Comparison of Asian national space programs

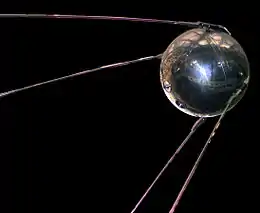

Several Asian national space programs are engaged in a race to achieve the scientific and technological advancements necessary for regular spaceflight, as well as to reap the strategic and economic benefits of space capability. This is sometimes referred to as the "Asian space race" in popular media,[1] an allusion to the Cold-War-era Space Race between the United States and the Soviet Union.

As in the previous Space Race, between the United States and the USSR, the motivations for the current push into space include national security, national pride, and commercial gain. As a result, several Asian countries have sent both unmanned satellites and humans into geocentric orbit and beyond.[2]

Although many Asian nations have taken steps toward a significant presence in space, three countries are forerunners: China, India, and Japan.[3]

Asian space agencies and programs

| Country | Official Name | Acronym | Founded | Terminated | Capabilities | Remarks | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Astronauts | Operates Satellites | Sounding Rockets capable | Recoverable Biological Sounding Rockets capable | ||||||

| Space Research and Remote Sensing Organization | SPARRSO | 1980 | — | No | Yes | No | No | [4] | |

| China National Space Administration (Chinese: 国家航天局) |

CNSA | 22 April 1993 | — | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | [5] | |

| Indian Space Research Organisation (Hindi: भारतीय अंतरिक्ष अनुसंधान संगठन) |

ISRO इसरो |

15 August 1969 | — | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | [6][7][8] | |

| Indonesian: Lembaga Antariksa dan Penerbangan Nasional (National Institute of Aeronautics and Space) |

LAPAN | 27 November 1964 | — | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | ||

| Iranian Space Agency (Persian: سازمان فضایی ایران) |

ISA | 2003 | — | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | [9][10][11] | |

| Israeli Space Agency (Hebrew: סוכנות החלל הישראלית) |

ISA סל"ה |

April 1983 | — | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | ||

| Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (Japanese: 宇宙航空研究開発機構) |

JAXA | 1 October 2003 | — | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | [12][13] | |

| Malaysian National Space Agency (Malay: Agensi Angkasa Negara) |

ANGKASA | 2002 | — | Yes | Yes | No | No | [14] | |

| Korean Committee of Space Technology (Korean: 조선우주공간기술위원회) |

KCST | 1980s | 2013 | No | Yes | Yes | No | [15][16][17] | |

| Pakistan Space and Upper Atmosphere Research Commission (Urdu: پاکستان خلائی و بالا فضائی تحقیقاتی کمیشن) |

SUPARCO سپارکو |

16 September 1961 | — | No | No | No | No | ||

| Philippine Space Agency | PhilSA | 8 August 2019 | — | No | Yes | No | No | [18] | |

| Korea Aerospace Research Institute (Korean: 한국항공우주연구원) |

KARI | 10 October 1989 | — | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | ||

| National Space Organization (Chinese: 國家太空中心) |

NSPO | 3 October 1991 | — | No | Yes | Yes | No | [19] | |

| Geo-Informatics and Space Technology Development Agency (Thai: สำนักงานพัฒนาเทคโนโลยีอวกาศและภูมิสารสนเทศ) |

GISTDA สทอภ |

3 November 2002 | — | No | Yes | No | No | [20] | |

Asian space powers

The countries that have independently and successfully launched satellites into orbit include Japan (1970), China (1970), India (1980), Israel (1988), Iran (2009), and North Korea (2012). Of these six Asian agencies, three countries—China, India, and Japan—possess the ability to launch heavy payloads into geosynchronous orbits, launch multiple and recoverable satellites, deploy cryogenic engines, and operate extraterrestrial exploratory missions.

China's first crewed spacecraft entered orbit in October 2003, making China the first Asian nation to send a human into space.[21] India expects to send its own vyomanauts into space in the Gaganyaan capsule by 2022.[22] India is the first Asian country to successfully launch a Mars orbiter mission and the first country in the world to do it on the first attempt.

The achievements of these space programs do not yet rival those of the former Soviet Union and the United States, although some experts believe Asia may soon lead the world in space exploration.[23]

Although Japan was the first program on Earth to launch a mission that returned samples from an asteroid, the existence of a space race in Asia is still debated, due to the lack of true spaceflight milestones. Although China denies that there is an Asian space race, there was competition between China and India in their attempts to be the first to launch a probe to Earth's moon within the first decade of the 21st century.[24] In January 2007, China became the first Asian space power to send an anti-satellite missile into orbit, destroying an aging Chinese Feng Yun 1C weather satellite in polar orbit. The resulting explosion sent a wave of debris hurtling through space at more than 6 miles per second.[25][26] In 2019, India, in operation Mission Shakti, did the same, shooting down its own Microsat-R satellite.[27] China and India tested their anti-satellite weapons in 2007 and 2019 respectively, making them the only countries other than the US and the USSR/Russia, to possess ASAT weapons.

A month later, Japan's space agency launched an experimental communications satellite designed to enable super-high-speed data transmission in remote areas.[25]

After the successful attainment of geostationary technology, India's ISRO launched its first moon mission, Chandrayaan-1, in October 2008, when it discovered ice water on the Moon.[28] On November 5, 2013, India then launched its maiden interplanetary mission, the Mars Orbiter Mission, to determine the composition of Mars's atmosphere and to detect methane. The spacecraft completed its journey on September 24, 2014, when it entered its intended orbit around Mars. ISRO became the fourth space agency in the world to send a spacecraft to Mars, following NASA, Roscosmos, and the ESA.

In addition to enhancing national prestige, countries are economically motivated to operate in space, frequently launching commercial satellites to enable communications, weather forecasting, and atmospheric research. According to a 2006 report by the Space Frontier Foundation, the "space economy" is estimated to be worth about $180 billion, with more than 60% of space-related economic activity coming from commercial goods and services.[2]

Both China and India have proposed the initiation of commercial launch services.

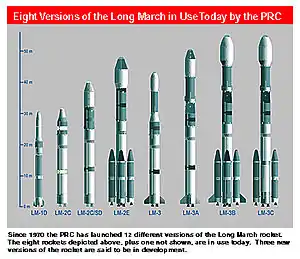

China

China has a space program with an independent human spaceflight capability, having successfully developed a sizable family of Long March rockets. It has launched two lunar orbiters: Chang'e 1 and Chang'e 2. On 2 December 2013, China launched a modified Long March 3B rocket to the moon, carrying a Chang'e 3 Moon lander and its rover Yutu, which successfully performed a soft landing and rover operations. With the success of the mission, China became the third country to do so; it planned to retrieve further samples in 2017.[29] In 2011, China embarked on a program to establish a crewed space station, starting with the launch of Tiangong 1 and followed by Tiangong 2 in 2016. In 2011, in a joint mission with Russia, China launched a Mars orbiter, Yinghuo-1, which failed to leave Earth orbit. Nevertheless, the 2020 Chinese Mars Mission—with an orbiter, a lander, and a rover—has been approved by the Chinese government. Launched in July 2020, the mission is on a course to Mars.[30] China has collaborative projects with Russia, the ESA, and Brazil, launching commercial satellites for other countries. Some analysts suggest that the Chinese space program is linked to the nation's efforts at developing advanced military technology.[31]

China's advanced technology is the result of the integration of various related technological experiences. Early Chinese satellites such as the FSW series have undergone many atmospheric reentry tests. In the 1990s, China was conducting commercial launches, resulting in more launch experiences and a high success rate following the decade. China has aimed to undertake scientific development in fields including Solar System exploration, with China's Shenzhou 7 spacecraft successfully performing an EVA in September 2008. China's Shenzhou 9 spacecraft successfully completed a crewed docking in June 2012. Furthermore, China's Chang'e 2 explorer became the first object to reach the Sun-Earth Lagrangian point, in August 2011, as well as becoming the first probe to explore both the Moon and asteroids by making a flyby of the asteroid 4179 Toutatis. China has launched DAMPE, the most capable dark matter explorer to date, in 2015, in addition to the world's first quantum communication satellite, QUESS, in 2016.

India

.jpg.webp)

India's interest in space travel began in the early 1960s, when scientists launched a Nike-Apache rocket from TERLS, Kerala.[32][33] Under Vikram Sarabhai, the program focused on the practical uses of space in increasing the standard of living by sending remote sensing and communications satellites into orbit.[34]

The first Indian to travel in space was Rakesh Sharma, who flew aboard Soyuz T-11, launched 2 April 1984 from the USSR.[35]

Just several days after the aforementioned mission, China said that it would send a human into orbit in the second half of 2003; Indian Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee publicly urged his country's scientists to work towards sending a man to the Moon.[36] India successfully sent its first probe to the Moon, known as Chandrayaan-1, in October 2008, which helped to find the presence of water in the Moon.[37] The nation also launched its second Moon mission, Chandrayaan-2, to the south pole of the Moon.[38][39]

ISRO launched its Mars Orbiter Mission (informally called "Mangalyaan") on November 5, 2013, successfully entering orbit around Mars on September 24, 2014. India is the first country in Asia, and the fourth in the world, to perform a successful Mars mission. It is also the only one to do so on the first attempt, at a record low cost of $74 million.[40]

ISRO has demonstrated its re-entry technology and, as of 2020, has launched as many as 175 foreign satellites belonging to global customers from 20 countries, including the US, Germany, France, Japan, Canada, and the U.K. All of these have been launched successfully by PSLVs so far, meaning that the country's scientists have gained significant expertise in space technologies. In June 2016, India set a record by launching 20 satellites simultaneously.[41] The PSLVs possess a success rate of more than 90%, having had their 35th successful mission in a row, out of 39 total missions, as of February 2017.

India broke the world record by successfully placing 104 satellites in Earth's orbit from a single rocket launch (PSLV-C37) on February 15, 2017, which almost tripled the previous record of 37, which had been held by Russia.[42][43]

Recent reports indicate that human spaceflight is planned for December 2021, with a spacecraft called Gaganyaan, which will embark upon a domestically developed GSLV-III rocket.[44] The ISRO is also planning to send orbiters to Venus and Mars in the near future. India has successfully tested an anti-satellite missile, making it the fourth country to do so.

Japan

Japan has been cooperating with the United States on missile defense since 1999. North Korean nuclear and Chinese military programs represent a serious issue for Japan's foreign relations.[45] Japan is working on military and civilian space technologies, developing missile defense systems and new generations of military spy satellites, as well as planning for the implementation of crewed stations on the Moon.[46] Japan started to construct spy satellites after North Korea test-fired a Taepodong missile over Japan in 1998. The North Korean government claimed the missile was merely launching a satellite into space, accusing Japan of causing an arms race.[47] The Japanese constitution, adopted after World War II, limits military activities to defensive operations; although in May 2007, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe called for a bold review of the Japanese Constitution to allow the country to take a larger role in global security and foster a revival of national pride.[48] Japan has not yet developed its own crewed spacecraft and does not have a program in place to develop one. The Japanese did develop a space shuttle, HOPE-X, to be launched by the conventional space launcher H-II, but the program was postponed and eventually cancelled. Then, the simpler crewed capsule Fuji was proposed but not adopted. Pioneer projects—including the single-stage to orbit, reusable launch vehicle, horizontal-takeoff-and-landing ASSTS and the vertical takeoff and landing Kankoh-maru—were developed but have also not been adopted. A new, more conservative JAXA crewed spacecraft project is supposed to be launched by 2025 as part of Japan's plan to send human missions to the Moon. Shinya Matsuura is doubtful about the Japanese human Moon project, suspecting the project is a euphemism for participation in the American Constellation program.[49] JAXA planned to send a humanoid robot, such as ASIMO, to the Moon within the next decade, in the hopes of using both automated and remote-controlled machines to build their planned moon base.[49][50]

Other Asian nations

Iran

Iran has developed its own satellite launch vehicle, named the Safir SLV, based on the Shahab series of IRBMs. On 2 February 2009, Iranian state television reported that Iran's first domestically manufactured satellite, Omid (from the Persian امید, meaning "hope") had been successfully launched into low Earth orbit by a version of Iran's Safir rocket, the Safir-2.[51] The launch coincided with the 30th anniversary of the Iranian Revolution. Iran is also developing a new rocket, named Simorgh.

Israel

On 19 September 1988, Israel became the eighth country in the world to build its own satellite and launcher. Israel launched its first satellite, Ofeq-1, using an Israeli-built Shavit three-stage launch vehicle.[52] The launch was the high point of a process that began in 1983 with the establishment of the Israel Space Agency under the aegis of the Ministry of Science. Space research by university-based scientists had begun in the 1960s, providing a ready-made pool of experts for Israel's foray into space. Since then, local universities, research institutes, and private industry, backed by the Israel Space Agency, have made progress in space technology. The agency's role is to support "private and academic space projects, coordinate their efforts, initiate and develop international relations and projects, head integrative projects involving different bodies, and create public awareness for the importance of space development."[53]

North Korea

North Korea has many years of experience with rocket technology, which it has passed along to Pakistan and other countries. On 12 December 2012, North Korea placed its first satellite in orbit with the launch of Kwangmyŏngsŏng-3 Unit 2. On 12 March 2009, North Korea signed the Outer Space Treaty and the Registration Convention,[54] after a previous declaration of making preparations for the launch of Kwangmyongsong-2. North Korea twice announced satellite launches: Kwangmyŏngsŏng-1 on 31 August 1998 and Kwangmyŏngsŏng-2 on 5 April 2009. Neither of these claims were confirmed by the rest of the world, but the United States and South Korea believe they were tests of military ballistic missiles. The North Korean space agency is the Korean Committee of Space Technology, which operates the Musudan-ri and Tongch'ang-dong Space Launch Center rocket launching sites, and has developed the Baekdusan-1 and Unha (Baekdusan-2) space launchers and Kwangmyŏngsŏng satellites. In 2009 North Korea announced several future space projects, including human space flights and the development of a crewed, partially reusable launch vehicle.[55] The successor to the Korean Committee of Space Technology, National Aerospace Development Administration (NADA), successfully launched an Unha-3 launch vehicle in February 2016, placing the Kwangmyŏngsŏng-4 satellite in orbit.

Indonesia

LAPAN is responsible for long-term civilian and military aerospace research for Indonesia, which in July 1976 became the first developing country to operate its own domestic satellite system.[56] In October 1985, Indonesian scientist, Pratiwi Sudarmono was selected to take part in the NASA Space Shuttle mission STS-61-H as a Payload Specialist. Taufik Akbar was her backup on the mission. However, after the Challenger disaster the deployment of commercial satellites—such as the Indonesian Palapa B-3, planned for the STS-61-H mission—was canceled; and so the mission never took place. The satellite was later launched with a Delta rocket.[57] For over two decades, Indonesia has managed satellites and domain-developed small scientific-technology satellites LAPAN and telecommunication satellites Palapa, which were built by Hughes (now Boeing Satellite Systems) and launched from the US on Delta rockets or from French Guiana using Ariane 4 and Ariane 5 rockets. It has also developed sounding rockets and has been trying to develop small orbital space launchers. The LAPAN A1 in 2007 and LAPAN A2 satellites were launched by India in 2015.[58] Indonesia has undertaken programs to develop and use their own small space launch vehicle Pengorbitan (RPS-420).[59][60]

South Korea

South Korea is a more recent player in the Asian space race.[61] In August 2006 South Korea launched its first military communications satellite, the Mugunghwa-5. The satellite was placed in geosynchronous orbit and collects surveillance information about North Korea.[62] The South Korean government is spending hundreds of millions of dollars on space technology and was due to launch its first space launcher, the Korea Space Launch Vehicle, in 2008.[63] South Korea's government justifies the cost by pointing to the long-term commercial benefits, as well as enhanced national pride. South Korea has long seen North Korea's significantly longer missile range as a serious threat to its national security. With the nation's first astronaut launched into space, Lee So-yeon, South Korea gained confidence in entering the Asian space race. They have completed the construction of Naro Space Center. South Korea is now attempting to build satellites and rockets with local technology.[64] South Korea is pursuing a space program that could defend the peninsula while lessening their dependency on the United States.

Turkey

Turkey's first Göktürk satellite was launched on December 18, 2012. The satellite is capable of taking images which have a resolution of over two meters per pixel, thus making Turkey the second nation in the world capable of such a feat, after the United States. Turkey is also developing an orbital launch system known as UFS.[65]

Other nations and regions

Other minor space-faring countries are Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Malaysia. On 7 June 1962, with the launch of the Rehbar-I rocket, Pakistan became the tenth country in the world to successfully launch an unmanned spacecraft. SUPARCO has launched several sounding rockets. Pakistan's first satellite, Badr-I, was launched from China in 1990. Badr-B was launched in 2001 from Baikonur Cosmodrome, using a Ukrainian Zenit-2 rocket. In 2011, Paksat-1R—which was contracted for, built, and launched by China—became Pakistan's first communication satellite.[66] Under its Space programme 2040, Pakistan aims to operate five geostationary and six low-earth-orbit satellites. Development of a satellite launch vehicle is not planned.

In 2018, with the launch of the Bangabandhu-1 satellite, which was purchased abroad, Bangladesh began operating its first communication satellite. The Bangladesh Space Agency intends to launch satellites after 2020. Bangladesh's government has stressed that the country seeks an "entirely peaceful and commercial" role in space.[67]

Timeline of national firsts

| – Indigenous crewed missions | – Human missions | – Lunar or Interplanetary missions | – Other missions |

| Date | Nation | Name | Asian First | World achievements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 February 1970 | Ohsumi | Satellite | The smallest satellite launch vehicle (L-4S; 9.4t weight, 0.74m diameter) until SS-520 | |

| 24 February 1975 | Taiyo | Solar probe | ||

| 26 October 1975 | FSW-0 | Satellite recovery[68] | ||

| 26 October 1975 | FSW-0: – 10m (1975) FSW-1B: – 4m (1992)[69] Beidou: – 0.5m (till 2007)[70] |

High resolution imaging satellite | ||

| 8 July 1976 | Palapa A1 | Geosynchronous satellite (launched by NASA) | ||

| 23 February 1977 | N-I | Geosynchronous launch | ||

| 21 February 1979 | Hakucho | Space observatory | ||

| 23 July 1980 | Phạm Tuân | Asian in space (Soyuz 37) | ||

| 20 September 1981 | FB-1 | Simultaneous satellite launch[71] | ||

| 8 January 1985 | Sakigake | Leaving Earth orbit, comet fly-by | First interplanetary launch from a country other than the USSR or US, using a solid-fuel rocket (M-3SII) | |

| 18 March 1990 | Hiten | Lunar fly-by | First lunar probe from a country other than the USSR or US | |

| 19 March 1990 | Hagoromo | Reach lunar orbit (assumed) | ||

| 7 April 1990 | CZ-3 | Commercial launch (AsiaSat 1) | ||

| 2 December 1990 | Toyohiro Akiyama | Private space traveler (Soyuz TM-11) | First commercial sponsor (Tokyo Broadcasting System) for a human spaceflight | |

| 12 September 1992 | Mamoru Mohri | First astronaut trained by an Asian space program (STS-47) | ||

| 10 April 1993 | Hiten | Intentional lunar impact | The first aerobraking test[72] | |

| 8 July 1994 | Chiaki Mukai | Asian woman in space (STS-65) | ||

| 11 February 1996 | HYFLEX | Lifting body spaceplane demonstrator | ||

| 19 November 1997 | Takao Doi | Spacework (STS-87) | ||

| 28 November 1997 | ETS-VII | Rendezvous docking | ||

| 3 July 1998 | Nozomi | Martian mission (Failure) | ||

| 30 October 2000 | Beidou | Satellite navigation system | ||

| 10 September 2002 | Kodama[73] | Data relay satellite (with ESA) | ||

| 15 October 2003 | Yang Liwei | First man in space launched by an Asian space program | ||

| 15 October 2003 | Shenzhou 5 | Crewed spacecraft | ||

| 19 November 2005 | Hayabusa | Soft-landed probe on extraterrestrial object. First sample return mission by an Asian country. | The first asteroid ascent, sample return from an asteroid | |

| 11 January 2007 | FY-1C | ASAT test | Highest in history with altitude 865 km, also the fastest with speed 18k miles | |

| 23 February 2008 | WINDS | Internet satellite | The fastest internet satellite[74] | |

| 11 March 2008 | Japanese Experiment Module | Crewed space station module (STS-123, STS-124, STS-127) | The world's largest pressurized volume in space[75] | |

| 25 April 2008 | Tianlian I | Indigenous Tracking & Data Relay Satellite System First TDRS system to support crewed missions |

||

| 27 September 2008 | Zhai Zhigang (Shenzhou 7) | Indigenous EVA | ||

| 27 September 2008 | BanXing | Crewed spacecraft-launched satellite | ||

| 23 January 2009 | GOSAT | Greenhouse gas explorer[76] | ||

| 10 September 2009 | HTV-1 | Dedicated cargo spacecraft | ||

| 20 May 2010 | Akatsuki | First Asian Venus mission | ||

| 21 May 2010 | IKAROS | Solar sail | The first spacecraft to successfully demonstrate solar-sail technology in interplanetary space | |

| 25 August 2011 | Chang'e 2 | Lunar probe with extended deep space missions (asteroid mission to 4179 Toutatis). | ||

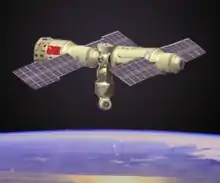

| 29 September 2011 | Tiangong-1 | First independent Asian space station | ||

| 18 June 2012 | Shenzhou 9 | First crewed space docking by an Asian country (with Tiangong-1) | ||

| 14 December 2013 | Chang'e 3/Yutu | First lunar soft landing and lunar rover by an Asian country | First lunar soft landing in 21st century | |

| 24 September 2014 | Mars Orbiter Mission | First successful Mars mission by an Asian country | First Martian mission by a country to succeed on the first attempt. Third individual country to do so after the USSR and the USA. | |

| 20 October 2018 | Mio | First Asian Mercury mission (with ESA), planned orbital insertion in December 2025 | ||

| 3 January 2019 | Chang'e 4 | First soft landing on the far side of the Moon | First soft landing on the far side of the Moon by any country. Landed with Yutu-2 rover. | |

| 23 July 2020 | Tianwen-1 | First Asian Mars lander and rover, planned arrival in February 2021 | ||

| 5 December 2020 | Chang'e 5 | First lunar ascent, lunar rendezvous and docking and lunar sample return by an Asian country | First automated lunar rendezvous and docking by any country. Lunar sample-return mission. |

Other achievements

- First Asian country to collaborate on the International Space Station –

Japan

Japan - First Asian country to launch over 100 satellites from a single rocket –

India[77][78]

India[77][78]

| First success | LEO | GTO / GEO | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11 Feb 1970 | First launch was 1966 (failed 4 times). | ||

| 24 Apr 1970 | First launch failed in 1969. | ||

| 26 Jul 1975 | Suborbital flight was performed in 1972. | ||

| 12 Aug 1986 | First stage was a license-built Delta rocket. | ||

| 16 Jul 1990 | |||

| 3 Feb 1994 | |||

| 20 Aug 1997 | |||

| 18 Dec 2006 | |||

| 10 Sep 2009 | |||

| 3 Nov 2016 | |||

| 5 May 2020 | |||

Comparison of key technologies

Records of each country are listed by chronological order unless otherwise noted.

Launch vehicle technology

- First successful independent launches (rocket/satellite)

| Country | Year | Mission |

|---|---|---|

| 1970 | Lambda-4S/Ohsumi | |

| 1970 | Long March 1/Dong Fang Hong I | |

| 1980 | SLV/Rohini D1 | |

| 1988 | Shavit/Ofeq 1 | |

| 2009 | Safir-1/Omid | |

| 2012 | Unha-3/Kwangmyŏngsŏng-3 Unit 2 |

- Solid fuel rockets

| Country | Rocket | Burn time | Specific impulse (Vac.) | Thrust (Vac.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S200 booster rocket stage[80] | 130s | 274.5s | 5,150 kN (1,160,000 lbf) | |

| SRB-A series solid fueled rocket boosters | 100s | 280s | 2,260 kN (510,000 lbf) | |

| Shavit's first stage | 82s | 280s | 1,650 kN (370,000 lbf) | |

| Kuaizhou series of launch vehicles | ||||

| Long March 11 launch system |

- Cryogenic and semi-cryogenic rocket engines

| Country | Engine | Thrust (vac.) | Stage | Cycle | Active | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LE-5 cryogenic engine | LE-5 — 102.9 kN (23,100 lbf) ---------- LE-5A — 121.5 kN (27,300 lbf) ---------- LE-5B — 144.9 kN (32,600 lbf) |

Upper stage | 5 — Gas generator 5A and 5B — Expander |

1986 — present | In service | |

| LE-7 cryogenic engine | LE-7 — 1,078 kN (242,000 lbf) ---------- LE-7A — 1,074 kN (241,000 lbf) |

Booster | Staged combustion | 1994 — present | In service | |

| YF-73 cryogenic engine | 44.15 kN (9,930 lbf) | Upper stage | Gas generator | 1987–2000 | Retired | |

| YF-75 cryogenic engine | 78.45 kN (17,640 lbf) | Upper stage | Gas generator | 1994 — present | In service | |

| YF-75D cryogenic engine | 88.26 kN (19,840 lbf) | Upper stage | Expander | 2016 — present | In service | |

| YF-77 cryogenic engine | 700 kN (160,000 lbf) | Booster | Gas generator | 2016 — present | In service | |

| CE-7.5 cryogenic engine | 73.5 kN (16,500 lbf) | Upper stage | Staged combustion | 2014 — present | In service | |

| CE-20 cryogenic engine | 200 kN (45,000 lbf) | Upper stage | Gas-generator | 2017 — present | In service | |

| SCE-200 semi-cryogenic engine | 2,030 kN (460,000 lbf) | Booster | Staged combustion | After 2022 | Under development |

- Capability of Launch Vehicle (in active)

| Country | Highest payload capacity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LEO | GTO | |||||

| Launch Vehicle | Payload capacity | Active since | Launch Vehicle | Payload capacity | Active since | |

| CZ-5 | 25,000 kg (55,000 lb) | 2016 | CZ-5 | 14,000 kg (31,000 lb) | 2016 | |

| H-IIB | 16,500 kg (36,400 lb) | 2009 | H-IIB | 8,000 kg (18,000 lb) | 2009 | |

| GSLV MkIII | 10,000 kg (22,000 lb) | 2017 | GSLV MkIII | 4,000 kg (8,800 lb) | 2017 | |

| Shavit | 800 kg (1,800 lb) | 1988 | Not any yet | |||

| Unha-3 | 200 kg (440 lb) | 2009 | Not any yet | |||

| Safir-1B | 50 kg (110 lb) | 2008 | Not any yet | |||

- Biggest multi-satellite simultaneous launches (by number)

| Country | Number of satellites | Year | Launch Vehicle | Flight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 104 | 2017 | PSLV-XL | C37 | |

| 20 | 2015 | Long March 6 | 1 | |

| 8 | 2009 | H-IIA | F15 |

- First flight of space shuttles

- Including shuttle-shaped hyper-sonic reentry vehicles reach to space.

| Country | Spaceplane | First flight mission | Year | Program status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HOPE-X | HYFLEX | 1996 | Cancelled | |

| Various | Shenlong | 2007 | Ongoing | |

| RLV–TD | Hypersonic Flight Experiment | 2016 | Under development |

Satellite technology

- Payloads in orbit by number

| Country | Active | In orbit | Decayed | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 352 | 407 | 84 | 491 | |

| 90 | 183 | 65 | 248 | |

| 64 | 101 | 12 | 113 | |

| 17 | 20 | 6 | 26 | |

| 15 | 22 | 5 | 27 |

- Optical satellite imagery (by highest available resolution)

| Country | Resolution | Satellite | Year launched |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.25 meter | Cartosat-3 | 2019 | |

| 0.4 meter | IGS Optical 5V | 2013 | |

| 0.5 meter | Ofeq 9 | 2010 | |

| 0.5 meter | Gaofen 9 | 2015 | |

| 0.7 meter | KOMPSAT-3 | 2012 | |

| 150 meters | Rasad 1 | 2011 |

- Radar satellite imagery (by resolution)

| Country | Resolution | Satellite | Year launched |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.35 meter | RISAT-2BR1 | 2019 | |

| 0.5 meter x 0.3 meter | RISAT-2B | 2019 | |

| 0.5 meter | IGS R-5 | 2017 | |

| 0.5 | TecSAR | 2008 | |

| 0.5 meter | Yaogan 29 | 2015 | |

| 1 meter | KOMPSat-5 | 2013 |

- Communications satellite technology

| Country | Satellite | Transponders | Mass | Power | Year launched |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIGCOMSAT 1R | 28 | 5,150 kg (11,350 lb) | 10.5 kW | 2011 | |

| ST-2 | 51 | 5,090 kg (11,220 lb) | 2011 | ||

| GSAT-16 | 48 | 3,100 kg (6,800 lb) | 5.6 kW | 2014 | |

| GSAT-11 | 40 | 5,854 kg (12,906 lb) | 13.6 kW | 2018 |

- Solar Sail spacecraft

| Country | Satellite | Type | Year launched |

|---|---|---|---|

| IKAROS | Extraterrestrial exploration | 2010 |

- Spacecraft powered by indigenous plasma thrusters

| Country | Spacecraft (engine) | Power | Thrust | Specific impulse | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ETS-IV (Unnamed teflon pulsed plasma thruster) | 20 W | 300s | 1981 | ||

| Space Flyer Unit (EPEX, magnetoplasmadynamic thruster) | 430 W | 12.9 mN | 600s | 1995 | |

| Dongfeng 5 ballistic rocket (MDT-2A, teflon pulsed plasma thruster) | 5 W | 280s | 1981 |

- Spacecraft powered by indigenous ion thrusters

| Country | Spacecraft | Power | Thrust | Specific impulse | Year launched |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hayabusa (μ-10, microwave ion thrusters) | 350 W | 8 mN | 3200s | 2003 | |

| Shijian 9A (LIPS-200, ring-cusp magnetic field ion thruster) | 1 kW | 40 mN | 3000s | 2012 | |

| GSAT-20 (Full) | 2020 (Planned) |

- Spacecraft powered by indigenous Hall thrusters

| Country | Spacecraft | Power | Thrust | Specific impulse | Year launched |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DubaiSat-2 | 0.3 kW | 7 mN | 1000s | 2013 | |

| Shijian 17 (HEP-100MF, magnetic focusing hall thruster) | 1.4 kW | 1850s | 2016 | ||

| Shijian 17 (LHT-100) | 1.35 kW | 80 mN | 1600s |

Human spaceflight and rendezvous space docking and berthing capabilities

- First indigenous human spaceflights

| Country | Program | First successful human spaceflight | Status | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Period | Year | Spacecraft | ||

| Project 714 | 1968–72 | N/A | Shuguang-1 | Cancelled | |

| Project 873 | 1978–80 | N/A | Piloted FSW satellite | Cancelled | |

| Project 921/Shenzhou | 1992–present | 2003 | Shenzhou 5 | Ongoing | |

| Indian Human Spaceflight Programme | 2007–present | 2021 (Planned) Before August 2022 (Scheduled) |

Gaganyaan | Ongoing | |

- Independent human spaceflights

| Country | Total persons | Total flights |

|---|---|---|

| 11 | 11 |

- First independent extravehicular activity

| Country | Spacecraft involved | Year |

|---|---|---|

| Shenzhou 7 | 2008 |

- First independent Space rendezvous

| Country | Uncrewed rendezvous | crewed rendezvous | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spacecraft involved | Year | Spacecraft involved | Year | |

| ETS-VII | 1997 | |||

| Shenzhou 8 & Tiangong 1 | 2011 | Shenzhou 9 & Tiangong 1 | 2012 | |

| SPADEX | 2020 (Planned) | |||

- First space habitation module

| Country | Spacecraft | Year launched |

|---|---|---|

| Kibo | 2008 | |

| Tiangong 1 | 2011 | |

| Indian Space Station | ~2030 (Proposed) |

- First Space laboratory

| Country | Spacecraft | Year |

|---|---|---|

| Kibo | 2009 | |

| Tiangong 2 | 2016 | |

| Indian Space Station | ~2030(Proposed) |

- Resupply spacecraft

| Country | Spacecraft | Launch payload | Year launched |

|---|---|---|---|

| HTV | 6,000 kg (13,000 lb) | 2009 | |

| Tianzhou | 6,500 kg (14,300 lb) | 2017 |

Lunar exploration

- First orbiters to the Moon

| No. | Country | Spacecraft | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hiten/Hagoromo | 1990 | |

| 2 | Chang'e 1 | 2007 | |

| 3 | Chandrayaan-1 | 2008 | |

| TBD | Korea Pathfinder Lunar Orbiter | 2020 (Planned) |

- First intentional Moon landings

| No. | Country | Spacecraft | Year | Landing type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hiten | 1993 | Controlled impact | |

| 2 | Moon Impact Probe | 2008 | Controlled impact | |

| 3 | Chang'e 1 | 2009 | Controlled impact |

- First Lunar soft landings/Lunar rovers

| No. | Country | Spacecraft | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chang'e 3/Yutu | 2013 | |

| TBD | Beresheet | 2019 (Failed) | |

| TBD | Chandrayaan-2/Pragyan | 2019 (Failed) | |

| Chandrayaan-3 | 2021 (Planned) | ||

| TBD | Lunar Polar Exploration Mission | 2024 (Planned) |

Interplanetary exploration missions

- First probes to Mercury

| No. | Country | Spacecraft | Year | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBD | Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter | 2018 (en route) | Orbiter |

- First probes to Venus

| No. | Country | Spacecraft | Year | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Akatsuki | 2015 | Orbiter | |

| TBD | Shukrayaan-1 | 2024 or 2026 (Planned) | Orbiter with aerobots |

- First orbiters to Mars

| No. | Country | Spacecraft | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mars Orbiter Mission | 2013[87] | |

| TBD | Nozomi | 1998 (Failed) | |

| TBD | Yinghuo-1 | 2011 (Failed)[88] | |

| Tianwen-1 | 2020 (en route) | ||

| TBD | Hope Mars Mission | 2020 (en route) |

- First intentional Mars landing

| No. | Country | Spacecraft | Year | Landing type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBD | Mars Global Remote Sensing Orbiter and Small Rover | 2021 (en route) | Soft landing | |

| TBD | Mars Orbiter Mission 2 | 2024 (Planned)[89] | TBD |

- First Asteroid explorations

| No. | Country | Spacecraft | Year | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hayabusa | 2003 | Sample return | |

| 2 | Chang'e 2 | 2012 | Flyby |

| Nation | Multi-satellite simultaneous launches | Launch of foreign satellite | Geostationary launches | Atmos- pheric reentry | Rendezvous dockings in orbit | Satellite navigation system | Data relay satellites | Martian missions | Solar Space Missions | Space observatories |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1981 (FB-1)[90] 3 Sats | 1990 CZ-2E | 1984 Dong Fang Hong 02 (by CZ-3) | 1975 FSW-0 | 2011 Tiangong 1 | 2000 Beidou | 2008 Tianlian I | 2011 Yinghuo-1 (Failure) | (planned) Solar Space Telescope | 2017 Space Hard X-Ray Modulation Telescope | |

| 1999 (PSLV-CA C2) 3 Sats |

1999 PSLV-C2 | 2001 Kalpana-1 (by PSLV) | 2007 SRE-1 | SPADEX

(planned) |

2013 IRNSS[91] | IDRSS

(Planned) |

2013 Mangalyaan[87] (orbiter) | 2021 (planned) Aditya-L1 | 2015 Astrosat | |

| 1986 (H-I H15F)[92] 3 Sats | 2002 H-IIA | 1977 ETS-II[93] (by N-I) | 1994 OREX | 1997 ETS-VII[94] | 2010 QZSS[95] | 2002 Kodama | 1998 Nozomi (orbiter) (Failure) | 1975 Taiyo[96] | 1979 Hakucho |

? : Date is assumed

Only projects with under-development or above status have been listed

Asian orbital launch systems

Orbital launch systems from Asian national space agencies

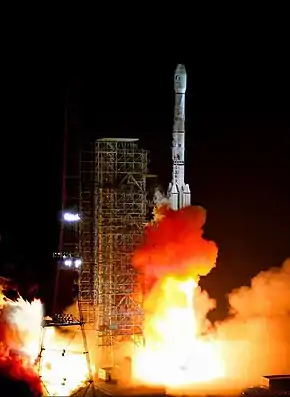

Long March 3B lifting off from Xichang Satellite Launch Center.

Long March 3B lifting off from Xichang Satellite Launch Center..jpg.webp)

The list documents launch systems developed or used by national space agencies only and not private spaceflight companies.

- Legend

- Under developmentOperationalRetired/Cancelled

| Launch system | Country of origin | Class and type | Payload capacity | Maiden flight | Manufacturer | Status | Ref | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LEO (Orbit) | GTO | Other | ||||||||

| Al-Abid | Small lift expendable launch vehicle | 100 kg (220 lb) to 300 kg (660 lb) (200 km (120 mi) to 500 km (310 mi) | N/A | 1989 | Space Research Center, Baghdad | Abandoned | [97] | |||

| Augmented Satellite Launch Vehicle | Small lift expendable launch vehicle | 150 kg (330 lb) (400 km (250 mi)) | N/A | 1987 | ISRO | Retired | [98] | |||

| Epsilon | Small lift expendable launch vehicle | 1,500 kg (3,300 lb) (250 km (160 mi)x500 km (310 mi)) 700 kg (1,500 lb) (500 km (310 mi)) |

590 kg (1,300 lb) to 500 km (310 mi) (SSO) | 2013 | JAXA/IHI | In service | [99] | |||

| Feng Bao 1 | Medium lift expendable launch vehicle | 2,500 kg (5,500 lb) | 1972 | Shanghai Bureau No.2 | Retired | [100] | ||||

| Geosynchronous Satellite Launch Vehicle | GSLV Mk I | Medium lift expendable launch vehicle | 5,000 kg (11,000 lb) | 2,150 kg (4,740 lb) | 2001 | ISRO | Retired | [101] | ||

| GSLV Mk II | 5,000 kg (11,000 lb) | 2,700 kg (6,000 lb) | 2010 | ISRO | In service | |||||

| Geosynchronous Satellite Launch Vehicle Mark III | Medium lift expendable launch vehicle | 10,000 kg (22,000 lb) | 4,000 kg (8,800 lb) | 2014 (Suborbital) 2017 (Orbital) |

ISRO | In service | [102] | |||

| GX | Medium lift expendable launch vehicle | 3,600 kg (7,900 lb) | 1,814 kg (3,999 lb) to 800 km (500 mi) SSO | N/A | JAXA/ULA/IHI | Cancelled | [103] | |||

| H-I | Medium lift expendable launch vehicle | 3,200 kg (7,100 lb) | 1,100 kg (2,400 lb) | 1986 | Mitsubishi Heavy Industries/McDonnell Douglas | Retired | [104] | |||

| H-II | H-II | Medium lift expendable launch vehicle | 10,060 kg (22,180 lb) | 3,930 kg (8,660 lb) | 1994 | Mitsubishi Heavy Industries | Retired | [105] | ||

| H-IIA | 10,000 kg (22,000 lb) to 15,000 kg (33,000 lb) | 4,100 kg (9,000 lb) to 6,000 kg (13,000 lb) | 2001 | Mitsubishi Heavy Industries/ATK | In service | [106] | ||||

| H-IIB | 16,500 kg (36,400 lb) | 8,000 kg (18,000 lb) | 2009 | Mitsubishi Heavy Industries | In service | [107] | ||||

| H3 | Medium lift expendable launch vehicle | >8,000 kg (18,000 lb) | >4,000 kg (8,800 lb) to SSO (Minimum configuration) | 2020 (Planned) | Mitsubishi Heavy Industries | Under development | [108] | |||

| J-I | Experimental expendable launch vehicle | – | – | 1,054 kg (2,324 lb) along 1,300 km (810 mi) downrange. | 1996 | NASDA/ISAS | Retired | [109] | ||

| Jielong-1 | Small lift expendable launch vehicle | N/A | 150 kg (330 lb) to 700 km (430 mi) (SSO) | 2019 | CALT | In service | [110] | |||

| Kaituozhe | Kaituozhe-1 | Small lift expendable launch vehicle | 100 kg (220 lb) | Not applicable | 2002 | CASC | Retired | [111] | ||

| Kaituozhe-2 | Small lift expendable launch vehicle | 800 kg (1,800 lb) | 2017 | In service | [112] | |||||

| Kaituozhe-2A | Medium lift expendable launch vehicle | 2,000 km (1,200 mi) | Unconfirmed | Unknown | ||||||

| Kuaizhou | Kuaizhou 1 | Small lift expendable launch vehicle | N/A | 430 kg (950 lb) to 500 km (310 mi) (SSO) | 2013 | CASC | In service | [113][114] | ||

| Kuaizhou-1A | Small lift expendable launch vehicle | 300 kg (660 lb) | N/A | 250 kg (550 lb) to 500 km (310 mi) (SSO) 200 kg (440 lb) to 700 km (430 mi) (SSO) |

2017 | In service | ||||

| Kuaizhou-11 | Small lift expendable launch vehicle | 1,500 kg (3,300 lb) | 1,000 kg (2,200 lb) to 700 km (430 mi) (SSO) | 2019–20 (Planned) | Under development | [115] | ||||

| Kuaizhou-21 | Heavy lift expendable launch vehicle | 20,000 kg (44,000 lb) | 2025 (Projected) | Under development | [113][116] | |||||

| Kuaizhou-31 | Super heavy lift expendable launch vehicle | 70,000 kg (150,000 lb) | TBD | Under development | ||||||

| Lambda (rocket family) | Small lift expendable launch vehicle | 26 kg (57 lb) | 1970 | ISAS/Nissan | Retired | [117] | ||||

| Long 1 March rocket family | Long March 1 | Small lift expendable launch vehicle | 300 kg (660 lb) | N/A | 1970 | MAI/CASC/CAST | Retired | [118] | ||

| Long March 1D | Small lift expendable launch vehicle | 930 kg (2,050 lb) | N/A | 1995 | CALT | Retired | [119] | |||

| Long March 2 | Long March 2A | Medium lift expendable launch vehicle | 2,000 kg (4,400 lb) | 1974 | CALT | Retired | [120] | |||

| Long March 2C | Medium lift expendable launch vehicle | 3,850 kg (8,490 lb) | 1,250 kg (2,760 lb) | 1,900 kg (4,200 lb) to SSO | 1982 | In service | ||||

| Long March 2D | Medium lift expendable launch vehicle | 3,500 kg (7,700 lb) | 1,300 kg (2,900 lb) to SSO | 1992 | In service | |||||

| Long March 2E | Medium lift expendable launch vehicle | 9,500 kg (20,900 lb) | 3,500 kg (7,700 lb) | 1990 | In service | |||||

| Long March 2F | Medium lift expendable launch vehicle | 8,400 kg (18,500 lb) | 1990 | In service | ||||||

| Long March 3 | Long 3 March | Medium lift expendable launch vehicle | 5,000 kg (11,000 lb) | 1,500 kg (3,300 lb) | 1984 | CALT | Retired | [121] | ||

| Long March 3A | Medium lift expendable launch vehicle | 8,500 kg (18,700 lb) | 2,600 kg (5,700 lb) | 1,600 kg (3,500 lb) to HCO | 1993 | In service | ||||

| Long March 3B, 3B/E | Medium lift expendable launch vehicle | 11,500 kg (25,400 lb) | 5,100 kg (11,200 lb) | 3,300 kg (7,300 lb) to HCO 2,000 kg (4,400 lb) to GEO |

1996 | In service | ||||

| Long March 3C, 3C/E | Medium lift expendable launch vehicle | 3,900 kg (8,600 lb) | 2,400 kg (5,300 lb) to HCO | 2008 | In service | |||||

| Long March 4 | Long March 4A | Medium lift expendable launch vehicle | 4,000 kg (8,800 lb) | 1,500 kg (3,300 lb) to Sun-synchronous orbit | 1988 | CALT | Retired | [122] | ||

| Long March 4B | Medium lift expendable launch vehicle | 4,200 kg (9,300 lb) | 1,500 kg (3,300 lb) | 2,800 kg (6,200 lb) to SSO | 1999 | In service | ||||

| Long March 4C | Medium lift expendable launch vehicle | 4,200 kg (9,300 lb) | 1,500 kg (3,300 lb) | 2,800 kg (6,200 lb) to SSO | 2006 | In service | ||||

| Long March 5 | Heavy lift expendable launch vehicle | 25,000 kg (55,000 lb) (200 km (120 mi) x 400 km (250 mi)) | 14,000 kg (31,000 lb) | 8,200 kg (18,100 lb) to TLI | 2016 | CALT | In service | [123] | ||

| Long March 6 | Small lift expendable launch vehicle | N/A | 1,080 kg (2,380 lb) to 700 km (430 mi) (SSO) | 2015 | CALT | In service | [124] | |||

| Long March 7 | Medium lift expendable launch vehicle | 13,500 kg (29,800 lb) (200 km (120 mi) x 400 km (250 mi)) | 5,500 kg (12,100 lb) | 2016 | CALT | In service | [125] | |||

| Long March 9[126] | Super heavy lift | 140,000[127] | 66,000[128] | 50,000 to TLI[127] 44,000 to TMI[129] |

2028[130]–2030[129] | CALT | In development | |||

| Long March 11 | Small lift expendable launch vehicle | 700 kg (1,500 lb) | 350 kg (770 lb) to 700 km (430 mi) (Sun-synchronous orbit) | 2015 | CALT | In service | [131] | |||

| Mu (rocket family) | Mu-3C | Small lift expendable launch vehicle | 195 kg (430 lb) | 1974 | ISAS/Nissan/IHI | Retired | [132] | |||

| Mu-3H | Small lift expendable launch vehicle | 300 kg (660 lb) | 1977 | Retired | ||||||

| Mu-3S | Small lift expendable launch vehicle | 300 kg (660 lb) | 1980 | Retired | ||||||

| Mu-3SII | Small lift expendable launch vehicle | 770 kg (1,700 lb) | 1985 | Retired | ||||||

| Mu-4S | Small lift expendable launch vehicle | 180 kg (400 lb) | 1971 | Retired | ||||||

| M-V | Small lift expendable launch vehicle | 1,850 kg (4,080 lb) | 1,300 kg (2,900 lb) to Polar LEO | 1997 | Retired | |||||

| N (rocket family) | N-I | Small lift expendable launch vehicle | 1,200 kg (2,600 lb) | 360 kg (790 lb) | 1975 | Mitsubishi Heavy Industries/McDonnell Douglas | Retired | [133] | ||

| N-II | Medium lift expendable launch vehicle | 2,000 kg (4,400 lb) | 730 kg (1,610 lb) | 1981 | Retired | [134] | ||||

| Paektusan-1 | Small lift expendable launch vehicle | 700 kg (1,500 lb) | 1998 | KCST | Retired | [135] | ||||

| Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle | PSLV-G | Medium lift expendable launch vehicle | 3,200 kg (7,100 lb) | 1,050 kg (2,310 lb) | 1,600 kg (3,500 lb) to SSO | 1993 | ISRO | Retired | [136] | |

| PSLV-CA | Medium lift expendable launch vehicle | 2,100 kg (4,600 lb) | 1,100 kg (2,400 lb) to SSO | 2007 | In service | |||||

| PSLV-XL | Medium lift expendable launch vehicle | 3,800 kg (8,400 lb) | 1,300 kg (2,900 lb) | 1,750 kg (3,860 lb) to SSO 1,350 kg (2,980 lb) to TMI |

2008 | In service | ||||

| PSLV-DL | Medium lift expendable launch vehicle | 2,100 kg (4,600 lb) | 1,100 kg (2,400 lb) to SSO | 2019 | In service | |||||

| PSLV-QL | Medium lift expendable launch vehicle | 3,800 kg (8,400 lb) | 1,300 kg (2,900 lb) | 1,750 kg (3,860 lb) to SSO 1,350 kg (2,980 lb) to TMI |

2019 | In service | ||||

| PSLV-3S | Small lift expendable launch vehicle | 500 kg (1,100 lb) (550 km (340 mi) | N/A | Concept only | ||||||

| Qonoos | Medium lift expendable launch vehicle | 3,500 kg (7,700 lb) | 1,500 kg (3,300 lb) | 2025 (Projected) | ISA | Under development | ||||

| Reusable Launch Vehicle | TSTO Reusable launch system | 2016 (Flight experiment) | ISRO | Under development | [137] | |||||

| RPS-420 | Pengorbitan-1 | Small lift expendable launch vehicle | 25 kg (55 lb) | N/A | TBD | LAPAN | Proposed | [138] | ||

| Pengorbitan-2 | Small lift expendable launch vehicle | 50 kg (110 lb) | N/A | TBD | Proposed | |||||

| S-Series (rocket family) | SS-520 | Small lift expendable launch vehicle | 100 kg (220 lb) (>300 km (190 mi) | N/A | 1980 | IHI Corporation | In service | [139] | ||

| Safir | Small lift expendable launch vehicle | 65 kg (143 lb) | N/A | 2008 | ISA | In service | [140] | |||

| Satellite Launch Vehicle | Small lift expendable launch vehicle | 40 kg (88 lb) (400 km (250 mi) | N/A | 1979 | ISRO | Retired | [141] | |||

| Shavit | Small lift expendable launch vehicle | 800 kg (1,800 lb) | N/A | 1988 | Israel Aerospace Industries | In service | [142] | |||

| Simorgh | Small lift expendable launch vehicle | 350 kg (770 lb) | N/A | 2016 (Sub-orbital) | ISA | Under development | [143] | |||

| Small Satellite Launch Vehicle | Small lift expendable launch vehicle | 500 kg (1,100 lb) (500 km (310 mi)) | N/A | 300 kg (660 lb) | 2020 (Planned) | ISRO | Under development | [144] | ||

| TSLV | Small lift expendable launch vehicle | 50 kg (110 lb) (700 km (430 mi)) | N/A | TBD | NSPO | Under development | [145][146] | |||

| Unha | Small lift expendable launch vehicle | 200 kg (440 lb) (465 km (289 mi) x 502 km (312 mi)) | N/A | 2009 | KCST | In service | [147] | |||

| Unified Modular Launch Vehicle | ULV with 6 x S-13 boosters | Medium lift expendable launch vehicle | 4,500 kg (9,900 lb) | 1,500 kg (3,300 lb) | No earlier than 2022 | ISRO | Under development | [89][148][149] | ||

| ULV with 2 x S-60 boosters | Medium lift expendable launch vehicle | 10,000 kg (22,000 lb) | 3,000 kg (6,600 lb) | No earlier than 2022 | Under development | |||||

| ULV with 2 x S-139 boosters | Medium lift expendable launch vehicle | 12,000 kg (26,000 lb) | 4,500 kg (9,900 lb) | No earlier than 2022 | Under development | |||||

| ULV with 2 x S-200 boosters | Medium lift expendable launch vehicle | 15,000 kg (33,000 lb) | 6,000 kg (13,000 lb) | No earlier than 2022 | Under development | |||||

| HLV variant | Heavy lift expendable launch vehicle | 20,000 kg (44,000 lb) | 10,000 kg (22,000 lb) | 2020s | Under development | |||||

| SHLV variant | Super heavy lift expendable launch vehicle | 41,300 kg (91,100 lb)-60,000 kg (130,000 lb) | 16,300 kg (35,900 lb) | 2020s | Under development | |||||

| Uydu Fırlatma Sistemi | Small lift expendable launch vehicle | Microsatellites (700 km (430 mi)) | N/A | TBD | ROKETSAN | Under development | [150] | |||

| Yun Feng SLV | Small lift expendable launch vehicle | 200 kg (440 lb) (500 km (310 mi) | N/A | TBD | NCSIST | Under development | [146] | |||

Orbital Launch Frequency

| 2001[151] | 2002[152] | 2003[153] | 2004[154] | 2005[155] | 2006[156] | 2007[157] | 2008[158] | 2009[159] | 2010[160] | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 5 | 6 | 9 | 11 | 6 | 15 | 73 | |

| 1 | 3 | 3 | – | 2 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 23 | |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 19 | |

| – | 1 | – | 1 | – | – | 1 | – | – | 1 | 4 | |

| – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | 1 | – | 2 | |

| – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | – | 1 | |

| Total | 4 | 10 | 12 | 10 | 8 | 13 | 15 | 16 | 14 | 22 | 124 |

| 2011[161] | 2012[162] | 2013[163] | 2014[164] | 2015[165] | 2016[166] | 2017[167] | 2018[168] | 2019[169] | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19 | 19 | 15 | 16 | 19 | 22 | 18 | 39 | 34 | 201 | |

| 3 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 44 | |

| 3 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 6 | 2 | 35 | |

| 1 | 3 | 1 | – | 1 | – | 1 | – | 3 | 10 | |

| – | 2 | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | – | 3 | |

| – | – | – | 1 | – | 1 | – | – | – | 2 | |

| – | – | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | |

| Total | 26 | 28 | 24 | 26 | 29 | 35 | 31 | 52 | 45 | 296 |

Human Spaceflight

- Legend

- Successful programsPlanned, defined, funded and scheduledPlanned and proposed with no clear deadline or funding or on holdAbandoned or cancelled

| Country | Program | Agency engaged | First orbital crewed launch | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spacecraft | Term(s) for space traveler | First human(s) launched | Date | Launch system | |||

| Project 714 (1968–72) | Chinese space program | Shuguang spacecraft (Intended) | 宇航员 (in Chinese)

yǔhángyuán 航天员 (in Chinese) hángtiānyuán |

N/A | N/A | Long March 2A (Intended) | |

| Project 863 (1976–80) | Chinese space program | Piloted FSW spacecraft (Intended) | N/A | N/A | Long March 2 (Intended) | ||

| HOPE-X (late 1980s–2003) | National Space Development Agency of Japan | HOPE-X spaceplane (Intended) | 宇宙飛行士 (in Japanese)

uchūhikōshi or アストロノート astoronoto |

N/A | N/A | H-IIA (Intended) | |

| ... (1989–2001) | Space Research Center, Baghdad | N/A | رجل فضاء (in Arabic)

rajul faḍāʼ رائد فضاء (in Arabic) rāʼid faḍāʼ ملاح فضائي (in Arabic) mallāḥ faḍāʼiy |

N/A | N/A | Tammouz 2 or 3 (Intended) | |

| Project 921 (1992–present) | China National Space Administration | Shenzhou spacecraft and Tiangong space laboratory | 宇航员 (in Chinese)

yǔhángyuán 航天员 (in Chinese) hángtiānyuán taikonaut("太空人" tàikōng rén) |

杨利伟 (Yang Liwei) | 2003-10-15 | Long March 2F, Long March 3 | |

| Project 869 (1990s) | China National Space Administration | Tianjiao-1 or Chang Cheng-1 (Great Wall-1) winged spaceplanes (Intended) | 宇航员 (in Chinese)

yǔhángyuán 航天员 (in Chinese) hángtiānyuán taikonaut("太空人" tàikōng rén) |

N/A | N/A | 869 reusable shuttle system (Intended) | |

| Kankoh-maru (1993–1997,2005) | Japanese Rocket Society, Kawasaki Heavy Industries and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries | Kankoh-maru reusable shuttle system (Intended) | 宇宙飛行士 (in Japanese)

uchūhikōshi or アストロノート astoronoto |

N/A | N/A | Kankoh-maru reusable shuttle system (Intended) | |

| ... (2001–2003) | National Space Development Agency of Japan | Fuji spacecraft (Intended) | 宇宙飛行士 (in Japanese)

uchūhikōshi or アストロノート astoronoto |

N/A | N/A | H-IIA (Intended) | |

| Project 921-2 (2020–present) | China National Space Administration | X-11 reused spacecraft, Tianzhou non-reentry and Shenzhou Cargo reentry cargo spacecraft and permanent modular Chinese Space Station | 宇航员 (in Chinese)

yǔhángyuán 航天员 (in Chinese) hángtiānyuán taikonaut("太空人" tàikōng rén) |

TBD | TBD | Long March 3, Long March 5 | |

| Indian Human Spaceflight Programme (2007–present) | Human Space Flight Centre (ISRO) | Gaganyaan spacecraft and small space laboratory | Vyomanaut/Gaganaut | TBA | December 2021 (Planned) Before 2022-08-15 (Scheduled) |

GSLV Mk III | |

| Project 921-3 (2000s–present) | China National Space Administration | Shenlong spaceplane | 宇航员 (in Chinese)

yǔhángyuán 航天员 (in Chinese) hángtiānyuán taikonaut("太空人" tàikōng rén) |

TBD | TBD | 921-3 RLV (or Tengyun either HTS maglev launch assist) reusable shuttle system | |

| ... (2008–present) | Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency | HTV-based spacecraft and small space laboratory | 宇宙飛行士 (in Japanese)

uchūhikōshi or アストロノート astoronoto |

TBD | TBD | H-IIB | |

| Iranian human spaceflight program (2005–2017, on hold) | Iranian Space Agency | Class E Kavoshgar spacecraft and small space laboratory | TBD | TBD | TBD | ||

| DPRK space program (2010s-present) | National Aerospace Development Administration | Spacecraft and small space laboratory | TBD | TBD | Unha 9, 20 | ||

China

First human spaceflights

China was the first Asian country and third nation in the world, after the USSR and USA, to send humans into space. During the Space Race between the two superpowers, which culminated with Apollo 11 landing humans on the Moon, Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai decided on 14 July 1967 that China should not be left behind, and initiated their own crewed space program: the top-secret Project 714, which aimed to put two people into space by 1973 with the Shuguang spacecraft. Nineteen PLAAF pilots were selected for this goal in March 1971. The Shuguang-1 spacecraft, to be launched with the CZ-2A rocket, was designed to carry a crew of two. The program was officially cancelled on 13 May 1972 for economic reasons, although the internal politics of the Cultural Revolution likely motivated the closure.

A second, short-lived crewed program was based on the successful implementation of landing technology by FSW satellites. It was announced a few times in 1978 with the publishing of some details, including photos, but then was abruptly canceled in 1980. It has been argued that the second crewed program was created solely for propaganda purposes, and was never intended to produce results.[170]

In 1992, under Project 921-1, authorization and funding was given for the first phase of a third, successful attempt at crewed spaceflight, using a Shenzhou spacecraft. The Shenzhou program included four uncrewed test flights and two crewed missions. The first one was Shenzhou 1 on 20 November 1999. On 9 January 2001, Shenzhou 2 was launched, carrying test animals. Shenzhou 3 and Shenzhou 4 were launched in 2002, carrying test dummies. Following these was the successful Shenzhou 5, China's first crewed mission into space on 15 October 2003, which put Yang Liwei in orbit for 21 hours and made China the third nation to launch a human into orbit.

The second phase of Project 921 started with Shenzhou 7, China's first spacewalk mission. Then, two crewed missions were planned for the first Chinese space laboratory. The PRC initially designed the Shenzhou spacecraft with docking technologies imported from Russia, meaning that it was compatible with the International Space Station (ISS). On 29 September 2011, China launched the Tiangong 1 Space Laboratory. This target module was intended to be the first step in testing the technology required for a planned space station. On 31 October 2011, a Long March 2F rocket carried the Shenzhou 8 uncrewed spacecraft into orbit, which docked twice with the Tiangong 1 module. On 16 June 2012, the Shenzhou 9 craft took off with a crew of three and successfully docked with the Tiangong-1 laboratory on 18 June 2012, at 06:07 UTC, marking China's first crewed spacecraft docking.[171]

Continuing programs

Under Project 921-2, a larger permanent crewed modular Chinese Space Station would constitute the third and last phase of China's LEO human spacefaring. This will have a modular design with an eventual weight of around 60 tons, to be completed sometime before 2020. The first section, designated Tiangong 3, is scheduled for launch after Tiangong 2.[172] The new station will be supported by new X-11 reused crewed, Tianzhou non-reentry and Shenzhou Cargo reentry cargo spacecraft. The first uncrewed flight of X-11 took place on 5 May 2020.

The PRC aims for a human moon landing in the 2030s.

Also, a reusable shuttle system with crewed winged spaceplane orbiter is projected. The first such Tianjiao-1 and Chang Cheng-1 (Great Wall-1) systems were considered in the 1980s–1990s, under Project 869. Now, Project 921-3 plans for a Reusable Launch Vehicle with Shenlong orbiter. As an alternative, the Tengyun two wing-staged reusable shuttle system and HTS maglev launch assist space shuttle were proposed.

India

First human spaceflights

Just a few days after China said that it would put a human into orbit in the second half of 2003, Indian Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee publicly urged his country's scientists to work toward sending a man to the Moon.[173]

India's Human Spaceflight Programme (HSP) was officially started in 2007[174][175] by the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) with the aim of developing the technology needed to launch crewed spacecraft into low Earth orbit.[176] To demonstrate the ability of recovering crewed orbiters, SRE-1 was conducted in the same year.[177] The GSLV Mk III launch system—with the ability to put 10 tonnes in LEO, sufficient to carry crewed spacecraft—was developed, and work on the ISRO Orbital Vehicle initiated. In December 2014, a Crew Module Atmospheric Re-entry Experiment was conducted during the sub-orbital flight of GSLV Mk III.[178]

The Mysore-based Defence Food Research Laboratory (DFRL) has developed dried and packaged food for astronauts. The food laboratory has developed around 70 varieties of dehydrated and processed food items that have undergone strict procedures to zero-in on containing the necessary micro bacterial and macro bacterial nutrients. Special care has to be taken in the packaging. The food item should be of limited weight but at the same time should be high in nutrition.[179]

In July 2018, a pad abort test was conducted to validate a crew escape system.[180] Parachute tests were scheduled before the end of 2019 and multiple in-flight abort tests were planned starting mid-2020.[89]

On 15 August (Indian independence day) 2018, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi declared that before India's 75th independence day in 2022, the country would have sent humans into space. The crewed module mission was renamed Gaganyaan.[181] India is expected to send 3 humans into LEO on Gaganyaan spacecraft for 3–4 days onboard a GSLV Mk III launch vehicle.[182]

Before the prime minister's August 2018 announcement, human spaceflight was not a priority for ISRO, although most of the required capability for it had been realised;[183] afterward it received the highest priority.[184] The Human Space Flight Centre (HSFC) was set up in January 2019 to coordinate implementation of the mission.[185] A third launch pad is under construction at Satish Dhawan Space Centre with the ability to support heavy lift launchers and human spaceflight while the second one is being augmented with similar systems to realise the mission on time. India's crewed orbital vehicle will have two uncrewed flights–at the end of 2020 and mid-2021—before actually taking humans onboard at the end of 2021. Indian astronauts will be dubbed "Vyomanauts"[186] or "Gaganauts". Selected by the Indian Institute of Aerospace Medicine, a team of seven test pilots from the Indian Air Force are undergoing training in Russia per the memorandum of understanding with Glavkosmos, out of which 4 will be ready for India's first human space mission.[89]

As of December 2019, India's Department of Space maintains the scheduled date of December 2021 to conduct human spaceflight.[187]

Continuing programs

India plans to deploy a 20 tonne space station as a follow-up programme to the Gaganyaan mission. On 13 June 2019, ISRO Chief K. Sivan announced the plan, saying that India's space station will be deployed 5–7 years after completion of the Gaganyaan project. He also said that India will not join the International Space Station program. India's space station would be capable of harbouring a crew for 15–20 days at a time. It is expected to be placed in a low Earth orbit of 400 km altitude and be capable of harbouring three humans. Final approval is expected to be given to the program by the Indian government only after the completion of the Gaganyaan mission.[188][189][190]

ISRO is planning to conduct SPADEX (Space Docking Experiment) in 2020 to develop techniques related to orbital rendezvous, docking, formation flying, and remote robotic arm operations, for application to human spaceflight, in-space satellite servicing, and other proximity operations that will be critical for space station operations.[191]

The agency intends to conduct a crewed lunar landing, as well, in future.[192][193]

Japan

Since the late 1980s National Space Development Agency of Japan (NASDA) has developed the HOPE-X small crewed winged spaceplane that would be launched by an H-IIA rocket. Despite having successfully flown sub-scale test prototypes, the project was cancelled in 2003 in favor of participation in the International Space Station with the Kibō Japanese Experiment Module and H-II Transfer Vehicle cargo spacecraft.

As an alternative to HOPE-X, NASDA in 2001 proposed the Fuji crewed capsuled spacecraft for independent or ISS shuttle flights; but the project was not adopted. Since 2008, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency has developed the H-II Transfer Vehicle cargo spacecraft–based crewed spacecraft.

In 1993–1997, the Japanese Rocket Society, Kawasaki Heavy Industries, and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries proposed the Kankoh-maru vertical-takeoff-and-landing single-stage crewed cargo reusable launch system. In 2005, this system was proposed for space tourism.

Iran

Iran expressed for the first time its intention to send a human into space during the summit of Soviet and Iranian Presidents in 1990. Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev reached an agreement in principle with President Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani to make joint Soviet–Iranian crewed flights to the Mir space station; but an agreement was never finalized, due to the subsequent dissolution of USSR.

On 21 November 2005, the Iranian News Agency claimed that Iran has a human space program along with plans for the development of a spacecraft and a space laboratory. [194] On 20 August 2008, the head of the Iran Aerospace Industries Organization (IAIO), Reza Taghipour, revealed that Iran intends to launch a human mission into space within a decade. This goal was described as the country's top priority for the next 10 years, in order to make Iran the leading space power of the region by 2021.[195][196]

In August 2010, President Ahmadinejad announced that Iran's first astronaut should be sent into space onboard an Iranian spacecraft by no later than 2019.[197][198] A sub-orbital spaceflight was conducted in 2016.[199]

On 17 February 2015, Iran unveiled a mock prototype of an Iranian crewed spacecraft that would be capable of taking one astronaut into space.[200] According to Iran's space administrator, this program was indefinitely put on hold in 2017.[201]

According to unofficial Chinese internet sources, an Iranian participation in the future Chinese space station program has been under discussion.[202] Currently, Iran doesn't have a medium-lift rocket similar to the Long March 2F, GSLV Mk III, or H-IIA, presently making Iran's sending a human into space unlikely.[203]

Iraq

According to a 5 December 1989 press release from the Iraqi News Agency, about the first (and last) test of the Tammouz space launcher, Iraq intended to develop crewed space facilities by the end of the 20th century. These plans were put to an end by the Gulf War of 1991 and the hard economic times that followed.

Solar System exploration

Solar System exploration and human spaceflights are major space technologies in the public eye. Since Sakigake, the first interplanetary probe from Asia, was launched in 1985, Japan has completed the most planetary explorations, but other nations are catching up.

Moon race

The Moon is thought to be rich in Helium-3, which could one day be used in nuclear fusion power plants, to meet future energy demands in Asia. All three main Asian space powers plan to send people to the Moon in the distant future and have already sent lunar probes.

| Asian lunar exploration probes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mission name | Type | Year | Vehicle | Outcome | |

(MUSES-A) |

Flyby/Orbiter | 1990 | Success | ||

| Orbiter | Failure | ||||

| Orbiter | 2004 (intended) Never launched |

Cancelled and integrated into Russia's Luna-Glob. | |||

(VRAD) |

Orbiter | 2007 | Success | ||

| Orbiter | 2007 | Success | |||

| Orbiter | 2008 | Success | |||

| Orbiter | 2010 | Success | |||

| Orbiter Lander Rover |

2013 | Success | |||

| Flyby | 2014 | Success | |||

| Orbiters Lander Rover |

2018–19 | Success | |||

| Orbiter Lander Rover |

2019 | Partial success | |||

| Sample return | 2020 | Success | |||

| Lander Rover |

Q2 2021 | Planned | |||

| Orbiter Lander Rover |

2020s (intended) | Cancelled | |||

| Lander | January 2022 | Planned | |||

| Orbiter | August 2022 | Planned | |||

| Flyby | 2022 | Planned | |||

| Sample return | 2023–24 | Planned | |||

| Lander | 2023 | TBD | Planned | ||

| Orbiter Lander Rover |

2024 | Proposed | |||

| Lander | 2026 | TBD | Proposed | ||

| TBD | 2026 | Proposed | |||

Probing the Moon

Japan was the first Asian country to launch a lunar probe. The Hiten (Japanese: "flying angel") spacecraft (known before the launch as MUSES-A), built by the Institute of Space and Astronautical Science of Japan, was launched on 24 January 1990. In many ways, the mission did not go as was planned. Kaguya, the second Japanese lunar orbiter spacecraft, was launched on 14 September 2007.

China launched its first lunar probe, Chang'e-1, on 24 October 2007; the probe successfully entered lunar orbit on 5 November 2007.

India launched its first lunar probe, Chandrayaan-1, on 22 October 2008; the probe successfully entered its final lunar orbit on 2 November 2008. The mission was considered a major success, and the probe detected water on the lunar surface.

Moon landings

The first confirmed Moon landing from Asia was Hiten's mission in 1993. Before an intentional hard landing at the end of the mission, some pictures of the lunar surface were taken before impact.[204] Hiten was not designed as a Moon lander and had few scientific instruments for lunar exploration. The next Japanese Moon-landing program was the LUNAR-A, in development since 1992. Although the LUNAR-A orbiter was cancelled, its penetrators were integrated into the Russian Luna-Glob program, which was scheduled to launch in 2011. The penetrators are "relatively" hard landers,[205] but they are not expected to be destroyed on impact.

The next Asian probe to land on the Moon was the Indian Moon Impact Probe (MIP), which was released from the Chandrayaan-1 spacecraft in 2008. MIP was a hard lander and was designed to displace the ground under it for analysis. MIP was designed to be destroyed at impact, but its instruments performed lunar observations to within 25 minutes before impact. The lessons learned from this landing were to be applied to future soft landings on spacecraft, such as Chandrayaan-2, which crashed, following successful orbital insertion, and was only a limited success. After the accomplishment of its first human mission, India has proposed space stations and manned missions to the Moon.[192][206]

The Chinese Chang'e-1 spacecraft also achieved a\ hard landing at the end of its mission in 2009, when China became the sixth country to reach the lunar surface. One purpose of the lander was to pre-test for future soft landings. A Chinese lunar soft landing was achieved with the Chang'e-3 mission. With the Chang'e 4, China became the first country to land on the far side of the Moon. China also aims to undertake a human Moon landing by the late 2020s.[207]

Exploration of the major planets

Japanese interplanetary probes have been mostly limited to Small Solar System bodies, such as comets and asteroids. Japan was the world's first country to launch a spacecraft to the asteroids. JAXA's Nozomi probe was launched in 1998, but contact with the probe was lost due to electrical failures before visiting the planet Mars. The second Japanese probe, Akatsuki, was launched in 2010, bound for the planet Venus. Akatsuki entered orbit around Venus on 7 December 2015. Together with the European Space Agency, JAXA has launched Mio spacecraft for mapping the magnetic field of Mercury. The spacecraft will also conduct a flyby of Venus.

Chinese scientists expect that China will take 20 years to launch independent planetary probes.[208] The Chinese human Mars exploration program is planned by the Chinese Academy of Sciences for around 2050.[209] After the failed attempt to launch Yinghuo-1, China is planning another Mars mission, with an orbiter as well as a rover, alongside its plans to send an orbiter to Venus around 2025.[210] China has also been planning to send an orbiter to Jupiter.

India successfully launched its Mars Orbiter Mission on 5 November 2013. It reached Mars in September 2014. India has become the only country to successfully insert a satellite into Martian orbit on its maiden attempt; and, as such, it also became the first Asian country to achieve this feat. India is planning another mission to Mars in the 2020s.[211] India was scheduled to launch Aditya-L1 near the Sun to study Solar corona[212] and is developing the Shukrayaan-1 spacecraft to be sent to Venus.[213] India is also studying exploration missions to asteroids, Jupiter, to beyond the solar system like the American Voyager 1 and to exo-planets.[214]

| Asian interplanetary exploration probes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mission name | Destination | Type | Year | Vehicle | Outcome |

| Mars | Orbiter | 2003 | Failure | ||

| Asteroid: 25143 Itokawa | Sample return | 2005-7 | Success | ||

(PLANET-C) |

Venus | Orbiter | 2010 | Failure (Failed orbiter insertion) | |

| 2015 | Success | ||||

| Venus | Flyby | 2010 | Success | ||

| Venus | Flyby | 2010 | Failure | ||

| Mars | Orbiter | 2011 | Failure | ||

| Asteroid: 4179 Toutatis | Flyby | 2012 | Success | ||

| Mars | Orbiter | 2013–14 | Success | ||

| Asteroid: 162173 Ryugu | Sample return | 2014–20 | Success | ||

| Asteroid: 2000 DP107 | Flyby | 2016 | Failure | ||

| Mercury | Orbiter | 2018–24 | en route | ||

| Mars | Orbiter/Rover | 2020–21 | en route | ||

| Mars | Orbiter | 2020–21 | en route | ||

| Sun | Orbiter | 2020 | Planned | ||

| Asteroid: 3200 Phaethon | Flyby | 2022–26 | Planned | ||

| Venus | Orbiter and aerobots | 2023 | Planned | ||

| Mars | Orbiter | 2024–2025 | TBD | Planned | |

| Phobos | Sample return | Planned | |||

| Mars | Orbiter Lander Rover |

TBD | Planned | ||

Budgets

| Agency | Country | Budget (in millions of US $) |

Year | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| China National Space Administration | 11000 | 2018 | [215] | |

| Indian Space Research Organisation | 1760 | 2020 | [216] | |

| Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency | 1710 | 2017 | [217] | |

| Korean Aerospace Research Institute | 583 | 2016 | [218] | |

| Iranian Space Agency and Iranian Space Research Center | 393 | 2018 | [219] | |

| National Institute of Aeronautics and Space | 55 | 2019 | [220][221] | |

| Space and Upper Atmosphere Research Commission | 43 | 2019 | [222] | |

| Philippine Space Agency | 38 | 2019 | [223] | |

| Israel Space Agency | 14.5 | 2019 | [224] | |

| Turkish Space Agency | 4.3 | 2019 | [225] |

Notes and references

- Hennock, Mary. "Asia's Space Race Between China and India". Newsweek.com. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- "Shooting for the moon: The new space race". CNN. 10 October 2007.

- Blume, Claudia (17 May 2007). "Asia Nations Gaining Ground in Space Race". www.globalsecurity.org. Hong Kong.

- "SPARRSO". sparrso.gov.bd. Archived from the original on 11 March 2008. Retrieved 7 March 2008.

- "China National Space Administration – Organization and Function". cnsa.gov.cn. Archived from the original on 28 February 2008. Retrieved 9 March 2008.

- "About ISRO". isro.org. Archived from the original on 13 October 1999.

- "About ISRO". isro.gov.in. Indian Space Research Organization. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- "All Missions". isro.gov.in. Indian Space Research Organization. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- "Realtime Business News, Economic News, Breaking News and Forex News". RTTNews.

- "Iran tests sounding rocket, unveils first homemade satellite | World | RIA Novosti". rian.ru. En.rian.ru. 28 October 2005. Retrieved 13 June 2011.

- "Iran launches homegrown satellite". BBC News. 3 February 2009.

- "JAXA HISTORY". jaxa.jp. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- ライフサイエンス研究. jaxa.jp (in Japanese). JAXA. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- "Background". Malaysian National Space Agency, Official Website. angkasa.gov.my. Archived from the original on 7 March 2008.

- "朝鲜宣布发展太空计划抗衡"西方强权"". minzuwang.com. 民族网. 8 February 2009. Retrieved 26 February 2009.

- "Despite Clinton, Korea has rights". workers.org. Workers.org. 25 February 2009. Retrieved 13 June 2011.

- N. Korea's launch causes worries about nukes, Iran and the Pacific

- Parrocha, Azer (13 August 2019). "Duterte signs law creating Philippine Space Agency". Philippine News Agency. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- Previously named National Space Program Organisation, until 1 April 2005 – "About NSPO/Heritage". nspo.org.tw. Archived from the original on 10 August 2007. Retrieved 1 April 2009.

- "Geo-Informatics and Space Technology Development Agency – About Us". gistda.or.th. Archived from the original on 18 October 2011. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- "China puts its first man in space". BBC News. 15 October 2003. Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- "Gaganyaan: Rs 10,000 crore plan to send 3 Indians to space by 2022 | India News – Times of India". Timesofindia.indiatimes.com. 29 December 2018. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- "Asia could win next 'Space Race', US scientists fear".

- "China Denies There's an Asian Space Race". Fox News. 1 November 2007. Archived from the original on 20 February 2009. Retrieved 29 February 2008.

- "Concern over China's missile test". BBC News. 19 January 2007. Retrieved 1 January 2010. BBC News

- "Shooting down satellite raises concerns about military space race".

- https://themirk.com/india-enters-the-elite-club-successfully-shot-down-low-orbit-satellite

- "Heated Space Race Under Way in Asia". ABC News

- Leonard David Space.com

- "Programming glitch, not radiation or satellites, doomed Phobos-Grunt". 7 February 2012. Archived from the original on 10 February 2012. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- "China's man in space gets mixed reaction".

- "The dawn of a new space race?". BBC News. 14 October 2005. Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- "Transported on a Bicycle, Launched from a Church: The Amazing Story of India's First Rocket Launch". The Better India. 8 November 2016. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- "India Limbers Up for Space Race As Prime Minister Asks for the Moon". Archived from the original on 2 February 2003.

- "Rakesh Sharma – First Indian in Space". AeroSpaceGuide.net. 15 February 2017. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- "India 'on course' for the Moon". BBC News. 4 April 2003. Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- "India and US to explore the Moon". BBC News. 9 May 2006. Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- "What is Chandrayaan-2?".

- "ISRO Completes "Scaled-Down" Test For Safe Landing Of Chandrayaan-2".

- "BTVI – India's Maiden Mars Mission Makes History". Btvin.com. 24 September 2014. Archived from the original on 13 April 2016. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- "PSLV puts 20 satellites in orbit". The Hindu. 22 June 2016. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- Barry, Ellen (15 February 2017). "India Launches 104 Satellites From a Single Rocket, Ramping Up a Space Race". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- "India Launches More Than 100 Satellites into Orbit". Time. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 15 February 2017.