History of genetics

The history of genetics dates from the classical era with contributions by Pythagoras, Hippocrates, Aristotle, Epicurus, and others. Modern genetics began with the work of the Augustinian friar Gregor Johann Mendel. His work on pea plants, published in 1866, established the theory of Mendelian inheritance.

| Part of a series on |

| Genetics |

|---|

|

| Key components |

| History and topics |

| Research |

|

| Personalized medicine |

| Personalized medicine |

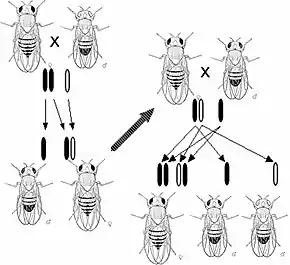

The year 1900 marked the "rediscovery of Mendel" by Hugo de Vries, Carl Correns and Erich von Tschermak, and by 1915 the basic principles of Mendelian genetics had been studied in a wide variety of organisms — most notably the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. Led by Thomas Hunt Morgan and his fellow "drosophilists", geneticists developed the Mendelian model, which was widely accepted by 1925. Alongside experimental work, mathematicians developed the statistical framework of population genetics, bringing genetic explanations into the study of evolution.

With the basic patterns of genetic inheritance established, many biologists turned to investigations of the physical nature of the gene. In the 1940s and early 1950s, experiments pointed to DNA as the portion of chromosomes (and perhaps other nucleoproteins) that held genes. A focus on new model organisms such as viruses and bacteria, along with the discovery of the double helical structure of DNA in 1953, marked the transition to the era of molecular genetics.

In the following years, chemists developed techniques for sequencing both nucleic acids and proteins, while many others worked out the relationship between these two forms of biological molecules and discovered the genetic code. The regulation of gene expression became a central issue in the 1960s; by the 1970s gene expression could be controlled and manipulated through genetic engineering. In the last decades of the 20th century, many biologists focused on large-scale genetics projects, such as sequencing entire genomes.

Pre-Mendelian ideas on heredity

Ancient theories

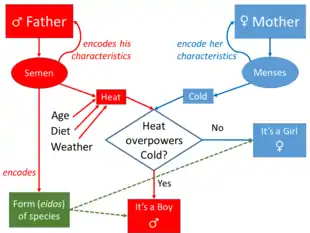

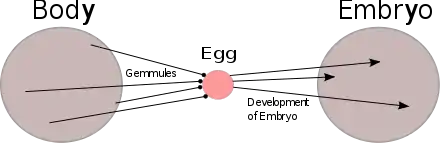

The most influential early theories of heredity were that of Hippocrates and Aristotle. Hippocrates' theory (possibly based on the teachings of Anaxagoras) was similar to Darwin's later ideas on pangenesis, involving heredity material that collects from throughout the body. Aristotle suggested instead that the (nonphysical) form-giving principle of an organism was transmitted through semen (which he considered to be a purified form of blood) and the mother's menstrual blood, which interacted in the womb to direct an organism's early development.[1] For both Hippocrates and Aristotle—and nearly all Western scholars through to the late 19th century—the inheritance of acquired characters was a supposedly well-established fact that any adequate theory of heredity had to explain. At the same time, individual species were taken to have a fixed essence; such inherited changes were merely superficial.[2] The Athenian philosopher Epicurus observed families and proposed the contribution of both males and females of hereditary characters ("sperm atoms"), noticed dominant and recessive types of inheritance and described segregation and independent assortment of "sperm atoms".[3]

In the Charaka Samhita of 300CE, ancient Indian medical writers saw the characteristics of the child as determined by four factors: 1) those from the mother's reproductive material, (2) those from the father's sperm, (3) those from the diet of the pregnant mother and (4) those accompanying the soul which enters into the fetus. Each of these four factors had four parts creating sixteen factors of which the karma of the parents and the soul determined which attributes predominated and thereby gave the child its characteristics.[4]

In the 9th century CE, the Afro-Arab writer Al-Jahiz considered the effects of the environment on the likelihood of an animal to survive.[5] In 1000 CE, the Arab physician, Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi (known as Albucasis in the West) was the first physician to describe clearly the hereditary nature of haemophilia in his Al-Tasrif.[6] In 1140 CE, Judah HaLevi described dominant and recessive genetic traits in The Kuzari.[7]

Preformation theory

The preformation theory is a developmental biological theory, which was represented in antiquity by the Greek philosopher Anaxagoras. It reappeared in modern times in the 17th century and then prevailed until the 19th century. Another common term at that time was the theory of evolution, although "evolution" (in the sense of development as a pure growth process) had a completely different meaning than today. The preformists assumed that the entire organism was preformed in the sperm (animalkulism) or in the egg (ovism or ovulism) and only had to unfold and grow. This was contrasted by the theory of epigenesis, according to which the structures and organs of an organism only develop in the course of individual development (Ontogeny). Epigenesis had been the dominant opinion since antiquity and into the 17th century, but was then replaced by preformist ideas. Since the 19th century epigenesis was again able to establish itself as a view valid to this day.[8][9]

Plant systematics and hybridization

In the 18th century, with increased knowledge of plant and animal diversity and the accompanying increased focus on taxonomy, new ideas about heredity began to appear. Linnaeus and others (among them Joseph Gottlieb Kölreuter, Carl Friedrich von Gärtner, and Charles Naudin) conducted extensive experiments with hybridisation, especially hybrids between species. Species hybridizers described a wide variety of inheritance phenomena, include hybrid sterility and the high variability of back-crosses.[10]

Plant breeders were also developing an array of stable varieties in many important plant species. In the early 19th century, Augustin Sageret established the concept of dominance, recognizing that when some plant varieties are crossed, certain characteristics (present in one parent) usually appear in the offspring; he also found that some ancestral characteristics found in neither parent may appear in offspring. However, plant breeders made little attempt to establish a theoretical foundation for their work or to share their knowledge with current work of physiology,[11] although Gartons Agricultural Plant Breeders in England explained their system.[12]

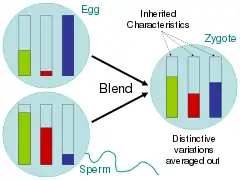

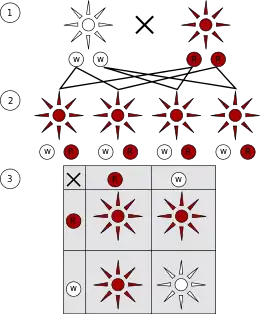

Mendel

Between 1856 and 1865, Gregor Mendel conducted breeding experiments using the pea plant Pisum sativum and traced the inheritance patterns of certain traits. Through these experiments, Mendel saw that the genotypes and phenotypes of the progeny were predictable and that some traits were dominant over others.[13] These patterns of Mendelian inheritance demonstrated the usefulness of applying statistics to inheritance. They also contradicted 19th-century theories of blending inheritance, showing, rather, that genes remain discrete through multiple generations of hybridization.[14]

From his statistical analysis, Mendel defined a concept that he described as a character (which in his mind holds also for "determinant of that character"). In only one sentence of his historical paper, he used the term "factors" to designate the "material creating" the character: " So far as experience goes, we find it in every case confirmed that constant progeny can only be formed when the egg cells and the fertilizing pollen are off like the character so that both are provided with the material for creating quite similar individuals, as is the case with the normal fertilization of pure species. We must, therefore, regard it as certain that exactly similar factors must be at work also in the production of the constant forms in the hybrid plants."(Mendel, 1866).

Mendel's work was published in 1866 as "Versuche über Pflanzen-Hybriden" (Experiments on Plant Hybridization) in the Verhandlungen des Naturforschenden Vereins zu Brünn (Proceedings of the Natural History Society of Brünn), following two lectures he gave on the work in early 1865.[15]

Post-Mendel, pre-rediscovery

Pangenesis

Mendel's work was published in a relatively obscure scientific journal, and it was not given any attention in the scientific community. Instead, discussions about modes of heredity were galvanized by Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection, in which mechanisms of non-Lamarckian heredity seemed to be required. Darwin's own theory of heredity, pangenesis, did not meet with any large degree of acceptance.[16][17] A more mathematical version of pangenesis, one which dropped much of Darwin's Lamarckian holdovers, was developed as the "biometrical" school of heredity by Darwin's cousin, Francis Galton.[18]

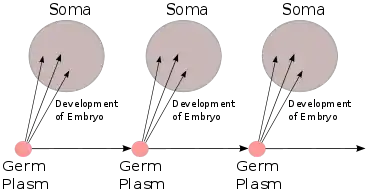

Germ plasm

In 1883 August Weismann conducted experiments involving breeding mice whose tails had been surgically removed. His results — that surgically removing a mouse's tail had no effect on the tail of its offspring — challenged the theories of pangenesis and Lamarckism, which held that changes to an organism during its lifetime could be inherited by its descendants. Weismann proposed the germ plasm theory of inheritance, which held that hereditary information was carried only in sperm and egg cells.[19]

Rediscovery of Mendel

Hugo de Vries wondered what the nature of germ plasm might be, and in particular he wondered whether or not germ plasm was mixed like paint or whether the information was carried in discrete packets that remained unbroken. In the 1890s he was conducting breeding experiments with a variety of plant species and in 1897 he published a paper on his results that stated that each inherited trait was governed by two discrete particles of information, one from each parent, and that these particles were passed along intact to the next generation. In 1900 he was preparing another paper on his further results when he was shown a copy of Mendel's 1866 paper by a friend who thought it might be relevant to de Vries's work. He went ahead and published his 1900 paper without mentioning Mendel's priority. Later that same year another botanist, Carl Correns, who had been conducting hybridization experiments with maize and peas, was searching the literature for related experiments prior to publishing his own results when he came across Mendel's paper, which had results similar to his own. Correns accused de Vries of appropriating terminology from Mendel's paper without crediting him or recognizing his priority. At the same time another botanist, Erich von Tschermak was experimenting with pea breeding and producing results like Mendel's. He too discovered Mendel's paper while searching the literature for relevant work. In a subsequent paper de Vries praised Mendel and acknowledged that he had only extended his earlier work.[19]

Emergence of molecular genetics

After the rediscovery of Mendel's work there was a feud between William Bateson and Pearson over the hereditary mechanism, solved by Ronald Fisher in his work "The Correlation Between Relatives on the Supposition of Mendelian Inheritance".

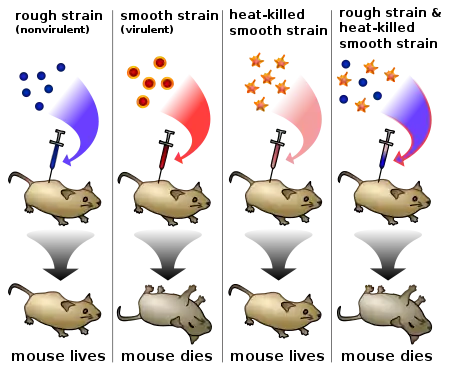

In 1910, Thomas Hunt Morgan showed that genes reside on specific chromosomes. He later showed that genes occupy specific locations on the chromosome. With this knowledge, Alfred Sturtevant, a member of Morgan's famous fly room, using Drosophila melanogaster, provided the first chromosomal map of any biological organism. In 1928, Frederick Griffith showed that genes could be transferred. In what is now known as Griffith's experiment, injections into a mouse of a deadly strain of bacteria that had been heat-killed transferred genetic information to a safe strain of the same bacteria, killing the mouse.

A series of subsequent discoveries led to the realization decades later that the genetic material is made of DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) and not, as was widely believed until then, of proteins. In 1941, George Wells Beadle and Edward Lawrie Tatum showed that mutations in genes caused errors in specific steps of metabolic pathways. This showed that specific genes code for specific proteins, leading to the "one gene, one enzyme" hypothesis.[20] Oswald Avery, Colin Munro MacLeod, and Maclyn McCarty showed in 1944 that DNA holds the gene's information.[21] In 1952, Rosalind Franklin and Raymond Gosling produced a strikingly clear x-ray diffraction pattern indicating a helical form. Using these x-rays and information already known about the chemistry of DNA, James D. Watson and Francis Crick demonstrated the molecular structure of DNA in 1953.[22] Together, these discoveries established the central dogma of molecular biology, which states that proteins are translated from RNA which is transcribed by DNA. This dogma has since been shown to have exceptions, such as reverse transcription in retroviruses.

In 1972, Walter Fiers and his team at the University of Ghent were the first to determine the sequence of a gene: the gene for bacteriophage MS2 coat protein.[23] Richard J. Roberts and Phillip Sharp discovered in 1977 that genes can be split into segments. This led to the idea that one gene can make several proteins. The successful sequencing of many organisms' genomes has complicated the molecular definition of the gene. In particular, genes do not always sit side by side on DNA like discrete beads. Instead, regions of the DNA producing distinct proteins may overlap, so that the idea emerges that "genes are one long continuum".[24][25] It was first hypothesized in 1986 by Walter Gilbert that neither DNA nor protein would be required in such a primitive system as that of a very early stage of the earth if RNA could serve both as a catalyst and as genetic information storage processor.

The modern study of genetics at the level of DNA is known as molecular genetics and the synthesis of molecular genetics with traditional Darwinian evolution is known as the modern evolutionary synthesis.

Early timeline

- 1856–1863: Mendel studied the inheritance of traits between generations based on experiments involving garden pea plants. He deduced that there is a certain tangible essence that is passed on between generations from both parents. Mendel established the basic principles of inheritance, namely, the principles of dominance, independent assortment, and segregation.

- 1866: Austrian Augustinian monk Gregor Mendel's paper, Experiments on Plant Hybridization, published.

- 1869: Friedrich Miescher discovers a weak acid in the nuclei of white blood cells that today we call DNA. In 1871 he isolated cell nuclei, separated the nucleic cells from bandages and then treated them with pepsin (an enzyme which breaks down proteins). From this, he recovered an acidic substance which he called "nuclein".[26]

- 1880–1890: Walther Flemming, Eduard Strasburger, and Edouard Van Beneden elucidate chromosome distribution during cell division.

- 1889: Richard Altmann purified protein free DNA. However, the nucleic acid was not as pure as he had assumed. It was determined later to contain a large amount of protein.

- 1889: Hugo de Vries postulates that "inheritance of specific traits in organisms comes in particles", naming such particles "(pan)genes".[27]

- 1902: Archibald Garrod discovered inborn errors of metabolism. An explanation for epistasis is an important manifestation of Garrod's research, albeit indirectly. When Garrod studied alkaptonuria, a disorder that makes urine quickly turn black due to the presence of gentisate, he noticed that it was prevalent among populations whose parents were closely related.[28][29][30]

- 1903: Walter Sutton and Theodor Boveri independently hypothesizes that chromosomes, which segregate in a Mendelian fashion, are hereditary units;[31] see the chromosome theory. Boveri was studying sea urchins when he found that all the chromosomes in the sea urchins had to be present for proper embryonic development to take place. Sutton's work with grasshoppers showed that chromosomes occur in matched pairs of maternal and paternal chromosomes which separate during meiosis.[32] He concluded that this could be "the physical basis of the Mendelian law of heredity."[33]

- 1905: William Bateson coins the term "genetics" in a letter to Adam Sedgwick[34] and at a meeting in 1906.[35]

- 1908: G.H. Hardy and Wilhelm Weinberg proposed the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium model which describes the frequencies of alleles in the gene pool of a population, which are under certain specific conditions, as constant and at a state of equilibrium from generation to generation unless specific disturbing influences are introduced.

- 1910: Thomas Hunt Morgan shows that genes reside on chromosomes while determining the nature of sex-linked traits by studying Drosophila melanogaster. He determined that the white-eyed mutant was sex-linked based on Mendelian's principles of segregation and independent assortment.[36]

- 1911: Alfred Sturtevant, one of Morgan's collaborators, invented the procedure of linkage mapping which is based on the frequency of crossing-over.[37]

- 1913: Alfred Sturtevant makes the first genetic map,[38] showing that chromosomes contain linearly arranged genes.

- 1918: Ronald Fisher publishes "The Correlation Between Relatives on the Supposition of Mendelian Inheritance" the modern synthesis of genetics and evolutionary biology starts. See population genetics.

- 1920: Lysenkoism Started, during Lysenkoism they stated that the hereditary factor are not only in the nucleus, but also in the cytoplasm, though they called it living protoplasm.[39]

- 1923: Frederick Griffith studied bacterial transformation and observed that DNA carries genes responsible for pathogenicity.[40]

- 1928: Frederick Griffith discovers that hereditary material from dead bacteria can be incorporated into live bacteria.

In Griffith's experiment, mice are injected with dead bacteria of one strain and live bacteria of another, and develop an infection of the dead strain's type.

In Griffith's experiment, mice are injected with dead bacteria of one strain and live bacteria of another, and develop an infection of the dead strain's type. - 1930s–1950s: Joachim Hämmerling conducted experiments with Acetabularia in which he began to distinguish the contributions of the nucleus and the cytoplasm substances (later discovered to be DNA and mRNA, respectively) to cell morphogenesis and development.[41][42]

- 1931: Crossing over is identified as the cause of recombination; the first cytological demonstration of this crossing over was performed by Barbara McClintock and Harriet Creighton.

- 1933: Jean Brachet, while studying virgin sea urchin eggs, suggested that DNA is found in cell nucleus and that RNA is present exclusively in the cytoplasm. At the time, "yeast nucleic acid" (RNA) was thought to occur only in plants, while "thymus nucleic acid" (DNA) only in animals. The latter was thought to be a tetramer, with the function of buffering cellular pH.[43][44]

- 1933: Thomas Morgan received the Nobel prize for linkage mapping. His work elucidated the role played by the chromosome in heredity. Morgan voluntarily shared the prize money with his key collaborators, Calvin Bridges and Alfred Sturtevant.

- 1941: Edward Lawrie Tatum and George Wells Beadle show that genes code for proteins;[45] see the original central dogma of genetics.

- 1943: Luria–Delbrück experiment: this experiment showed that genetic mutations conferring resistance to bacteriophage arise in the absence of selection, rather than being a response to selection.[46]

The DNA era

- 1944: The Avery–MacLeod–McCarty experiment isolates DNA as the genetic material (at that time called transforming principle).[47]

- 1947: Salvador Luria discovers reactivation of irradiated phage,[48] stimulating numerous further studies of DNA repair processes in bacteriophage,[49] and other organisms, including humans.

- 1948: Barbara McClintock discovers transposons in maize.

- 1950: Erwin Chargaff determined the pairing method of nitrogenous bases. Chargaff and his team studied the DNA from multiple organisms and found three things (also known as Chargaff's rules). First, the concentration of the pyrimidines (guanine and adenine) are always found in the same amount as one another. Second, the concentration of purines (cytosine and thymine) are also always the same. Lastly, Chargaff and his team found the proportion of pyrimidines and purines correspond each other.[50][51]

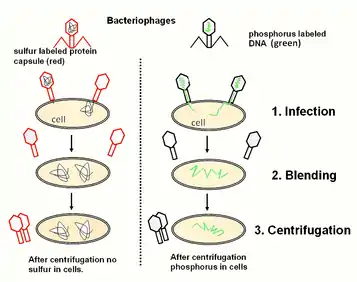

- 1952: The Hershey–Chase experiment proves the genetic information of phages (and, by implication, all other organisms) to be DNA.[52]

- 1952: an X-ray diffraction image of DNA was taken by Raymond Gosling in May 1952, a student supervised by Rosalind Franklin.[53]

- 1953: DNA structure is resolved to be a double helix by James Watson, Francis Crick and Rosalind Franklin[54]

- 1955: Alexander R. Todd determined the chemical makeup of nitrogenous bases. Todd also successfully synthesized adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD). He was awarded the Nobel prize in Chemistry in 1957 for his contributions in the scientific knowledge of nucleotides and nucleotide co-enzymes.[55]

- 1955: Joe Hin Tjio, while working in Albert Levan's lab, determined the number of chromosomes in humans to be of 46. Tjio was attempting to refine an established technique to separate chromosomes onto glass slides by conducting a study of human embryonic lung tissue, when he saw that there were 46 chromosomes rather than 48. This revolutionized the world of cytogenetics.[56]

- 1957: Arthur Kornberg with Severo Ochoa synthesized DNA in a test tube after discovering the means by which DNA is duplicated. DNA polymerase 1 established requirements for in vitro synthesis of DNA. Kornberg and Ochoa were awarded the Nobel Prize in 1959 for this work.[57][58][59]

- 1957/1958: Robert W. Holley, Marshall Nirenberg, Har Gobind Khorana proposed the nucleotide sequence of the tRNA molecule. Francis Crick had proposed the requirement of some kind of adapter molecule and it was soon identified by Holey, Nirenberg and Khorana. These scientists help explain the link between a messenger RNA nucleotide sequence and a polypeptide sequence. In the experiment, they purified tRNAs from yeast cells and were awarded the Nobel prize in 1968.[60]

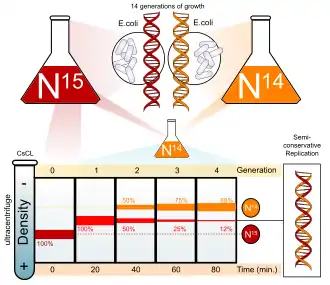

- 1958: The Meselson–Stahl experiment demonstrates that DNA is semiconservatively replicated.[61]

Meselson–Stahl experiment demonstrates DNA is semiconservatively replicated.

Meselson–Stahl experiment demonstrates DNA is semiconservatively replicated. - 1960: Jacob and collaborators discover the operon, a group of genes whose expression is coordinated by an operator.[62][63]

- 1961: Francis Crick and Sydney Brenner discovered frame shift mutations. In the experiment, proflavin-induced mutations of the T4 bacteriophage gene (rIIB) were isolated. Proflavin causes mutations by inserting itself between DNA bases, typically resulting in insertion or deletion of a single base pair. The mutants could not produce functional rIIB protein.[64] These mutations were used to demonstrate that three sequential bases of the rIIB gene's DNA specify each successive amino acid of the encoded protein. Thus the genetic code is a triplet code, where each triplet (called a codon) specifies a particular amino acid.

- 1961: Sydney Brenner, Francois Jacob and Matthew Meselson identified the function of messenger RNA.[65]

- 1964: Howard Temin showed using RNA viruses that the direction of DNA to RNA transcription can be reversed.

- 1964: Lysenkoism ended.

- 1966: Marshall W. Nirenberg, Philip Leder, Har Gobind Khorana cracked the genetic code by using RNA homopolymer and heteropolymer experiments, through which they figured out which triplets of RNA were translated into what amino acids in yeast cells.[66]

- 1969: Molecular hybridization of radioactive DNA to the DNA of cytological preparation by Pardue, M. L. and Gall, J. G.

- 1970: Restriction enzymes were discovered in studies of a bacterium, Haemophilus influenzae, by Hamilton O. Smith and Daniel Nathans, enabling scientists to cut and paste DNA.[67]

- 1972: Stanley Norman Cohen and Herbert Boyer at UCSF and Stanford University constructed Recombinant DNA which can be formed by using restriction Endonuclease to cleave the DNA and DNA ligase to reattach the "sticky ends" into a bacterial plasmid.[68]

The genomics era

- 1972: Walter Fiers and his team were the first to determine the sequence of a gene: the gene for bacteriophage MS2 coat protein.[69]

- 1976: Walter Fiers and his team determine the complete nucleotide-sequence of bacteriophage MS2-RNA.[70]

- 1976: Yeast genes expressed in E. coli for the first time.[71]

- 1977: DNA is sequenced for the first time by Fred Sanger, Walter Gilbert, and Allan Maxam working independently. Sanger's lab sequence the entire genome of bacteriophage Φ-X174.[72][73][74]

- In the late 1970s: nonisotopic methods of nucleic acid labeling were developed. The subsequent improvements in the detection of reporter molecules using immunocytochemistry and immunofluorescence, in conjunction with advances in fluorescence microscopy and image analysis, have made the technique safer, faster and reliable.

- 1980: Paul Berg, Walter Gilbert and Frederick Sanger developed methods of mapping the structure of DNA. In 1972, recombinant DNA molecules were produced in Paul Berg's Stanford University laboratory. Berg was awarded the 1980 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for constructing recombinant DNA molecules that contained phage lambda genes inserted into the small circular DNA mol.[75]

- 1980: Stanley Norman Cohen and Herbert Boyer received first U.S. patent for gene cloning, by proving the successful outcome of cloning a plasmid and expressing a foreign gene in bacteria to produce a "protein foreign to a unicellular organism." These two scientist were able to replicate proteins such as HGH, Erythropoietin and Insulin. The patent earned about $300 million in licensing royalties for Stanford.[76]

- 1982: The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the release of the first genetically engineered human insulin, originally biosynthesized using recombination DNA methods by Genentech in 1978.[77] Once approved, the cloning process lead to mass production of humulin (under license by Eli Lilly & Co.).

- 1983: Kary Banks Mullis invents the polymerase chain reaction enabling the easy amplification of DNA.[78]

- 1983: Barbara McClintock was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for her discovery of mobile genetic elements. McClintock studied transposon-mediated mutation and chromosome breakage in maize and published her first report in 1948 on transposable elements or transposons. She found that transposons were widely observed in corn, although her ideas weren't widely granted attention until the 1960s and 1970s when the same phenomenon was discovered in bacteria and Drosophila melanogaster.[79]

- 1985: Alec Jeffreys announced DNA fingerprinting method. Jeffreys was studying DNA variation and the evolution of gene families in order to understand disease causing genes.[80] In an attempt to develop a process to isolate many mini-satellites at once using chemical probes, Jeffreys took x-ray films of the DNA for examination and noticed that mini-satellite regions differ greatly from one person to another. In a DNA fingerprinting technique, a DNA sample is digested by treatment with specific nucleases or Restriction endonuclease and then the fragments are separated by electrophoresis producing a template distinct to each individual banding pattern of the gel.[81]

Display of VNTR allele lengths on a chromatogram, a technology used in DNA fingerprinting

Display of VNTR allele lengths on a chromatogram, a technology used in DNA fingerprinting - 1986: Jeremy Nathans found genes for color vision and color blindness, working with David Hogness, Douglas Vollrath and Ron Davis as they were studying the complexity of the retina.[82]

- 1987: Yoshizumi Ishino accidentally discovers and describes part of a DNA sequence which later will be called CRISPR.

- 1989: Thomas Cech discovered that RNA can catalyze chemical reactions,[83] making for one of the most important breakthroughs in molecular genetics, because it elucidates the true function of poorly understood segments of DNA.

- 1989: The human gene that encodes the CFTR protein was sequenced by Francis Collins and Lap-Chee Tsui. Defects in this gene cause cystic fibrosis.[84]

- 1992: American and British scientists unveiled a technique for testing embryos in-vitro (Amniocentesis) for genetic abnormalities such as Cystic fibrosis and Hemophilia.

- 1993: Phillip Allen Sharp and Richard Roberts awarded the Nobel Prize for the discovery that genes in DNA are made up of introns and exons. According to their findings, not all the nucleotides on the RNA strand (product of DNA transcription) are used in the translation process. The intervening sequences in the RNA strand are first spliced out so that only the RNA segment left behind after splicing would be translated to polypeptides.[85]

- 1994: The first breast cancer gene is discovered. BRCA I was discovered by researchers at the King laboratory at UC Berkeley in 1990 but was first cloned in 1994. BRCA II, the second key gene in the manifestation of breast cancer was discovered later in 1994 by Professor Michael Stratton and Dr. Richard Wooster.

- 1995: The genome of bacterium Haemophilus influenzae is the first genome of a free living organism to be sequenced.[86]

- 1996: Saccharomyces cerevisiae , a yeast species, is the first eukaryote genome sequence to be released.

- 1996: Alexander Rich discovered the Z-DNA, a type of DNA which is in a transient state, that is in some cases associated with DNA transcription.[87] The Z-DNA form is more likely to occur in regions of DNA rich in cytosine and guanine with high salt concentrations.[88]

- 1997: Dolly the sheep was cloned by Ian Wilmut and colleagues from the Roslin Institute in Scotland.[89]

- 1998: The first genome sequence for a multicellular eukaryote, Caenorhabditis elegans, is released.

- 2000: The full genome sequence of Drosophila melanogaster is completed.

- 2001: First draft sequences of the human genome are released simultaneously by the Human Genome Project and Celera Genomics.

- 2001: Francisco Mojica and Rudd Jansen propose the acronym CRISPR to describe a family of bacterial DNA sequences that can be used to specifically change genes within organisms.

- 2003: Successful completion of Human Genome Project with 99% of the genome sequenced to a 99.99% accuracy.[90]

.jpg.webp) Francis Collins announces the successful completion of the Human Genome Project in 2003

Francis Collins announces the successful completion of the Human Genome Project in 2003 - 2003: Paul Hebert introduces the standardisation of molecular species identification and coins the term 'DNA Barcoding',[91] proposing Cytochrome Oxidase 1 (CO1) as the DNA Barcode for Animals.[92]

- 2004: Merck introduced a vaccine for Human Papillomavirus which promised to protect women against infection with HPV 16 and 18, which inactivates tumor suppressor genes and together cause 70% of cervical cancers.

- 2007: Michael Worobey traced the evolutionary origins of HIV by analyzing its genetic mutations, which revealed that HIV infections had occurred in the United States as early as the 1960s.

- 2007: Timothy Ray Brown becomes the first person cured from HIV/AIDS through a Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

- 2007: The Barcode of Life Data System (BOLD) is set up as an international reference library for molecular species identification (www.barcodinglife.org).[93]

- 2008: Houston-based Introgen developed Advexin (FDA Approval pending), the first gene therapy for cancer and Li-Fraumeni syndrome, utilizing a form of Adenovirus to carry a replacement gene coding for the p53 protein.

- 2009: The Consortium for the Barcode of Life Project (CBoL) Plant Working Group propose rbcL and matK as the duel barcode for land plants.[94]

- 2010: Transcription activator-like effector nucleases (or TALENs) are first used to cut specific sequences of DNA.

- 2011: Fungal Barcoding Consortium propose Internal Transcribed Spacer region (ITS) as the Universal DNA Barcode for Fungi.[95]

- 2012: The flora of Wales is completely barcoded, and reference specimens stored in the BOLD systems database, by the National Botanic Garden of Wales.[96]

- 2016: A genome is sequenced in outer space for the first time, with NASA astronaut Kate Rubins using a MinION device aboard the International Space Station.[97]

See also

References

- Leroi, Armand Marie (2010). Föllinger, S. (ed.). Function and Constraint in Aristotle and Evolutionary Theory. Was ist 'Leben'? Aristoteles' Anschauungen zur Entstehung und Funktionsweise von Leben. Franz Steiner Verlag. pp. 215–221.

- Mayr, The Growth of Biological Thought, pp 635–640

- Yapijakis C. (2017) Ancestral Concepts of Human Genetics and Molecular Medicine in Epicurean Philosophy. In: Petermann H., Harper P., Doetz S. (eds) History of Human Genetics. Springer, Cham

- Bhagwan, Bhagwan; Sharma, R.K. (January 1, 2009). Charaka Samhita. Chowkhamba Sanskrit Series. pp. sharirasthanam II.26–27. ISBN 978-8170800125.

- Zirkle C (1941). "Natural Selection before the "Origin of Species"". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 84 (1): 71–123. JSTOR 984852.

- Cosman, Madeleine Pelner; Jones, Linda Gale (2008). Handbook to life in the medieval world. Infobase Publishing. pp. 528–529. ISBN 978-0-8160-4887-8.

- HaLevi, Judah, translated and annotated by N. Daniel Korobkin. The Kuzari: In Defense of the Despised Faith, p. 38, I:95: "This phenomenon is common in genetics as well—often we find a son who does not resemble his father at all, but closely resembles his grandfather. Undoubtedly, the genetics and resemblance were dormant within the father even though they were not outwardly apparent. Hebrew by Ibn Tibon, p.375: ונראה כזה בענין הטבעי, כי כמה יש מבני האדם שאינו דומה לאב כלל אך הוא דומה לאבי אביו ואין ספק כי הטבע ההוא והדמיון ההוא היה צפון באב ואף על פי שלא נראה להרגשה

- François Jacob: Die Logik des Lebenden. Von der Urzeugung zum genetischen Code. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1972, ISBN 3-10-035601-2

- Ilse Jahn, Rolf Löther, Konrad Senglaub (Editor): Geschichte der Biologie. Theorien, Methoden, Institutionen, Kurzbiographien. 2nd edition. VEB Fischer, Jena 1985

- Mayr, The Growth of Biological Thought, pp 640–649

- Mayr, The Growth of Biological Thought, pp 649–651

- For example, Explanatory Notes, Gartons Seed Catalogue for Spring 1901

- Pierce, Benjamin A. (2020). Genetics A Conceptual Approach (7th ed.). 41 Madison Avenue New York, NY 10010: W.H. Freeman. pp. 49–56. ISBN 978-1-319-29714-5.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Mukherjee, Siddartha (2016) The Gene: An intimate history Chapter 4.

- Alfred, Randy (2010-02-08). "Feb. 8, 1865: Mendel Reads Paper Founding Genetics". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 2019-11-11.

- Darwin, C. R. (1871). Pangenesis. Nature. A Weekly Illustrated Journal of Science 3 (27 April): 502–503.

- Geison, G. L. (1969). "Darwin and heredity: The evolution of his hypothesis of pangenesis". J Hist Med Allied Sci. XXIV (4): 375–411. doi:10.1093/jhmas/XXIV.4.375. PMID 4908353.

- Bulmer, M. G. (2003). Francis Galton: Pioneer of Heredity and Biometry. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 116–118. ISBN 978-0-801-88140-4.

- Mukherjee, Siddartha (2016) The Gene:An intimate history Chapter 5.

- Gerstein MB, Bruce C, Rozowsky JS, Zheng D, Du J, Korbel JO, Emanuelsson O, Zhang ZD, Weissman S, Snyder M (June 2007). "What is a gene, post-ENCODE? History and updated definition". Genome Research. 17 (6): 669–681. doi:10.1101/gr.6339607. PMID 17567988.

- Steinman RM, Moberg CL (February 1994). "A triple tribute to the experiment that transformed biology". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 179 (2): 379–84. doi:10.1084/jem.179.2.379. PMC 2191359. PMID 8294854.

- Pierce, Benjamin A. (2020). Genetics A Conceptual Approach (7th ed.). 41 Madison Avenue New York, NY 10010: W.H. Freeman. pp. 299–300. ISBN 978-1-319-29714-5.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Min Jou W, Haegeman G, Ysebaert M, Fiers W (May 1972). "Nucleotide sequence of the gene coding for the bacteriophage MS2 coat protein". Nature. 237 (5350): 82–8. Bibcode:1972Natur.237...82J. doi:10.1038/237082a0. PMID 4555447. S2CID 4153893.

- Pearson, H. (May 2006). "Genetics: what is a gene?". Nature. 441 (7092): 398–401. Bibcode:2006Natur.441..398P. doi:10.1038/441398a. PMID 16724031. S2CID 4420674.

- Pennisi E (June 2007). "Genomics. DNA study forces rethink of what it means to be a gene". Science. 316 (5831): 1556–1557. doi:10.1126/science.316.5831.1556. PMID 17569836. S2CID 36463252.

- Principles of Genetics / D. Peter Snustad, Michael J. Simmons – 5th Ed. pp.210

- Vries, H. de (1889) Intracellular Pangenesis ("pan-gene" definition on page 7 and 40 of this 1910 translation in English)

- Principles of Biochemistry / Nelson and Cox – 2005. pp.681

- Principles of Genetics / D. Peter Snustad, Michael J. Simmons – 5th Ed. pp. 383–384

- Cell and Molecular Biology, Concepts and experiments / Gerald Karp –5th Ed (2008). pp. 430–431

- Ernest W. Crow & James F. Crow (1 January 2002). "100 years ago: Walter Sutton and the chromosome theory of heredity". Genetics. 160 (1): 1–4. PMC 1461948. PMID 11805039.

- O'Connor, C. & Miko, I. (2008) Developing the chromosome theory. Nature Education

- Sutton, W. S. (1902). "On the morphology of the chromosome group in Brachystola magna" (PDF). Biological Bulletin. 4 (24–3): 39. doi:10.2307/1535510. JSTOR 1535510.

- Online copy of William Bateson's letter to Adam Sedgwick Archived 2007-10-13 at the Wayback Machine

- Bateson, William (1907). "The Progress of Genetic Research". In Wilks, W. (ed.). Report of the Third 1906 International Conference on Genetics: Hybridization (the cross-breeding of genera or species), the cross-breeding of varieties, and general plant breeding. London: Royal Horticultural Society. Although the conference was titled "International Conference on Hybridisation and Plant Breeding", Wilks changed the title for publication as a result of Bateson's speech.

- Principles of Genetics / D. Peter Snustad, Michael J. Simmons – 5th Ed. p.99

- Principles of Genetics / D. Peter Snustad, Michael J. Simmons – 5th Ed. pp.147

- Principles of Genetics / D. Peter Snustad, Michael J. Simmons – 5th Ed. pp.109

- Online summary of "Real Genetic vs. Lysenko Controversy

- Principles of Genetics / D. Peter Snustad, Michael J. Simmons – 5th Ed. pp.190

- Hämmerling, J. (1953). "Nucleo-cytoplasmic Relationships in the Development of Acetabularia". International Review of Cytology Volume 2. International Review of Cytology. 2. pp. 475–498. doi:10.1016/S0074-7696(08)61042-6. ISBN 9780123643025.

- Mandoli, Dina F. (1998). What Ever Happened to Acetabularia? Bringing a Once-Classic Model System into the Age of Molecular Genetics. International Review of Cytology. 182. pp. 1–67. doi:10.1016/S0074-7696(08)62167-1. ISBN 9780123645869.

- Brachet, J. (1933). Recherches sur la synthese de l'acide thymonucleique pendant le developpement de l'oeuf d'Oursin. Archives de Biologie 44* 519–576.

- Burian, R. (1994). Jean Brachet's Cytochemical Embryology: Connections with the Renovation of Biology in France? In: Debru, C., Gayon, J. and Picard, J.-F. (eds.). Les sciences biologiques et médicales en France 1920–1950, vol. 2 of Cahiers pour I'histoire de la recherche. Paris: CNRS Editions, pp. 207–220. link.

- Beadle, GW; Tatum, EL (November 1941). "Genetic Control of Biochemical Reactions in Neurospora". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 27 (11): 499–506. Bibcode:1941PNAS...27..499B. doi:10.1073/pnas.27.11.499. PMC 1078370. PMID 16588492.

- Luria, SE; Delbrück, M (November 1943). "Mutations of Bacteria from Virus Sensitivity to Virus Resistance". Genetics. 28 (6): 491–511. PMC 1209226. PMID 17247100.

- Oswald T. Avery; Colin M. MacLeod & Maclyn McCarty (1944). "Studies on the chemical nature of the substance inducing transformation of pneumococcal types: Induction of transformation by a desoxyribonucleic acid fraction isolated from pneumococcus type III". Journal of Experimental Medicine. 79 (1): 137–58. doi:10.1084/jem.79.2.137. PMC 2135445. PMID 19871359.35th anniversary reprint available

- Luria, SE (1947). "Reactivation of Irradiated Bacteriophage by Transfer of Self-Reproducing Units". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 33 (9): 253–64. Bibcode:1947PNAS...33..253L. doi:10.1073/pnas.33.9.253. PMC 1079044. PMID 16588748.

- Bernstein, C (1981). "Deoxyribonucleic acid repair in bacteriophage". Microbiol. Rev. 45 (1): 72–98. doi:10.1128/MMBR.45.1.72-98.1981. PMC 281499. PMID 6261109.

- Principles of Genetics / D. Peter Snustad, Michael J. Simmons – 5th Ed. pp.217 Table 9.1

- Tamm, C.; Herman, T.; Shapiro, S.; Lipschitz, R.; Chargaff, E. (1953). "Distribution Density of Nucleotides within a Desoxyribonucleic Acid Chain". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 203 (2): 673–688. PMID 13084637.

- Hershey, AD; Chase, M (May 1952). "Independent functions of viral protein and nucleic acid in growth of bacteriophage". J. Gen. Physiol. 36 (1): 39–56. doi:10.1085/jgp.36.1.39. PMC 2147348. PMID 12981234.

- "Due credit". Nature. 496 (7445): 270. 18 April 2013. doi:10.1038/496270a. PMID 23607133.

- Watson JD, Crick FH (Apr 1953). "Molecular structure of nucleic acids; a structure for deoxyribose nucleic acid". Nature. 171 (4356): 737–8. Bibcode:1953Natur.171..737W. doi:10.1038/171737a0. PMID 13054692. S2CID 4253007.

- Todd, AR (1954). "Chemical Structure of the Nucleic Acids". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 40 (8): 748–55. Bibcode:1954PNAS...40..748T. doi:10.1073/pnas.40.8.748. PMC 534157. PMID 16589553.

- Wright, Pearce (11 December 2001). "Joe Hin Tjio The man who cracked the chromosome count". The Guardian.

- Cell and Molecular Biology, Concepts and experiments / Gerald Karp –5th Ed (2008) pp. 548

- Principles of Genetics / D. Peter Snustad, Michael J. Simmons – 5th Ed. (Discovery of DNA polymerase I in E. Coli) pp.255

- https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/2c33/f6d48b74f36a565b93ba759fa23f2dab6ef6.pdf

- Cell and Molecular Biology, Concepts and experiments / Gerald Karp –5th Ed (2008) pp. 467–469

- Meselson, M; Stahl, FW (July 1958). "The replication of DNA in Escherichia coli". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 44 (7): 671–82. Bibcode:1958PNAS...44..671M. doi:10.1073/pnas.44.7.671. PMC 528642. PMID 16590258.

- Jacob, F; Perrin, D; Sánchez, C; Monod, J; Edelstein, S (June 2005). "[The operon: a group of genes with expression coordinated by an operator. C.R.Acad. Sci. Paris 250 (1960) 1727–1729]". Comptes Rendus Biologies. 328 (6): 514–20. doi:10.1016/j.crvi.2005.04.005. PMID 15999435.

- Jacob, F; Perrin, D; Sanchez, C; Monod, J (February 1960). "[Operon: a group of genes with the expression coordinated by an operator]". C. R. Acad. Sci. 250: 1727–9. PMID 14406329.

- Crick, FH; Barnett, L; Brenner, S; Watts-Tobin, RJ (1961). "General nature of the genetic code for proteins". Nature. 192 (4809): 1227–32. Bibcode:1961Natur.192.1227C. doi:10.1038/1921227a0. PMID 13882203. S2CID 4276146.

- "Molecular Station: Structure of protein coding mRNA (2007)". Archived from the original on 2012-04-03. Retrieved 2016-07-11.

- Crick, FH; Barnett, L; Brenner, S; Watts-Tobin, RJ (December 1961). "General nature of the genetic code for proteins". Nature. 192 (4809): 1227–32. Bibcode:1961Natur.192.1227C. doi:10.1038/1921227a0. PMID 13882203. S2CID 4276146.

- Principles of Genetics / D. Peter Snustad, Michael J. Simmons – 5th Ed. (Discovery of DNA polymerase I in E. Coli) pp.420

- Genetics and Genomics Timeline: The discovery of messenger RNA (mRNA) by Sydney Brenner, Francis Crick, Francois Jacob and Jacques Monod

- Min Jou W, Haegeman G, Ysebaert M, Fiers W (May 1972). "Nucleotide sequence of the gene coding for the bacteriophage MS2 coat protein". Nature. 237 (5350): 82–8. Bibcode:1972Natur.237...82J. doi:10.1038/237082a0. PMID 4555447. S2CID 4153893.

- Fiers W, Contreras R, Duerinck F, Haegeman G, Iserentant D, Merregaert J, Min Jou W, Molemans F, et al. (1976). "Complete nucleotide-sequence of bacteriophage MS2-RNA - primary and secondary structure of replicase gene". Nature. 260 (5551): 500–507. Bibcode:1976Natur.260..500F. doi:10.1038/260500a0. PMID 1264203. S2CID 4289674.

- Genetics, "The hisB463 Mutation and Expression of a Eukaryotic Protein in Escherichia coli", Vol. 180, 709–714, October 2008

- Sanger F, Air GM, Barrell BG, Brown NL, Coulson AR, Fiddes CA, Hutchison CA, Slocombe PM, Smith M, et al. (Feb 1977). "Nucleotide sequence of bacteriophage phi X174 DNA". Nature. 265 (5596): 687–95. Bibcode:1977Natur.265..687S. doi:10.1038/265687a0. PMID 870828. S2CID 4206886.

- Sanger, F; Nicklen, S; Coulson, AR (December 1977). "DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 74 (12): 5463–7. Bibcode:1977PNAS...74.5463S. doi:10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. PMC 431765. PMID 271968.

- Principles of Biochemistry / Nelson and Cox – 2005. pp. 296–298

- Cell and Molecular Biology, Concepts and experiments / Gerald Karp –5th Ed (2008). pp. 976–977

- Patents 4 Life: Bertram Rowland 1930–2010. Biotech Patent Pioneer Dies (2010)

- Funding Universe: Genentech, Inc

- Cell and Molecular Biology, Concepts and experiments / Gerald Karp –5th Ed (2008). Pp. 763

- The Significance of Responses of the Genome to Challenge / Barbara McClintock – Science New Series, Vol. 226, No. 4676 (1984), pp. 792–801

- Lemelson MIT Program—Inventor of the week: Alec Jeffreys – DNA FINGERPRINTING (2005)

- Jeffreys, AJ; Wilson, V; Thein, SL (1985). "Individual-specific 'fingerprints' of human DNA". Nature. 316 (6023): 76–79. Bibcode:1985Natur.316...76J. doi:10.1038/316076a0. PMID 2989708. S2CID 4229883.

- Wikidoc: Color Blindness – Inheritance pattern of Color Blindness (2010)

- Cell and Molecular Biology, Concepts and experiments / Gerald Karp –5th Ed (2008) pp. 478

- Kerem B; Rommens JM; Buchanan JA; Markiewicz; Cox; Chakravarti; Buchwald; Tsui (September 1989). "Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: genetic analysis". Science. 245 (4922): 1073–80. Bibcode:1989Sci...245.1073K. doi:10.1126/science.2570460. PMID 2570460.

- A Century of Nobel Prize Recipients / Francis Leroy - 2003. pp 345

- Fleischmann RD; Adams MD; White O; Clayton; Kirkness; Kerlavage; Bult; Tomb; Dougherty; Merrick; McKenney; Sutton; Fitzhugh; Fields; Gocyne; Scott; Shirley; Liu; Glodek; Kelley; Weidman; Phillips; Spriggs; Hedblom; Cotton; Utterback; Hanna; Nguyen; Saudek; et al. (July 1995). "Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd". Science. 269 (5223): 496–512. Bibcode:1995Sci...269..496F. doi:10.1126/science.7542800. PMID 7542800.

- Rich, A; Zhang, S (July 2003). "Timeline: Z-DNA: the long road to biological function" (PDF). Nature Reviews Genetics. 4 (7): 566–572. doi:10.1038/nrg1115. PMID 12838348. S2CID 835548.

- Kresge, N.; Simoni, R. D.; Hill, R. L. (2009). "The Discovery of Z-DNA: the Work of Alexander Rich". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 284 (51): e23–e25. PMC 2791029.

- CNN Interactive: A sheep cloning how-to, more or less(1997) http://www.cnn.com/TECH/9702/24/cloning.explainer/index.html

- National Human Genome Research Institute / The Human Genome Project Completion: FAQs (2010)

- Hebert, Paul D. N.; Cywinska, Alina; Ball, Shelley L.; deWaard, Jeremy R. (2003-02-07). "Biological identifications through DNA barcodes". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 270 (1512): 313–321. doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.2218. ISSN 1471-2954. PMC 1691236. PMID 12614582.

- Hebert, Paul D. N.; Gregory, T. Ryan (2005-10-01). "The Promise of DNA Barcoding for Taxonomy". Systematic Biology. 54 (5): 852–859. doi:10.1080/10635150500354886. ISSN 1076-836X. PMID 16243770.

- RATNASINGHAM, SUJEEVAN; HEBERT, PAUL D. N. (2007-01-24). "BARCODING: bold: The Barcode of Life Data System (http://www.barcodinglife.org)". Molecular Ecology Notes. 7 (3): 355–364. doi:10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.01678.x. ISSN 1471-8278. PMC 1890991. PMID 18784790.

- Hollingsworth, P. M. (2011-11-22). "Refining the DNA barcode for land plants". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (49): 19451–19452. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10819451H. doi:10.1073/pnas.1116812108. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3241790. PMID 22109553.

- Garcia-Hermoso, Dea (2012-09-20). "Faculty of 1000 evaluation for Nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region as a universal DNA barcode marker for Fungi". F1000. doi:10.3410/f.717955047.793460391.

- de Vere, Natasha; Rich, Tim C. G.; Ford, Col R.; Trinder, Sarah A.; Long, Charlotte; Moore, Chris W.; Satterthwaite, Danielle; Davies, Helena; Allainguillaume, Joel (2012-06-06). "DNA Barcoding the Native Flowering Plants and Conifers of Wales". PLOS ONE. 7 (6): e37945. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...737945D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0037945. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3368937. PMID 22701588.

- "DNA sequenced in space for first time". BBC News. 30 August 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

Further reading

- Elof Axel Carlson, Mendel's Legacy: The Origin of Classical Genetics (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 2004.) ISBN 0-87969-675-3

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to History of genetics. |

- Olby's "Mendel, Mendelism, and Genetics," at MendelWeb

- ""Experiments in Plant Hybridization" (1866), by Johann Gregor Mendel," by A. Andrei at the Embryo Project Encyclopedia

- http://www.accessexcellence.org/AE/AEPC/WWC/1994/geneticstln.html

- http://www.sysbioeng.com/index/cta94-11s.jpg

- http://www.esp.org/books/sturt/history/

- http://cogweb.ucla.edu/ep/DNA_history.html

- http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/in_depth/sci_tech/2000/human_genome/749026.stm

- https://web.archive.org/web/20120323085256/http://www.hchs.hunter.cuny.edu/wiki/index.php?title=Modern_Science&printable=yes

- http://jem.rupress.org/content/79/2/137.full.pdf

- http://www.nature.com/physics/looking-back/crick/Crick_Watson.pdf

- Todd, AR (1954). "Chemical Structure of the Nucleic Acids". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 40 (8): 748–55. Bibcode:1954PNAS...40..748T. doi:10.1073/pnas.40.8.748. PMC 534157. PMID 16589553.

- http://www.genomenewsnetwork.org/resources/timeline/1960_mRNA.php

- https://web.archive.org/web/20120403041525/http://www.molecularstation.com/molecular-biology-images/data/503/MRNA-structure.png

- http://www.genomenewsnetwork.org/resources/timeline/1973_Boyer.php

- http://www.genetics.org/cgi/content/full/180/2/709

- Sanger, F; Nicklen, S; Coulson, AR (December 1977). "DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 74 (12): 5463–7. Bibcode:1977PNAS...74.5463S. doi:10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. PMC 431765. PMID 271968.

- Jeffreys, AJ; Wilson, V; Thein, SL (1985). "Individual-specific 'fingerprints' of human DNA". Nature. 316 (6023): 76–79. Bibcode:1985Natur.316...76J. doi:10.1038/316076a0. PMID 2989708. S2CID 4229883.

- Cech, T. R.; Bass, B. L. (1986). "Biological Catalysis by RNA". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 55: 599–629. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.003123. PMID 2427016.

- http://www.cnn.com/TECH/9702/24/cloning.explainer/index.html

- http://www.genome.gov/11006943