollwood Maneuver to General McNair and waited for a War Department decision. On 16 December, McNair's reply message read in part: “…The successful performance of your division has convinced me that we were wrong, and I shall now recommend that we continue our present schedule of activating, training and committing airborne divisions.” The Knollwood Maneuver marked the end of the training period for the 187th GIR.[3]

Source citation: Flanagan (1997). The Rakkasans. pp. 10–12.

Camp Polk

On 2 January 1944, the 11th Airborne Division began its move by train to Camp Polk, Louisiana. By 5 February, the 187th GIR was in the field near Hawthorne, Louisiana for two weeks of testing by Army Ground Force teams to determine the regiment's readiness for deployment to a combat zone. The exercises involved approach marches, attacks on an objective, perimeter defenses, and tactical withdrawals. In late February, the 187th returned to Camp Polk for re-equipment, physical examinations, inoculations for a variety of exotic diseases, and processing for overseas deployment. In the interim, General Swing established his first jump school at DeRidder Army Air Base. The 187th and the 674th GFAB provided volunteers who were less than enthused about further glider rides and were eager to collect the extra pay for the privilege of jumping out of airplanes (fifty dollars per month for enlisted men and one hundred dollars for officers). Thus began the first transformation of the 187th and 674th from purely glider outfits to airborne units. The tests at Camp Polk represented the graduation exercises for the 11th Airborne Division; the War Department had issued an alert for the division to be ready to leave Camp Polk and by 15 April, all units were restricted to the post, with commanders readying their units for overseas deployment.[2]:12–13

New Guinea

On 20 April 1944, the 11th Airborne Division started by train to Camp Stoneman, California, where it would spend six days in final preparation for overseas movement. On 2 May, the first units marched out of Camp Stoneman to nearby Pittsburg and boarded boats for the trip to the San Francisco Port of Embarkation. The boats tied up at the Oakland Mole, near the merchant marine troopships on which the division was to sail, and the troops debarked, marched into a large wharfside shed, and mounted the gangplanks of the troopships for the next phase of their trip to war. They did not know specifically where they were headed, but since they were departing from San Francisco, they reasoned that their destination was the Pacific Theater. Only time would tell; the division staff, even if they knew, would not. After three days in hot, crowded conditions below deck, the division set sail on 6 May 1944.

After about three weeks at sea, what seemed like an eternity to the GIs jammed into the stuffy and airless triple- and quadruple-decked holds of the troopships, land was spotted. The ships sailed up the winding channel of Milne Bay, Australian Papua (modern-day Papua New Guinea), and the men got their first look at the lush, verdant jungles they would come to know and hate. After stopping to take on fresh water, the ships then moved up the east coast to Oro Bay and dropped anchor on 29 May. The troops unloaded into a fleet of DUKW “Duck” amphibious trucks that had pulled up alongside the ships. After a trip to the beach and a ride along dusty roads, the DUKWs halted at a clearing around an abandoned airstrip. The 11th Airborne Division had arrived at their new home for the next six months – the Dobodura Airfield Complex. The troops unloaded, formed up into company units, and marched with their overstuffed barracks bags in the heat and humidity to company areas that had been laid out for them. The 187th GIR's jungle phase of training and acclimation to the tropics was about to begin.

The 187th GIR spent its first month in New Guinea building its area of framed pyramidal tents, mess halls, showers and latrines, dayrooms, and chapels. One notable project was the huge, sloped thatch-roofed, 400-man division chapel built with native labor by hand and without nails, using local vegetation and lumber. Once the regiment was settled, training began again. General Swing's jump school reopened and a majority of the 187th's officers and men qualified as paratroopers. In August and September, the 11th Airborne Division operated a glider school with the USAAF 54th Troop Carrier Wing (TCW) (C-47) at Nadzab. From July to September, the division and the 54th TCW conducted combined airborne-troop carrier training for a different troop carrier squadron each week. In August and September, the 187th underwent amphibious training at Oro Bay with the 4th Engineer Special Brigade. The regiment underwent live-fire training exercises for combined-arms battalion combat teams at the abandoned airstrip at Soputa. The 674th GFAB practiced its artillery skills on the ranges at Embi Lake and Soputa. On 12 October, the 11th Airborne Division received orders for an administrative (not combat-loaded) move to Leyte in the Philippines to prepare for an operation on Luzon. A segment of the division staff flew ahead to Leyte to select and set up a campsite while the rest of the division prepared to move out. The 187th Regimental Headquarters Company and the 1st Battalion (1/187th) loaded aboard the USS Cambria (APA-36) in Oro Bay. The 2nd Battalion (2/187th) flew to Finschhafen and boarded the USS Calvert (APA-32). On 11 November, the Navy, with the 11th Airborne Division loaded on nine ships, pulled out of Oro Bay. For the unknowing men aboard the transports steaming toward Leyte, combat was just a few days away.

Source citation: Flanagan (1997). The Rakkasans. pp. 13–17.

Leyte

- See also: Cannon, M. Hamlin (1993). Leyte: The Return to the Philippines (PDF).

Leyte Landing

On 18 November 1944, the 11th Airborne Division joined the Battle of Leyte by landing unopposed on Bito Beach, off Bito Lake, Leyte. The advance party from division headquarters had flown up from New Guinea to select an area for the division encampment. Because the more desirable areas along the east coast had already been occupied, Bito Beach became the bivouac area for the division. The 187th GIR set up its first bivouac near the Filipino village of Abuyog. For its first few days on Leyte, the regiment cleared and policed the beach by moving landed supplies to rear-area dumps, built a base camp, and readied itself for its first taste of combat. It would not be long in coming. On 22 November, Lieutenant General Walter Krueger, the US Sixth Army commanding general, formally attached the 11th Airborne Division to Major General John R. Hodge's XXIV Corps, consisting of the 96th and 7th Infantry Divisions. General Hodge directed General Swing to relieve the 7th Infantry Division along the Burauen-La Paz-Bugho line and destroy all Japanese forces in that area, protect and secure all corps and air corps installations in his area of operations (AO), protect the Leyte Gulf supply bases and shipping, and coordinate operations with the 96th Infantry Division on his northern flank, running generally on an east–west line through Dagami. Swing knew that the fighting strength of his division consisted of seven small infantry battalions supported by three field artillery battalions with twenty-four 75mm pack howitzers and 12 sawed-off 105mm howitzers. But he put his division in motion piecemeal as the situation demanded. Overnight, the division went from a theater reserve role to direct combat.[2]:17–24

Combat on Leyte

By the time the 11th Airborne Division entered the fight, Major General Franklin C. Sibert's X Corps, consisting of the 1st Cavalry and 24th Infantry Divisions, was attacking southward from the Pinamopoan-Carigara area; the 96th and 7th Infantry Divisions were in scattered contact with the Japanese in the Dagami-Burauen foothills. When the 11th Airborne Division relieved the 7th Infantry Division in the Burauen area, the 7th Infantry Division moved south, crossed the mountains via the Abuyog-Baybay Road, and after reaching the west coast, attacked northward, compressing the Japanese between its forces and those of the X Corps attacking southward. The 11th Airborne Division was tasked with attacking across the center of the mountains from Burauen to Albuera on the west coast.

At 07:00 on 21 November, the 511th PIR, the first 11th Airborne Division unit committed to combat, departed Bito Beach by amphibious transport and moved to Dulag, where it loaded into motor transport for its move to Burauen. The 511th's mission was to move westward across the mountains and link up with the 7th Infantry Division on the west coast. A few days later, the 188th GIR moved north from Bito Beach to protect the 511th's southern flank as it moved westward, and clear the Japanese from the area - a sector on which little intelligence had been developed and whose maps and topographical charts were virtually useless. Initially, the 187th GIR remained at Bito Beach, with Colonel Hildebrand in command of all remaining division forces. On 24 November, General Swing moved his division command post (CP) to San Pablo, a barrio outside Burauen, and occupied the former 7th Infantry Division CP. Swing moved the 75mm pack howitzers of the 674th and 675th GFABs from Bito Beach to protect the Fifth Air Force headquarters near Burauen; the glider field artillerymen, armed mainly with folding-stock M1 carbines, became infantrymen overnight. To protect Bito Beach and to provide additional protection to the 511th's pending westward move, Colonel Hildebrand sent 1/187th to the vicinity of Balinsasayao along the Abuyog-Baybay road. From that base, 1/187th sent out patrols to the west and south. Contact patrols continually worked through the Baybay Pass to keep abreast of the 7th Infantry Division, and some of these witnessed their first banzai charge, which the 7th Infantry Division always stopped, sometimes with canister shot fired from 37mm antitank guns. Meanwhile, 2/187th patrols from Bito Beach had no contact with the Japanese. But, for the 187th, these easy days along the Baybay Pass and on the beach would soon be over. Surprisingly, the 187th would have its counterpart, the Japanese Army airborne forces, to thank for its initial entry into combat.

On 27 November, the 511th PIR started its move into the hills to the west of Burauen. To replace 2/511th, 2/187th moved from Bito Beach through Dulag into defensive positions west of Burauen; they did not stay there long. On 2 December, 2/187th was ordered into the hills to follow the 511th. Also on 2 December, 1/187th was brought up from the Balinsasayao area to replace 2/187th around Burauen. The next morning, First Lieutenant Charles Olsen, the Charlie Company (C/187th) commander, met with Lieutenant Colonel George O. Pearson, 1/187th's commanding officer, and General Swing at division headquarters in San Pablo. Swing ordered C/187th sent into the hills behind 2/187th, which had already departed. He also asked for a platoon from C/187th to be detached for a combat parachute jump into Manarawat, a deserted barrio in the central highlands, halfway between Burauen and Albuera. Manarawat was a tabletop clearing in the jungle rising about 150 feet (46 m) above a streambed, surrounded on three sides by sheer, brush-covered cliffs, and on the fourth by a more gradual slope. The clearing was about 600 feet (180 m) long and 200 feet (61 m) wide. Jungle-covered mountains rose across the streambed.

1/511th, less Charlie Company (C/511th), was currently at Manarawat, which was becoming the hub for the 11th Airborne Division's operations along the mountain trails to the west. C/511th was in trouble. A treacherous Filipino guide had led the company and the 511th PIR headquarters group into a Japanese ambush near Lubi on the north trail toward Manarawat. They were surrounded, and their ammunition and rations were running low. After rejecting a Japanese offer to surrender, Colonel Orin D. Haugen, the 511th's commanding officer, and two men managed to crawl through the Japanese encirclement in the darkness and head back to the division headquarters, arriving two days later. When General Swing became aware of the situation, he ordered 1/511th to depart Manarawat and rescue C/511th and the regimental headquarters party. Fortunately, Colonel Haugen had already sent an eight-man patrol to Manarawat to guide 1/511th back to the ambush site. After Swing explained this situation to them, Lieutenant Colonel Pearson and Lieutenant Olsen of 1/187th did not question the jump order. They did not mention that 1/187th was a glider-borne unit, nor ask where the aircraft, parachutes, and drop containers were coming from. They simply said, "Yes, sir," saluted, and left. For the 187th GIR, the Leyte campaign was heating up.

First Lieutenant Chester J. Kozlowski and his 1st Platoon from C/187th made the first unit combat jump of the 11th Airborne Division – one jumper at a time from Piper L-4 Grasshopper and Stinson L-5 Sentinel artillery light observation aircraft – into Manarawat.

Source citation: Flanagan (1997). The Rakkasans. pp. 24–30.

Battle for the Airfields

On 2 December, the remnants of the Japanese 16th Division, about 500 men out of the original strength of 8,800, had assembled in the foothills southwest of Dagami and prepared to join Japanese paratroopers in a combined assault on the Buri airstrip on 5 December. On the evening of 4 December, US Sixth Army headquarters alerted General Swing to the possibility of a Japanese airborne assault somewhere on Leyte. It was believed that the Japanese intended to recapture the airfields at Burauen.[Note 1] The only combat unit immediately available at either Bito Beach or Burauen was 1/187th, the 11th Airborne Division reserve. The men of the Japanese 16th Division were unaware that the parachute drop had been postponed for 24 hours until the night of 6 December because of forecast bad weather, and following its original orders, what was left of the division moved out of the hills in the early morning hours of 6 December. US forces at the Buri airstrip consisted of 47 men of the 287th Field Artillery Observation Battalion whose mission was to locate enemy field artillery by the flash and sound of their guns and to survey and make maps to give the enemy artillery coordinates, and 157 miscellaneous troops from various service units attached to the USAAF V Bomber Command. At 06:00, approximately 150 Japanese crossed the main Dagami-Burauen road and headed eastward toward the airstrip. At 06:30, they launched their attack – over 14 hours before the paratroopers were scheduled to land. The Japanese broke into the service units' bivouac area where most of the men were still asleep in their tents, bayoneting some of the sleeping men before they could get to their weapons. Some of the Americans, shoeless and clad only in shorts and undershirts, managed to grab weapons and hold off the Japanese until they could evacuate the area. After the 11th Airborne Division headquarters learned of the attack, it radioed XXIV Corps that the Buri airstrip was under attack. Meanwhile, the Japanese entrenched in the woods to the north of the airstrip.

General Hodge had the 1st Battalion, 382nd Infantry Regiment (1/382nd) turned over to the operational control of General Swing and moved southward down the Dagami-Burauen road; a reinforced 382nd Infantry company was already in the area north of Buri. Swing directed Lieutenant Colonel Pearson to fly a 1/187th rifle platoon from the San Pablo airstrip to the Buri airstrip in the artillery liaison aircraft, with the rest of his battalion to follow on foot. The L-4s made three round trips to ferry the 1/187th platoon to the Buri airstrip, where they were met by a "very excited" group of disorganized service and air corps troops. Pearson arrived with the rest of his battalion at the Buri airstrip around 09:00. He left a rifle squad on the airstrip for security and directed the platoon that had flown into the airstrip to sweep the area west of the main road. Soon, Pearson could hear small-arms fire from the direction in which he had sent the patrols. In about half an hour, the patrols returned and reported that 26 Japanese had been killed. Pearson was convinced that the Japanese attack on the airstrip was more than a small combat patrol and that a larger number of Japanese remained in the area. Even with his entire battalion available, Pearson could only muster 180 men to defeat the remnants of the Japanese 16th Division. He prepared to attack.

1/187th formed into a line of skirmishers, 2 yards (1.8 m) apart, and advanced to the northeast. Not five minutes after they entered the dense jungle, they flushed their quarry and a series of close-quarter gunfights erupted. Occasionally, they would break through the underbrush into the open of flooded rice paddy fields, where they would find Japanese floating face down in the water, apparently dead. Prodded with bayonets, most of them would prove plenty lively until they became "real corpses." For two hours, 1/187th continued to fight its way through the steaming jungle to the north of the Buri airstrip, attacking the Japanese in their defensive positions, often in hand-to-hand combat or at close range where hand grenades and bayonets were the weapons of choice. Finally, Lieutenant Colonel Pearson called a halt to check the status of his battalion. His company commanders reported 85 Japanese killed while suffering only two of their own wounded. This battle was 1/187th's first combat mission.

Source citation: Flanagan (1997). The Rakkasans. pp. 30–36.

Clearing the Airfields

General Swing, who never missed a good fight if he could get into it, flew from San Pablo to the Buri airstrip. Swing sent a messenger to Lieutenant Colonel Pearson to tell him to take up positions along the Dagami-Burauen road, keep it open, and to "look to his west, from which he would soon expect a lot of trouble." Pearson deployed 1/187th (less C/187th at Manarawat) along the road and established his CP on a nearby bluff near the northern edge of the airstrip. Pearson had a problem – he had moved to the Buri airstrip under the assumption that his mission would last only a few hours and required speed in getting there; he had left the battalion's heavy equipment, packs, and mess equipment at San Pablo. Thus, 1/187th's mortar platoon had no mortars. The mortar platoon commander took his men down the road to a weapons depot and borrowed two mortars and ammunition; it would turn out to be a fortuitous move. At 15:00, Pearson sent a patrol to contact the 382nd Infantry battalion to the north of Buri. An hour later, a great deal of Japanese activity was observed on a hill to the west. Pearson called for and received artillery support. Unfortunately, the artillery fire was soon lifted because it was landing on the boundary between divisions and there was a probability that the target area was occupied by troops of the 96th Infantry Division. Japanese snipers harassed 1/187th along the Buri-Burauen road all afternoon. By 18:00, 1/187th had driven most of the Japanese back from the Buri airstrip, although a few pockets of resistance remained around its edges. Soon it was dusk and all was quiet. There were no rations and no idea when they would be brought up. 1/187th settled in for the night; its false sense of security and tranquility would soon be shattered.

On the evening of 6 December, the peaceful evening erupted into bedlam when incendiary bombs from Japanese bombers began exploding all around the Bayug airstrip. At the same time at San Pablo, 11th Airborne Division staff members were sitting down to dinner when they heard the drone of aircraft overhead. They looked outside and saw a number of transport aircraft – C-47s, they thought – flying low, almost directly overhead. They also saw that each transport had a man standing in the door. What the officers were witnessing was the beginning of the Japanese airborne assault to recapture the Burauen area airfields. The Japanese transports with fighter escorts were scheduled to be over the airfields at 18:40. The fighters and medium bombers were to strafe and neutralize the defenses around the Buri, San Pablo, and Bayug airstrips. At the same time, light bombers were to hit the US antiaircraft artillery positions between San Pablo and Dulag and points west. Each transport carried 15 to 20 paratroopers. Fifty-one aircraft in all were assigned to the operation. Just before dark, on schedule, the Japanese transports with fighter and bomber escort roared over the Burauen airfields. Several incendiary bombs fell on the San Pablo airstrip, setting a gasoline dump on fire and burning a liaison aircraft. Japanese fighters raced up and down the airstrips with machine guns blazing. US antiaircraft fire knocked down 18 Japanese aircraft.

Japanese paratroopers then began to descend from the transports. Between 250 and 300 paratroopers landed on or near the San Pablo airstrip. Once on the ground, the Japanese used a system of bells, whistles, horns, and even songs for assembling their units. They talked in loud tones and allegedly called out in English, "Hello, where are your machine guns?" Most of the Japanese assembled on the north side of the airstrip. They burned three or four more L-4 liaison aircraft, a jeep, several tents, and another gasoline dump. During the night of 6–7 December, a platoon from the 127th Airborne Engineer Battalion (AEB), armed with three machine guns, succeeded in scattering a group of Japanese before digging in on the southwest corner of the airstrip. Three times during the night, the Japanese charged the engineers' position; three times the Japanese were thrown back with heavy losses. The Japanese who landed west of the airstrip were between San Pablo and Bayug. They spread out with some moving down the sides of the San Pablo airstrip and others moving off to the west toward the Bayug airstrip, where they set fire to several L-4s by tossing hand grenades into the cockpits. The Japanese then moved into the Bayug bivouac area and destroyed the camp. Seventy-five American officers and men were at the Bayug airstrip; most of them dug in and defended the south side of the airstrip until the morning of 7 December. At dawn, perhaps according to the overall Japanese OPORD, after most of the Japanese paratroopers had assembled on the San Pablo runway, they moved north and west to the northern edge of the Buri airstrip and joined elements of the Japanese 16th Division.

It became clear to General Swing when he returned to San Pablo overnight that the Japanese airborne assault and air attacks were something more than a reconnaissance-in-force or a rather elaborate suicidal demolition mission. But, his seven small infantry battalions were all committed either in the hills beyond Burauen or deployed near the Buri airstrip. Accordingly, he diverted his other troops from their primary missions to acting infantry. Lieutenant Colonel Lucas E. Hoska, the 674th GFAB's commanding officer, whose battalion was at the mouth of the Bito River, north of Abuyog, was directed to leave his pack howitzers and move his battalion as rapidly as possible to San Pablo. Swing charged the 152nd Airborne Anti-Aircraft Battalion (AAAB) to use what men it had left to defend the division CP. He directed the 127th AEB to defend the airstrip.

At daylight on 7 December, a diverse group of soldiers from the 127th AEB and other division service units prepared to attack across the San Pablo airstrip to clear the Japanese and relieve some beleaguered division troops, including some of the 127th's own. Just as they were about to launch their frontal attack, the carbine-wielding artillerymen from the 674th GFAB arrived in DUKWs, dismounted, and swung into line on the right wing of the 127th AEB's composite unit. The two battalions then prepared to move out as a provisional infantry regiment under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Douglas C. Davis, the 127th's commanding officer. Just then, General Swing arrived. The similarity between the battle at the San Pablo airstrip and most Civil War battles became apparent with the engineers on the left, the artillerymen on the right, and both battalions drawn up in a line across the southern edge of the airstrip. In the center, between the two outfits, was the General, shouting as he directed Lieutenant Colonels Davis and Hoska in the attack. They in turn bellowed at their units, and the line stepped off. The Japanese were holed up all around the airstrip. Initially, the strongest resistance was met in front of the engineers to the west. By maneuvering his companies, Davis succeeded in pushing across 300 yards (270 m) to the north of the airstrip. After advancing across the runway, the engineers ran out of ammunition. The artillerymen went forward to a coconut grove, also to the north of the airstrip. The gap between the two units was closed by a strong patrol. That evening, the composite force set up in a tight defensive perimeter in that area where it remained for the next few days in defense of the San Pablo airstrip.

Meanwhile, 60 Japanese paratroopers had jumped onto the Buri airstrip. By the middle of the morning of 7 December, the Japanese had completely occupied the undefended airstrip. On the night of 6–7 December, the USAAF service personnel had abruptly fled the airstrip, leaving behind their weapons; the Japanese made "best use" of them. Late on the night of 6 December, General Swing had sent word to Lieutenant Colonel Pearson that he wanted 1/187th to clear the Buri airstrip as soon as possible. During the morning of 7 December, 1/187th was deployed along the Buri-Burauen road, taking machine-gun fire from the Japanese west of the road. Pearson directed elements of his battalion to hold this force in place while he organized his attack on the Buri airstrip to the east. At about 09:30, 1/382nd Infantry arrived from the north. At 09:45, both battalions advanced toward the Buri airstrip. Twice, 1/187th fought its way onto the northwest corner of the airstrip; twice, it was blasted off by heavy Japanese fire. 1/382nd Infantry also advanced aggressively but faltered when one of its company commanders was hit. Pearson decided to withdraw both battalions to the north and consider another way to attack the airstrip. He made a personal reconnaissance around the west end of the airstrip and decided to move a couple rifle platoons to the west and then south to the south side of the airstrip. In this position, machine guns and mortars could bring in supporting fire. 1/187th moved out at 14:00 to the west as planned, but ran into Japanese booby traps. Pearson directed the battalion's lead elements to turn southward while the machine guns were set up close to the edge of the landing strip. In less than a minute, their crews had the machine guns firing at a group of Japanese hurrying across the airstrip. In about 15 minutes, the machine-gun crews ran out of ammunition. Two men crawled to the rear to get more ammunition and returned with orders to withdraw. 1/187th and 1/382nd Infantry regrouped at the west of the airstrip. A/187th and B/187th attacked abreast to the northeast and A/382nd Infantry attacked due east. The three rifle companies ran into heavy Japanese fire but continued their advance. By 16:00, the "dog-tired" Americans were holding the southwest corner of the airstrip with their ammunition running low.

XXIV Corps headquarters had released the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 149th Infantry Regiment (1/149th and 2/149th Infantry) to General Swing's operational control for employment against the Japanese in the Burauen area. The two infantry battalions had been alerted at 02:00 on 7 December for movement to San Pablo. 1/149th Infantry arrived at the San Pablo airstrip at 14:00 and was directed to attack and secure the Buri airstrip. A/149th and C/149th Infantry deployed abreast on a frontage of 200 yards (180 m) for each company. A heavy machine-gun section was attached to each company and a D/149th Infantry mortar platoon was to support the attack from positions on the San Pablo airstrip. Moving out at 14:30, the infantrymen covered the first 400 yards (370 m) without incident but were stopped by a rain-swollen swamp. Attempts to bypass the swamp were fruitless and they were forced to wade through the sometimes shoulder-high water. The 149th Infantry companies lost contact with each other during the crossing. A/149th Infantry arrived at the Buri airstrip and made contact with 1/187th about 16:30. C/149th Infantry, delayed by a skirmish with the Japanese, did not arrive until about 18:00. Because of the lateness of the hour and the fact that observation had shown there were "many more Japanese" on the north of the airstrip than had been estimated, it was decided to establish defensive perimeters for the night. At 20:00, the sector was reported quiet.

With the arrival of the 149th and 382nd Infantry battalions in his area, Lieutenant Colonel Pearson felt that he could now attack and secure the length of the Buri airstrip. But that was not yet to be. Late in the afternoon of 7 December, General Swing sent word to Pearson to move 1/187th from the Buri airstrip area to defend the Fifth Air Force headquarters at Burauen along the Burauen-Dulag road. It was an inviting target for the Japanese 26th Division descending out of the hills to the west of Burauen. By midnight, 1/187th was at the Fifth Air Force headquarters area. 1/187th then moved into the defensive positions previously occupied by 2/187th, about 800 yards (730 m) west of Burauen on a rise in the foothills of the mountains. From the heights, they could see the battle for control of the Buri airstrip. They were also in a position to block the Japanese from attacking eastward toward Burauen.

On 10 December, after a half-hour artillery concentration, 1/149th Infantry attacked north across the Buri airstrip. In their advance, 1/149th Infantry cleared the airstrip area of individual Japanese paratroopers and destroyed the remaining pockets of resistance. 1/149th Infantry went into a perimeter defense at 17:00. The Buri airstrip was finally clear.

At 19:30, a battalion-sized force from the Japanese 26th Division launched an attack out of the hills to the west of Burauen against the various US installations in and around Burauen. The Japanese were four days late in arriving at their line of departure for the planned combined assault on the Burauen airfields, primarily because they were trying to move eastward along the same mountain trails that the 511th PIR was using to move westward. Only a little more than a battalion of the Japanese division, which was to have assisted the Japanese 16th Division, managed to arrive in a very disorganized condition. The Japanese began firing at the Fifth Air Force administration buildings. The Fifth Air Force personnel were pushed back until they reached the hospital. First Lieutenant John G. Hurster, the 1/187th mess officer, had set up his field kitchen near the hospital from where he could carry hot meals to the troops dug in the foothills to the west. The hospital's commanding officer, concerned about the safety of his staff and patients, had earlier asked Hurster to set up a perimeter around the hospital. Hurster had complied, using his cooks, supply troops, and drivers to man the perimeter. During the Japanese attack, Hurster and his assortment of converted infantrymen held their position. On the morning of 11 December, they found 19 dead Japanese. That same morning, 1/187th patrols were sent out into the foothills and killed an additional 17 Japanese. This small battle marked the end of the attack by the remnants of the Japanese 26th Division and was the last major effort by the Japanese to regain control of the Burauen airfields.

The 11th Airborne Division and the 187th GIR had their baptism of fire. The 187th had landed on Leyte not expecting to be committed to combat. Under those circumstances, coupled with the surprise Japanese assault on thinly defended installations, the 187th, committed to combat unexpectedly and in haste, performed superbly. Further tests of their fighting skill were in the immediate offing.

Source citation: Flanagan (1997). The Rakkasans. pp. 36–49.

Clearing the Mountains

While the battle for the Burauen airstrips was underway, the 511th PIR was making its way over the mountains, looking for the long-sought Japanese main supply route (MSR), with 2/187th following up behind. The mission of the 11th Airborne Division was now to fight its way over the mountains to the west coast and link up with the US Sixth Army, which was fighting its way up the west coast, north of Albuera. 2/187th, like the 511th that was ahead of it, had the terrain to fight in its march to Anonang; there was just one trail after the battalion left the relatively flat terrain west of Burauen. Late on the afternoon of 3 December, 2/187th reached Anonang, which was nothing more than a jungle clearing with an abandoned shack. Lieutenant Colonel Wilson sent Captain George Ori's F/187th to occupy an observation post (OP) on a hill to the northwest of the Anonang perimeter. Once there, Ori discovered that the OP commanded a view of a strong Japanese position on a plateau beneath it. That night, the Japanese hit Ori's position. Ori called in mortar fire from Anonang that drove off the Japanese attack. The next day, Ori sent a platoon down from the OP to probe the Japanese position. The Japanese opened up with machine guns, wounding the platoon leader and two of his men. Ori ordered a withdrawal. F/187th had run up against a Japanese force on a hill that, sometime later, would become known as "Purple Heart Hill."

The 11th Airborne Division's G-2 (intelligence) had determined the locations of the main Japanese forces remaining within the division's AO. One force that F/187th had just found was at Anonang; the other was west of Mahonag; more Japanese were retreating westward after they failed to seize the Burauen airfields. From 4 December until 11 December, 2/187th had several encounters with the Japanese around Anonang while the 511th PIR was fighting its way westward toward Mahonag. On 11 December, Brigadier General Albert Pierson, the assistant division commanding general, arrived at Anonang. After reviewing the situation, Pierson ordered an attack on the Japanese position below Ori Hill, the hill from which Captain Ori and F/187th had been repulsed earlier. On 12 December, F/187th and G/187th launched the attack with G/187th moving up a riverbed to strike the Japanese from the north and F/187th moving to hit it from the southwest – a small pincer movement. A Battery, 457th PFAB, the unit that had parachuted into Manarawat, provided artillery support. By 13:00, F/187th had cleared Ori Hill and was working down the slope toward the main Japanese position. Presently, F/187th became impeded by friendly artillery rounds that were bursting in the trees above and behind it. The artillery's forward observers with the rifle companies could hardly find their spotting rounds through the thick jungle overhang that limited visibility to a few yards. They had reverted to adjustment by sound – which proved not entirely accurate. The attack was called off.

Late on the afternoon of 13 December, Lieutenant Colonel Pearson and 1/187th arrived at Anonang with orders to relieve 2/187th. On 14 December, 2/187th was directed by division headquarters to move west to Mahonag to protect the DZ. Mahonag was nothing more than a field on a hillside, about 300 yards (270 m) long by 200 yards (180 m) wide, studded with stumps and fallen trees, and packed with hundreds of slit trenches deep enough for a soldier to stand in. The DZ was littered with boxes, cans, and debris from spent airdropped ration packs. The air was filled with the odor of unburied, decomposing Japanese bodies and a large, prosperous swarm of flies. The real estate blossomed with green, yellow, and white cargo parachutes that the men of 2/187th set up as tents for shelter. For the next few days, 2/187th dug a perimeter, incorporating some of the foxholes left by the 511th PIR.

In the middle of December, General Swing relocated his infantry battalions. The 188th GIR moved to a location near Manarawat. Colonel Hildebrand and several members of the 187th GIR headquarters staff moved to Anonang by way of Manarawat to take over command of the central mountains from Anonang to Mahonag. On 20 December, F/188th relieved 2/187th of its security mission at Mahonag, and 2/187th was ordered to move west. On 21 December, General Swing flew into Manarawat and hiked up to Mahonag, arriving late in the afternoon. At 04:00 on 23 December, Swing, Lieutenant Colonel Wilson and 2/187th with First Lieutenant Joseph B. Giordano's 2nd Platoon, G/187th leading off, departed Mahonag for a two-hour march to make contact with the 511th PIR on Rock Hill, near Anas, and aid in the breakthrough to the west coast. The 11th Airborne Division commander wanted to personally direct the breakthrough and the 511th was pushing forward along the Japanese MSR that ran along a ridge in the direction of Ormoc. The column passed through a canyon reeking with the smell of decomposing bodies, the remnants of the Japanese 26th Division that once had planned to overrun Burauen. At about 06:00, the column reached the approach to Rock Hill. At the same time, the 511th on Rock Hill launched its attack on a Japanese-occupied ridge to clear the last known Japanese position blocking the advance. The 511th attack cracked the Japanese defenses with demolition charges, flamethrowers, bazookas, and hand grenades in the final assault to annihilate the deeply entrenched Japanese. By 08:30, the ridge, lined with Japanese dead, was firmly in the 511th's possession. Word came down for 2/187th to move forward and pass through the 511th. At noon, 2/187th with Giordano's platoon on the point passed through the 511th and took over the lead in the march to the west. After putting a three-man Japanese machine gun position out of action and clearing out several weak Japanese pockets of resistance, Giordano and his platoon reached a point high on the western slope of a mountain from where they could see their goal: the west coast of Leyte. The battalion halted and popped a purple smoke grenade, the signal for friendly forces intended to attract elements of the 77th Infantry Division that might be in the vicinity. On a ridgeline to the west, purple smoke was observed. 2/187th had made visual contact with US forces on the west coast. However, the appearance of the rugged terrain between the two US forces promised that more fighting would take place before physical contact was made.

The column pushed on, continuing to follow the Japanese MSR, and soon reached the approaches to a "dangerous looking position to the front." Giordano stopped the column, put out security, and sent out a patrol to reconnoiter the position. As the column closed up, all the command hierarchy came forward to learn the reason for the halt. The patrol soon returned and reported that the ridgeline to the front was honeycombed with caves and deeply dug-in foxholes, that it appeared to have been heavily shelled and recently abandoned, and that the area was littered with dead Japanese. Giordano led his platoon to the top of the ridge and found the position well laid out, camouflaged, and dug into almost solid rock. Battered trees and the number of Japanese dead served as mute evidence of heavy fighting. Among the dead were two American soldiers who appeared to have been killed less than 24 hours before. When he reached the west end of the ridge, Giordano could see Ormoc and the seacoast. To his front, about 200 yards (180 m) away, he saw more dug-in emplacements that were soon alive with members of the US 32nd Infantry Regiment. They were amazed to see fellow Americans coming over the same Japanese positions that had given them so much trouble earlier. "Oh, yes," said one of the 32nd's infantrymen, "we expected you. We saw the purple smoke, but we didn't think that you were coming over that hill. Last night it was solid with Japanese. We lost two of our boys on it." Thus, physical contact was made with the Ormoc Corridor, the road was opened between Burauen and Anas, and the area west of Mahonag was cleared. That night, 2/187th spread out beside the Talisayan River headwaters near Albuera.

General Swing ordered the 511th PIR to secure the route from Mahonag to the coast. By Christmas Day, the 511th had cleared the mountains and was ordered back to its base camp at Bito Beach. From its base at the head of the Talisayan River, 2/187th was ordered to secure the western end of the Japanese MSR. The Japanese pocket at Anonang had still not been wiped out. The 511th and 2/187th had both butted up against this formidable Japanese position. Early on in his mountain clearing campaign, Swing realized that the Japanese position at Anonang was substantial and that it would take a well-coordinated multi-battalion effort to knock it out. He decided not to attack it in strength while the major portion of his infantry assets were fighting across the mountains to the west, which was his major mission ordered by General Krueger at Sixth Army headquarters. Now that he had linked up with the 77th Infantry Division, he felt that he could deal with the final Japanese redoubt in his AO.

The Japanese defenses at Anonang were on two parallel ridges. On the first ridge, the Japanese had dug spider holes, each between 8 feet (2.4 m) and 10 feet (3.0 m) deep, for individual riflemen. They had also dug in machine guns with overhead cover and interlocking fields of fire on both ridges. All slope faces were studded with caves that overlooked and controlled the narrow trails. In the rear of the defensive position was a bivouac area, cached with ammunition, rations, and other supplies, large enough to accommodate a regiment. The position was a concentration point for the Japanese troops in the area and it was estimated that at least 1,000 Japaneses were dug in along the ridges and gorges. The second ridge, where the Japanese had concentrated the bulk of their defenses and their manpower, became known among the 11th Airborne troops as Purple Heart Hill.

On 18 December, First Lieutenant Charles Olsen and C/187th moved from Manarawat and rejoined 1/187th at Anonang. Lieutenant Colonel Thomas L. Mann's 2/188th had been probing the Japanese-held ridges for three days, searching for an undefended or weakly held approach into the position – there were none. In the meantime, Lieutenant Colonel Pearson had pulled 1/187th back from Anonang and circled the Japanese stronghold in a wide arc, moving to the north, above the Japanese defenses. To the west of 1/187th was the Division Reconnaissance (Recon) Platoon that had traveled along the slopes of Mount Lobi to determine how far to the north that the Japanese stronghold extended; the Recon Platoon found instead that the position extended westward. Consequently, the Recon Platoon dug in on the northwest corner of the Japanese defensive network. Colonel Robert H. Soule, the 188th GIR's commanding officer, was in overall command of the assault on Purple Heart Hill. he planned his attack for the morning of 26 December. For the assault, he had 2/188th, 1/187th, and the Recon Platoon under his command. First, he moved F/188th from Mahonag down the trail to the east to set up an ambush. He then used the rest of 2/188th, located on a hill position southwest and across a gorge from the objective, first as a ploy, and then as part of the attack. Soule directed 2/188th to move southwest, away from the Japanese hill, leading the Japanese to believe that, like the four other infantry battalions that had moved out of the area, 2/188th was also moving out. Instead, 2/188th moved into a narrow, steep-sided riverbed that hid it from view, then doubled back and climbed a rock gully onto the southern slope of Purple Heart Hill. Then 2/188th turned left and moved up on the Japanese flank. As soon as they were within range and sight, the Japanese took them under heavy fire from deep entrenchments.

The Japanese on Purple Heart Hill were so well entrenched and so numerous that Colonel Soule decided to blast them with as much artillery fire as he could muster before ordering any ground attacks. During most of the night of 26 December, artillery from A Battery, 457th PFAB (which had earlier parachuted into Manarawat), Burauen, and 2/188th's mortars pounded the Japanese. Finally, after strong artillery preparation, 2/188th stormed Purple Heart Hill on the morning of 27 December and, after intense, close-in firefights and hand-to-hand combat, struggled to the top of the hill and held it. The entire battalion closed in at dusk but had no time to dig in; they just moved into the old foxholes and revetments from which they had blasted the Japanese. Those Japanese that had not been killed in the assault scattered to the north and west. Those moving northward ran into 1/187th, which was attacking southward along the gorge and up the other ridge. The Japanese fleeing westward ran into the Recon Platoon and the F/188th ambush along the Japanese MSR. The battle for Purple Heart Hill was over after almost five weeks of containment followed by the final attack. A search of the area found 238 dead Japanese. How many were buried in the subterranean galleries was unknown. It was also discovered that the elusive Japanese MSR, which wound from Ormoc Bay, ended at Anonang. Division intelligence reasoned that, because of its extensive defenses, the fact that Purple Heart Hill was the MSR's eastern terminal, Anonang was probably the Japanese 26th Division's CP.

After the success at Purple Heart Hill and the juncture of the 511th PIR and 1/187th with the other US forces on the west coast, the main battles of the 11th Airborne Division on Leyte were finished. Most of the division withdrew to the Bito Beach base camp. The 674th and 675th GFABs, still bereft of their artillery pieces and acting as infantry, remained in the hills outside Burauen, scouting and patrolling the eastern approaches to the Leyte hills. By 15 January 1945, all division units had returned to Bito Beach. On 21 January, after a division parade and awards ceremony, reviewed by Lieutenant General Robert L. Eichelberger, commanding general of the newly formed US Eighth Army, General Eichelberger told General Swing that he was "elated" that General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in the Southwest Pacific Area, had given him the "go-ahead" to invade Luzon with the 11th Airborne Division. He also assigned Swing a top priority: get to Manila, the major prize of the Pacific War to date, ahead of his competition, General Krueger's US Sixth Army.

The Battle of Leyte was over. The Americans had established a base of operations from which USAAF bombers could strike Luzon, the heart of the Philippine archipelago. Ahead was more intense fighting for the Allies. In the tents on Bito Beach, in the mess lines, and wherever the GIs gathered, the main topic of conversation centered on the location of their next fight. They knew that the US Sixth Army had invaded northern Luzon at Lingayen Gulf on 9 January. They had heard rumors that the paratroopers of the 11th Airborne Division had been alerted for a jump ahead of the Sixth Army at Nichols Field outside Manila. But toward the end of the month, unit commanders received a supply of handbooks describing the terrain and geography of southern Luzon. Division staff studied the area from Nasugbu east to Batangas City and north to Manila. Rumor became reality when the division received orders for an operation in southern Luzon.

Source citation: Flanagan (1997). The Rakkasans. pp. 49–65.

Luzon

Mounting Up

General Krueger's US Sixth Army invaded Luzon at 09:30 on 9 January 1945 with two field corps, comprising a force of some 68,000 men. Japanese General Tomoyuki Yamashita's poorly equipped Japanese Fourteenth Area Army defenders numbered about 275,000 men. To defend the largest island in the Philippines, Yamashita withdrew most of his troops from the coastal regions and prepared for a lengthy delaying action in the island's interior. His objective was to hold Luzon as long as possible to prevent the Allies from using it as a base of operations against the Japanese homeland. He deployed his main force of about 152,000 men in several mountain strongholds in the north; he sent another 50,000 men to defend southern Luzon and the hills east of Manila; he stationed a third group of 30,000 men west of the Luzon Plain in the hills dominating the huge Clark Field complex.

Back on Bito Beach, Leyte, General Swing's 11th Airborne Division headquarters received US Eighth Army Field Order No. 17 on 22 January that alerted the division for a two-pronged operation on Luzon. The division would prepare to amphibiously land a regimental combat team in the Nasugbu area on Luzon's southwest corner, seize and defend the beachhead; an airborne RCT would prepare to move by air from Leyte and Mindoro bases, land by parachute on Tagaytay Ridge, about 20 miles (32 km) to the east of the Nasugbu landing zone, and effect a juncture with the RCT moving inland from Nasugbu. The division, reinforced after assembling on Tagaytay Ridge, would prepare for further action to the north and east as directed by the Eighth Army.[Note 2]

On 24 January, General Swing issued his Field Order No. 10 for Operation Mike VI that outlined in detail the division's operation plan (OPLAN) for executing the Eighth Army field order. The 188th Glider Infantry RCT would lead the amphibious assault on the beach at Nasugbu, followed by the 187th Glider Infantry RCT with the mission of protecting the southern flank and blocking the approaches from the Balayan Bay-Calatagan Peninsula area. The 511th Parachute Infantry RCT, with the 457th PFAB attached, would drop onto Tagaytay Ridge when Swing could assure General Eichelberger, the Eighth Army's commanding general, that the amphibious force could link up with the airborne force within 24 hours. The United States Seventh Fleet would shell the beaches for one hour before the landing and the Thirteenth and Fifteenth Air Forces would provide assault and close air support. The Eighth Army designated D-Day as 31 January. The field order also ordered an amphibious dry run for the 187th and 188th glider units that were more prepared to enter combat by landing in a field than they were in wading ashore from a Navy landing craft. On 26 January, as directed, the first three waves loaded, pushed out into Leyte Bay, and then came churning back to "assault" Bito Beach. General Swing deemed the dry run a success and ordered the division's amphibious elements to embark aboard their ships for the cruise to Nasugbu. The 187th, glider and parachute trained, was now going to emulate the Marines – storm across the beaches from the sea.

The catch to the loading out of the division's amphibious elements was what ships the Navy would send, and this was not definite until the ships arrived at approximately 20:00 on 25 January. Most of the supply ships were completely loaded within 24 hours, except for the great bulk of engineer supplies, ammunition, and gasoline. The landing craft for the troops arrived at 07:00 on 27 January, and soon thereafter, the troops went aboard. The assault convoy of over 100 ships and landing craft of all types weighed anchor and steamed out to sea from Leyte that afternoon. An additional eight landing craft carried the 511th RCT to Mindoro.

Many 11th Airborne Division units went through staff and command changes. In the 187th GIR, Lieutenant Colonel George O. Pearson, 1/187th's commanding officer, took over as the 187th's executive officer; Lieutenant Colonel Arthur H. Wilson, 2/187th's commanding officer, replaced Pearson as 1/187th's commander; and Lieutenant Colonel Norman D. Tipton returned from the 511th PIR to take over his old battalion, 2/187th.

Source citation: Flanagan (1997). The Rakkasans. pp. 65–68.

Luzon Landing

At dawn on 31 January 1945, the convoy arrived off Nasugbu, Luzon in clear skies and calm seas. On their landing craft, the men of the 187th and 188th RCTs could see the white landing beaches, the town of Nasugbu, and the green mountains of southern Luzon beyond. The Wednesday morning quietude was broken at 07:00 when USAAF A-20s and P-38s appeared overhead, dropped down on the deck, and strafed the beaches. At 07:15, the Navy began shelling and rocketing Red Beach, the designated landing area. An hour later, the shelling stopped and the beachmaster landing party headed for shore. At 08:22, Generals Eichelberger and Swing received word aboard the Navy task force command ship USCGC Spencer (WPG-36) that the landing was unopposed. At 08:25, the first wave of eight LCVP landing craft motored ashore, ran up on the beach, dropped their ramps, and the 188th RCT's glider riders turned amphibians waded ashore through surf sometimes up to their chests. The first assault troops, a reconnaissance-in-force from Lieutenant Colonel Ernest H. LaFlamme's 1/188th GIR, headed for their first objective, the town of Nasugbu 1,500 yards (1,400 m) away. Some Japanese, in caves on Nasugbu Point to the north and San Diego Point on the south flank of the beachhead, fired machine guns sporadically and dropped a few artillery rounds along the beach until LaFlamme sent off patrols to silence the opposition. General Swing and the 11th Airborne Division staff transferred to LCVPs and reached the beach just behind the 188th's second wave. By 09:45, the 188th had moved through Wawa, Nasugbu, and its airstrip. At 10:00, General Eichelberger ordered the landing of the remainder of the amphibious force. At 10:30, Lieutenant Colonel "Harry" Wilson led the 187th RCT ashore. His 1/187th GIR, part of the division's floating reserve, would attach to the 188th RCT on landing. Wilson's battalion moved up behind the beach to assemble and reorganize.

After 2/188th took Lian and the Japanese had been driven back into the hills, 1/187th was attached to the 188th RCT for the march inland and up the hill on the road to Tagaytay Ridge. The remainder of the 187th RCT followed 1/187th ashore, relieved the 188th RCT on flanking missions, and assumed responsibility for the Nasugbu beachhead. One battery of the 674th GFAB remained behind on the beach to support the 187th's defense of the port. By 13:00, all combat elements of the two glider RCTs were moving inland. General Eichelberger and his small Eighth Army command group had landed and joined General Swing near the head of the column marching up Highway 17 to link up with the 511th RCT.

Source citation: Flanagan (1997). The Rakkasans. pp. 68–76.

Attack Inland

By 31 January 1945, General MacArthur had become frustrated with the US Sixth Army's slow advance on Manila from the north. MacArthur's primary concern was the capture of Manila and the airbase at Clark Field, which were required to support future operations. "Get to Manila," he ordered his two field commanders. General Eichelberger reasoned that if he could make the Japanese think that his small force moving up Highway 17 across Tagaytay Ridge and heading for Manila from the south was a larger force, he would have a tactical advantage and a relatively unopposed run-up to the capital. He directed General Swing to move the 188th RCT forward as rapidly as possible. Colonel Soule led his 188th RCT, reinforced with 1/187th, inland at a rapid pace. By 14:30, the lead unit had reached the Palico River Bridge that spanned a gorge 85 feet (26 m) deep and 250 feet (76 m) wide. Soule had moved inland so rapidly that he caught the Japanese sappers preparing to blow the bridge by surprise. The lead elements dashed across the bridge and routed the Japanese. The 127th AEB inactivated the demolition charges and reinforced the bridge sections that the Japanese had weakened. By 15:30, the bridge and surrounding area were secured.

At 18:00, Colonel Soule and his reinforced 188th RCT were in the vicinity of Tumalim, about eight miles inland from the beachhead. Beyond Tumalim, the highway rose more sharply and the advance slowed as the 188th found itself moving cautiously through narrow passes, bordered by steep wooded banks, ideal for ambushes. The normal tactic of fighting the Japanese in the Pacific was to halt just before dark and set a perimeter defense before eating whatever rations were on hand and bedding down for the night. General Eichelberger discerned that if the 188th kept moving at night, the Japanese might be thrown off balance and would not be able to practice their customary night probes of the American defenses. Eichelberger felt that he had the momentum and told General Swing to push on by the light of the full moon. At midnight, Lieutenant Colonel Wilson's 1/187th passed through the 188th and took up the lead. At 04:00 on 1 February, Wilson halted the march. Almost 20 hours after wading ashore at Nasugbu, the men slept for two hours and were up and off again up the road at 06:00.

At daybreak, 1/187th advance elements approached the Mount Cariliao-Mount Batulao pass. At the foot of Mount Cariliao was Mount Aiming. The three peaks gave the Japanese a perfect defensive position that dominated the highway. When they saw the 1/187th point advancing toward them, the Japanese opened up with artillery, mortars, and machine guns, the heaviest barrages that the 11th Airborne Division had encountered since its amphibious landing. The first fire from the heights around the road that slowed the division's advance appeared to be from a Japanese outpost. As 1/187th advanced, they ran up against the Japanese main line of resistance (MLR) across Highway 17, hinged on Mount Aiming and anchored on Mounts Cariliao and Batulao. The MLR was a string of caves, dugouts, and tank traps, all interconnected by a zigzag line of trenches, backed up with various artillery pieces manned by some 250 artillerymen emplaced to the north and east of Mount Aiming. Artillery rounds from these guns bracketed the highway. There were about 400 infantrymen in caves and trenches on Mount Aiming and across the highway. The defenses into which 1/187th had now run appeared to be the line to which the Japanese had been falling back; the Japanese were now ready to fight.

General Swing gave Colonel Soule the mission of reducing the Japanese stronghold on Mount Aiming. Soule in turn directed Lieutenant Colonel Wilson's 1/187th to lead the attack up the highway. He sent Lieutenant Colonel La Flamme's 1/188th to the left and north of the highway and Lieutenant Colonel Mann's 2/188th to the right and south. Lieutenant Colonels Hoska and Massad brought their 674th and 675th GFAB howitzers forward to support the infantry attack. The 188th's forward air control observer laid on close air support. The attack got underway at 09:00 when USAAF fighters and medium bombers strafed and bombed the Japanese positions. The artillery echelon fired concentrations on Japanese defensive positions and counter-battery fire on the artillery positions. At about noon, Captain Raymond F. Lee's A/188th charged up the hill, using rifles, bayonets, and hand grenades, and broke through the Japanese on Mount Aiming. The rifle company became separated from the rest of 1/188th and was forced to dig in. The Japanese counterattacked Lee's position all afternoon but failed to dislodge the Americans. Seizing Mount Aiming pierced and split the Japanese defenses in the area. While 1/188th held its position on the north flank, 2/188th moved south of the road and attacked the Japanese strongpoint between Mount Batulao and the highway. Meanwhile, 1/187th moved in between 1/188th and 2/188th and, as the center of the line, attacked eastward astride the highway. On the morning of 2 February, the 188th RCT launched an all-out attack to the east. At 08:30, the USAAF and the two artillery battalions hit the main Japanese positions between the two mountains. 1/187th and 2/188th continued the assault to the east, passing through 1/188th on Mount Aiming, protecting the 188th's left flank. The pace up the highway was slow initially but quickened as the Japanese were forced to withdraw with the capture of a regimental CP at Aga at 13:00, which showed the haste in which they departed. In the Aga-Caylaway area, the 188th RCT found between 75 and 100 tons of ammunition. In the defense of their CP, the Japanese had built three tank traps across the highway 20 feet (6.1 m) wide across the top, 4 feet (1.2 m) wide across the bottom, and 25 feet (7.6 m) deep, which the 127th AEB bridged. While 1/188th moved north, 2/188th continued to attack the Japanese in the northern foothills of Mount Batulao. So far, the division had lost six KIA and 41 WIA, and had killed about 90 Japanese. By dusk, the division butted up against the third and strongest position of the Japanese MLR across Highway 17. Throughout the night, the Japanese harassed the forward American units with artillery, mortar, and small-arms fire. The Japanese located the 675th GFAB's firing position and forced it to displace its guns.

The fight at the Mount Cariliao-Mount Batulao pass had slowed the division's advance up the Tagaytay Ridge and had prevented General Eichelberger from bringing in the 511th RCT a day early, on 2 February, instead of the originally planned 3 February. Eichelberger was under orders from General MacArthur not to bring in the 511th until he was certain that the division's amphibious units could link up with the paratroopers in less than 24 hours. Because of the delay at the Aga pass, Eichelberger reluctantly directed General Swing to bring in the 511th on 3 February. Eichelberger also ordered the US 24th Infantry Division to move a second battalion from the 19th Infantry Regiment from Leyte to Nasugbu to operate and protect the port and the MSR up Highway 17. This would free up 2/187th to join the rest of the 187th RCT on its march to Manila.

At 07:30 on the morning of 3 February, the 188th RCT, with 1/187th attached, attacked the third and final Japanese position in the stubbornly defended Mount Cariliao-Mount Batulao pass. The three battalions advanced rapidly against little resistance until 11:00. The lead 1/188th company rounded a bare ridge-nose on the north side of a sharp bend in Highway 17 on the western edge of Tagaytay Ridge and halted after observing Japanese activity on another bare ridge-nose south of the bend. General Pierson arrived and Lieutenant Colonel LaFlamme told him that his point men could see Japanese on the high ground to the south. Colonel Soule drove up and was discussing the situation with Pierson when all hell broke loose. The Japanese opened up with artillery, machine-gun, and small-arms fire. Pierson jumped into a roadside ditch and Soule jumped in on top of him. Soule received a shell fragment in his buttocks and commented to Pierson that he had been hit. Not only were Pierson and Soule pinned down by the artillery fire, but so were many other high-ranking officers, including General Eichelberger, General Francis W. Farrell (11th Airborne Division Artillery commander), and several colonels and lieutenant colonels on their staffs. In one of the barrages, 1/187th's Lieutenant Colonel Wilson was wounded. In all, the barrage resulted in eight KIA and 21 WIA. The artillery barrages forced everyone to take cover. Colonel Soule removed himself from the ditch and immediately assumed control of the attack on the Japanese position. He sent orders to bring up Wilson's 1/187th. Wilson ordered his lead company to swing around behind the Japanese position and take it from the rear. Lieutenant Colonel Mann led his 2/188th off the road to the south and onto the Japanese-held ridge. By 13:00, the troops of the 187th and 188th, using flamethrowers and hand grenades, supported by the guns of the 674th and 675th GFABs, wrestled control of the ridge from the Japanese, killing over 300 in the battle. The position was obviously an important one in the Japanese defensive plan; it was honeycombed with enormous supply tunnels, reinforced-concrete caves, and strong artillery and individual firing positions. With the reduction of Shorty Ridge, named after Colonel “Shorty” Soule, the amphibious units of the 11th Airborne Division that had landed and fought their way up a difficult route of attack were ready to make contact with the paratroopers of the 511th PIR.

The march to Manila continued.

Source citation: Flanagan (1997). The Rakkasans. pp. 76–84.

Jump on Tagaytay Ridge

At 08:15 on 3 February 1945, while the 188th RCT was reducing the Japanese resistance on Shorty Ridge, the paratroopers of the 511th RCT (less the 457th PFAB), began dropping from forty-eight C-47s onto the Tagaytay Ridge DZ. Because of a shortage of transport aircraft, only about one-third of the 511th RCT could be airdropped in one lift; the jump was planned for three waves delivered across two days. The first elements to be dropped consisted of Colonel Haugen and his regimental command group, Lieutenant Colonel Frank S. Holcomb's 2/511th PIR, and one-half of Lieutenant Colonel Edward H. Lahti's 3/511th PIR – about 915 officers and men overall. Tagaytay Ridge made an excellent DZ for a mass parachute drop. The area selected for the DZ was flat, over 4,000 yards (3,700 m) long and about 2,000 yards (1,800 m) wide. The only dangerous feature was the possibility of being blown off the ridge and down into Taal Lake. But that did not happen to any of the paratroopers. What did happen was that the first 18 planeloads of paratroopers landed right on DZs marked by smoke pots set out by advanced scouts. The second serial of thirty C-47s carrying 570 paratroopers dropped 6 miles (9.7 km) short of the drop point when its lead plane accidentally released a drop bundle and all paratroopers immediately "hit the silk." The second wave, under explicit orders to ignore the scattered parachutes on the ground persisted in jumping short.[4]:135 At about 12:10, when the rest of the regiment, the other half of 3/511th PIR and Major Henry A. Burgess' 1/511th PIR, came in over the ridge, some of the C-47s dropped their paratroopers on the parachutes from the premature airdrop. Only 425 men dropped onto the proper drop point; 1,325 landed between 4 miles (6.4 km) and 6 miles (9.7 km) to the east and northeast. Despite the scattered landings, the 511th RCT reassembled in about five hours, and by 13:00, made contact with the lead elements of the 188th RCT moving up Tagaytay Ridge.

Both Generals Eichelberger and Swing were with the 188th RCT's forward elements and contacted Colonel Haugen near the Manila Hotel Annex atop the ridge overlooking Taal Lake. That afternoon, 2/511th secured the DZ, and after 3/511th assumed DZ security, moved to the junction of Highways 17 and 25B to await further orders. The 11th Airborne Division CP moved into the Manila Hotel Annex, which was in a central position on the ridge and made a convenient control point for the troops moving east and north. Generals Eichelberger and Swing had hoped that the 511th RCT could move to the north and on to Manila in the afternoon, but there was not enough motor transport or gasoline available to permit it. Later in the afternoon, seventeen 2 1⁄2-ton cargo trucks were unloaded from landing craft at Nasugbu and sent forward. By 4 February, ten C-47s landed at Nasugbu's dirt airstrip, widened and cleared by the 127th AEB, with a cargo of gasoline that was immediately sent forward.

After dark on 3 February, anxious to start the movement toward Manila, General Swing sent First Lieutenant George Skau and 21 men from the Division Recon Platoon, mounted in jeeps, up Highway 17 to reconnoiter the road to Manila. Swing cautioned Skau that he was driving into unknown territory and to radio back as soon as he encountered Japanese defenses. At 04:00 on 4 February, Skau reported back that the road was secure as far as Imus, where the Japanese had blown the bridge and set up a defensive position, but he had found a dirt road that bypassed the bridge. It, too, had a bridge ready to be blown but the recon patrol had removed the charges. At 05:30, the 2/511th point moved out in two jeeps. Two hours later, the rest of 2/511th moved out. Lieutenant Colonel Holcomb and 2/511th secured the Imus River Bridge and moved over the Zapote River Bridge to the Las Pinas River Bridge. The Japanese had prepared to demolish the bridge but Holcomb's men caught them by surprise and took the bridge intact after a hard fight. The 511th RCT, by truck and on foot, moved forward and was now pushing against the southern Japanese defenses of Manila. At 08:15, the third serial of the 511th RCT airdrop, the 457th PFAB, dropped onto Tagaytay Ridge opposite the division CP. Meanwhile, back on Tagaytay Ridge, the 188th RCT with 1/187th attached, having cleaned out the Japanese on Shorty Ridge, left a company to secure the area and Colonel Soule led the rest of his command on foot toward Manila.