Pasig River

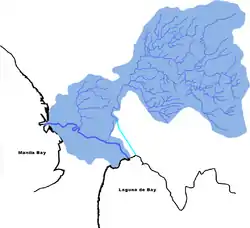

The Pasig River (Filipino: Ilog Pasig; Spanish: Río Pásig) is a river in the Philippines that connects Laguna de Bay to Manila Bay. Stretching for 25.2 kilometers (15.7 mi), it bisects the Philippine capital of Manila and its surrounding urban area into northern and southern halves. Its major tributaries are the Marikina River and San Juan River. The total drainage basin of Pasig River, including the basin of Laguna de Bay, covers 4,678 square kilometers (1,806 sq mi).[1]

| Pasig River | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

.svg.png.webp) Pasig River mouth .svg.png.webp) Pasig River (Philippines) | |

| Native name | Ilog Pasig (Tagalog) |

| Location | |

| Country | Philippines |

| Region | |

| Cities | |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Laguna de Bay |

| • location | Calabarzon |

| • coordinates | 14°31′33″N 121°06′33″E |

| Mouth | Manila Bay |

• location | Manila |

• coordinates | 14°35′40″N 120°57′20″E |

• elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Length | 25.2 km (15.7 mi) |

| Basin size | 4,678 km2 (1,806 sq mi)[1] |

| Discharge | |

| • maximum | 56 m3/s (2,000 cu ft/s) |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left |

|

| • right |

|

The Pasig River is technically a tidal estuary, as the flow direction depends upon the water level difference between Manila Bay and Laguna de Bay. During the dry season, the water level in Laguna de Bay is low with the river's flow direction dependent on the tides. During the wet season, when the water level of Laguna de Bay is high, the flow is reversed towards Manila Bay.

The Pasig River used to be an important transport route and source of water for Spanish Manila. Due to negligence and industrial development, the river has become very polluted and is considered biologically dead (i.e., unable to sustain life) by ecologists. The Pasig River Rehabilitation Commission (PRRC), which was established to oversee rehabilitation efforts for the river, is supported by private sector organisations such as the Clean and Green Foundation, Inc. that introduced the Piso para sa Pasig (Filipino: "A peso for Pasig") campaign in the 1990s.

Geography

The Pasig River winds generally northwestward for some 25 kilometers (15.5 mi) from the Laguna de Bay, the largest lake in the Philippines, to Manila Bay, in the southern part of the island of Luzon. From the lake, the river runs between Taguig and Taytay, Rizal, before entering Pasig. This portion of the Pasig River, to the confluence with the Marikina River tributary, is known as the Napindan River or Napindan Channel.

From there, the Pasig forms flows through Pasig until its confluence with the Taguig River, From here, it forms the border between Mandaluyong to the north and Makati to the south.. The river then sharply turns northeast, where it has become the border between Mandaluyong and Manila before turning again westward, joining its other major tributary, the San Juan River, and then following a sinuous path through the center of Manila before emptying into the bay.

The whole river and most portions of its tributaries lie entirely within Metro Manila, the metropolitan region of the capital. Isla de Convalecencia, the only island dividing the Pasig River, can be found in Manila and it is where the Hospicio de San Jose is located.

Tributaries and canals

One major river that drains Laguna de Bay is the Taguig River, which enters into Taguig before becoming the Pateros River; it is the border between the municipalities of Pateros and Makati City. Pateros River then enters the confluence where the Napindan Channel and Marikina River meet. The Marikina River is the larger of the two major tributaries of the Pasig River, and it flows southward from the mountains of Rizal and cuts through the Marikina Valley. The San Juan River drains the plateau on which Quezon City stands; its major tributary is Diliman Creek.

Within the city of Manila, various esteros (canals) criss-cross through the city and connect with the Tullahan River in the north and the Parañaque River to the west.

Crossings

.png.webp)

A total of 19 bridges currently cross the Pasig. The first bridge from the source at Laguna de Bay is the Napindan Bridge, followed by the Arsenio Jimenez Bridge to its west. Crossing the Napindan Channel in Pasig is the Bambang Bridge. The newest bridge, opened in February 2015, is the Buting-Sumilang Bridge that connects barangays Buting and Sumilang in Pasig.[2]

The next bridge downstream is the C-5 Road (Felix Manalo) Bridge connecting the cities of Makati and Pasig. Currently under construction is the Sta. Monica–Lawton Bridge, which will connect Lawton Avenue in Makati to Sta. Monica Street in Kapitolyo, Pasig as part of the Bonifacio Global City–Ortigas Link Road project approved in 2015.[3]

The Guadalupe Bridge between Makati and Mandaluyong carries Epifanio de los Santos Avenue, the major artery of Metro Manila, as well as the Manile Line 3 from Guadalupe station to Boni station. The Estrella–Pantaleon and Makati-Mandaluyong Bridges likewise connect the two cities downstream, with the latter forming the end of Makati Avenue.

The easternmost crossing in the City of Manila is Lambingan Bridge in the district of Santa Ana, followed by the Padre Zamora (Pandacan) Bridge connecting Pandacan and Santa Mesa districts, and carries the southern line of the Philippine National Railways. The Mabini Bridge (formerly Nagtahan Bridge) provides a crossing for Nagtahan Street, part of C-2 Road. Ayala Bridge carries Ayala Boulevard, and connects the Isla de Convalecencia to both banks of the Pasig.

Further downstream are the Quezon Bridge from Quiapo to Ermita, the Line 1 bridge from Central Terminal station to Carriedo station, MacArthur Bridge from Santa Cruz to Ermita, and the Jones Bridge from Binondo to Ermita. The last bridge near the mouth of the Pasig is the Roxas Bridge (also known as Mel Lopez Bridge and formerly called Del Pan Bridge) from San Nicolas to the Port Area and Intramuros.

The Metro Manila Skyway Stage 3 will serve as a connection road between North Luzon Expressway and South Luzon Expressway. The expressway bridge will be built within the city of Manila near the mouth of San Juan River where most parts of Skyway Stage 3 will be built and another bridge parallel to Pandacan and PNR bridges that will merge with NLEX Connector, and will serve as a solution to heavy traffic along EDSA. The project is expected to be finished by 2020.

Landmarks

The growth of Manila along the banks of the Pasig River has made it a focal point for development and historical events. The foremost landmark on the banks of the river is the walled district of Intramuros, located near the mouth of the river on its southern bank. It was built by the Spanish colonial government in the 16th century. Further upstream is the Hospicio de San Jose, an orphanage located on Pasig's sole island, the Isla de Convalescencia. On the northern bank stands the Quinta Market in Quiapo, Manila's central market, and Malacañan Palace, the official residence of the President of the Philippines. Also on Pasig River's northern bank and within the Manila district of Sta. Mesa is the main campus of the Polytechnic University of the Philippines.

In Makati City, along the southern bank of Pasig, is Circuit Makati (the former Sta. Ana Race Track) and the Rockwell Center, a high-end office and commercial area containing the Power Plant Mall. At the confluence of the Pasig and Marikina rivers is the Napindan Hydraulic Control Structure, which regulates the flow of water from the Napindan Channel.

Geology

The Pasig River's main watershed is concentrated in the plains between Manila Bay and Laguna de Bay. The watershed of the Marikina River tributary mostly occupies the Marikina Valley, which was formed by the Marikina Fault Line. The Manggahan Floodway is an artificially constructed waterway that aims to reduce the flooding in the Marikina Valley during the rainy season, by bringing excess water to the Laguna de Bay.

Tidal flows

The Pasig River is technically considered a tidal estuary. Toward the end of the summer or dry season (April and May), the water level in Laguna de Bay reaches to a minimum of 10.5 meters. During times of high tide, the water level in the lake may drop below that of Manila Bay's, resulting in a reverse flow of seawater from the bay into the lake. This results in increased pollution and salinity levels in Laguna de Bay at this time of the year.[4]

Flooding

The Pasig River is vulnerable to flooding in times of very heavy rainfall, with the Marikina River tributary the main source of the floodwater. The Manggahan Floodway was constructed to divert excess floodwater from the Marikina River into the Laguna de Bay, which serves as a temporary reservoir. By design, the Manggahan Floodway is capable of handling 2,400 cubic meters per second of water flow, with the actual flow being about 2,000 cubic meters per second. To complement the floodway, the Napindan Hydraulic Control System (NHCS) was built in 1983 at the confluence of the Marikina River and the Napindan Channel to regulate the flow of water between the Pasig River and the lake.[5]

History

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

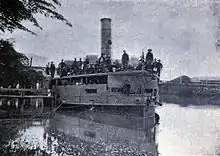

The Pasig River served as an important means of transport; it was Manila's lifeline and center of economic activity. Some of the most prominent kingdoms in early Philippine history, including the kingdoms of Namayan, Maynila, and Tondo grew up along the banks of the river, drawing their life and source of wealth from it. When the Spanish established Manila as the capital of their colonial properties in the Far East, they built the walled city of Intramuros on the southern bank of Pasig River near its mouth.

The commonly accepted origin for the endonym "Tagalog" is the term tagá-ilog, which means "people from [along] the river". An alternative theory states that the name is derived from tagá-alog, which means "people from the ford" (the prefix tagá- meaning "coming from" or "native of").[6] In 1821, American diplomat Edmund Roberts called the Tagalog Tagalor in his memoirs about his trips to the Philippines.[7]

The earliest written record of the Tagalog is a 9th-century document known as the Laguna Copperplate Inscription which is about a remission of debt on behalf of the ruler of Tondo.[8] Inscribed on it is year 822 of the Saka Era, the month of Waisaka, and the fourth day of the waning moon, which corresponds to Monday, April 21, 900 CE in the Proleptic Gregorian calendar.[9] The writing system used is the Kawi Script, while the language is a variety of Old Malay, and contains numerous loanwords from Sanskrit and a few non-Malay vocabulary elements whose origin may be Old Javanese. Some contend it is between Old Tagalog and Old Javanese.[9]

Pollution

After World War II, massive population growth, infrastructure construction, and the dispersal of economic activities to Manila's suburbs left the river neglected. The banks of the river attracted informal settlers and the remaining factories dumped their wastes into the river, making it effectively a huge sewer system. Industrialization had already polluted the river.[10]

In the 1930s, observers noticed the increasing pollution of the river, as fish migration from Laguna de Bay diminished. People ceased using the river's water for laundering in the 1960s, and ferry transport declined. By the 1970s, the river started to emanate offensive smells, and in the 1980s, fishing in the river was prohibited. By the 1990s, the Pasig River was considered biologically dead[10]

It is estimated that about 60-65 percent of the pollution in Pasig River comes from household waste disposed into the tributaries of the river. Increasing poverty in the rural areas in Philippines has driven migration to Metro Manila in search of better opportunities. This resulted in rapid urban growth, congestion and overcrowding of land and along the riverbanks, making the river and its tributaries a dumping ground for informal settlers living there. About 30-35 percent of the river pollution is generated from industries locating close to the river (such as tanneries, textile mills, food processing plants, distilleries, and chemical and metal plants), some of which do not have water treatment facilities which are capable of removing heavy metal pollutants. The rest of the pollutants consist of solid waste dumped into the rivers. Metro Manila has been reported to produce as much as 7,000 tons of garbage per day.[11]

Rehabilitation efforts

Efforts to revive the river began in December 1989 with the help of Danish authorities. The Pasig River Rehabilitation Program (PRRP) was established, with the Department of Environment and Natural Resources as the main agency with the coordination of the Danish International Development Assistance (DANIDA).[12]

In 1999, President Joseph Estrada signed Executive Order No. 54 establishing the PRRC to replace the old PRRP with additional expanded powers such as managing of wastes and resettling of squatters.[12]

In 2010, the TV network ABS-CBN and Pasig River Rehabilitation Commission headed by ABS-CBN Foundation-Bantay Kalikasan Director Gina Lopez – currently serving as a chairperson of PRRC – launched a fun run fund-raising activity called "Run for the Pasig River" held every month of October. The proceeds from the fun run will serve as a fund for the "Kapit-bisig para sa Ilog Pasig" (Collaborate for Pasig River) rehabilitation project of Pasig River.

In October 2018, the PRRC won the first Asia Riverprize, in recognition of its efforts to rehabilitate the Pasig River.[13][14] According to the PRRC, aquatic life has returned to the river.[13]

Gallery

Pasig River near Quiapo.

Pasig River near Quiapo. View from Fort Santiago.

View from Fort Santiago._01.JPG.webp) View from Guadalupe Bridge.

View from Guadalupe Bridge. Pasig River with the Old Post Office Building

Pasig River with the Old Post Office Building Boat transportation along Pasig River

Boat transportation along Pasig River

See also

References

- Tuddao Jr., Vicente B. (September 21, 2011). "Water Quality Management in the Context of Basin Management: Water Quality, River Basin Management and Governance Dynamics in the Philippines" (PDF). www.wepa-db.net. Department of Environment and Natural Resources. Retrieved 10 April 2017.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2015-02-16.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "NEDA Board Approved Projects (Aquino Administration) From June 2010 to June 2017" (PDF). National Economic and Development Authority Official Website. 2017-02-28. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-07-23. Retrieved 2018-09-06.

- "[Laguna de Bay] Lake Elevation". Laguna Lake Development Authority. Archived from the original on 2009-09-02.

- "Laguna de Bay Masterplan". Laguna Lake Development Authority. Archived from the original on 2007-09-29.

- "Tagalog, tagailog, Tagal, Katagalugan". English, Leo James. Tagalog-English Dictionary. 1990.

- Roberts, Edmund (1837). Embassy to the Eastern Courts of Cochin-China, Siam and Muscat. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 59.

- Ocampo, Ambeth (2012). Looking Back 6: Prehistoric Philippines. Mandaluyong City, Philippines: Anvil Publishing, Inc. pp. 51–56. ISBN 978-971-27-2767-2.

- Postma, Antoon (1992). "The Laguna Copper-Plate Inscription: Text and Commentary". Philippine Studies. 40 (2): 182–203. JSTOR 42633308.

- Murphy, Denis; Anana, Ted (2004). "Pasig River Rehabilitation Program". Habitat International Coalition. Archived from the original on 2007-10-12.

- Gorme, Joan B.; Maniquiz, Marla C.; Song, Pum; Kim, Lee-Hyung (2010). "The Water Quality of the Pasig River in the City of Manila, Philippines: Current Status, Management and Future Recovery". Environmental Engineering Research. 15 (3): 173–179. doi:10.4491/eer.2010.15.3.173.

- Santelices, Menchit. "A dying river comes back to life". Philippine Information Agency. Archived from the original on 2008-03-16.

- "'Instagrammable?' Restored Pasig River wins international environment award". ABS-CBN News. October 17, 2018. Retrieved 2018-10-20.

- "Pasig River rehabilitation program feted in first Asia RiverPrize awards". GMA News Online. October 17, 2018. Retrieved 2018-10-20.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pasig River. |