Philippine National Railways

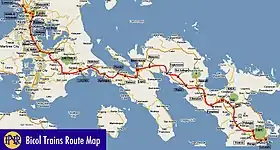

The Philippine National Railways (PNR) (Filipino: Pambansang Daambakal ng Pilipinas and Spanish: Ferrocarril Nacional de Filipinas) is a state-owned railway company in the Philippines which operates one commuter rail service between Metro Manila and Laguna, and local services between Sipocot, Naga City and Legazpi City in the Bicol Region.[1] It is an attached agency of the Department of Transportation.

.svg.png.webp) | |

Network map, showing both active and inactive lines. North Main Line (Northrail) is colored green and the South Main Line (Southrail) in orange. | |

(2015-0815).JPG.webp) A Hyundai Rotem DMU and a class 900 locomotive near Santa Mesa Station | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Stations operated | 138 |

| Parent company | Department of Transportation |

| Headquarters | Tutuban, Tondo, Manila |

| Locale | Luzon |

| Dates of operation | November 24, 1892 (as Ferrocarril de Manila-Dagupan) June 20, 1964 (as Philippine National Railways)– |

| Predecessors | Manila Railway Company (d/b/a Ferrocarril de Manila a Dagupan) Manila Railroad Company (MRR) |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge |

|

| Electrification | 1500 V DC overhead lines (by 2023) |

| Length |

|

| Operating speed | 40–90 km/h (25–56 mph) |

| Other | |

| Website | www |

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Industry | Rail transport |

|---|---|

| Founded | November 24, 1892 (as Ferrocarril de Manila-Dagupan) June 20, 1964 (as Philippine National Railways) |

| Headquarters | , |

Area served | Metro Manila Calabarzon Bicol Region |

Key people | Roberto T. Lastimoso Chairman Junn Magno, General Manager |

| Services | Current: Commuter rail Suspended[a]: Inter-city rail Freight services |

| Owner | Government of the Philippines under Department of Transportation |

| Website | pnr.gov.ph |

PNR began operations on November 24, 1892 as the Ferrocarril de Manila-Dagupan, during the Spanish colonial period, and later becoming the Manila Railroad Company (MRR) during the American colonial period. It became the Philippine National Railways on June 20, 1964 by virtue of Republic Act No. 4156. PNR used to operate over 1,100 km (684 mi) of route from La Union to the Bicol Region.[2] However, neglect reduced PNR's service. Persistent problems with informal settlers in the 1990s contributed further to PNR's decline. In 2006, Typhoons Milenyo and Reming caused severe damage to the network, resulting in the suspension of the Manila-Bicol services. In 2007 the Philippine government initiated a rehabilitation project aiming to remove informal settlers from the PNR right of way, revitalize commuter services in Metro Manila, and restore the Manila-Bicol route as well as lost services in Northern Luzon. In July 2009, PNR unveiled a new corporate identity and inaugurated new rolling stock. Long-distance Bicol services resumed in June 2011, but were suspended again in October 2012, leaving only local service between Naga and Sipocot.[3] Local service between Naga and Legazpi resumed in October 2015.[4]

History

Spanish period

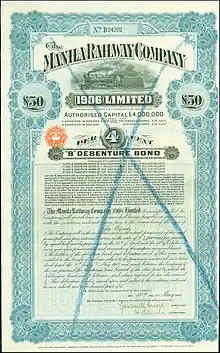

On June 25, 1875, under a royal decree issued by King Alfonso XII of Spain, the required Inspector of Public Works of the Philippine Islands was requested to submit a railway system plan for Luzon. The plan, which was submitted five months later by Don Eduardo Lopez Navarro, was entitled Memoria Sobre el Plan General de Ferrocarriles en la Isla de Luzón, and was promptly approved. A concession for the construction of a railway line from Manila to Dagupan was granted to Don Edmundo Sykes of the Ferrocarril de Manila–Dagupan (Manila–Dagupan Railway), later to become the Manila Railway Company, Ltd. of London, on June 1, 1887.[5][6]

The Ferrocarril de Manila–Dagupan, which constitutes much of the North Main Line today, began construction on July 31, 1887 with the laying of the cornerstone for Tutuban station, and the 195-kilometer (121 mi) line opened on November 24, 1892. Expansion of the Philippine railway network would not begin until the American colonial period, when on December 8, 1902, the Philippine Commission passed legislation authorizing the construction of another railway line, which would later form the South Main Line.

American period

Additional legislation was passed in 1909 authorizing further railway construction and the use of government bonds to finance them, and by 1916, 792.5 kilometers (492.4 mi) of track had been built by the company, which had reorganized itself as the Manila Railroad Company of New Jersey (MRR).[7] Apart from the North and South Main Lines, other lines branching out of these two main lines were built, like the lines to Rosales and San Quintin, Pangasinan; San Jose and Cabanatuan, Nueva Ecija; Dau, Carmen, Floridablanca and Arayat, all in Pampanga province, as well as inside the US Air Base Fort Stotsenburg which became Clark Air Base; Antipolo, Taytay, and Montalban, a spur line to Nielsen Field in what is now Ayala Avenue in the Makati Financial District from Culi Culi (now Pasay Road) Station, all in Rizal province; Cavite City and the nearby US Air Base of Sangley Point as well as Noveleta and Naic, both in Cavite province; Canlubang, Santa Cruz and Pagsanjan all in Laguna province; Batangas City and Bauan both in Batangas province, as well as a line connecting San Pablo City in Laguna to Luta (later Malvar) in Batangas province (this used to be part of Main Line South until a shorter cut-off line connecting Los Banos on the Santa-Cruz/Pangsanjan line to San Pablo was opened); Port Ragay in the Bicol province of Camarines Sur; as well as till Tabaco from Legaspi, Albay.

Similar to other railroads at the time, the Manila Railroad Company suffered from financial difficulties during World War I, and on February 4, 1916, the Philippine Assembly passed Act No. 2574, authorizing the Governor-General to negotiate for the nationalization of the MRR's assets. The MRR was eventually nationalized in January 1917, with the Philippine government paying ₱8 million to the company's owners and assuming ₱53.9 million in outstanding debt. Consequently, the MRR's management shifted from British to American hands, and in 1923, José Paez became the first Filipino general manager.[7]

During the 1920s, the MRR embarked on a general program of improvements as a result of operating surpluses accrued over much of the decade. The ₱30 million program allowed for the extension of railway service on the North Main Line from Dagupan to San Fernando in La Union, the extension of the South Main Line to Legazpi in Albay, and the construction of several spur lines. The last rail connecting Manila to Bicol was laid on November 17, 1937 and regular direct service between Manila and Legazpi was inaugurated on May 8, 1938, and by 1941, the MRR operated 1,140.5 kilometers (708.7 mi) of track.[7]

On December 14, 1941, at the start of World War II, the MRR was put under U.S. military control, and on December 30, the MRR management was ordered to allow U.S. military forces to destroy network infrastructure, resulting in very extensive damage to train facilities and right of way. Coupled with further damage during the Japanese occupation of the Philippines, where the Imperial Japanese Army operated services on a very limited basis using whatever could be salvaged, and further fighting in the Allied liberation of the Philippines by the combined American and Filipino forces a few years later, damages to railroad property amounted to around ₱30 million.[7] By the end of the war, only 452 kilometers (281 mi) were operational,[5] largely as a result of the United States Army and the Philippine Commonwealth Army performing temporary repairs on railroad infrastructure for military purposes. MRR property was later returned to the Philippine government on February 1, 1946.[7]

Post-war period

Following the war, the MRR was able to restore limited services, using surplus military equipment and payments made by the United States Army and the Philippine Commonwealth Army for use of railway facilities in the Philippines Campaign. By July 1, 1947, funded by a ₱20 million rehabilitation allocation set aside by the Philippine government, around 75% of the entire railway network prior to 1941 was rehabilitated. By 1951, with the MRR receiving ₱3 million in war reparations funds, 941.9 kilometers (585.3 mi) of track, representing 82.5% of the total railway network prior to 1941, was in operation.[7] Later in the 1950s, the MRR fleet of locomotives was converted from steam to diesel engines, and the company was given a new charter under Republic Act No. 4156, becoming the modern-day Philippine National Railways.

Creation of PNR

Natural calamities such as the 1973 and 1975 floods disrupted services and forced the closure of several parts of the main lines. On July 23, 1979, President Ferdinand Marcos issued Executive Order No. 546, which designated the Philippine National Railways as an attached agency of the then Department of Transportation and Communications.[5]

In 1988, during the administration of Corazon Aquino, the North main line was closed, with trains unable to reach various provinces in the country. The South main line was also closed due to typhoons and floods, and the eruption of Mayon Volcano in 1993, in which ash flows and lava destroyed the rail line and its facilities. However, jeeps, buses and taxis were popular, and many people were swayed from the present service until 2009.

When Fidel V. Ramos succeeded Corazon Aquino, he decided to rehabilitate the South Main Line from Tutuban to Legaspi, and appointed Jose B. Dado as the new PNR general manager. A railway system running from Manila to Clark was also set to be constructed in the 1990s, when Ramos signed a memorandum of agreement with Juan Carlos I of Spain for its construction in September 1994, but the project was later cancelled due to disagreement on the source of funding.[8]

Rehabilitation attempts and the NorthRail project

The administration of Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo actively pursued the rehabilitation of the Philippine National Railways through various investments and projects designed to revive Philippine rail transport,[5][9][10] despite the numerous problems involved. Total reconstruction of rail bridges and tracks, including replacement of the current 35-kilogram (77-pound) track with newer 50-kilogram (110-pound) tracks[10] and the refurbishing of stations, were part of the rehabilitation and expansion process. The first phase, converting all the lines of the Manila metropolitan area, were completed in 2009.[10] On July 14, 2009, Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo presided over the launch of the new diesel multiple units from Hyundai Rotem for the Philippine National Railways. As part of its new image, a new brand name, PNR Filtrack was added and a new PNR logo was unveiled until the succeeding administration decided to revert to the original logo.[11]

The San Cristobal bridge in Calamba, Laguna was rebuilt in May 2011. The Bicol Express train service was inaugurated on June 29, with a maiden voyage between Manila and Naga City plus a return trip back to the terminus on July 1. This inaugural trip was marred by the collapse of the embankment at Malaguico, Sipocot. It was discovered before the train passed through and was repaired. The restored Bicol Express intercity service was offered on a daily basis, running mostly during night time.

The Northrail project involved the upgrading of the existing single track to an elevated dual-track system, converting the rail gauge from narrow gauge to standard gauge, and linking Manila to Malolos City in Bulacan and further on to Angeles City, Clark Special Economic Zone, the Clark International Airport. The railway project was contracted out by the Arroyo administration in 2003 to China National Machinery and Equipment Corporation (CNMEC) for an original cost of $421 million.[12] This project was estimated to cost around US$500 million, with China offering to provide some US$400 million in concessionary financing.[13] Construction of the railway was halted, then temporarily continued in January 2009, and then stopped again in March 2011, due to a series of anomalies with the foreign contractor,[14] before finally being scrapped in 2011 by the Aquino administration on lingering legal issues and corruption allegations.

The DOTC has examined reviving the project by commissioning a feasibility study by CPCS Transcom Ltd. of Canada. Part of the study examined having a Malolos-Tutuban-Calamba-Los Baños Commuter Line.[15][16]

Current developments

The Philippine National Railways is currently working to rehabilitate its defunct norther railway line with the establishment of the North-South Commuter Railway, from New Clark City to Metro Manila.[17] Also in the pipeline is the rehabilitation of the current South Commuter line, and the reestablishment of long-haul services to the south. Rehabilitation of tracks and stations has commenced.

After nearly 20 years, PNR reopened the Metro North Commuter line, and launched the Caloocan-Dela Rosa shuttle line, on August 1, 2018.[18][19] This would be followed by a steady expansion and reintroduction of rail services to the north, currently reaching to Malabon City, which has not seen rail activity for nearly 20 years. A plan to reactivate the Carmona line was bared as well,[20] and the revival of cargo rail from Port Area, Manila to Laguna is now being planned.[21][22]

On December 16, 2018, all commuter services saw changes in train runs[23] and establishments of new termini, particularly in the recently revived Metro North Commuter. More train runs were added for the north currently terminating at Governor Pascual.[24]

On November 16, 2018, PNR became a provisional member of International Union of Railways.[25]

On May 21, 2019, DMCI won the contract for the construction of PNR North 1.[26]

On June 14, 2019, PNR became ISO-certified (ISO 9001:2015) for railway repair, rehabilitation, restoration and maintenance, train control and rolling stock maintenance, station operation and other related services. The certification was announced on October 2, 2019.[27]

Operations and services

The PNR currently operates in Metro Manila and the neighboring Laguna province. At the last years of regular intercity service along the system's entire length in the late 1980s, it served from Tutuban to San Fernando, La Union on the North Main Line and Legazpi, Albay on the South Main Line. Various branch lines also led to Batangas, Cavite, Nueva Ecija, Rizal and Tarlac. One of the branch lines that led to Carmona was intended to be reopened by 2019. This was not realized as of March 2020.

Summary of services

| Service | Terminus | Status | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metro South Commuter (MSC) | Tutuban | Alabang | Operational |

| Tutuban | Mamatid | Operational | |

| Tutuban | Calamba | Operational | |

| Tutuban | IRRI (UP Los Baños) | Operational | |

| Metro North Commuter (MNC) | Tutuban | Governor Pascual | Operational |

| Tutuban | Valenzuela | Planned | |

| Shuttle Service (SS) | Governor Pascual | FTI | Operational |

| Valenzuela | FTI | Planned | |

| Dela Rosa | Carmona | Planned | |

| Tutuban | Sucat | Discontinued | |

| Santa Mesa | Sucat | Discontinued | |

| Alabang | Calamba | Planned | |

| Premiere Train | Tutuban | Mamatid | Discontinued |

| Bicol Commuter (BCT) | Tagkawayan | Naga | Suspended |

| Sipocot | Naga | Operational | |

| Naga | Legazpi | Operational | |

| Bicol Express (BEx) | Tutuban | Naga | Suspended |

| Tutuban | Ligao | Suspended | |

| Mayon Limited Deluxe (MLD) | Tutuban | Ligao | Discontinued; replaced by ILE |

| Mayon Limited Ordinary (MLO) | Tutuban | Ligao | Discontinued; replaced by ILE |

| Isarog Limited Express (ILE) | Tutuban | Naga | Suspended |

Metro Commuter Line

Metro North Commuter

The reactivated Metro North Commuter ran initially from Caloocan to Makati and uses a single special fare matrix of PHP 12.00 for ordinary, and PHP 15.00 for air-conditioned. This was later extended to reach FTI in Taguig, now with a distance-based fare matrix. A Caloocan-Tutuban shuttle service also exists, using the original right-of-way once used for the Dagupan line. Originally terminating at 10th Avenue station while the historical Caloocan station was still being prepared for activation,[28] the station now terminates at its originally intended station since September 10.

DOTr and PNR are also working on reviving and reactivating rail services in areas prepared for NorthRail, such as Malabon and possibly Valenzuela. First proposed and planned last September 2018,[29] the extension to Gov. Pascual Avenue and the re-establishment of the Governor Pascual Station (formerly called Acacia Station) in Malabon has been done, with new rail ties and narrow gauge rail tracks being restored.[30] It reopened to the public on December 3, 2018.

Another extension, this time targeting Valenzuela City (likely Polo area) has been bared on August 14, 2019, and will require rebuilding a railroad bridge crossing Tullahan river that has been previously destroyed.[31]

The line is provisional and services will be potentially interrupted when the elevated tracks are to be constructed, likely after the construction of NLEX Segment 10.1. The reconstructed lines are targeted for freight use as well as part of the system's extension to the north.

Metro South Commuter

The Metro Commuter (also known by then-remaining active service MSC or Metro South Commuter),[32] which was formerly called Commuter Express (also Commex), serves as the commuter rail service for the Manila metropolitan area, extending as far south as Calamba City and Los Baños, both in Laguna. The PNR uses GE locomotives such as 900 Class, 2500 Class, and 5000 Class hauling Commex passenger cars as well as newly procured 18 (3 car trains, 6 sets) Hyundai Rotem DMUs and KiHa 52 for this service. 203 series EMUs are now also used for Metro Commuter runs. MSC service using the new DMUs, KiHa 52, KiHa 350 and 203 series EMUs is currently offered between Tutuban and Alabang in Muntinlupa City. Currently, MSC makes 42 return services, 21 in each direction.[33]

Shuttle Service

The Shuttle Service is a commuter rail service initially introduced on January 27, 2014. This service used Hyundai Rotem DMUs and JR KiHa 52. There were 2 routes of the Shuttle Service, where trains stop at all stations along the routes: Tutuban – Sucat and Santa Mesa – Sucat. This train service ended May 23, 2014 to conduct maintenance on the rolling stocks and due to the consecutive three weeks of delays and cancellations of this train service.

Formerly, plans for a third route plying Alabang – Calamba was to be introduced sometime in 2017. This service would use the reliveried two-car KiHa 350; This did not push through in 2018. However, with the commissioning of the new DOST Hybrid Train in 2019, this route is now under test run, currently free of charge, but with limited schedules.[34]

In 2018, a new shuttle line was introduced with the 10th Avenue – Dela Rosa route beginning August 1, as part of the renovation of the line and the return of train services to Caloocan City. The revived train service had its first extension towards Sangandaan, the original Caloocan station since September 10, extending through FTI.[35] The latest so far is the northwards extension to Governor Pascual (formerly called Acacia) in Malabon City since December 3, 2018.[36]

A new shuttle line leading to the once-abandoned Carmona branch line is planned for reopening in 2019, and will originate from the Dela Rosa station in Makati City.[37]

Bicol Commuter

The Bicol Commuter service is a commuter rail service in the Bicol Region, between stations in Tagkawayan, Quezon, and Legazpi, Albay, with Naga City in Camarines Sur acting as a central terminal. The service was launched on September 16, 2009, in time for the feast of Our Lady of Peñafrancia in Naga City.[11] The trains made seven trips a day, alternating between Tagkawayan, Sipocot, Naga City and Legazpi. All services used KiHa 52 in revised blue livery.

After further reductions, only the service between Naga and Sipocot was operating as of December 2013.[3] Service resumed between Naga and Legazpi in October 2015 with one train a day.[4]

Definitive plans to restore the entire route from Sipocot, Naga and Legazpi were bared with an inspection trip from Tutuban on September 20 with a rerailment crew, including certain areas of Quezon Province, in preparation of the restoration of more routes previously suspended.[38] As of July 15, 2020, the service has a daily ridership of 400 to 600, with a low ridership implied due to the COVID-19 community quarantines in the Philippines limiting the capacity of trains to 20%.[39]

Defunct services

Intercity services

PNR's intercity operations on its two main lines in Luzon have been indefinitely suspended since 2014.

The South Main Line then served as the primary intercity service after the permanent closure of the northern line in 1991. However, PNR also ended its regular intercity services in 2006 due to natural disasters and poor track conditions, although the Bicol Express ran irregularly between 2009 and 2014. In Camarines Sur, liquefaction of the track's embankment caused a section of the line in Sipocot to sink. This allowed the inaugural service of the new Bicol Express in 2011 to slow down to a near-stop while passing through the area.[40]

There are plans to revitalize both lines. The North Main Line is currently reserved for building the fully-elevated portion of the North–South Commuter Railway to Capas, Tarlac. The South Main Line is planned to be rebuilt and extended to Matnog, Sorsogon. The spur line to Batangas City will also be rebuilt. Test runs along the South Main Line were conducted in September 2019. On September 21, 2019, a KiHa 59 and a rerailment train consisting of a newly repainted PNR 900 class locomotive and a CMC coach conducted a test run from Tutuban to Naga.[41]

North Main Line services

The North Main Line was first opened when the Manila–Dagupan Railway was opened in 1892. At its height between the 1950s and 1960s, the line once boasted full double-track railways from Tutuban to Dagupan and also served until San Fernando, La Union. It also had branch lines to various areas in Central Luzon. However, its services severely deteriorated in the 1980s. All regular operations outside Metro Manila ended in 1988.[42] However, there was irregular service to Meycauayan railway station until all stations in Central Luzon were closed by the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo.[43]

Amianan Express

The Amianan Express was a night train service that opened in 1974. It left Manila by 11 PM and arrived in San Fernando by 4:30 AM the next day. It was serviced by then-new PNR 900 class diesel-electric locomotives and five coaches capable of seating 912 people. After ending in San Fernando station, commuters would take the bus to Ilocos Norte and Sur, and Benguet. Later, it was expanded into two services, the Amianan Day Express and the Amianan Night Express. The Amianan Night Express ran faster than its day counterpart, the Amianan Day Express, making the 260 km (160 mi) run to San Fernando, La Union in five hours.[44]

Baguio train-road service

The difficulty of terrain to build new train lines prevented both MRR and PNR to have direct train services to Baguio City. Instead, they had two luxury train services then will be accompanied by either bus or car to Baguio, and an ordinary train-bus service. During the Commonwealth era, then-MRR operated a train-bus service to Baguio. Passengers would ride the train to either Dagupan or San Fabian in Pangasinan then take the bus to Baguio City. The first service was terminated during World War II. A second service was inaugurated by the MRR by around 1955. First-class passengers would ride the train from Tutuban to Damortis station in Santo Tomas, La Union, then will ride a limousine service of Chevrolet Bel Airs to Pines Hotel in Baguio City. It costed ₱45 (equivalent to $217 in 2020 US Dollars) for this package.[45] Another service was opened during the PNR era with a bus service leading to Baguio City, with buses provided by Hino Motors. This service operated until all provincial services on the North Main Line were suspended by 1988.[46]

Dagupan Express

The Dagupan Express opened on February 10, 1979. It was serviced by CMC-300 class diesel multiple units. Like the Amianan Express, the Dagupan Express also ended in the 1980s after all North Main Line services terminated in Tarlac.[47]

Ilocos Express

The Ilocos Express was inaugurated on March 15, 1930. The services includes a dining car with catering provided by the Manila Hotel. Another variant of the service was the Baguio-Ilocos Express. Following the modernization program of the Manila Railway Company in 1955, the Ilocos Express featured a 7A class "De Luxe" coach until 1979, when the lack of operable air-conditioned coaches caused a switch to a "Tourist"-class coach. The company also operated the Paniqui Express in the 1930s, but that was eclipsed by the Ilocos Express. There were two accidents involving the service, one in 1939 and another in 1959.[48]

Ilocos Special

The fastest train operated by the PNR on the North Main Line was the Ilocos Special (Train 26). The service started in 1973. This diesel multiple-unit (DMU) train took four hours to run the 195 kilometer portion between Manila and Dagupan City.

South Main Line services

Intercity services on the South Main Line ran between Manila and Legazpi between 1916 and 2014, including the intermittent Bicol Express and Mayon/Isarog Limited services between 2009 and 2014. The services also briefly extended to Sorsogon in the 1960s due to the trains' popularity as a form of transportation with the masses.[49]

Bicol Express

Bicol Express started operations between Manila and Aloneros station in Guinayangan, Quezon by 1919 along with the Lucena Express. A separate train between Pamplona and Tabaco, and between Port Ragay and Legazpi was opened by 1933. The Tabaco branch line during this era was closed in 1937 and instead, they linked these three sections into a single line. This formed the backbone of the South Main Line and was subsequently opened in 1938. This service was short lived and ended during the Japanese occupation of the Philippines in 1942. During this era, the Japanese government focused on rebuilding the North Main Line instead and extended it to Sudipen on the border between Ilocos Sur and La Union, and the south line's rehabilitation was cut to San Pablo, Laguna.[50]

After the line's post-war rehabilitation, another service was opened. The service immediately became popular with the public and more services were introduced on August 16, 1954. There are two services of this type: the daytime Bicol Express and the Night Express which was the night train counterpart. The Bicol Express leaving Manila was numbered 511 and its night counterpart leaving Legazpi was numbered 513. The Bicol Express leaving Legazpi was numbered 512 and the Night Express leaving Manila was numbered 514. The trains only stopped at six stations between Tutuban and Legazpi: Paco, Lucena, Tagkawayan, Sipocot, Naga and Ligao. Journey times lasted 13 hours between the two termini.[51] Services were expanded until the 1970s.

By 1998, Bicol Express was the only intercity service on the South Main Line. More stations were also added into the line. It was renumbered as Train T-611 for the southbound (MA-NG) and Train T-612 for the northbound (NG-MA). Another Bicol Express train was serviced by the second version of the General Manager's train, a trainset based on modified CMC-300 series DMUs already operating in PNR service. This was numbered T-577.[52]

Since then, the service was discontinued by 2006 after natural disasters did serious damage to the tracks and bridges. Efforts to revive the service were unsuccessful. Since 2014, operations to the Bicol Region have been suspended.[53] This is primarily because of typhoon damage to bridges. The PNR hoped to reopen the Bicol Express Service by about September 2014.[54] Due to the damages brought by the Typhoon Rammasun (locally named Glenda), PNR announced that the Bicol Express' resumption of services would be further delayed until October and November 2014. Since then resumption of service has been repeatedly announced and then cancelled, most recently in late 2016.[55] This was mostly because of the remoteness of the areas and the necessity of more extensive railway repairs, which has rendered the railways towards Tutuban and back impassable until very recently.[38]

It has been decided in 2019 that the Bicol Express on its present infrastructure will be discontinued permanently and a new service to Bicol will be announced after the new standard gauge line has been completed by 2021. This line will be built with Chinese funding and the trains will be served by diesel multiple units from CRRC Zhuzhou Locomotive.[56][57]

Lucena Express

The Lucena Express was first opened in 1916 with a service between Malvar, Batangas and Aloneros in Guinayangan, Quezon. Later, the service was opened between Manila and Lucena. This train stopped at Blumentritt (San Lazaro), Santa Mesa, Paco, San Pedro, Biñan, Santa Rosa, Calamba, Los Baños, College, Masaya, San Pablo, Tiaong, Taguan, Candelaria, Lutucan and Sariaya stations. It was discontinued in 1942 during the Japanese occupation and was later integrated with the Bicol Express after the war.

Mayon Limited

In March 2012, another train service, the resurrected Mayon Limited, ran between Tutuban and Ligao. The train ran as Mayon DeLuxe on Monday, Wednesday and Friday from Tutuban as train T-713 with three air-conditioned carriages with reclining seats. The train returned on Tuesday, Thursday and Sunday as train T-714 from Ligao. On Tuesdays, Thursdays and Sundays the train ran as Ordinary train (T-815) with non-reclining seats and cooling by fan. The departure as train T-816 was every Monday, Wednesday and Friday. The train did not run on Saturdays.[58] The trains meet at Gumaca.[59] As of September 2013, all operations to the Bicol Region, including the Mayon Limited, have been suspended.[53]

The original Mayon Limited service decades ago was hauled alternatively by French Alstom locomotives Series 1500 (which had engineer operator cabs at both ends and therefore did not require being turned around at neither wyes nor turntables at the end of their trips), and General Electric locomotives, especially the U12C Series 1000, UM12C Series 2000, and U14/15C Series 900 and ran northward from Legazpi up the steep gradient leading to Camalig in the foothills of the Mayon Volcano with another locomotive pushing from the rear. The service was assigned as (Train T-577) and was considered then as the fastest and the most modern train of the Philippine National Railways operating on the South Main Line.

Manila Limited

The Manila Limited was a train service between Manila and Iriga. One train leaves from these two termini each. Train 517 left Manila by 3 pm and arrive in Iriga by 4:15 am. Train 518 will leave Iriga by 2:50 pm and arrive in Manila by 2:35 am. It ended in 2006 when all regular intercity services were terminated.[60]

Prestige Express

The Prestige Express, also nicknamed the VIP Train from some rail enthusiasts of the time, was a limited express service from 1974 to 1981. It ran the full length of the South Main Line, but only stopped at only five stations in-between. In Manila, it only stopped at the historic Paco station. Afterwards, it stops at Lucena in Quezon, Naga in Camarines Sur, and in Daraga and Ligao in Albay. Like all services on the South Main Line, there were added. It service was replaced by the shorter Peñafrancia Express in 1981 that ended at Naga.[61]

It used two classes of Japanese-built diesel multiple units namely, the cowl unit-type multiple unit (later numbered IC-888) and the streamlined "General Manager's Train" or "Nikkō" train set.[62] The latter train sets were named after the service of the same name and its body design was inspired by the 157 series while the nose's design was inspired by the 0 Series Shinkansen EMUs. Both DMUs were acquired in 1974 with the opening of the service.[61] PNR later refurbished the IC-888 trainset in order to serve the Bicol Express in 1998 until 2004.[52] This train was still stored in the Caloocan rail yard without any plans for scrapping as late as 2011.[63]

Peñafrancia Express

The PNR inaugurated the Peñafrancia Express between Manila and Naga City in 1981. It became PNR's premium intercity service and also had airline-style features such as pre-recorded background music, snacks, caterers, and stewardesses. Unlike the preceding Prestige Express, it did not have specialized rolling stock. It was primarily a choice between the acquired refurbished Nikko train acquired from the previous Prestige service, and later the 900 class locomotive and hauled ICF baggage cars and sleeper coaches built in Madras (now Chennai), India.[61]

Initially they were non-stop between Paco Station in Manila and Naga City, save for when the Peñafrancia Express trains headed in opposite directions had to cross each other along the route in Quezon province. Later on, additional stops were added, mostly in the Bicol province of Camarines Sur with the train stopping in towns like Ragay, Sipocot, and Libmanan. This service ended by the late 1990s.[64]

Non-passenger services

The PNR used to offer freight services, using General Electric U15C 900-series locomotives bought by the company in 1974. It is currently planned for a revival leading to the Manila North Harbor.[21]

There was also a limited mobile hospital service. The PNR also operated the PNR Motor Services, a bus service that led to towns that were not serviced by trains. The bus service ended by 1988.

Stations

The Philippine National Railways operates two different rail lines, namely the North Main Line (recently revived) and the South Main Line. Formerly, there were three spur lines, which served various parts of Luzon with its 138 (once) active stations.

Station layout

All PNR stations were and are presently at-grade, with most stations using a side platform layout. Most have only basic amenities, platforms and ticket booths. Rehabilitated stations along the Metro Manila line have been fitted with ramps for passengers using wheelchairs. Several stations have extended platforms, having an upper platform catering to DMU services, and a lower platform for regular locomotive-hauled services.

As of August 2017, most of the stations are being extended and equipped with platform-length roofing, better ticketing office, and restrooms.

Future railway systems under the PNR, such as that of the new North–South Commuter Railway line, proposes elevated stations and platforms similar to the Manila LRT and MRT lines in select sections.

Modernization and expansion plans

The PNR system has suffered from decades of neglect and therefore, several plans to restore and expand the network has been proposed by various administrations. The Republic of Korea, the People's Republic of China, Japan and Indonesia have contributed to these plans. Most of these concern the revitalization and modernization projects of the mainlines in Luzon.[9] As of 2019, the Duterte administration plans a complete overhaul of the PNR system, which involves electrification and conversion from narrow gauge to standard gauge, as well as from single to double track.[65] The standard gauge system is estimated to have a total track length of around 4,000 km (2,500 mi).[66][67]

North–South Commuter Railway

The North–South Commuter Railway (NSCR), or the Clark-Calamba Railway, is the latest project to revitalize both the historic North and South Main Lines. First proposed as "NorthRail", a rapid transit system to connect Metro Manila to Clark International Airport that was to be co-funded by Spain, it had been subject to various cancellations related to funding.[12][68][69][70] It finally came into shape in November 2017 after a resolution of a five-year dispute between the government and a Chinese contractor.[12] The system now includes an expansion of the line to Laguna.

The NSCR will be a 36 station, 147 km (91 mi) elevated railway system from New Clark City in Capas, Tarlac to Calamba, Laguna. It will be the first electrified main line in the country.[71][72] Construction on the Tutuban-Malolos segment or PNR North 1 commenced on February 15, 2019.[73] Once fully completed by 2025, it will accommodate at least 300,000 passengers between Northern Metro Manila and Bulacan alone. While the elevated line will be served by electrified trains, the existing lines below will be used for freight trains and/or existing commuter trains.[74]

Rapid transit involvement

As part of the infrastructure program by president Rodrigo Duterte, East-West Rail was proposed by the East-West Rail Transit Corp., a consortium between Megawide, A. Brown Company Inc., and Private Equity Investment and Development Corp. It involves the financing, design, construction, and maintenance of a mostly-elevated rapid transit line from Diliman in Quezon City to Quiapo in Manila.[75] In 2018, the PNR has said that it will help in building and operating the line. The line will have 11 stations on 9.4 kilometers (5.8 mi) of mostly elevated track. The project is currently awaiting approval from NEDA to proceed. It is also currently tackling right-of-way issues, such as that of the España Boulevard alignment.[76]

South Main Line reconstruction

On October 23, 2019, the Department of Transportation (DoTr) has announced that PNR and the Chinese government has agreed to restore and modernize the South Main Line between Calamba and Legazpi, Albay and eventually to Matnog, Sorsogon. Its gauge will also be widened from narrow gauge to standard gauge with new diesel multiple units from Chinese manufacturer CRRC Zhuzhou Locomotive. The line will initially operate as single-track before eventually upgrading to double track in the long run.[56][57]

For the meantime, PNR is currently testing a new Manila-Naga service using the newly refurbished KiHa 59 trainset before the new South Main Line commences operations in 2021.[77]

Calamba–Batangas City railway restoration

The Calamba–Batangas City branch of the South Main Line will also be restored. The National Economic and Development Authority approved the projects in September 2017 but no clear timeline of construction has been set. In a similar fashion to the South Main Line between Manila and the Bicol Region, it will be initially be opened as a single-track standard gauge line.[78] It will be upgraded to double-track and electrification as part of the planned NSCR South Phase 2 proposed in 2014.[79]

Mindanao Railway

President Rodrigo Duterte expressed his support for the establishment of a railway system in the entire island of Mindanao which could be in operation after his term ends. The railway system to be built in Mindanao will have about 2,000 kilometers of track, and considered one of Rodrigo Duterte's primary infrastructure projects. The first phase, which is 105 kilometers (65 mi), would start construction in the third quarter of 2018 and was expected to be completed by 2022.[80]

High-speed rail

It was initially rumored before the announcement of the North–South Commuter Railway that a "high-speed train line" will connect Metro Manila and Clark International Airport.[81] However, when the new line was announced, the actual maximum speed is only between 120 kilometers per hour (75 mph) for the commuter trains and 160 kilometers per hour (99 mph) for airport express trains and therefore does not qualify for true high-speed rail. Another speculation in form of a map for possible high-speed rail services around the country was spread throughout social media. Department of Transportation Undersecretary Timothy Batan falsified the claims but said that there are plans to build an HSR line and the current rail infrastructure being built are linked for future HSR development.[82]

Freight revival

In 2016, PNR has been interested in reviving its freight services with a planned signing of a memorandum of agreement between the railway and rail freight operator MRAIL (a Meralco subsidiary firm) for the rehabilitation of the rail lines to North Harbor and to restart the freight services starting 2017, which will also help reduce traffic congestion and truck use in the NCR.[83] If completed, MRail will jointly operate the freight service with the PNR, which will end a long absence of railway freight services in the country. This will be the second time the PNR will partner with ICTSI.[84]

A statement made by MRail Inc., a subsidiary of Metro Pacific Investments Corp., said that discussions regarding PNR freight service revival from Port of Manila to the Laguna Gateway Inland Container Terminal resulted in the appointment of a new board at the Philippine National Railways.[85] Representatives of PNR and ICTSI conducted an inspection of the ROW where the former railtracks leading to the North Harbor existed, signalling the start of the action to realize the cargo rail revival.[21]

As of 2019, the freight revival plans are not in effect.

Rolling stock

PNR has operated several types of locomotives, carriages and multiple units as part of its fleet. As of 2019, the rolling stock used are primarily powered by diesel. The DOST Hybrid Electric Train may also function as a battery electric multiple unit although it is started by a diesel engine. All present rolling stock are in 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in). PNR also has rail mounted cranes as supporting equipment with varying capacities from 0.5 to 30 metric tons.

In late 2019, all trains in service except the 203 series-derived coaches underwent refurbishment and livery changes. The multiple units were given an orange and white color scheme and its windows were changed from having steel grills to polycarbonate windows that can resist stoning from illegal settlers while the locomotives have been painted orange.[86]

Locomotives

During the first years of its operation as the Manila-Dagupan Railway, it operated tank engines mostly built in Scotland. The first tender engines appeared in 1907, when the company purchased eight 4-6-0 D class locomotives from the Scottish-English builder Kerr, Stuart and Company. After the Insular Government took over the company by 1917, the company became the Manila Railroad Company and a number of its previous tank engines were converted to tender locomotives as well. By 1919, the American manufacturer H.K. Porter built 20 more D class locomotives. The Porter locomotives will eventually replace the old Scottish locomotives by 1927.[87] Afterwards, larger steam locomotives were purchased in 1929 and then by 1944. The last steam locomotive in service with the American-owned Manila Railroad Company was the Japanese-built 300 class, based on the JNR Class D51. All steam locomotives were considered obsolete by 1956 after the dieselization of MRR began. This is despite some seeing service as late as 1963 and a number of Porter locomotives were later used in movies as late as 1989. Two British-built are preserved in Manila and Dagupan as of 2020, and others were left rotting in rail yards.[88]

By 1956, MRR ordered 20 GE UM12C and 10 ([GE U12C)] streamlined diesel locomotives intended to replace the pre-war Porter D class and US Army locomotives built during World War II.[89] These were replaced by a large order of GE Universal Series locomotives in the 1960s and the 1970s and 10 of 75 units are still in service as of 2019, with 6 more units under refurbishment.[88] In 2020, the PNR received three CC300 series diesel-hydraulic locomotives, which is the first locomotive order since 1973 and first reception since the last 900 class entered regular service in 1991.[90] In addition, the PNR received two sets of switchers for depot work in Tutuban from Italian manufacturer SVI, the first European locomotives to serve the PNR system since the 1980s.

| Class | Image | Manufacturer | Year Built | Units Built | Type | Max Speed | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-4-0 | Hunslet Engine Company | 1885 | 2 | Steam tank engine | Decommissioned[91] | ||

| 2-6-2T (1913) | Kitson-Meyer | 1913 | 4 | Steam tank | Decommissioned[92] | ||

| A (0-6-2) | Neilson and Company | 1886–88 | 14 | Steam tank | Decommissioned[93] | ||

| Murillo Type B (2-4-2) |

|

Dübs and Company | 1886–88 | 5 | Steam tank | Decommissioned, Unit 17 Urdaneta preserved in Dagupan[88] | |

| NBL Type B (0-6-2) |

North British Locomotive Company | 1906–10 | 25 | Steam tank | Decommissioned[87] | ||

| D (4-6-0) | Kerr, Stuart and Company H.K. Porter, Inc. |

1907, 1919–21 | 27 | Steam | Decommissioned[92] | ||

| E (4-6-2T) | North British Locomotive | 1909–14 | 8 | Steam tank | Decommissioned[92] | ||

| H (4-6-0) | American Locomotive Company (Rogers plant) |

1912 | 5 | Steam | Decommissioned[92] | ||

| R (0-8-0) | Maschinenfabrik Esslingen Swiss Locomotive and Machine Works |

1914 | 6 | Steam tank | Decommissioned[92] | ||

| V (0-6-0) |  |

Kerr, Stuart and Company | 1905 | 2 | Steam tank | Decommissioned 1963, Unit 778 (Cabanatuan, renumbered 188) preserved in Tutuban station[88] | |

| W (0-6-2) | Kerr Stuart | 1907 | 4 | Steam tank | Decommissioned in 1927[94] | ||

| X (0-6-2) | Kerr Stuart | 1907 | 8 | Steam tank engine | Decommissioned[92] | ||

| Y (0-4-4) | Hunslet | 1886–88 | 3 | Steam tank engine (tenders were added in later service) | Decommissioned in 1927[95] | ||

| 100 (4-8-2) | Vulcan Iron Works | 1948 | 7 | Steam | 85 km/h (53 mph) | Decommissioned[96][97] | |

| 140 (4-6-2) | Baldwin Locomotive Works | 1926–29 | 10 | Steam | 85 km/h (53 mph) | Decommissioned[98][99] | |

| 200 (2-10-2) | American Locomotive Company | 1922 | 10 | Steam | 85 km/h (53 mph) | Decommissioned[100] | |

| 300 (2-8-2) | Nippon Sharyo | 1951 | 10 | Steam | 85 km/h (53 mph) | Decommissioned[92] | |

| 800 (2-8-2) | Vulcan Iron Works | 1944–45 | 45 | Steam | 100 km/h (62 mph) | Decommissioned by 1956.[101][102] | |

| 900 |  |

GE Transportation | 1973–91 | 21 | Diesel-electric | 103 km/h (64 mph) | In service[88] |

| 1000 | GE Transportation | 1956 | 10 | Diesel-electric | 100 km/h (62 mph) | Decommissioned[103] | |

| 1500 (1,200 hp BBB locomotive) | Alsthom | 1966–1967 | 10 | Diesel-electric boxcab (Converted from electric) |

90 km/h (56 mph) | Decommissioned in 1987[104][105] | |

| 2000 | GE Transportation | 1956 | 20 | Diesel-electric Road switcher |

60 km/h (37 mph) | Decommissioned in 1997[89][106][107][102] | |

| 2500 | _train_(Anonas_Street%252C_Santa_Mesa%252C_Manila)(2017-07-12)_2.jpg.webp) |

GE Transportation | 1965–79 | 43 | Diesel-electric switcher | 103 km/h (64 mph) | 2 units in service[88][89] |

| 3000 (50-ton) | GE Transportation | 1955 | 10 | Diesel switcher | 51 km/h (32 mph) | Decommissioned | |

| 3000 (U6B) | GE Transportation | 1960 | 10 | Diesel-electric | 103 km/h (64 mph) | Rebuilt and renumbered as "5000 Class" in 1992[89] | |

| 3500 | Nippon Sharyo | 1963 | 4 | Diesel-hydraulic | #3501 and #3052 were transfered to Panay Railways in 1960s, and the other were decommisioned in 1979[108] | ||

| 5000 | GE Transportation | 1992 (rebuilt from 3000 Class) | 10 | Diesel-electric | 103 km/h (64 mph) | Not in active service since 2017[88][89][109][110] | |

| 8500 | GE Transportation | 1944 | 2 | Diesel-electric | Decommissioned[111] | ||

| CC203 | PT INKA GE Lokindo |

1998 | 1 | Diesel-electric | 120 km/h (75 mph) | Operated with ICTSI Decommissioned, exported to Australia[89] | |

| CC300 (9000 class) |  |

PT INKA | 2020 | 3 | Diesel-hydraulic | 120 km/h (75 mph) | In service[90] |

Coaches

PNR trains were traditionally consisted of locomotive-hauled coaches with some being refurbished from commuter rail to intercity use to accommodate the Bicol Express. However, since the early 2010s, the government has put several diesel multiple units into service which were either second-hand Japanese trainsets or the Hyundai Rotem EMU that was new at the time. Currently, there are two locomotive-hauled railcar types in service, one of those are the 203 series-derived coaches which were EMUs stripped of motive power components which they have used during their Japanese service. In addition to this, a batch of 15 coaches arrived from Indonesia in 2020.[90]

| Class | Image | Manufacturer | Year Built | Units Built | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7A-100 | Nippon Sharyo, Kinki Sharyo, Teikoku Sharyo, Mecano | 1949–1978 | — | Decommissioned before 1999.[112] | |

| CMC 200 | Tokyu Car | 1976 | 2 | Ex DMU, decommissioned, CMC 201 is Used as a Rerailment Crew Coach.[113] | |

| CMC 300 CTC 100 |

Tokyu Car Kinki Sharyo Fuji Heavy Industries |

1974 - 1980 | About 60 | Ex DMU, decommissioned until late 2000s. CMC 366 and CMC 382 are used as domitory.[114] | |

| 7A-2000 (12 series passenger coach, ex-Japanese National Railways) |

|

Niigata Engineering Fuji Heavy Industries Nippon Sharyo |

1969–1978 (acquired 1999, 2001) |

30 | Decommissioned |

| 7A-2000 (14 series passenger coach, ex-Japanese National Railways) |

Niigata Engineering Fuji Heavy Industries |

1972, 1974 (acquired 1999) |

5 | Decommissioned | |

| NR-00 (12 series ja) |

|

Niigata Engineering Fuji Heavy Industries Nippon Sharyo |

1969–1978 (acquired 2002) |

10 | Decommissioned, 2 coaches are refurbished, and turned into eye clinics |

| 14 series sleeper |  |

Kawasaki Heavy Industries Fuji Heavy Industries Others |

1966–1979 (acquired 2011) | 10 | On storage[115] |

| 203 series-derived coaches |  |

Kawasaki Heavy Industries Nippon Sharyo |

1982 (acquired 2011) | 80 | 30 Units Delivered.[115] 15 units in active service. |

| INKA coaches (8300 class) |  |

PT INKA | 2020 | 15 | In service[90] |

Multiple units

The first multiple units in service with the PNR in 1948 were locally constructed diesel multiple units fitted with Cummins engines, the first ones built by Filipinos.[116] In 1955, the agency ordered another 20 diesel railcars from Japan. It was later complemented and replaced by the box-shaped CMC units built in 1973. The CMC units were used on the Mayon Limited and also became the first trains on the Peñafrancia Express service. The inter-city CMCs were replaced by new streamlined Peñafrancia Express trains in the 1980s while it continued to serve on the PNR Metro Commuter Line until 1999 when it was replaced by Japanese push-pull 7A class coaches.

Since 2009, PNR has acquired several multiple units that were either given second-hand from Japan, or brand new from other countries. This began with the purchase of then brand-new Hyundai Rotem DMUs.[117] This order was followed by several orders of mostly second-hand rolling stock from Japan. In 2018, PNR signed a deal with Indonesian rolling stock manufacturer Industri Kereta Api (PT INKA) for purchase of another six sets of multiple units. By entering service in 2019, these were officially named the 8000 Class.[90] The Department of Science and Technology also helped in building additional stock through the Hybrid Electric Train (HET). This is the first trainset to be designed by Filipino engineers and the first locally-built multiple units since the 1948 Cummins railmotors.[118] It was officially turned over to PNR on June 20, 2019.[119] The government is currently negotiating with local companies for the HET's mass production.

In 2019, with the realization of the North–South Commuter Railway project that has been on hold, PNR ordered thirteen Sustina Commuter electric trains from Japan Transport Engineering Company (J-TREC) and shall begin operations by 2021.[120] The project will be the first part of the system-wide modernization of PNR from narrow gauge and diesel power to standard gauge and electric power that shall happen in the long term.

| Class | Image | Type | Gauge | Manufacturer | Year Built | Top Speed | Units Built | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cummins Railmotor | DMU | 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in) | MRR | 1948 | Decommissioned[116] | |||

| JMC 300 JTC 100 |

Diesel railcar | 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in) | Tokyu Car Daichi Bussan (Contract by) |

1955 | 95 km/h (59 mph) | 100 (5 units per train) | Decommissioned in 1985[121][122] | |

| KiHa 52–100 |  |

DMU | 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in) | Niigata Engineering | 1962–66 (acquired 2011) | 80 km/h (50 mph) | 7 (1/3 cars per set) | In service, ex-East Japan Railway Company, originally built for Japanese National Railways |

| KiHa 350 |  |

DMU | 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in) | Teikoku Car Fuji Heavy Industries Nippon Sharyo |

1961–66 (acquired 2011) | 80 km/h (50 mph) | 6 (2 cars per set) | In service, ex-Kanto Railway, originally built for Japanese National Railways |

| KiHa 59 |  |

DMU | 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in) | Niigata Engineering Fuji Heavy Industries Rebuilt by East Japan Railway Company |

1967–68 1989 (as KiHa 59) (acquired 2011) |

80 km/h (50 mph) | 3 (3 cars per set) | In service,[90] ex-East Japan Railway Company, originally built for Japanese National Railways |

| MC 300 CT 1 |

DMU | 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in) | Tokyu Car | 1967-68 | Decommissioned[123][124] | |||

| Mayon Limited DMU (MCBP&TAs) |

DMU | 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in) | Tokyu Car | 1973 | 95 km/h (59 mph) | 16 (8 cars per set) | Decommissioned[125] | |

| CMC 200 | DMU | 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in) | Tokyu Car | 1976 | 95 km/h (59 mph) | 2 | Decommissioned as DMU, only CMC 201 is used as Rerailment crew loco-hauled coach.[113] | |

| CMC 300 CTC 100 |

DMU | 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in) | Tokyu Car Kinki Sharyo Fuji Heavy Industries |

1974–80 | 95 km/h (59 mph) | 60 (3 Cars per set) | Decommissioned as DMU in 1999, after then, these DMUs were rebuilt as passenger coaches, operated by late 2000s[126][114] | |

| Nikkō | DMU | 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in) | Tokyu Car | 1974 1998 (Refurbished as IC-888) |

100 km/h (62 mph) | 26 (2–3 per train) | Former JMC Railcar, 7 units refurbished in 1998 as Bicol Express T-577.[52] Decommissioned in 2004.[127] | |

| Hyundai Rotem DMU |  |

DMU | 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in) | Hyundai Rotem | 2009–10 | 80 km/h (50 mph) | 18 (3 cars per set) | In service[117] |

| DOST HET (Hybrid-electric train prototype) |  |

Hybrid DMU/BEMU | 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in) | DOST–MIRDC Fil-Asia Automotive |

2019–20 | 80 km/h (50 mph) | 5 (5 cars per set) | Prototype unit in service, more units in order[128][129] |

| 8000 8100 |

|

DMU | 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in) | PT INKA | 2019–20 | 100 km/h (62 mph) | 22 (3/4 cars per set) | In service[90] |

| Sustina/E233-type NSCR EMUs | EMU | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) | J-TREC | 2021 | 120 km/h (75 mph) | 104 (8 cars per set) | On order[120] | |

| CRRC Intercity DMUs | DMU | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) | CRRC Zhuzhou Locomotive | 2021 | 160 km/h (99 mph)[130] | 9 (3 cars per set) | On order[57] | |

Liveries

The Manila-Dagupan Railway, the Manila Railroad Company and the Philippine National Railways sported various liveries representing various eras of the company, usually to celebrate the arrival of new rolling stock. Each of these are painted by hand.[131]

Steam locomotive era (1892–1954)

There were no available colored images of Manila-Dagupan Railway and the Manila Railroad Company's rolling stock before the war so the color scheme of the carriages remains unknown. However, based on the surviving locomotives, the steam locomotives owned by the two companies sported a black-only livery like most of the notable American steam engines.[88]

Railmotor livery (1948)

The Cummins railmotors were colored black or white, and orange. The pre-war carriages salvaged and refurbished in the late 1940s also used this color scheme.[132]

MRR/PNR livery (1955)

The MRR celebrated the arrival of its first diesel rolling stock with its colors changed to dark green and yellow, or alternately to yellow-orange and dark green. The livery was retained when the Philippine government took over and renamed it the Philippine National Railways. During the transition to PNR, the old MRR monogram with a diamond-shaped seal was painted out and the PNR circular seal and monogram was placed on the front of the cab with yellow wing-like symbols outside it. The PNR acronym is also placed on the sides as well.[133] By the 1980s, the diesel multiple units will have a yellow body and the wing-like symbols are colored dark green. A few locomotives sported a yellow-orange livery at that time.

Commuter Motor Coach livery (c. 1978)

During the late 1970s, the Commuter Motor Coaches used on PNR's local train services in Metro Manila and the Bicol Region was colored white and navy blue.[134]

Metrotren livery (1990)

When President Corazon Aquino inaugurated the rebranded Manila commuter service as "Metrotren" in 1990, the CMC coaches were repainted to navy blue, white and red. This was also used for the 1998 restocking of the Bicol Express with the old Peñafrancia Express IC-888 train. This was used until the mid 2000s when both multiple unit types were changed to the navy blue livery.[135]

Philippines 2000 livery (1997)

The GE Universal Series-based 900, 2500 and 5000 classes sported a red livery celebrating Fidel Ramos' Philippines 2000 program.[136] Although the PNR revised this livery after 2000, some retained it due to lack of maintenance funds and a 900 class survived with this livery in use until 2008. Some of the freight carriages had the Philippines 2000 name spray-painted on top the old green and yellow livery.[137]

Navy blue livery (c. 2000, 2011)

A navy blue livery was introduced after the expiry of the Philippines 2000 program. This followed after PNR acquired locomotive-hauled 12 and 14 series coaches from Japan. There are subtle differences with the coaches used on the Commuter Express (formerly Metrotren) and the Bicol Express. The Commuter Express trainsets were navy blue with orange highlights while the Bicol Express were navy blue with gold highlights. The PNR symbol on the Commuter Express was white while on the Bicol Express was gold. The locomotives' colors were also changed to navy blue and orange.

This livery was re-introduced in 2011 although it was not used on the Bicol Express trainsets.

Filtrack livery (2009)

PNR attempted to revitalize the Bicol Express in 2009 with the support of president Gloria Macapagal Arroyo. This was supported with a change of logo and liveries. The coaches in PNR service used white and orange while the locomotives' cabs were colored white while the PNR monogram logo was sealed out. The trains also sported the "Filtrack" brand on the coaches and on the side of the locomotives. However, this was short lived after the Bicol Express stopped its services indefinitely. By 2015, all of the rolling stock followed the 2000s navy blue livery.

INKA livery (2019)

.

The PNR announced another logo change and changes to its livery in 2019. This is after the Duterte administration under the Department of Transportation announced major reforms to the PNR. The PNR's monogram is now fully incorporated on a seal-type logo, bearing the agency's name and the year it was founded. The seal was also changed from orange and blue to golden yellow and navy blue. At the same time, the rolling stock also changed its liveries with regards to the arrival of the new rolling stock from Indonesia. The 203 series-based passenger cars' liveries did not change as of 2020.

The first among the old rolling stock was the KiHa 350 and KiHa 59 series trains. After this was the Hyundai Rotem DMUs and finally, 900 series locomotive DEL 917, 5000 series locomotive DEL 5007 and 2500 series locomotive DEL 2540 changed its livery to orange, similar to the upcoming CC300s. All multiple units were fitted with new windows to resist stoning. The colors however varied from one type of rolling stock to another but the common theme was the inclusion of orange (as the highlight color), white (as the main stock color), navy blue (as the side line color) and black (as the bottom color).

CRRC diesel multiple unit livery (2021)

The latest effort to the revitalization of the South Main Line, particularly the Bicol Express intercity service, was unveiled in 2019 dubbed the "South Long Haul" project. A scale model of the train that will be used was revealed during a contract signing ceremony between the Philippine National Railways, its superior agency the Department of Transportation, and the Chinese rolling stock manufacturer CRRC Zhuzhou Locomotive. The three-car train will also feature a red-orange livery with black stripes on its windows. This train is set to arrive by 2021.

See also

- Department of Transportation

- List of Philippine National Railways stations

- Panay Railways

- Rail transportation in the Philippines

- Strong Republic Transit System

Notes

- ^ Inter-city and freight services have been suspended since 2016. The North–South Commuter Railway will be the first intercity service since the discontinuation of the Bicol Express in 2016. Construction of the line commenced in 2019. There are also plans to revitalize to freight service. See Freight revival for more information.

References

- "Fares & Tickets". Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- "Sad saga of PNR". Philippine Daily Inquirer. May 13, 2014. Retrieved July 29, 2014.

- "Bicol Express revival hinges on safety issues". The Philippine Star. December 29, 2013. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- "Train: Naga to Legazpi open! Soon again Bicol Express?". September 9, 2015. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- "Brief history of PNR". Philippine National Railways (February 27, 2009). Archived from the original on February 27, 2009. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- "Manila Railroad Company". National Register of Historic Sites & Structures in the Philippines. National Historical Commission of the Philippines. Retrieved September 6, 2013.

- "Chapter I: Present Conditions". Report of Survey of the Manila Railroad Company and the Preliminary Survey of Railroads for Mindanao (Report). Chicago: De Leuw, Cather & Company. 1951. pp. 1–12.

- "Off track: Northrail timeline". ABS-CBN News. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

- Maragay, Fel V. (December 15, 2005). "Rehab of busy railway". Manila Standard Today. Archived from the original on July 21, 2006. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- Olchondra, Riza T. (April 22, 2007). "PNR rail rehabilitation to start September". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Manila. Archived from the original on February 21, 2013. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

The Philippine National Railways (PNR) will start repairing and improving its North and South railways by September, PNR General Manager Jose Ma. Sarasola II said Friday.

- Escandor Jr., Juan; Caudilla, Pons (September 18, 2009). "Bicol train chugs to a halt in test run". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Manila. Archived from the original on September 22, 2009. Retrieved April 29, 2010.

The spirit was willing, but the diesel-fed old engines were not.

- "Off track: Northrail timeline". ABS-CBN News. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

- "RP, China break ground for Manila-Ilocos railway". Malaya. April 6, 2004. Archived from the original on May 9, 2010.

- "U.P. study finds North Rail contract illegal, disadvantageous to government". The PCIJ Blog. September 9, 2005. Archived from the original on August 12, 2014. Retrieved July 29, 2014.

- <http://www.abs-cbnnews.com/business/07/22/13/dotc-eyes-elevated-railway-malolos-los-banos

- "Govt eyes elevated rail project in Luzon". Archived from the original on January 2, 2014. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- "17 stations of Manila-Clark Railway announced". Rappler. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- "20 YEARS AFTER: DOTr sees 10,000 passengers taking PNR's reopened Caloocan-Dela Rosa line". GMA News. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- "After 20 years, PNR's Caloocan to Makati line to reopen". ABS-CBN News. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- "Department of Transportation – Philippines". www.facebook.com. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- "Department of Transportation – Philippines". Facebook.com.

- Yee, Jovic. "PNR to offer freight service soon". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- "Philippine National Railways".

- "Philippine National Railways".

- "Department of Transportation – Philippines".

- "DMCI, Japanese partner bag P54-B contract for North-South Commuter Railway project". GMA News.

- Locus, Sundy (October 1, 2019). "PNR chugs way to global standards".

- "Department of Transportation – Philippines".

- "Department of Transportation – Philippines".

- "Philippine National Railways".

- "Completed railway assets to ease traffic by 25%: DOTr". Philippine News Agency.

- "Metro Commuter". Philippine National Railways. Archived from the original on March 17, 2011. Retrieved June 8, 2014.

- "Time Table".

- "DOST-Science and Technology Information Institute". Facebook. Archived from the original on June 3, 2019.

- "Philippine National Railways".

- "Department of Transportation – Philippines".

- "Department of Transportation – Philippines".

- "Department of Transportation – Philippines". www.facebook.com.

- "Daily Operations Report – July 15, 2020". Philippine National Railways Official Facebook Page. July 15, 2020. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- "PNR Inaugural Bicol Express Train passing through the eroded embankment at Sipocot". YouTube. July 2, 2011. Retrieved March 1, 2020.

- "PNR 917 passing Gumaca, Quezon". YouTube. July 2, 2011. Retrieved March 1, 2020.

- "Manila North Line". When There Were Stations: Asia. Retrieved March 8, 2020.

- "Meycauayan". When There Were Stations: Asia. Retrieved March 8, 2020.

- "1974 0215 PNR Amianan Expre.ss Trains". Flickr. March 20, 2011. Retrieved March 8, 2020.

- "1955 0916 MRR Package Tour ad". Flickr. September 16, 2010. Retrieved March 11, 2020.

- "1984 PNR MOTOR SERVICES". Flickr. June 22, 1984. Retrieved March 11, 2020.

- "1974 0215 PNR Amianan Express Trains". Flickr. January 12, 2012. Retrieved March 8, 2020.

- "Official Week in Review: April 12 – April 18, 1959". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Retrieved March 11, 2020.

- "MRR at Lucena from The Philippine Herald dated September 7, 1961". Flickr. September 7, 1961. Retrieved March 11, 2020.

- "1942 0619 Affairs Concerning Railway Battalion of the Imperial Japanese Forces". Flickr. January 8, 2014. Retrieved March 11, 2020.

- "1954 0814 New MRR Train Time Schedule". Manila Chronicle. August 14, 1954. Retrieved March 11, 2020 – via Flickr.

- 1998 0623 General Manager's Train T-577 – Flickr.

- "Trains & Schedules". Official Website. Philippine National Railways. Archived from the original on August 20, 2013. Retrieved September 6, 2013.

Manila – Bicol trips are currently suspended. Please bear with us.

- "PNR to resume Bicol Express in Sept". GMA News. May 9, 2014. Retrieved July 29, 2014.

- "Bicol Express operations cancelled". Manila Bulletin. November 19, 2016. Retrieved January 4, 2017.

- "Department of Transportation – Philippines". Facebook.com.

- "Chinese firm signs contract to supply trains for PNR Bicol project". ABS-CBN News. Retrieved December 23, 2019.

- "Mayon Limited resumes Bicol run". Philippine National Railways Press Release. Manila. Archived from the original on March 24, 2012. Retrieved March 19, 2012.

- "Mayon Limited". Archived from the original on March 17, 2012. Retrieved March 19, 2012.

- "1991 0108 Train Schedules". Flickr. December 17, 2012. Retrieved March 11, 2020.

- "PNR Nikko Express". Express Travel Blog (in Japanese). Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- "PNR VIP Train". Philippine Trains Wikia. Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- "PNR IC-888". Flickr. Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- "1974 0409 PNR Integrated Transport System ad". Flickr. Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- "Philippines approves standard gauge for all new lines". www.railwaypro.com. August 10, 2016. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- "Bidding Documents — Advanced Preliminary Works of the Subic–Clark Railway" (PDF). Bases Conversion and Development Authority. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- "The Mindanao Railway consists of 1,532 kilometers of circumferential and spur lines." from "Department of Transportation Presentation" (PDF). Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- "WHAT WENT BEFORE: The Northrail Project". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved February 16, 2019.

- "Philippines: China-funded Northrail project derailed". Financial Times. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

- "U.P. study finds North Rail contract illegal, disadvantageous to government". The PCIJ Blog. September 9, 2005. Retrieved July 29, 2014.

- Main Points of the Roadmap (PDF) (Report). Japan International Cooperation Agency. September 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 11, 2014.

- "PRE-BID CONFERENCE FOR CONTRACT PACKAGES CP01 and CP02 North-South Commuter Railway" (PDF). philgeps.gov.ph. June 1, 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 20, 2018. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- "Construction of Tutuban-Malolos railway begins". Manila Bulletin. Retrieved February 18, 2019.

- Camus, Miguel R. "DOTr plans to integrate new railway lines". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved February 16, 2019.

- PNR East-West Railway Project Details Public Private Partnership Center. Retrieved January 18, 2018.

- Megawide's proposed East-West Railway to cost $1 billion Rappler. Retrieved January 18, 2018.

- Garcia, Leandre. "PNR". TopGear Philippines. Retrieved February 16, 2019.

- Dela Paz, Chrisee (September 13, 2017). "NEDA Board approves Metro Manila Subway". Rappler. Rappler. Retrieved September 14, 2017.

- "Roadmap for Transport Infrastructure Development for Metro Manila and its Surrounding Areas (Region III and Region IV-A)" (PDF). Japan International Cooperation Agency. March 30, 2014. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- "Build Build Build Presentation" (PDF). Build Build Build. May 20, 2017. Retrieved July 14, 2017.

- "OP.gov.ph". OP.gov.ph. May 9, 2013. Retrieved August 24, 2013.

- "Fact Check: No, this is not a map of the Philippines' high-speed rail system". The Philippine Star. Agency France-Presse, through The Philippine Star. October 20, 2018. Retrieved November 23, 2019.

- "PNR gagamitin sa pagde-deliver ng mga kargamento; mabigat na trapiko at port congestion maaaring mabawasan". January 28, 2016.

- "Report: Cargo trains to be revived to reduce truck traffic – Auto News". AutoIndustriya.com. August 8, 2016.

- Camus, Miguel R. "MVP group, ICTSI to push P10-B railway plan". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved July 20, 2017.

- railfan.jp (in Japanese)

- Corpuz, Arturo. The Colonial Iron Horse: Railroads and Regional Development in the Philippines, 1875–1935. University of the Philippines Press.

- Today's Railways and Preserved Steam in the Philippines. International Steam. Retrieved December 18, 2019.

- GE UM12C Roster. The Diesel Shop.

- Cabalza, Dexter. "PNR buys seven more trains worth P2.37-B from Indonesia". Philippine Daily Inquirer.

- "Inside of the train shed at the main Manila RR Station – 1899". Flickr. Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- "Manila Railroad". Locomotive Engineers Journal. 90. 1956.

- "Manila and Dagupan Railway, Neilson & Co., Glasgow, Philippines, 1890". Flickr. Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- Locomotive of the Manila-Dagupan RR ca 1900 – Flickr.

- "Hunslet Manila". Philippine Trains Wikia. Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- "1948 0331 Mountain Type Locomotive. From the Manila Bulletin – March 31, 1948". Flickr. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- "Vulcan 106". Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- "1940 10 MRR train. From The Commerce October 1940". Flickr. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- Baldwin Locomotive Works List.

- "Manila RR 'Santa Fe' Locomotive 2-10-2 – 1922". Flickr. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- "MRR Steam Locomotive (1956)". Flickr. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- "The Old and the New, November 24, 1956". Flickr. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- 1957 Bicol Express train.

- MRR/PNR Alsthom Promotional Poster (1966) – Flickr.

- Locomotives for PNR From the Sunday Chronicle – Nov. 20, 1966

- Phil's Loco Page (July 4, 2015). "GE Export".

- PNR UM12C Image (1961) – Flickr.

- PHILIPPINE NATIONAL RAILWAYS LOCOMOTIVE STATUS - Philippine Railway Historical Society - Retrieved January 25, 2021

- DEL 5009 in 2010

- DEL 5001 in 2016

- "8591 Caloocan". Philippine Trains Wikia. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- "1973 Mayon Express Ltd". July 26, 2010 – via Flickr.

- "PNR 917 passing Gumaca, Quezon". September 21, 2019 – via YouTube.

- Spotlight on CMC CTC Railcars. - Philippine Railway Historical Society

- 日本の中古電車に熱視線 9月に引退した通勤車両、フィリピンで第二の人生 [Commuter trains retired in September to live a second life in the Philippines]. Sankei News (in Japanese). Japan: The Sankei Shimbun & Sankei Digital. November 26, 2011. Archived from the original on April 14, 2012. Retrieved April 16, 2012.

- 1948 0331 New Rail Motor train – Flickr.

- "Railway Systems-Project Record View". www.hyundai-rotem.co.kr. Retrieved December 25, 2018.

- "DOST's Hybrid Electric Train Inauguration". techmagus. April 29, 2019. Retrieved April 29, 2019.

- "DOST-MIRDC turns over the Hybrid Electric Train (HET) to the PNR". The Official Website of Metals Industry Research and Development Center. Retrieved June 26, 2019.

- Charm, Neil. "DoTr prepares to award rolling stock contract". BusinessWorld. Retrieved December 18, 2019.

- 1955 1219 New MRR Diesel Cars

- 1958 0908 MRR New Rail Cars.

- 1968 0120 PNR San Fernando Commuter Train - Flickr.

- 1975 0428 Derailed - Flickr.

- 1973 Mayon Express Limited – Flickr.

- Philippine National Railways (PNR) Diesel Rail Car set lead by CMC 376 and CMC 374 trailing just south of Buendia Railway Station, Manila, Philippines.

- "Philippine National Railways Rolling Stock Status". Philippine Railway Historical Society. Retrieved March 21, 2020.

- Pa-a, Saul (April 24, 2019). "1st Filipino hybrid train runs from Calamba to Manila". Philippine News Agency. Philippine News Agency. Retrieved December 18, 2019.

- Meet the First Filipino-Built Train: The Hybrid Electric Train (HET). Carmudi.com.ph. Retrieved December 18, 2019.

- "FALSE: PNR Bicol Express 'reopened' September 2019". Rappler. Retrieved December 25, 2018.

- "GEDC2105". Flickr. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- "MotorTrain-1". Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- "1978 LOCO No. 901". Flickr. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- "1980 PNR TO CARMONA". Flickr. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- "06649 (228) 04-02-1990 Philippine National Railways (PNR) in the yard outside the workshops I building with a Metrotren carriage in Kaloocan City, Manila, Philippines". Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- "908 Tayuman". Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- "1999 0318 PNR Philippines 2000".

Further reading

- Uranza, Rogelio. (2002). The Role of Traffic Engineering and Management in Metro Manila. Workshop paper presented in the Regional Workshop: Transport Planning, Demand Management and Air Quality, February 2002, Manila, Philippines. Asian Development Bank (ADB).

- World Bank (May 23, 2001). "Project Appraisal Document for the Metro Manila Urban Transport Integration Project" (PDF). World Bank.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Philippine National Railways. |

- Philippine National Railways (official website)

- Official Facebook page of Philippine National Railways

- Facebook page of Philippine Railways

- Twitter page of Philippine Railways

- Facebook for Philippine Railway Historical Society