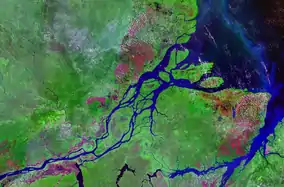

Amazon basin

The Amazon Basin is the part of South America drained by the Amazon River and its tributaries. The Amazon drainage basin covers an area of about 6,300,000 km2 (2,400,000 sq mi), or about 35.5 percent of the South American continent. It is located in the countries of Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, French Guiana (France), Guyana, Peru, Suriname, and Venezuela.[1]

Most of the basin is covered by the Amazon rainforest, also known as Amazonia. With a 5.5 million km2 (2.1 million sq mi) area of dense tropical forest, this is the largest rainforest in the world.

Geography

The Amazon River begins in the Andes Mountains at the west of the basin with its main tributary the Marañón River and Apurimac River in Peru. The highest point in the watershed of the Amazon is the peak of Yerupajá at 6,635 metres (21,768 ft).

With a length of about 6,400 km (4,000 mi) before it drains into the Atlantic Ocean, it is one of the two longest rivers in the world. A team of scientists has claimed that the Amazon is longer than the Nile,[2] but debate about its exact length continues.[3]

The Amazon system transports the largest volume of water of any river system, accounting for about 20% of the total water carried to the oceans by rivers.

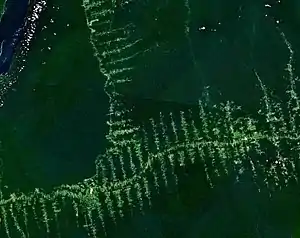

(Some of the Amazon rainforests are deforested because of an increase in cattle ranches and soybean fields.)

The Amazon basin formerly flowed west to the Pacific Ocean until the Andes formed, causing the basin to flow eastward towards the Atlantic Ocean.[4]

Politically the basin is divided into the Peruvian Legal Amazonia, Brazilian Legal Amazônia, the Amazon region of Colombia and parts of Bolivia, Ecuador and the Venezuelan state of Amazonas.

Plant life

Plant growth is dense and its variety of animal inhabitants is comparatively high due to the heavy rainfall and the dense and extensive evergreen and coniferous forests. Little sunlight reaches the ground due to the dense roof canopy by plants. The ground remains dark and damp and only shade-tolerant vegetation will grow here. Orchids and bromeliads exploit trees and other plants to get closer to the sunlight. They grow hanging onto the branches or tree trunks with aerial roots, not as parasites but as epiphytes. Species of tropical trees native to the Amazon include Brazil nut, rubber tree and Assai palm.[5][6]

Wildlife

.jpg.webp)

Mammals

More than 1,400 species of mammals are found in the Amazon, the majority of which are species of bats and rodents. Its larger mammals include the jaguar, ocelot, capybara, puma and South American tapir.

Birds

About 1500 bird species inhabit the Amazon Basin.[7] The biodiversity of the Amazon and the sheer number of diverse bird species is given by the number of different bird families that reside in these humid forests. An example of such would be the cotinga family, to which the Guianan cock-of-the-rock belong. Birds such as toucans, and hummingbirds are also found here. Macaws are famous for duck gathering by the hundreds along the clay cliffs of the Amazon River. In the western Amazon hundreds of macaws and other parrots descend to exposed river banks to consume clay on an almost daily basis,[8] the exception being rainy days.[9]

Reptiles

The green anaconda inhabits the shallow waters of the Amazon and the emerald tree boa and boa constrictor live in the Amazonian tree tops.

Many reptiles species are illegally collected and exported for the international pet trade. Live animals are the fourth largest commodity in the smuggling industry after drugs, diamonds and weapons.[10]

Amphibians

More than 1,500 species of amphibians swim and are found in the Amazon. Unlike temperate frogs which are mostly limited to habitats near the water, tropical frogs are most abundant in the trees and relatively few are found near bodies of water on the forest floor. The reason for this occurrence is quite simple: frogs must always keep their skin moist since almost half of their respiration is carried out through their skin. The high humidity of the rainforest and frequent rainstorms gives tropical frogs infinitely more freedom to move into the trees and escape the many predators of rainforest waters. The differences between temperate and tropical frogs extend beyond their habitat.

.jpg.webp)

Waterlife

About 2,500 fish species are known from the Amazon basin and it is estimated that more than 1,000 additional undescribed species exist.[11] This is more than any other river basin on Earth, and Amazonia is the center of diversity for Neotropical fishes.[12] About 45% (more than 1,000 species) of the known Amazonian fish species are endemic to the basin.[13] The remarkable species richness can in part be explained by the large differences between the various parts of the Amazon basin, resulting in many fish species that are endemic to small regions. For example, fauna in clearwater rivers differs from fauna in white and blackwater rivers, fauna in slow moving sections show distinct differences compared to that in rapids, fauna in small streams differ from that in major rivers, and fauna in shallow sections show distinct differences compared to that in deep parts.[14][15][16] By far the most diverse orders in the Amazon are Characiformes (43% of total fish species in the Amazon) and Siluriformes (39%), but other groups with many species include Cichlidae (6%) and Gymnotiformes (3%).[11]

In addition to major differences in behavior and ecology, Amazonian fish vary extensively in form and size. The largest, the arapaima and piraiba can reach 3 m (9.8 ft) or more in length and up to 200 kg (440 lb) in weight, making them some of the largest strict freshwater fish in the world.[17][18] The bull shark and common sawfish, which have been recorded far up the Amazon, may reach even greater sizes, but they are euryhaline and often seen in marine waters.[19][20] In contrast to the giants, there are Amazonian fish from several families that are less than 2 cm (0.8 in) long. The smallest are likely the Leptophilypnion sleeper gobies, which do not surpass 1 cm (0.4 in) and are among the smallest fish in the world.[21]

The Amazon supports very large fisheries, including well-known species of large catfish (such as Brachyplatystoma, which perform long breeding migrations up the Amazon), arapaima and tambaqui, and is also home to many species that are important in the aquarium trade, such as the oscar, discus, angelfish, Corydoras catfish and neon tetra.[11] Although the true danger they represent often is greatly exaggerated, the Amazon basin is home to several feared fish species such as piranhas (including the famous red-bellied), electric eel, river stingrays and candiru. Several cavefish species in the genus Phreatobius are found in the Amazon, as is the cave-dwelling Astroblepus pholeter in the far western part of the basin (Andean region).[22] The Tocantins basin, arguably not part of the Amazon basin, has several other cavefish species.[22] The deeper part of the major Amazonian rivers are always dark and a few species have adaptions similar to cavefish (reduced pigment and eyes). Among these are the knifefish Compsaraia and Orthosternarchus, some Cetopsis whale catfish (especially C. oliveirai), some Xyliphius and Micromyzon banjo catfish,[23] and the loricariid catfish Loricaria spinulifera, L. pumila, Peckoltia pankimpuju, Panaque bathyphilus and Panaqolus nix (these five also occur in "normal" forms of shallower waters).[24][25][26] The perhaps most unusual habitat used by Amazonian fish is land. The splash tetra is famous for laying its eggs on plants above water, keeping them moist by continuously splashing on them,[27] the South American lungfish can survive underground in a mucous cocoon during the dry season,[28] some small rivulid killifish can jump over land between water sources (sometimes moving relatively long distances, even uphill) and may deliberately jump onto land to escape aquatic predators,[29][30] and an undescribed species of worm-like Phreatobius catfish lives in waterlogged leaf litter near (not in) streams.[31][32]

Some of the major fish groups of the Amazon basin include:

- Order Gymnotiformes: Neotropical electric fishes

- Order Characiformes: characins, tetras and relatives

- Family Potamotrygonidae: river stingrays

- Family Arapaimidae: bonytongues

- Family Loricariidae: suckermouth catfishes

- Family Callichthyidae: armored catfishes

- Family Pimelodidae: pimelodid catfishes

- Family Trichomycteridae: pencil catfishes

- Family Auchenipteridae: driftwood catfishes

- Subfamily Cichlinae: pike cichlids, peacock cichlids and relatives

- Subfamily Geophaginae: Eartheaters and Neotropical dwarf cichlid

- Subfamily Poeciliinae: guppies and relatives

Insects

More than 90% of the animal species in the Amazon are insects,[33] of which about 40% are beetles (Coleoptera constituting almost 25% of all known types of animal life-forms.)[34][35][36]

Whereas all of Europe has some 321 butterfly species, the Manú National Park in Peru (4000 hectare-survey) has 2300 species, while Tambopata National Reserve (5500 hectare-survey) has at least 1231 species.

Climate and seasons

The Amazon River basin has a low-water season, and a wet season during which, the rivers flood the adjacent, low-lying forests. The climate of the basin is generally hot and humid. In some areas, however, the winter months (June–September) can bring cold snaps, fueled by Antarctic winds traveling along the adjacent mountain range. The average annual temperature is around 25-degree and 28 degree Celsius with no distinction between summer and winter seasons.

Human lifestyle

Amazonia is sparsely populated. There are scattered settlements inland, but most of the population lives in a few larger cities on the banks of the Amazon and other major rivers, such as in Iquitos - Loreto in Peru, Manaus-Amazonas State, and Belém, Pará. In many regions, the forest has been cleared for soya bean plantations and ranching (the most extensive non-forest use of the land); some of the inhabitants harvest wild rubber latex, and Brazilian nuts. This is a form of extractive farms, where the trees are not cut down. These are relatively sustainable operations in contrast to lumbering or agriculture dependent on clearing the rainforest. The people live in thatched houses shaped liked beehives. They also build apartment-like houses called "Maloca", with a steeply slanting roof.

Languages

The most widely spoken languages in the Amazon are Portuguese and Spanish. On the Brazilian side, Portuguese is spoken by at least 98% of the population, whilst in the Spanish-speaking countries, a large number of speakers of indigenous languages are present, though Spanish is predominant.

There are hundreds of native languages still spoken in the Amazon, most of which are spoken by only a handful of people, and thus are critically endangered.

Indigenous Peoples

For a list of the great number of indigenous peoples and cultures, still alive or already extinct, see Classification of indigenous peoples of the Americas and Indigenous peoples in Brazil.

The largest organization fighting for the indigenous peoples in this area is COICA. It is a supra organization encompassing all indigenous rights organizations working in the Amazon basin area, and covers the people living in several countries.

River commerce

The river is the principal path of transportation for people and produce in the regions, with transport ranging from balsa rafts and dugout canoes to hand built wooden river craft and modern steel hulled craft.

Agriculture

Seasonal floods excavate and redistribute nutrient-rich silt onto beaches and islands, enabling dry-season riverside agriculture of rice, beans, and corn on the river's shoreline without the addition of fertilizer, with additional slash and burn agriculture on higher floodplains. Fishing provides additional food year-round, and free-range chickens need little or no food beyond what they can forage locally. Charcoal made largely from forest and shoreline deadfall is produced for use in urban areas. Exploitation of bushmeat, particularly deer and turtles is common.

Extensive deforestation, particularly in Brazil, is leading to the extinction of known and unknown species, reducing biological diversity and adversely impacting soil, water, and air quality. A final part of the deforestation process is the large-scale production of charcoal for industrial processes such as steel manufacturing. Soils within the region are generally shallow and cannot be used for more than a few seasons without the addition of imported fertilizers and chemicals.

Global Ecological Role, Function for Climate Change

"The Amazon is a critical absorber of carbon of carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas produced by burning fossil fuels, like oil and coal. ... the Amazon's role is as a sink, draining heat-trapping carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Currently, the world is emitting around 40 billion tons of CO2 into the atmosphere every year. The Amazon absorbs 2 billion tons of CO2 per year (or 5% of annual emissions), making it a vital part of preventing climate change."[37]

"Amazon biodiversity also plays a critical role as part of global systems, influencing the global carbon cycle and thus climate change, as well as hemispheric hydrological systems, serving as an important anchor for South American climate and rainfall."[38]

See also

References

- Goulding, M., Barthem, R. B. and Duenas, R. (2003). The Smithsonian Atlas of the Amazon, Smithsonian Books ISBN 1-58834-135-6

- Roach, John (18 June 2007). "Amazon Longer Than Nile River, Scientists Say". National Geographic.

- Raymond E. Crist; Alarich R. Schultz; James J. Parsons (16 March 2018). "Amazon River". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- "Amazon river flowed into the Pacific millions of years ago". Mongabay. 24 October 2006. Archived from the original on 3 January 2013. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- Amazon, Plants. "Amazon plants and trees".

- "The Coolest Plants in the Amazon Rainforest". Rainforest Cruises.

- Butler, Rhett (31 July 2012). "Diversities of Image". Mongabay.com. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- Munn, C. A. 1994. Macaws: winged rainbows. National Geographic, 185, 118–140.

- Brightsmith D. J. (2004). "Effects of weather on parrot geophagy in Tambopata, Peru". Wilson Bulletin. 116 (2): 134–145. doi:10.1676/03-087b. S2CID 83509448.

- "Amazon Reptiles". Mongabay.com.

- Junk, W.J.; M.G.M. Soares; P.B. Bayley (2007), "Freshwater fishes of the Amazon River Basin: their biodiversity, fisheries, and habitats", Aquatic Ecosystem Health and Management, 10 (2): 153–173, doi:10.1080/14634980701351023, S2CID 83788515

- James S. Albert; Roberto E. Reis (2011). Historical Biogeography of Neotropical Freshwater Fishes. p. 308. ISBN 978-0-520-26868-5.

- Reis R.E.; Albert J.S.; Di Dario F.; Mincarone M.M.; Petry P.; Rocha L.A. (2016). "Fish biodiversity and conservation in South America". Journal of Fish Biology. 89 (1): 12–47. doi:10.1111/jfb.13016. PMID 27312713.

- Stewart D. J.; Ibarra M. (2002). "Comparison of Deep-River and Adjacent Sandy-Beach Fish Assemblages in the Napo River basin, Eastern Ecuador". Copeia. 2002 (2): 333–343. doi:10.1643/0045-8511(2002)002[0333:codraa]2.0.co;2.

- Mendonça, F. P., W. E. Magnusson, J. Zuanon and C. M. Taylor. (2005) Relationships between habitat characteristics and fish assemblages in small streams of Central Amazonia. Copeia 2005(4): 751–764

- Duncan, W.P.; and Fernandes, M.N. (2010). Physicochemical characterization of the white, black, and clearwater rivers of the Amazon Basin and its implications on the distribution of freshwater stingrays (Chondrichthyes, Potamotrygonidae). PanamJAS 5(3): 454–464.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2017). "Arapaima gigas" in FishBase. September 2017 version.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2017). "Brachyplatystoma filamentosum" in FishBase. September 2017 version.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2017). "Carcharhinus leucas" in FishBase. September 2017 version.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2017). "Pristis pristis" in FishBase. September 2017 version.

- Roberts, T.R. (2013). "Leptophilypnion, a new genus with two new species of tiny central Amazonian gobioid fishes (Teleostei, Eleotridae)". Aqua, International Journal of Ichthyology. 19 (2): 85–98.

- Romero, Aldemaro, ed. (2001). The Biology of Hypogean Fishes. Developments in environmental biology of fishes. 21. ISBN 978-1402000768.

- Fenolio, Danté (2016). Life in the Dark: Illuminating Biodiversity in the Shadowy Haunts of Planet Earth. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1421418636.

- Lujan, Nathan. K.; Chamon, Carine. C. (2008). "Two new species of Loricariidae (Teleostei: Silurifomes) from main channels of the upper and middle Amazon Basin, with discussion of deep water specialization in loricariids". Ichthyological Exploration of Freshwaters. 19: 271–282.

- Thomas, M.R.; L.H.R. Py-Daniel (2008). "Three new species of the armored catfish genus Loricaria (Siluriformes: Loricariidae) from river channels of the Amazon basin". Neotrop. Ichthyol. 6 (3): 379–394. doi:10.1590/S1679-62252008000300011.

- Cramer, C.A.; L.H.R. Py-Daniel (2015). "A new species of Panaqolus (Siluriformes: Loricariidae) from the rio Madeira basin with remarkable intraspecific color variation". Neotrop. Ichthyol. 13 (3): 461–470. doi:10.1590/1982-0224-20140099.

- Howard, B.C. (27 September 2013). Fish That Lay Eggs Out of the Water: Freshwater Species of the Week. National Geographic. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- SeriouslyFish. "Lepidosiren paradoxa". Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- Vermeulen, F. "The genus Rivulus". itrainsfishes.net. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- Turko, A.J.; P.A. Wright (2015). "Evolution, ecology and physiology of amphibious killifishes (Cyprinodontiformes)". Journal of Fish Biology. 87 (4): 815–835. doi:10.1111/jfb.12758. PMID 26299792.

- Planet Catfish. "Cat-eLog: Heptapteridae: Phreatobius: Phreatobius sp. (1)". Planet Catfish. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- Henderson, P.A.; I. Walker (1990). "Spatial organization and population density of the fish community of the litter banks within a central Amazonian blackwater stream". Journal of Fish Biology. 37 (3): 401–411. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.1990.tb05871.x.

- "Amazon Insects". Mongabay.com.

- Powell (2009)

- Rosenzweig, Michael L. (1995). Species Diversity in Space and Time. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-49952-1.

- Hunt, T.; Bergsten, J.; Levkanicova, Z.; Papadopoulou, A.; John, O. St.; Wild, R.; Hammond, P. M.; Ahrens, D.; Balke, M.; Caterino, M. S.; Gomez-Zurita, J.; Ribera, I.; Barraclough, T. G.; Bocakova, M.; Bocak, L.; Vogler, A. P.; et al. (2007). "A Comprehensive Phylogeny of Beetles Reveals the Evolutionary Origins of a Superradiation". Science. 318 (5858): 1913–1916. Bibcode:2007Sci...318.1913H. doi:10.1126/science.1146954. PMID 18096805. S2CID 19392955.

- https://phys.org/news/2019-08-role-amazon-global-climate.amp ; 2020 Jan. 12

- https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2019/05/22/why-the-amazons-biodiversity-is-critical-for-the-globe ; 2020 Jan. 12

Further reading

- Dematteis, Lou; Szymczak, Kayana (June 2008). Crude Reflections/Cruda Realidad: Oil, Ruin and Resistance in the Amazon Rainforest. City Lights Publishers. ISBN 978-0-87286-472-6.

- Acker, Antoine. "Amazon" (2015). University Bielefeld – Center for InterAmerican Studies.

External links

- Herndon and Gibbon Lieutenants United States Navy The First North American Explorers of the Amazon Valley, by Historian Normand E. Klare. Actual Reports from the explorers are compared with present Amazon basin conditions.

- Scientists find Evidence Discrediting Theory Amazon was Virtually Unlivable by The Washington Post

- "The Course of the River of the Amazons, Based on the Account of Christopher d’Acugna" from 1680