Guarani language

Guaraní (/ˌɡwɑːrəˈniː, ˈɡwɑːrəni/)[3] specifically the primary variety known as Paraguayan Guarani (avañeʼẽ [ʔaʋ̃ãɲẽˈʔẽ] "the people's language"), is a South American language that belongs to the Tupi–Guarani family[4] of the Tupian languages. It is one of the official languages of Paraguay (along with Spanish), where it is spoken by the majority of the population, and where half of the rural population is monolingual.[5][6] It is spoken by communities in neighboring countries, including parts of northeastern Argentina, southeastern Bolivia and southwestern Brazil, and is a second official language of the Argentine province of Corrientes since 2004;[7][8] it is also an official language of Mercosur.[9]

| Guaraní | |

|---|---|

| Paraguayan Guarani | |

| avañeʼẽ | |

| Pronunciation | [ʔãʋ̃ãɲẽˈʔẽ] |

| Native to | Paraguay, Bolivia, Argentina, Brazil |

| Ethnicity | Guarani |

Native speakers | (4.85 million cited 1995)[1] |

| Dialects |

|

| Guarani alphabet (Latin script) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by | Academia de la Lengua Guaraní (Avañeʼẽ Rerekuapavẽ) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | gn |

| ISO 639-3 | gug |

| Glottolog | para1311 |

| Linguasphere | 88-AAI-f |

Guarani-speaking world | |

Guaraní is one of the most widely spoken American languages and remains commonly used among the Paraguayan people and neighboring communities. This is unique among American languages; language shift towards European colonial languages (in this case, the other official language of Spanish) has otherwise been a nearly universal phenomenon in the Western Hemisphere, but Paraguayans have maintained their traditional language while also adopting Spanish.

Jesuit priest Antonio Ruiz de Montoya, who in 1639 published the first written grammar of Guarani in a book called Tesoro de la lengua guaraní (Treasure of the Guarani Language / The Guarani Language Thesaurus), described it as a language "so copious and elegant that it can compete with the most famous [of languages]".

The name "Guarani" is generally used for the official language of Paraguay. However, this is part of a dialect chain, most of whose components are also often called Guarani.

History

The persistence of Guarani is, contrary to popular belief, not exclusively, or even primarily, due to the influence of the Jesuits in Paraguay. While Guaraní was the only language spoken in the expansive missionary territories, Paraguayan Guaraní has its roots outside of the Jesuit Reductions.

Modern scholarship has shown that Guarani was always the primary language of colonial Paraguay, both inside and outside the reductions. Following the expulsion of the Jesuits in the 18th century, the residents of the reductions gradually migrated north and west towards Asunción, a demographic shift that brought about a decidedly one-sided shift away from the Jesuit dialect that the missionaries had curated in the southern and eastern territories of the colony.[10][11]

By and large, the Guaraní of the Jesuits shied away from direct phonological loans from Spanish. Instead, the missionaries relied on the agglutinative nature of the language to formulate calque terms from native morphemes. This process often led the Jesuits to employ complicated, highly synthetic terms to convey Western concepts.[12] By contrast, the Guarani spoken outside of the missions was characterized by a free, unregulated flow of Hispanicisms; frequently, Spanish words and phrases were simply incorporated into Guarani with minimal phonological adaptation.

A good example of this phenomenon is found in the word "communion". The Jesuits, using their agglutinative strategy, rendered this word "Tupârahava", a calque based on the word "Tupâ", meaning God.[13] In modern Paraguayan Guaraní, the same word is rendered "komuño".[14]

Following the out-migration from the reductions, these two distinct dialects of Guarani came into extensive contact for the first time. The vast majority of speakers abandoned the less-colloquial, highly regulated Jesuit variant in favor of the variety that evolved from actual language usage by speakers in Paraguay.[15] This contemporary form of spoken Guaraní is known as Jopará, meaning "mixture" in Guarani.

Political status

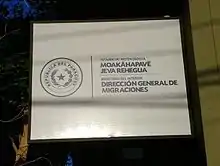

While widely spoken, Paraguayan Guaraní has been repressed by Paraguayan governments throughout most of its history since independence. It was prohibited in state schools for over a hundred years. Nevertheless, populists often used pride in the language to excite nationalistic fervor and promote a narrative of social unity. During the autocratic regime of Alfredo Stroessner, the Colorado Party used the language to appeal to common Paraguayans, although Stroessner himself never gave an address in Guaraní.[16] Upon the advent of Paraguayan democracy in 1992, Guarani was established in the new constitution as a co-equal language along with Spanish.[17] Jopará, the mixture of Spanish and Guaraní, is spoken by an estimated 90% of the population of Paraguay. Code-switching between the two languages takes place on a spectrum where more Spanish is used for official and business-related matters, whereas more Guarani is used in art and in everyday life.[18]

Guarani is also an official language of Bolivia and of Corrientes Province in Argentina.

Writing system

Guarani became a written language relatively recently. Its modern alphabet is basically a subset of the Latin script (with "J", "K" and "Y" but not "W"), complemented with two diacritics and six digraphs. Its orthography is largely phonemic, with letter values mostly similar to those of Spanish. The tilde is used with many letters that are considered part of the alphabet. In the case of Ñ/ñ, it differentiates the palatal nasal from the alveolar nasal (as in Spanish), whereas it marks stressed nasalisation when used over a vowel (as in Portuguese): ã, ẽ, ĩ, õ, ũ, ỹ. (Nasal vowels have been written with several other diacritics: ä, ā, â, ã.) The tilde also marks nasality in the case of G̃/g̃, used to represent the nasalized velar approximant by combining the velar approximant "G" with the nasalising tilde. The letter G̃/g̃, which is unique to this language, was introduced into the orthography relatively recently during the mid-20th century and there is disagreement over its use. It is not a precomposed character in Unicode, which can cause typographic inconveniences – such as needing to press "delete" twice – or imperfect rendering when using computers and fonts that do not properly support the complex layout feature of glyph composition.

Only stressed nasal vowels are written as nasal. If an oral vowel is stressed, and it is not the final syllable, it is marked with an acute accent: á, é, í, ó, ú, ý. That is, stress falls on the vowel marked as nasalized, if any, else on the accent-marked syllable, and if neither appears, then on the final syllable.

For blind people there is also a Guarani Braille.

Phonology

Guarani syllables consist of a consonant plus a vowel or a vowel alone; syllables ending in a consonant or two or more consonants together do not occur. This is represented as (C)V(V).

- Vowels: /a/, /e/, /i/, /o/, /u/ correspond more or less to the Spanish and IPA equivalents, although sometimes the allophones [ɛ], [ɔ] are used more frequently; the grapheme ⟨y⟩ represents the vowel /ɨ/ (as in Polish).

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | /i/, /ĩ/ | /ɨ/, /ɨ̃/ | /u/, /ũ/ |

| Mid | /e/, /ẽ/ | /o/, /õ/ | |

| Open | /a/, /ã/ |

In the below table, the IPA value is shown. The orthography is shown in angle brackets below, if different.

| — | Labial | Alveolar | Alveolo-palatal | Velar | Lab. velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop | Voiceless | p | t | k | kʷ ⟨ku⟩ |

ʔ ⟨'⟩ | |

| Voiced | ᵐb~m ⟨mb~m⟩ |

ⁿd~n ⟨nd~n⟩ |

ᵈj~ɲ ⟨j~ñ⟩ |

ᵑɡ~ŋ ⟨ng⟩ |

ᵑɡʷ~ŋʷ ⟨ngu⟩ |

||

| Fricative | s | ɕ ⟨ch⟩ |

x ~ h ⟨h⟩ | ||||

| Approximant | ʋ ⟨v⟩ |

ɰ ~ ɰ̃ ⟨g⟩ ~ ⟨g̃⟩ |

w ~ w̃ ⟨gu⟩ ~ ⟨g̃u⟩ |

||||

| Flap | ɾ ⟨r⟩ |

||||||

The voiced consonants have oral allophones (left) before oral vowels, and nasal allophones (right) before nasal vowels. The oral allophones of the voiced stops are prenasalized.

There is also a sequence /ⁿt/ (written ⟨nt⟩). A trill /r/ (written ⟨rr⟩), and the consonants /l/, /f/, and /j/ (written ⟨ll⟩) are not native to Guarani, but come from Spanish.

Oral [ᵈj] is often pronounced [dʒ], [ɟ], [ʒ], [j], depending on the dialect, but the nasal allophone is always [ɲ].

The dorsal fricative is in free variation between [x] and [h].

⟨g⟩, ⟨gu⟩ are approximants, not fricatives, but are sometimes transcribed [ɣ], [ɣʷ], as is conventional for Spanish. ⟨gu⟩ is also transcribed [ɰʷ], which is essentially identical to [w].

All syllables are open, viz. CV or V, ending in a vowel.

Glottal stop

The glottal stop, called 'puso' in Guarani, is only written between vowels, but occurs phonetically before vowel-initial words. Because of this, Ayala (2000:19) shows that some words have several glottal stops near each other, which consequently undergo a number of different dissimilation techniques. For example, "I drink water" ʼaʼuʼy is pronounced hauʼy. This suggests that irregularity in verb forms derives from regular sound change processes in the history of Guarani. There also seems to be some degree of variation between how much the glottal stop is dropped (for example aruʼuka > aruuka > aruka for "I bring"). It is possible that word-internal glottal stops may have been retained from fossilized compounds where the second component was a vowel-initial (and therefore glottal stop–initial) root.[20]:19

Nasal harmony

Guarani displays an unusual degree of nasal harmony. A nasal syllable consists of a nasal vowel, and if the consonant is voiced, it takes its nasal allophone. If a stressed syllable is nasal, the nasality spreads in both directions until it bumps up against a stressed syllable that is oral. This includes affixes, postpositions, and compounding. Voiceless consonants do not have nasal allophones, but they do not interrupt the spread of nasality.

For example,

- /ⁿdo+ɾoi+ⁿduˈpã+i/ → [nõɾ̃õĩnũˈpãĩ]

- /ro+ᵐbo+poˈrã/ → [ɾ̃õmõpõˈɾ̃ã]

However, a second stressed syllable, with an oral vowel, will not become nasalized:

- /iᵈjaˈkãɾaˈku/ → [ʔĩɲãˈkãɾ̃ãˈku]

- /aˈkãɾaˈwe/ → [ʔãˈkãɾ̃ãˈwe][21]

That is, for a word with a single stressed vowel, all voiced segments will be either oral or nasal, while voiceless consonants are unaffected, as in oral /ᵐbotɨ/ vs nasal /mõtɨ̃/.

Grammar

Guaraní is a highly agglutinative language, often classified as polysynthetic. It is a fluid-S type active language, and it has been classified as a 6th class language in Milewski's typology. It uses subject–verb–object word order usually, but object–verb when the subject is not specified.[22]

The language lacks gender and has no definite article, but due to influence from Spanish, la is used as a definite article for singular reference, and lo for plural reference. These are not found in Classical Guarani (Guaraniete).

Nouns

Guarani exhibits nominal tense: past, expressed with -kue, and future, expressed with -rã. For example, tetã ruvichakue translates to "ex-president" while tetã ruvicharã translates to "president-elect." The past morpheme -kue is often translated as "ex-", "former", "abandoned", "what was once", or "one-time". These morphemes can even be combined to express the idea of something that was going to be but didn't end up happening. So for example, paʼirãgue is "a person who studied to be a priest but didn't actually finish", or rather, "the ex-future priest". Note that some nouns use -re instead of -kue and others use -guã instead of -rã.[23]

Pronouns

Guarani distinguishes between inclusive and exclusive pronouns of the first person plural.

| first | second | third | |

|---|---|---|---|

| singular | che | nde | haʼe |

| plural | ñande (inclusive), ore (exclusive) |

peẽ | haʼekuéra/ hikuái (*) |

- Hikuái is a Post-verbal pronoun (oHecha hikuái – they see )

Reflexive pronoun: je: ahecha ("I look"), ajehecha ("I look at myself")

Conjugation

Guarani stems can be divided into a number of conjugation classes, which are called areal (with the subclass aireal) and chendal. The names for these classes stem from the names of the prefixes for 1st and 2nd person singular.

The areal conjugation is used to convey that the participant is actively involved, whereas the chendal conjugation is used to convey that the participant is the undergoer. Note that intransitive verbs can take either conjugation, transitive verbs normally take areal, but can take chendal for habitual readings. Nouns can also be conjugated, but only as chendal. This conveys a predicative possessive reading.[24]

Furthermore, the conjugations vary slightly according to the stem being oral or nasal.

| person | areal | aireal | chendal |

|---|---|---|---|

| walk | use | be big | |

| 1s | a-guata | ai-puru | che-tuicha |

| 2s | re-guata | rei-puru | nde-tuicha |

| 3s | o-guata | oi-puru | i-tuicha |

| 1pi | ja-guata | jai-puru | ñande-tuicha |

| 1px | ro-guata | roi-puru | ore-tuicha |

| 2p | pe-guata | pei-puru | pende-tuicha |

| 3p | o-guata | oi-puru | i-tuicha |

Verb root ñeʼẽ ("speak"); nasal verb.

| Singular | Plural | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person | Prefix | Person | Prefix | ||

| 1 che 'I' |

a- | a-ñeʼẽ | 1 ñande (incl.) 'we all' 1 ore (excl.) 'we (just us)' | ña-

ro- |

ña-ñeʼẽ

ro-ñeʼẽ |

| 2 nde 'You' | re- | re-ñeʼẽ | 2 peẽ 'You all' | pe- | pe-ñeʼẽ |

| 3 haʼe 'S/he' | o- | o-ñeʼẽ | 3 haʼekuéra 'They' | o- | o-ñeʼẽ |

Negation

Negation is indicated by a circumfix n(d)(V)-...-(r)i in Guarani. The preverbal portion of the circumfix is nd- for oral bases and n- for nasal bases. For 2nd person singular, an epenthetic e is inserted before the base, for 1st person plural inclusive, an epenthetic a is inserted.

The postverbal portion is -ri for bases ending in -i, and -i for all others. However, in spoken Guarani, the "-ri" portion of the circumfix is frequently omitted for bases ending in "-i".

| Oral verb

japo (do, make) |

Nasal verb

kororõ (roar, snore) |

With ending in "i"

jupi (go up, rise) |

|---|---|---|

| nd-ajapó-i | n-akororõ-i | nd-ajupí-ri |

| nde-rejapó-i | ne-rekororõ-i | nde-rejupí-ri |

| nd-ojapó-i | n-okororõ-i | nd-ojupí-ri |

| nda-jajapó-i | na-ñakororõ-i | nda-jajupí-ri |

| nd-orojapó-i | n-orokororõ-i | nd-orojupí-ri |

| nda-pejapó-i | na-pekororõ-i | nda-pejupí-ri |

| nd-ojapó-i | n-okororõ-i | nd-ojupí-ri |

The negation can be used in all tenses, but for future or irrealis reference, the normal tense marking is replaced by moʼã, resulting in n(d)(V)-base-moʼã-i as in Ndajapomoʼãi, "I won't do it".

There are also other negatives, such as: ani, ỹhỹ, nahániri, naumbre, naʼanga.

Tense and aspect morphemes

- -ramo: marks extreme proximity of the action, often translating to "just barely": Oguahẽramo, "He just barely arrived".[25]:198

- -kuri: marks proximity of the action. Haʼukuri, "I just ate" (ha'u irregular first person singular form of u, "to eat"). It can also be used after a pronoun, ha che kuri, che poʼa, "and about what happened to me, I was lucky".

- -vaʼekue: indicates a fact that occurred long ago and asserts that it's really truth. Okañyvaʼekue, "he/she went missing a long time ago".

- -raʼe: tells that the speaker was doubtful before but he's sure at the moment he speaks. Nde rejoguaraʼe peteĩ taʼangambyry pyahu, "so then you bought a new television after all".

- -rakaʼe: expresses the uncertainty of a perfect-aspect fact. Peẽ peikorakaʼe Asunción-pe, "I think you lived in Asunción for a while". Nevertheless, nowadays this morpheme has lost some of its meaning, having a correspondence with raʼe and vaʼekue.

The verb form without suffixes at all is a present somewhat aorist: Upe ára resẽ reho mombyry, "that day you got out and you went far".

- -ta: is a future of immediate happening, it's also used as authoritarian imperative. Oujeýta ag̃aite, "he/she'll come back soon".

- -ma: has the meaning of "already". Ajapóma, "I already did it".

These two suffixes can be added together: ahátama, "I'm already going".

- -vaʼerã: indicates something not imminent or something that must be done for social or moral reasons, in this case corresponding to the German modal verb sollen. Péa ojejapovaʼerã, "that must be done".

- -ne: indicates something that probably will happen or something the speaker imagines that is happening. It correlates in a certain way with the subjunctive of Spanish. Mitãnguéra ág̃a og̃uahéne hógape, "the children are probably coming home now".

- -hína, ína after nasal words: continual action at the moment of speaking, present and pluperfect continuous or emphatic. Rojatapyhína, "we're making fire"; che haʼehína, "it's ME!".

- -vo: it has a subtle difference with hína in which vo indicates not necessarily what's being done at the moment of speaking. ambaʼapóvo, "I'm working (not necessarily now)".

- -pota: indicates proximity immediately before the start of the process. Ajukapota, "I'm near the point at which I will start to kill" or "I'm just about to kill". (A particular sandhi rule is applied here: if the verbs ends in "po", the suffix changes to mbota; ajapombota, "I'll do it right now").

- -pa: indicates emphatically that a process has all finished. Amboparapa pe ogyke, "I painted the wall completely".

This suffix can be joined with ma, making up páma: ñande jaikuaapáma nde remimoʼã, "now we came to know all your thought".

- -mi: customary action in the past: Oumi, "He used to come a lot".

These are unstressed suffixes: ta, ma, ne, vo, "mi"; so the stress goes upon the last syllable of the verb or the last stressed syllable.

Other verbal morphemes

- -se: desiderative suffix: "(Che) añemoaranduse", "I want to study".[26]

- te-: desiderative prefix: Ahasa, "I pass", Tahasa, "I would like to pass." Note that te- is the underlying form. It is similar to the negative in that it has the same vowel alternations and deletions, depending on the person marker on the verb.[25]:108

Determiners

| Guarani | English | Spanish |

|---|---|---|

| 1 – Demonstratives: | ||

| (a) With near objects and entities (you see it) | ||

| ko | this | este, esta |

| pe | that | ese, esa |

| amo | that/yonder | aquel, aquella |

| peteĩ-teĩ (+/- va) | each | cada uno |

| koʼã, ã, áã | these | estos, estas |

| umi | those | esos, esas, aquellos, aquellas |

| (b) Indefinite, with far objects and entities (you do not see it -remembering demonstratives ): | ||

| ku | that (singular) | aquel, aquella |

| akói | those (plural) | aquellos, as |

| (c) Other usual demonstratives determiners: | ||

| opa | all | todo, toda, todos, todas (with all entities) |

| mayma | all | todos, todas (with people) |

| mbovy- | some, a few, determinate | unos, unas |

| heta | a lot of, very much | muchos, muchas |

| ambue (+/- kuéra) | other | otros, otras |

| ambue | another | otro, otra |

| ambueve: | The other | el otro, la otra |

| ambueve | other, another | otro, otros, (enfático) – |

| oimeraẽ | either | cualquiera |

| mokoĩve | both | ambos, ambas |

| ni peteĩ (+/- ve) | neither | ni el uno ni el otro |

Spanish loans in Guarani

The close and prolonged contact Spanish and Guarani have experienced has resulted in many Guarani words of Spanish origin. Many of these loans were for things or concepts unknown to the New World prior to Spanish colonization. Examples are seen below:[27]

| Semantic category | Spanish | Guarani | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| animals | vaca | vaka | cow |

| caballo | kavaju | horse | |

| cabra | kavara | goat | |

| religion | cruz | kurusu | cross |

| Jesucristo | Hesukrísto | Jesus Christ | |

| Pablo | Pavlo | Paul (saint) | |

| place names | Australia | Autaralia | Australia |

| Islandia | Iylanda | Iceland | |

| Portugal | Poytuga | Portugal | |

| foods | queso | kesu | cheese |

| azúcar | asuka | sugar | |

| morcilla | mbusia | blood sausage | |

| herbs/spices | canela | kanéla | cinnamon |

| cilantro | kuratũ | cilantro | |

| anís | ani | anise |

Guarani loans in English

English has adopted a small number of words from Guarani (or perhaps the related Tupi) via Portuguese, mostly the names of animals. "Jaguar" comes from jaguarete and "piranha" comes from pira aña (evil fish). Other words are: "agouti" from akuti, "tapir" from tapira, "açaí" from ĩwasaʼi ("[fruit that] cries or expels water"), and "warrah" from aguará meaning "fox". Ipecacuanha (the name of a medicinal drug) comes from a homonymous Tupi-Guaraní name that can be rendered as ipe-kaa-guene, meaning a creeping plant that makes one vomit.[28]

The name of Paraguay is itself a Guarani word, as is the name of Uruguay. However, the exact meaning of either placename is up to varied interpretations. (See: List of country-name etymologies.)

"Cougar" is borrowed from the archaic Portuguese çuçuarana; the term was either originally derived from the Tupi language susuaʼrana, meaning "similar to deer (in hair color)" or from the Guaraní language term guaçu ara while puma comes from the Peruvian Quechua language.

Sample text

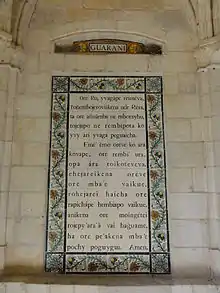

Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Guarani:

Mayma yvypóra ou ko yvy ári iñapytyʼyre ha eteĩcha tekoruvicharenda ha akatúape jeguerekópe; ha ikatu rupi oikuaa añetéva ha añeteʼyva, iporãva ha ivaíva, tekotevẽ pehenguéicha oiko oñondivekuéra.[29]

(All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.)

Literature

The New Testament was translated from Greek into Guaraní by Dr John William Lindsay (1875-1946), who was a Scottish medical missionary based in Belén, Paraguay. The New Testament was printed by the British and Foreign Bible Society in 1913. It is believed to be the first New Testament translated into any South American indigenous language.

A more modern translation of the whole Bible into Guarani is known as Ñandejara Ñeʼẽ.[30]

In 2019, Jehovah's Witnesses released the New World Translation of the Holy Scriptures in Guarani,[31][32] both printed and online editions.

Recently a series of novels in Guarani have been published:

- Kalaito Pombero (Tadeo Zarratea, 1981)

- Poreʼỹ rape (Hugo Centurión, 2016)

- Tatukua (Arnaldo Casco Villalba, 2017)

Institutions

- Ateneo de Lengua y Cultura Guaraní

- Yvy Marãeʼỹ Foundation

See also

Sources

- Guaraní at Ethnologue (19th ed., 2016)

- Guaraní is stablished as «idioma oficial alternativo» ("co-official language") of Corrientes

- Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- Britton, A. Scott (2004). Guaraní-English/English-Guaraní Concise Dictionary. New York: Hippocrene Books.

- Mortimer, K 2006 "Guaraní Académico or Jopará? Educator Perspectives and Ideological Debate in Paraguayan Bilingual Education" Working Papers in Educational Linguistics 21/2: 45-71, 2006

- Romero, Simon (12 March 2012). "In Paraguay, Indigenous Language With Unique Staying Power". The New York Times.

- "Ley Provincial Nº 5.598, que establece el guaraní como "idioma oficial alternativo" de Corrientes>>" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-29. Retrieved 2008-05-22.

- Website of Indigenous Peoples' Affairs which contains this information Archived 2005-10-27 at the Wayback Machine (in Spanish)

- Incorporación del Guaraní como Idioma del Mercosur Archived 2013-12-25 at the Wayback Machine MERCOSUR official page (in Spanish)

- Wilde, Guillermo (2001). "Los guaraníes después de la expulsión de los jesuitas: dinámicas políticas y transacciones simbólicas". Revista Complutense de Historia de América (in Spanish). 27: 69–106.

- Telesca, Ignacio (2009). Tras los expulsos: cambios demográficos y territoriales en el paraguay después de la expulsión de los jesuitas. Asunción: Universidad Católica "Nuestra Señora De La Asunción".

- Harald Thun (2008). Geschichte Und Aktualität Der Deutschsprachigen Guaraní-Philologie: Akten Der Guarani-Tagung in Kiel Und Berlin.

- Restivo, Paulo (1724). Vocabulario de la lengua guaraní (in Spanish). Madrid.

- Guarania, Félix (2008). Ñande Ayvu Tenonde Porãngue'i: Nuevo diccionario guaraní́-castellano, castellano-guaraní́: Avañe'ẽ-karaiñe'ẽ, Karaiñe'ẽ-avañe'ẽ. Asuncion: Servilibro.

- Melia, Bartomeu (2003). La lengua guaraní́ en el Paraguay colonial (in Spanish). Asunción: CEPAG.

- Nickson, Robert Andrew (2009). "Governance and the Revitalization of the Guaraní Language in Paraguay". Latin American Research Review. 44 (3): 3–26. doi:10.1353/lar.0.0115. JSTOR 40783668. S2CID 144250960.

- Romero, Simon (2012-03-12). "An Indigenous Language With Unique Staying Power". New York Times. Retrieved 2019-02-01.

- Page, Nathan (1999-09-06). "Guaraní: The Language and People". Brigham Young University Department of Linguistics. Retrieved 2019-02-01.

- Michael, Lev, Tammy Stark, Emily Clem, and Will Chang (compilers). 2015. Phonological inventory of Paraguayan Guarani. In South American Phonological Inventory Database v1.1.4. Survey of California and Other Indian Languages Digital Resource. Berkeley: University of California.

- Ayala, Valentín (2000). Gramática Guaraní. Asunción: Centro Editorial Paraguayo S.R.L.

- Walker (2000) Nasalization, neutral segments, and opacity effects, p. 210

- Tonhauser, Judith; Colijn, Erika (2010). "Word Order in Paraguayan Guarani". International Journal of American Linguistics. 76 (2): 255–288. doi:10.1086/652267. S2CID 73554080.

- Guasch, P. Antonio (1956). El Idioma Guarnai: Gramática e Antología de Prosa y Verso. Asuncion: Casa América. p. 53.

- Caralho, Jao de(1993) Peixes de Ámérica do Sul, Universidade de Rio de Janeiro

- Graham, Charles R. (1969). Guarani Intermediate Course. Provo: Brigham Young University.

- Blair, Robert; et al. (1968). Guarani Basic Course: Book 1. p. 50.

- Pinta, J. (2013). "Lexical strata in loanword phonology: Spanish loans in Guarani". Master's thesis, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. (See also Lexical stratum.)

- Oxford English Dictionary, "Ipecacuanha".

- "Guarani language, alphabet and pronunciation". Omniglot.com. Retrieved 2013-08-26.

- "Guarani Bible officially included in the Vatican" (in Spanish). Última Hora. 2012-10-23.

- "Jehovahʼs Witnesses Release New World Translation in Guarani". Jw.org. August 20, 2019.

- "¿Orekópa umi testígo de Jehová ibíblia tee?". Jw.org.

External links

| Guarani edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

- Guarani Portal from the University of Mainz:

- www.guaranirenda.com – Website about the Guarani language

- Guarani and the Importance of Maintaining Indigenous Culture Through Language

- Lenguas de Bolivia (online edition)

- Romero, Simon (12 March 2012). "MEMO FROM PARAGUAY; An Indigenous Language With Unique Staying Power". The New York Times. p. 6.

- Duolingo course in Guarani

Resources

- Guarani Swadesh vocabulary list (from Wiktionary)

- Guarani–English Dictionary: from *Webster's Online Dictionary – The Rosetta Edition

- www.guarani.de – Online dictionary in Spanish, German and Guarani

- Guarani Possessive Constructions: – by Maura Velázquez

- Stative Verbs and Possessions in Guarani: – University of Cologne (pdf missing)

- Frases celebres del Latin traducidas al guarani (in Spanish)

- Spanish – Estructura Basica del Guarani and others

- Etymological and Ethnographic Dictionary for Bolivian Guarani

- Guaraní (Intercontinental Dictionary Series)