Growth of religion

Growth of religion is the spread of religions and the increase of religious adherents around the world. Statistics commonly measure the absolute number of adherents, the percentage of the absolute growth per year, and the growth of the number of converts in the world. Such forecasts cannot be validated empirically and remain contentious.

Studies in the 21st century suggest that, in terms of percentage and worldwide spread,[1][2] Islam is the fastest-growing major religion in the world.[3] A comprehensive religious forecast for 2050 by the Pew Research Center concludes that global Muslim population is expected to grow at a faster rate than the Christian population due primarily to the young age and high fertility-rate of Muslims.[4][5] Counting the number of converts to a religion is difficult, because some national censuses ask people about their religion, but they do not ask if they have converted to their present faith, and In some countries, legal and social consequences make conversion difficult, such as death sentence of leaving Islam in some Muslim countries.[6][7][8][9][10] Statistical data on conversion to and from Islam are scarce.[11] According to study published on 2011 by Pew Research, what little information is available suggests that religious conversion has no net impact on the Muslim population as the number of people who convert to Islam is roughly similar to those who leave Islam.[12][13][11] According to another study published on 2015 by Pew research center, Islam is expected to experience a modest gain of 3 million adherents through religious conversion between 2010 and 2050, although this modest impact, this will make Islam, compared with other religions, the second largest religion in terms of net gains through religious conversion after religiously unaffiliated, which expected has the largest net gains through religious conversion.[14]

Some religions proselytise vigorously (Christianity and Islam, for example), others (such as Judaism) do not generally encourage conversions into their ranks. Some faiths grow exponentially at first, only for their zeal to wane (note the case of Zoroastrianism). The growth of a religion can clash with factors such as persecution, entrenched rival religions (such as established religions), and religious market saturation.[15]

Growth of religious groups

Baháʼí Faith

The World Christian Encyclopedia estimated only 7.1 million Baháʼís in the world in 2000, representing 218 countries,[16] and its evolution to the World Christian Database (WCD) estimated 7.3 million in 2010.[17] The WCD stated: "The Baha'i [sic] Faith is the only religion to have grown faster in every United Nations region over the past 100 years than the general population; Baha'i [sic] was thus the fastest-growing religion between 1910 and 2010, growing at least twice as fast as the population of almost every UN region."[18] 2015's estimate is of 7.8 million Baháʼís in the world.[19] Margit Warburg, a Danish researcher, has argued that this source contains numerical inaccuracies in its statistics on the Baháʼí Faith.[20]

From its origins in the Persian and Ottoman empires of the 19th century the Baháʼí Faith was able to gain converts elsewhere in Asia, Europe, and North America by the early 20th century. John Esslemont performed the first review of the worldwide progress of the religion in 1919.[21] 'Abdu'l-Bahá, son of the founder of the religion, then set goals for the community through his Tablets of the Divine Plan shortly before his death. Shoghi Effendi then initiated systematic Baháʼí pioneering efforts that brought the religion to almost every country and territory of the world and converts from more than 2,000 tribes and peoples. There were serious setbacks in the Soviet Union[22][23] where Baháʼí communities in 38 cities across Soviet territories ceased to exist. However plans continued building to 1953 when the Baháʼís initiated a Ten Year Crusade after plans had focused on Latin America and Europe after WWII. That last stage was largely towards parts of Africa.[24][25][26] Due to extensive missionary work, wide-scale growth in the religion across Sub-Saharan Africa particularly was observed to begin in the 1950s and extend in the 1960s.[27] There was diplomatic pressure from northern Arab countries against this development that was eventually overcome.[28] Starting in the 1980s with Perestroyka the Baháʼís began to re-organize across the Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc. While sometimes failing to meet official minimums for recognitions as a religion, communities of Baháʼís do exist from Poland to Mongolia. The worldwide progress was such that the Encyclopædia Britannica (2002) identified the religion as the second-most geographically widespread religion after Christianity.[29] It has established Baháʼí Houses of Worship by continental region and been the object of interest and support of diverse non-Baháʼí notable people from Leo Tolstoy[30] to Khalil Gibran[31] to Mohandas K. Gandhi[32] to Desmond Tutu.[33] See List of Baháʼís for a list of notable Baháʼís.

ARDA/WCD statistics place the Baháʼí Faith as currently the largest religious minority in Iran[34] (despite significant persecution and the overall Iranian diaspora), Panama,[35] and Belize;[36] the second largest international religion in Bolivia,[37] Zambia,[38] and Papua New Guinea;[39] and the third largest international religion in Chad[40] and Kenya.[41] In 2014 the religion was officially recognized in Indonesia[42] and in addition to various countries it is the second largest religion in state of South Carolina – a fact that, despite its small size, got some attention in 2014.[43][44] Based on data from 2010, Baháʼís were the largest minority religion in 80 counties out of the 3143 counties in the United States.[45] The countries with the fastest annual growth from 2000 to 2015 per annum, where a country has over 100,000 people, were, (starting with the fastest): Qatar, UAE, Bahrain, Oman, Kuwait, Kazakhstan, Western Sahara, South Sudan, and Niger, ranging from 3.90% growth per year up to 9.56%.[19]

A Baháʼí published survey reported 4.74 million Baháʼís in 1987.[46] Baháʼí sources since 1991 usually estimate the worldwide Baháʼí population at "above 5 million".[47][48]

Buddhism

Buddhism is based on the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama, commonly known as the Buddha, who born in modern day Nepal and lived and taught in northeastern India in the 5th century BC. The majority of Buddhists live in Asia; Europe and North America also have populations exceeding 1 million.[50] According to scholars of religious demographics, there are between 488 million,[51] 495 million,[52] and 535 million[53] Buddhists in the world. According to Johnson and Grim, Buddhism has grown from a total of 138 million adherents in 1910, of which 137 million were in Asia, to 495 million in 2010, of which 487 million are in Asia.[52] According to them, there was a fast annual growth of Buddhism in Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Lebanon and several Western European countries (1910–2010). More recently (2000–2010), the countries with highest growth rates are Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, and some African countries.[54] The Australian Bureau of Statistics, through statistical analysis, held Buddhism to be the fastest-growing spiritual tradition in Australia in terms of percentage gain, with a growth of 79.1% for the period 1996 to 2001 (200,000→358,000).[49]

And according to a 2012 Pew Research Center survey, over the next four decades the number of Buddhists around the world is expected to decrease from 487 million in 2010 to 486 million in 2050.[55] The decline is due to several factors such as the low fertility level among Buddhists (1.6 children per woman),[56] and the old age (median age of 34), compared to the overall population.[57] According to the Pew Research Center published on 2010, religious conversion may have little impact on the Buddhists population between 2010 and 2050; Buddhists are expected to lose 2.9 million adherents between 2010 and 2050.[14]

According to a 2017 Pew Research Center survey, between 2010 and 2015 "an estimated 32 million babies were born to Buddhist mothers and roughly 20 million Buddhists died, meaning that the natural increase in the Buddhists population – i.e., the number of births minus the number of deaths – was 12 million over this period".[58] According to the same study Buddhists "are projected to decline in absolute number, dropping 7% from nearly 500 million in 2015 to 462 million in 2060. Low fertility rates and aging populations in countries such as China, Thailand and Japan are the main demographic reasons for the expected shrinkage in the Buddhist population in the years ahead".[58]

Chinese traditional religion

According to a survey of religion in China in the year 2010, the number of people practicing some form of Chinese folk religion is near to 950 million (70% of the Chinese),[59] of which 173 million (13%) practice some form of Taoist-defined folk faith.[59] Further in detail, 12 million people have passed some formal initiation into Taoism, or adhere to the official Chinese Taoist Association.[59] Comparing this with other surveys, evidence suggests that nowadays three-fifths to four-fifths of the Chinese believe in folk religion.[60] This shows a significant growth from the 300–400 million people practicing Chinese traditional religion that were estimated in the 1990s and early 2000s.[61][62]

This growth reverses the rapid decline that Chinese traditional religion faced in the 20th century.[63] Moreover, Chinese religion has also spread throughout the world following the emigration of Chinese populations, with 672,000 adherents in Canada as of 2010.[63]

According to scholars Miikka Ruokanen and Paulos Huang, the rebirth of Chinese traditional religion in China is faster and larger than the spread of other religions in the country, such as Buddhism and Christianity:[64]

Since the 1980s, with the gradual opening of society, folk religion has begun to recover. Especially in the rural areas, the speed and scale of its development are much faster and larger than is the case with Buddhism and Christianity [...] in Zhejiang province, where Christianity is better established than elsewhere, temples of folk religion are usually twenty or even a hundred times as numerous as Christian church buildings.

The number of adherents of the Chinese traditional religion is difficult to count, because of :[65]

Chinese rarely use the term "religion" for their popular religious practices, and they also do not utilize a vocabulary that they "believe in" gods or truths. Instead, they engage in religious acts that assume a vast array of gods and spirits and that also assume the efficacy of these beings in intervening in this world.[66]

The Chinese folk religion is a "diffused religion" rather than "institutional".[65] It is a meaning system of social solidarity and identity, ranging from the kinship systems to the community, the state, and the economy, that serves to integrate Chinese culture.[65]

Christianity

According to a 2011 Pew Research Center survey, there are 2.2 billion Christians around the world in 2010,[67] up from about 600 million in 1910.[67] And according to a 2012 Pew Research Center survey, within the next four decades, Christians will remain the world's largest religion; if current trends continue, by 2050 the number of Christians will reach 2.9 billion (or 31.4%).[69] According to a 2017 Pew Research Center survey, by 2060 Christians will remain the world's largest religion; and the number of Christians will reach 3.05 billion (or 31.8%).[58]

By 2050, the Christian population is expected to exceed 3 billion.[70] Christians have 2.7 children per woman, which is above replacement level (2.1).[71] According to Pew Research Center study, by 2050 the number of Christians in absolute number is expected to grow to more than double in the next few decades,[72] from 517 million to 1.1 billion in Sub Saharan Africa,[72] from 531 million to 665 million in Latin America and Caribbean,[72] from 287 million to 381 million in Asia,[72] and from 266 million to 287 million in North America.[72] By 2050, Christianity is expected to remain the majority of population and the largest religious group in Latin America and Caribbean (89%),[73] North America (66%),[74] Europe (65.2%)[75] and Sub Saharan Africa (59%).[70]

Europe was the home for the world's largest Christian population for the past 1,000 years, since 2015 Christians in Africa and Latin America respectively surpass Europe Christian population.[58] in 2018 a new data from the Gordon Theological Seminary shows that, for the first time ever, more number of Christians live in Africa than on any other single continent:[76] "The results show Africa on top with 631 million Christian residents, Latin America in 2nd place with 601 million Christians, and Europe in 3rd place with 571 million Christians".[77] In 2017 Christianity added nearly 50 million people due to factors such as birth rate and religious conversion.[77] According to a 2017 Pew Research Center survey, between 2010 and 2015 "an estimated 223 million babies were born to Christian mothers and roughly 107 million Christians died, meaning that the natural increase in the Christian population – i.e., the number of births minus the number of deaths – was 116 million over this period".[58] Religious conversions is projected to have a "modest impact on changes in the religious groups including Christian population" between 2010 and 2050;[78] and may negatively affect the growth of Christian population and it's share of the world’s populations "slightly",[78] however, "the largest net loses through religious conversion is expected among Christians" between 2010 and 2050.[78]

According to Mark Jürgensmeyer of the University of California, popular Protestantism is one of the most dynamic religious movements in the contemporary world.[79] Changes in worldwide Protestantism over the last century have been significant.[80][81][82][83] Since 1900, due primarily to conversion, Protestantism has spread rapidly in Africa, Asia, Oceania and Latin America.[84] That caused Protestantism to be called a primarily non-Western religion.[81][83] Much of the growth has occurred after World War II, when decolonization of Africa and abolition of various restrictions against Protestants in Latin American countries occurred.[82] According to one source, Protestants constituted respectively 2.5%, 2%, 0.5% of Latin Americans, Africans and Asians.[82] In 2000, percentage of Protestants on mentioned continents was 17%, more than 27% and 5.5%, respectively.[82]

The significant growth of Christianity in non-Western countries led to regional distribution changes of Christians.[70] In 1900, Europe and the Americas were home to the vast majority of the world's Christians (93%). Besides, Christianity has grown enormously in Sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, and the Pacific.[70] In 2010, 26% of the world's Christians lived in Europe, followed by 24.4% in Latin America and the Caribbean, 23.8% in Sub-Saharan Africa, 13.2% in Asia and the Pacific, 12.3% in North America, and 1% in the Middle East and North Africa.[85] The study also suggested that by 2050, the global Christian population will change considerably. By 2050, 38% of the world's Christians will live in the Sub-Saharan Africa, followed by 23% in Latin America and the Caribbean, 16% in Europe, 13% in Asia and the Pacific and 10% of the world's Christians will live in North America .[86]

In mid-2005 Christianity adds about 65.1 million people annually due to factors such as birth rate and religious conversion, while losing 27.4 million people annually due to factors such as death rate and religious apostasy. Most of the net growth in the numbers of Christians is in Africa, Latin America and Asia.[87]

Christianity is still the largest religion in Western Europe, according to a 2018 study by the Pew Research Center, 71.0% of the Western European population identified themselves as Christians.[88] According to the same study, a large majority of those who raised as Christians (83%) in Western Europe, still identified themselves as Christians today.[88] On the other hand, Central and Eastern European countries did not experience a decline in the percentage of Christians, as the proportion of Christians in these countries have mostly been stable or even increasing.[89]

According to a 2005 paper submitted to a meeting of the American Political Science Association, most of Christianity's growth has occurred in non-Western countries. The paper concludes that the Pentecostalism movement is the fastest-growing religion worldwide.[91] Protestantism is growing as a result of historic missionary activity and indigenous Christian movements by Africans in Africa,[92][93] and due primarily to conversion in Asia,[90][93][94][95] Latin America,[93][96][97] Muslim world,[98] and Oceania.[83]

The US Department of State estimated in 2005 that Protestants in Vietnam may have grown by 600% over the previous 10 years.[99] In South Korea, Christianity has grown from 2.0% in 1945[90] to 20.7% in 1985 and to 29.3% in 2010,[67] And the Catholic Church has increased its membership by 70% in the last ten years.[100] In Singapore, the percentage of Christians among Singaporeans increased from 12.7%, in 1990, to 17.5%, in 2010.[101] In recent years, the number of Chinese Christians has increased significantly; Christians were 4 million before 1949 (3 million Catholics and 1 million Protestants), and are reaching 67 million today,[67][68] Christianity is reportedly the fastest growing religion in China with average annual rate of 7%.[102] Some reports also show that many of the Chinese Indonesians minority convert to Christianity,[103][104] Demographer Aris Ananta reported in 2008 that "anecdotal evidence suggests that more Buddhist Chinese have become Christians as they increased their standards of education".[105] According to a poll conducted by the Gallup Organization in 2006, Christianity has increased significantly in Japan, particularly among youth, and a high number of teens are becoming Christians.[106] In Iran, Christianity is reportedly the fastest growing religion with an average annual rate of 5.2%.[107]

In 1900, there were only 8.7 million[67] adherents of Christianity in Africa, while in 2010 there were 390 million.[67] It is expected that by 2025 there will be 600 million Christians in Africa.[67] In Nigeria, the percentage of Christians has grown from 21.4%, in 1953, to 50.8%, in 2010.[67] In South Africa, Pentecostalism has grown from 0.2%, in 1951, to 7.6%, in 2001.[108] According to Pew Research Center the number of Catholics in Africa has increased from one million in 1901 to 329,882,000 in 2010.[67] From 2015 to 2016, Africa saw an increase of more than 6,265,000 Catholics.[109]

Catholic Church membership in 2013 was 1.254 billion, which is 17.7% of the world population, an increase from 437 million, in 1950[110] and 654 million, in 1970.[111] The main growth areas have been Asia and Africa, 39% and 32%, respectively, since 2000.

Since 2010, the rate of increase was of 0.3% in the Americas and Europe.[112] On the other hand, Eric Kaufman, of University of London, argued that the main reason for the expansion of Catholicism and conservative Protestantism along with other religions is because their religions tend to be "pro-natal" and they have more children, and not due to religious conversion.[113]

Protestantism is one of the most dynamic religious movements in the contemporary world.[79] From 1960 to 2000, the global growth of the number of reported Evangelicals grew three times the world's population rate, and twice that of Islam.[114] Evangelical Christian denominations also are among the fastest-growing denominations in some Catholic Christian countries, such as Brazil and France (France jumping from 2% to 3% of the population).[115][116][117] In Brazil, the total number of Protestants jumped from 16.2% in 2000[118] to 22.2% in 2010 (for the first time, the percentage of Catholics in Brazil is less than 70%). These cases don't contribute to a growth of Christianity overall, but rather to a substitution of a brand of Christianity with another one.

According to the records of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, its membership has grown every decade since its beginning in the 1830s,[119] that it is among the top ten largest Christian denominations in the U.S.,[120] and that it was the fastest growing church in the U.S. in 2012.[121]

According to the World Christian Encyclopedia[122] estimate significantly more people have converted to Christianity from Islam in the 21st century than at any other point in Islamic history.[123] According to "2015 Believers in Christ from a Muslim Background": A Global Census study estimates 10.2 million Muslims converted to Christianity[lower-alpha 1] can be found in Afghanistan,[124] Albania,[125] Azerbaijan,[126][127] Algeria,[128][129] Belgium,[130] Bulgaria,[131][132] France,[133] Germany,[134] Indonesia,[135] Iran,[136][137][138][139] Kazakhstan,[140] Kyrgyzstan,[141] Malaysia,[142] Morocco,[143][144] Netherlands,[145] Russia,[146] Saudi Arabia,[147] Tunisia,[148] Turkey,[149][150][151][152] Kosovo,[153] the United States,[154] and Central Asia.[155][156] According to reports there been a wave of Muslims who converting to Christianity in Europe since 2016.[157][158][159] The 19th century saw at least 250,000 Jews convert to Christianity according to existing records of various societies.[160] Data from the Pew Research Center has it that, as of 2013, about 1.6 million adult American Jews identify themselves as Christians, most as Protestants.[161][162][163] According to the same data, most of the Jews who identify themselves as some sort of Christian (1.6 million) were raised as Jews or are Jews by ancestry.[162] According to a 2012 study, 17% of Jews in Russia identify themselves as Christians.[164][165]

While according to a Pew Research Center survey it is expected that from 2010 to 2050 a significant number of Christians will leave their faith.[166] Most of the switching are expected into the unaffiliated and Irreligion.[167] According to pew research center, religious conversion may negatively affect the growth of Christians by 72 million between 2015 and 2060, most of the switching are expected into the unaffiliated and Irreligion.[168] The scenario is missing reliable data of the religious switching in China; however, the study suggest that the average annual rate of Christian growth in China is around 7%.[78] Large increases in the developing world (around 23,000 per day) have been accompanied by substantial declines in the developed world, mainly in Europe and North America.[169] According to scholar John D. Martin at Baylor University, the statements of the decline of Christianity in Europe are "greatly exaggerated", and that there are increasing signs of a Christian revival in Europe.[170] According to scholar Filip Mazurczak at George Washington University Christianity is recovering Spain,[171] and revivaling in Hungary, Croatia and elsewhere in Eastern Europe.[172] By 2050, Christianity is expected to remain the majority in the United States (66.4%, down from 78.3% in 2010), and the number of Christians in absolute number is expected to grow from 243 million to 262 million.[173] According to Pew Research Center, Christianity is declining in the United states while non-Christian faiths are growing.[174][175][176][177][178][179][180][181] According to Pew Research Center, the number of those leaving Christianity in the United States is greater than the number of converts; however, the number of those convert to evangelical Christianity in the United States is greater than the number of those leaving that faith.[182] While on the other hand, in 2017, scholars Landon Schnabel and Sean Bock at Harvard University and Indiana University argued that while "Mainline Protestant" churchs has declined in the United States since the late 1980s, but many of them do not leave Christianity, but rather convert to another Christian denomination, in particularly to evangelicalism, Schnabel and Bock argued also that evangelicalism and Conservative Christianity has persisted and expanded in the United States.[183] And according to Eric Kaufmann from Harvard University and University of London, Christian fundamentalism is expanding in the United States.[184]

According to study published by the Christian missionary David B. Barrett,[185] and professor of global Christianity, George Thomas Kurian,[186] and both are work on World Christian Encyclopedia, approximately 2.7 million converting to Christianity annually from another religion, World Christian Encyclopedia also cited that Christianity rank at first place in net gains through religious conversion.[187] On the other hand, demographer Conrad Hackett of Pew Research Center stated that the World Christian Encyclopedia gives a higher estimate for percent Christian when compared to other cross-national data sets.[188] While according to book "The Oxford Handbook of Religious Conversion", which written by professor of Christian mission, Charles E. Farhadian,[189] and professor of psychology, Lewis Rambo,[190] in mid-2005 approximately 15.5 million convert to Christianity annually from another religion, while approximately 11.7 million leave Christianity, most of them become irreligious, resulting in a net gain of 3.8 million.[87]

According to scholar Philip Jenkins Christianity is growing rapidly in China and some other Asian countries and sub-Saharan Africa.[191] According to a study by a scholar Fenggang Yang from Purdue University, Christianity is "spreading among the Chinese of South-East Asia", and "Evangelical and Pentecostal Christianity is growing more quickly in Asia",[192] also according to him, many of the recent converts are young and educated.[192] According to a report by the Singapore Management University, more people in Southeast Asia are converting to Christianity, and these new converts are mostly ethnic Chinese and have a university degree.[193] According to scholar Juliette Koning and Heidi Dahles of Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam there is a "rapid expansion of charismatic Christianity from the 1980s onwards. Singapore, China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Indonesia, and Malaysia are said to have the fastest-growing Christian communities and the majority of the new believers are “upwardly mobile, urban, middle-class Chinese”. Asia has the second largest Pentecostal-charismatic Christians of any continent, with the number growing from 10 million to 135 million between 1970 and 2000".[193] According to scholar Terence Chong, since 1980s Christianity is expanding in Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia, Taiwan, and South Korea.[194] According to Xi Lian, professor of Christianity at Duke University “there has indeed been an explosive growth in Christianity, particularly in Protestants” in China.[195] Some Scholars and expert assessments suggest that conversions to Christianity is rising and growing rapidly in China.[192] According to scholar Wang Zuoa, 500,000 Chinese converts to Protestantism annually.[196] According to the Council on Foreign Relations the "number of Chinese Protestants has grown by an average of 10 percent annually since 1979".[197] According to scholar Todd Hartch at Eastern Kentucky University, by 2005, around 6 million Africans converted to Christianity annually.[198] Reports suggest that Christianity is growing rapidly in Iran,[199][200][201] and among Iranian diaspora.[202]

It's been reported also that increasing numbers of young people are becoming Christians in several countries.[106][203] It's been also reported that conversion into Christianity is significantly increasing among Korean,[204] Chinese,[205] and Japanese in the United States.[206] By 2012 percentage of Christians on mentioned communities was 71%, more than 30% and 37%,[207] respectively. In 2010 there were approximately 180,000 Arab Americans and about 130,000 Iranian Americans who converted from Islam to Christianity (however most Arab Americans are Arab Christians[208] who trace their heritage back to the early Christian communities). Scholar Dudley Woodberry form Fuller Theological Seminary estimated approximately that 20,000 Muslims convert to Christianity annually in the United States.[209] According to the World Christian Encyclopedia, between 1965 and 1985 about 2.5 million Indonesian converted from Islam to Christianity.[122] Many people who convert to Christianity face persecution.[210]

According to the historian Geoffrey Blainey from the University of Melbourne, since the 1960s there has been a substantial increase in the number of conversions from Islam to Christianity, mostly to the Evangelical and Pentecostal forms.[214] According to Blainey, this is due to several reasons, including the lack of ties of Evangelical Christianity with colonial powers in contrast to Roman Catholic Church and Mainline Protestant Churches, as well as the rising of Islamism, which lead some Muslims to look towards other religions such as Christianity through evangelical activity in the visual and audio media, as well as irreligion.[215] Many Muslims who convert to Christianity face social and governmental persecution.[216] Scholar David Radford from the University of South Australia estimated that "between 8 and 10 million former Muslims have converted to Christianity in the past two decades",[217] and according to Radford the largest Christian of Muslim background communities can be found in Indonesia, Nigeria, the United States, Ethiopia, Algeria, and Iran.[218] Indonesia is home to the largest Christian community of Muslim background in the world; according to various sources, since the mid and late 1960s, between two million to 3 million Muslims converted to Christianity.[219][220][211][221][212][213] According to scholars Felix Wilfred from the University of Madras and Chris Hann from the University of Cambridge and Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, since the fall of communism, the number of Muslim converts to Christianity in Adjara,[222] Azerbaijan, Balkans and Central Asian republics has been rapidly increased.[223][224] According to scholar Michael Bourdeaux from the Keston Institute, since the fall of communism, the number of Muslim converts to Christianity in Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Caucasus, Kosovo, Central Asian republics and Russia has increased;[225] Scholar John Garrard and Carol Garrard from the Princeton University cited that while most of Russian Christians who converted to Islam are primarily women who converted upon their marriage with a Muslim spouse, on the other hand, Muslims who convert to Christianity in Russia are coming from various ethnic groups, ages, gender, and socio-economic situations.[226] Some scholars indicate that in the Middle East in the past two decades there been increasing numbers of conversions to Christianity among the Berbers, Kurds, Persians, and Turks, and among some religious minorites such as Alawites and Druze.[227][228][229][230][231] According to some scholars there have been an increasing number of conversions to Christianity among Muslim minorites in the Western world in the past decades, most noticeably by Afghans, Albanians, Iranians, Iraqis, Maghrebis, Kurds, Turks, but also by Arabs as well as Indians and Pakistanis.[232][233][234][235][236] On the other hand, according to Guinness, approximately 12.5 million more people converted to Islam than converts to Christianity between 1990-2000.[237]

Deism

The 2001 American Religious Identification Survey (ARIS) survey estimated that between 1990 and 2001 the number of self-identifying deists grew from 6,000 to 49,000, representing about 0.02% of the US population at the time.[238]

Druze

The Druze are an Arabic-speaking esoteric ethnoreligious group;[241] the number of Druze people worldwide is between 800,000 and one million, with the vast majority residing in the Levant.[242] Even though the faith originally developed out of Ismaili Islam, the Druze do not identify as Muslims.[243][244] The Druze faith do not accept converts to their faith, nor practice proselytism.[245] On the other hand; over the centuries a number of the Druze embraced Christianity,[246][247][248][249] Islam and other religions.

The Druze reside primarily in Syria, Lebanon, Israel and Jordan.[250] Syria is home to the largest Druze community in the world, according to a study published by Columbia University, the number of Syrian Druze increased from 684,000 in 2010 to 730,000 in mid of 2018.[251] The Lebanese Druze have the lowest fertility among all age groups after the Lebanese Christians.[252]

According to the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics in 2017, the Israeli Druze population growth rate of 1.4%, which is lower than the Muslim population growth rate (2.5%) and the total population growth (1.7%), but higher than the Arab Christian population growth rate (1.0%). At the end of 2017, the average age of the Israeli Druze was 27.9.[253] About 26.3% of the Israeli Druze population are under 14 years old and about 6.1% of the Israeli Druze are 65 years and over. Since the year 2000, the Israeli Drue community has witnessed a significant decrease in fertility-rate and a significant increase in life expectancy.[254] The fertility rate for Israeli Druze in 2017 is 2.1 children per woman, while the fertility rate among Jewish women (3.2) and Muslim women (3.4) and the fertility rate among Israeli Christian women (1.9).[255]

Hinduism

Hinduism is the third largest religion in the world.[256] Hindu beliefs are vast and diverse, and thus Hinduism is often referred to as a family of religions rather than a single religion.[257] Within each religion in this family of religions, there are different theologies, practices, and sacred texts. This diversity has led to an array of descriptions for Hinduism. It has been described as henotheism,[258] polytheism, panentheism,[259] and monotheism.[260] Hinduism is one of the oldest living religions in the world. Hindus made up about 15% of the population in 2010, when there were 1 billion Hindus in the world.[261] According to Pew Research Center 99% of Hindus live in the Indo-Pacific region in 2010. According to Pew Forum, Hindus are anticipated to continue to be concentrated primarily in the Indo-Pacific region in 2050. Hinduism is the largest religion in the countries of India and Nepal.[262] Approximately 94% of the world's Hindus live in India.[263] 79.80% of India's population is Hindu, accounting for about 90% of Hindus worldwide. Hinduism's 10-year growth rate is estimated at 20% (based on the period 1991 to 2001), corresponding to a yearly growth close to 2%.[264][265] According to a 2017 Pew Research Center survey, between 2010 and 2015 "an estimated 109 million babies were born to Hindu mothers and roughly 42 million Hindus died, meaning that the natural increase in the Hindus population – i.e., the number of births minus the number of deaths – was 42 million over this period".[58]

Like other religious traditions present during the time period of the classical era, Hinduism flourished under various empires which supported the religion. Rulers sponsored Hindu temples and art, while also supporting other religious communities. Of note is the Khmer Empire, which extended over large parts of Southeast Asia. During the reign of Suryavarman II, Vaishnavism spread throughout the empire. The famous Angkor Wat temple in Cambodia was commissioned during this time.[266]

Hinduism is a growing religion in countries such as Ghana,[267] Russia,[268] and the United States.[269][270] According to 2011 census, Hinduism has become the fastest-growing religion in Australia since 2006[271] due to migration from India and Fiji.[272]

Hinduism is the fastest-growing religion in Ireland, predominantly a Christian country. The country's Hindu population grew 34 percent in five years, according to the Ireland census, conducted in April 2016 by its Central Statistics Office (CSO) and released on April 6, 2017. In contrast, the overall population growth in Ireland was 3.8 percent.[273]

Generally, the term "conversion" is not applicable to Hindu traditions. According to Arvind Sharma, Hinduism "is typically quite comfortable with multiple religious participation, multiple religious affiliations, and even with multiple religious identities."[274]

India, a country that holds the majority of the world's Hindu's is also home to state-level Freedom of Religion Acts to regulate non-voluntary conversion.[275]

Islam

Modern growth

In 1990, 1.1 billion people were Muslims, while in 2010, 1.6 billion people were Muslims.[276][277] According to the BBC, a comprehensive American study concluded in 2009 that the number of Muslims worldwide stood at about 23% of the world's population with 60% of the world's Muslims living in Asia.[278] According to the same study "globally, Muslims have the highest fertility rate, an average of 3.1 children per woman – well above replacement level (2.1)", and "in all major regions where there is a sizable Muslim population, Muslim fertility exceeds non-Muslim fertility".[279] From 1990 to 2010, the global Muslim population increased at an average annual rate of 2.2%. By 2030 Muslims are projected to represent about 26.4% of the global population (out of a total of 7.9 billion people).[3] "Although the religion began in Arabia, by 2002 80% of all believers in Islam lived outside the Arab world".

On the other hand, in 2010, the Pew Forum found "that statistical data for Muslim conversions is scarce and as per their little available information, there is no substantial net gain or loss of Muslims due to religious conversion. It also stated that "the number of people who embrace Islam and the number of those who leave Islam are roughly equal. Thus, this report excludes religious conversion as a direct factor from the projection of Muslim population growth."[280] People switching their religions will likely have no effect on the growth of the Muslim population,[13] as the number of people who convert to Islam is roughly similar to those who leave Islam.[12] Another study found that the number of people who will leave Islam is 9,400,000 and the number of converts to Islam is 12,620,000 so the net gain to Islam through conversion should be 3 million between 2010 and 2050, mostly from Sub Saharan Africa (2.9 million).[14] The growth of Islam from 2010 to 2020 has been estimated at 1.70%[3] due to high birthrates in Asia, the Middle East, and Europe. The report also shows that the fall in the birth rate of Muslims slowed down the growth rate from 1990 to 2010. It is due to the fall of the fertility rate in many Muslim majority countries. Despite the decline, Muslims still have the highest birth rate among the world's major religious groups.[281][282] According to the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, the World Christian Database as of 2007 has Islam as the fastest-growing religion in the world.[283] A 2007 Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) report argued that some Muslim population projections are overestimated, as they assume that all descendants of Muslims will become Muslims even in cases of mixed parenthood.[284]

According to a 2017 Pew Research Center survey, between 2010 and 2015 "an estimated 213 million babies were born to Muslim mothers and roughly 61 million Muslims died, meaning that the natural increase in the Muslim population – i.e., the number of births minus the number of deaths – was 152 million over this period",[58] and it added small net gains through religious conversion into Islam (420,000). According to a 2017 Pew Research Center survey, by 2060 Muslims will remain the second world's largest religion; and if current trends continue, the number of Muslims will reach 2.9 billion (or 31.1%).[58]

It was reported in 2013 that around 5,000 British people convert to Islam every year, with most of them being women.[285] According to an earlier 2001 census, surveys found that there was an increase of 60,000 conversions to Islam in the United Kingdom.[286] Many converts to Islam said that they suffered from hostility from their families.[286] According to a report by CNN, "Islam has drawn converts from all walks of life, most notably African-Americans".[287] Studies estimated about 30,000 converting to Islam annually in the United States.[288] According to The New York Times, an estimated 25% of American Muslims are converts,[289] these converts are mostly African American.[290] According to The Huffington Post, "observers estimate that as many as 20,000 Americans convert to Islam annually.", most of them are women and African-Americans.[291] experts say that conversions to Islam have doubled in the past 25 years in France, among the six million Muslims in France, about 100,000 are converts.[292] The Norwegian newspaper reported that there is an increase in the number of converts to Islam, and also reported that there are about 3,000 people who converted to Islam in recent years.[293] On the other hand, according to Pew Research, the number of American converts to Islam is roughly equal to the number of American Muslims who leave Islam and this is unlike other religions in the United States where the number of those who leave these religions is greater than the number of those who convert to it,[294] and most people who leave Islam become unaffiliated, according to same study ex-Muslims were more likely to be Christians compare to ex-Hindus or ex-Jews.[294]

Resurgent Islam is one of the most dynamic religious movements in the contemporary world.[79] The Vatican's 2008 yearbook of statistics revealed that for the first time, Islam has outnumbered the Roman Catholics globally. It stated that, "Islam has overtaken Roman Catholicism as the biggest single religious denomination in the world",[295][296] and stated that, "It is true that while Muslim families, as is well known, continue to make a lot of children, Christian ones on the contrary tend to have fewer and fewer".[297] According to the Foreign Policy, High birth rates were cited as the reason for the Muslim population growth.[298] With 3.1 children per woman, Muslims have higher fertility levels than the world's overall population between 2010 and 2015. High fertility is a major driver of projected Muslim population growth around the world and in particular regions.[299] Between 2010 and 2015, with exception of the Middle East and North Africa, Muslim fertility of any other region in the world was higher than the rate for the region as a whole.[299] While Muslim birth rates are expected to experience a decline, it will remain above replacement level and higher fertility than the world's overall by 2050.[300] As per U.N.'s global population forecasts, as well as the Pew Research projections, over time fertility rates generally converge toward the replacement level.[300] Globally, Muslims were younger (median age of 23) than the overall population (median age of 28) as of 2010.[301] While decline of Muslim birth rates in coming years have also been well documented.[302][303][304] According to David Ignatius, there is major decline in Muslim fertility rates as pointed out by Nicholas Eberstadt. Based on the data from 49 Muslim-majority countries and territories, he found that Muslims birth rate has significantly dropped for 41% between 1975 and 1980 to 2005–10 while the global population decline was 33% during that period. It also stated that over a 50% decline was found in 22 Muslim countries and over a 60% decline in Iran, Oman, the United Arab Emirates, Algeria, Bangladesh, Tunisia, Libya, Albania, Qatar and Kuwait.[305]

According to the religious forecast for 2050 by Pew Research Center, between 2010 and 2050 modest net gains through religious conversion are expected for Muslims (3 million)[307] and most of the net gains through religious conversion for Muslims found in the Sub Saharan Africa (2.9 million).[14] The study also reveals that, due to young age & relatively high fertility rate among Muslims by 2050 there will be near parity between Muslims (2.8 billion, or 30% of the population) and Christians (2.9 billion, or 31%), possibly for the first time in history.[308] While both religions will grow but Muslim population will exceed the Christian population and by 2100, Muslim population (35%) will be 1% more than the Christian population (34%).[309] By the end of 2100 Muslims are expected to outnumber Christians.[310] According to the same study, Muslims population growth is twice of world's overall population growth due to young age and relatively high fertility rate and as a result Muslims are projected to rise to 30% (2050) of the world's population from 23% (2010).[311]

While the total Fertility Rate of Muslims in North America is 2.7 children per woman in the 2010 to 2015 period, well above the regional average (2.0) and the replacement level (2.1).[312] Europe's Muslim population also has higher fertility (2.1) than other religious groups in the region, well above the regional average (1.6).[299] A new study of Population Reference Bureau by demographers Charles Westoff and Tomas Frejka suggests that the fertility gap between Muslims and non-Muslims is shrinking and although the Muslim immigrants do have more children than other Europeans their fertility tends to decline over time, often faster than among non-Muslims.[313]

Generally, there are few reports about how many people leave Islam in Muslim majority countries. The main reason for this is the social and legal repercussions associated with leaving Islam in many Muslim majority countries, up to and including the death penalty for apostasy.[314] On the other hand the increasingly large ex-Muslim communities in the Western world that adhere to no religion have been well documented.[315] A 2007 Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) report argued that some Muslim population projections are overestimated, as they assume that all descendants of Muslims will become Muslims even in cases of mixed parenthood.[284][316] Equally, Darren E. Sherkat questioned in Foreign Affairs whether some of the Muslim growth projections are accurate as they do not take into account the increasing number of non-religious Muslims. Quantitative research is lacking, but he believes the European trend mirrors the American: data from the General Social Survey in the United States show that 32 percent of those raised Muslim no longer embrace Islam in adulthood, and 18 percent hold no religious identification.[316] Many Muslims who leave Islam face social rejection or imprisonment and sometimes murder or other penalties.[316] According to Harvard University professor Robert D. Putnam, there is increasing numbers of Americans who are leaving their faith and becoming unaffiliated and the average Iranian American is slightly less religious than the average American.[181] According to Public Affairs Alliance of Iranian Americans, the number of Iranian Americans Muslims decreased from 42% in 2008 to 31% in 2012 according to a telephone survey around the Los Angeles region.[180] A June 2020 online survey found a much smaller percentage of Iranians stating they believe in Islam, with half of those surveyed indicating they had lost their religious faith.[201] The poll, conducted by the Netherlands-based GAMAAN (Group for Analyzing and Measuring Attitudes in Iran), using online polling to provide greater anonymity for respondents, surveyed 50,000 Iranians and found 32% identified as Shia, 5% as Sunni and 3% as Shia Sufi Muslim (Irfan Garoh).[201][200][lower-alpha 2] A survey conducted by Pew Research Center in 2017 found that conversion has a negative impact on the growth of the Muslim population in Europe, with roughly 160,000 more people leaving Islam than converting into Islam between 2010 and 2016.[317]

By 2010 an estimated 44 million Muslims were living in Europe (6%), up from 4.1% in 1990. By 2030, Muslims are expected to make up 8% of Europe's population including an estimated 19 million in the EU (3.8%),[318] including 13 million foreign-born Muslim immigrants.[319] Islam is widely considered as the fastest growing religion in Europe due primarily to immigration and above average birth rates.[318][320][321] Between 2010 and 2015 the Muslim fertility rate in Europe was (2.1). On the other hand, the fertility rate in Europe as a whole was (1.6).[321] Pew study also reveals that Muslims are younger than other Europeans. In 2010, the median age of Muslims throughout Europe was (32), eight years younger than the median for all Europeans (40).[319] According to a religious forecast for 2050 by Pew Research Center conversion does not add significantly to the growth of the Muslim population in Europe,[322] according to the same study the net loss is (−60,000) due to religious switching.[323]

The Pew Research Center notes that "the data that we have isn't pointing in the direction of 'Eurabia' at all",[324] and predicts that the percentage of Muslims is estimated to rise to 8% in 2030, due to immigration and above-average birth rates. And only two western European countries – France and Belgium – will become around 10 percent Muslim, by 2030. According to Justin Vaïsse the fertility rate of Muslim immigrants declines with integration.[325] He further points out that Muslims are not a monolithic or cohesive group,[326] Most academics who have analysed the demographics dismiss the predictions that the EU will have Muslim majorities.[327] It is completely reasonable to assume that the overall Muslim population in Europe will increase, and Muslim citizens have and will have a significant impact on European life.[328] The prospect of a homogenous Muslim community per se, or a Muslim majority in Europe is however out of the question.[329] Eric Kaufman of University of London denied the claims of Eurabia. According to him, Muslims will be a significant minority rather than majority in Europe and as per their projections for 2050 in the Western Europe, there will be 10–15 per cent Muslim population in high immigration countries such as Germany, France and the UK.[330] Eric Kaufman also argue that the main reason why Islam is expanding along with other religions, is not because of conversion to Islam, but primarily to the nature of the religion, as he calls it "pro-natal", where Muslims tend to have more children.[113] Doug Saunders states that by 2030 Muslims and Non-Muslims birth rates will be equal in Germany, Greece, Spain and Denmark without taking account of the Muslims immigration to these countries. He also states that Muslims & Non-Muslims fertility rate difference will decrease from 0.7 to 0.4 and this different will continue to shrink as a result of which Muslims and non-Muslims fertility rate will be identical by 2050.[331] A survey conducted by Pew Research Center in 2017 found that conversion has a negative impact on the growth of the Muslim population in Europe, with roughly 160,000 more people leaving Islam than converting into Islam between 2010 and 2016.[317]

It is often reported from various sources, including the German domestic intelligence service (Bundesnachrichtendienst), that Salafism is the fastest-growing Islamic movement in the world.[332][333][334][335] According to the World Christian Encyclopedia, the fastest-growing denomination in Islam is Ahmadiyya Muslim Community with a growth rate of 3.25%.[336] Most other sects have a growth rate of less than 3%.[337]

In 2010 Asia was home for (62%) of the world's Muslims, and about (20%) of the world's Muslims lived in the Middle East and North Africa, (16%) in Sub Saharan Africa, and 2% in Europe.[339] By 2050 Asia will home for (52.8%) of the world's Muslims, and about (24.3%) of the world's Muslims will live in Sub Saharan Africa, (20%) the Middle East and North Africa, and 2% in Europe. As per the Pew Research study, Muslim populations will grow in absolute number in all regions of the world between 2010 and 2050. The Muslim population in the Asia-Pacific region is expected to reach nearly 1.5 billion by 2050, up from roughly 1 billion in 2010. The growth of Muslims is also expected in the Middle East-North Africa region, It is projected to increase from about 300 million in 2010 to more than 550 million in 2050. Besides, the Muslim population in sub-Saharan Africa is forecast to grow from about 250 million in 2010 to nearly 670 million in 2050 which is more than double. The absolute number of Muslims is also expected to increase in regions with smaller Muslim populations such as Europe and North America,[340] due to young age & relatively high fertility rate.[308] In Europe Muslim population will be nearly double (from 5.9% to 10.2%).[340] In North America, it will grow 1% to 2%.[340] In Asia Pacific region, Muslims will surpass the Hindus by the time. In Latin America and Caribbean Muslim population will stay 0.1% by 2050.[341]

In 2010 Indonesia, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Nigeria was home for (47.8%) of the world's Muslims.[338] Currently India is home for one of the largest Muslim population, by 2050 India is projected to have the world's largest Muslim population (around 301.6 million Muslim) followed by Pakistan, Indonesia, Nigeria and Bangladesh, and expected to be home for (46%) of the world's Muslims.[338]

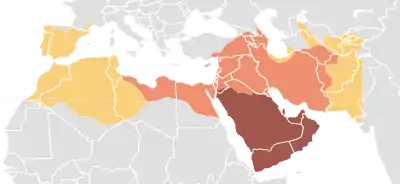

Historical growth within the Middle East

There exist different views among scholars about the spread of Islam. Islam began in Arabia and from 633 AD until the late 10th century it was spread through conquests, far-reaching trade and missionary activity.[342][343]

According to Rodney Stark, Islam was spread after military conquests after Arab armies began overtaking Christian regions from Syria to North Africa and Spain,[344] as well as Zoroastrian, Buddhist and Hindu regions in Central Asia, parts of South Asia and Southeast Asia via military invasions,[345][346][347] traders and Sufi missionaries.[342][348][349][350] According to some scholars, the Jizya (poll tax) was the most important factor in the mass conversion to Islam, the tax paid by all non-Muslims (Dhimmis – which translated means "protected persons") in Islamic empires[351][352][353][354] While other scholars oppose this belief, because the jizya was not of great value, and those who could not pay it were exempt from it.[355][356][357] (such as Christians under the Ottoman Empire's authority,[358][359] Hindus and Buddhists under regime of Muslim invaders,[349] Coptic Christians under administration of the Muslim Arabs,[352] Zoroastrians living under Islamic rule in ancient Persia,[360] and also with Jewish communities in the medieval Arab world[354]) while some scholars indicate that some Muslim rulers in India did not consistently collect the jizya (poll tax) from Dhimmis.[349] Under Islamic law, Muslims are required to pay Zakat, one of the five pillars of Islam. Muslims take 2.5% out of their salaries and use the funds give to the needy.[361] since non-Muslims are not required to pay Zakat, they instead had to pay Jizya if they wanted the same protections the Muslims received.[362] In India, Islam was brought by various traders and rulers from Afghanistan and other places. According to other scholars, many converted for a whole host of reasons, the main statement of which was evangelization by Muslims, though there were several instances where some were pressured to convert owing to internal violence and friction between the Christian and Muslim communities, according to historian Philip Jenkins.[363] However John L. Esposito, a scholar on the subject of Islam in The Oxford History of Islam states that the spread of Islam "was often peaceful and sometimes even received favorably by Christians".[364] In a 2008 conference on religion at Yale University's The MacMillan Center Initiative on Religion, Politics, and Society which hosted a speech from Hugh Kennedy, he stated forced conversions played little part in the history of the spread of the faith.[365] However, the poll tax known as Jizyah may have played a part in converting people over to Islam but as Britannica notes "The rate of taxation and methods of collection varied greatly from province to province and were greatly influenced by local pre-Islamic customs" and there were even cases when Muslims had the tax levied against them, on top of Zakat.[366] Hugh Kennedy has also discussed the Jizyah issue and stated that Muslim governments discouraged conversion but were unable to prevent it.[367]

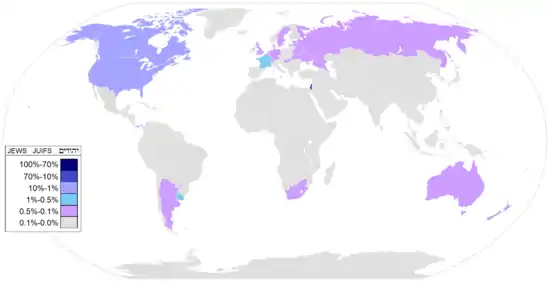

Judaism

Today, the majority of the world's Jewish population is concentrated in two countries, the United States and Israel.[369] Israel is the only country with a Jewish population that is consistently growing through natural population growth, although the Jewish populations of other countries, in Europe and North America, have recently increased through immigration. In the Diaspora, in almost every country the Jewish population in general is either declining or steady, but Orthodox and Haredi Jewish communities, whose members often shun birth control for religious reasons, have experienced rapid population growth.[370]

Orthodox and Conservative Judaism discourage proselytism to non-Jews,[371] but many Jewish groups have tried to reach out to the assimilated Jewish communities of the Diaspora in order for them to reconnect to their Jewish roots.[372] Additionally, while in principle Reform Judaism favors seeking new members for the faith, this position has not translated into active proselytism, instead of taking the form of an effort to reach out to non-Jewish spouses of intermarried couples.[373] Studies have shown that Haredi Jews population is rising rapidly due to the young age and very high fertility-rate,[374] especially in Israel.[375]

The overall growth rate of Jews in Israel is 1.7% annually.[376] The diaspora countries, by contrast, have low Jewish birth rates, an increasingly elderly age composition, and a negative balance of people leaving Judaism versus those joining.[377]

There is also a trend of Orthodox movements reaching out to secular Jews in order to give them a stronger Jewish identity so there is less chance of intermarriage.[372] As a result of the efforts by these and other Jewish groups over the past 25 years, there has been a trend (known as the Baal teshuva movement) for secular Jews to become more religiously observant, though the demographic implications of the trend are unknown.[378] Additionally, there is also a growing rate of conversion to Jews by Choice of gentiles who make the decision to head in the direction of becoming Jews.[379]

Rates of interreligious marriage vary widely: In the United States, it is just under 50 percent,[380] in the United Kingdom, around 53 percent; in France; around 30 percent,[381] and in Australia and Mexico, as low as 10 percent.[382][383] In the United States, only about a third of children from intermarriages affiliate with Jewish religious practice.[384] The result is that most countries in the Diaspora have steady or slightly declining religiously Jewish populations as Jews continue to assimilate into the countries in which they live.[385]

In 1939, the core Jewish population reached its historical peak of 17 million (0.8% of the global population). Because of the Holocaust, the number had been reduced to 11 million by the end of 1945.[386] The population grew again to around 13 million by the 1970s, but has since recorded near-zero growth until around 2005 due to low fertility rates and to assimilation.[387] Since 2005, the world's Jewish population has been growing modestly at a rate of around 0.78% (in 2013). This increase primarily reflects the rapid growth of Haredi and some Orthodox sectors, who are becoming a growing proportion of Jews.[368]

According to the Pew Research Center published on 2010, religious conversion may have little impact on the Jewish population between 2010 and 2050; Jews are expected to lose 0.3 million adherents, between 2010 and 2050.[14] According to a 2017 Pew Research Center survey, between 2010 and 2015 "an estimated one million babies were born to Jewish mothers and roughly 600,000 Jewish died, meaning that the natural increase in the Jewish population – i.e., the number of births minus the number of deaths – was 500,000 million over this period".[58] according to the same study, over the next four decades the number of Jews around the world is expected to increase from 14.2 million in 2015 to 16.3 million in 2060.[58]

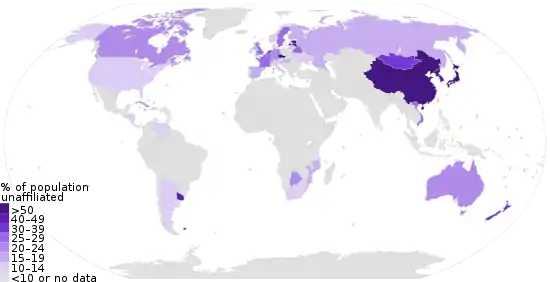

Nonreligious

In terms of absolute numbers, irreligion appears to be increasing (along with secularization generally).[388] (See the geographic distribution of atheism.)

According to Pew Research Center survey in 2012, religiously unaffiliated (include agnostic and atheist) make up about 18.2% of Europe's population,[390] and they make up the majority of the population in only two European countries: Czech Republic (76%) and Estonia (60%).[390] According to a 2017 Pew Research Center survey, between 2010 and 2015 "an estimated 68 million babies were born to religiously unaffiliated mothers and roughly 42 million religiously unaffiliated died, meaning that the natural increase in the religiously unaffiliated population – i.e., the number of births minus the number of deaths – was 26 million over this period".[58] As for religious conversion, the religiously unaffiliated is expected to have the largest net gains through religious conversion between 2010 and 2050, notably on Europe and Americas. However, religiously unaffiliated is expected to grow slightly due to a decrease in the fertility rate among the religiously unaffiliated population.[14]

The American Religious Identification Survey gave nonreligious groups the largest gain in terms of absolute numbers: 14.3 million (8.4% of the population) to 29.4 million (14.1% of the population) for the period 1990–2001 in the U.S.[391][392] A 2012 study by the Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life reports, "The number of Americans who do not identify with any religion continues to grow at a rapid pace. One-fifth of the U.S. public – and a third of adults under 30 – are religiously unaffiliated today, the highest percentages ever in Pew Research Center polling."[393]

A similar pattern has been found in other countries such as Australia, Canada, and Mexico. According to statistics in Canada, the number of "Nones" increased by about 60% between 1985 and 2004.[394] In Australia, census data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics give "no religion" the largest gains in absolute numbers over the 15 years from 1991 to 2006, from 2,948,888 (18.2% of the population that answered the question) to 3,706,555 (21.0% of the population that answered the question).[395] According to INEGI, in Mexico, the number of atheists grows annually by 5.2%, while the number of Catholics grows by 1.7%.[396][397] In New Zealand, 39% of the population are irreligious, making it the country with the largest irreligious population percentage in the Oceania region.[398]

According to a religious forecast for 2050 by Pew Research Center, the percentage of the world's population that unaffiliated or nonreligious is expected to drop, from 16% of the world's total population in 2010 to 13% in 2050.[399] The decline is largely due to the advanced age (median age of 34) and low fertility among unaffiliated or Nonreligious (1.7 children per woman in the 2010–2015 period). Sociologist Phil Zuckerman's global studies on atheism have indicated that global atheism may be in decline due to irreligious countries having the lowest birth rates in the world and religious countries having higher birth rates in general.[400]

According to Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life, by 2050 unaffiliated or nonreligious are expected to account for 27% of North America total population (up from 17.1% as in 2010), and 23% of Europe total population (up from 18% as in 2010).[401] The religiously unaffiliated are stationed largely in the Asia-Pacific region, where 76% resided in that regione in 2010, and is expected to be 68% by 2050. The share of the global unaffiliated population living in Europe is projected to grow from 12% in 2010 to 13% in 2050. The proportion of the global religiously unaffiliated living in North America will rise from 5% in 2010, to 9% in 2050.[401] According to the Pew Research Center, religious conversion may have modest impact on religiously unaffiliated population between 2010 and 2050; religiously unaffiliated are expected to gain 61 million adherents. The largest net movement is expected to be into religiously unaffiliated category between 2010 and 2050.[14]

Sikhism

.jpg.webp)

Sikhism or Gurmat was founded by Guru Nanak in the 15th century.[402] The religion began in the region of Punjab in eastern Pakistan and Northwest India.[403] Today, India is home to the largest Sikh population 2% of its population, or about 20 million people identifying as Sikh.[404] Within India, a majority of Sikhs live in the state of Punjab.[405] Outside of India, the largest Sikh communities are in the United Kingdom (at about 300,000 members), the United States (at about 120,000 members), and Canada (at about 200,000 members).[403] By 2050, according to Pew research center based on growth rate of current Sikh population between (2001-2011), India will have 27,129,086 Sikhs by half-century which will more then that of any country including the Western world.[406]

Wicca

The American Religious Identification Survey gives Wicca an average annual growth of 143% for the period 1990 to 2001 (from 8,000 to 134,000 – U.S. data / similar for Canada & Australia).[391][392] According to The Statesman Anne Elizabeth Wynn claims "The two most recent American Religious Identification Surveys declare Wicca, one form of paganism, as the fastest growing spiritual identification in America".[407][408] Mary Jones claims Wicca is one of the fastest-growing religions in the United States as well.[409] Wicca, which is largely a "Pagan" religion primarily attracts followers of nature-based religions in, as an example, the Southeast Valley region of the Phoenix, Arizona metropolitan area.[410]

Zoroastrianism

Zoroastrianism was founded during the early Persian Empire in the 6th century BCE by Zarathustra.[412] It served as the state religion of the ancient Iranian empires for more than a millennium, from around 600 BCE to 650 CE, but declined from the 7th century onwards following the Muslim conquest of Persia of 633–654.[413] Zoroastrianism declined as forced conversion increased with the rise of Islam.[414][415] From the 10th century onwards,[416] Zoroastrians emigrated to Gujarat, India where they found asylum from unjust persecutions and since then are called Parsi, since Indians called Persia Faras and hence named them Parsi.[417] Recent estimates place the current number of Zoroastrians at around 110,000–120,000,[418] at most with the majority living in India, Iran, and North America; their number has been thought to be declining.[419][411]

India has the world's largest Zoroastrian population. According to the 2011 Census of India, there are 57,264 Parsis in India.[420][421] According to the National Commission for Minorities, there are a "variety of causes that are responsible for this steady decline in the population of the community", the most significant of which were childlessness and migration-[422] Demographic trends project that by the year 2020 the Parsis will number only 23,000. The Parsis will then cease to be called a community and will be labeled a 'tribe'.[423] One-fifth of the decrease in population is attributed to migration.[424] A slower birthrate than deathrate accounts for the rest: as of 2001, Parsis over the age of 60 make up for 31% of the community. Only 4.7% of the Parsi community are under 6 years of age, which translates to 7 births per year per 1,000 individuals.[425] Concerns have been raised in recent years over the rapidly declining population of the Parsi community in India.[426]

There has been recent conversions of Kurds from Islam to Zoroastrianism in Kurdistan for different reasons, including a sense of national and/or ethnic identity or for recent conflicts with radical Muslims, which had been enthusiastically received by Zoroastrians worldwide.[427][428][429]

The number of Kurdish Zoroastrians, along with those of non-ethnic converts, has been estimated differently.[430] The Zoroastrian Representative of the Kurdistan Regional Government in Iraq has claimed that as many as 100,000 people in Iraqi Kurdistan have converted to Zoroastrianism recently, with community leaders repeating this claim and speculating that even more Zoroastrians in the region are practicing their faith secretly.[431][432][433] However, this has not been confirmed by independent sources.[434]

Overall statistics

Data collection

Statistics on religious adherence are difficult to gather and often contradictory; statistics for the change of religious adherence are even more so, requiring multiple surveys separated by many years using the same data gathering rules. This has only been achieved in rare cases, and then only for particular countries, such as the American Religious Identification Survey[391] in the United States, or census data from Australia (which has included a voluntary religious question since 1911).[435]

Historical growth

The World Religion Database[436] (WRD) is a peer-reviewed database of international religious statistics based on research conducted at the Institute on Culture, Religion & World Affairs at Boston University. It is published by Brill and is the most comprehensive database of religious demographics available to scholars, providing data for all of the world's countries.[437] Adherence data is largely compiled from census and surveys.[438] The database groups adherents into 18 broadly-defined categories: Agnostics, Atheists,[lower-alpha 3] Baháʼís, Buddhists, Chinese folk-religionists, Christians, Confucianists, Daoists, Ethnoreligionists, Hindus, Jains, Jews, Muslims, New Religionists, Shintoists, Sikhs, Spiritists, and Zoroastrians. The WRD is edited by demographers Todd M. Johnson[439] and Brian J. Grim.[440]

| Religion | 1900 | 1910 | 1970 | 2000 | 2010 | Rate* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adherents | % | Adherents | % | Adherents | % | Adherents | % | Adherents | % | 1910–2010 | 2000–2010 | |

| Christians | 558,345,962 | 34.47 | 611,810,000 | 34.8 | 1,229,308,840 | 33.22 | 1,988,966,546 | 32.37 | 2,260,440,000 | 32.8 | 1.32 | 1.31 |

| Muslims | 200,301,122 | 12.37 | 221,749,000 | 12.6 | 570,566,719 | 15.42 | 1,291,279,826 | 21.01 | 1,553,773,000 | 22.5 | 1.97 | 1.86 |

| Hindus | 202,976,290 | 12.53 | 223,383,000 | 12.7 | 462,981,539 | 12.51 | 822,396,657 | 13.38 | 948,575,000 | 13.8 | 1.46 | 1.41 |

| Agnostics | 3,028,450 | 0.19 | 3,369,000 | 0.2 | 544,299,664 | 14.71 | 656,409,731 | 10.68 | 676,944,000 | 9.8 | 5.45 | 0.32 |

| Buddhists | 126,946,371 | 7.84 | 138,064,000 | 7.9 | 234,956,867 | 6.35 | 452,301,190 | 7.36 | 494,881,000 | 7.2 | 1.28 | 0.99 |

| Chinese folk | 379,974,110 | 23.46 | 390,504,000 | 22.2 | 238,026,581 | 6.43 | 431,243,766 | 7.02 | 436,258,000 | 6.3 | 0.11 | 0.16 |

| Ethnic Religion | 117,312,635 | 7.24 | 135,074,000 | 7.7 | 169,417,360 | 4.58 | 224,054,933 | 3.65 | 242,516,000 | 3.5 | 0.59 | 1.06 |

| Atheists | 226,220 | 0.01 | 243,000 | 0 | 165,156,380 | 4.46 | 141,022,510 | 2.29 | 136,652,000 | 2.0 | 6.54 | 0.05 |

| New religion | 5,985,985 | 0.37 | 6,865,000 | 0.4 | 39,557,298 | 1.07 | 62,942,743 | 1.02 | 63,004,000 | 0.9 | 2.24 | 0.29 |

| Sikhs | 2,962,000 | 0.18 | 3,232,000 | 0.2 | 10,668,200 | 0.29 | 19,973,000 | 0.33 | 23,927,000 | 0.3 | 2.02 | 1.54 |

| Spiritists | 268,540 | 0.02 | 324,000 | 0 | 4,657,760 | 0.13 | 12,544,478 | 0.20 | 13,700,000 | 0.2 | 3.82 | 0.94 |

| Jews | 11,725,410 | 0.72 | 13,193,000 | 0.8 | 13,901,778 | 0.38 | 12,880,910 | 0.21 | 17,064,000 | 0.2 | 0.11 | 1.02 |

| Daoists | 375,000 | 0.02 | 437,000 | 0 | 1,734,000 | 0.05 | 7,132,555 | 0.12 | 8,429,000 | 0.1 | 3.00 | 1.73 |

| Confucianists | 840,000 | 0.05 | 760,000 | 0 | 5,759,150 | 0.16 | 7,995,470 | 0.13 | 6,449,000 | 0.1 | 2.16 | 0.36 |

| Baháʼí Faith | 204,535 | 0.01 | 225,000 | 0 | 2,657,336 | 0.07 | 6,051,749 | 0.10 | 7,306,000 | 0.1 | 3.54 | 1.72 |

| Jains | 1,323,780 | 0.08 | 1,446,000 | 0.1 | 2,628,510 | 0.07 | 4,792,953 | 0.08 | 5,316,000 | 0.1 | 1.31 | 1.53 |

| Shinto | 6,720,000 | 0.41 | 7,613,000 | 0.4 | 4,175,000 | 0.11 | 2,831,486 | 0.05 | 2,761,000 | 0.0 | −1.01 | 0.09 |

| Zoroastrians | 108,590 | 0.01 | 98,000 | 0 | 124,669 | 0.00 | 186,492 | 0.00 | 192,000 | 0.0 | 0.51 | 0.74 |

| Total Population: | 1,619,625,000 | 100.0 |

1,758,412,000 | 100.0 |

3,700,577,651 | 100.0 |

6,145,008,995 | 100.0 |

6,895,889,000 | 100.0 |

1.38 |

1.20 |

| *Rate = average annual growth rate, percent per year indicated

Source: Todd M. Johnson and Brian J. Grim[441] | ||||||||||||

Future change

Projections of future religious adherence are based on assumptions that trends, total fertility rates, life expectancy, political climate, conversion rates, secularization, etc will continue. Such forecasts cannot be validated empirically and are contentious, but are useful for comparison.[1][2] Professor Eric Kaufmann, whose academic specialization is how demography affects irreligion/religion/politics, wrote in 2012:

In my book, Shall the Religious Inherit the Earth?: Demography and Politics in the Twenty-First Century, I argue that 97% of the world's population growth is taking place in the developing world, where 95% of people are religious. On the other hand, the secular West and East Asia has very low fertility and a rapidly aging population. The demographic disparity between the religious, growing global South and the aging, secular global North will peak around 2050. In the coming decades, the developed world's demand for workers to pay its pensions and work in its service sector will soar alongside the booming supply of young people in the third world. Ergo, we can expect significant immigration to the secular West which will import religious revival on the back of ethnic change. In addition, those with religious beliefs tend to have higher birth rates than the secular population, with fundamentalists having far larger families. The epicentre of these trends will be in immigration gateway cities like New York (a third white), Amsterdam (half Dutch), Los Angeles (28% white), and London, 45% white British.[442]

Future change by conversion

According to the Pew Research Center published in 2010, religious conversion may have little impact on religious demographics between 2010 and 2050. Christianity is expected to lose a net of 66 million adherents mostly to religiously unaffiliated, while religiously unaffiliated are expected to gain 61 million adherents. Islam is expected to gain 3.2 million followers, while Buddhists and Jews are expected to lose 2.9 million and 0.3 million adherents, respectively.[14]

| Religion | Switching in | Switching out | Net change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Religiously Unaffiliated | 97,080,000 | 35,590,000 | +61,490,000 |

| Islam | 12,620,000 | 9,400,000 | +3,220,000 |

| folk religions | 5,460,000 | 2,850,000 | +2,610,000 |

| Other religions | 3,040,000 | 1,160,000 | +1,880,000 |

| Hinduism | 260,000 | 250,000 | +10,000 |

| Judaism | 320,000 | 630,000 | –310,000 |

| Buddhism | 3,370,000 | 6,210,000 | –2,850,000 |

| Christianity | 40,060,000 | 106,110,000 | –66,050,000 |

The largest net gains for the religiously unaffiliated between 2010 and 2050 are expected in North America (+26 million), Europe (+24 million), Latin America (+6 million), and the Asia-Pacific region (4 million). Islam is projected to have a net gain of followers in Sub-Saharan Africa (+2.9 million) and Asia-Pacific (+0.95 million), but net loss of followers in North America (-0.58 million) and Europe (-0.06 million). Christianity is expected to have the largest net loss of followers between 2010 and 2050 in North America (-28 million), Europe (-24 million), Latin America and the Caribbean (-9.5 million), sub-Saharan Africa (-3 million), and Asia-Pacific (2.4 million).[14]

Only in recent decades have surveys begun to measure changes in religious identity among individuals.[14] Religious switching is a sensitive topic in India,[443][6] and carries social and legal repercussions including the death penalty for apostasy in Muslim-majority countries.[6] In China it is difficult to project rates at which Christianity, Islam and Buddhism are gaining converts, nor what are the retention rates among converts.[6]

Religious conversions are projected to have a "modest impact on changes in the Christian population" worldwide between 2010 and 2050.[444] The scenario is missing reliable data of the religious switching in China; because China does not ask about religion in its national statistics.[445][446] According to the same study media reports and expert assessments suggest that conversions to Christianity is rising and growing rapidly in China, also the study cited that "extremely rapid growth of Christianity in China could maintain or, conceivably, even increase Christianity’s current numerical advantage as the world’s largest religion, and it could significantly accelerate the projected decline by 2050 in the share of the global population that is religiously unaffiliated". This scenario was based on sensitivity tests.[78] According to the Pew Research Center, if China is included on data or scenario it may positively affect on the future growth of Christians,[78] and may negatively affect the growth of the Religiously Unaffiliated.[78] On the other hand, according to study by "The Oxford Handbook of Religious Conversion", which published by the professor of Christian mission Charles E. Farhadian,[447] and the professor of psychology Lewis Ray Rambo,[448] between 1990 and 2000, approximately 1.9 million people converted to Christianity from another religion, with Christianity ranking first in net gains through religious conversion.[449]

Notes

- 6 million of those converts came from Indonesia however the report also includes the descendants of those who converted in Indonesia as well.

- the survey was based on 50,000 respondents with 90% of those surveyed living in Iran. The survey was conducted in June 2020 for 15 days from June 17th to July 1st in 2020 and reflects the views of the educated people of Iran over the age of 19 (equivalent to 85% of Adults in Iran) and can be generalized to apply to this entire demographic. It has a 95% confidence level and a 5% margin of error.[200][201]

- Atheism and agnosticism are not typically considered religions, but data about the prevalence of irreligion is useful to scholars of religious demography.

References