Liberal feminism

Liberal feminism, also called mainstream feminism, is a main branch of feminism defined by its focus on achieving gender equality through political and legal reform within the framework of liberal democracy. As the oldest of the "Big Three" schools of feminist thought,[1] liberal feminism has its roots in 19th century first-wave feminism that focused particularly on women's suffrage and access to education, and that was associated with 19th century liberalism and progressivism. Traditional liberal feminism has a strong focus on political and legal reforms aiming to give women equal rights and opportunities. Liberal feminists argue that society holds the false belief that women are, by nature, less intellectually and physically capable than men; thus it tends to discriminate against women in the academy, the forum, and the marketplace. Liberal feminists believe that "female subordination is rooted in a set of customary and legal constraints that blocks women's entrance to and success in the so-called public world", and strive for sexual equality via political and legal reform.[2] Liberal feminism "works within the structure of mainstream society to integrate women into that structure."[3]

| Part of a series on |

| Feminism |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Liberalism |

|---|

|

|

Liberal feminism is also called "mainstream feminism", "reformist feminism", "egalitarian feminism", or historically "bourgeois feminism", among other names.[4][5] As one of the "Big Three" schools of feminist thought,[1] liberal feminism is often contrasted with socialist/Marxist feminism and with radical feminism.[1][5][6][7][8][9] Liberal feminism and mainstream feminism are very broad terms, frequently taken to encompass all feminism that isn't radical or revolutionary socialist/Marxist, and that instead pursues equality through political, legal and social reform within a liberal democratic framework; as such liberal feminists may subscribe to a range of different feminist beliefs and political ideologies within the democratic spectrum from the centre-left to the centre-right. The broader liberal feminist tradition includes numerous, newer and often diverging sub fields such as equality feminism, social feminism, equity feminism, and difference feminism, but liberal feminism also remains a tradition of its own; Nordic state feminism belongs to the liberal tradition.[10]

Mainstream liberal feminism places great emphasis on the public world and typically supports laws and regulations that promote gender equality and ban practices that are discriminatory towards women; mainstream liberal feminists may also support social measures to reduce material inequality within a liberal democratic framework. Inherently pragmatic in orientation, liberal feminists have emphasized building far-reaching support for feminist causes among both women and men, and among the political centre, the government and legislatures. While rooted in first-wave feminism and traditionally focused on political and legal reform, the broader liberal feminist tradition may include parts of subsequent waves of feminism, especially third-wave feminism and fourth-wave feminism. The sunflower and the color gold became widely used symbols of liberal feminism and especially women's suffrage from the 1860s.[11]

Philosophy

Inherently pragmatic, liberal feminism does not have a clearly defined set of philosophies. Liberal feminists tend to focus on practical reforms of laws and policies in order to achieve equality; liberal feminism has a more individualistic approach to justice than left-wing branches of feminism such as socialist or radical feminism.[12] Susan Wendell argues that "liberal feminism is an historical tradition that grew out of liberalism, as can be seen very clearly in the work of such feminists as Mary Wollstonecraft and John Stuart Mill, but feminists who took principles from that tradition have developed analyses and goals that go far beyond those of 18th and 19th century liberal feminists, and many feminists who have goals and strategies identified as liberal feminist [...] reject major components of liberalism" in a modern or party-political sense; she highlights "equality of opportunity" as a defining feature of liberal feminism.[12]

Political liberalism gave feminism a familiar platform for convincing others that their reforms "could and should be incorporated into existing law".[13] Liberal feminists argued that women, like men, be regarded as autonomous individuals, and likewise be accorded the rights of such.[13]

History

The goal for liberal feminists beginning in the late 18th century was to gain suffrage for women with the idea that this would allow them to gain individual liberty. They were concerned with gaining freedom through equality, diminishing men's cruelty to women, and gaining opportunities to become full persons.[14] They believed that no government or custom should prohibit the due exercise of personal freedom. Early liberal feminists had to counter the assumption that only white men deserved to be full citizens. Pioneers such as Mary Wollstonecraft, Judith Sargent Murray, and Frances Wright advocated for women's full political inclusion.[14] In 1920, after nearly 50 years of intense activism, women were finally granted the right to vote and the right to hold public office in the United States, and in much of the Western world within a few decades before or a few decades after this time.

Liberal feminism was largely quiet in the United States for four decades after winning the vote. In the 1960s during the civil rights movement, liberal feminists drew parallels between systemic race discrimination and sex discrimination.[2] Groups such as the National Organization for Women, the National Women's Political Caucus, and the Women's Equity Action League were all created at that time to further women's rights. In the U.S., these groups have worked, thus far unsuccessfully, for the ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment or "Constitutional Equity Amendment", in the hopes it will ensure that men and women are treated as equals under the law. Specific issues important to liberal feminists include but are not limited to reproductive rights and abortion access, sexual harassment, voting, education, fair compensation for work, affordable childcare, affordable health care, and bringing to light the frequency of sexual and domestic violence against women.[15]

Historically, liberal feminism, also called "bourgeois feminism", was mainly contrasted with the working-class or "proletarian" women's movements, that eventually developed into called socialist and Marxist feminism. Since the 1960s both liberal feminism and the "proletarian" or socialist/Marxist women's movements are also contrasted with radical feminism. Liberal feminism is usually included as one of the two, three or four main traditions in the history of feminism.[16][5]

Individualist or libertarian feminism is sometimes grouped as one of many branches of feminism with historical roots in liberal feminism, but tends to diverge significantly from mainstream liberal feminism on many issues. For example, "libertarian feminism does not require social measures to reduce material inequality; in fact, it opposes such measures [...] in contrast, liberal feminism may support such requirements and egalitarian versions of feminism insist on them."[17] Unlike many libertarian feminists, mainstream liberal feminists oppose prostitution; for example the mainstream liberal Norwegian Association for Women's Rights supports the ban on buying sexual services.[18]

Writers

Feminist writers associated with this theory include Mary Wollstonecraft, John Stuart Mill, Helen Taylor, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Gina Krog; Second Wave feminists Betty Friedan, Gloria Steinem, Simone de Beauvoir; and Third Wave feminist Rebecca Walker.

- Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797) has been very influential in her writings as A Vindication of the Rights of Woman commented on society's view of women and encouraged women to use their voices in making decisions separate from decisions previously made for them. Wollstonecraft "denied that women are, by nature, more pleasure seeking and pleasure giving than men. She reasoned that if they were confined to the same cages that trap women, men would develop the same flawed characters. What Wollstonecraft most wanted for women was personhood."[2] She argued that patriarchal oppression is a form of slavery that could no longer be ignored . Wollstonecraft argued that the inequality between men and women existed due to the disparity between their educations. Along with Judith Sargent Murray and Frances Wright, Wollstonecraft was one of the first major advocates for women's full inclusion in politics.

- Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815–1902) was one of the most influential women in first wave feminism. An American social activist, she was instrumental in orchestrating the Seneca Falls Convention, the first women's rights convention, which was held in Seneca Falls, New York. Not only was the suffragist movement important to Stanton, she also was involved in women's parental and custody rights, divorce laws, birth control, employment and financial rights, among other issues.[19] Her partner in this movement was the equally influential Susan B. Anthony. Together, they fought for a linguistic shift in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to include "female".[20] Additionally, in 1890 she founded the National American Woman Suffrage Association and presided as president until 1892.[20] She produced many speeches, resolutions, letters, calls, and petitions that fed the first wave and kept the spirit alive.[21] Furthermore, by gathering a large number of signatures, she aided the passage of the Married Women's Property Act of 1848 which considered women legally independent of their husbands and granted them property of their own. Together these women formed what was known as the NWSA (National Women Suffrage Association), which focused on working legislatures and the courts to gain suffrage.

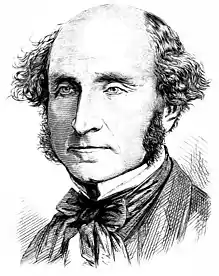

- John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (May 20, 1806 – May 8, 1873) believed that both sexes should have equal rights under the law and that "until conditions of equality exist, no one can possibly assess the natural differences between women and men, distorted as they have been. What is natural to the two sexes can only be found out by allowing both to develop and use their faculties freely."[22] Mill frequently spoke of this imbalance and wondered if women were able to feel the same "genuine unselfishness" that men did in providing for their families. This unselfishness Mill advocated is the one "that motivates people to take into account the good of society as well as the good of the individual person or small family unit".[2] Similar to Mary Wollstonecraft, Mill compared sexual inequality to slavery, arguing that their husbands are often just as abusive as masters, and that a human being controls nearly every aspect of life for another human being. In his book The Subjection of Women, Mill argues that three major parts of women's lives are hindering them: society and gender construction, education, and marriage.[23] He also argues that sex inequality is greatly inhibiting the progress of humanity.

Notable liberal feminists

- 18th century

- 19th century

- 20th century

Organizations

National Organization for Women

The National Organization for Women (NOW) is the largest liberal feminist organization in the United States. It supports the Equal Rights Amendment, reproductive rights including freer access to abortion, as well as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender rights (LGBT rights), and economic justice. It opposes violence against women and racism.

Various other issues the National Organization for Women also deals with are:

|

|

National Women's Political Caucus

The National Women's Political Caucus (NWPC), founded in 1971, is the only national organization dedicated exclusively to increasing women's participation in all areas of political and public life as elected and appointed officials, as delegates to national party conventions, as judges in the state and federal courts, and as lobbyists, voters and campaign organizers.[25]

Founders of NWPC include such prominent women as Gloria Steinem, author, lecturer and founding editor of Ms. Magazine; former Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm; former Congresswoman Bella Abzug; Dorothy Height, former president of the National Council of Negro Women; Jill Ruckelshaus, former U.S. Civil Rights Commissioner; Ann Lewis, former Political Director of the Democratic National Committee; Elly Peterson, former vice-chair of the Republican National Committee; LaDonna Harris, Indian rights leader; Liz Carpenter, author, lecturer and former press secretary to Lady Bird Johnson; and Eleanor Holmes Norton, Delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives and former chair of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

These women were spurred by Congress' failure to pass the Equal Rights Amendment in 1970. They believed legal, economic and social equity would come about only when women were equally represented among the nation's political decision-makers. Their faith that women's interests would best be served by women lawmakers has been confirmed time and time again, as women in Congress, state legislatures and city halls across the country have introduced, fought for and won legislation to eliminate sex discrimination and meet women's changing needs.[25]

Women's Equity Action League

The Women's Equity Action League (WEAL) was a national membership organization, with state chapters and divisions, founded in 1968 and dedicated to improving the status and lives of women primarily through education, litigation, and legislation. It was a more conservative organization than NOW and was formed largely by former members of that organization who did not share NOW's assertive stance on socio-sexual issues, particularly on abortion rights. WEAL spawned a sister organization, the Women's Equity Action League Fund, which was incorporated in 1972 "to help secure legal rights for women and to carry on educational and research projects on sex discrimination". The two organizations merged in 1981 following changes in the tax code.[26] WEAL dissolved in 1989[27]

The stated purposes of WEAL were:

- to promote greater economic progress on the part of American women;

- to press for full enforcement of existing anti-discriminatory laws on behalf of women;

- to seek correction of de facto discrimination against women;

- to gather and disseminate information and educational material;

- to investigate instances of, and seek solutions to, economic, educational, tax, and employment problems affecting women;

- to urge that girls be prepared to enter more advanced career fields;

- to seek reappraisal of federal, state and local laws and practices limiting women's employment opportunities;

- to combat by all lawful means, job discrimination against women in the pay, promotional or advancement policies of governmental or private employers;

- to seek the cooperation and coordination of all American women, individually or as organizations *to attain these objectives, whether through legislation, litigation, or other means, and by doing any and all things necessary or incident thereto.

Norwegian Association for Women's Rights

Norway has had a tradition of government-supported liberal feminism since 1884, when the Norwegian Association for Women's Rights (NKF) was founded with the support of the progressive establishment within the then-dominant governing Liberal Party (which received 63.4% of the votes in the election the following year). The association's founders included five Norwegian prime ministers, and several of its early leaders were married to prime ministers. Rooted in first-wave liberal feminism, it works "to promote gender equality and women's and girls' human rights within the framework of liberal democracy and through political and legal reform".[28] NKF members had key roles in developing the government apparatus and legislation related to gender equality in Norway since 1884; with the professionalization of gender equality advocacy from 1970s, the "Norwegian government adopted NKF's [equality] ideology as its own"[10] and adopted laws and established government institutions such as the Gender Equality Ombud based on NKF's proposals; the new government institutions to promote gender equality were also largely built and led by prominent NKF members such as Eva Kolstad, NKF's former president and the first Gender Equality Ombud. NKF's feminist tradition has often been described as Norway's state feminism. The term state feminism itself was coined by NKF member Helga Hernes.[10] Although it grew out of 19th century progressive liberalism, Norwegian liberal feminism is not limited to liberalism in a modern party-political sense, and NKF is broadly representative of the democratic political spectrum from the centre-left to the centre-right, including the social democratic Labour Party. Norwegian supreme court justice and former NKF President Karin Maria Bruzelius has described NKF's liberal feminism as "a realistic, sober, practical feminism".[29]

Other organizations

The Equal Rights Amendment

A fair number of American liberal feminists believe that equality in pay, job opportunities, political structure, social security, and education for women especially needs to be guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution.

Three years after women won the right to vote, the Equal Right Amendment (ERA) was introduced in Congress by Senator Charles Curtis Curtis and Representative Daniel Read Anthony Jr., both Republicans. This amendment stated that civil rights cannot be denied on the basis of one's sex. It was authored by Alice Paul, head of the National Women's Party, who led the suffrage campaign. Through the efforts of Alice Paul, the Amendment was introduced into each session of the United States Congress. But it was buried in committee in both Houses of Congress. In 1946, it was narrowly defeated by the full Senate, 38–35. In February 1970, twenty NOW leaders disrupted the hearings of the U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Constitutional Amendments, demanding the ERA be heard by the full Congress. In May of that year, the Senate Subcommittee began hearings on the ERA under Senator Birch Bayh. In June, the ERA finally left the House Judiciary Committee due to a discharge petition filed by Representative Martha Griffiths. In March 1972, the ERA was approved by the full Senate without changes, 84–8. Senator Sam Ervin and Representative Emanuel Celler succeeded in setting a time limit of seven years for ratification. The ERA then went to the individual states for approval but failed to win in enough of them (38) to become law. In 1978, Congress passed a disputed (less than supermajority) three year extension on the original seven year ratification limit, but the ERA could not gain approval by the needed number of states.[30]

The state legislatures that were most hostile to the ERA were Utah, Florida, Illinois, North Carolina, and Oklahoma. The NOW holds that the single most obvious problem in passing the ERA was the gender and racial imbalance in the legislatures. More than 2/3 of the women and all of the African Americans in state legislatures voted for the ERA, but less than 50% of the white men in the targeted legislatures cast pro-ERA votes in 1982.[31]

Equity feminism

Equity feminism is a form of liberal feminism discussed since the 1980s,[32][33] specifically a kind of classically liberal or libertarian feminism, emphasizing equality under law, equal freedoms, and rights, rather than profound social transformations.[34]

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy refers to Wendy McElroy, Joan Kennedy Taylor, Cathy Young, Rita Simon, Katie Roiphe, Diana Furchtgott-Roth, Christine Stolba, and Christina Hoff Sommers as equity feminists.[34] Steven Pinker, an evolutionary psychologist, identifies himself as an equity feminist, which he defines as "a moral doctrine about equal treatment that makes no commitments regarding open empirical issues in psychology or biology".[35] Barry Kuhle asserts that equity feminism is compatible with evolutionary psychology, in contrast to gender feminism.[36]

Critics

Main critiques

Critics of liberal feminism argue that its individualist assumptions make it difficult to see the ways in which underlying social structures and values disadvantage women. They argue that even if women are not dependent upon individual men, they are still dependent upon a patriarchal state. These critics believe that institutional changes, like the introduction of women's suffrage, are insufficient to emancipate women.[37]

One of the more prevalent critiques of liberal feminism is that it, as a study, allows too much of its focus to fall on a "metamorphosis" of women into men, and in doing so, it disregards the significance of the traditional role of women.[2] One of the leading scholars who have critiqued liberal feminism is radical feminist Catherine A. MacKinnon, an American lawyer, writer, and social activist. Specializing in issues regarding sex equality, she has been intimately involved in the cases regarding the definition of sexual harassment and sex discrimination.[8] She, among other radical feminist scholars, views liberalism and feminism as incompatible, because liberalism offers women a "piece of the pie as currently and poisonously baked".[38]

bell hooks' main criticism of the philosophies of liberal feminism is that they focus too much on equality with men in their own class.[39] She maintains that the "cultural basis of group oppression" is the biggest challenge, in that liberal feminists tend to ignore it.[39]

White woman's burden

Another important critique of liberal feminism posits the existence of a "white woman's burden" or white savior complex. The phrase "white woman's burden" derives from "The White Man's Burden". Critics such as Black feminists and postcolonial feminists assert that mainstream liberal feminism reflects only the values of middle-class, heterosexual, white women and fails to appreciate the position of women of different races, cultures, or classes.[40] With this, white liberal feminists reflect the issues that underlie the White savior complex. They do not understand women that are outside the dominant society but try to "save" or "help" them by pushing them to assimilate to their ideals of feminism. According to such critics liberal feminism fails to recognize the power dynamics that are in play with women of color and transnational women which involve multiple sources of oppression.

Literature

- Johnson, Pauline. "Normative tensions of Contemporary Feminism"[41]Thesis Eleven JournalMay, 2010.

- Kensinger, Loretta. "In Quest of Liberal Feminism"[42] Hypatia 1997.

- McCloskey, Deirdre. "Free-Market Feminism 101"[43] Eastern Economic Journal2000.

- Code, Lorraine. "Encyclopedia Of Feminist Theories" Taylor and Francis Group2014.

- Dundes, Lauren. "Concerned, Meet Terrified: Intersectional Feminism and the Women's March" Women's Studies International Forum July 2018.

References

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Feminism/Liberal Feminism |

- Maynard, Mary (1995). "Beyond the 'big three': the development of feminist theory into the 1990s". Women's History Review. 4 (3): 259–281.

- Tong, Rosemarie (1992). "Liberal feminism". Feminist thought: a comprehensive introduction. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415078740.

- West, Rebecca. "Kinds of Feminism". University of Alabama in Huntsville.

- Lindsey, Linda L. (2015). Gender Roles: A Sociological Perspective. Routledge. p. 17. ISBN 9781317348085.

- Voet, Rian (1998). "Categorizations of feminism". Feminism and Citizenship. SAGE. p. 25. ISBN 1446228045.

- Murphy, Meghan (April 11, 2014). "The divide isn't between 'sex negative' and 'sex positive' feminists — it's between liberal and radical feminism". Feminist Current. Retrieved December 24, 2017.

- Appignanesi, Richard; Garratt, Ghris (1995). Postmodernism for beginners. Trumpington: Icon. pp. 100–101. ISBN 9781874166214.

- MacKinnon, Catharine A. (2013). "Sexuality". In Kolmar, Wendy K.; Barkowski, Frances (eds.). Feminist theory: a reader (4th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Higher Education. ISBN 9780073512358.

- Gail Dines (29 June 2011). Gail Dines on radical feminism (Video). Wheeler Centre, Sydney Writers' Festival, Melbourne via YouTube. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- Elisabeth Lønnå: Stolthet og kvinnekamp: Norsk kvinnesaksforenings historie fra 1913, Gyldendal Norsk Forlag, 1996, p. 273, passim, ISBN 8205244952

- Cheris Kramarae & Paula A. Treichler (eds.), Amazons, Bluestockings and Crones: A Feminist Dictionary, Pandora Press, 1992

- Wendell, Susan (June 1987). "A (Qualified) Defense of Liberal Feminism". Hypatia. 2 (2): 65–93. doi:10.1111/j.1527-2001.1987.tb01066.x. ISSN 0887-5367.

- Musgrave, L. Ryan (2003-11-01). "Liberal Feminism, from Law to Art: The Impact of Feminist Jurisprudence on Feminist Aesthetics". Hypatia. 18 (4): 214–235. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.582.4459. doi:10.1111/j.1527-2001.2003.tb01419.x. ISSN 1527-2001. S2CID 22580016.

- Marilley, Suzanne M. (1996). "The feminism of equal rights". Woman suffrage and the origins of liberal feminism in the United States, 1820-1920. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 1–10. ISBN 9780674954656.

- hooks, bell. "Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center" Cambridge, MA: South End Press 1984

- Artwińska, Anna (2020). Gender, Generations, and Communism in Central and Eastern Europe and Beyond. Routledge.

- Mahowald, Mary Briody (1999). Genes, Women, Equality. Oxford University Press. p. 145.

- "Behold sexkjøpsloven". Norwegian Association for Women's Rights. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- Baker, Jean H. (2005). Sisters: the lives of America's suffragists. New York: Hill and Wang. ISBN 9780809095285.

- Evans, Sara M. (1997). Born for liberty: a history of women in America. New York, New York: Free Press Paperbacks. ISBN 9780684834986.

- Stanton, Elizabeth Cady (1994). "Address to the New York State Legislature, 1854". In Schneir, Miriam (ed.). Feminism: the essential historical writings. New York: Vintage Books. p. 110. ISBN 9780679753810.

- Mill, John Stuart (2013) [1869]. The Subjection of Women (A Feminist Literature Classic). Cork: e-artnow Editions. ISBN 9788074843150.

- Brink, David (9 October 2007). "Mill's Moral and Political Philosophy". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University.

- Interview with Nadine Strossen, Wikinews, Retrieved 12 June 2020

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-10-29. Retrieved 2014-12-14.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Women's Equity Action League. Records of the Women's Equity Action League, 1966-1979: A Finding Aid". oasis.lib.harvard.edu.

- Kraft, Katherine Gray; Stickney, Zephorene L. "Women's Equity Action League. Records of the Women's Equity Action League, 1966-1979: A Finding Aid". Oasis. Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- "About us". Norwegian Association for Women's Rights. Retrieved 2020-10-24.

- "Hvem vi er". Norwegian Association for Women's Rights. Retrieved 2020-10-28.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-08-07. Retrieved 2007-07-31.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Black, Naomi (1989). Social feminism. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780801422614.

- Halfmann, Jost (1989). "Social change and political mobilization in West Germany". In Katzenstein, Peter (ed.). Industry and politics in West Germany: toward the Third Republic. Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press. p. 79. ISBN 9780801495953.

Quote: Equity-feminism differs from equality-feminism in the depth and scope of its strategic goals. A feminist revolution would pursue three goals, according to Herrad Schenk:

- Citing:

- Schenk, Herrad (1980). Die feministische Herausforderung: 150 Jahre Frauenbewegung in Deutschland. München: Beck. ISBN 9783406060137.

English translation: ...the abolition of the gender-specific division of work in the family, the dissolution of the psychic foundations of different gender roles, and the feminization of the societal system of norms and values.

- Schenk, Herrad (1980). Die feministische Herausforderung: 150 Jahre Frauenbewegung in Deutschland. München: Beck. ISBN 9783406060137.

- "Liberal Feminism". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 18 October 2007. Retrieved 24 February 2016. (Revised 30 September 2013.)

- Pinker, Steven (2002). "Gender". The blank slate: the modern denial of human nature. New York: Viking. p. 341. ISBN 9780142003343.

- Kuhle, Barry X. (January 2012). "Evolutionary psychology is compatible with equity feminism, but not with gender feminism: A reply to Eagly and Wood". Evolutionary Psychology. 10 (1): 39–43. doi:10.1177/147470491201000104. PMID 22833845.

- See also:

- Eagly, Alice H.; Wood, Wendy (May 2011). "Feminism and the evolution of sex differences and similarities". Sex Roles. 64 (9–10): 758–767. doi:10.1007/s11199-011-9949-9. S2CID 144177655.

- Bryson, Valerie (1999). Feminist debates: issues of theory and political practice. New York: New York University Press. pp. 14–15. ISBN 9780814713488.

- Morgan, Robin (1996). "Light bulbs, radishes and the politics of the 21st century". In Bell, Diane; Klein, Renate (eds.). Radically speaking: feminism reclaimed. Chicago: Spinifex Press. pp. 5–8. ISBN 9781742193649.

- "bell hooks' "Feminist Theory: From Margin To Center": Chapter 2". Loftier Musings. 2012-06-18. Retrieved 2018-12-04.

- Mills, Sara (1998). "Postcolonial feminist theory". In Jackson, Stevi; Jones, Jackie (eds.). Contemporary feminist theories. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 98–112. ISBN 9780748606894.

- https://files.zotero.net/16332415126/Johnson%20-%202010%20-%20Normative%20Tensions%20of%20Contemporary%20Feminism.pdf

- Kensinger, Loretta (1997). "(In)Quest of Liberal Feminism". Hypatia. 12 (4): 178–197. doi:10.1111/j.1527-2001.1997.tb00303.x. JSTOR 3810738.

- McCloskey, Deirdre N. (2000). "Free-Market Feminism 101". Eastern Economic Journal. 26 (3): 363–365. JSTOR 40326003.

.jpg.webp)