Culture of Brazil

The culture of Brazil is primarily Western and is derived from Portuguese culture,[1] but presents a very diverse nature showing that an ethnic and cultural mixing occurred in the colonial period involving mostly Indigenous people of the coastal and most accessible riverine areas, Portuguese people and African people. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, together with further waves of Portuguese colonization, Italians, Spaniards, Germans, Austrians, Levantine Arabs (Syrians and Lebanese), Armenians, Japanese, Chinese, Koreans, Greeks, Poles, Helvetians, Ukrainians and Russians settled in Brazil, playing an important role in its culture as it started to shape a multicultural and multiethnic society.[2]

As consequence of three centuries of colonization by the Portuguese empire, the core of Brazilian culture is derived from the culture of Portugal. The numerous Portuguese inheritances include the language, cuisine items such as rice and beans and feijoada, the predominant religion and the colonial architectural styles.[3] These aspects, however, were influenced by African and Indigenous American traditions, as well as those from other Western European countries.[4] Some aspects of Brazilian culture are contributions of Italian, Spaniard, German, Japanese and other European immigrants.[5] Amerindian people and Africans played a large role in the formation of Brazilian language, cuisine, music, dance and religion.[5][6]

This diverse cultural background has helped show off many celebrations and festivals that have become known around the world, such as the Brazilian Carnival and the Bumba Meu Boi. The colourful culture creates an environment that makes Brazil a popular destination for many tourists each year, around over 1 million.[7]

History

Brazil was a colony of Portugal for over three centuries. About a million Portuguese settlers arrived during this period [8] and brought their culture to the colony. The Indigenous inhabitants of Brazil had much contact with the colonists. Many became extinct, others mixed with the Portuguese. For that reason, Brasil also holds Amerindian influences in its culture, mainly in its food and language. Brazilian Portuguese has hundreds of words of Indigenous American origin, mainly from the Old Tupi language.[9]

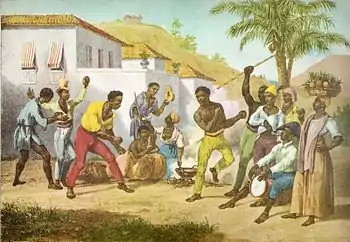

Black Africans, who were brought as slaves to Brazil, also participated actively in the formation of Brazilian culture. Although the Portuguese colonists forced their slaves to convert to Catholicism and speak Portuguese their cultural influences were absorbed by the inhabitants of Brazil of all races and origins. Some regions of Brazil, especially Bahia, have particularly notable African inheritances in music, cuisine, dance and language.[10]

Immigrants from Italy, Germany, Spain, Japan, Ukraine, Russia, Poland, Austria-Hungary and the Middle East played an important role in the areas they settled (mostly Southern and Southeastern Brazil). They organized communities that became important cities such as Joinville, Caxias do Sul, Blumenau, Curitiba and brought important contributions to the culture of Brazil.[11][12]

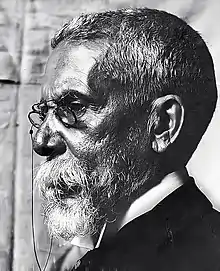

Modernism in Brazil started with the Modern Art Week held in São Paulo in 1922 and was characterized by experimentation and interest in Brazilian society and culture, as well as rebellion against influence from Europe and the United States and the orthodoxy of the Brazilian Academy of Letters.[13] Tarsila do Amaral and Oswald de Andrade were among the catalysts of the antropofagia movement in Brazil, with works such as Manifesto Pau-Brasil, Abaporu, and Manifesto Antropófago.[13][14] In the 1930s, sociologists such as Gilberto Freyre and Sérgio Buarque de Holanda published ideas about Brazilian culture, society, and identity, presenting concepts such as "racial democracy" and the "cordial man."[15]

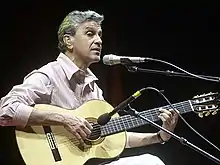

Another important 20th century cultural movement was Tropicália or Tropicalismo, a movement against the repression of different forms of authorianism, including the Military dictatorship in Brazil and the Catholic Church.[16] Part of the counterculture of the 1960s, Tropicalismo was led by figures such as Gilberto Gil and Caetano Veloso and manifested itself primarily in music.[17]

Language

The official language of Brazil is Portuguese. It is spoken by about 99% of the population, making it one of the strongest elements of national identity.[18] There are only some Amerindian groups and small pockets of immigrants who do not speak Portuguese.

Similarly to American English and Canadian French, Brazilian Portuguese is more phonetically conservative or archaic than the language of the colonizing metropolis, maintaining several features that European

Portuguese had before the 19th century.[19][20][21][22] Also similarly to the American English, the Brazilian regional variation as well as the European one include a small number of words of Indigenous American and African origin, mainly restricted to place names and fauna and flora.[23]

Minority languages are spoken throughout the nation. One hundred and eighty Amerindian languages are spoken in remote areas and a number of other languages are spoken by immigrants and their descendants. There are significant communities of German (mostly the Hunsrückisch, a High German language dialect) and Italian (mostly the Talian dialect, of Venetian origin) speakers in the south of the country, both of which are influenced by the Portuguese language.[24][25] Not to mention the Slavic communities, Ukrainians and Poles which are also part of these minority languages.

The Brazilian Sign Language (not signed Portuguese – it likely is descended from the French Sign Language), known by the acronym LIBRAS, is officially recognized by law, albeit using it alone would convey a very limited degree of accessibility, throughout the country.

Religion

About 2/3 of the population are Roman Catholics. Catholicism was introduced and spread largely by the Portuguese Jesuits, who arrived in 1549 during the colonization with the mission of converting the Indigenous people. The Society of Jesus played a large role in the formation of Brazilian religious identity until their expulsion of the country by the Marquis of Pombal in the 18th century.[28]

In recent decades Brazilian society has witnessed a rise in Protestantism. Between 1940 and 2010, the percentage of Roman Catholics fell from 95% to 64.6%, while the various Protestant denominations rose from 2.6% to 22.2%.[29]

Carnaval

.jpg.webp)

The Brazilian Carnaval is an annual festival held forty-six days before Easter. Carnival celebrations are believed to have roots in the pagan festival of Saturnalia, which, adapted to Christianity, became a farewell to bad things in a season of religious discipline to practice repentance and prepare for Christ's death and resurrection.

Carnaval is the most famous holiday in Brazil and has become an event of huge proportions. For almost a week festivities are intense, day and night, mainly in coastal cities.[31]

The typical genres of music of Brazilian carnival are: samba-enredo and marchinha (in Rio de Janeiro and Southeast Region), frevo, maracatu and Axé music (in Pernambuco, Bahia and Northeast Region)

Cuisine (Gastronomy)

Brazilian cuisine varies greatly by region. This diversity reflects the country's history and mix of indigenous and immigrant cultures. This has created a national cooking style, marked by the preservation of regional differences.[32] Since the imperial period,[33] the feijoada, a Portuguese stew with origins in Ancient Rome, has been the country's national dish.[34][35] Luís da Câmara Cascudo wrote that, having been revised and adapted in each region of the country, it is no longer just a dish, but has become a complete food.[36]

Brazil has a variety of candies including brigadeiros, made with condensed milk, butter, cocoa powder, and it can have sprinkles of chocolate around, and beijinhos. Other snack foods include coxinhas, churrasco, sfiha, empanadas, and pine nuts (in Festa Junina). Pão de queijo are typical in the state of Minas Gerais. Typical northern foods include pato no tucupi, tacacá, caruru, vatapá, and maniçoba. The Northeast is known for moqueca (a stew of seafood and palm oil), acarajé (a fritter made with white beans, onion and fried in palm oil (dendê), which is filled with dried shrimp and red pepper), caruru, and Quibebe. In the Southeast, it is common to eat Minas cheese, pizza, tutu, polenta, macaroni, lasagna, and gnocchi. Churrasco is the typical meal of Rio Grande do Sul. Cachaça is Brazil's native liquor, distilled from sugar cane, and it is the main ingredient in the national drink, the caipirinha. Brazil is the world leader in production of green coffee (café).[37] In 2018,[38] 28% of the coffee consumed globally came from Brazil. Because of Brazil's fertile soil, the country has been a major producer of coffee since the times of Brazilian slavery,[39] which created a strong national coffee culture.[40][41][42] This was satirized in the novelty song "The Coffee Song", sung by Frank Sinatra and with lyrics by Bob Hilliard, interpreted as an analysis of the coffee industry,[43][44][45] and of the Brazilian economy and culture.[46][47][48][49]

Literature

Literature in Brazil dates back to the 16th century, to the writings of the first Portuguese explorers in Brazil, such as Pêro Vaz de Caminha, filled with descriptions of fauna, flora and Indigenous peoples that amazed Europeans that arrived in Brazil.[51] When Brazil became a colony of Portugal, there was the "Jesuit Literature", whose main name was father António Vieira, a Portuguese Jesuit who became one of the most celebrated Baroque writers of the Portuguese language. A few more explicitly literary examples survive from this period, José Basílio da Gama's epic poem celebrating the conquest of the Missions by the Portuguese, and the work of Gregório de Matos Guerra, who produced a sizable amount of satirical, religious, and secular poetry. Neoclassicism was widespread in Brazil during the mid-18th century, following the Italian style.

Brazil produced significant works in Romanticism – novelists like Joaquim Manuel de Macedo and José de Alencar wrote novels about love and pain. Alencar, in his long career, also treated Indigenous people as heroes in the Indigenist novels O Guarany, Iracema, Ubirajara.[52] The French Mal du siècle was also introduced in Brazil by the likes of Alvares de Azevedo, whose Lira dos Vinte Anos and Noite na Taverna are national symbols of the Ultra-romanticism. Gonçalves Dias, considered one of the national poets,[53] sang the Brazilian people and the Brazilian land on the famous Song of the Exile (1843), known to every Brazilian schoolchild.[53] Also dates from this period, although his work has hatched in Realism, Machado de Assis, whose works include Helena, Memórias Póstumas de Brás Cubas, O alienista, Dom Casmurro, and who is widely regarded as the most important writer of Brazilian literature.[54][55] Assis is also highly respected around the world.[56][57]

Monteiro Lobato, of the Pré-Modernism (an essentially Brazilian literary movement),[59] wrote mainly for children, often bringing Greek mythology and didacticism with Brazilian folklore, as we see in his short stories about Saci Pererê.[60] Some authors of this time, like Lima Barreto and Simões Lopes Neto and Olavo Bilac, already show a distinctly modern character; Augusto dos Anjos, whose works combine Symbolistic, Parnasian and even pre-modernist elements has a "paralytic language".[61] Mário de Andrade and Oswald de Andrade, from Modernism, combined nationalist tendencies with an interest in European modernism and created the Modern Art Week of 1922. João Cabral de Melo Neto and Carlos Drummond de Andrade are placed among the greatest Brazilian poets;[62] the first, post-modernist, concerned with the aesthetics and created a concise and elliptical and lean poetic, against sentimentality;[63] Drummond, in turn, was a supporter of "anti-poetic" where the language was born with the poem.[64] In Post-Modernism, João Guimarães Rosa wrote the novel Grande Sertão: Veredas, about the Brazilian outback,[65] with a highly original style and almost a grammar of his own,[66] while Clarice Lispector wrote with an introspective and psychological probing of her characters.[67] Vinicius de Moraes, nicknamed "O Poetinha," was notable as a poet, essayist, and lyricist often collaborating with Tom Jobim.[68] Nowadays, Nelson Rodrigues, Rubem Fonseca and Sérgio Sant'Anna, next to Nélida Piñon and Lygia Fagundes Telles, both members of Academia Brasileira de Letras, are important authors who write about contemporary issues sometimes with erotic or political tones. Ferreira Gullar and Manoel de Barros are two highly admired poets and the former has also been nominated for the Nobel Prize.[69]

Visual arts

Painting and sculpture

The oldest known examples of Brazilian art are cave paintings in Serra da Capivara National Park in the state of Piauí, dating back to c. 13,000 BC.[70] In Minas Gerais and Goiás have been found more recent examples showing geometric patterns and animal forms.[71] One of the most sophisticated kinds of Pre-Columbian artifact found in Brazil is the sophisticated Marajoara pottery (c. 800–1400 AD), from cultures flourishing on Marajó Island and around the region of Santarém, and statuettes and cult objects, such as the small carved-stone amulets called muiraquitãs, also belong to these cultures.[72] Many of the Jesuits worked in Brazil under the influence of the Baroque, the dominant style in Brazil until the early 19th century.[73][74] The Baroque in Brazil flourished in Bahia and Pernambuco and Minas Gerais, generating valuable artists like Manuel da Costa Ataíde and especially the sculptor-architect Aleijadinho.[74]

In 1816, the French Artistic Mission in Brazil created the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts and imposed a new concept of artistic education and was the basis for a revolution in Brazilian painting, sculpture, architecture, graphic arts, and crafts.[75] A few decades later, under the personal patronage of Emperor Dom Pedro II, who was engaged in an ambitious national project of modernization, the Academy reached its golden age, fostering the emergence of the first generation of Romantic painters, whence Victor Meirelles and Pedro Américo, that, among others, produced lasting visual symbols of national identity. It must be said that in Brazil Romanticism in painting took a peculiar shape, not showing the overwhelming dramaticism, fantasy, violence, or interest in death and the bizarre commonly seen in the European version, and because of its academic and palatial nature all excesses were eschewed.[76][77][78]

The beginning of the 20th century saw a struggle between old schools and modernist trends. Important modern artists Anita Malfatti and Tarsila do Amaral were both early pioneers in modern art in the country,[79] and are amongst the better known figures of the Anthropophagic Movement, whose goal was to "swallow" modernity from Europe and the US and "digest" it into a genuinely Brazilian modernity. Both participated of The Week of Modern Art festival, held in São Paulo in 1922, that renewed the artistic and cultural environment of the city[80] and also presented artists such as Emiliano Di Cavalcanti, Vicente do Rego Monteiro, and Victor Brecheret.[81] Based on Brazilian folklore, many artists have committed themselves to mix it with the proposals of the European Expressionism, Cubism, and Surrealism. From Surrealism, arises Ismael Nery, concerned with metaphysical subjects where their pictures appear on imaginary scenarios and averse to any recognizable reference.[82] In the next generation, the modernist ideas of the Week of Modern Art have affected a moderate modernism that could enjoy the freedom of the strict academic agenda, with more features conventional method, best exemplified by the artist Candido Portinari, which was the official artist of the government in mid-century.[74]

In recent years, names such as Oscar Araripe, Beatriz Milhazes and Romero Britto have been well acclaimed.

Architecture

Brazilian architecture in the colonial period was heavily influenced by the Portuguese Manueline style, albeit adapted for the tropical climate. A UNESCO World Heritage Site, the city of Ouro Preto in the state of Minas Gerais contains numerous well-preserved examples of this style by artists such as Aleijadinho.[83]

In later centuries, Brazilian architects were increasingly influenced by schools from other countries such as France and the United States, eventually developing a style of their own that has become known around the world. Architects such as Oscar Niemeyer have received much acclaim, with the Brazilian capital Brasília being the most notable example of modern Brazilian architecture.[84] Niemeyer received the Pritzker Architecture Prize in 1988, and in 2006 the prize was awarded to Brazilian architect Paulo Mendes da Rocha.

In recent decades, Brazilian landscape architecture has also attracted some attention, particularly in the person of Roberto Burle Marx. Some of this notable works are the Copacabana promenade in Rio de Janeiro and the Ibirapuera Park in São Paulo.[85]

Photography

Chichico Alkmim was a pioneer of photography in rural Minas Gerais in the early 20th century.[86] Hildegard Rosenthal was a pioneering photojournalist in São Paulo whose photographs from the 1940s have been widely exhibited and published. Sebastião Salgado is an award-winning black and white photographer, known for Genesis and the documentary about his life, The Salt of the Earth.[87] Vik Muniz photographs his art made of unconventional materials, such as peanut butter and jelly.[88] Cássio Vasconcellos, Miguel Rio Branco, and Claudia Andujar are associated photojournalism, associated with aerial photography, social criticism, and anthropology, respectively.

Cinema and theater

Cinema

Cinema has a long tradition in Brazil, reaching back to the birth of the medium in the late 19th century, and gained a new level of international acclaim in recent years.[90] Limite, written and directed by Mário Peixoto, was an avant-garde silent film first screened in 1931.[91] Cinema Novo, embodied by films such as Vidas secas and Deus e o Diabo na Terra do Sol ("Black God, White Devil"), was a film genre and movement in the 1960s and 1970s that emphasized social equality and intellectualism.[92]

The documentary film Bus 174 (2002), by José Padilha, about a bus hijacking, is the highest rated foreign film at Rotten Tomatoes.[93] O Pagador de Promessas (1962), directed by Anselmo Duarte, won the Palme d'Or at the 1962 Cannes Film Festival, the only Brazilian film to date to win the award.[94] Fernando Meirelles' City of God (2002), is the highest rated Brazilian film on the IMDb Top 250 list and was selected by Time magazine as one of the 100 best films of all-time in 2005.[95][96] The highest-grossing film in Brazilian cinema, taking 12 million viewers to cinemas, is Dona Flor and Her Two Husbands (1976), directed by Bruno Barreto and based on the novel of the same name by Jorge Amado.[97][98][99] Acclaimed Brazilian filmmakers include Glauber Rocha, Fernando Meirelles, José Padilha, Anselmo Duarte, Walter Salles, Eduardo Coutinho and Alberto Cavalcanti.

Theater

Theater was introduced by the Jesuits during the colonization, particularly by Father Joseph of Anchieta, but did not attract much interest until the transfer of the Portuguese Court to Brazil in 1808. Over the course of the 18th century, theatre evolved alongside the blossoming literature traditions with names such as Martins Pena and Gonçalves Dias. Pena introduced the comedy of manners, which would become a distinct mark of Brazilian theatre over the next decades.[100]

Theatre was not included in the 1922 Modern Art Week of São Paulo, which marked the beginning of Brazilian Modernism. Instead, in the following decade, Oswald de Andrade wrote O Rei da Vela, which would become the manifesto of the Tropicalismo movement in the 1960s, a time where many playwrights used theatre as a means of opposing the Brazilian military government such as Gianfrancesco Guarnieri, Augusto Boal, Dias Gomes, Oduvaldo Vianna Filho and Plínio Marcos. With the return of democracy and the end of censorship in the 1980s, theatre would again grow in themes and styles. Contemporary names include Gerald Thomas, Ulysses Cruz, Aderbal Freire-Filho, Eduardo Tolentinho de Araújo, Cacá Rosset, Gabriel Villela, Márcio Vianna, Moacyr Góes and Antônio Araújo.[101]

Music

Music is one of the most instantly recognizable elements of Brazilian culture. Many different genres and styles have emerged in Brazil, such as samba, choro, bossa nova, MPB, frevo, forró, maracatu, sertanejo, brega and axé.

Samba

Samba is among the most popular music genres in Brazil and is widely regarded as the country's national musical style. It developed from the mixture of European and African music, brought by slaves in the colonial period and originated in the state of Bahia.[102] In the early 20th century, modern samba emerged and was popularized in Rio de Janeiro behind composers such as Noel Rosa, Cartola and Nelson Cavaquinho among others. The movement later spread and gained notoriety in other regions, particularly in Bahia and São Paulo. Contemporary artists include Martinho da Vila, Zeca Pagodinho and Paulinho da Viola.[103]

Samba makes use of a distinct set of instruments, among the most notable are the cuíca, a friction drum that creates a high-pitched squeaky sound, the cavaquinho, a small instrument of the guitar family, and the pandeiro, a hand frame drum. Other instruments are the surdos, agogôs, chocalhos and tamborins.[104]

Choro

Choro originated in the 19th century through interpretations of European genres such as polka and schottische by Brazilian artists who had already been influenced by African rhythms such as the batuque.[105] It is a largely instrumental genre that shares a number of characteristics with samba. Choro gained popularity around the start of the 20th century (1880-1920) and was the genre of many of the first Brazilian records in the first decades of the 20th century. Notable Choro musicians of that era include Chiquinha Gonzaga, Pixinguinha and Joaquim Callado. The popularity of choro steadily waned after the popularization of samba but saw a revival in recent decades and remains appreciated by a large number of Brazilians.[106] There are a number of acclaimed Choro artists nowadays such as Altamiro Carrilho, Yamandu Costa and Paulo Bellinati.

Bossa nova and MPB

Bossa nova is a style of Brazilian music that originated in the late 1950s.[107] It has its roots on samba but features less percussion, employing instead a distinctive and percussive guitar pattern. Bossa nova gained mainstream popularity in Brazil in 1958 with the song Chega de Saudade, written by Antônio Carlos Jobim and Vinícius de Moraes. Together with João Gilberto, Jobim and Moraes would become the driving force of the genre, which gained worldwide popularity with the song "Garota de Ipanema" as interpreted by Gilberto, his wife Astrud and Stan Getz on the album Getz/Gilberto.[108] The bossa nova genre remains popular in Brazil, particularly among the upper classes and in the Southeast.

MPB (acronym for Música popular brasileira, or Brazilian Popular Music) was a trend in Brazilian music that emerged after the bossa nova boom. It presents many variations and includes elements of styles that range from Samba to Rock music.[109]

Tropicalismo

In the 1960s some MPB artists founded the short-lived but highly influential Tropicália or Tropicalismo movement, which attracted international attention. Among those were Caetano Veloso, Gilberto Gil, Jorge Mautner,[110] Tom Zé, Nara Leão, Ney Matogrosso and Os Mutantes.[111] Although the movement was rooted in music, it also found expression in film, theater, poetry, and politics.[110]

Sertanejo

Sertanejo is the most popular genre in Brazilian mainstream media since the 1990s. It evolved from música caipira over the course of the 20th century,[112] a style of music that originated in Brazilian countryside and that made use of the viola caipira, although it presents nowadays a heavy influence from American country music but resembles in many ways including writing style with Pimba Music of Portugal. Beginning in the 1980s, Brazil saw an intense massification of the sertanejo genre in mainstream media and an increased interest by the phonographic industry.[113] As a result, sertanejo is today the most popular music genre in Brazil in terms of radio play. Common instruments in contemporary sertanejo are the acoustic guitar, which often replaces the viola, the accordion and the harmonica, as well as electric guitar, bass and drums.[114] Traditional acts include Chitãozinho & Xororó, Zezé Di Camargo & Luciano, Leonardo and Daniel. Newer artists such as Michel Teló, Luan Santana, Gusttavo Lima have also become very popular recently among younger audiences.

Forró and frevo

Forró and Frevo are two music and dance forms originated in the Brazilian Northeast. Forró, like Choro, originated from European folk genres such as the schottische in between the 19th and early 20th centuries. It remains a very popular music style, particularly in the Northeast region, and is danced in forrobodós (parties and balls) throughout the country.[115]

Frevo originated in Recife, Pernambuco during the Carnival, the period it is most often associated with. While the music presents elements of procession and martial marches, the frevo dance (known as "passo") has been notably influenced by capoeira.[116] Frevo parades are a key tradition of the Pernambuco Carnival.

Classical music

Brazil has also a tradition in the classical music, since the 18th Century. The oldest composer with the full documented work is José Maurício Nunes Garcia, a Catholic priest who wrote numerous pieces, both sacred and secular, with a style resembling the classical viennese style from Mozart and Haydn. In the 19th Century, the composer Antonio Carlos Gomes wrote several operas with Brazilian indigenous themes, with librettos in Italian, some of which premiered in Milan; two of the works are the operas Il Guarany and Lo Schiavo (The Slave).

In the 20th Century, Brazil had a strong modernist and nationalist movement, with the works of internationally renowned composers like Heitor Villa-Lobos, Camargo Guarnieri, César Guerra-Peixe and Cláudio Santoro, and more recently Marlos Nobre and Osvaldo Lacerda. Many famous performers are also from Brazil, such as the opera singer Bidu Sayão, the pianist Nelson Freire and the former pianist and now conductor João Carlos Martins.

The city of São Paulo hosts the Sala São Paulo, home of the São Paulo State Symphony Orchestra (OSESP), one of the most outstanding concert halls of the world. Also the city of Campos do Jordão hosts yearly in June the Classical Winter Festival, with performances of many instrumentists and singers from all the world.

Other genres

Many other genres have originated in Brazil, specially in recent years. Some of the most notable are:

- The mangue beat movement, originated in Recife and founded by the late Chico Science and Nação Zumbi. The music fuses elements of maracatu, frevo, funk rock and hip hop.[117]

- Axé is a very popular genre, particularly in the state of Bahia. It is a fusion of Afro-Caribbean rhythms and is strongly associated with the Salvador Carnival.[118]

- Maracatu is another genre originated in the state of Pernambuco. It evolved from traditions passed by generations of African slaves and features large percussive groups and choirs.[119]

- Brega which literally means 'Tacky' is a hard to define music style from the state of Pará, usually characterized as influenced by Caribbean rhythms and containing simple rhymes, arrangements and a strong sentimental appeal. It has spawned subgenres such as tecno brega, which has attracted worldwide interest for achieving high popularity without significant support from the phonographic industry.[120]

Dances

Popular culture

Television

Television has played a large role in the formation of the contemporary Brazilian popular culture. It was introduced in 1950 by Assis Chateaubriand and remains the country's most important element of mass media.

Telenovelas are a marking feature in Brazilian television, usually being broadcast in prime time on most major television networks. Telenovelas are similar in concept to soap operas in English-speaking countries but differ from them in duration, telenovelas being significantly shorter (usually about 100 to 200 episodes). They are widely watched throughout the country, to the point that they have been described as a significant element in national identity and unity, and have been exported to over 120 countries.[121]

Folklore

Brazilian folklore includes many stories, legends, dances, superstitions and religious rituals. Characters include the Boitatá, the Boto Cor-de-Rosa, the Saci and the Bumba Meu Boi, which has spawned the famous June festival in Northern and Northeastern Brazil.[122]

Social Media

Social media in Brazil is the use of social networking applications in this South American nation. This is due to economic growth and the increasing availability of computers and smartphones. Brazil is the world's second-largest user of Twitter (at 41.2 million tweeters), and largest market for YouTube outside the United States.[123] In 2012, average time spent on Facebook increased 208% while global use declined by 2%.[123] In 2013, Brazil ranked the second highest number of Facebook users globally at 65 million.[123] During this period, social media users in Brazil spent on average 9.7 hours a month online.[123]

Sports

Football is the most popular sport in Brazil.[32] Many Brazilian players such as Pelé, Ronaldo, Kaká, Ronaldinho, and Neymar are among the most well known players in the sport. The Brazil national football team (Seleção) is currently among the best in the world, according to the FIFA World Rankings. They have been victorious in the FIFA World Cup a record 5 times, in 1958, 1962, 1970, 1994, and 2002.[124] Basketball, volleyball, auto racing, and martial arts also attract large audiences. Tennis, handball, swimming, and gymnastics have found a growing sporting number of enthusiasts over the last decade. Some sport variations have their origins in Brazil. Beach football,[125] futsal (official version of indoor football),[126] and footvolley emerged in the country as variations of football. In martial arts, Brazilians have developed capoeira,[127] vale tudo,[128] and Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu.[129] In auto racing, Brazilian drivers have won the Formula One World Championship 8 times: Emerson Fittipaldi in 1972 and 1974;[130] Nelson Piquet in 1981, 1983, and 1987;[131] and Ayrton Senna in 1988, 1990, and 1991.[132]

Brazil has undertaken the organization of large-scale sporting events: the country organized and hosted the 1950 FIFA World Cup,[133] and the 2014 FIFA World Cup event.[134] The circuit located in São Paulo, called Autódromo José Carlos Pace, hosts the annual Grand Prix of Brazil.[135] São Paulo organized the IV Pan American Games in 1963,[136] and Rio de Janeiro hosted the XV Pan American Games in 2007.[136] Brazil also tried for the 4th time to host the Summer Olympics with Rio de Janeiro candidature in 2016.[137] On October 2, 2009, Rio de Janeiro was selected to host the 2016 Summer Olympics, which was the first held in South America.[138]

Family and social class

As a society with strong traditional values, the family in Brazil is usually represented by the couple and their children. Extended family is also an important aspect with strong ties being often maintained.[139] Accompanying a world trend, the structure of the Brazilian family has seen major changes over the past few decades with the reduction of average size and increase in single-parent, dual-worker and remarried families. The family structure has become less patriarchal and women are more independent, although gender disparity is still evident in wage difference.[140]

Brazil inherited a highly traditional and stratified class structure from its colonial period with deep inequality. In recent decades, the emergence of a large middle class has contributed to increase social mobility and alleviate income disparity, but the situation remains grave. Brazil ranks 54th among world countries by Gini index.[141]

According to the anthropologist Alvaro Jarrin, "The body is a key aspect of sociability in Brazilian society because it communicates a person's social standing. Those with the resources and time to become beautiful will undoubtedly do so. Members of the upper-middle class use the phrase 'gente bonita' or 'beautiful people' as a euphemism for the people with whom they consider it appropriate to associate oneself with. An up-and-coming locale, for instance, is not valued by its price of admission or its fare, but rather by the amount of 'gente bonita' who frequent it. The imbrication of race and class in Brazil produces this upper-middle class as normatively white, excluding a majority of the Brazilian population from beauty. Afro-textured hair is portrayed as 'bad hair', and a nose considered wider and non-European is also described as a 'poor person's nose'. The physical features that are aesthetically undesirable mark certain bodies as inferior in the relatively rigid Brazilian social pyramid, undeserving of social recognition and full citizenship within the nation... Since the body is considered to be infinitely malleable, a person who climbs the social ladder is expected to transform their body to conform to upper-middle class standards. The working class is willing to spend on beauty not as a form of conspicuous consumption, but rather because it perceives beauty as an essential requirement for social inclusion." [142]

Social Customs

In Brazilian culture, living in a community is vital due to the fact Brazilians are very involved with one another. “Brazilians organize their lives around and about others, maintain a high level of social involvement, and consider personal relations of primary importance in all human interactions. In fact, being with others is so important that they are rarely alone and perceive the desire to be alone as a sign of depression or unhappiness.”[143] Due to the fact Brazilians are highly involved with social life, many friends, family members, or business partners join together to associate.

Although friend and family relationships have a large impact on Brazilian culture, business relationships are also crucial. “As Brazilians depend heavily on relationships with others, it is essential to spend time getting to know, both personally and professionally, your Brazilian counterparts. One of the most important elements in Brazilian business culture is personal relationships.”[144] Brazilians maintain a comfortable business atmosphere by being respectful and using the correct greeting.

Upon greeting, Brazilians often express themselves physically. Women usually kiss the other individual on both cheeks and men usually give a pat on the back. Friendly gestures are used to greet one another. It is common for them to refer to the individual's social standing and then their first name when engaging in conversation. When Brazilians speak with an individual older than them, they address them as “senhor” (Mister) or “senhora” (Miss), accompanied by the individual's first name. In Brazil, the general rule is to use a formal greeting when communicating with people who are unfamiliar or older.[145]

Beauty

According to the anthropologist Alvaro Jarrin, "Beauty is constantly lived, breathed and incorporated as a social category in southeastern Brazil. The talk of beauty is pervasive in all kinds of media, from television to song lyrics, and it is a daily concern of people of all incomes and backgrounds. Remarking about a person's appearance is not only socially permissible, it is equivalent to inquiring about that person's health and showing concern for them. If a person does not look his or her best, then many Brazilians assume the person must be sick or going through emotional distress." [142] Vanity does not carry a negative connotation, as it does in many other places. The average weight of a Brazilian woman is 62 kilos (137 lbs),[146] as opposed to 75 kilos (166 lbs) in the United States[147] and 68 kilos (152 lbs) in the United Kingdom.[148]

Brazil has more plastic surgeons per capita than anywhere else in the world.[149] In 2001, there were 350,000 cosmetic surgery operations in a population of 170 million.[150] This is an impressive number for a nation where sixty percent of the working population earns less than 150 U.S. dollars per month.[151] In 2007 alone, Brazilians spent US$22 billion on hygiene and cosmetic products making the country the third largest consumer of cosmetic products in the world.[150] 95% of Brazilian women want to change their bodies and the majority will seriously consider going under the knife. The pursuit of beauty is so high on the agenda for Brazilian women that new research shows they spend 11 times more of their annual income on beauty products (compared to UK and US women).[152] Brazil has recently emerged as one of the leading global destinations for medical tourism. Brazilians are no strangers to cosmetic surgery, undergoing hundreds of thousands of procedures a year, by all socio-economic levels as well.[153]

The general attitude in Brazil toward cosmetic surgery borders on reverence. Expressions such as "the power of the scalpels," "the magic of cosmetic surgeries," and the "march toward scientific progress" are seen and heard everywhere. Whereas cosmetic surgery in the U.S. or Europe is still seen as a private matter, and one that is slightly embarrassing or at least socially awkward, in Brazil surgeries are very public matters. To have plastic surgery is to show that you have the money to afford it. In Brazil, modifying one's body through surgery is about more than just becoming more beautiful and desirable. It is even about more than showing that you care about yourself, which is a phrase in the Brazilian mass media. Surgical transformations are naturalized as necessary enhancements. Instead, modifying your body in Brazil is fundamentally about displaying your wealth. But since much is associated with race, changing one's body is also about approximating whiteness.[154] An April 2013 article in The Economist noted that "[looking white] still codes for health, wealth and status. Light-skinned women strut São Paulo's upmarket shopping malls in designer clothes; dark-skinned maids in uniform walk behind with the bags and babies. Black and mixed-race Brazilians earn three-fifths as much as white ones. They are twice as likely to be illiterate or in prison, and less than half as likely to go to university. ... The unthinking prejudice expressed in common phrases such as 'good appearance' (meaning pale-skinned) and 'good hair' (not frizzy) means many light-skinned Brazilians have long preferred to think of themselves as 'white', whatever their parentage."[155]

There are marking differences between perceptions of beauty among working-class patients in public hospitals, and upper-middle class patients in private clinics. Plastic surgery is conceptualized by the upper-middle class mainly as an act of consumption that fosters distinction and reinforces the value of whiteness. In contrast, working-class patients describe plastic surgery as a basic necessity that provides the "good appearance" needed in the job market and "repairs" their bodies from the wear of their physical labor as workers and as mothers. Patients from different walks of life desire plastic surgery for different reasons.

The idea that physical appearance can denote class, with the implication that modifications in one's physical appearance can be seen as markers of social status extends throughout Brazil. Put within a context of explicit social inequality, the link between the production of beauty and social class becomes quite evident. Brazilians place a heavy importance in beauty aesthetics; a study in 2007 revealed that 87% of all Brazilians seek to look stylish at all times, opposed to the global average of 47%.[156] The body is understood in southeastern Brazil as having a crucial aesthetic value, a value that is never fixed but can be accrued through discipline and medical intervention. This 'investment' on the body is nearly always equated with health, because a person's well-being is assumed to be visible on the surface of their body. One of the most common (and harshest) expressions about beauty in Brazil is "there are really no ugly people, there are only poor people."[157]

Holidays

| Date | English name | Portuguese name | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| January 1 | New Year's Day | Ano Novo/ Confraternização Universal | Celebrates the beginning of the Gregorian calendar year. Festivities include counting down to midnight on the preceding night. Traditional end of the holiday season. |

| March/April (Variable) | Good Friday | Sexta-feira Santa | Christian holiday, celebrates the passion and death of Jesus on the cross. |

| April 21 | Tiradentes' Day | Dia de Tiradentes | Anniversary of the death of Tiradentes (1792), considered a national martyr for being part of the Inconfidência Mineira, an insurgent movement that aimed to establish an independent Brazilian republic. |

| May 1 | Labor Day | Dia do Trabalhador | Celebrates the achievements of workers and the labor movement. |

| June (Variable) | Corpus Christi | Corpus Christi | A national Catholic holiday which celebrates the Eucharist and the belief of the real presence of Jesus in the host. |

| September 7 | Independence Day | Dia da Independência or 7 de Setembro | Celebrates the Declaration of Independence from Portugal on September 7, 1822. |

| First and last Sunday in October | Election Day | Dia da Eleição or Eleições | In every 2 years, Brazilians have the obligation to vote. The first election round always happens on the first Sunday in October; if there necessary a second-round, this will happen on the last Sunday in the same October. |

| October 12 | Our Lady of Aparecida' Day | Dia de Nossa Senhora Aparecida | Commemorates the Virgin Mary as Nossa Senhora da Conceição Aparecida, Patron Saint of Brazil. Also celebrated as Children's Day (Dia das Crianças) on the same date. |

| November 2 | All Soul's Day | Dia de Finados | Another Christian holiday, it commemorates the faithful departed. |

| November 15 | Republic Day | Proclamação da República | Commemorates the end of the Empire of Brazil and the proclamation of the Brazilian Republic on November 15, 1889. |

| December 25 | Christmas Day | Natal | Celebrates the nativity of Jesus. |

References

- Teresa A. Meade (2009). A Brief History of Brazil. Infobase Publishing. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-8160-7788-5.

- "BRASIL CULTURA | O site da cultura brasileira". Archived from the original on April 5, 2009.

- "15th-16th Century". History. Brazilian Government official website. Archived from the original on 2007-06-15. Retrieved 2008-06-08.

- "People and Society". Encarta. MSN. Archived from the original on 2009-10-31. Retrieved 2008-06-10.

- "Population". Encarta. MSN. Archived from the original on 2009-10-31. Retrieved 2008-06-10.

- Freyre, Gilberto (1986). "The Afro-Brazilian experiment – African influence on Brazilian culture". UNESCO. Retrieved 2008-06-08.

- "The Culture of Brazil". Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- "IBGE teen". 24 February 2013. Archived from the original on 24 February 2013.

- "IBGE teen". 15 March 2008. Archived from the original on 15 March 2008.

- "IBGE teen". 15 March 2008. Archived from the original on 15 March 2008.

- "IBGE Educa". IBGE - Educa. Archived from the original on November 12, 2007.

- "IBGE Educa". IBGE - Educa. Archived from the original on October 29, 2007.

- "Modern Art Week and the Rise of Brazilian Modernism | Brazil: Five Centuries of Change". library.brown.edu. Retrieved 2020-07-12.

- "Tarsila do Amaral: Inventing Modern Art in Brazil | MoMA". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 2020-07-12.

- Maciel, Fabrício (2020-06-23). O Brasil-nação como ideologia: a construção retórica e sociopolítica da identidade nacional (in Portuguese). Editora Autografia. ISBN 978-65-5531-214-0.

- "Movement – Tropicália". Retrieved 2020-07-12.

- Dunn, Christopher (2005). "Tropicália". Oxford African American Studies Center. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195301731.013.43672. ISBN 9780195301731. Retrieved 2020-07-12.

- "A guide to Brazil – etiquette, customs, clothing and more…". Kwintessential.

- Naro & Scherre (2007)

- Naro, Anthony Julius; Scherre, Maria Marta Pereira (January 1, 2007). Origens do português brasileiro. Parábola. ISBN 9788588456655 – via Google Books.

- Noll, Volker, "Das Brasilianische Portugiesisch", 1999.

- "o portugues brasileiro: formaçao e contrastes - Livro". m.travessa.com.br.

- "Miscigenação da Língua Portuguesa". Brasil Escola.

- "O alemão lusitano do Sul do Brasil". DW-World.de.

- "ELB". www.labeurb.unicamp.br.

- "The New Seven Wonders of the World". Hindustan Times. July 8, 2007. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved July 11, 2007.

- "Basílica de Aparecida aguarda 160 mil pessoas". Terra.

- "Jesuítas". Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- "Censo". Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- "2010 Population Census - General characteristics of population, religion and persons with disabilities (Portuguese)". ibge.gov.br (in Portuguese). 2012-11-16. Archived from the original on 2012-11-16. Retrieved 2019-08-10.CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

- "Carnival in Brazil - TOPICS Online Magazine". www.topics-mag.com.

- "Way of Life". Encarta. MSN. Archived from the original on 2009-10-31. Retrieved 2008-06-08.

- (in English) "As origens da Feijoada: O mais brasileiro dos sabores Archived 2009-02-28 at the Wayback Machine", by João Luís de Almeida Machado. Visited on November 8, 2009.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-11-29. Retrieved 2009-11-08.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Brazil National Dish: Feijoada Recipe and Restaurants". brazilmax.com. 2010-11-20. Archived from the original on 2010-11-20. Retrieved 2019-08-10.

- CASCUDO, Luís da Câmara. História da Alimentação no Brasil – 2 vols. 2ª ed. Itatitaia, Rio de Janeiro, 1983.

- "International Coffee Organization". Archived from the original on July 6, 2010.

- nationalcoffee (29 January 2019). "Boom Time for the Brazilian Coffee Industry".

- "Sabor do Café/História do café Archived March 5, 2010, at the Wayback Machine". Visited on November 8, 2009.

- Impacto, Antonio Sergio Souza, Agência; Cafeicultura, Revista. "Café brasileiro mundo afora". Revista Cafeicultura.

- Museu do Café. Café no Brasil. Visited on November 8, 2009.

- Gislane e Reinaldo. História (Textbook). Editora Ática, 2009, p. 352

- "There's an awful lot of coffee in – Vietnam". Retrieved 2008-07-21.

- "An Awful Lot of Coffee in the Bin". Time Magazine. September 1967. Retrieved 2008-07-21.

- Philip Hoplins (July 2003). "More home-grown beans in the daily grind". The Age. Retrieved 2008-07-21.

- There's an Awful Lot of Bubbly in Brazil: The Life and Times of a Bon Viveur: Amazon.co.uk: Alan Brazil, Mike Parry: 9781905156368: Books. ASIN 1905156367.

- "FindArticles.com - CBSi". findarticles.com.

- Caulkin, Simon (5 February 2006). "There's an awful lot of motivation in Brazil" – via www.theguardian.com.

- Rohter, Larry (12 June 2001). "San Alberto Journal; Local Cry: An Awful Lot of Brazilians in Paraguay" – via NYTimes.com.

- Candido; Antonio. (1970) Vários escritos. São Paulo: Duas Cidades. p.18

- "Literature". Encarta. MSN. Archived from the original on 2009-10-31. Retrieved 2008-06-08.

- "Brazilian Literature: An Introduction Archived July 25, 2011, at the Wayback Machine". Embassy of Brasil – Ottawa. Visited on November 2, 2009.

- "Antonio Gonçalves Dias". Article on Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Caldwell, Helen (1970) Machado de Assis: The Brazilian Master and his Novels. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London, University of California Press.

- Fernandez, Oscar Machado de Assis: The Brazilian Master and His Novels The Modern Language Journal, Vol. 55, No. 4 (Apr., 1971), pp. 255–256

- João Cezar de Castro Rocha, "Introduction" Archived June 25, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. Portuguese Literature and Cultural Studies 13/14 (2006): xxiv.

- Bloom, Harold (2002). Genius: A Mosaic of One Hundred Exemplary Creative Minds. New York: Warner Books. p. 674. ISBN 978-0-446-52717-0. OCLC 49031283.

- Gonçalves Dias. Song of the Exile. Translated by John Milton and disponible on The NeoConcrete Movement Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Page visited on November 3, 2009.

- (in Portuguese) E-Dicionário de literatura Archived December 19, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Visited on April 4, 2008.

- (in Portuguese) Unnamed. "José Bento Monteiro Lobato reconta a Mitologia Grega Archived March 4, 2010, at the Wayback Machine", in: Recanto das Letras. Visited on May 13, 2009.

- Anjos, Augusto. A Idéia

- The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition Copyright. 2004, Columbia University Press. Licensed from Lernout & Hauspie Speech Products N.V.

- (in Portuguese) Terra, Ernani. De Nicola, José. Português: de olho no mundo do trabalho (Textbook), p.523. 3rd edition. Editora Scipione, São Paulo, 2006.

- (in Portuguese) Terra, Ernani. De Nicola, José. Português: de olho no mundo do trabalho (Textbook), p.28

- "Grande sertão: veredas - parte I". educaterra.terra.com.br (in Portuguese). 2005-04-13. Archived from the original on 2005-04-13. Retrieved 2019-08-10.

- (in Portuguese) Terra, Ernani. De Nicola, José. Português: de olho no mundo do trabalho (Textbook), p.516.

- (in Portuguese) Terra, Ernani. De Nicola, José. Português: de olho no mundo do trabalho (Textbook), p.517

- "Vinícius de Moraes | Brazilian poet and lyricist". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-08-18.

- "Brazilian literature". Portuguese Culture. Retrieved 2019-08-10.

- Almanaque Abril 2007. São Paulo: Editora Abril, 2007, p. 234.

- "Martins, Simone B. & Imbroisi, Margaret H. História da Arte, 1988". Archived from the original on October 31, 2010.

- Correa, Conceição Gentil. Estatuetas de cerâmica na cultura Santarém. Belém: Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, 1965.

- KARNAL, Leandro. Teatro da Fé: Formas de Representação Religiosa no Brasil e no México do Século XVI. São Paulo, Editora Hucitec, 1998. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-07-24. Retrieved 2010-10-25.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Cultural, Instituto Itaú. "Enciclopédia Itaú Cultural". Enciclopédia Itaú Cultural.

- CONDURU, Roberto. Araras Gregas. In: 19&20 – A revista eletrônica de DezenoveVinte. Volume III, n. 2, abril de 2008

- BISCARDI, Afrânio & ROCHA, Frederico Almeida. O Mecenato Artístico de D. Pedro II e o Projeto Imperial. In: 19&20 – A revista eletrônica de DezenoveVinte. Volume I, n. 1, maio de 2006

- CARDOSO, Rafael. A Academia Imperial de Belas Artes e o Ensino Técnico. In: 19&20 – A revista eletrônica de DezenoveVinte. Volume III, n. 1, janeiro de 2008

- FERNANDES, Cybele V. F. A construção simbólica da nação: A pintura e a escultura nas Exposições Gerais da Academia Imperial das Belas Artes. In: 19&20 – A revista eletrônica de DezenoveVinte. Volume II, n. 4, outubro de 2007

- "Art and Architecture". Encarta. MSN. Archived from the original on 2009-10-31. Retrieved 2008-06-08.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-09-25. Retrieved 2010-08-26.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Semana da Arte Moderna. Pitoresco Website". Archived from the original on April 14, 2010.

- (in English) "Ismael Nery: Critical Commentary Archived March 11, 2012, at the Wayback Machine". On Itaú Cultural Visual Artes. Visited on November 8, 2009.

- "BRAZIL - Arquitetura". Archived from the original on 28 May 2011. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- "BRAZIL - Arquitetura". Archived from the original on 2011-05-28.

- Rohter, Larry (2009-01-21). "A New Look at the Landscaping Artist Roberto Burle Marx". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- "Exposição Chichico Alkmim". fcs.mg.gov.br (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2020-08-18.

- Rohter, Larry (23 March 2015). "Sebastião Salgado's Journey From Brazil to the World". The New York Times.

- Kino, Carol (2010-10-21). "Where Art Meets Trash and Transforms Life". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-08-18.

- Braga, Gabriel Ferreira (2011). "Entre o fanatismo e a utopia: trajetória de antônio conselheiro e do beato zé lourenço na literatura de cordel". Biblioteca Digital de Teses e Dissertações da UFMG. Retrieved 2019-08-10.

- "Theater and Film". Encarta. MSN. Archived from the original on 2009-10-31. Retrieved 2008-06-08.

- "Limite". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved 2020-12-21.

- Dennison, Stephanie; Shaw, Lisa (2004-11-27). Popular Cinema in Brazil: 1930-2001. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-6499-9.

- Best of Foreign at Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2009-10-27

- "Festival de Cannes: O Pagador de Promessas". festival-cannes.com. Archived from the original on 2011-09-15. Retrieved 2009-02-23.

- "ALL-TIME 100". Time. 2005-02-12.

- Cidade de Deus (2002) at IMDb

- "Revista de Cinema". www2.uol.com.br (in Portuguese). 2008-03-14. Archived from the original on 2008-03-14. Retrieved 2019-08-10.

- "Filmes Nacionais Com Mais De Um Milhão De Espectadores (1970/2007)" (PDF). Agência Nacional do Cinema. Retrieved 2019-08-10.

- "o maior portal sobre o mercado de cinema no Brasil". Filme B (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2019-08-10.

- "Theatre". Archived from the original on 9 July 2011. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- "Theatre". Archived from the original on 9 July 2011. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- "Samba music". Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- "Samba e história do samba". Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- "Samba Instruments". Archived from the original on 10 August 2011. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- "O que é choro?". Archived from the original on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "Confraria de choro". Archived from the original on 6 December 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "A estética da bossa nova". Archived from the original on 10 July 2009. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "Multirio". Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "Brasil 500 anos". Archived from the original on 2001-03-08. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- Mac Cord, Getúlio. (2011). Tropicália : um caldeirão cultural (1. ed.). Rio de Janeiro: Ferreira. ISBN 978-85-7842-179-3. OCLC 741538920.

- "Tripicalism". Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "Música sertaneja". Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- CALDAS, Waldenyr (1979). Acorde na aurora: música sertaneja e a indústria cultural. São Paulo: Ed. Nacional.

- "Sertanejo". Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "Forró in a nutshell". Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "Frevo". Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "Mangue bit". Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "Candomblé sem mistério". Archived from the original on 19 December 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "Maracatu". Archived from the original on 8 February 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "Brega pop". Archived from the original on 4 April 2004. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "Telenovela". Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- "Brazilian folklore". Archived from the original on 20 July 2012. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- Joia, Luiz Antonio. "Social Media and the ‘20 Cents Movement’ in Brazil: What Lessons Can Be Learnt from This?" Information Technology for Development, vol. 22, no. 3, July 2016, pp. 422–435. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1080/02681102.2015.1027882.

- "Football in Brazil". Goal Programme. International Federation of Association Football. 2008-04-15. Retrieved 2008-06-06.

- "Beach Soccer". International Federation of Association Football. Retrieved 2008-06-06.

- "Futsal". International Federation of Association Football. Retrieved 2008-06-06.

- "What is Capoeira?". SCC. 2011-07-09. Archived from the original on 2012-03-26. Retrieved 2011-07-09.

- "Brazilian Vale Tudo". I.V.C. Archived from the original on 1998-05-30. Retrieved 2008-06-06.

- "Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu Official Website". International Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu Federation. Archived from the original on 2008-04-20. Retrieved 2008-06-06.

- Donaldson, Gerald. "Emerson Fittipaldi". Hall of Fame. The Official Formula 1 Website. Retrieved 2008-06-06.

- Donaldson, Gerald. "Nelson Piquet". Hall of Fame. The Official Formula 1 Website. Retrieved 2008-06-06.

- Donaldson, Gerald. "Ayrton Senna". Hall of Fame. The Official Formula 1 Website. Retrieved 2008-06-06.

- "1950 FIFA World Cup Brazil". Previous FIFA World Cups. International Federation of Association Football. Retrieved 2008-06-06.

- "2014 FIFA World Cup Brazil". International Federation of Association Football. Archived from the original on 2008-06-06. Retrieved 2008-06-06.

- "Formula 1 Grande Premio do Brasil 2008". The Official Formula 1 Website. Retrieved 2008-06-06.

- "Chronological list of Pan American Games". Pan American Sports Organization. Archived from the original on August 9, 2013. Retrieved 2008-06-06.

- "Rio de Janeiro 2016 Olympic bid official website". Brazilian Olympic Committee. Archived from the original on 2008-06-07. Retrieved 2008-06-06.

- The Guardian, October 2, 2009, Olympics 2016: Tearful Pele and weeping Lula greet historic win for Rio

- "Brazilian family". Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- "Brazilian family". Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- "Gini index". Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- Alvaro, Jarrín. "Cosmetic Citizenship: Beauty, Affect and Inequality in Southeastern Brazil" (PDF). Department of Cultural Anthropology. Duke University. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- Vincent, Jon (2003). Culture and Customs of Brazil. Westport, Conn : Greenwood. pp. 82. ISBN 9780313304958.

- Véras, Erika Zoeller Daniel Bicudo (2001). "Cultural Differences Between Countries: The Brazilian and the Chinese Ways of Doing Business".

- "Brazilian Culture - Greetings". Cultural Atlas. Retrieved 2019-11-17.

- Do G1, em São Paulo (2010-08-27). "G1 - Metade dos adultos brasileiros está acima do peso, segundo IBGE - notícias em Brasil". G1.globo.com. Retrieved 2012-07-13.

- "Body Measurements". Center for Control of Diseases. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- "The Welsh Health Survey 2009, p. 58" (PDF). Wales.gov.uk. 2010-09-15. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-09-16. Retrieved 2011-01-22.

- "Model is remade for Playboy as Brazil goes under the scapel". The Guardian. 29 November 2000.

- "Corpos a Venda". American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. 2001 Statistics. 6 March 2002.

- Bethell, L. "Politics in Brazil: From Elections without Democracy to Democracy without Citizenship". Daedalus. no. 2 (129): 1–28.

- "Made in Brazil: Why Brazil leads the way with beauty trends". Stylist. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- "Cosmetic Surgery in Brazil". Off2Brazil. Archived from the original on 2013-12-03. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- Kulick, Don (2005). Fat: The Anthropology of an Obsession. New York, New York: Penguin Group. pp. 121–137.

- H.J. (April 26, 2013). "Affirmative action in Brazil: Slavery's legacy". The Economist. London, UK. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- "Beauty and the Buck". Nielsen. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- Machado-Borges, Thaïs (2009). "Producing Beauty in Brazil: Vanity, Visibility and Social Inequality". Vibrant - Virtual Brazilian Anthropology. Brazilian Anthropological Association. 6 (1): 1–30.

.jpg.webp)

_por_Rodrigo_Tetsuo_Argenton.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)