Sichuan pepper

Sichuan pepper (Chinese: 花椒; pinyin: huājiāo) (also Szechuan pepper, Szechwan pepper, Chinese prickly ash, Chinese pepper, rattan pepper, and mala pepper[1]) is a spice commonly used in the Sichuan cuisine of China's southwestern Sichuan Province. When eaten it produces a tingling, numbing effect due to the presence of hydroxy-alpha sanshool in the peppercorn.[2] It is commonly used in Sichuan dishes such as mapo doufu and Chongqing hot pot, and is often added together with chili peppers to create a flavor known as málà (Chinese: 麻辣; "numb-spiciness").[3]

| Sichuan pepper | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 花椒 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "flower pepper" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 山椒 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Despite its name, Sichuan pepper is not closely related to either black pepper or chili pepper. It belongs to the global genus Zanthoxylum in the family Rutaceae, which includes citrus and rue.[4] Related species are used in the cuisines of several other countries across Asia.

Varieties

China

Sichuan peppers have been used for culinary and medicinal purposes in China for centuries. The two varieties most commonly found in China are Honghuajiao (Chinese: 红花椒), or red Sichuan peppercorns, which are harvested from Z. bungeanum, and Qinghuajiao (Chinese: 青花椒), green Sichuan peppercorns, harvested from Z. armatum. Over the years Chinese farmers have cultivated multiple strains of these two varieties.[6]

Other regions

Z. piperitum is harvested in Japan and Korea to produce sanshō (山椒) or chopi (초피), which has numbing properties similar to those of Chinese Sichuan peppercorns.[7] The Korean sancho (산초, 山椒) refers to a different but related species (Z. schinifolium), which is slightly less bitter than chopi.[8]

In Western India, one variant of Sichuan pepper known as teppal in Konkani or tirphal in Marathi (both words mean "three fruits/pods") is harvested from Z. rhetsa.[9] Another variety, Z. armatum, is found throughout the Himalayas, from Kashmir to Bhutan, as well as in Taiwan, Nepal, China, Philippines, Malaysia, Japan, and Pakistan,[10] and is known by a variety of regional names including timur (टिमुर) in Nepali,[11] yer ma (གཡེར་མ) in Tibetan[12] and thingye in Bhutan.[13]

In Indonesia's North Sumatra province, Z. acanthopodium is harvested and known as andaliman.[14]

Culinary uses

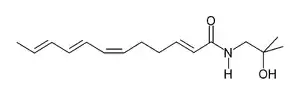

Sichuan pepper has a citrus-like flavor and induces a tingling numbness in the mouth due to the presence of hydroxy-alpha sanshool, which causes a vibration on the lips measured at 50 Hertz.[15] Food historian Harold McGee describes the effect of sanshools thus:

"...they produce a strange, tingling, buzzing, numbing sensation that is something like the effect of carbonated drinks or of a mild electric current (touching the terminals of a nine-volt battery to the tongue). Sanshools appear to act on several different kinds of nerve endings at once, induce sensitivity to touch and cold in nerves that are ordinarily nonsensitive, and so perhaps cause a kind of general neurological confusion."[16]

Chinese cuisine

The peppercorn may be used whole or finely ground, as it is in five-spice powder.[17] Ma la sauce (Chinese: 麻辣; pinyin: málà; literally "numbing and spicy"), common in Sichuan cooking, is a combination of Sichuan pepper and chili pepper, and it is a key ingredient in Chongqing hot pot.[18] Sichuan pepper is also occasionally used in pastries such as Jiāo Yán Bǐng.[19] Beijing microbrewery Great Leap Brewing uses Sichuan peppercorns, offset by honey, as a flavouring adjunct in its Honey Ma Blonde.[20]

Sichuan pepper is also available as an oil (Chinese: 花椒油, marketed as either "Sichuan pepper oil", "Bunge prickly ash oil", or "huajiao oil"). Sichuan pepper infused oil can be used in dressing, dipping sauces, or any dish in which the flavor of the peppercorn is desired without the texture of the peppercorns themselves.[21]

Hua jiao yan (simplified Chinese: 花椒盐; traditional Chinese: 花椒鹽; pinyin: huājiāoyán) is a mixture of salt and Sichuan pepper, toasted and browned in a wok, and served as a condiment to accompany chicken, duck, and pork dishes.[22]

Other regions

Sichuan pepper is an important spice in Nepali, Northeast Indian, Tibetan, and Bhutanese cookery of the Himalayas. One Himalayan specialty is the momo, a dumpling stuffed with vegetables, cottage cheese, or minced yak or beef, and flavored with Sichuan pepper, garlic, ginger, and onion.[23]

In Korean cuisine, sancho is often used to accompany fish soups such as chueo-tang.[24]

In Konkani cuisine, especially among Goud Saraswat Brahmins (GSB), Teppal or Sichuan Pepper is a delicious addition to fish as well as vegetable dishes (Koddel, Gashi, Ambat of different gourds, pulses and other vegetables).

In Indonesian Batak cuisine, andaliman is ground and mixed with chilies and seasonings into a green sambal or chili paste.[25] Arsik is a typical Indonesian dish containing andaliman.[26]

Medicinal uses

In China, Zanthoxylum bungeanum has traditionally been used as an herbal remedy, listed in the Pharmacopoeia of the People's Republic of China and prescribed for ailments as various as abdominal pain, toothache, and eczema. Research has revealed that Z. bungeanum can have analgesic, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and antioxidant effects.[27] Pharmacological basis has also been found for the medicinal use of Z. armatum to treat gastrointestinal, respiratory and cardiovascular disorders.[28]

Phytochemistry

Important aromatic compounds of various Zanthoxylum species include:

- Zanthoxylum fagara (Central & Southern Africa, South America) — alkaloids, coumarins (Phytochemistry, 27, 3933, 1988)

- Zanthoxylum simulans (Taiwan) — Mostly beta-myrcene, limonene, 1,8-cineole, Z-beta-ocimene (J. Agri. & Food Chem., 44, 1096, 1996)

- Zanthoxylum armatum (Nepal) — linalool (50%), limonene, methyl cinnamate, cineole

- Zanthoxylum rhetsa (India) — Sabinene, limonene, pinenes, para-cymene, terpinenes, 4-terpineol, alpha-terpineol. (Zeitschrift f. Lebensmitteluntersuchung und -forschung A, 206, 228, 1998)

- Zanthoxylum piperitum (Japan [leaves]) — citronellal, citronellol, Z-3-hexenal (Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry, 61, 491, 1997)

- Zanthoxylum acanthopodium (Indonesia) — citronellal, limonene[29]

US import ban

From 1968 to 2005,[30] the United States Food and Drug Administration banned the importation of Sichuan peppercorns because they were found to be capable of carrying citrus canker (as the tree is in the same family, Rutaceae, as the genus Citrus). This bacterial disease, which is very difficult to control, could potentially harm the foliage and fruit of citrus crops in the U.S. It was never an issue of harm in human consumption. The import ban was only loosely enforced until 2002.[31] In 2005, the USDA and FDA lifted the ban,[32] provided the peppercorns are heated for ten minutes to around 140 °F (60 °C) to kill any canker bacteria before import.[33]

As of 2007, the USDA no longer requires dried fruit to be subjected to heat treatment in order to be allowed to enter the US. Taking into account that the peppercorn is normally shipped and used dried, this change effectively means that there is no longer an active import ban on the peppercorns.[34]

See also

References

- Wei (15 December 2019). "Sichuan Pepper: Your Questions Answered". redhousespice.com. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- Holliday, Taylor (23 October 2017). "Where the Peppers Grow". Slate.com. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- Gritzer, Daniel; Dunlop, Fuchsia (13 January 2020). "Get to Know Málà, Sichuan Food's Most Famous Flavor". seriouseats.com. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- Zhang, Mengmeng; Wang, Jiaolong (October 2017). "Zanthoxylum bungeanum Maxim. (Rutaceae): A Systematic Review of Its Traditional Uses, Botany, Phytochemistry, Pharmacology, Pharmacokinetics, and Toxicology". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 18 (10): 2172. doi:10.3390/ijms18102172. PMC 5666853. PMID 29057808. S2CID 1057880. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- 临夏县概况 (Linxia County overview)

- Xiang, Li; Liu, Yue (April 2016). "The Chemical and Genetic Characteristics of Szechuan Pepper (Zanthoxylum bungeanum and Z. armatum) Cultivars and Their Suitable Habitat". Frontiers in Plant Science. 7: 467. doi:10.3389/fpls.2016.00467. PMC 4835500. PMID 27148298. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- Ravindran, P. N. (2017). "100 Japanese Pepper Zanthoxylum piperitum". The Encyclopedia of Herbs and Spices. CAB International. pp. 473–476. ISBN 978-1-780-64315-1.

- "Szechuan Peppercorns)". CooksInfo.com. 17 June 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "Tirphal/ Teppal Pepper". foodsofnations.com. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- Kanwal, Rabia; Arshad, Muhammed (22 February 2015). "Evaluation of Ethnopharmacological and Antioxidant Potential of Zanthoxylum armatum DC". Journal of Chemistry. 2015: 1–8. doi:10.1155/2015/925654. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- Kala, Chandra Prakash; Farooquee, Nehal A; Dhar, Uppeandra (2005). "Traditional Uses and Conservation of Timur (Zanthoxylum armatum DC.) through Social Institutions in Uttaranchal Himalaya, India". Conservation and Society. 3 (1): 224–230. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "Some Spices and Ingredients". simplytibetan.com. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- Tshering Dema. "Kingdom Essences: An Essential Oil Brand Which Harnesses Natural Ingredients From Rural Bhutan". DailyBhutan.com. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "Andaliman – A Family of Sichuan Pepper". IndonesiaEats.com. 3 November 2006. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- Holliday, Taylor (23 October 2017). "Where the Peppers Grow". Slate.com/. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- McGee, Harold (2007). On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen. New York: Scribner. p. 429. ISBN 978-1-4165-5637-4.

- "How to Make Five-Spice Powder". thewoksoflife.com. 3 February 2020. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- Holliday, Taylor (7 February 2020). "Sichuan Mala Hot Pot, From Scratch (Mala Huo Guo with Tallow Broth)". themalamarket.com. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "Sichuan Pepper: Your Questions Answered". redhousespice.com. 15 December 2019. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- Levine, Jonathan (20 June 2013). "Beijing's microbrewery boom". CNN. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- "Sichuan Peppercorn Oil". thewoksoflife.com. 3 April 2020. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- "Fragrant crispy duck with Sichuan pepper salt (香酥鸭)". soyricefire.com. 18 November 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- Nguyen, Andrea (19 November 2009). "Recipe: Tibetan Beef and Sichuan Peppercorn Dumplings ('Sha Momo')". NPR. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- Gowman, Philip (5 December 2016). "In praise of Sancho and Flat Three". londonkoreanlinks.net. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- Leifsson, Lanny (8 November 2011). "Sambal Andaliman Recipe (Andaliman Pepper Sambal)". indonesiaeats.com. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "Arsik Recipe (Spiced Carp with Torch Ginger and Andaliman – Mandailing Style)". indonesiaeats.com. 12 July 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- Zhang, Mengmeng; Wang, Jiaolong (October 2017). "Zanthoxylum bungeanum Maxim. (Rutaceae): A Systematic Review of Its Traditional Uses, Botany, Phytochemistry, Pharmacology, Pharmacokinetics, and Toxicology". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 18 (10): 2172. doi:10.3390/ijms18102172. PMC 5666853. PMID 29057808.

- Khan, Arif; Gilani, Anwar-ul Hassan (January 2009). "Pharmacological Basis for the Medicinal Use of Zanthoxylum armatum in Gut, Airways and Cardiovascular Disorders". Phytotherapy Research. 24 (4): 553–8. doi:10.1002/ptr.2979. PMID 20041426. S2CID 22485048. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- Wijaya, CH; Triyanti, I; Apriyantono, A (2002). "Identification of Volatile Compounds and Key Aroma Compounds of Andaliman Fruit (Zanthoxylum acanthopodium DC)". Food Science and Biotechnology. 11 (6): 680–683.

- "eCFR — Code of Federal Regulations". www.ecfr.gov. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- Landis, Denise (4 February 2004). "Sichuan's Signature Fire Is Going Out. Or Is It?". The New York Times. p. F1.

- Amster-Burton, Matthew (17 May 2017). "Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About Sichuan Peppercorns". Village Voice. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- Holliday, Taylor (23 October 2017). "Where the Peppers Grow". Slate. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- "China's Sichuan Peppercorns -- Banned From the US No More - USDA". www.usda.gov.

Sources

- Hu, Shiu-ying (2005). Food plants of China (preview). 1. Chinese University Press. ISBN 9789629962296.

- Zhou, Jiaju; Xie, Guirong; Yan, Xinjian (2011). Encyclopedia of Traditional Chinese Medicines - Molecular Structures (preview). 1. Springer. ISBN 9783642167355.

- Zhang, Dianxiang; Hartley, Thomas G. (2008). "1. Zanthoxylum Linnaeus, Sp. Pl. 1: 270. 1753". Flora of China. 11: 53–66. PDF

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sichuan pepper. |