Epidemiology of depression

The epidemiology of depression has been studied across the world. Depression is a major cause of morbidity worldwide, as the epidemiology has shown.[2] Lifetime prevalence estimates vary widely, from 3% in Japan to 17% in the United States. Epidemiological data shows higher rates of depression in the Middle East, North Africa, South Asia and America than in other countries.[3] Among the 10 countries studied, the number of people who would suffer from depression during their lives falls within an 8–12% range in most of them.[4][5]

In North America, the probability of having a major depressive episode within any year-long period is 3–5% for males and 8–10% for females.[6][7]

Demographic dynamics

Population studies have consistently shown major depression to be about twice as common in women as in men, although it is as of yet unclear why this is so.[8] The relative increase in occurrence is related to pubertal development rather than chronological age, reaches adult ratios between the ages of 15 and 18, and appears associated with psychosocial more than hormonal factors.[8]

People are most likely to suffer their first depressive episode between the ages of 30 and 40, and there is a second, smaller peak of incidence between ages 50 and 60.[9] The risk of major depression is increased with neurological conditions such as stroke, Parkinson's disease, or multiple sclerosis and during the first year after childbirth.[10] The risk of major depression has also been related to environmental stressors faced by population groups such as war combatants or physicians in training.[11][12]

It is also more common after cardiovascular illnesses, and is related more to a poor outcome than to a better one[13][14] Studies conflict on the prevalence of depression in the elderly, but most data suggest there is a reduction in this age group.[15] Depressive disorders are most common in urban than in rural population and, in general, the prevalence is higher in groups with adverse socio-economic factors (for example in homeless people)[16]

Data on the relative prevalence of major depression among different ethnic groups have reached no clear consensus. However, the only known study to have covered dysthymia specifically found it to be more common in African and Mexican Americans than in European Americans.[17]

Projections indicate that depression may be the second leading cause of life lost after heart disease by 2020.[18]

In 2016, a study found an association between hormonal contraception and depression.[19]

By country

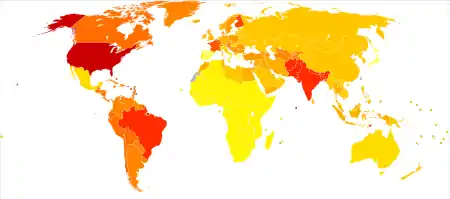

Age-standardised disability-adjusted life year (DALY) rates per 10,000 inhabitants in 2004.[20]

| Rank | Country | DALY rate |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1,454.74 | |

| 2 | 1,424.48 | |

| 3 | 1,404.10 | |

| 4 | 1,401.53 | |

| 5 | 1,400.84 | |

| 6 | 1,400.42 | |

| 7 | 1,396.10 | |

| 8 | 1,391.61 | |

| 9 | 1,385.53 | |

| 10 | 1,385.14 | |

| 11 | 1,344.13 | |

| 12 | 1,273.92 | |

| 13 | 1,248.47 | |

| 14 | 1,244.46 | |

| 15 | 1,234.32 | |

| 16 | 1,221.23 | |

| 17 | 1,177.03 | |

| 18 | 1,170.73 | |

| 19 | 1,161.56 | |

| 20 | 1,161.25 | |

| 21 | 1,157.07 | |

| 22 | 1,156.30 | |

| 23 | 1,156.07 | |

| 24 | 1,141.79 | |

| 25 | 1,133.20 | |

| 26 | 1,120.05 | |

| 27 | 1,114.11 | |

| 28 | 1,112.94 | |

| 29 | 1,112.45 | |

| 30 | 1,112.10 | |

| 31 | 1,110.76 | |

| 32 | 1,110.18 | |

| 33 | 1,110.00 | |

| 34 | 1,108.30 | |

| 35 | 1,103.93 | |

| 36 | 1,100.10 | |

| 37 | 1,099.51 | |

| 38 | 1,099.29 | |

| 39 | 1,098.66 | |

| 40 | 1,098.21 | |

| 41 | 1,098.14 | |

| 42 | 1,097.85 | |

| 43 | 1,095.86 | |

| 44 | 1,095.76 | |

| 45 | 1,094.66 | |

| 46 | 1,094.65 | |

| 47 | 1,094.64 | |

| 48 | 1,094.20 | |

| 49 | 1,093.04 | |

| 50 | 1,091.56 | |

| 51 | 1,088.72 | |

| 52 | 1,087.50 | |

| 53 | 1,087.25 | |

| 54 | 1,086.82 | |

| 55 | 1,086.71 | |

| 56 | 1,085.63 | |

| 57 | 1,085.28 | |

| 58 | 1,083.23 | |

| 59 | 1,060.42 | |

| 60 | 1,056.60 | |

| 61 | 1,047.94 | |

| 62 | 1,044.53 | |

| 63 | 1,043.18 | |

| 64 | 1,042.62 | |

| 65 | 1,041.97 | |

| 66 | 1,040.66 | |

| 67 | 1,039.45 | |

| 68 | 1,037.76 | |

| 69 | 1,037.51 | |

| 70 | 996.780 | |

| 71 | 960.624 | |

| 72 | 959.325 | |

| 73 | 959.222 | |

| 74 | 956.319 | |

| 75 | 955.986 | |

| 76 | 955.011 | |

| 77 | 939.728 | |

| 78 | 936.667 | |

| 79 | 936.319 | |

| 80 | 934.095 | |

| 81 | 931.894 | |

| 82 | 931.842 | |

| 83 | 931.675 | |

| 84 | 931.414 | |

| 85 | 930.510 | |

| 86 | 929.554 | |

| 87 | 927.707 | |

| 88 | 925.765 | |

| 89 | 923.746 | |

| 90 | 923.086 | |

| 91 | 923.076 | |

| 92 | 922.893 | |

| 93 | 921.373 | |

| 94 | 919.740 | |

| 95 | 919.158 | |

| 96 | 918.331 | |

| 97 | 917.689 | |

| 98 | 912.718 | |

| 99 | 911.415 | |

| 100 | 909.399 | |

| 101 | 909.227 | |

| 102 | 904.903 | |

| 103 | 903.122 | |

| 104 | 900.547 | |

| 105 | 900.546 | |

| 106 | 900.533 | |

| 107 | 900.401 | |

| 108 | 900.169 | |

| 109 | 899.281 | |

| 110 | 899.004 | |

| 111 | 898.923 | |

| 112 | 898.831 | |

| 113 | 896.317 | |

| 114 | 895.616 | |

| 115 | 892.281 | |

| 116 | 888.392 | |

| 117 | 877.069 | |

| 118 | 868.902 | |

| 119 | 866.490 | |

| 120 | 863.421 | |

| 121 | 862.099 | |

| 122 | 861.586 | |

| 123 | 860.070 | |

| 124 | 858.312 | |

| 125 | 857.445 | |

| 126 | 857.314 | |

| 127 | 856.718 | |

| 128 | 855.825 | |

| 129 | 855.363 | |

| 130 | 855.207 | |

| 131 | 855.040 | |

| 132 | 851.065 | |

| 133 | 847.175 | |

| 134 | 847.062 | |

| 135 | 846.943 | |

| 136 | 841.571 | |

| 137 | 784.702 | |

| 138 | 776.376 | |

| 139 | 763.792 | |

| 140 | 748.052 | |

| 141 | 746.409 | |

| 142 | 745.348 | |

| 143 | 739.066 | |

| 144 | 738.634 | |

| 145 | 738.366 | |

| 146 | 737.979 | |

| 147 | 737.928 | |

| 148 | 737.167 | |

| 149 | 736.668 | |

| 150 | 736.605 | |

| 151 | 736.038 | |

| 152 | 735.975 | |

| 153 | 735.670 | |

| 154 | 735.205 | |

| 155 | 735.148 | |

| 156 | 734.677 | |

| 157 | 734.635 | |

| 158 | 734.221 | |

| 159 | 734.206 | |

| 160 | 733.968 | |

| 161 | 733.944 | |

| 162 | 733.904 | |

| 163 | 733.777 | |

| 164 | 733.615 | |

| 165 | 733.559 | |

| 166 | 732.777 | |

| 167 | 732.672 | |

| 168 | 732.305 | |

| 169 | 732.233 | |

| 170 | 731.743 | |

| 171 | 731.009 | |

| 172 | 730.976 | |

| 173 | 730.842 | |

| 174 | 730.154 | |

| 175 | 728.622 | |

| 176 | 726.357 | |

| 177 | 725.934 | |

| 178 | 725.772 | |

| 179 | 725.756 | |

| 180 | 724.539 | |

| 181 | 724.516 | |

| 182 | 724.126 | |

| 183 | 723.997 | |

| 184 | 723.945 | |

| 185 | 723.892 | |

| 186 | 723.667 | |

| 187 | 722.676 | |

| 188 | 721.798 | |

| 189 | 714.969 | |

| 190 | 632.054 | |

| 191 | 620.772 | |

| 192 | 531.252 |

See also

References

- "The scope and concerns of public health" (PDF). Oxford University Press: OUP.COM. March 5, 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 4, 2013. Retrieved December 3, 2010.

- World Health Organization. The world health report 2001 – Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope; 2001 [Retrieved 2008-10-19].

- Burden of Depressive Disorders by Country, Sex, Age, and Year: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010, Alize J. Ferrari, Fiona J. Charlson, Rosana E. Norman, Scott B. Patten, Greg Freedman, Christopher J.L. Murray, Theo Vos, Harvey A. Whiteford, Published: November 5, 2013 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001547

- Andrade L, Caraveo-A.. . Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 24 March 2006 [archived 23 November 2002];12(1):3–21. doi:10.1002/mpr.138. PMID 12830306.

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA. 2003;289(203):3095–105. doi:10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. PMID 12813115.

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. PMID 15939837.

- Murphy JM, Laird NM, Monson RR, Sobol AM, Leighton AH. A 40-year perspective on the prevalence of depression: The Stirling County Study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57(3):209–15. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.57.3.209. PMID 10711905.

- Gender differences in unipolar depression: An update of epidemiological findings and possible explanations. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2003;108(3):163–74. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.00204.x. PMID 12890270.

- Eaton WW, Anthony JC, Gallo J. Natural history of diagnostic interview schedule/DSM-IV major depression. The Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area follow-up. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54(11):993–99. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830230023003. PMID 9366655.

- Rickards H. Depression in neurological disorders: Parkinson's disease, multiple sclerosis, and stroke. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 2005;76:i48–i52. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2004.060426. PMID 15718222. PMC 1765679.

- Rotenstein, Lisa S.; Ramos, Marco A.; Torre, Matthew; Segal, J. Bradley; Peluso, Michael J.; Guille, Constance; Sen, Srijan; Mata, Douglas A. (2016-12-06). "Prevalence of Depression, Depressive Symptoms, and Suicidal Ideation Among Medical Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". JAMA. 316 (21): 2214–2236. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.17324. ISSN 1538-3598. PMC 5613659. PMID 27923088.

- Douglas A. Mata; Marco A. Ramos, Narinder Bansal, Rida Khan, Constance Guille, Emanuele Di Angelantonio & Srijan Sen (2015). "Prevalence of Depression and Depressive Symptoms Among Resident Physicians: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". JAMA. 314 (22): 2373–2383. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.15845. PMC 4866499. PMID 26647259.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Alboni P, Favaron E, Paparella N, Sciammarella M, Pedaci M. Is there an association between depression and cardiovascular mortality or sudden death?. Journal of cardiovascular medicine (Hagerstown, Md.). 2008;9(4):356–62. doi:10.2459/JCM.0b013e3282785240. PMID 18334889.

- Strik JJ, Honig A, Maes M. Depression and myocardial infarction: relationship between heart and mind. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 2001;25(4):879–92. doi:10.1016/S0278-5846(01)00150-6. PMID 11383983.

- Jorm AF. Does old age reduce the risk of anxiety and depression? A review of epidemiological studies across the adult life span. Psychological Medicine. 2000;30(1):11–22. doi:10.1017/S0033291799001452. PMID 10722172.

- Psychiatry, 4th edition - Oxford University Press, 2012 by By John Geddes, Jonathan Price, Rebecca McKnight page 222

- Stephanie A. Riolo; et al. (June 2005). "Prevalence of Depression by Race/Ethnicity: Findings From the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III". American Journal of Public Health. 95 (6): 998–1000. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2004.047225. PMC 1449298. PMID 15914823.

- Lopez, A. D.; Murray, C. C. (1998-11-01). "The global burden of disease, 1990-2020". Nature Medicine. 4 (11): 1241–1243. doi:10.1038/3218. ISSN 1078-8956. PMID 9809543.

- Wessel Skovlund, Charlotte (September 28, 2016). "Association of Hormonal Contraception With Depression". JAMA Psychiatry. 73 (11): 1154–1162. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.2387. PMID 27680324. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Age-standardized DALYs per 100,000 by cause, and Member State, 2004; 2004 [Retrieved 2011-03-31].