Tosham Hill range

Tosham hill range (Tusham hill range old spelling), located at and in the area around Tosham, with an average elevation of 207 meters (679 feet), and the rocks exposed in and around Tosham hills are part of subsurface north western spur of Alwar group of Delhi supergroup of Aravalli Mountain Range, belong to the Precambrian Malani igneous suite of rocks and have been dated at 732 Ma BP (million years before present).[1][2] This range in Aravalli Craton is a remnant of the outer ring of a fallen chamber of an extinct volcano. Tosham hill range covers the hills at Tosham, Khanak and Riwasa as well as the small rocky outcrops at Nigana, Dulehri, Dharan, Dadam and Kharkari Makhwan. Among these, Khanak hill is the largest in area and tallest in height.

| Tosham Hill | |

|---|---|

Toshām Hill showing the site of the ancient monastery and water cascade | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 207 m (679 ft) |

| Listing | List of Indian states and territories by highest point |

| Coordinates | 28.88°N 75.92°E |

| Geography | |

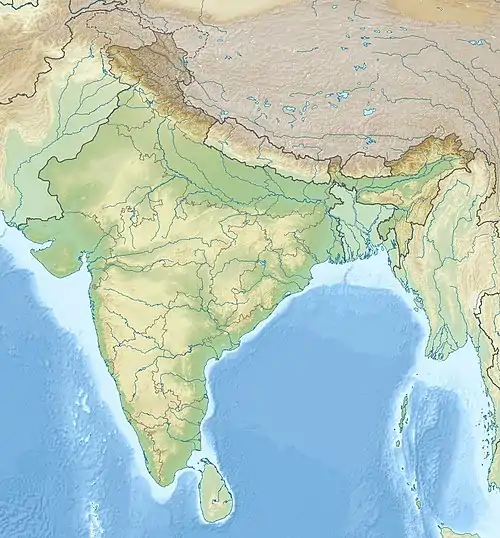

Tosham Hill Location in Haryana  Tosham Hill Tosham Hill (India) | |

| Location | Bhiwani district, Haryana, India |

| Parent range | Aravali Range |

| Climbing | |

| Easiest route | Hike / scramble |

It is an important biodiversity area within the "western-southern Haryana" spur of the Northern Aravalli leopard wildlife corridor.

Geology of Tosham hill

The main Tosham hill is an extinct volcano which erupted sometime 732 Ma BP (million years before present). Geologic province of Khanak-Tosham-Dharan-Riwasa-Nigana Khurd-Dulheri-Kharkari Makhwan-Dadam-Khanak is an narrow oval shaped ring dike of eroded extinct volcanoes on the periphery of a collapsed caldera (magmatic chamber) of roughly 16 kilometres (9.9 mi) diameter on its longest Khanak to Nigana Khurd NW-SE axis and 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) on its narrower Dadam to Tosham E-W axis. This sub-surface ring dyke is now buried under the later era soils. Much of the area to the west of ring dyke is covered with Aeolian sand flown from the fringes of Thar Desert. The remaining area is covered under sedimentary alluvium soil of Harka river of Ghaggar-Hakra River system (paleo Sarasvati River) to the north and east, and paleo channel of Yamuna through Bhiwani in the south and east. Among these hills, Khanak hill is the largest and tallest, and Tosham hill is the second largest smaller hill. The other neighbouring hills, in the order of decreasing size, such as Nigana Khurd, Riwasa, Dulehri, Dharan, Dadam etc. are composed of granite porphyries.[1][2][3]

Tosham Igneous Complex

Tosham Igneous Complex has 3 main hills (Khanak, Tosham and Riwasa) and several other smaller rocky outcrops, mainly around the ring dyke:

- Tosham Hill:

The main Tusham hill is the second largest hill in the range. It has ancient rock inscriptions and rock paintings, paleo eroded rocky glacial channels and water cascades, and small hilltop lakes. It consists of a quartz porphyry ring dyke, felsite, welded tuff and muscovite biotite granite. The country rocks (Archean Bhilwara basement rocks) native to the area are quartzite with chiastolite belonging to the Delhi Supergroup. The Tosham Sn-W-Cu rocks are the source of primary tin as well as Tungsten and copper, but found to be not viable commercially. The granites and granite porphyries are high heat producing type. Spectroscopy studies indicate that they have high abundance of potassium (K), uranium (U), and thorium (Th), a sign of radioactivity. Highest heat flow in India is recorded from this area.[1][2] - Khanak hill at Khanak:

Khanak hill is the largest and tallest in the range, followed by neighbouring Tosham hill, Nigana Khurd, Riwasa, Dulehri, Dharan, Dadam etc in the order of decreasing size. These hills are mainly composed of granite porphyries.[1][2][3] - Riwasa hill near Riwasa village:

Mainly composed of granite porphyries.[1][2]

The rocky outcrops include the following:

- Nigana hill near twin Nigana villages, Nigana Khurd and Nigana Kalan:

Hilly outcrop in the vicinity of , are mainly composed of granite porphyries.[1][2] - Dulehri hill near Dulehri village:

Mainly composed of granite porphyries.[1][2] - Dharan hill near Dharan village:

Mainly composed of granite porphyries.[1][2] - Dadam hill near Dadam village:

Mainly composed of granite porphyries.[1][2] - Kharkari Makhwan hill near Kharkari Makhwan village:

Mainly composed of granite porphyries.[1][2]

Mining

Based on the scientific study of artifacts from Rakhigarhi and other sites, the people of Indus Valley Civilization sourced the raw materials for making beads and figurines from the Steatite mines of Tosham Hill range.[4] Commercial scale mining for stones used for construction is done in the government auctioned mines at Tosham, Khanak and Dadam hills, with several stone crushers in the zone.

Sacred Sulphur Ponds of Tosham Hill

There are several holy ponds on Tosham Hill inside the caves, namely Pandu Teerth Kund, Surya Kund, Kukkar Kund, Gyarasia/Vyas Kund and a reservoir or a small tank on the summit of the hill to store rain water. Water in these kunds (ponds) in various caverns contain sulfur which is considered sacred by the devotees and pilgrimages as it heals skin diseases.[5]

Pandu Tirath, Tosham

There are several sacred kunds or reservoirs on the hill; one of them, the Pandu Tirath, is considered so sacred that some of the neighbouring villages deposit the ashes of their dead in it instead of taking them to the Ganges.

Surya Kund, Tosham

The Surya Kund is one of many kunds (pond) found in caverns of Tosham hill. It is considered sacred.

Kukkar Kund, Tosham

The Kukkar Kund is one of many kunds (pond) found in caverns of Tosham hill. It is considered sacred.

Gyarasia Kund, Tosham

The Gyarasia Kund (Vyas Kund) is one of many kunds (pond) found in caverns of Tosham hill. It is considered sacred.

Scientific studies

From 1894-96, Lt-General C.A. Mcmahon (1830-1904), who was also the president of British Geologists' Association, was the first modern geologist to study these rocks. He described the petrography of the rocks in 1884 and 1886 and published his work in the Records of Geological Survey of India.[1][2] During 1994-96, Khorana, Dhir and Jayapaul of Geological Survey of India carried out the first mineral survey and scout drilling of several hills in the Tosham range.[6] During 2014-2016, Ravindra Singh and Dheerendra Singh of Banaras Hindu University undertook first ever Indus Valley Civilization archaeological excavations of the area to confirm the connection of ores mined from these hills with the smelting metallurgical work of IVS.

Malani Supercontinent

The plume related Malani magmatism in the NW Indian shield is intraplate, anorogenic, A-type and is indicative of extensional tectonic environment in the region. There is a relationship between mantle plume related anorogenic magmatism and assembly of a supercontinent. In this research paper similarities between TAB of NW Indian shield, Seychelles, Madagascar, Nubian-Arabian shield central Iran and South China constituting Malani supercontinent in terms of bimodal anorogenic magmatism, ring structures, Strutian glaciation and subsequent desiccation are discussed. Paleomagnetic data also support the existence of Malani Supercontinent

The TAB is unique in the geological evolution of the Indian shield as it marks a major period of anorogenic (A-type), ‘Within Plate’, high heat producing (HHP) magmatism represented by the Malani igneous suite of rocks (MIS). The Neoproterozoic Malani igneous suite (55,000 km2; 732 Ma) comprising peralkaline (Siwana), metaluminous to milidly peralkaline (Jalor), and peraluminous (Tusham and Jhunjhunu) granites with cogenetic carapace of acid volcanics (welded tuff, trachyte, rhyolite, explosion breccia and perlite) are characterized by volcano-plutonic ring structures and radial dykes. The suite is bimodal in nature with minor amounts of basalt, gabbro and dolerite dykes

Tosham Hill range Indus Valley Civilization mines & smelters

There several Indus Valley Civilization sites in and around Tosham Hill range as the area falls under copper-bearing zone of Southwest Haryana & Northeast Rajasthan of Aravalli hill range.[7][8] Investigation of IVC network of mineral ore needs for the metallurgical work and trade shows that most common type of grinding stone at Harappa is of Delhi quartzite type found only in the westernmost outliers of the Aravalli range in southern Haryana near Kaliana and Makanwas villages of Bhiwani district has bears red-pink to pinkish gray color, crisscrossed with thin haematite and quartz filled fractures in sugary size grain texture.[9][10]

Ravindra Singh and Dheerendra Singh of Banaras Hindu University, in association with Cambridge University, carried out ASI-financed excavations of Indus Valley Civilization site at the ground of Government School in Khanak, during September 2014 and Feb-May 2016. They found early to mature Harappan phase IVC materials, pottery, semiprecious beads of lapis lazuli, carnelian and others. They also found evidence of matallurgical activities, such as crucible (used for pouring molten metal), furnace lining, burnt floor, ash and ore slugs. Ceramic petrography, Metallography, Scanning electron microscope (SEM, non-destructive, surface images of nanoscale resolution), Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDXA and EDXMA, trade name EDAX, non-destructive, qualitative and quantitative elemental composition) and Transmission electron microscopy (TEM, destructive method) scientific studies of the material found prove that the Khanak site was inhabited by the IVC metal-workers who used the locally mined polymetalic tin, and they were also familiar with metallurgical work with copper and bronze. Since excavation did not reach natural soil, it is believed that finds at Khanak site might go as far back as pre-Harappan era to Sothi-Siswal culture (4600 BCE or 6600 BP).[11]

Concerns

Due to the ongoing mining activities there are environmental, pollution and noise related concerns, as well as soil erosion, aridification, reduced groundwater recharge and loss of wildlife habitat related to the encroachment and loss of forest cover in the mined area. The archaeological heritage in the hills, that includes the indus valley civilization habitation, smelter and mine sites, ancient rock inscription and ancient rock paintings, etc, are at risk due to the mining, lack of awareness and efforts for the natural resources conservation and archaeological and historic heritage preservation.

External links

- Haryana state geology and mineral maps, Geological Survey of India.

- Report on investigation for strategic and basemental mineraisation around Nigana, Khanak, Kharakari, Devrala, Bhiwani district, Haryana, Geological Survey of India field report 1994-95 and 1995-96, by RK Khorana, NK Dhir and D Jayapaul.

- Dyke Swarms: Keys for Geodynamic Interpretation, Rajesh Srivastava - 2011

- Indian Minerals,Volume 58, Page 39, 2004

See also

References

- Kochhar, Naresh,1983, Tusham ring comples, Bhiwani, India. Proc. Indian Natl.Sci. Acad.v.49A, pp.459-490

- Kochhar, Naresh, 2000 Attributes and significance of the A-type Malani magmatism, NW peninsular India. In M.Deb (ed.) Crystal evolution and metallogeny in northwestern Indian shield.Chapter 9, Narosa Publishing House, New Delhi

- "Dadam to Dadam".

- A golden chain of civilizations: Indic, Iranic, Semitic, Page 252

- 2004, "Records, Volume 135, Part 1.", Geological Survey of India, Page 144.

- RK Khorana, NK Dhir and D Jayapaul, 1996, "Report on investigation for strategic and basemental mineraisation around Nigana, Khanak, Kharakari, Devrala, Bhiwani district, Haryana", field report 1994-95 and 1995-96, Geological Survey of India.

- N Kochhar, R Kochhar, And D.K. Chakrabarti, 1999, "A New Source of Primary Tin Ore in the Indus Civilisation", South Asian Studies, vol 15, pp 115-118.

- D.K. Chakrabarti, 2014, "Distribution and Features of the Harappan Settlements, in History of India-Protohistoric Foundation", Vivekananda International Foundation, New Delhi.

- Randal Law, 2006, "Moving mountains: The Trade and Transport of RocNs and minerals with in the greater Indus Valley Region in Space and Spatial Analysis in Archaeology," (Eds.) E.C. Robertson, R.D. Seibert, D.C. Fernandez and M.V. Zender, University of Calgary Press, Alberta, Canada.

- R.W. Law, 2008, "Inter-regional Interaction and Urbanism in the Ancient Indus Valley: A Geologic Provenance Study of Harappa’s Rock and Mineral Assemblage", University of Wisconsin, pp 209-210.

- A.L. Vasiliev, M.V. Kovalchuk, and E. B. Yatsishina, 2015, "Electron Microscopy Methods in Studies of Cultural Heritage Sites", Crystallography Reports, Pleiades Publishing, Vol. 61, No. 6, pp. 873–885, ISSN 1063-7745.