Living with the enemy in the German-occupied Channel Islands

The German occupation of the Channel Islands lasted from 30 June 1940 to 9 May 1945. During that time, the Channel Islanders had to live under and obey the laws of Nazi Germany and work with their occupiers in order to survive and reduce the impact of occupation. Given no guidance on how to behave by the British government, there were individuals who got close to the enemy and a few who undertook resistance activities. Most had no choice but to accept the changes and depredations to their lives and hope that external forces would someday remove the forces of occupation. It was almost five years before the islanders experienced UK rule again.

Background

The Bailiwick of Jersey comprises the island of Jersey and many islets. The Bailiwick of Guernsey comprises the islands of Guernsey, Alderney, Sark, and a few small unoccupied islands and islets.

Over 25,000 people had been evacuated to Britain including most children, but 41,101 remained on Jersey, 24,429 on Guernsey, and 470 on Sark. Alderney had just 18.[1]:10 The governments in Jersey and in Guernsey were operational, though the emergency services were understaffed due to the evacuation to the UK.

The British Government had decided on 15 June to demilitarise the islands, so all military personnel, weapons, and equipment had been taken to England.[2]:50 They did not tell the Germans, and on 28 June German bombers appeared in the skies and bombed and strafed various places on both islands, including the harbours of Saint Peter Port and Saint Helier,[3]:36 killing 44 and wounding over 70 civilians. A ship in Guernsey harbour returned ineffective fire.[4]:40–44

While the German commanders were finalising their plans for Operation Grünpfeil (Green Arrows) to invade the islands with assault troops, a German Dornier Do 17 pilot decided to land on 30 June at Guernsey airport and have a look around. He returned to France and notified his superiors that the island appeared to be undefended. More aircraft were sent over. A Junkers Ju 52 landed, and the Germans were given a note by the head of the police confirming the islands were not defended.[2]:130 The next day, aircraft brought German troops to both islands: the occupation had begun.

Guidance on occupation

While Great Britain had occupied distant overseas territories in the past, there was little to no advice on how citizens were expected to behave under occupation. The British Treason Act 1800, as amended, gave the consequences of treason. The British Treachery Act 1940 was only passed as a law in the UK on 23 May 1940. The only Jersey law on treason dated from 17 June 1495.[5]

The island governments, headed by their bailiffs, Victor Carey in Guernsey and Alexander Coutanche in Jersey, had been ordered by the British Government to remain on their islands to maintain law and order and to do what they could for the civilians.[6]:42 This put them under a duty of care. When the lieutenant governors, who were the king's representatives on each island, departed on 21 June 1940, their powers and duties were vested in the bailiffs, namely to protect the islands and their population, taking on the duties of the lieutenant governors added a further duty of care.[7]:2

Changes to government operation

In Jersey the Defence (Jersey) Regulations had been passed in 1939 in accordance with powers granted under the Emergency Powers (Jersey Defence) Order in Council of 1939 (although it later transpired that the Privy Council revoked that Order in 1941, unknown to the States of Jersey, thereby putting in doubt the legal basis of measures taken in accordance with the law as it was believed to have been).

The traditional consensus-based governments of the bailiwicks were unsuited to swift executive action, and therefore in the face of imminent occupation, smaller instruments of government were adopted.

In Guernsey, the States of Deliberation voted on 21 June 1940 to hand responsibility for running island affairs to a Controlling Committee, under the presidency of HM Attorney General Ambrose Sherwill. Sherwill was selected rather than the bailiff, Sir Victor Carey, as he was a younger and more robust person.[8]:45 The committee was given almost all the executive power of the States, and had a quorum of three persons under the president (who could nominate additional members). Membership of the Controlling Committee was initially eight members.[9] Sherwill was imprisoned by the Germans as a result of his attempts to shelter the British servicemen in the fallout from Operation Ambassador in 1940. He was released but banned from office in January 1941.[9] Jurat John Leale replaced him as president of the Controlling Committee.[10]

The States of Jersey passed the Defence (Transfer of Powers) (Jersey) Regulation 1940 on 27 June 1940 to amalgamate the various executive committees into eight departments each under the presidency of a States member. The presidents along with the Crown Officers made up the Superior Council under the presidency of the bailiff.[9]

Since the legislatures met in public session, the creation of smaller executive bodies that could meet behind closed doors enabled freer discussion of matters such as how far to comply with German orders.[9]

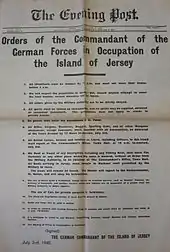

German orders

The German Feldkommandantur 515 (FK515) led by Colonel Rudolf Graf von Schmettow until October 1941, then Colonel Friedrich Knackfuss until February 1944 and finally Major Heider, dealt with civilian matters with the island civil authorities.[11]:16

The military consisted of varying numbers of troops, around 25,000 in October 1944, with an additional 15,000 Organisation Todt (OT) workers once fortification of the islands began in October 1941.[4]:179–180

There was some animosity between the troops in the garrison and FK515 men who were mainly civilians.[12]:48

German soldiers were ordered to be polite to the islanders, and in the beginning, they were. There were no rules against them fraternising so long as they behaved like gentlemen. Soldiers were punished for crimes against civilians.[6]:118 As the war progressed and soldiers were rotated out to other war zones, however, the quality of soldiers decreased, affecting their manners and attitudes. Serious problems started to arise in the last year of occupation when food was in short supply.[7]:26

The local German command seems to have tried to keep the civilian population as happy as possible, letting them govern themselves, paying them for work done and not enacting too many draconian orders sent over from France. Resistance activity by islanders would not be tolerated, however. Punishment of the guilty served as a deterrent to others.

The Germans used propaganda on the islanders. Open air band concerts were promoted, and one of the 1942 deportees, Irishman Denis Cleary, was returned to the island with glowing reports of centrally-heated huts, soldiers carrying the luggage of the internees and abundant food.[13]:44–50

There were no Waffen-SS troops, except in Alderney although some people seeing the few men wearing a black panzer uniform with a deaths head collar badge mistook these tank men for SS.[12]:74

Discipline

German soldiers would without fail obey orders from their superiors.[12]:64 The discipline imposed over the German soldiers was generally very good, although as troops were rotated and poorer quality Ostlegionen soldiers serving in the German army began to arrive, there was a fall. Most men realised that they had a safe and secure billet and would not risk a transfer to the eastern front.[12]:66

Soldiers quickly discovered that the islanders did not consider themselves British but were loyal to the King and Queen, simply looking forward to the day when the Germans would depart.[12]:66 Most soldiers kept their distance from the islanders although some fraternisation took place[12]:147 and a few soldiers returned after the war to marry their sweethearts. Some soldiers were granted leave to return to Germany and visit their families although as the war progressed, the stories they brought back of bombed cities reduced morale.

Off duty the soldiers were entertained in many ways: locally produced newspapers, they could go to the cinema or one of the churches, there was live entertainment and sport was encouraged. Soldatenheime were established, being similar to a British NAAFI or American PX, officers established clubs. Freudenhaus or brothels were established in Guernsey and Jersey, importing women to work in them. Hobbies, including photography,[12]:140–47 and of course there were the beaches.

The islands were promoted as a tourist destination for German soldiers with guide book 'Die Kanalinseln: Jersey - Guernsey - Sark' by Hans Auerbach which was printed in 1942 in Paris.

Working with the Germans

Civil authorities

The island authorities were allowed to continue managing the civilian population, courts and services with limited interference, subject to all new laws requiring German knowledge (and therefore consent) and any German originating laws would require the civil authorities to register them in the same manner as local laws.[14]:55

The civil authorities of each island, represented by the bailiffs, the elected members of the island parliaments, civil servants and emergency services, had of necessity to work in a professional manner with the occupiers for the benefit of the civil population. They had been ordered to do this by the Secretary of State in letters dated 19 June 1940.[15]:82 It did not stop the Germans from using such arrangements for publicity purposes, such as photographing "British" policemen driving cars, opening doors for and saluting German officers.[16]

On 8 August 1940, less than two months into the occupation, Ambrose Sherwill, President of the Controlling Committee of Guernsey, broadcast on German radio that, while the Channel Islanders remained the "intensely loyal subjects" of the British Sovereign, the behaviour of the German soldiers on Guernsey was "exemplary" and he was grateful for their "correct and kindly attitude." He affirmed that the leaders of the Guernsey government were being treated with courtesy by the German military. Life, he said, was going on just as it did before the occupation. Sherwill's objective was to ease the minds of relatives in Britain about the fate of the islanders. German authorities made propaganda usage of his broadcast. The British government was furious, but Sherwill's speech seems to have been greeted with approval by most of the islander population.[17]

Sherwill's broadcast illustrated the difficulty for the islander government and citizens to co-operate—but stop short of collaborating—with their occupiers and to retain as much independence as possible from German rule. The issue of islander collaboration with the Germans remained quiescent for many years, but was ignited in the 1990s with the release of wartime archives and the subsequent publication of a book titled The Model Occupation: The Channel Islands under German Rule, 1940–1945 by Madeleine Bunting. Language such as the title of one chapter, "Resistance? What Resistance?" incited islander ire.[18] The issue of collaboration was further inflamed by the fictional television programme Island at War (2004) which featured a romance between a German soldier and an islander girl and portrayed favourably the German military commander of the occupation.

Bunting's point was that the Channel Islanders "did not fight on the beaches, in the fields or in the streets. They did not commit suicide, and they did not kill any Germans. Instead they settled down, with few overt signs of resistance, to a hard, dull but relatively peaceful five years of occupation, in which more than half the population was working for the Germans."[19]

On occasion, the island authorities did not undertake their work in the best way possible, for instance offering a reward of £25 for the capture of anyone drawing "V" signs, in today's value, £1,000.[20]:32 Not being able to explain what they were doing and why, it would leave some inhabitants believing their governments were collaborating with the enemy rather than trying to protect them.[6]:49

From the start, the islands won the right to keep their civil governments, courts and laws, the only concession being that Germans would have to approve all new laws passed. All German orders affecting the population would have to be registered with the civil authorities, breaches of which would normally be tried in civilian courts rather than German military ones.[6]:54 To lose this right would result in direct German rule, with the SS and Gestapo moving into the islands. The Germans threatened to do this on various occasions. Under this agreement, unacceptable laws created by the Germans, such as rules regarding Jews, were also registered as laws in the islands.[6]:59–60[14]:55–56

Each island could use their committees, a "Controlling Committee" in Guernsey[15]:84 and an "Executive Bodies" in Jersey, and enacted emergency powers to enable the running of the governments. What was achieved, could be described as subtle passive resistance. Co-operation had benefits, such as getting permission to obtain wood for civilian use, keeping rations at a higher level, being allowed to use German shipping to import food and clothing from France. A number of cases of police officers turning blind eyes to activities has been recorded, as well as getting Germans arrested for crimes.[21]

Mistakes were made. On 1 August 1940, a message was recorded by Ambrose Sherwill to the people in the United Kingdom and especially the children of islanders who had evacuated. With all normal communications shut down, he wanted to let these people know that those left behind were not being mistreated and that the Germans were behaving like gentlemen. Accepted as such by most islanders, when broadcast from Germany it was viewed differently in Britain, coming as it did in the midst of the Battle of Britain. The BBC did not repeat the broadcast as requested.[2]:79

Like many occupied countries, the islands were required to pay the costs of the German troops that were stationed there, including wages, rent, food, drinks, transport and the salaries of those they employed.[4]:89 Objections to paying for an excessive number of troops were raised, and some of the sums charged from 1942 onwards were never paid; however, the income tax rose from 10d to 5/- in Guernsey and from 1/6 to 5/- in Jersey. Surtax and purchase taxes was introduced[22]:184 and civil service pay reduced, but even so, the islands ended the war with a debt of £9 million,[7]:108 roughly the total value of every house in the islands.

It was in the interests of both the Germans and the island authorities to clamp down on black market activities. Hoarding food and selling "under the counter" were crimes often linked to thefts and were dealt with by the island police and the military police. Interrogations by the Feldgendarmerie (German Field Police) might involve beatings with "rubber hoses".[23]:222

Money provided by the Germans, who paid for such things as vehicles they requisitioned, was used, with German help, to fund trips to France to buy thousands of tons of essential food and other materials.[24]:126 This continued while shipping was made available, until mid 1944.

Unpalatable laws put forward by the Germans were sometimes openly argued against. Laws regarding registration of, and restrictions applied to, Jews were registered in the islands, which caused controversy after the war. The civil authorities could not win many of these battles.[6]:231 One that Jersey won, was the refusal to allow the "evacuation" to France of patients from their mental health hospital.[11]:261

The civil authorities were often asked to accumulate information, not knowing what it would be used for; in August 1940 a list of aliens showed 407 in Guernsey.[4]:112 In October 1940, they produced a list of all German, Austrian and Italian people.[23]:72 A census was held of all civilians in August 1941. In September 1941, the census was used to make a list of all British-born people. This list identified people for deportation to camps in Germany in 1942 and 1943.[25]:xv

Civilians

Prior to the arrival of the German forces, the largest employer had been the States of Jersey and the States of Guernsey. Under the occupation, everything changed, and working-age people who remained still needed jobs to feed their families and themselves. Unemployment in Jersey at Christmas 1940 was 2,400 men.[2]:95 Many businesses closed or operated on reduced staffing levels, so many jobs vanished. The island governments tried to create suitable relief work. The island authorities introduced pay scales that were lower for single men or men whose wives and children were in England. They also cut the salaries of civil servants in half.[15]:111–12

Civilian buses were suspended in July 1940. The drivers were still employed by the bus company, but were required to transport German soldiers instead.[4]:90 Similar situations existed in hotels taken over by Germans.

The German occupying forces, which had a need for builders, electricians, plumbers, mechanics, cleaning staff, quarry men, secretarial staff, labourers, translators and many other trades and skills, offered twice the normal island pay.[26]:65 All young men in the islands were required to register with the Feldkommandantur so they could be assessed and "recruited" as workers if not employed in useful work elsewhere.[27]:45 By 1943, around 4,000 islanders were directly employed by the Germans.[7]:72 Most of the skilled workers in the German building businesses under the collective Organisation Todt (OT) were volunteers, paid for their work and fed better than the drafted forced labourers from many nations, who were treated like slaves. The Germans would demand labour be provided. One job involving 180 men was to help level the airport, a clear breach of the Geneva Convention. Others, like gathering in the harvest in Alderney, were less objectionable.[7]:73–74

Everyone had to put up with ID cards and a list of rules, such as not singing patriotic songs and cycling on the right, restrictions such as curfews and on fishing,[2]:229 rationing, requisition of houses (2,750 in Guernsey).[4]:273 The Germans requisitioned lorries, cars and bicycles, requiring the island government to pay for them.[22]:167[28]:44 and confiscation of radios and subversive books.[22]:154 Necessary items ran out as the war progressed. German soldiers and OT workers were billeted in 17,000 private houses in 1942.[11]:253 Children had to learn German in school.[24]:155 Infrequent Red Cross messages between February 1941 and June 1944 were the only communication the islanders had with their evacuated children, relatives and friends.[22]:195–99

The position of churches and chapels was not easy and while German ministers held military services in borrowed churches, where a German flag was placed over the altar, civilian services were open to all worshippers and many services took place attended by islanders, Germans and OT workers including Russians, praying, singing and taking communion together.[29]:82–98 Services were sometimes attended by the Feldgendarmerie to ensure sermons complied with the rules.

The deportations of 2190 UK-born men, women, children and babies to Germany, the main group in September 1942, triggered a few suicides in Guernsey, Sark and Jersey, as well as the first public show of patriotism, resulting in arrests and imprisonment.[1]:44–57 Despite this, the treatment by Germans of the "evacuees" was better than those experienced in other European countries, the Germans provided field kitchens to cook food for the evacuees at the Guernsey harbour, they were put onboard clean ships, transporting them in second class train carriages rather than in horse boxes and giving them rations for the journey.

The 100,000 mines were a risk[11]:225 that a few people found were fatal. However, lack of essential medicines, like insulin, caused more deaths amongst civilians.

Survival became increasingly hard with reduced rations and lack of fuel. Death rates rose as the occupation progressed.[7]:116–17 Those with money could supplement their diet with black market produce. Islanders were saved from starvation with the arrival of the SS Vega, bringing Red Cross parcels during the winter of 1944–1945.

During the occupation, no civilian was deported for work in factories in Germany as occurred in most occupied countries. Local people working for the OT were paid and did so voluntarily, they were only employed in the islands. The OT set a pay rate of 60 per cent over normal civilian workers wages for Channel Island workers.[30]:150 German behaviour towards civilians was generally much better than in any other occupied zone.

Commerce

Banks, whose main assets were inaccessible at their headquarters in London, had to freeze the bank accounts of their customers. The island governments had to stand guarantor to the banks to get them to make advances to people.[15]:112

Most businesses continued to operate when possible and stocks lasted. They were not allowed to discriminate between local and German customers. The Germans had a very favourable exchange rate, so while shops had goods, including clothes, boots, cigarettes, tea and coffee, they bought everything up in massive quantities and posted them back to Germany, many for resale at a profit. Shops did not hold stocks back for locals until later in the war.[22]:82 Business hours were reduced, shop workers who had worked nine-hour days, 15 on Saturdays, were reduced to 20 hours a week.[31]:28

A few businesses decided to work for the Germans. The Guernsey firm Timmer Limited, horticultural suppliers, took over increasing quantities of requisitioned land and greenhouses to grow food exclusively for Germans, and were given access to German transport facilities to export food to France.[4]:417

Criminal activity

The German military police, the Feldgendarmerie (Field Police), worked with the civilian police to maintain law and order.[23] The German military court tried all crimes involving Germans and civilian criminal activities involving German interests.

In the autumn of 1940, a 70-year-old Guernsey woman was raped at gunpoint by a German soldier. He was tried by a military court and shot within 10 days.[15]:105 This was one of only two cases of rape in Guernsey during the war and the only German to be shot, but others were imprisoned for injuring civilians.

Antagonising the Germans achieved little, but had consequences. Putting "V" marks on signs and walls had island police rubbing them out before the Feldgendarmerie saw them. The police also found and warned children as young as six against the offence. German reaction was initially mild with warnings, then radios were confiscated from areas where the signs appeared, then men were required to stand guard duty in rotation all night for weeks to avoid a recurrence.[23]:100–105 On 21 February 1945, the Germans in Jersey used tar to daub hundreds of houses with swastikas. Four nights later in St Helier, many red, white and blue Union flags and "V" signs appeared overnight.[11]:26

Civilian crimes against Germans or German property were supposed to be referred to the German police, many instances were overlooked at some risk to the policemen involved. Some police gave out verbal warnings of the dangers of being caught. In 1942, 18 Guernsey police officers were tried before the German military court for stealing or receiving foodstuffs and wood from a German military store.[32]

Thefts of food were high in the list of crimes. Guernsey police recorded the following cases:[33]:62

|

|

|

|

A total of around 4,000 islanders were sentenced for breaking laws during the five-year occupation, just over one per cent of the population per annum.[10] People had to wait to serve prison time due to overcrowding and the fact that many cells were requisitioned for German soldiers, men sentenced to solitary confinement had to share cells.[34] 570 prisoners were sent to continental prisons and camps, of whom at least 31 died.[10]

Black market activity

Hoarding food and goods became an industry as rationing became stricter and shortages grew worse. Farmers would keep back crops and not register animals born. Goods could always be traded. Both hoarding and bartering were illegal. There were 100 prosecutions in Guernsey in 1944, up from 40 in 1942.[7]:67

Black marketeering was large scale and profitable. A French doctor was found with a ton each of potatoes and salted beef, and a Jersey youth had £800 in his bank account when caught, a house could be bought for £250 and he was only 16 years old. Some black marketeers were Germans, including officers, and black market restaurants operated.[7]:67–68 People were caught breaking and entering and stealing goods to sell on the black market. One case in Guernsey of a Frenchman involved 20,000 cigarettes and 40 kg (88 lb) of tobacco.[23]:219 Even civilian prisoners could supplement their worse than normal rations by paying heavily for black market foods to be brought to them.[29]:106 Importing restricted goods from France for the black market was not considered a problem by the civilian police as it supplemented local supplies.

In Alderney, the Lager Sylt commandant, Karl Tietz was brought before a court-martial in April 1943 and sentenced to 18 months penal servitude for the crime of selling on the black market, cigarettes and watches and valuables he had bought from Dutch OT workers.[35]:147

Resistance

Resistance took place in the islands, and if people were caught the penalties were severe, a number of civilians died in prisons. There were few instances of active resistance and immaterial damage was done to the occupying forces.

The most visible sign of passive resistance occurred in Guernsey following the sinking of HMS Charybdis and HMS Limbourne on 23 October 1943, the bodies of 21 Royal Navy and Royal Marines men were washed up in Guernsey. The funeral attracted over 20 per cent of the population, laying 900 wreaths. This was enough of a demonstration against the occupation for subsequent military funerals to be closed to civilians by the German occupiers.[36] The ceremony is commemorated annually.

Apart from islanders serving in the allied armed forces, the islands can claim the most damage done to the Nazi regime was absorbing large quantities of concrete and steel and keeping 30,000 German troops mis-deployed, who could have been used elsewhere to defend the Third Reich.[37]

One of the French artillery pieces brought to the island and installed in Batterie Strassburg at Jerbourg Point in 1942 may have been sabotaged in France, as the breach exploded on the 22 cm gun when it was fired, killing several German marines.[38]

Collaboration

Joining the German Army

No islanders joined active German military units.[39]

British Freikorps

Eric Pleasants, a British seaman, met up with Dennis Leister, an Englishman of German extraction who had gone to Jersey as part of the Peace Pledge Union party. They took to burglary of houses left unoccupied by families that had evacuated. In 1942, they were sentenced by the German military court for a number of offences and sent to Dijon to serve their sentences. They returned to Jersey on their release in February 1943, but were deported as undesirables to Kreuzberg in Germany.[39] They both joined the British Free Corps (Britisches Freikorps) a unit of the Waffen SS, which comprised at its peak just 27 men.[40] Pleasants ended up at large in Soviet-occupied Berlin until he was caught in 1946 and sent to a prison in Siberia. He was repatriated in 1952. Leister was jailed by British courts for three years.

Working for the Nazi regime

Eddie Chapman, an Englishman, was in prison for burglary in Jersey when the invasion occurred. Chapman and fellow prisoner Anthony Faramus a Jerseyman, offered to work for the Germans as spies. They were arrested by the Germans and sent to Fort de Romainville France. Faramus was rejected and sent to Buchenwald concentration camp; he would survive the war. Chapman was accepted by the Abwehr and, under the code name Fritz, trained as a spy. On landing in Britain, he turned himself in to the authorities and became a British double agent under the code name ZigZag,[41]:120 ending the war with an Iron Cross from Hitler, a British pardon and £6,000 from MI5.[42]

Pearl Vardon, a Jersey-born teacher, spoke German and worked for an Organisation Todt company as an interpreter. After entering into a relationship with a Wehrmacht officer, Oberleutnant Siegfried Schwatlo, when he was posted to Germany in 1944, she decided to go with him. Vardon began working as an announcer at Radio Luxembourg for the Deutsche Europa Sender (DES). She read out letters written by British prisoners-of-war to their families back home. A German colleague later said of Vardon's attitude that she "simply hated all things English and loved all things German".[43] Vardon was tried at the Old Bailey in February 1946.[44] There she pleaded guilty to the offence of "doing an act likely to assist the enemy" and was given a nine-month prison sentence.

John Lingshaw from Jersey was deported to Oflag VII-C in Laufen in 1942. In August 1943 he volunteered and was employed to teach English to a group of 15 women working in the German propaganda service.[45] After the war he was prosecuted in the Old Bailey and sentenced to five years’ penal servitude.[46]

Fraternisation

Some island women fraternised with the occupying forces. This was frowned upon by the majority of islanders, who gave them the derogatory nickname "Jerry-bags".[11]:201 The extent of "horizontal collaboration" has been exaggerated.[10] Records released by the Public Records Office in 1996 suggest that as many as 900 babies of German fathers were born to Jersey women during the occupation.[47] The Germans themselves estimated their troops had been responsible for fathering 60 to 80 illegitimate births in the Channel Islands.[10]

Following liberation, the Security Service calculated a figure of 320 illegitimate births in the islands, estimating that of those 180 were due to German fathers.[11]:201 The majority (95 per cent) of women did not have relationships with Germans.[1]:236 The German military authorities themselves tried to prohibit sexual fraternisation in an attempt to reduce the transmission of sexually transmitted diseases. They opened brothels for soldiers and OT workers, staffed mainly by French prostitutes, who were able to earn a good income, under German medical supervision.[24]:181

There were very few cases of maltreatment of the island women or their children during the war, as there was always the risk of being informed on; however, some were sent postcards saying "you are number X on the list for a haircut". Local girls seen out with Germans after the curfew were arrested for breach of the curfew law.[23]:291 After liberation, attempts to abuse the girls were defused by the police and British soldiers.[2]:130 Some girls were helped to leave the islands as soon as possible.[48]:69 A number of German soldiers returned and married their island sweethearts.[2]:212

Friendships

Being civil to each other was expected by both sides. Germans attended islanders' cricket matches, and cinemas were divided with separate areas allocated to Germans and civilians.[24]:180 The German army regularly put on music concerts open to the public. Dances were held, with local ladies invited to attend. A few families became friendly with a specific soldier or OT worker. More than 20 Spanish Republican OT workers stayed and married Jersey women after the war.[11]:200

Men and older women, as well as young girls, became friends with Germans. A complete mix were caught out after curfew with soldiers.[23]:274

Baron von Aufsess, a very senior German commander in Jersey was out walking when he came across a woman and her daughter collecting wood, which was illegal. He recognised them and, surprisingly, carried their bundle of firewood back to their house and was invited in for a cup of tea. Thereafter the Baron became a regular visitor, with musical evenings enjoyed by all three.[6]:124

The British commander after the liberation heard evidence from many people of collaboration. Talks of "lobster dinners" for Germans were dismissed, as were most other accusations as hearsay, second-hand accounts and "tittle tattle".[6]:274

Informers

There were a number of cases of anonymous letters sent to the German authorities denouncing fellow islanders for crimes. The reasons for these letters may well be personal rather than acts of collaboration. A few letters were intercepted by the post office, the head of whom steamed open the envelopes and having read the contents, "lost" the letters or delayed them until the accused could be warned.[23]:224 Other letters were not anonymous, as people were attracted by the 20–50 German Reichsmark reward offered to informers by the Germans.[1]:254 On Sark, an islander nailed to a tree a list of everyone with an illegal radio; the local commandant was shocked by this betrayal and refused to act on the information.[49]:161

People were arrested, imprisoned and subsequently died after being denounced. Louisa Gould was one. She had been sheltering an escaped OT slave worker. She was denounced by two "old biddies", elderly spinsters living next door who sent an anonymous letter. Though not prosecuted after the war, the old ladies were ostracised for the rest of their lives.[6]:185 Informers were hated more than the Germans by the civilian population.[28]:43

Relief of civilians

In August 1944, the German Foreign Ministry made an offer to Britain, through the Swiss Red Cross, that would see the release and evacuation of all Channel Island civilians except for men of military age. The British considered the offer, a memorandum from Winston Churchill stating "Let 'em starve. They can rot at their leisure", it is not clear whether Churchill meant the Germans, or the civilians. In late September the offer was rejected.[20]:155

In November the Germans instigated a message, after getting agreement with the Bailiff of Jersey, to send to Britain details of the current level of food stocks available to the civilians. The British, with the agreement of the German authorities, then agreed to the supply of Red Cross parcels to civilians.[20]:156 It was very unusual for Red Cross POW parcels to be given to civilians.

The British Joint War Organisation (The British Red Cross and Order of St John) working with the International Committee of the Red Cross organised for the SS Vega to be released from the Lisbon-Marseilles route to bring relief to the Channel Islands. Arriving in Guernsey on 27 December and Jersey on 31 December with 119,792 standard food parcels, salt, soap and medical supplies.[20]:157 Further shiploads of relief supplies would be received monthly until liberation. These parcels saved many civilian lives.

Kommando-Unternehmen Granville

In January 1945 a plan was drafted by Generalleutenant Graf von Schmettow to hit back at the Americans occupying the Cherbourg peninsula. Using a number of ships rescued from St Malo and with the additional objective of boosting morale of German soldiers in the Channel islands a detailed plan was created using information from German prisoners who had been in Granville and stole a landing craft LCV(P) to escape. Training exercises were undertaken by 800 men in Guernsey, away from the civilian population to avoid the plans being revealed. Work on the ships also had to be kept away from the SS Vega in case the preparations were reported. An idea that a raid was being planned was noticed and a message was sent from Guernsey to France with an escaping OT worker, Xavier Gollivet, who had worked for the German Harbour Master and two local fisherman, Tom and Jack Le Page,[50]:4 it would be ignored. A false start on 6 February due to fog, also risked disclosure of the attack.

On 7 March the Palace Hotel where the raid planning was being undertaken caught fire – it might have been sabotage[51] – and to avoid calling the civilian fire brigade, who might see the attack plans inside the building, the Germans rigged it with explosives to create a fire break. However they exploded early, killing nine soldiers. The next day, on 8 March, to coincide with a spring tide, 13 ships sailed. One American patrol boat guarding the port of Granville, PC564 was alerted by a radar station that identified the convoy, but when it went to the attack, PC564 was destroyed by 88 mm shells from German ferries armed with 8.8 cm SK C/35 naval guns. No alert had been sounded in Granville and the ships carrying German troops landed almost unopposed at the French port.[20]:162–182

For several hours the 200 German troops controlled Granville harbour, damaging four ships, nine cranes and a train before leaving with one allied ship loaded with coal, 55 released German prisoners of war and 30, mainly American, prisoners;[51] some of the officers were captured in bed with local women. Allied losses were nine dead and 30 wounded. German losses being three killed, 15 wounded and one taken prisoner. A German minesweeper M412 was aground and could not be freed from the falling tide; it was destroyed using a sea mine. All other ships returned safely to Jersey. The raid was a major local success, if immaterial to the outcome of the war. It was the last major attack undertaken by German forces in the war.[20]:162–182

People in the islands

People in the islands fall into a number of main categories. Each category knew people they did not trust, others they did not like and yet others they treated as enemies:

- Within the German army were soldiers from many countries:

- Soldiers from Germany

- Soldiers from the expanded Third Reich including Austria and Poland[52]:23

- Those from the eastern countries, called Ostlegionen soldiers by the Germans, they were treated worse than ordinary soldiers and were often hungry. They lived in fear of being returned to Russia where their fate would not be good.[52]:8

- Organisation Todt workers fell into three categories:

- Volunteer experts, recruited from many countries, well paid, allowed holidays and given benefits

- Semi-volunteer workers (often given little choice about volunteering) who were paid and allowed some time off[53]

- Unskilled workers forced to work, who were badly paid, treated, clothed and fed. The worst treated become a category of slave workers, they appear in all islands but were mainly in Alderney camps

- Locals could fall into numerous categories. There were "informers", "black marketeers", those "too friendly with the enemy" those who "worked for the Germans", those who "antagonised the Germans" and lastly the category, the "normal" civilian

Locals could be OT workers, German soldiers and OT workers could also be black marketeers, any of them could be criminals and people held differing religious beliefs and differing political ideals. A few lived "underground", hidden away from sight, they might be Jews, escaped OT workers, escaped convicts including those who undertook "resistance" activities, or even soldiers. Authority was enforced by the Feldgendarmerie, the Geheime Feldpolizei and the local police.

After liberation

A conference at the Home Office decided to define collaboration as:

- (a) Women who associated with Germans;

- (b) People who entertained Germans or had social contacts with them;

- (c) Profiteers;

- (d) Information givers;

- (e) Persons, whether contractors or workmen, who had carried out work for Germans.

No official action would be taken for groups (a) and (b); social sanction was sufficient. Group (c) would be dealt with through taxation rules, the War Profits Levy (Jersey) Law 1945 and the War Profits Levy (Guernsey) Law 1946. Groups (d) and (e) would come under the provision of the Treason Act, Treachery Act or Defence Regulation 2A. The first two carried mandatory death sentences; the third, penal servitude for life.[2]:202 The British intelligence services in 1945 concluded that the numbers of English in the OT was small and that they were at least under some degree of compulsion.[30]:177

Following the liberation of 1945, allegations of collaboration with the occupying authorities were investigated. By November 1946, the UK Home Secretary was in a position to inform the House of Commons[54] that most of the allegations lacked substance. Only 12 cases of collaboration were considered for prosecution, but the Director of Public Prosecutions ruled out prosecutions on insufficient grounds. In particular, it was decided that there were no legal grounds for proceeding against those alleged to have informed to the occupying authorities against their fellow citizens.[55] The only trials connected to the occupation of the Channel Islands to be conducted under the Treachery Act 1940 were against individuals from among those who had come to the islands from Britain in 1939–1940 for agricultural work, these included conscientious objectors associated with the Peace Pledge Union and people of Irish extraction.[10]

King George VI and Queen Elizabeth made a special visit by plane to the islands on 7 June 1945.[56] Field Marshall Lord Montgomery visited in May 1947, Winston Churchill was invited twice in 1947 and 1951, but did not travel to the islands.

The bailiffs of each island were cleared of every accusation of being "Quislings" and collaborators. Both were given knighthoods for patriotic service in 1945.[7]:172 A list of other people were also honoured with knighthoods, CBE, OBE or BEM. Only those who lived under occupation can fully appreciate those five long years.[51]

The passing of laws during the occupation needed to be legalised; in Jersey 46 laws were retroactively given Royal Assent after Liberation through the adoption of the Confirmation of Laws (Jersey) Law 1945.[57]

Germans were investigated, particularly regarding the deportations; the outcome concluding that no war crimes had been committed in Jersey, Guernsey or Sark. As regards Alderney however, a court case was recommended over the ill treatment and killing of the OT slave workers there.[2]:202 No trial ever took place in Britain or Russia; two OT overseers were however tried in France and sentenced to many years of imprisonment.[6]:246

Deaths during the occupation:[7]:175–79

- German forces: about 550

- OT workers: over 700 (500 graves and 200 drowned when a ship was sunk)

- Allied forces: about 550 (504 from the sinking of HMS Charybdis and HMS Limbourne)

- Civilians: about 150, mainly air raids, deportees and in prisons (excludes Island deaths from malnutrition and the cold)

A higher percentage of civilians died in the islands per head of pre-war population than in the UK.

From the people who had left the Islands in 1939/40 and been evacuated in 1940, 10,418 islanders served with Allied forces.[1]:294

- Jersey citizens: of 5,978 who served, 516 died

- Guernsey citizens: of 4,011 who served, 252 died

- Alderney citizens: of 204 who served, 25 died

- Sark citizens: of 27 who served, one died

A higher percentage of serving people from the islands died per head of pre-war population than in the UK.

See also

References

Notes

- Mière, Joe. Never to be forgotten. Channel Island Publishing. ISBN 978-0954266981.

- Tabb, Peter (2005). A peculiar occupation. Ian Allan Publishing. ISBN 978-0711031135.

- Chapman, David. Chapel and Swastika: Methodism in the Channel Islands During the German Occupation 1940–1945. ELSP. ISBN 978-1906641085.

- Bell, William. Guernsey Occupied but never Conquered. The Studio Publishing Services (2002). ISBN 978-0952047933.

- "States vote to change 500-year-old treason law". BBC. 5 June 2014.

- Nettles, John (25 October 2012). Jewels and Jackboots (1st Limited ed.). Channel Island Publishing. ISBN 978-1905095384.

- King, Peter (1991). The Channel Islands War (First ed.). Robert Hale Ltd. ISBN 978-0709045120.

- Turner, Barry (April 2011). Outpost of Occupation: The Nazi Occupation of the Channel Islands, 1940–1945. Aurum Press (April 1, 2011). ISBN 978-1845136222.

- Cruickshank, Charles G. (1975). The German Occupation of the Channel Islands. The Guernsey Press. ISBN 0-902550-02-0.

- Sanders, Paul (2005). The British Channel Islands under German Occupation 1940–1945. Jersey: Jersey Heritage Trust / Société Jersiaise. ISBN 0953885836.

- Carre, Gilly. Protest, Defiance and Resistance in the Channel Islands. Bloomsbury Academic (August 14, 2014). ISBN 978-1472509208.

- Forty, George (2005). Channel Islands At War: A German Perspective. Ian Allan Publishing. ISBN 978-0711030718.

- Harris, Roger E. (1979). Islanders deported part 1. ISBN 978-0902633636.

- Stephenson, Charles (28 February 2006). The Channel Islands 1941–45: Hitler's Impregnable Fortress. Osprey Publishing, 2006. ISBN 9781841769219.

- Sherwill, Ambrose (April 2007). A fair and Honest Book. ISBN 978-1-84753-149-0.

- "Occupation of the Channel Islands of Guernsey and Jersey".

- Cruickshank, Charles (1975), The German Occupation of the Channel Islands, The Guernsey Press Co, Ltd., pp. 78–79. Cruickshank is the official history of the occupation; Wood, Alan and Wood, Mary Seaton (1955), Islands in Danger, London: Hodder and Stoughton, p. 82

- Bunting, Madeleine (1995), The Model Occupation: The Channel Islands under German Rule, 1940–1945, London: Harper Collins Publisher, p. 191

- Bunting, p. 316

- Fowler, Will (2016). The Last Raid: The Commandos, Channel Islands and Final Nazi Raid. The History Press. ISBN 978-0750966375.

- "POLICING DURING THE OCCUPATION 1940–1945". Guernsey Police.

- Cortvriend, V V. Isolated Island. Guernsey Star (1947).

- Bell, William. I beg to report. Bell (1995). ISBN 978-0952047919.

- Cruickshank, Charles (2004). The German Occupation of the Channel Islands. The History Press; New edition (30 Jun. 2004). ISBN 978-0750937498.

- Coles, Joan. Three years behind barbed wire. La Haule Books. ISBN 086120-008-X.

- The Organisation Todt and the Fortress Engineers in the Channel Islands. CIOS Archive book 8.

- Le Page, Martin (1995). A Boy Messenger's War: Memories of Guernsey and Herm 1938–45. Arden Publications (1995). ISBN 978-0952543800.

- Briggs, Asa (1995). The Channel Islands: Occupation & Liberation, 1940–1945. Trafalgar Square Publishing. ISBN 978-0713478228.

- Chapman, David. Chapel and Swastika: Methodism in the Channel Islands During the German Occupation 1940–1945. ELSP. ISBN 978-1906641085.

- Handbook of the Organisation Todt - part 1. Military Intelligence Records Section, London Branch. May 1945.

- Stroobant, Frank (1967). One Man's War. Guernsey Press.

- "HISTORY OF THE GUERNSEY POLICE". Guernsey Police.

- Le Tissier, Richard (May 2006). Island Destiny: A True Story of Love and War in the Channel Island of Sark. Seaflower Books. ISBN 978-1903341360.

- "In Prison in Guernsey during the German Occupation". BBC. 13 September 2005.

- Turner, Barry (April 2011). Outpost of Occupation: The Nazi Occupation of the Channel Islands, 1940–1945. Aurum Press (April 1, 2011). ISBN 978-1845136222.

- Charybdis Association (1 December 2010). "H.M.S. Charybdis: A Record of Her Loss and Commemoration". World War 2 at Sea. naval-history.net. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- Rückzug (Retreat), Joachim Ludewig, Rombach GmbHm, Freiburg im Breisgau, 1991, Eng. trans. © 2012 The University Press of Kentucky, ISBN 978-0-8131-4079-7, pp. 37–41.

- Strappini, Richard (2004). St Martin, Guernsey, Channel Islands, a parish history from 1204. p. 144.

- Ginns, Michael (2009). Jersey Occupied: The German Armed Forces in Jersey 1940–1945. Channel Island Publishing. ISBN 978-1905095292.

- "The British Free Corps".

- Hinsley, F. H. & C. A. G. Simkins (31 August 1990). British Intelligence in the Second World War: Volume 4, Security and Counter-Intelligence. Cambridge University Press, 1990. ISBN 9780521394093.

- Booth, Nicholas (2007). Zigzag: The Incredible Wartime Exploits of Double-agent Eddie Chapman. Arcade Publishing. ISBN 9781559708609.

- David Pryce-Jones (2011). Treason of the Heart: From Thomas Paine to Kim Philby. Encounter Books. p. 173. ISBN 9781594035289. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- "Records of the Central Criminal Court CRIM 1/1761". The National Archives. 26 February 1946. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- Madeleine Bunting (1995). The Model Occupation: The Channel Islands Under German Rule 1940–1945. Harper Collins. p. 143. Retrieved 2012-12-31.

- "FOREMAN HELPED ENEMY", The Advocate, March 2, 1946, retrieved 2012-12-31

- Moyes, Jojo (1996-11-23). "How Jersey's Nazi children disappeared". London: The Independent.

- Lewis, John (1997). A Doctor's Occupation. Starlight Publishing (1997). ISBN 978-0952565918.

- Cooper, Glynis (January 2008). Foul Deeds and Suspicious Deaths in Jersey. Casemate Publishers, 2008. ISBN 9781845630683.

- Toms, Carel (2003). St Peter Port, People & Places. ISBN 1-86077-258-7.

- Lempriére, Raoul. History of the Channel Islands. Robert Hale Ltd. p. 226. ISBN 978-0709142522.

- Channel Islands Occupation Review No 37. Channel Islands Occupation Society.

- Channel Islands Occupation Review No 39. Channel Islands Occupation Society. p. 36.

- Hansard (Commons), vol. 430, col. 138.

- The German Occupation of the Channel Islands. Cruickshank, London. 1975. ISBN 0-19-285087-3.

- "Liberation stamps revealed". ITV News. 29 April 2015.

- Duret Aubin, C.W. (1949). "Enemy Legislation and Judgments in Jersey". Journal of Comparative Legislation and International Law. 3. 31 (3/4): 8–11.

Bibliography

- Bell, William M. (2002), "Guernsey Occupied But Never Conquered", The Studio Publishing Services, ISBN 978-0952047933.

- Carre, Gilly, Sanders, Paul, Willmot, Louise, (2014), Protest, Defiance and Resistance in the Channel Islands: German Occupation, 1940–45, Bloomsbury Academic, ISBN 978-1472509208.

- Cruickshank, Charles (2004), "The German occupation of the Channel Islands", The History Press, ISBN 978-0750937498.

- Faramus, Anthony, (1990) Journey Into Darkness. Foreword by Greville Janner. Grafton. ISBN 978-0-246-13490-5.

- King, Peter (1991), “The Channel Islands War 1940–1945”, Robert Hale Limited, ISBN 978-0709045120.

- Macintyre, Ben, (2007) Agent Zigzag. Bloomsbury, ISBN 0-7475-8794-9.

- Mière, Joe (2004), "Never to Be Forgotten", Channel Island Publishing, ISBN 978-0954266981.

- Nettles, John (2012), Jewels & Jackboots, Channel Island Publishing & Jersey War Tunnels, ISBN 978-1-905095-38-4.

- Sanders, Paul (2005), “The British Channel Islands under German Occupation 1940–1945” Jersey Heritage Trust / Société Jersiaise, ISBN 0953885836.

- Tabb, Peter (2005), A peculiar occupation, Ian Allan Publishing, ISBN 0-7110-3113-4.