Pacific Northwest English

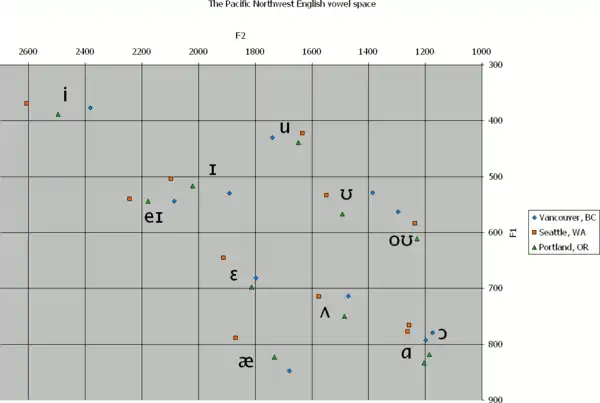

Pacific Northwest English (also known, in American linguistics, as Northwest English)[1] is a variety of North American English spoken in the U.S. states of Washington and Oregon, sometimes also including Idaho and the Canadian province of British Columbia.[2] Current studies remain inconclusive about whether Pacific Northwest English is a dialect of its own, separate from Western American English or even California English or Standard Canadian English,[3] with which it shares its major phonological features.[4] The dialect region contains a highly diverse and mobile population, which is reflected in the historical and continuing development of the variety.

| Pacific Northwest English | |

|---|---|

| Region | Northwestern United States (Oregon, Northern California and Washington) and Western Canada (British Columbia) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

History

The linguistic traits that flourish throughout the Pacific Northwest attest to a culture that transcends boundaries. Historically, this hearkens back to the early years of colonial expansion by the British and Americans, when the entire region was considered a single area and people of all different mother tongues and nationalities used Chinook Jargon (along with English and French) to communicate with each other. Until the Oregon Treaty of 1846, it was identified as being either Oregon Country (by the Americans) or Columbia (by the British).[5]

Linguists immediately after World War II tended to find few patterns unique to the Western region, as among other things, Chinook Jargon and other "slang words" (despite Chinook Jargon being an actual separate language in and of itself, individual words from it like "salt chuck", "muckamuck", "siwash" and "tyee" were and still are used in Pacific Northwest English) were pushed away in favour of having a "proper, clean" dialect.[6] Several decades later, linguists began noticing emerging characteristics of Pacific Northwest English, although it remains close to the standard American accent.

Phonology

Commonalities with both Canada and California

- Pacific Northwest English has all the phonological mergers typical of North American English and, more specifically, all the mergers typical of Western American English, including the cot–caught merger.

- Younger speakers of Pacific Northwest English also show features of the Canadian/California Vowel Shift, which move front vowels through a lowering of the tongue:

- /ɑ/ is backed and sometimes rounded to become [ɒ]. Most Pacific Northwest speakers have undergone the cot–caught merger. A notable exception occurs with some speakers born before roughly the end of World War II.

- There are also conditional raising processes of open front vowels. These processes are often more extreme than in Canada and the North Central United States.

- Before the velar nasal [ŋ], /æ/ becomes [e]. This change makes for minimal pairs such as rang and rain, both having the same vowel [e], differing from rang [ræŋ] in other varieties of English.

- Among some speakers in Portland and southern Oregon, /æ/ is sometimes raised and diphthongized to [eə] or [ɪə] before the nasal consonants [m] and [n]. This is typical throughout the U.S.

- While /æ/ raising is present in Canadian, Californian and Pacific Northwest English, differences exist between the groups most commonly presenting these features. /æ/ raising is more common in younger Canadian speakers and less common in younger Washingtonian speakers.[7]

Commonalities with Canada

These commonalities are shared with Canada and the North Central United States which includes the Minnesota accent.

- Traditional and older speakers may show certain vowels, such as [oʊ] as in boat and [eɪ] as in bait, with qualities much closer to monophthongs ([o] and [e]) than the diphthongs typical of most of the U.S.

- /ɛ/, and, in the northern Pacific Northwest, /æ/, become [eɪ] before the voiced velar plosive /ɡ/: egg and leg are pronounced to rhyme with plague and vague, a feature shared by many northern Midwestern dialects and with the Utah accent. In addition, sometimes bag will be pronounced bayg.[8]

Commonalities with California

- Back vowels of the California Shift: The Canadian/California Shift developing in Pacific Northwest English also includes these additional features only reminiscent of California English, but not Canadian English (especially among working-class young-adult females):[9]

- The close central rounded vowel [ʉ] or close back unrounded vowel [ɯ] for /u/, is found in Portland and some areas of Southern Oregon, but is generally not found further north, where the vowel remains the close back rounded [u].

- In speakers born around the 1960s, there is a tendency to move the tongue forward in the first element of the diphthong /oʊ/. This is reminiscent also of Midland, Mid-Atlantic, and Southern U.S. English.[10] This fronting does not appear before /m/ and /n/, for example, in the word home.[11]

- Absence of Canadian raising: For most speakers, both /aɪ/ and /aʊ/ remain lax before voiceless obstruents, although some variation has been reported. This likens the Pacific Northwest accent with Californian accents, and contrasts it with Canadian and some other American dialects (such as Philadelphia English).

Miscellaneous characteristics

- Some speakers perceive or produce the pairs /ɛn/ and /ɪn/ close to each other,[12] for example, resulting in a merger between pen and pin, most notably for some speakers in Eugene, Oregon and Spokane, Washington.[13]

Lexicon

Several English terms originated in or are largely unique to the region:

- cougar: mountain lion

- duff: forest litter[14]

- tolo: Sadie Hawkins dance[15]

- (high) muckamuck: an important person or person of authority, usually a pompous one (from Chinook Jargon, where it means "eats a lot; much food")

- potato bug: woodlouse[16]

- salt chuck: the ocean (from Chinook Jargon, where it means "salt water" or "the ocean"; today used on the radio).

- spendy: expensive[17]

- sunbreak: a passage of sunlight in the clouds during dark, rainy weather (typical west of the Cascade Mountains)[18]

- spodie: an outdoor high school party at which a mixture of alcoholic beverages (often with chopped fruit added as well) is sold by the cup and drunk (largely unique to the Seattle area).

See also

Notes

- Riebold, John M. (2014). "Language Change Isn't Only Skin Deep: Inter-Ethnic Contact and the Spread of Innovation in the Northwest" (PDF). Cascadia Workshop in Sociolinguistics 1 at University of Victoria. University of Washington. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 23, 2015.

- Riebold, John M. (2012). "Please Merge Ahead: The Vowel Space of Pacific Northwestern English" (PDF). Northwest Linguistics Conference 28. University of Washington. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 28, 2015.

- Ward (2003:87): "lexical studies have suggested that the Northwest in particular forms a unique dialect area (Reed 1957, Carver 1987, Wolfram and Shilling-Estes 1998). Yet the phonological studies that could in many ways reinforce what the lexical studies propose have so far been less confident in their predictions".

- Ward (2003:43–45)

- Meinig, Donald W. (1995) [1st pub. 1968]. The Great Columbia Plain (Weyerhaeuser Environmental Classic ed.). University of Washington Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-295-97485-9.

- Wolfram and Ward 2006, pg. 140

- Swan, Julia Thomas (February 1, 2020). "Bag Across the BorderSociocultural Background, Ideological Stance, and BAG Raising in Seattle and Vancouver". American Speech. 95 (1): 46–81. doi:10.1215/00031283-7587892. ISSN 0003-1283.

- Wassink, Alicia Beckford (March 2015). "Sociolinguistic Patterns in Seattle English". Language Variation and Change. 27 (1): 31–58. doi:10.1017/S0954394514000234. ISSN 0954-3945.

- Ward (2003:93)

- Conn, Jeff (2002). An investigation into the western dialect of Portland Oregon. Paper presented at NWAV 31, Stanford, California. Archived from the original on November 21, 2015.

- Ward (2003:44)

- Labov, Ash, Boberg 2006

- Labov et al. 2006. p. 68.

- Raftery, Isolde (December 23, 2014). A brief history of words unique to the Pacific Northwest. KUOW. Archived from the original on September 21, 2015.

Duff = The decaying vegetable matter, especially needles and cones, on a forest floor.

Fish wheel = A wheel with nets, put in a stream to catch fish; sometimes used to help fish over a dam or waterfall. - "Tolo Chapter History – University of Washington Mortar Board – Tolo Chapter".

- Vaux, Bert and Scott Golder. 2003. The Harvard Dialect Survey. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Linguistics Department.

- Do You Speak American? § Pacific Northwest. PBS. Archived from the original on July 23, 2015.

As Portlanders continue to front their back vowels, they will continue to go to the coast (geow to the ceowst), not the beach or the shore, as well as to microbrews, used clothing stores (where the clothes are not too spendy (expensive), bookstores (bik‑stores) and coffee shops (both words pronounced with the same vowel).

- Champagne, Reid (February 8, 2013). "Solar neighborhood projects shine in 'sunbreak' Seattle". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on November 21, 2015. Retrieved May 29, 2013.

[I]n this part of the world . . . sunshine is more frequently reported as ‘sunbreaks’.

References

- Boberg, Charles (2000). "Geolinguistic diffusion and the U.S.–Canada border". Language Variation and Change. 12 (1): 15. doi:10.1017/S0954394500121015.

- Wolfram, Walt; Ward, Ben, eds. (2005). American Voices: How Dialects Differ from Coast to Coast (1st ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 140, 234–236. ISBN 978-1-4051-2109-5. LCCN 2005017255. OCLC 56911940. OL 16950865W.

- Labov, William; Ash, Sharon; Boberg, Charles (2005). The Atlas of North American English: Phonetics, Phonology and Sound Change. Mouton de Gruyter. p. 68. ISBN 978-3-11-020683-8.

- Ward, Michael (2003). Portland Dialect Study: The Fronting of /ow, u, uw/ in Portland, Oregon (PDF). Portland State University. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 29, 2007.

Further reading

- Vowels and Consonants: An Introduction to the Sounds of Languages. Peter Ladefoged, 2003. Blackwell Publishing.

- Language in Society: An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. Suzanne Romaine, 2000. Oxford University Press.

- How We Talk: American Regional English Today. Allan Metcalf, 2000. Houghton Mifflin.

- Paulson, Tom (May 20, 2005). "Contrary to belief, local linguists say Northwest has distinctive dialect". Seattle Post‑Intelligencer. ISSN 0745-970X. Archived from the original on January 13, 2009.