Ethnic groups in Pakistan

The major ethnic groups of Pakistan include Punjabis, Pashtuns, Sindhis, Saraikis, Muhajirs, Baloch, Paharis, Hindkowans, Rajputs, Mirpuri and other smaller groups. Smaller ethnic groups found throughout the nation include Kashmiris, Kalash, Chitralis, Siddi, Burkusho, Wakhis, Khowar, Hazara, Shina, Kalyu Baltis and Jatts.

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Pakistan |

|---|

|

| Traditions |

| Cuisine |

| Sport |

|

Pakistan's census does not include the 1.7 million refugees from Afghanistan[1] mainly found in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP), with significant populations in the cities of Karachi and Quetta. Most of these Afghan refugees were born in Pakistan within the last 30 years and are ethnic Pashtuns, Tajiks, Uzbeks, Baloch and Turkmen.[2]

Major ethnic groups

Punjabis

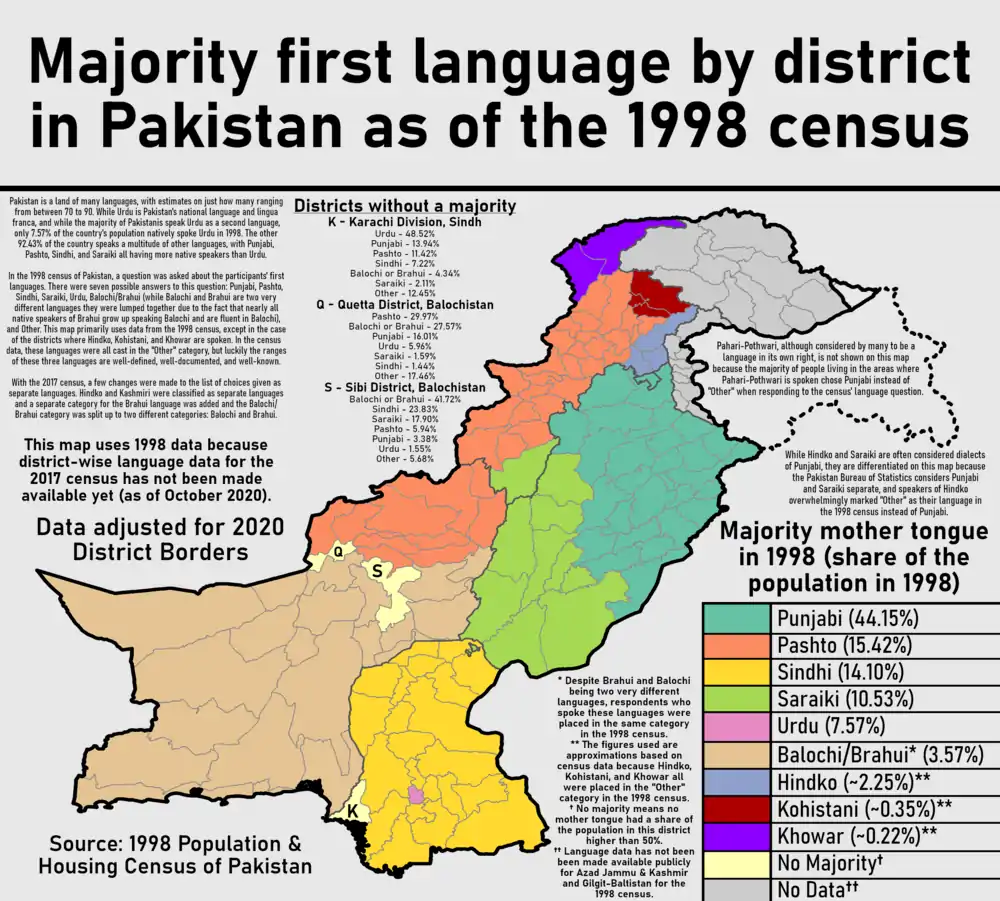

Punjabis are an Indo-Aryan ethno-linguistic group and they are the largest ethnic group in Pakistan by population, numbering approximately 110 million people and thus consisting of 50.0% of Pakistan's total population of 220 million in 2020. The Punjabis found in Pakistan belong to groups known as biradaris (literally 'brotherhood'), with further divisions between the zamindar or qoums, traditionally associated with agriculture, and moeens, traditionally associated with artisanry. Some zamindars are further divided into castes such as [(Rajpoot]), Jat, Shaikh, Khatri, Khandowa, Gujjar, Awan, Arain and Syed. Ethnicities from neighbouring regions such as Kashmiris, Pashtuns and Baluchis also form a sizeable portion of the population of Punjab, especially in metropolises such as Lahore, Rawalpindi, Sialkot and Faisalabad. A large number of Punjabis descend from groups historically associated with skilled professions and crafts, such as the Sunar, Lohar, Kumhar, Tarkhan, Julaha, Mochi, Hajjam, Chhimba Darzi, Teli, Lalari, Qassab, Mallaah, Dhobi, Mirasi, etc.[4][5][6] The Pakistani Punjab is relatively religiously homogenous, with 97% of the population adhering to Islam (with small Hindu, Sikh and Christian minorities). Notable Punjabi-Pakistanis include Nobel laureate Abdus Salam, cricketer Wasim Akram and economist Mahbub al Haq.

Pashtuns

Pashtuns (also referred to as Pukhtuns), an Iranic ethno-linguistic group, are Pakistan's second largest ethnicity (consisting 15% of the population). They are native to the region known as Pashtunistan, an area west of the Indus River including the provinces of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and northern Balochistan, southern and eastern Afghanistan.

They constitute a significant diaspora community in the cities of Lahore, Punjab and Karachi, Sindh and are also a major ethnic group among the 1.7 million Afghan refugees and asylum-seekers in Pakistan. Pashtuns are the ethnic Afghans, and are the majority group in Afghanistan. Pashtun are tribal people, with their own culture and values they follow (Pashtunwali)and a deep rich history linked to rulers.

They speak Pashto as their first language and are divided into multiple tribes such as Afridi and Yousafzai and Khattak, which are notably the main Pashtun tribes in Pakistan. They make up an estimated 35 million of Pakistan's total population[7][8] and are mostly adherent to Sunni Islam. Notable Pashtuns include former president Ayub Khan, incumbent prime minister Imran Khan, cricketers Shahid Afridi and Shaheen Afridi, actor Fawad Khan and Nobel Laureate Malala Yousafzai.

Sindhis

The Sindhis are an Indo-Aryan ethno-linguistic group who speak the Sindhi language and are native to the Sindh province of Pakistan and they are Pakistan's third largest ethnicity (consisting 14% of the country). Sindhis are predominantly Muslim. Sindhi Muslim culture is highly influenced by Sufi doctrines and principles and some of the popular cultural icons of Sindh are Shah Abdul Latif Bhitai, Lal Shahbaz Qalandar, Jhulelal and Sachal Sarmast.[9]

Saraikis

The Saraikis also known as Multanis,[10] are an ethnolinguistic group in central and southeastern Pakistan, primarily southern Punjab. Their language is Saraiki, which has similarities to Punjabi and Sindhi.

Muhajirs

Muhajirs (meaning "migrants") are also called "Urdu-speaking people." Muhajirs are a collective multiethnic group who emerged through the migration of Indian Muslims from various parts of India to Pakistan starting in 1947, as a result of the world's largest mass migration.[11][12] The majority of Muhajirs are settled in Sindh mainly in Karachi, Hyderabad, Sukkur and Mirpur Khas. Sizable communities of Muhajirs are also present in cities including Lahore, Multan, Islamabad, and Peshawar. Muhajirs held a dominating position during the early nation building years of Pakistan. Most Muslim politicians of the pre-independence era who supported the Pakistan movement were Urdu speakers. The term Muhajir is also used for descendants of Muslims who migrated to Pakistan after the 1947 partition of India.[6][13][14]

Baloch

The Baloch as an Iranic ethnic lingusitc group, are principally found in the east of Balochistan province of Pakistan.[15] Despite living south towards the Gulf of Oman and the Arabian sea for centuries, they are classified as a northwestern Iranian people in accordance to their language which belongs to the northwestern subgroup of Iranian languages.[16]

According to Dr. Akhtar Baloch, Professor at University of Karachi, the Balochis migrated from Balochistan during the Little Ice Age and settled in Sindh and Punjab. The Little Ice Age is conventionally defined as a period extending from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries[17][18][19] (or alternatively, from about 1300[20] to about 1850[21][22][23]), although climatologists and historians working with local records no longer expect to agree on either the start or end dates of this period, which varied according to local conditions. According to Professor Baloch, the climate of Balochistan was very cold and the region was uninhabitable during the winter so the Baloch people migrated in waves and settled in Sindh and Punjab.[24]

Kashmiris

Kashmiri are a Dardic (subgrouping of Indo-Aryan) ethnic group native to the Kashmir Valley and Azad Kashmir. The majority of Kashmiri Muslims are Sunni.[25] They refer to themselves as "Kashur" in their mother language. Kashmiri Muslims are descended from Kashmiri Hindus and are also known as 'Sheikhs'.[26][27][28][29] Presently, the Kashmiri Muslim population is predominantly found in Kashmir Valley. Smaller Kashmiri communities also live in other regions of the Jammu and Kashmir territory. One significant population of Kashmiris is in the Chenab valley region, which comprises the Doda, Ramban and Kishtwar districts of Jammu. There are also ethnic Kashmiri populations inhabiting Neelam Valley and Leepa Valley of Azad Kashmir. Since 1947, many ethnic Kashmiri Muslims also live in Pakistan.[30] Many ethnic Kashmiri Muslims from the Kashmir Valley also migrated to the Punjab region during Dogra and Sikh rule and adopted the Punjabi language. Surnames used by Kashmiris living in Punjab include Dar (Dhar), Butt (Bhat), lone, Mir, Khuwaja (a term used by converts just like sheikh), Wain (Wani), Sheikh (Saprus), etc. Kashmiri language, or Kashur, belongs to the Dardic group and is the most widely spoken Dardic language.[31][32]

Brahuis

The Brahui or Brahvi people are a Pakistani ethnic group of about 2.2 million people with the vast majority found in Balochistan, Pakistan. They are a small minority group in Afghanistan, where they are native, but they are also found through their diaspora in Middle Eastern states.[33] They mainly occupy the area in Balochistan from Bolan Pass through the Bolan Hills to Ras Muari (Cape Monze) on the Arabian sea, separating the Baloch people living to the east and west.[34][35] The Brahuis are almost entirely Sunni Muslims.[36]

Hindkowans

Hindkowans are a Hindko speaking people, they live mainly in the Hazara division and the Peshawar Division of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and there is also a large population of Hindkowans that can be found in the Pothohar Region of Punjab and Azad Kashmir in Pakistan. They have a population that consists of nearly four million people and they form 2% of Pakistan entire population.[8]

Hazara

The Hazara people, natives to the present day Hazarajat (Hazaristan), are a Persian-speaking people mostly residing in all Pakistan and specially in Quetta. Some are citizens of Pakistan while others are refugees. Genetically, the Hazara are a mixture of Turko-Mongols and Iranian-speaking peoples, and those of Middle East and Central Asia. The genetic research suggests that they are closely related to the Eurasian and the Uyghurs. The Pakistani Hazaras estimated population is believed to be more than 1,550,000.[37][38]

Burusho people

The Burusho or Brusho people live in the Hunza and Yasin valleys of Gilgit–Baltistan in northern Pakistan.[39] They are predominantly Muslims. Their language, Burushki, has not been shown to be related to any other language.[40] The Hunzakuts or Hunza people, are an ethnically Burusho people indigenous to the Hunza Valley, in the Karakorum Mountains of northern Pakistan. They are descended from inhabitants of the former principality of Hunza. The Hunza's are predominantly Shia Muslims, with many of them Ismaili.[41]

See also

References

- "UNHCR welcomes new government policy for Afghans in Pakistan". Pakistan: unhcrpk.org. 2016.

- "Voluntary Repatriation Update" (PDF). Pakistan: UNHCR. November 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-02-20. Retrieved 2017-11-26.

- The World Factbook

- Thorburn, S. S. (1983). Musalmans and Money Lenders in the Punjab ((reprint) ed.). New Delhi: Mittal Publications. ISBN 9789351137481.

- Mirza, Z.I., Hassan, M.U. and Bandaragoda, D.J., 1997. Socio-Economic Baseline Survey for a Pilot Project on Water Users Organizations in the Hakra 4-R Distributary Command Area, Punjab.

- Nazir, P., 1993. Social structure, ideology and language: caste among Muslims. Economic and Political Weekly, pp. 2897-2900.

- Livingston, Ian S. and Michael O'Hanlon (March 30, 2011). " Pakistan Index: Tracking Variables of Reconstruction & Security Archived July 14, 2014, at the Wayback Machine". Brookings Institution.

- The World Factbook

- "CIA Factbook Pakistan".

- Bhatia, Tej K.; Ritchie, William C. (2008-04-15). The Handbook of Bilingualism. John Wiley & Sons. p. 803. ISBN 9780470756744.

- "Rupture in South Asia" (PDF). UNHCR. Retrieved 2014-08-16.

- Dr Crispin Bates (2011-03-03). "The Hidden Story of Partition and its Legacies". BBC. Retrieved 2014-08-16.

- "Muhajirs in historical perspective". The Nation. 2014-11-07. Retrieved 2018-10-28.

- Paracha, Nadeem F. (2014-04-20). "The evolution of Mohajir politics and identity". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 2018-10-28.

- Blood, Peter, ed. "Baloch". Pakistan: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1995.

- "Balochi and the Concept of North-Western Iranian" (PDF). Agnes Korn. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2016-08-23.

- Mann, Michael (2003). "Little Ice Age". In Michael C MacCracken and John S Perry (ed.). Encyclopedia of Global Environmental Change, Volume 1, The Earth System: Physical and Chemical Dimensions of Global Environmental Change (PDF). John Wiley & Sons. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- Lamb, HH (1972). "The cold Little Ice Age climate of about 1550 to 1800". Climate: present, past and future. London: Methuen. p. 107. ISBN 0-416-11530-6. (noted in Grove 2004:4).

- "Earth observatory Glossary L-N". NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Green Belt MD: NASA. Retrieved 17 July 2015. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help). - Miller et al. 2012. "Abrupt onset of the Little Ice Age triggered by volcanism and sustained by sea-ice/ocean feedbacks" Geophysical Research Letters 39, 31 January: abstract (formerly on AGU website) (accessed via wayback machine 11 July 2015); see press release on AGU website (accessed 11 July 2015).

- Grove, J.M., Little Ice Ages: Ancient and Modern, Routledge, London (2 volumes) 2004.

- Matthews, J.A. and Briffa, K.R., "The 'Little Ice Age': re-evaluation of an evolving concept", Geogr. Ann., 87, A (1), pp. 17–36 (2005). Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- "1.4.3 Solar Variability and the Total Solar Irradiance - AR4 WGI Chapter 1: Historical Overview of Climate Change Science". Ipcc.ch. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- From Zardaris to Makranis: How the Baloch came to Sindh

- Snedden, Christopher (2015). Understanding Kashmir and Kashmiris. Oxford University Press. p. 7. ISBN 9781849046220.

As in Pakistan, Sunni Muslims comprise the majority population of Kashmir, whereas they are a minority in Jammu, while almost all Muslims in Ladakh are Shias.

- Census of India, 1941. Volume XXII. p. 9. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

The Muslims living in the southern part of the Kashmir Province are of the same stock as the Kashmiri Pandit community and are usually designated Kashmiri Muslims; those of the Muzaffarabad District are partly Kashmiri Muslims, partly Gujjar and the rest are of the same stock as the tribes of the neighbouring Punjab and North \Vest Frontier Province districts.

- Kashmiri Pandits: Looking to the Future. APH Publishing. 2001. ISBN 9788176482363.

The Kashmiri Pandits are the precursors of Kashmiri Muslims who now form a majority in the valley of Kashmir...Whereas Kashmiri Pandits are of the same ethnic stock as the Kashmiri Muslims, both sharing their habitat, language, dress, food and other habits, Kashmiri Pandits form a constituent part of the Hindu society of India on the religious plane.

- Bhasin, M.K.; Nag, Shampa (2002). "A Demographic Profile of the People of Jammu and Kashmir" (PDF). Journal of Human Ecology. Kamla-Raj Enterprises: 15. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

Thus the two population groups, Kashmiri Pandits and Kashmiri Muslims though at the time constituted ethnically homogenous population, came to differ from each other in faith and customs.

- Bhasin, M.K.; Nag, Shampa (2002). "A Demographic Profile of the People of Jammu and Kashmir" (PDF). Journal of Human Ecology: 16. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

The Sheikhs are considered to be the descendants of Hindus and the pure Kashmiri Muslims, professing Sunni faith, the major part of the population of Srinagar district and the Kashmir state.

- Snedden, Christopher (2015). Understanding Kashmir and Kashmiris. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9781849046220.

Small numbers of ethnic Kashmiris also live in other parts of J&K. There are Kashmiris who live in areas that border the Kashmir Valley, including Kishtwar (Kishtawar), Bhadarwah, Doda and Ramban, in Jammu in Indian J&K, and in the Neelum and Leepa Valleys of northern Azad Kashmir. Since 1947, many ethnic Kashmiris and their descendants also can be found in Pakistan. Invariably, Kashmiris in Azad Kashmir and Pakistan are Muslims.

- "Introduction".

- "Introduction".

- James B. Minahan (30 August 2012). "Brahuis". Ethnic Groups of South Asia and the Pacific: An Encyclopedia. ISBN 9781598846607. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- Shah, Mahmood Ali (1992), Sardari, jirga & local government systems in Balochistan, Qasim Printers, pp. 6–7

- Minahan, James B. (31 August 2016), "Brahui", Encyclopedia of Stateless Nations: Ethnic and National Groups around the World, 2nd Edition: Ethnic and National Groups around the World, ABC-CLIO, pp. 79–80, ISBN 978-1-61069-954-9

- Dictionary of Languages: The Definitive Reference to More Than 400 Languages. Columbia University Press. 2004-03-01. ISBN 9780231115698. Retrieved 2010-09-09.

- Malik Ayub Sumbal. "The Plight of the Hazaras in Pakistan". thediplomat.com. The Diplomat. Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- "Who are the Hazara?". tribune.com.pk. The Express Tribune. 5 October 2011. Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- "Jammu and Kashmir Burushaski : Language, Language Contact, and Change" (PDF). Repositories.lib.utexas.edu. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "Burushaski language". Encyclopædia Britannica online.

- Ghoash, Palash (1 February 2014). "Hunza: A Paradise Of High Literacy And Gender Equality In A Remote Corner Of Pakistan". International Business Times. Retrieved 31 July 2016.