Liquorice

Liquorice (British English) or licorice (American English) (/ˈlɪkərɪʃ, -ɪs/ LIK-ər-is(h))[5] is the common name of Glycyrrhiza glabra, a flowering plant of the bean family Fabaceae, from the root of which a sweet, aromatic flavouring can be extracted.

| Liquorice | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | G. glabra |

| Binomial name | |

| Glycyrrhiza glabra | |

| Synonyms[2][3][4] | |

| |

The liquorice plant is a herbaceous perennial legume native to the Western Asia and southern Europe.[1] It is not botanically closely related to anise or fennel, which are sources of similar flavouring compounds. (Another such source, star anise, is even more distant from anise and fennel than liquorice is, despite its similar common name.) Liquorice is used as a flavouring in candies and tobacco, particularly in some European and West Asian countries.

Liquorice extracts have been used in herbalism and traditional medicine.[6] Excessive consumption of liquorice (more than 2 mg/kg per day of pure glycyrrhizinic acid, a liquorice component) may result in adverse effects,[6] such as hypokalemia, increased blood pressure, muscle weakness,[7] and death.[8]

Etymology

The word "liquorice" is derived (via the Old French licoresse) from the Greek γλυκόριζα (glykorrhiza), meaning "sweet root",[9] from γλυκύς (glukus), "sweet"[10] and ρίζα (rhiza), "root",[11][12] the name provided by Dioscorides.[13] It is spelled "liquorice" in most of the Commonwealth, but "licorice" in the United States and sometimes Canada.

Description

Liquorice is a herbaceous perennial, growing to 1 metre (39 in) in height, with pinnate leaves about 7–15 cm (3–6 in) long, with 9–17 leaflets. The flowers are 0.8–1.2 cm (1⁄3–1⁄2 in) long, purple to pale whitish blue, produced in a loose inflorescence. The fruit is an oblong pod, 2–3 cm (3⁄4–1 1⁄8 in) long, containing several seeds.[14] The roots are stoloniferous.[15]

Chemistry

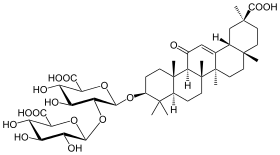

The scent of liquorice root comes from a complex and variable combination of compounds, of which anethole is up to 3% of total volatiles. Much of the sweetness in liquorice comes from glycyrrhizin, which has a sweet taste, 30–50 times the sweetness of sugar. The sweetness is very different from sugar, being less instant, tart, and lasting longer.

The isoflavene glabrene and the isoflavane glabridin, found in the roots of liquorice, are phytoestrogens.[16][17]

Glycyrrhizin is successful in combating SARS CoV and COVID-19.[18][19][20][21]

Cultivation and uses

Liquorice, which grows best in well-drained soils in deep valleys with full sun, is harvested in the autumn two to three years after planting.[14] Countries producing liquorice include India, Iran, Italy, Afghanistan, the People's Republic of China, Pakistan, Iraq, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and Turkey.[22]

The world's leading manufacturer of liquorice products is M&F Worldwide, which manufactures more than 70% of the worldwide liquorice flavours sold to end users.[23]

Tobacco

Liquorice is used as a flavouring agent for tobacco for flavour enhancing and moistening agents in the manufacture of American blend cigarettes, moist snuff, chewing tobacco, and pipe tobacco.[22][24] Liquorice provides tobacco products with a natural sweetness and a distinctive flavour that blends readily with the natural and imitation flavouring components employed in the tobacco industry.[22] As of 2009, the US Food and Drug Administration banned the use of any "characterizing flavors" other than menthol from cigarettes, but not other manufactured tobacco products.[25]

Food and confectionery

Liquorice flavour is found in a wide variety of candies or sweets. In most of these candies, the taste is reinforced by aniseed oil so the actual content of liquorice is very low. Liquorice confections are primarily purchased by consumers in Europe, but are also popular in other countries such as Australia and New Zealand.[22]

In the Netherlands, liquorice confectionery (drop) is one of the most popular forms of sweets. It is sold in many forms. Mixing it with mint, menthol, aniseed, or laurel is quite popular. Mixing it with ammonium chloride (salmiak) is also popular as it is in Finland. A popular example of salmiak liquorice in the Netherlands is known as zoute drop (salty liquorice), but contains very little salt, i.e., sodium chloride.[26] Strong, salty sweets are also popular in Nordic countries where liquorice flavoured alcohols are also popular, particularly in Denmark and Finland.

Dried sticks of the liquorice root are also a traditional confectionery in their own right in the Netherlands as were they once in Britain although their popularity has waned in recent decades. They were sold simply as sticks of zoethout ('sweet wood') to chew on as a candy. Through chewing and suckling, the intensely sweet flavour is released. The sweetness is 30 to 50 times as strong as sucrose, without causing damage to teeth. Since about the 1970s, zoethout has become rarer and been replaced by easier to consume candies (including 'drop').

Pontefract in Yorkshire, England, was the first place where liquorice mixed with sugar began to be used as a sweet in the same way it is today.[27] Pontefract cakes were originally made there.[28] In County Durham, Yorkshire and Lancashire, it is colloquially known as 'Spanish', supposedly because Spanish monks grew liquorice root at Rievaulx Abbey near Thirsk.[29]

In Italy (particularly in the south), Spain and France, liquorice is popular in its natural form. The root of the plant is simply dug up, washed, dried, and chewed as a mouth freshener. Throughout Italy, unsweetened liquorice is consumed in the form of small black pieces made only from 100% pure liquorice extract. In Calabria a popular liqueur is made from pure liquorice extract. Liquorice is used in Syria and Egypt, where it is sold as a drink, in shops as well as street vendors.

Research

Properties of glycyrrhizin are under preliminary research, such as for hepatitis C or topical treatment of psoriasis, but the low quality of studies as of 2017 prevents conclusions about efficacy and safety.[6][30]

Traditional medicine

In traditional Chinese medicine, a related species G. uralensis (often translated as "liquorice") is known as "gancao" (Chinese: 甘草; "sweet grass"), and is believed to "harmonize" the ingredients in a formula.[31] Liquorice has been used in Ayurveda in the belief it may treat various diseases,[32][33][34] although there is no high-quality clinical research to indicate it is safe or effective for any medicinal purpose.

Toxicity

Its major dose-limiting toxicities are corticosteroid in nature, because of the inhibitory effect that its chief active constituents, glycyrrhizin and enoxolone, have on cortisol degradation, and include edema, hypokalaemia, weight gain or loss, and hypertension.[35][36]

The United States Food and Drug Administration believes that foods containing liquorice and its derivatives (including glycyrrhizin) are safe if not consumed excessively. Other jurisdictions have suggested no more than 100 mg to 200 mg of glycyrrhizin per day, the equivalent of about 70 to 150 g (2.5 to 5.3 oz) of liquorice confectionery.[7] Liquorice should not be used during pregnancy.[6]

Liquorice poisoning

Liquorice is an extract from the Glycyrrhiza glabra plant which contains glycyrrhizic acid, or GZA. GZA is made of one molecule of glycyrrhetinic acid and two molecules of glucuronic acid.[37] The extracts from the root of the plant can also be referred to as liquorice, sweet root, and glycyrrhiza extract. G. glabra grows in subtropical climates in Europe and Western Asia. When administered orally, the product of glycyrrhetic acid is found in human urine whereas GZA is not.[37] This shows that glycyrrhetic acid is absorbed and metabolized in the intestines in humans. GZA is hydrolyzed to glycyrrhetic acid in the intestines by bacteria.[38]

For thousands of years G. glabra has been used for medicinal purposes including indigestion and stomach inflammation.[39] Some other medicinal purposes are cough suppression, ulcer treatment, and use as a laxative. Also, salts of GZA can be used in many products as sweeteners and aromatizers. The major use of liquorice goes towards the tobacco industry, at roughly 90% of usage. The rest is split evenly between food and pharmaceutics, at 5% of usage each (Federal Register, 1983). Liquorice extract is often found in sweets and many candies, some drugs, and beverages like root beer. It can also be used in chewing gum, tobacco products like snuff, and toothpaste.

An increase in intake of liquorice can cause many toxic effects. Hyper-mineralocorticosteroid syndrome can occur when the body retains sodium, loses potassium altering biochemical and hormonal activities.[40] Some of these activities include lower aldosterone level, decline of the renin-angiotensin system and increased levels of the atrial natriuretic hormone in order to compensate the variations in homoeostasis.[41]

Some other symptoms of toxicity include electrolyte imbalance, edema, increased blood pressure, weight gain, heart problems, and weakness. Individuals will experience certain symptoms based on the severity of toxicity. Some other complaints include fatigue, shortness of breath, kidney failure, and paralysis.[42][43]References article shows title only without any content to support claim. At least one death has been attributed to excessive licorice consumption.[44]

Many adverse effects of liquorice poisoning can be seen and most are attributed to the mineralocorticoid effects of GZA. Depending on the dose and intake of liquorice, serious problems and even hospitalization can occur. People with previously existing heart or kidney problems may be more susceptible to GZA and liquorice poisoning.[40] It is important to monitor the amount of liquorice consumed in order to prevent toxicity. It is difficult to determine a safe level, due to many varying factors from person to person. In the most sensitive individuals, daily intake of about 100 mg GZA can cause problems.[45] This is equivalent to 50 g liquorice sweets. However, most people can consume up to 400 mg before experiencing symptoms, which would be about 200 g liquorice sweets. A rule of thumb is that a normal healthy person can consume 10 mg GZA a day.[46] In 2020, physicians reported a case of a man who died of cardiac arrest as a result of drastically low potassium levels. He had been eating a bag of black licorice a day for three weeks previously.[8][47]

Gallery

.JPG.webp) Liquorice root with bark

Liquorice root with bark Inflorescence of G. glabra

Inflorescence of G. glabra Various liquorice products

Various liquorice products Different flavoured liquorice sticks

Different flavoured liquorice sticks Foliage

Foliage G. glabra from Koehler's Medicinal-Plants

G. glabra from Koehler's Medicinal-Plants

References

- "Glycyrrhiza glabra". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). Agricultural Research Service (ARS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Retrieved 6 March 2008.

- The Plant List: A Working List of All Plant Species, retrieved 7 March 2017

- The International Plant Names Index, retrieved 7 March 2017

- The International Plant Names Index, retrieved 7 March 2017

- "Liquorice". Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

- "Licorice root". National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, US National Institutes of Health. September 2016. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- Omar, Hesham R; Komarova, Irina; El-Ghonemi, Mohamed; Ahmed, Fathy; Rashad, Rania; Abdelmalak, Hany D; Yerramadha, Muralidhar Reddy; Ali, Yaseen; Camporesi, Enrico M (2012). "How much is too much? in Licorice abuse: time to send a warning message from Therapeutic Advances in Endocrinology and Metabolism". Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 3 (4): 125–38. doi:10.1177/2042018812454322. PMC 3498851. PMID 23185686.

- Edelman, Elazer R.; Butala, Neel M.; Avery, Laura L.; Lundquist, Andrew L.; Dighe, Anand S. (2020-09-24). Cabot, Richard C.; Rosenberg, Eric S.; Pierce, Virginia M.; Dudzinski, David M.; Baggett, Meridale V.; Sgroi, Dennis C.; Shepard, Jo-Anne O.; Tran, Kathy M.; Roberts, Matthew B. (eds.). "Case 30-2020: A 54-Year-Old Man with Sudden Cardiac Arrest". New England Journal of Medicine. 383 (13): 1263–1275. doi:10.1056/NEJMcpc2002420. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 32966726.

- γλυκόριζα, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- γλυκύς, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ῥίζα, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus<

- liquorice, on Oxford Dictionaries

- google books Maud Grieve, Manya Marshall - A modern herbal: the medicinal, culinary, cosmetic and economic properties, cultivation and folk-lore of herbs, grasses, fungi, shrubs, & trees with all their modern scientific uses, Volume 2 Dover Publications, 1982 & Pharmacist's Guide to Medicinal Herbs Arthur M. Presser Smart Publications, 1 April 2001 2012-05-19

- Huxley, A., ed. (1992). New RHS Dictionary of Gardening. ISBN 0-333-47494-5

- Brown, D., ed. (1995). "The RHS encyclopedia of herbs and their uses". ISBN 1-4053-0059-0

- Somjen, D.; Katzburg, S.; Vaya, J.; Kaye, A. M.; Hendel, D.; Posner, G. H.; Tamir, S. (2004). "Estrogenic activity of glabridin and glabrene from licorice roots on human osteoblasts and prepubertal rat skeletal tissues". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 91 (4–5): 241–246. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.04.008. PMID 15336701. S2CID 16238533.

- Tamir, S.; Eizenberg, M.; Somjen, D.; Izrael, S.; Vaya, J. (2001). "Estrogen-like activity of glabrene and other constituents isolated from licorice root". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 78 (3): 291–298. doi:10.1016/S0960-0760(01)00093-0. PMID 11595510. S2CID 40171833.

- Pilcher, HelenR. (2003-06-13). "Liquorice may tackle SARS". Nature: news030609–16. doi:10.1038/news030609-16. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 7095480.

- Cinatl, J.; Morgenstern, B.; Bauer, G.; Chandra, P.; Rabenau, H.; Doerr, H. W. (2003-06-14). "Glycyrrhizin, an active component of liquorice roots, and replication of SARS-associated coronavirus". Lancet. 361 (9374): 2045–2046. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13615-x. ISSN 1474-547X. PMC 7112442. PMID 12814717.

- Bailly, Christian; Vergoten, Gérard (2020-10-01). "Glycyrrhizin: An alternative drug for the treatment of COVID-19 infection and the associated respiratory syndrome?". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 214: 107618. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107618. ISSN 0163-7258. PMC 7311916. PMID 32592716.

- Hoever, Gerold; Baltina, Lidia; Michaelis, Martin; Kondratenko, Rimma; Baltina, Lia; Tolstikov, Genrich A.; Doerr, Hans W.; Cinatl, Jindrich (February 2005). "Antiviral Activity of Glycyrrhizic Acid Derivatives against SARS−Coronavirus". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 48 (4): 1256–1259. doi:10.1021/jm0493008. ISSN 0022-2623. PMID 15715493.

- M & F Worldwide Corp., Annual Report on Form 10-K for the Year Ended December 31, 2010.

- M & F Worldwide Corp., Annual Report on Form 10-K for the Year Ended December 31, 2001.

- Erik Assadourian, Cigarette Production Drops Archived 2011-12-09 at the Wayback Machine, Vital Signs 2005, at 70.

- "Flavored Tobacco". US Food and Drug Administration. 22 September 2009. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- the online Dutch food composition database]

- "Right good food from the Ridings". AboutFood.com. 25 October 2007. Archived from the original on 7 June 2007.

- "The strange story of Britain's oldest sweet". BBC Travel. 2019-07-11.

- "Where Liquorice Roots Go Deep". Northern Echo. Retrieved 9 December 2008.

- Yu, J. J; Zhang, C. S; Coyle, M. E; Du, Y; Zhang, A. L; Guo, X; Xue, C. C; Lu, C (2017). "Compound glycyrrhizin plus conventional therapy for psoriasis vulgaris: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Current Medical Research and Opinion. 33 (2): 279–287. doi:10.1080/03007995.2016.1254605. PMID 27786567. S2CID 4394282.

- Bensky, Dan; et al. (2004). Chinese Herbal Medicine: Materia Medica, Third Edition. Eastland Press. ISBN 978-0-939616-42-8.

- Balakrishna, Acharya (2006). Ayurveda: Its Principles & Philosophies. New Delhi, India: Divya prakashan. p. 206. ISBN 978-8189235567.

- Tewari, D; Mocan, A; Parvanov, E. D; Sah, A. N; Nabavi, S. M; Huminiecki, L; Ma, Z. F; Lee, Y. Y; Horbańczuk, J. O; Atanasov, A. G (2017). "Ethnopharmacological Approaches for Therapy of Jaundice: Part II. Highly Used Plant Species from Acanthaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Asteraceae, Combretaceae, and Fabaceae Families". Frontiers in Pharmacology. 8: 519. doi:10.3389/fphar.2017.00519. PMC 5554347. PMID 28848436.

- Wendy Christensen (2009). Empire of Ancient Egypt. Infobase Publishing. pp. 98–. ISBN 978-1-60413-160-4.

- Olukoga, A; Donaldson, D (June 2000). "Liquorice and its health implications". The Journal of the Royal Society for the Promotion of Health. 120 (2): 83–9. doi:10.1177/146642400012000203. PMID 10944880. S2CID 39005138.

- Armanini, D; Fiore, C; Mattarello, MJ; Bielenberg, J; Palermo, M (September 2002). "History of the endocrine effects of licorice". Experimental and Clinical Endocrinology & Diabetes. 110 (6): 257–61. doi:10.1055/s-2002-34587. PMID 12373628.

- Krähenbühl, Stephan; Hasler, Felix; Krapf, Reto (1994). "Analysis and pharmacokinetics of glycyrrhizic acid and glycyrrhetinic acid in humans and experimental animals". Steroids. 59 (2): 121–126. doi:10.1016/0039-128X(94)90088-4. ISSN 0039-128X. PMID 8191540. S2CID 22198298.

- Akao, Taiko; Akao, Teruaki; Kobashi, Kyoichi (1987). "Glycyrrhizin .BETA.-D-glucuronidase of Eubacterium sp. from human intestinal flora". Chemical and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 35 (2): 705–710. doi:10.1248/cpb.35.705. ISSN 0009-2363. PMID 3594680.

- Gibson, M. R. (1978). "Glycyrrhiza in old and new perspectives". Lloydia. 41 (4): 348–354. PMID 353426.

- Omar, H. R.; Komarova, I.; El-Ghonemi, M.; Fathy, A.; Rashad, R.; Abdelmalak, H. D.; Yerramadha, M. R.; Ali, Y.; Helal, E.; Camporesi, E. M. (2012). "Licorice abuse: time to send a warning message". Therapeutic Advances in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 3 (4): 125–138. doi:10.1177/2042018812454322. ISSN 2042-0188. PMC 3498851. PMID 23185686.

- Mackenzie, Marius A.; Hoefnagels, Willibrord H. L.; Jansen, Renè W. M. M.; Benraad, Theo J.; Kloppenborg, Peter W. C. (1990). "The Influence of Glycyrrhetinic Acid on Plasma Cortisol and Cortisone in Healthy Young Volunteers". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 70 (6): 1637–1643. doi:10.1210/jcem-70-6-1637. ISSN 0021-972X. PMID 2161425.

- Blachley, Jon D.; Knochel, James P. (1980). "Tobacco Chewer's Hypokalemia: Licorice Revisited". New England Journal of Medicine. 302 (14): 784–785. doi:10.1056/NEJM198004033021405. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 6986557.

- Toner, J. M.; Ramsey, L. E. (1985). "Liquorice can damage your health". Practitioner. 229 (1408): 858–860. PMID 4059165.

- "Man dies after eating bag of licorice every day for a few weeks". Associated Press. 24 September 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- Adeneye, Adejuwon Adewale (2014). "Subchronic and Chronic Toxicities of African Medicinal Plants". Toxicological Survey of African Medicinal Plants. pp. 99–133. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-800018-2.00006-6. ISBN 9780128000182. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Størmer, F.C.; Reistad, R.; Alexander, J. (1993). "Glycyrrhizic acid in liquorice—Evaluation of health hazard". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 31 (4): 303–312. doi:10.1016/0278-6915(93)90080-I. ISSN 0278-6915. PMID 8386690.

- Cramer, Maria (2020-09-26). "A Man Died After Eating a Bag of Black Licorice Every Day". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-09-27.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Liquorice. |

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 16 (11th ed.). 1911.

- Glycyrrhiza glabra (licorice), Kew plant profile

- What's That Stuff?: Licorice, Chemical & Engineering News