Rathlin Island

Rathlin Island (from Irish: Reachlainn, IPA:[ˈɾˠaxlən̪ʲ])[2] is an island and civil parish off the coast of County Antrim (of which it is part) in Northern Ireland. It is Northern Ireland's northernmost point.

| Rathlin Island | |

|---|---|

True-color ESA Sentinel-2 image of Rathlin Island | |

Rathlin Island Location within Northern Ireland | |

| Population | 154 |

| Irish grid reference | D134518 |

| • Belfast | 47 mi (76 km) |

| District | |

| County | |

| Country | Northern Ireland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Ballycastle |

| Postcode district | BT54 |

| Dialling code | 028 |

| Police | Northern Ireland |

| Fire | Northern Ireland |

| Ambulance | Northern Ireland |

| UK Parliament | |

| Website | Rathlin Development & Community Association's official website |

Geography

Rathlin is the only inhabited offshore island of Northern Ireland, with a steadily growing population of approximately 150 people, and is the most northerly inhabited island off the coast of the island of Ireland. The reverse L-shaped Rathlin Island is 4 miles (6 kilometres) from east to west, and 2 1⁄2 miles (4 kilometres) from north to south.

The highest point on the island is Slieveard, 134 metres (440 feet) above sea level. Rathlin is 15 1⁄2 miles (25 kilometres) from the Mull of Kintyre, the southern tip of Scotland's Kintyre peninsula. It is part of the Causeway Coast and Glens council area, and is represented by the Rathlin Development & Community Association.[3]

Townland

Rathlin is part of the traditional barony of Cary (around the town of Ballycastle), and of current district Moyle. The island constitutes a civil parish and is subdivided into 22 townlands:

| Townland | Area acres[4] |

Population |

|---|---|---|

| Ballycarry | 298 | ... |

| Ballyconagan | 168 | ... |

| Ballygill Middle | 244 | ... |

| Ballygill North | 149 | ... |

| Ballygill South | 145 | ... |

| Ballynagard | 161 | ... |

| Ballynoe | 80 | ... |

| Carravinally (Corravina Beg) | 116 | ... |

| Carravindoon (Corravindoon) | 188 | ... |

| Church Quarter | 51 | ... |

| Cleggan (Clagan) | 202 | ... |

| Craigmacagan (Craigmacogan) | 153 | ... |

| Demesne | 67 | ... |

| Glebe | 24 | ... |

| Kebble | 269 | ... |

| Kilpatrick | 169 | ... |

| Kinkeel | 131 | ... |

| Kinramer North | 167 | ... |

| Kinramer South (Kinramer) | 173 | ... |

| Knockans | 257 | ... |

| Mullindross (Mullindress) | 46 | ... |

| Roonivoolin | 130 | ... |

| Rathlin | 3388 (1371 ha) | ... |

Irish language

The Irish language was originally spoken on Rathlin Island until around the 1960s and was perhaps the main community language until the early 20th century. As it is located between the Irish and Scottish mainland, the dialect found on Rathlin shared many features of both languages while also being unique in structure and grammar, e.g. forming plurals with -án or -eán (/ɑːnˠ/) doing away with inflection for weak nouns and suffixes for strong ones. [5]

In addition, the phonology of the dialect was quite divergent, compare "íorbáll" /ˈiɾˠbˠɑlˠ/ with Standard Irish "eireaball" /ˈɛɾʲəbˠəlˠ/ and Scottish Gaelic "earball" /ˈɛɾəpəl/.

Transport

A ferry operated by Rathlin Island Ferry Ltd connects the main port of the island, Church Bay, with the mainland at Ballycastle, 6 miles (10 kilometres) away. Two ferries operate on the route – the fast foot-passenger-only catamaran ferry Rathlin Express and a purpose-built larger ferry, commissioned in May 2017, Spirit of Rathlin, which carries both foot passengers and a small number of vehicles, weather permitting.[6][7] Rathlin Island Ferry Ltd won a six-year contract for the service in 2008 providing it as a subsidised "lifeline" service.[8] There is an ongoing investigation on how the transfer was handled between the Environment Minister and the new owners.[9]

Natural history

Rathlin is of prehistoric volcanic origin, having been created as part of the British Tertiary Volcanic Province.[10]

Rathlin is one of 43 Special Areas of Conservation in Northern Ireland. It is home to tens of thousands of seabirds, including common guillemots, kittiwakes, puffins and razorbills – about thirty bird families in total. It is visited by birdwatchers, with a Royal Society for the Protection of Birds nature reserve that has views of Rathlin's bird colony. The RSPB has also successfully managed natural habitat to facilitate the return of the red-billed chough. Northern Ireland's only breeding pair of choughs can be seen during the summer months.

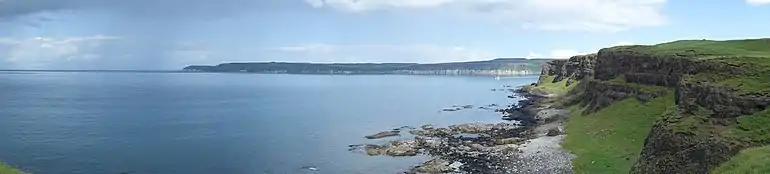

The cliffs on this relatively bare island are impressive, standing 70 metres (230 ft) tall. Bruce's Cave[11] is named after Robert the Bruce, also known as Robert I of Scotland: it was here that he was said to have seen the legendary spider which is described as inspiring Bruce to continue his fight for Scottish independence.[12] The island is also the northernmost point of the Antrim Coast and Glens Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.[13]

In 2008-09, the Maritime and Coastguard Agency of the United Kingdom and the Marine Institute Ireland undertook bathymetric survey work north of Antrim, updating Admiralty charts (Joint Irish Bathymetric Survey Project). In doing so a number of interesting submarine geological features were identified around Rathlin Island, including a submerged crater or lake on a plateau with clear evidence of water courses feeding it. This suggests the events leading to inundation - subsidence of land or rising water levels - were extremely quick.

Marine investigations in the area have also identified new species of sea anemone, rediscovered the fan mussel (the UK's largest and rarest bivalve mollusc - thought to be found only in Plymouth Sound and a few sites off the west of Scotland) and a number of shipwreck sites,[14][15] including HMS Drake,[16] which was torpedoed and sank just off the island in 1917.

History

Rathlin was probably known to the Romans, Pliny referring to "Reginia" and Ptolemy to "Rhicina" or "Eggarikenna". In the 7th century, Adomnán mentions "Rechru" and "Rechrea insula", which may also have been early names for Rathlin.[17] The 11th century Irish version of the Historia Brittonum states that the Fir Bolg "took possession of Man and of other islands besides – Arran, Islay and 'Racha'" – another possible early variant.[18]

Rathlin was the site of the first Viking raid on Ireland, according to the Annals of Ulster. The pillaging of the island's church and burning of its buildings took place in 795.

In 1306, Robert the Bruce sought refuge upon Rathlin, owned by the Irish Bissett family. He stayed in Rathlin Castle, originally belonging to their lordship the Glens of Antrim. The Bissetts were dispossessed of Rathlin by the English, who were in control of the Earldom of Ulster, for welcoming Bruce. In the 16th century, the island came into the possession of the MacDonnells of Antrim.

Rathlin has been the site of a number of massacres. On an expedition in 1557, Sir Henry Sidney devastated the island. In July 1575, the Earl of Essex sent Francis Drake and John Norreys to confront Scottish refugees on the island, and in the ensuing massacre, hundreds of men, women and children of Clan MacDonnell were killed.[19][20] Also in 1642, Covenanter Campbell soldiers of the Argyll's Foot were encouraged by their commanding officer Sir Duncan Campbell of Auchinbreck to kill the local Catholic MacDonalds, near relatives of their arch clan enemy in the Scottish Highlands Clan MacDonald. They threw scores of MacDonald women over cliffs to their deaths on rocks below.[21][22] The number of victims of this massacre has been put as low as 100 and as high as 3,000.

On 2 October 1917, the armoured cruiser HMS Drake was torpedoed off the northern Irish coast by German submarine U-79. She steamed into Church Bay on Rathlin Island, where, after her crew was taken off, she capsized and sank.

Commerce

In 1746, the island was purchased by the Reverend John Gage.[23] In the later 18th century, kelp production became important, with Rathlin becoming a major centre for production. The shoreline is still littered with kilns and storage places. This was a commercial enterprise sponsored by the landlords of the island and involved the whole community.[24]

A 19th-century British visitor to the island found that they had an unusual form of government where they elected a judge who sat on a "throne of turf".[25] In fact, Robert Gage was the "proprieter of the island" until his death in 1891. Gage held a master's degree from Trinity College, Dublin, but he spent his life on the island creating his book "The Birds of Rathlin Island".[26]

Tourism is now a commercial activity. The island had a population of over one thousand in the 19th century. Its current permanent population is around 125. This is swollen by visitors in the summer, with most coming to view the cliffs and their huge seabird populations. Many visitors come for the day, and the island has around 30 beds for overnight visitors. The Boathouse Visitors' Centre at Church Bay is open seven days a week from April to September, with minibus tours and bicycle hire also available. The island is also popular with scuba divers, who come to explore the many wrecked ships in the surrounding waters.

Richard Branson crashed his hot air balloon into the sea off Rathlin Island in 1987 after his record-breaking cross-Atlantic flight from Maine.[27]

On 29 January 2008, the RNLI Portrush lifeboat Katie Hannan grounded after a swell hit its stern on breakwater rocks just outside the harbour on Rathlin while trying to refloat an islander's RIB. The lifeboat was handed over to a salvage company.[28][29]

Communications

The world's first commercial wireless telegraphy link was established by employees of Guglielmo Marconi between East Lighthouse on Rathlin and Kenmara House in Ballycastle on 6 July 1898.[30]

In July 2013, BT installed a high-speed wireless broadband pilot project to a number of premises, the first deployment of its kind anywhere in the UK, 'wireless to the cabinet' (FTTC) to deliver 80Mbs to users.[31]

Archaeology

Tievebulliagh mountain near Cushendall, on the mainland coast nearby, features a Neolithic stone axe factory, and a similar one is to be found in Brockley, a cluster of houses within the townland of Ballygill Middle,[32] featuring the same porcellanite stone. The products of these two axe factories, which cannot be reliably distinguished from each other, were traded across Ireland; these were the most important Irish factories.[33]

The island was also settled during the Mesolithic period. There is an unexcavated Viking vessel in a mound formation.[34]

References

- Chadwick, Hector Munro (1949) Early Scotland: the Picts, the Scots & the Welsh of southern Scotland. Cambridge University Press.

- Watson, W. J. (1994) The Celtic Place-Names of Scotland. Edinburgh; Birlinn. ISBN 1-84158-323-5. First published in Edinburgh; The Royal Celtic Society, 1926.

- Rathlin Island and the Gaelic Language (2005) "Rathlin Island and the Gaelic Language". https://www.culturenorthernireland.org/features/heritage/rathlin-island-and-gaelic-language

Notes

- Beagmore stone circles and alignments and Cregganconroe court grave NI Department of the Environment. Retrieved 2012-10-15.

- "Place Names NI - Home". www.placenamesni.org. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- "The official website of the Rathlin Development & Community Association". Rathlin Community. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- The Ire Atlas TOWNLAND DATABASE, Civil Parish: Rathlin Island

- https://www.culturenorthernireland.org/features/heritage/rathlin-island-and-gaelic-language

- "Rathlin". Rathlinweather.co.uk. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- "Press Release" (PDF). Rathlin Island Ferry Ltd. 28 April 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 2 August 2009.

- "Improved service for Rathlin ferry will half travel time". Northern Ireland Executive. 21 April 2008. Retrieved 2 August 2009.

- "Probe into tendering contract of ferry run". News Letter (Johnston Press). 18 June 2008. Retrieved 2 August 2009.

- "Causeway Coast and Rathlin Island Geodiversity Profile". Northern Ireland Environment Agency. Archived from the original on 7 October 2009. Retrieved 2 August 2009.

- "Bruce's Cave". Bruce Rathlin 700. The Ulster-Scots Agency. Archived from the original on 21 October 2011. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

Verifying Rathlin Island's connections with King Robert the Bruce

- "The Spider Legend". Bruce Rathlin 700. The Ulster-Scots Agency. Archived from the original on 8 January 2014. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

It’s a famous story, but is it true?

- "Antrim Coast and Glens AONB". Northern Ireland Environment Agency. Retrieved 2 August 2009.

- "The Joint Irish Bathymetric Survey Project". MCA. Archived from the original (Video) on 26 March 2009. Retrieved 2 August 2009.

- "Prehistoric land under the sea". BBC News. 30 July 2008. Retrieved 2 August 2009.

- Wilson, Ian (2011) HMS Drake. Rathlin Island Shipwreck. Rathlin Island: Rathlin Island Books. ISBN 978-0-9568942-0-5

- Watson (1994) pp. 6, 37.

- Chadwick (1949) p. 83

- John Sugden, "Sir Francis Drake", Touchstone-book, published Simon+Schuster, New York, ISBN 0-671-75863-2

- "Sir Francis Drake and Music". The Standing Stones. Retrieved 2 August 2009.

- Royle, Trevor (2004), Civil War: The Wars of the Three Kingdoms 1638-1660, London: Abacus, ISBN 0-349-11564-8 p.143

- "The Carolingian Era". MacDonnell Of Leinster Association. Archived from the original on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 28 August 2008.

- Ferriter, Diarmaid (4 October 2018). On the Edge: Ireland's off-shore islands: a modern history. Profile Books. ISBN 9781782832522.

- O'Sullivan, Aidan & Breen, Colin (2007). Maritime Ireland. An Archaeology of Coastal Communities. Stroud: Tempus. p. 225. ISBN 978-0-7524-2509-2.

- The Saturday Magazine. John William Parker. 1834. p. 134. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- "The Dictionary of Ulster Biography". www.newulsterbiography.co.uk.

- Raines, Howell; Times, Special To the New York (4 July 1987). "2 Trans-Atlantic Balloonists Saved After Jump into Sea Off Scotland". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- "£2m lifeboat's rescue called off". BBC News. 30 January 2008. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- "Permanent replacement lifeboat for Portrush". RNLI press release. 18 April 2008. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- "Guglielmo Marconi 1874-1937". northantrim.com. Retrieved 2 August 2009.

- "BT Ireland". btireland.com. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- Weir, A (1980). Early Ireland. A Field Guide. Belfast: Blackstaff Press. p. 96.

- Wallace, Patrick F., O'Floinn, Raghnall eds., Treasures of the National Museum of Ireland: Irish Antiquities, pp. 46-47, 2:4, 2002, Gill & Macmillan, Dublin, ISBN 0717128296

- O'Sullivan, Aidan & Breen, Colin (2007). Maritime Ireland. An Archaeology of Coastal Communities. Stroud: Tempus. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-7524-2509-2.