Glycyrrhizin

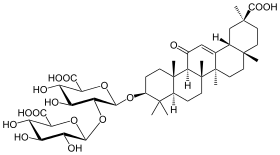

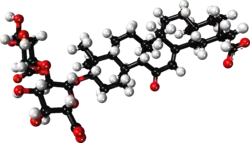

Glycyrrhizin (or glycyrrhizic acid or glycyrrhizinic acid) is the chief sweet-tasting constituent of Glycyrrhiza glabra (liquorice) root. Structurally, it is a saponin used as an emulsifier and gel-forming agent in foodstuffs and cosmetics. Its aglycone is enoxolone.

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Epigen, Glycyron |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Routes of administration | Oral, intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Hepatic and by intestinal bacteria |

| Elimination half-life | 6.2–10.2 hours[1] |

| Excretion | Faeces, urine (0.31–0.67%)[2] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| E number | E958 (glazing agents, ...) |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.014.350 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C42H62O16 |

| Molar mass | 822.942 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Solubility in water | 1–10 mg/mL (20 °C) |

| |

| |

Pharmacokinetics

After oral ingestion, glycyrrhizin is first hydrolysed to 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid (enoxolone) by intestinal bacteria. After complete absorption from the gut, 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid is metabolised to 3β-monoglucuronyl-18β-glycyrrhetinic acid in the liver. This metabolite then circulates in the bloodstream. Consequently, its oral bioavailability is poor. The main part is eliminated by bile and only a minor part (0.31–0.67%) by urine.[3] After oral ingestion of 600 mg of glycyrrhizin the metabolite appeared in urine after 1.5 to 14 hours. Maximal concentrations (0.49 to 2.69 mg/L) were achieved after 1.5 to 39 hours and metabolite can be detected in the urine after 2 to 4 days.[3]

Flavouring properties

Glycyrrhizin is obtained as an extract from licorice root after maceration and boiling in water.[4] Licorice extract (glycyrrhizin) is sold in the United States as a liquid, paste, or spray-dried powder.[4] When in specified amounts, it is approved for use as a flavor and aroma in manufactured foods, beverages, candies, dietary supplements, and seasonings.[4] It is 30 to 50 times as sweet as sucrose (table sugar).[5]

Adverse effects

The most widely reported side effect of glycyrrhizin use via consumption of black licorice is reduction of blood potassium levels, which can affect body fluid balance and function of nerves.[6][7] Chronic consumption of black licorice, even in moderate amounts, is associated with an increase in blood pressure,[7] may cause irregular heart rhythm, and may have adverse interactions with prescription drugs.[6] In extreme cases death can occur as a result of excess consumption.[8][9]

References

- van Rossum TG, Vulto AG, Hop WC, Schalm SW (December 1999). "Pharmacokinetics of intravenous glycyrrhizin after single and multiple doses in patients with chronic hepatitis C infection". Clinical Therapeutics. 21 (12): 2080–90. doi:10.1016/S0149-2918(00)87239-2. hdl:1765/73160. PMID 10645755.

- Ploeger B, Mensinga T, Sips A, Seinen W, Meulenbelt J, DeJongh J (May 2001). "The pharmacokinetics of glycyrrhizic acid evaluated by physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling". Drug Metabolism Reviews. 33 (2): 125–47. doi:10.1081/DMR-100104400. PMID 11495500. S2CID 24778157.

- Kočevar Glavač, Nina; Kreft, Samo (2012). "Excretion profile of glycyrrhizin metabolite in human urine". Food Chemistry. 131: 305–308. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.08.081.

- "Sec. 184.1408 Licorice and licorice derivatives". US Food and Drug Administration, Code of Federal Regulations Title 21, 21CFR184.1408. 1 April 2017. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- "Glycyrrhizic Acid". PubChem. National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- "Black Licorice: Trick or Treat?". US Food and Drug Administration. 30 October 2017. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- Penninkilampi R, Eslick EM, Eslick GD (November 2017). "The association between consistent licorice ingestion, hypertension and hypokalaemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Human Hypertension. 31 (11): 699–707. doi:10.1038/jhh.2017.45. PMID 28660884. S2CID 205168217.

- Marchione, Marilynn. "Too much candy: Man dies from eating bags of black licorice". AP News. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- Edelman, Elazer R.; Butala, Neel M.; Avery, Laura L.; Lundquist, Andrew L.; Dighe, Anand S. (24 September 2020). "Case 30-2020: A 54-Year-Old Man with Sudden Cardiac Arrest". New England Journal of Medicine. 383 (13): 1263–1275. doi:10.1056/NEJMcpc2002420.

External links

![]() Media related to Glycyrrhizin at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Glycyrrhizin at Wikimedia Commons