Languages of Brazil

Portuguese is the official and national language of Brazil[6] and is widely spoken by most of the population. The Portuguese dialects spoken in Brazil are collectively known as Brazilian Portuguese. The Brazilian Sign Language also has official status at the federal level.

| Languages of Brazil | |

|---|---|

| Official | Brazilian Portuguese |

| National | Portuguese - 98% |

| Significant | English - 7%, Spanish - 4%, Hunsrik - 1.5%[1] |

| Main | Portuguese[2][3][4] |

| Indigenous | Apalaí, Arára, Bororo, Canela, Carajá, Carib, Guarani, Kaingang, Nadëb, Nheengatu, Pirahã, Terena, Tucano, Tupiniquim, Ye'kuana |

| Regional | German, Italian, Japanese, Spanish (border areas), Polish, Ukrainian, Russian, English,[5] East Pomeranian, Chinese, Korean |

| Immigrant | German, Italian, Polish, Ukrainian, Russian, Japanese, Spanish, English, Chinese |

| Foreign | English, Spanish, German, Italian |

| Signed | Brazilian Sign Language Ka'apor Sign Language |

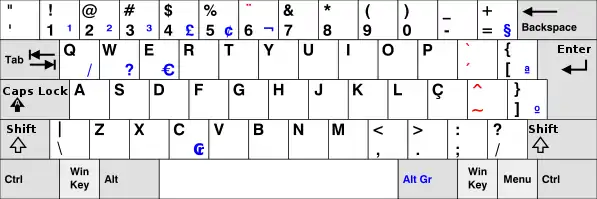

| Keyboard layout | |

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Brazil |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

| Cuisine |

| Religion |

| Art |

| Literature |

| Sport |

|

Aside from Portuguese, the country has also numerous minority languages, including indigenous languages, such as Nheengatu (a descendant of Tupi), and languages of more recent European and Asian immigrants, such as Italian, German and Japanese. In some municipalities, those minor languages have official status: Nheengatu, for example, is an official language in São Gabriel da Cachoeira, while a number of German dialects are official in nine southern municipalities. Hunsrik (also known as Riograndenser Hunsrückisch) is a germanic language[7] also spoken in Argentina, Paraguay and Venezuela,[8][9] which derived from the Hunsrückisch dialect. Hunsrik has official status in Antônio Carlos and Santa Maria do Herval, and is recognized by the state of Rio Grande do Sul as part of its historical and cultural heritage.[10] Polish and Ukrainian are largely spoken in the State of Paraná, immigrants originally from the former Austro-Hungarian Empire., the Galicia Province.

As of 2019, the population of Brazil speaks or signs approximately 228 languages, of which 217 are indigenous and 11 came with immigrants.[11] In 2005, fewer than 40,000 people (about 0.02% of the population at the time) spoke any of the indigenous languages.[12]

The Brazilian spelling of Portuguese is distinct from that of other Portuguese-speaking countries and is uniform across the country. With the implementation of the Orthographic Agreement of 1990, the orthographic norms of Brazil and Portugal have been largely unified, but still have some minor differences. Brazil enacted these changes in 2009 and Portugal enacted them in 2012.

In 2002, Brazilian Sign Language (Libras) was made the official language of the Brazilian deaf community.[13]

Overview

Before the first Portuguese explorers arrived in 1500, what is now Brazil was inhabited by several Amerindian peoples that spoke many different languages. According to Aryon Dall'Igna Rodrigues[14] there were six million Indians in Brazil speaking over 1,000 different languages. When the Portuguese settlers arrived, they encountered the Tupi people, who dominated most of the Brazilian coast and spoke a set of closely related languages. The Tupi called the non-Tupi peoples "Tapuias", a designation that the Portuguese adopted; however, there was little unity among the diverse Tapuia tribes other than their not being Tupi. In the first two centuries of colonization, a language based on Tupian languages known as Língua Geral ("General Language") was widely spoken in the colony, not only by the Amerindians, but also by the Portuguese settlers, the Africans and their descendants. This language was spoken in a vast area from São Paulo to Maranhão, as an informal language for domestic use, while Portuguese was the language used for public purposes. Língua Geral was spread by the Jesuit missionaries and Bandeirantes to other areas of Brazil where the Tupi language was not spoken. In 1775, Marquis of Pombal prohibited the use of Língua Geral or any other indigenous language in Brazil. However, as late as the 1940s, Língua Geral was widely spoken in some Northern Amazonian areas where the Tupi people were not present.

However, before that prohibition, the Portuguese language was dominant in Brazil. Most of the other Amerindian languages gradually disappeared as the populations that spoke them were integrated or decimated when the Portuguese-speaking population expanded to most of Brazil. The several African languages spoken in Brazil also disappeared. Since the 20th century there are no more records of speakers of African languages in the country. However, in some isolated communities settled by escaped slaves (Quilombo), the Portuguese language spoken by its inhabitants still preserves some lexicon of African origin, which is not understood by other Brazilians.[15] Due to the contact with several Amerindian and African languages, the Portuguese spoken in Brazil absorbed many influences from these languages, which led to a notable differentiation from the Portuguese spoken in Portugal.[16] Examples of widely used words of Tupi origin in Brazilian Portuguese include abacaxi ("pineapple"), pipoca ("popcorn"), catapora ("chickenpox"), and siri ("crab"). The names of thirteen of Brazil's twenty six states also have Amerindian origin.

Starting in the early 19th century, Brazil started to receive substantial immigration of non-Portuguese-speaking people from Europe and Asia. Most immigrants, particularly Italians[17] and Spaniards, adopted the Portuguese language after a few generations. Other immigrants, particularly Germans, Japanese, Arabs, Poles and Ukrainians,[17][18] preserved their languages for more generations. German-speaking[19] immigrants started arriving in 1824. They came not only from Germany, but also from other countries that had a substantial German-speaking population (Switzerland, Poland, Austria, Romania and Russia (Volga Germans). During over 100 years of continuous emigration, it is estimated that some 300,000 German-speaking immigrants settled in Brazil. Italian immigration started in 1875 and about 1.5 million Italians immigrated to Brazil until World War II. They spoke several dialects from Italy. Other sources of immigration to Brazil included Spaniards, Poles, Ukrainians, Japanese and Middle-easterns. With the notable exception of the Germans, who preserved their language for several generations, and in some degree the Japanese, Poles, Ukrainians, Arabs, Kurds and Italians, most of the immigrants in Brazil adopted Portuguese as their mother tongue after a few generations.[20][21]

Portuguese

Portuguese is the official language of Brazil and the primary language used in most schools and media. It is also used for all business and administrative purposes. Brazil is the only Portuguese-speaking nation in the Americas, giving it a national culture sharply distinct from its Spanish-speaking neighbours. Brazilian Portuguese has had its own development, influenced by the other European languages such as Italian and German in the South and Southeast, and several indigenous languages all across the country. For this reason, Brazilian Portuguese differs significantly from European Portuguese and other dialects of Portuguese-speaking countries, even though they are all mutually intelligible. Such differences occur in phonetics and lexicon and have been compared to the differences between British English and American English.

During the 18th century, other differences between the Brazilian and European Portuguese developed, mainly through the introduction of lexicon from African and Tupi languages, such as words related to fauna and flora. At that time Brazilian Portuguese failed to adopt linguistic changes taking place in Portugal produced by French influence. However, when John VI, the Portuguese king, and the royal entourage took refuge in Brazil in 1808 (when Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Portugal), he influenced the Portuguese spoken in the cities, making it more similar to the Portuguese of Portugal. After Brazilian independence in 1822, Brazilian Portuguese became influenced by Europeans who had migrated to the country. This is the reason that, in those areas (such as Rio de Janeiro and Recife), one finds variations in pronunciation (for instance, palatalization of post-vocalic /s/) and a few superficial lexical changes. These changes reflect the linguistics of the nationalities settling in each area. In the 20th century, the divide between the Portuguese and Brazilian variants of Portuguese widened as the result of new words for technological innovations. This happened because Portuguese lacked a uniform procedure for adopting such words. Certain words took different forms in different countries. For example: in Portugal one hears "comboio," and in Brazil one hears "trem", both meaning train. "Autocarro" in Portugal is the same thing as "ônibus" in Brazil, both meaning bus.[22]

Minority languages

Despite the fact that Portuguese is the official language of Brazil and the vast majority of Brazilians speak only Portuguese, there are several other languages spoken in the country. According to the president of IBGE (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics) there are an estimated 210 languages spoken in Brazil. Eighty are Amerindian languages, while the others are languages brought by immigrants. The 1950 Census was the last one to ask Brazilians which language they speak at home. Since then, the Census does not ask about language. However, the Census of 2010 asked respondents which languages they speak, allowing a better analysis of the languages spoken in Brazil.[23]

The first municipality to co-officialize other languages alongside Portuguese was São Gabriel da Cachoeira, in the state of Amazonas, with the languages Nheengatu, Tukano and Baniwa.[24][25] Since then, other Brazilian municipalities have co-officialized other languages.[26]

European immigrant languages

According to the 1940 Census, after Portuguese, German was the most widely spoken language in Brazil. Although the Italian immigration to Brazil was much more significant than the German one, the German language had many more speakers than the Italian one, according to the Census. The Census revealed that two-thirds of the children of German immigrants spoke German at home. In comparison, half of the children of Italians spoke Portuguese at home. The stronger preservation of the German language when compared to the Italian one has many factors: Italian is closer to Portuguese than German, leading to a faster assimilation of the Italian speakers. (One might compare this to the United States, where a huge wave of German immigrants almost completely switched to English and assimilated more thoroughly than the Italian-Americans.) Also, the German immigrants used to educate their children in German schools. The Italians, on the other hand, had less organized ethnic schools and the cultural formation was centered in church, not in schools. Most of the children of Italians went to public schools, where Portuguese was spoken.[27] Until World War II, some 1.5 million Italians had immigrated to Brazil, compared to only 250,000 Germans. However, the 1940 Census revealed that German was spoken as a home language by 644,458 people, compared to only 458,054 speakers of Italian.[28]

Spaniards, who formed the third largest immigrant group in Brazil (after the Portuguese and Italians) were also quickly assimilated into the Portuguese-speaking majority. Spanish is similar to Portuguese, which led to a fast assimilation. Moreover, many of the Spanish immigrants were from Galicia, where they also speaks Galician, which is closer to Portuguese, sometimes even being considered two dialects of the same language.[29][30] Despite the large influx of Spanish immigrants to Brazil from 1880 to 1930 (over 700,000 people) the Census of 1940 revealed that only 74,000 people spoke Spanish in Brazil.

Other languages such as Polish and Ukrainian, along with German and Italian, are spoken in rural areas of Southern Brazil, by small communities of descendants of immigrants, who are for the most part bilingual. There are whole regions in southern Brazil where people speak both Portuguese and one or more of these languages. For example, it is reported that more than 90% of the residents of the small city of Presidente Lucena, located in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, speak Hunsrik, a language[7] derived from the Hunsrückisch dialect of German.[31] Hunsrik, or Riograndenser Hunsrückisch, has around 3,000,000[32] native speakers in Brazil, while also having some speakers in Argentina, Paraguay and Venezuela. The language is most used in the countryside of the South Region states of Brazil, with a considerable amount of native speakers using it as their main or even only language.[7]

Some immigrant communities in southern Brazil, chiefly the German and the Italian ones, have lasted long enough to develop distinctive dialects from their original European sources. For example, Brazilian German, a broad category which includes the Hunsrik language, but also East Pomerian and Plautdietsch dialects. In the Serra Gaúcha region, we can find Italian dialects such as Talian or italiano riograndense, based on the Venetian language.

Other German dialects were transplanted to this part of Brazil. For example, the Austrian dialect spoken in Dreizehnlinden or Treze Tílias in the state of Santa Catarina; or the dialect Schwowisch (Standard German: "Schwäbisch"), from Donauschwaben immigrants, is spoken in Entre Rios, Guarapuava, in the state of Paraná; or the East Pomeranian dialect spoken in many different parts of southern Brazil (in the states of Rio Grande do Sul, Santa Catarina, Paraná, Espírito Santo, São Paulo, etc.). Plautdietsch is spoken by the descendants of Russian Mennonites. However, these languages have been rapidly replaced by Portuguese in the last few decades, partly due to a government decision to integrate immigrant populations. Today, states like Rio Grande do Sul are trying to reverse that trend and immigrant languages such as German and Italian are being reintroduced into the curriculum again, in communities where they originally thrived. Meanwhile, on the Argentinian and Uruguayan border regions, Brazilian students are being introduced to the Spanish language.

Asian languages

In the city of São Paulo, Korean, Chinese and Japanese can be heard in the immigrants districts, like Liberdade. A Japanese-language newspaper, the São Paulo Shinbun, had been published in the city of São Paulo since 1946, still printing paper editions until January 2019.[33] There is a significant community of Japanese speakers in São Paulo, Paraná, Mato Grosso do Sul, Pará and Amazonas. Much smaller groups exist in Santa Catarina, Rio Grande do Sul and other parts of Brazil. Some Chinese, especially from Macau, speak a Portuguese-based creole language called Macanese (patuá or macaísta), aside from Hakka, Mandarin and Cantonese. Brazil has the largest Japanese population outside of Japan.

Indigenous languages

Many Amerindian minority languages are spoken throughout Brazil, mostly in Northern Brazil. Indigenous languages with about 10,000 speakers or more are Ticuna (language isolate), Kaingang (Gean family), Kaiwá Guarani, Nheengatu (Tupian), Guajajára (Tupian), Macushi (Cariban), Terena (Arawakan), Xavante (Gean) and Mawé (Tupian). Tucano (Tucanoan) has half that number, but is widely used as a second language in the Amazon.

One of the two Brazilian línguas gerais (general languages), Nheengatu, was until the late 19th century the common language used by a large number of indigenous, European, African, and African-descendant peoples throughout the coast of Brazil—it was spoken by the majority of the population in the land. It was proscribed by the Marquis of Pombal for its association with the Jesuit missions. A recent resurgence in popularity of this language occurred, and it is now an official language in the city of São Gabriel da Cachoeira. Today, in the Amazon Basin, political campaigning is still printed in this Tupian language.

There is also an indigenous sign language, the Ka'apor Sign Language.[34][35][36]

Below is a full list of indigenous language families and isolates of Brazil based on Campbell (2012).[37] The Macro-Jê classification follows that of Nikulin (2020).[38] Additional extinct languages of Northeast Brazil have also been included from Meader (1978) and other sources.[39]

- Tupían

- Arawakan

- Cariban

- Macro-Jê

- Boróro

- Purí

- Guató

- Karirí

- Otí

- Chapacuran

- Pano–Takanan

- Nadahup (Makuan)

- Tucanoan

- Arawan

- Guaicuruan

- Katukinan

- Muran

- Nambikwaran

- Tikuna–Yuri

- Yanomaman

- Aikanã

- Awaké

- Irantxe

- Kanoê

- Kwaza

- Jukude (Maku)

- Matanawí

- Taruma

- Trumai

- Boran

- Xukuruan

- Natú

- Pankararú

- Tuxá

- Wamoé (Atikum)

- Kambiwá

- Xocó

- Yaté (Fulniô)

- Baenan

- Kaimbé

- Katembri

- Tarairiú

- Gamela

Bilingualism

Spanish is understood to various degrees by many but not all Brazilians, due to the similarities of the languages. However, it is hardly spoken well by individuals who have not taken specific education in the language, due to the substantial differences in phonology between the two languages. In some parts of Brazil, close to the border of Brazil with Spanish-speaking countries, Brazilians will use a rough mixture of Spanish and Portuguese that is sometimes known as Portuñol to communicate with their neighbors on the other side of the border; however, these Brazilians continue to speak Portuguese at home. In recent years, Spanish has become more popular as a second or third language in Brazil due in large part to the economic advantages that Spanish fluency brings in doing business with other countries in the region, since seven of the 11 countries that border Brazil use Spanish as an official language. However, it falls behind English due to lack of interest by Brazilians in learning Spanish.

In São Paulo, the German-Brazilian newspaper Brasil-Post has been published for over fifty years. There are many other media organizations throughout the land specializing either in church issues, music, language etc.

The online newspaper La Rena is in Talian dialect and it offers Talian lessons. There are many other non-Portuguese publications, bilingual web sites, radio and television programs throughout the country.

On the Paraná state, there are several communities of Poles, Ukrainians and other Slavics that live in rural areas and in some municipalities such as Curitiba, Irati, Guarapuava, Ponta Grossa and Prudentópolis. Polish and Ukrainian are still spoken, mainly by oldest people. In the City of Foz do Iguaçu (on the border with Paraguay and Argentina), there are many Arabic speakers, these people are mainly immigrants from Palestine, Lebanon and Syria.

On the Rio Grande do Sul state, there are several German and Italian colonized cities, communities and groups. Most small cities have German or Italian as their second language. In the capital Porto Alegre, it is easy to find people who speak one of those or both.

There are also at least two ethnic neighborhoods in the country: Liberdade, bastion of Japanese immigrants,[40][41] and Bixiga, stronghold of Italian immigrants,[42][43] both in São Paulo; however, these neighborhoods do not count yet with specific legislation for the protection of Japanese and Italian languages in these sites.[44][45]

Co-official languages in Brazil

The 21st century has seen the growth of a trend of co-official languages in cities populated by immigrants (such as Italian and German) or indigenous in the north, both with support from the Ministry of Tourism, as was recently established in Santa Maria de Jetibá, Pomerode and Vila Pavão,[46] where German also has co-official status.[47]

The first municipality to adopt a co-official language in Brazil was São Gabriel da Cachoeira, in 2002.[48][49] Since then, other municipalities have attempted to adopt their own co-official languages.

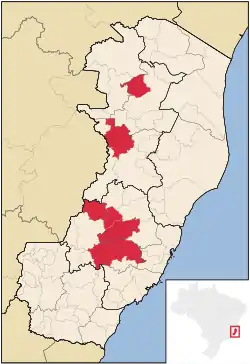

The states of Santa Catarina[50][51][52] and Rio Grande do Sul have Talian officially approved as a heritage language in these states,[53] and Espírito Santo has the East Pomeranian dialect, along with the German language as cultural heritage.[54][55][56][57] [58] [59]

Also in production is the documentary video Brasil Talian,[60] with directed and written by André Costantin and executive producer of the historian Fernando Roveda.[61] The pre-launch occurred on 18 November 2011, the date that marked the start of production of the documentary.[62]

Officialization of languages as a linguistic or cultural heritage

Brazilian states with linguistic heritages officially approved statewide

- Espírito Santo (East Pomeranian and German)[63][64][65][66][58][59]

- Rio Grande do Sul (Talian[67] and Hunsrik[68][69])

- Rio de Janeiro (Yoruba)[70][71][72][73]

- Santa Catarina (Talian)[74][75][76]

Brazilian municipalities that have some language as intangible cultural heritage

Municipalities that have co-official indigenous languages

Municipalities that have co-official allochthonous languages

Municipalities that have co-official Talian language (or Venetian dialect)

- Antônio Prado, Rio Grande do Sul[103]

- Bento Gonçalves, Rio Grande do Sul[104][105][106]

- Camargo, Rio Grande do Sul[100]

- Caxias do Sul, Rio Grande do Sul[107]

- Fagundes Varela, Rio Grande do Sul[108]

- Flores da Cunha, Rio Grande do Sul[109][110][111]

- Guabiju, Rio Grande do Sul[100]

- Ivorá, Rio Grande do Sul[100]

- Nova Pádua, Rio Grande do Sul[100]

- Nova Roma do Sul, Rio Grande do Sul[112][113]

- Paraí, Rio Grande do Sul[114]

- Serafina Corrêa, Rio Grande do Sul[115][116]

- Nova Erechim, Santa Catarina[117][118]

Municipalities that have co-official East Pomeranian language

- Domingos Martins, Espírito Santo[54][119][120]

- Itarana, Espírito Santo[121][122]

- Laranja da Terra, Espírito Santo[54][120]

- Pancas, Espírito Santo[54][123][124]

- Santa Maria de Jetibá, Espírito Santo[54][125]

- Vila Pavão, Espírito Santo[54][126]

- Itueta, Minas Gerais (only in the district of Vila Nietzel)[127][128][129]

- Pomerode, Santa Catarina[130]

- Canguçu, Rio Grande do Sul[131]

- Espigão d'Oeste, Rondônia (under approval)[132][133][134][135]

Municipalities that have co-official Plattdüütsch (Low German) language

Municipalities that have co-official language Hunsrik

- Antônio Carlos, Santa Catarina[137]

- Treze Tílias, Santa Catarina (language teaching is compulsory in schools, standing on stage in public official of the municipality)[138][139][140]

- Santa Maria do Herval, Rio Grande do Sul[141][142][143][144]

Municipalities that have the Trentino dialect as their co-official language

Officialization in teaching

Municipalities in which the teaching of the German language is mandatory

- Nova Petrópolis, Rio Grande do Sul[148][149][150][151]

Municipalities in which the teaching of the Italian language is mandatory

- Santa Teresa, Espírito Santo,[152] known as the state capital of Italian immigration[153]

- Venda Nova do Imigrante, Espírito Santo[154][155]

- Vila Velha, Espírito Santo[152]

- Francisco Beltrão, Paraná[156][157]

- Antônio Prado, Rio Grande do Sul[158][159]

- Brusque, Santa Catarina[160][161][162][163]

- Criciúma, Santa Catarina[164][165]

- Bragança Paulista, São Paulo[166]

See also

- Indigenous languages of South America

- List of Brazil state name etymologies

- Reintegracionism (About Portuguese and Galician)

References

- Hunsrik, Ethnologue (2016).

- "Hunsrückish". Ethnologue. Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- "DW". DW. Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- "Standard German". Ethnologue. Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- "Geography of Brazil". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 2016. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- According to the Brazilian Constitution, article 13: A língua portuguesa é o idioma oficial da República Federativa do Brasil. "The Portuguese language is the official language of the Federative Republic of Brazil".

- Altenhofen, Cleo Vilson; Morello, Rosângela (2018). Hunsrückisch : inventário de uma língua do Brasil. Garapuvu. ISBN 978-85-907418-7-9.

- https://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:mctF74TY7voJ:https://odiario.net/projeto-hunsrik-completa-15-anos-no-mes-de-fevereiro/+&cd=6&hl=es-419&ct=clnk&gl=ve

- https://odiario.net/editorias/geral/projeto-hunsrik-completa-15-anos-no-mes-de-fevereiro/

- "Lei N.º 14.061, de 23 de julho de 2012". web.archive.org. 30 March 2019. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- Ethnologue

- Aryon Dall'Igna Rodrigues (April 2005). "Sobre as línguas indígenas e sua pesquisa no Brasil" (in Portuguese). Sociedade Brasileira para o Progresso da Ciência. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- Piconi, Larissa Bassi (2014). "Teaching languages to deaf students in Brazil at the intersection of discourses". Revista Brasileira de Linguística Aplicada. 14 (4): 881–904. doi:10.1590/S1984-63982014005000022. ISSN 1984-6398.

- "A última falante viva de xipaia". Revista Época. Editora Globo. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- Línguas Africanas

- Línguas indígenas

- "Brazil". Ethnologue.

- "Hunsrik". Ethnologue.

- "German" here meaning varied Germanic dialects spoken in Germany and other countries, not standard German.

- Línguas europeias

- Políticas lingüísticas e a conservação da língua alemã no Brasil

- "History – Brazilian Portuguese". Archived from the original on 9 March 2013. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- Censo 2010 fará a soma de casais homossexuais

- Language Born of Colonialism Thrives Again in Amazon New York Times. Retrieved 22 September 2008

- "Línguas indígenas ganham reconhecimento oficial de municípios". Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- Cooficialização de línguas no Brasil: características, desdobramentos e desafios, third page.

- The Italian Immigration and Education

- Census of 1940

- Spanish people in Brazil

- "O Brasil como país de destino para imigrantes". Archived from the original on 25 April 2009. Retrieved 29 September 2009.

- Rota Romântica Archived 6 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- Hunsrik, Ethnologue (2016).

- São Paulo Shimbun – Brazilian Newspaper in Japanese Archived 14 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- Língua de Sinais Ka'apor Brasileira

- O fim do isolamento dos índios surdos

- Línguas de sinais de comunidades isoladas encontradas no Brasil

- Campbell, Lyle (2012). "Classification of the indigenous languages of South America". In Grondona, Verónica; Campbell, Lyle (eds.). The Indigenous Languages of South America. The World of Linguistics. 2. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 59–166. ISBN 978-3-11-025513-3.

- Nikulin, Andrey. 2020. Proto-Macro-Jê: um estudo reconstrutivo. Doctoral dissertation, University of Brasília.

- Meader, Robert E. (1978). Indios do Nordeste: Levantamento sobre os remanescentes tribais do nordeste brasileiro (in Portuguese). Brasilia: SIL International.

- Portal do Bairro Liberdade

- História da Imigração Japonesa

- Bairro do Bixiga

- Bairro do Bixiga, reduto italiano em São Paulo

- "Bexiga e Liberdade". Archived from the original on 20 November 2012. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- Os italianos de Bixiga, São Paulo

- "Vila Pavão, Uma Pomerânia no norte do Espírito Santo" (in Portuguese). Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- "Pomerode institui língua alemã como co-oficial no Município" (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 30 May 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- "Lei municipal oficializa línguas indígenas em São Gabriel da Cachoeira" (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 18 September 2011. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- "Na Babel brasileira, português é 2ª língua - Flávia Martin e Vitor Moreno, enviados especiais a Sâo Gabriel da Cachoeira (AM)]" (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 4 June 2012. Retrieved 16 December 2012.

- "LEI Nº 14.951" (in Portuguese). Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- "Rotary apresenta ações na Câmara. FEIBEMO divulga cultura italiana" (in Portuguese). Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- "Fóruns sobre o Talian - Eventos comemoram os 134 anos da imigração italiana" (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 30 July 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- "Aprovado projeto que declara o Talian como patrimônio do RS]" (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 27 January 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- "O povo pomerano no ES" (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 21 December 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- "Plenário aprova em segundo turno a PEC do patrimônio" (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 27 January 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- "Emenda Constitucional na Íntegra" (PDF) (in Portuguese). Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- "ALEES - PEC que trata do patrimônio cultural retorna ao Plenário" (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 14 December 2013. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- http://titus.uni-frankfurt.de/didact/karten/germ/deutdin.htm

- http://www.lerncafe.de/aus-der-welt-1142/articles/pommern-in-brasilien.html

- "Filme Brasil Talian é pré-lançado" (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- "Brasil Talian documentado em filme" (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- "Marisa busca apoio para documentário sobre cultura italiana produzido em Antonio Prado" (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- O povo pomerano no ES Archived 21 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Plenário aprova em segundo turno a PEC do patrimônio Archived 27 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Emenda Constitucional na Íntegra

- "ALEES - PEC que trata do patrimônio cultural retorna ao Plenário". Archived from the original on 14 December 2013. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- Aprovado projeto que declara o Talian como patrimônio do RS Archived 27 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine, accessed on 21 August 2011

- LEI 14.061 - DECLARA INTEGRANTE DO PATRIMÔNIO HISTÓRICO E CULTURAL DO ESTADO DO RIO GRANDE DO SUL A "LÍNGUA HUNSRIK", DE ORIGEM GERMÂNICA

- LEI Nº 14.061, 23 July 2012 - Declara integrante do patrimônio histórico e cultural do estado do Rio Grande do Sul a língua hunsrik, de origem germânica

- Lei nº 8085 de 28 de agosto de 2018 do Rio de janeiro

- A partir de agora o idioma Iorubá é patrimônio imaterial do Rio

- Idioma iorubá é declarado patrimônio imaterial do Rio de Janeiro

- Idioma Iorubá é oficialmente patrimônio imaterial do Rio

- LEI Nº 14.951, 11 November 2009

- Rotary apresenta ações na Câmara. FEIBEMO divulga cultura italiana

- Fóruns sobre o Talian - Eventos comemoram os 134 anos da imigração italiana

- Língua Alemã agora é patrimônio cultural imaterial de Blumenau, NSC Total

- Língua alemã agora é patrimônio cultural da cidade, Blumenau

- Língua Alemã é patrimônio cultural de Blumenau, Informe Blumenau

- Lei confirma o Talian como segunda língua oficial de Caxias do Sul

- Lei Nº 8208, de 09 de outubro de 2017 - Institui o Talian como a segunda língua oficial do Município de Caxias do Sul.

- Aprovado projeto que reconhece o Talian como patrimônio imaterial de Caxias, LEOUVE

- Projeto que torna o Talian patrimônio imaterial de Caxias segue para avaliação de Guerra, Pioneiro

- Projeto que torna iorubá patrimônio de Salvador é aprovado na Câmara, Correio

- Depois do Rio, iorubá vira patrimônio imaterial de Salvador, Hypeness

- Idioma Iorubá se torna patrimônio imaterial de Salvador, Alô Alô Bahia

- Neto sanciona lei que torna Iorubá patrimônio imaterial de Salvador, Bahia Notícias

- Aprovada a lei que oficializa a língua alemã como patrimônio cultural do município de Santa Cruz, Portal Arauto

- Santa Cruz terá placas em alemão para identificar localidades, Gaz

- "Lei municipal oficializa línguas indígenas em São Gabriel da Cachoeira]" (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 18 September 2011. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- "Na Babel brasileira, português é 2ª língua - Flávia Martin e Vitor Moreno, enviados especiais a Sâo Gabriel da Cachoeira (AM)]" (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 4 June 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- "Município do MS adota o guarani como língua oficial]" (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- "Paranhos poderá ter a co-oficialização de uma língua Indígena]" (in Portuguese). Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- Co-officialization of the Mebengokre (Kayapo) language in the municipality of São Félix do Xingu: Part One, Part Two, Part Three, Part Four

- Município de Roraima co-oficializa línguas indígenas Macuxi e Wapixana

- Wapichana e Macuxi viram línguas oficiais em município de Roraima

- Línguas indígenas Macuxi e Wapixana se tornam co-oficiais em município de Roraima

- Idiomas indígenas Macuxi e Wapixana são oficializados em município de Roraima

- A Cooficialização de línguas no Brasil: Competência legislativa e empoderamento de línguas minoritárias, table 1, page 13

- Línguas cooficializadas nos municípios brasileiros, Instituto de Investigação e Desenvolvimento em Política Linguística (IPOL)

- Quadro – Línguas cooficializadas no Brasil, municípios e respectivas leis

- "Tocantínia passa a ter Akwê Xerente como língua co-oficial e recebe Centro de Educação Indígena" (in Portuguese). Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- Lei municipal Nº 3017, de 28 de setembro de 2016

- Aprovada em primeira votação projeto que torna o Talian segunda língua oficial de Bento Gonçalves

- Co-oficialização do Talian é oficializada pela câmara de Bento Golçalves

- "Câmara Bento – Projeto do Executivo é aprovado e Talian se torna a língua co-oficial". Archived from the original on 9 June 2016. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- "Lei confirma o Talian como segunda língua oficial de Caxias do Sul". Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- Lei de Instituição do Talian - Lei Nº 1.922 de 10 de junho de 2016

- "Talian pode ser língua cooficial de Flores da Cunha". Archived from the original on 15 June 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- "Talian é língua cooficial de Flores da Cunha". Archived from the original on 15 June 2016. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- "Flores da Cunha (RS) - Projeto pretende instituir o "Talian" como língua co oficial no Município". Archived from the original on 8 August 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- Lei Nº 1310 de 16 de outubro de 2015 - Dispõe sobre a cooficialização da língua do "talian", à língua portuguesa, no município de Nova Roma do Sul"

- O Talian agora é a língua co-oficial de Nova Roma do Sul, município de Nova Roma do Sul

- Talian: protagonismo na luta pelo reconhecimento cultural e fortalecimento pela lei de cooficialização

- "Vereadores aprovam o talian como língua co-oficial do município" (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- "Talian em busca de mais reconhecimento" (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 1 August 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- Cooficialização do Talian - Nova Erechim, SC

- Cultura - Talian - A língua co-oficial de Nova Erechim

- "A escolarização entre descendentes pomeranos em Domingos Martins" (PDF) (in Portuguese). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 December 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- "A co-oficialização da língua pomerana" (PDF) (in Portuguese). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 December 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- Município de Itarana participa de ações do Inventário da Língua Pomerana, Prefeitura Municipal de Itarana

- «Lei Municipal nº 1.195/2016 de Itarana/ES». itarana.es.gov.br

- "Pomerano!?" (in Portuguese). Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- "No Brasil, pomeranos buscam uma cultura que se perde" (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 28 March 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- "Lei dispõe sobre a cooficialização da língua pomerana no município de Santa maria de Jetibá, Estado do Espírito Santo" (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- "Vila Pavão, Uma Pomerânia no norte do Espirito Santo" (in Portuguese). Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- "Descendentes de etnia germânica vivem isolados em área rural de Minas" (in Portuguese). Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- "Pomeranos em busca de recursos federais" (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- "Resistência cultural - Imigrantes que buscaram no Brasil melhores condições de vida, ficaram isolados e sem apoio do poder público" (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 20 November 2015. Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- "Pomerode institui língua alemã como co-oficial no Município" (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 30 May 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- "Bancada PP comenta cooficialização pomerana em Canguçu". Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- "Ontem e hoje : percurso linguistico dos pomeranos de Espigão D'Oeste-RO" (in Portuguese). Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- "Sessão Solene em homenagem a Comunidade Pomerana" (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 21 December 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- "Percurso linguistico dos pomeranos de Espigão D Oeste-RO]" (in Portuguese). Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- "Comunidade Pomerana realiza sua tradicional festa folclórica" (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 6 February 2015. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- Lei nº 1302, de 16 de março de 2016

- Cooficialização da língua alemã em Antônio Carlos Archived 2 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- "Vereadores de Treze Tílias se reuniram ontem" (in Portuguese). Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- TREZE TÍLIAS

- "Um pedaço da Aústria no Brasil" (in Portuguese). Treze Tílias. Archived from the original on 13 May 2008. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- A sala de aula de alemão para falantes de dialeto: realidades e mitos

- Brasil: dialeto do baixo-alemão torna-se segunda língua oficial de cidade gaúcha

- Apresentando... Santa Maria do Herval

- "Dialetos Hunsrik e Talian na ofensiva no Sul] - Em Santa Maria do Herval, regiăo de Novo Hamburgo, RS, surge forte a mobilizaçăo em favor do Hunsrik - a faceta brasileira/latino-americana do Hunsrückisch. Em Serafina Correa, RS, floresce o talian" (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- Sancionada Lei que torna Dialeto Trentino Língua Cooficial de Rodeio, Vale do Itajaí Notícias

- Dialeto Trentino é Língua Cooficial de Rodeio, Vale do Itajaí Notícias

- Dialeto Trentino se torna a segunda língua oficial de cidade no Vale do Itajaí, NSC Total

- Câmara Municipal de Vereadores de Nova Petrópolis

- "Ata 047/2010" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- Art. 153 § 3º da Lei Orgânica Archived 19 February 2013 at Archive.today

- Em Nova Petrópolis 100% da população é alfabetizada Archived 22 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine, quinto parágrafo

- La rivincita dell’italiano

- Lei Nº 10.378, Espírito Santo

- Língua italiana na rede municipal de ensino Archived 22 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- "Aprovado em primeira votação, projeto emendado propõe um ano de caráter experimental em Venda Nova". Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- LEI Nº 3018/2003 - 02.10.03 - Dispõe sobre a oficialização de aulas de língua italiana nas escolas da Rede Municipal de Ensino

- Lei Ordinária nº 3018/2003 de Francisco Beltrão, dispõe sobre a oficialização de aulas de língua italiana nas escolas

- "Elaboração de Projeto de Lei para o ensino obrigatório da língua italiana nas escolas municipais" (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 24 July 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- "Língua italiana em Antônio Prado, Italiano integra currículo escolar" (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 15 April 2015. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- Lei 3113/08, Brusque - Institui o ensino da língua italiana no currículo da rede municipal de ensino e dá outras provicências

- Lei 3113/08 | Lei nº 3113 de 14 de agosto de 2008 de Brusque

- Art. 1 da Lei 3113/08, Brusque

- "Secretaria de Educação esclarece a situação sobre o Ensino da Língua Italiana". Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- Lei 4159/01 | Lei nº 4159 de 29 de maio de 2001 de Criciuma

- Lei nº 4.159 de 29 de Maio de 2001 - Institui a disciplina de língua italiana

- "Lei 2953/96 | Lei nº 2953 de 30 de setembro de 1996". Archived from the original on 10 January 2020. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

External links

- Co-officialized languages in Brazilian municipalities, Instituto de Investigação e Desenvolvimento em Política Linguística (IPOL)

- Swadesh Listas of Brazilian Native Languages