Binnen-I

| Part of a series on |

| Feminism |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Linguistics |

|---|

|

|

In German, a medial capital I (German: Binnen-I) is a non-standard, mixed case typographic convention used to indicate gender inclusivity for nouns having to do with people, by using a capital letter 'I' inside the word (Binnenmajuskel, literally "internal capital", i.e. camel case) surrounded by lower-case letters. An example is the word LehrerInnen ("teachers", both male and female). With a lower case I in that position, Lehrerinnen is just the standard word for "female teachers".

The Binnen-I is a non-standard solution for how to economically express a position of gender equality in one German word, with an expression that would otherwise require three words. Since English nouns (excluding pronouns) have no grammatical gender, words such as teacher(s), student(s), professor(s), and so on, can be used without implying the gender of the being(s) to which the noun refers. The situation in German, however, is more difficult since all nouns have one of three grammatical genders, masculine, feminine, or neuter.

When used with a noun designating a group of people, a Binnen-I indicates that the intended meaning of the word is both the feminine as well as the masculine forms, without having to write out both forms of the noun. It is formed from the feminine form of a noun containing the -in suffix (singular) or -innen suffix (plural). For example, Lehrerinnen (women teachers) would be written LehrerInnen, with the meaning (men and women) teachers, without having to write out both gender forms, or use the lexically unmarked masculine.

Other gender-inclusive typographic conventions exist in German that perform a similar function, such as the gender star.

Background

U.S. second wave

Part of the academic ferment in the United States in second-wave feminism in the 1970s was the attention paid to gender bias in language,[1] including "the uncovering of the gendered nature of many linguistic rules and norms" and how the use of language could be analyzed from a feminist viewpoint.[2] Studies showed the sexually biased use of language including "he" as a generic pronoun meaning both males and females[3][4] and how this wasn't just an outgrowth of natural language evolution but in fact was enforced by prescriptivist (male) grammarians.[4][5] By the 1980s and 1990s, feminist critique of language had spread to Germany[6] and other countries.

Nouns and gender

German has three genders: masculine, feminine, and neuter. With the exception of some relationship nouns (mother, father, daughter, etc.) that are tied to the sex of the person, the gender of a noun is arbitrary, and can be any one of the three;[7][lower-alpha 4] for example, masculine: Knoblauch (garlic); feminine: Steckrübe (turnip), Person (person); or neuter: Haus (house), Mädchen (girl).

In German, as to a lesser extent in English, some nouns designating people come in masculine/feminine pairs; in German they are often distinguished by an -in suffix in the feminine (Schauspieler/Schauspielerin), where English sometimes uses -ess (actor/actress). Similarly, in both languages the feminine form of such nouns is semantically marked and can only refer to a woman in each language, whereas the masculine form is unmarked and can designate either a man, if known, or an unknown person of indeterminate sex. In the plural, German generally has separate plurals for masculine and feminine (Juristen/Juristinnen: male attorneys/female attorneys).

In referring to a mixed (male/female) group of people, historically one would use the generic masculine, for example, Kollegen (masc. pl.; "colleagues"). To make it clear that both genders are included, one would use a three word phrase with the masculine and feminine versions of the noun joined by und ("and"), i.e., "Kolleginnen und Kollegen" (women colleagues and male colleagues).

History

Feminist Sprachkritik

At the end of the 1970s, groundbreaking work created the field of German feminist linguistics[lower-alpha 6] and critiqued both the inherent structure and usage of German on the one hand, and on the other, men's and women's language behavior, and concluded that German is antagonistic towards women (frauenfeindlich), for example, in the use of the generic masculine form when referring to mixed groups which makes women have no representation in the language, mirrors a "Man's world," and makes it seem like students, professors, employees, bosses, politicians, every group spoken about—is male, and women were invisible in the patterns of speech; and went on to say that language doesn't only mirror reality, it creates it.[1][8][9]

The use of medial capital I in Germany in this sense dates to the 1980s, in response to activism by German feminists for orthographic changes to promote gender equality in German writing. Some of this was called Frauendeutsch (women's German).

It is a solution to a problem of word economy: how do you avoid saying a three-word compound, e.g., Lehrer und Lehrerinnen (male teachers and female teachers) when you just want to say teachers in German? There are four methods, of varying levels of acceptance:

- Word pair with "and": Lehrer und Lehrerinnen (male teachers and female teachers); completely acceptable and standard

- Parentheses: Lehrer(in) (male teacher, (female teacher)); Pl: Lehrer(innen) (male teachers; (female teachers))

- Slash: Lehrer/in; Pl: Lehrer/innen

- internal-I: LehrerIn; pl: LehrerInnen

In 1990, this usage caused a kerfuffle in the Landtag of North Rhine-Westphalia, when an official complaint was lodged by the chair of the Free Democratic Party against the Green Party, who had used some words with medial capital I in some of their parliamentary motions, saying that it was "incorrect according to the German language". The President of the Landtag responded by declaring that printed documents destined to be distributed throughout the state had to follow the official Duden language standard, until such time that the Duden accepted the capital I. The same year, the Wiesbaden Magistrate recommended the use of medial capital I for municipal office use, and prohibited the use of purely masculine terminology. The Wiesbaden women's affairs officer said that this had already been standard usage by the mayor and by some departments and agencies by 1990.[10]

Usage and norms

Like French, Spanish, and other languages, but unlike English, the German language has a language academy, the Rat für deutsche Rechtschreibung[11] (Council for German Orthography) that watches over the language, and prescribes spelling and usage in official dictionaries and usage guides, and publishes occasional reforms to the standards like the 1996 spelling reform. The twelve-volume Duden dictionary and language reference is the officially recognized standard reference of the language, reflecting the views of the Spelling Council.

As Binnen-I is a typographic convention, it is seen in writing, and the internal capital I does not affect pronunciation of a word written with Binnen-I. However, in some cases, there is an attempt to indicate the convention in pronunciation, by using a glottal stop to create a momentary pause before the 'I'.

Other methods

Other nonstandard typographic conventions exist in German for promoting gender-inclusivity, including use of a slash, parentheses, an underscore (called the gender gap), or an asterisk (the gender star).

Gender star

The gender star is another recent, nonstandard typographic convention influenced by feminist linguistics. This convention uses an asterisk before the –innen suffix to perform the same function as the medial capital 'I' does for Binnen-I. Since the asterisk resembles a star, when used for this function, the asterisk is referred to as the Gendersternchen; literally, "little gender star".

The gender star was put forward as an improvement on the Binnen-I, which was seen as too beholden to the gender binary, whereas the asterisk allowed other, non-binary genders to be included.[12] It started off being used in universities, was then adopted by public administrations and other institutions, and finally ended up being officially adopted by the Green party in 2015 as a way to avoid discrimination against transgender and intersex individuals, and others. Since 2017, it is part of the official regulations of the Berlin Senate.[13]

Gender star was named German Anglicism of the Year in 2018. [14]

The gender star is pronounced by some people, who employ a glottal stop to mark it. The stop is sometimes placed at the beginning of the word, and sometimes in the middle, but never before suffixes.[12]

Luise Pusch criticized the gender star because it fails to get rid of the "linguistic invisibility of women". It symbolizes, as do the slash or the parenthesis typographic conventions, that women are "the second choice."[15]

See also

Notes

- FußgängerInnenzone (pedestrian zone) from Fußgänger (pedestrian) + Innen + Zone. The standard word for this in German is Fußgängerzone.

- Hundehalter is "dog owner", and HundehalterInnen is "male and female dog owners. In the full size image you can see AnrainerInnen (neighbors) as well. (The sign requests owners to keep their dogs from continuous barking for the sake of the neighbors.)

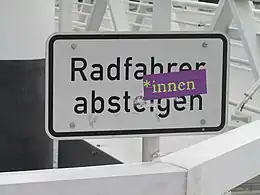

- Radfahrer is "bicyclist", and RadfahrerInnen with the medial capital I is "male and female bicyclists."

- Certain word suffixes like -lein, -ung, -chen and others are tied to a certain noun gender, so are not arbitrary in that sense.

- Pfadfinder is "[Boy] Scout" + Innen + Heim (shelter, hut, residence) gives PfadfinderInnenheim with Binnen-I, so: "Boy- and Girl Scouts trail shelter."

- These groundbreaking works were by the pioneers in German feminist linguistics, Senta Trömel-Plötz, and Luise F. Pusch.

Footnotes

- Stötzel 1995, p. 518.

- Holmes 2008, p. 551.

- Baron 1987, p. 6.

- Bodine 1975.

- Cameron 1998.

- Leue 2000.

- Hellinger 2013, p. 3.

- Klass 2010, p. 2–4.

- Brenner 2008, p. 5–6.

- Stötzel 1995, p. 537.

- Hammond, Alex (9 May 2013). "Ten things you might not have known about the English language". OUP English Language Teaching Global Blog. OUP. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- Stefanowitsch, Anatol (2018-06-09). "Gendergap und Gendersternchen in der gesprochenen Sprache" [Gender gap and gender star in spoken German]. Sprachlog (in German). Retrieved 2019-04-04.

- Steinhauer, Anja; Diewald, Gabriele (1 October 2017). Richtig gendern: Wie Sie angemessen und verständlich schreiben [Gendering correctly: How to Write Appropriately and Understandably]. Berlin: Bibliographisches Institut Duden. p. 46. ISBN 978-3-411-91250-6. OCLC 1011112208.

- "IDS: Corpus Linguistics: Anglicism of the Year 2018". Retrieved 2019-04-05.

- Pusch, Luise F. (8 March 2019). "Debatte Geschlechtergerechte Sprache. Eine für alle" [Debate Gender-appropriate language. One for all.]. TAZ (in German). Retrieved 2019-05-17.

References

- Baron, Dennis E. (July 1987). Grammar and Gender. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-03883-5. OCLC 780952035. Retrieved 15 February 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bodine, Anne (1975). "Androcentrism in prescriptive grammar: singular 'they', sex-indefinite 'he', and 'he or she'". Language in Society. 4 (2): 129–146. doi:10.1017/s0047404500004607. OCLC 4668940636.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brenner, Julia (2008). Männersprache / Frauensprache : geschlechtsspezifische Kommunikation [Men's Language/Women's Language: Gender-specific Communication] (student thesis) (in German). Munich: GRIN Verlag. ISBN 978-3-638-90475-9. OCLC 724724124. Retrieved 15 February 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bibliographisches Institut & F.A. Brockhaus (2011). Richtiges und gutes Deutsch: Das Wörterbuch der sprachlichen Zweifelsfälle [Correct and Good German: Usage Guide]. Der Duden in zwölf Bänden : das Standartwerk zur deutschen Sprache (in German). 9 (7., vollständig überarbeitete Auflage [completely revised 7th] ed.). Mannheim: Dudenverlag. p. 418. ISBN 978-3411040971. OCLC 800628904.

- Cameron, Deborah (1998). "9. Androcentrism in prescriptive grammar: singular 'they', sex-indefinite 'he', and 'he or she'". The Feminist Critique of Language: A Reader (2 ed.). London: Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-16400-9. OCLC 635293367. Retrieved 15 February 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hellinger, Marlis; Bußmann, Hadumod (10 April 2003). Gender Across Languages: The linguistic representation of women and men. Studies in language and Society, 11. 3. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 90-272-9681-2. OCLC 977855991. Retrieved 16 February 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hellinger, Marlis (8 March 2013). Sprachwandel und feministische Sprachpolitik: Internationale Perspektiven (in German). Opladen: West Deutscher Verlag. ISBN 978-3-322-83937-4. OCLC 715231718. Retrieved 15 February 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pauwels, Anne (15 April 2008). "24. Linguistic Sexism and Feminist Linguistic Activism". In Holmes, Janet; Meyerhoff, Miriam (eds.). The Handbook of Language and Gender. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-75670-6. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- Horny, Hildegard (1995). "13. Feministische Sprachkritik [Feminist Language Critique]". In Stötzel, Georg; Wengeler, Martin (eds.). Kontroverse Begriffe: Geschichte des öffentlichen Sprachgebrauchs in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland [Controversial Terms: History of Everyday Language in the Federal Republic of Germany] (in German). 4. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 517–562. ISBN 978-3-11-014106-1. OCLC 802718544. Retrieved 5 January 2018. Lay summary – University of Birmingham, German Studies (2004-01-03).

- Klass, Alex (2010). Die feministische Sprachkritik und ihre Auswirkungen auf die deutsche Gegenwartssprache [Feminist Linguistic Criticism and its Effect on Contemporary German] (in German). GRIN Verlag. ISBN 978-3-640-60500-2. OCLC 945944735. Retrieved 15 February 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Leue, Elisabeth (2000). "Gender And Language In Germany". Debatte: Journal of Contemporary Central and Eastern Europe. Routledge. 8 (2): 163–176. doi:10.1080/09651560020017206.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stötzel, Georg; Wengeler, Martin; Böke, Karin (1995). Kontroverse Begriffe: Geschichte des öffentlichen Sprachgebrauchs in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland (in German). 4. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-014106-1. OCLC 802718544. Retrieved 5 January 2018.

Further reading

- Hurley, Natasha and Susanne Luhmann. "The Capital »I«. Feminism, Language, Circulation" in: Abbt, Christine; Kammasch, Tim (2009). Punkt, Punkt, Komma, Strich?: Geste, Gestalt und Bedeutung philosophischer Zeichensetzung [Period, Period, Comma, Dash?: Gesture, Form, and Meaning of Philosophical Punctuation]. Edition Moderne Postmoderne. Bielefeld: Transcript. pp. 215–228. ISBN 978-3-89942-988-6. OCLC 427326653. Retrieved 23 March 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)