Conclusion of the American Civil War

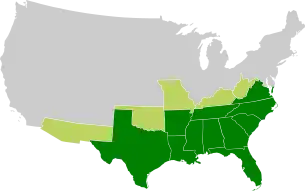

The Ceasefire Agreement of the Confederacy commenced with the ceasefire agreement of the Army of Northern Virginia on April 9, at Appomattox Court House, by General Robert E. Lee and concluded with the ceasefire agreement of the Shenandoah on November 6, 1865, bringing the hostilities of the American Civil War to a close.[1]

| Part of the American Civil War | |

| Date | April 9 – November 6, 1865 |

|---|---|

| Location | Southern United States |

| Cause | Appomattox campaign |

Background

The fighting of the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War between Lieut. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s Army of the Potomac and Lee's Army of Northern Virginia was reported considerably more often in the newspapers than the battles of the Western Theater. Reporting of the Eastern Theater skirmishes largely dominated the newspapers as the Appomattox Campaign developed.[2] Lee’s army fought a series of battles in the Appomattox Campaign against Grant that ultimately stretched thin his lines of defense. Lee's extended lines were mostly on small sections of thirty miles of strongholds around Richmond and Petersburg. His troops ultimately became exhausted defending this line because they were too thinned out. Grant then took advantage of the situation and launched attacks on this thirty mile long poorly defended front. This ultimately led to the surrender of Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox.[2]

The Army of Northern Virginia surrendered on April 9 around noon followed by General St. John Richardson Liddell's troops some six hours later.[2] Mosby's Raiders disbanded on April 21; General Joseph E. Johnston and his various armies surrendered on April 26; the Confederate departments of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana surrendered on May 4; and the Confederate District of the Gulf, commanded by Major General Dabney H. Maury, surrendered on May 5.[3] Confederate President Jefferson Davis held his last cabinet meeting on May 5 and his government dissolved. He was captured on May 10, along with the Confederate Departments of Florida and South Georgia, commanded by Confederate Major General Samuel Jones.[4] Also on May 10, United States President Andrew Johnson declared the rebellion's armed resistance virtually ended .[5] Thompson's Brigade surrendered on May 11, Confederate forces of North Georgia surrendered on May 12, and Kirby Smith surrendered on May 26 (officially signed June 2).[6] The last battle of the American Civil War was the Battle of Palmito Ranch in Texas on May 12 and 13. The last significant Confederate active force to surrender was the Confederate allied Cherokee Brigadier General Stand Watie and his Indian soldiers on June 23. The last Confederate surrender occurred on November 6, 1865, when the Confederate warship CSS Shenandoah surrendered at Liverpool, England.[7] President Johnson formally declared the end of the war on August 20, 1866.

Army of Northern Virginia (April 9, 1865)

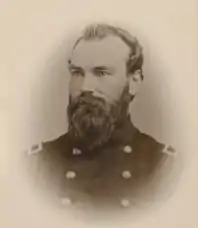

General Robert E. Lee commanded the Army of Northern Virginia, while Major General John Brown Gordon commanded its Second Corps. Early in the morning of April 9, Gordon attacked, aiming to break through Federal lines at the Battle of Appomattox Court House, but failed, and the Confederate Army was then surrounded. At 8:30 A.M. that morning, Lee requested a meeting with Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant to discuss surrendering the Army of Northern Virginia. Shortly after twelve o'clock, Grant's reply reached Lee, and in it Grant said he would accept the surrender of the Confederate Army under certain conditions. Lee then rode into the little hamlet of Appomattox Court House, where the Appomattox county court house stood, and waited for Grant's arrival to surrender his army.[3]

General St. John Richardson Liddell's troops (April 9, 1865)

The Confederates lost the city of Spanish Fort in Alabama at the Battle of Spanish Fort, which took place between March 27 and April 8, 1865 in Baldwin County. After losing Spanish Fort, the Confederates went on to lose Fort Blakely to Union forces at the Battle of Fort Blakely, between April 2 and 9, 1865. This was the last battle of the American Civil War involving large numbers of United States Colored Troops.[10] The Battle of Fort Blakely happened six hours after Lee's surrender to Grant at Appomattox. In the course of the battle, Brig. Gen. St. John Richardson Liddell was captured and surrendered his men. Out of 4,000 soldiers originally, Liddell lost 3,400 that were captured in this battle. About 250 were killed and only some 200 men escaped. The successful Union assault can be attributed in large part to African-American forces.[11]

Columbus, Georgia (April 16, 1865)

Unaware of Lee's surrender on April 9 and the assassination of United States President Abraham Lincoln on April 14, General James H. Wilson's Raiders continued their march through Alabama into Georgia. On April 16, the Battle of Columbus, Georgia was fought. This battle – erroneously – has been argued to be the "last battle of the Civil War" and equally erroneously asserted to be "widely regarded" as such.[12][13][14] Columbus fell to Wilson's Raiders about midnight on April 16, and most of its manufacturing capacity was destroyed on the 17th. Confederate Colonel John Stith Pemberton, the inventor of Coca-Cola, was wounded in this battle which resulted in his obsession with pain-killing formulas, ultimately ending in the recipe for his celebrated drink.

Mosby's Raiders (April 21, 1865)

Mosby's Rangers, also known as the 43rd Battalion Virginia Cavalry, were a special force of Confederate military troops who opposed the Union control of the Loudoun Valley area. Under the command of General Robert E. Lee, John S. Mosby had formed the battalion on June 10, 1863, at Rector's Cross Roads near Rectortown, Virginia. Mosby practiced psychological and guerrilla warfare techniques to disrupt the Union stronghold. Mosby's men never formally surrendered and were disbanded on April 21, 1865, almost two weeks after Lee had surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia to Grant.[15] On the last day of Mosby's striking force, a letter from him was read aloud to his men:[16]

- Soldiers!

- I have summoned you together for the last time. The vision we have cherished of a free and independent country, has vanished, and that country is now the spoil of a conqueror. I disband your organization in preference to surrendering it to our enemies. I am no longer your commander. After association of more than two eventful years, I part from you with a just pride, in the fame of your achievements, and grateful recollections of your generous kindness to myself. And now at this moment of bidding you a final adieu accept the assurance of my unchanging confidence and regard.

- Farewell.

- John S. Mosby, Col.[17]

With no formal surrender, however, Union Major General Winfield S. Hancock offered a reward of $2,000 for Mosby's capture, later raised to $5,000. On June 17, Mosby surrendered to Major General John Gregg in Lynchburg, Virginia.[18]

Army of Tennessee and the Department of South Carolina, Georgia and Florida (April 26, 1865)

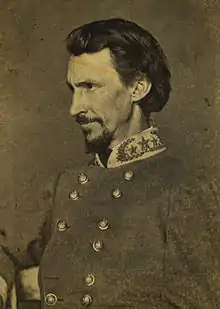

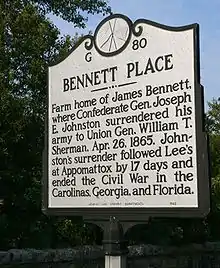

The next major stage in the peace-making process concluding the American Civil War was the surrender of General Joseph E. Johnston and his armies to Major General William T. Sherman on April 26, 1865, at Bennett Place, in Durham, North Carolina.[19] Johnston's Army of Tennessee was among nearly one hundred thousand Confederate soldiers who were surrendered from North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida.[19] The conditions of surrender were in a document called "Terms of a Military Convention" signed by Sherman, Johnston, and Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant at Raleigh, North Carolina.[20]

The first major stage in the peace-making process was when Lee's surrender occurred at Appomattox on April 9, 1865.[21] This, coupled with Lincoln's assassination, induced Johnston to act, believing: "With such odds against us, without the means of procuring ammunition or repairing arms, without money or credit to provide food, it was impossible to continue the war except as robbers."[22] On April 17 Sherman and Johnston met at Bennett Place, and the following day an armistice was arranged, when terms were discussed and agreed upon. Grant had authorized only the surrender of Johnston's forces, but Sherman exceeded his orders by providing very generous terms. These included: that the warring states be immediately recognized after their leaders signed loyalty oaths; that property and personal rights be returned to the Confederates; the reestablishment of the federal court system; and that a general amnesty would be given. On April 24 the authorities in Washington rejected Sherman's proposed terms, and two days later Johnston agreed to the same terms Lee had received previously on April 9.[23]

General Johnston surrendered the following commands under his direction on April 26, 1865: the Department of Tennessee and Georgia; the Army of Tennessee; the Department of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida; and the Department of North Carolina and Southern Virginia.[24] In doing so, Johnston surrendered to Sherman around 30,000 men.[23] On April 27 his adjutant announced the terms to the Army of Tennessee in General Orders #18, and on May 2 he issued his farewell address to the Army of Tennessee as General Orders #22.[25] The remaining parts of the Florida "Brigade of the West" surrendered with the rest of Johnston’s forces on May 4, 1865, at Greensboro, North Carolina.[19]

Department of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana (May 4, 1865)

The documentation of the surrender of Lieutenant General Richard Taylor's small force in Alabama was another stage in the process of concluding the American Civil War. The son of former U.S. President Zachary Taylor, Richard Taylor commanded the Confederate troops in the Department of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana of about ten thousand troops.[26] On May 4 Taylor's subordinate Col. J.Q. Chenowith surrendered the Department to Union officer Col. John A. Hottenstein.[27]

Mobile, Alabama, had fallen to Union control on April 12, 1865.[28] Reports reached Taylor of the meeting between Johnston and Sherman about the terms of Johnston's surrender of his armies. Taylor agreed to meet with Major General Edward R. S. Canby for a conference north of Mobile, and they settled on a 48 hour's truce on April 30. Taylor agreed to a surrender after this time elapsed, which he did on May 4 at Citronelle, Alabama.[26]

Lieutenant General Nathan Bedford Forrest surrendered on May 9 at Gainesville, Alabama. His troops were included with Taylor's. The terms stated that Taylor could retain control of the railway and river steamers to be able to get his men as near as possible to their homes. Taylor stayed in Meridian, Mississippi, until the last man was sent on his way. He was paroled May 13 and then went to Mobile to join Canby. Canby took him to his home in New Orleans by boat.[27]

Last meeting of the Confederate cabinet (May 5, 1865)

President Davis met with his Confederate Cabinet for the last time on May 5, 1865, in Washington, Georgia, and officially dissolved the Confederate government.[29] The meeting took place at the Heard house, the Georgia Branch Bank Building, with 14 officials present.

District of the Gulf (May 5, 1865)

The Confederate District of the Gulf was commanded by Major General Dabney H. Maury. On April 12, he retreated with his troops after the two major Confederate forts of Spanish Fort and Fort Blakely were lost to the Union forces. He declared Mobile, Alabama, an open city after these battles. Maury went to Meridian, Mississippi, with his remaining men.

Maury wanted to join the remains of the Army of Tennessee in North Carolina. However, hearing of Johnston's surrender to Sherman on April 26 he soon ran out of options. Ultimately Maury surrendered Mobile's about four thousand men to the Union army on May 5 at Citronelle, Alabama.[30]

Andrew Johnson's May 9 Declaration (May 9, 1865)

Despite the fact that there were still small pockets of resistance in the South, the president declared that the armed resistance was "virtually" ended and that nations or ships still harboring fugitives would be denied entry into U.S. ports. Persons found aboard such vessels would no longer be given immunity from prosecution of their crimes.[31]

Capture of Jefferson Davis (May 10, 1865)

On May 10, Union cavalrymen, under Major General James H. Wilson, captured Confederate President Jefferson Davis after he fled Richmond, Virginia, following its evacuation in the early part of April 1865. On May 5, 1865, in Washington, Georgia, Davis had held the last meeting of his Cabinet. At that time, the Confederate government was declared dissolved.[4]

The sequence of events that led to Davis' capture began early in May 1865, when the 4th Michigan Cavalry was set up in an encampment of tents at Macon, Georgia. The military unit of several battalions was commanded by Lieut. Col. Ben Pritchard. On May 7, he was given orders to join many other units searching for the Confederate president. Pritchard's troops scouted through the country along the Ocmulgee River, and by the next day the Michiganders had come to Hawkinsville, Georgia, about fifty miles south of Macon, from where they continued along the river to Abbeville, Georgia. There, Pritchard learned from Lieutenant Colonel Henry Harnden that his First Wisconsin Cavalry was hot on Davis's trail. After a meeting between the two colonels, Harnden and his men headed off towards Irwinville, some twenty miles south of their position.[32]

Pritchard received word from local residents that on the night before a party, probably including the Confederate President, had crossed the Ocmulgee River just north of Abbeville. Since there were two roads to Irwindale, one of which had been taken by Harnden and his men, Pritchard decided to take the other, to see if he could capture Davis. He took with him about a hundred and forty men and their horses, while the balance of the Michiganders stayed on the Ocmulgee River near Abbeville. Some seven hours later, at 1 A.M. on May 10, Pritchard arrived at Irwindale. There was no evidence of Harnden's men being there yet.[32]

Pritchard learned from local residents that about a mile and a half to the north there was a military camp. Not knowing whether this was Davis and his group or the 1st Wisconsin Cavalry, he approached cautiously. He soon identified the camp as Davis's. At first dawn, Pritchard charged the camp, which was so surprised and overwhelmed that it offered no resistance and yielded immediately.[32]

About ten minutes after the surrender, Pritchard heard rapid gunfire to the north. He left Davis and the captured men in the hands of his 21-year-old adjutant. Once he had approached the gunfire, he realized it was the 4th Michigan and the 1st Wisconsin shooting at each other with Spencer repeating carbines, neither realizing who they were shooting at. Pritchard immediately ordered his men to stop and shouted to the 1st Wisconsin to identify the parties. In the five-minute skirmish, the 1st Wisconsin Cavalry had suffered eight men wounded, while the 4th Michigan Cavalry had lost two men killed and one wounded.[32]

Back at camp, Pritchard's adjutant was almost fooled into letting Davis escape by a ruse. Davis's wife had persuaded the adjutant to let her "old mother" go to fetch some water. The adjutant allowed this, and walked away from their tent. Mrs. Davis and a person dressed as an old woman then left the tent to go for the water. One of the other ranking officers noticed the "old woman" was wearing men's riding boots with spurs. Immediately, they were stopped and the woman's overcoat and black head shawl were removed, to reveal Davis himself.[33] The plan of escape thus failed.[34] The Confederate president was subsequently held prisoner for two years in Fort Monroe, Virginia.[35]

Department of Florida and South Georgia (May 10, 1865)

In 1864, Major General Samuel Jones commanded the Departments of Florida, South Carolina, and South Georgia, with his headquarters in Pensacola, Florida. His primary orders were to guard the coastal areas of these states and to destroy Union gunboats. He also destroyed all the machinery and sawmills that would be beneficial to the Union armies.[36]

In the early part of 1865, Jones was transferred to Tallahassee, soon after Savannah had fallen to Sherman and the Union forces in December 1864. There, Jones headquartered the District of Florida. On May 10, at Tallahassee, he surrendered about eight thousand troops to Brigadier General Edward M. McCook. In military action east of the Mississippi River, the city of Tallahassee was the only Confederate state capital not captured during the Civil War.[36]

Northern Sub-District of Arkansas (May 11, 1865)

Wittsburg, Arkansas (the county seat of Cross County from 1868 through 1886), would witness one of the final acts in the American Civil War. This happened after the collapse of Confederate forces east of the Mississippi. Major General Grenville M. Dodge sent Lieutenant Colonel Charles W. Davis of the 51st Illinois Infantry on April 30, 1865, to Arkansas to seek the surrender of Confederate Brigadier General "Jeff" Meriwether Thompson, commander of Confederate troops in the northeast portion of Arkansas. Davis, arriving at Chalk Bluff (now non-extant) in Clay County, Arkansas, on the St. Francis River, sent communications to Thompson asking that they have a conference. These two officers met on May 9 to negotiate a surrender.[37]

Thompson requested from Davis two days to work out the details of the surrender with his officers. The Confederates under the command of Thompson agreed to surrender all the troops in the area on May 11, 1865.[lower-alpha 1] They picked Wittsburg and Jacksonport, Arkansas, as the sites where Thompson's five thousand military troops would gather to receive their paroles. Ultimately Thompson surrendered about seventy-five hundred men all total that were under his command consisting of 1,964 enlisted men with 193 officers paroled at Wittsburg in May 1865 and 4,854 enlisted men with 443 officers paroled at Jacksonport on June 6, 1865.[6][38]

North Georgia (May 12, 1865)

The surrender of between 3000 and 4000 soldiers under Brigadier General William T. Wofford's command took place at Kingston, Georgia, and was received by Brig. Gen. Henry M. Judah on May 12, 1865. There were several letters between the various generals involved in the negotiation of this surrender, including Wofford, Judah, William D. Whipple and Robert S. Granger.[39]

Colonel Louis Merrill kept the Headquarters Department of the Cumberland in Nashville, Tennessee informed and according to a letter he wrote on May 4, 1865, there were about 10,000 soldiers under Wofford's command, "on paper." These consisted of all the Confederate troops in northwestern Georgia, however only about a third could actually be collected as the rest were deserters. From this group there were a number of soldiers that resisted General Wofford's efforts to make them follow his commands.[6]

There is a Georgia historical marker in Kingston, Georgia, in Bartow County at the intersection of West Main Street and Church Street to denote where this surrender took place. It further explains that the Confederate soldiers were given rations after their release.

Palmito Ranch (May 13, 1865)

The last land battle of the Civil War took place near Brownsville, Texas, and it was won by the Confederates. The Confederates held the city of Brownsville in the early part of 1865. In January or February Major General Lew Wallace was sent by the Union government to Texas. On March 11 Wallace had a meeting with the two major Confederate commanders of the region, Brigadier General James Slaughter and Colonel John "Rip" Ford, under the premise that the official purpose was the "rendition of criminals." The real reason was to agree that any fighting in the region would be pointless and negotiate an unofficial indefinite cease fire. Slaughter and Ford, at this point in time, occupied Fort Brown near Brownsville.[40]

In May Colonel Theodore H. Barrett was in temporary command of Union troops at Brazos Santiago Island. He had little military field experience and desired, it is surmised, "to establish for himself some notoriety before the war closed." Barrett knew that an attack on Fort Brown was in violation of orders from headquarters, since the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia already surrendered by Lee at Appomattox on April 9 and many other Confederate forces had surrendered or disbanded by then. In spite of these known facts Barrett decided anyway to go ahead with his plans.[41]

On May 12, Barrett instructed Colonel David Branson of the 34th Indiana Veteran Volunteer Infantry to attack the Confederate encampment at Brazos Santiago Depot near Fort Brown. Barrett commanded the 62nd United States Colored Infantry and the 2nd Texas Cavalry, and advanced towards Fort Brown with the intention of reoccupying Brownsville with Union forces thinking they would not encounter any problems, assuming all the Confederates surely had heard of Lee's surrender by this time. To their surprise they encountered Confederates that did not know of Lee's surrender.[41]

A ferocious battle erupted at Palmito Ranch, about 12 miles outside Brownsville. The battle was lost by Barrett's Union regiments mainly because they were outmaneuvered and overrun. Of the original 300 Union troops that fought at Palmito Ranch, they lost over one third, mostly to capture with a few killed or seriously injured.

Trans-Mississippi Department (May 26, 1865)

Confederate leaders asked General Kirby Smith to send reinforcements from his Army of the Trans-Mississippi east of the Mississippi River, in the spring of 1864 following the Battle of Mansfield and the Battle of Pleasant Hill. This was not practicable due to the Union naval control of the Mississippi River and the unwillingness of western troops to be transferred east of the river. Smith instead dispatched Major General Sterling Price and his cavalry on an invasion of Missouri that was ultimately not successful. Thereafter the war west of the Mississippi River was principally one of small raids.

By May 26 1865, a representative of Smith's negotiated and signed surrender documents with a representative of Major General Edward Canby in Shreveport, Louisiana, then took custody of Smith's force of 43,000 soldiers when they surrendered, by then the only significant Confederate forces left west of the Mississippi River. With this ended all organized Southern military resistance to the Union forces. Smith signed the surrender papers on June 2 on board the U.S.S. Fort Jackson just outside Galveston Harbor.[42]

Camp Napoleon Council (May 26, 1865)

The Native American tribes of the Indian Territory realized that the Confederacy could no longer fulfill its commitments to them. Therefore, the Camp Napoleon Council was called to draft an agreement to present a united front as they negotiated a return of their loyalty to the United States. Native American tribes further west, many of them also at war with the United States troops, were also invited to take part, and several of them did.[43]

At the end of the meeting, on May 26, 1865, the council appointed commissioners (no more than five for each tribe) to attend a conference with the U.S. government at Washington D.C., at which the results of the Camp Napoleon Council would be presented and discussed. However, the U.S. government refused to treat with such a large group representing so many tribes. Furthermore the government regarded the Camp Napoleon meeting as unofficial and unauthorized. President Johnson later called for a meeting at Fort Smith (called the Fort Smith Council), which was held in September, 1865.[44]

Surrender of Cherokee chief Stand Watie (June 23, 1865)

Cherokee Brigadier General Stand Watie commanded the Confederate Indians when he surrendered on June 23.[45] This was the last significant Confederate active force.[46] Watie formed the Cherokee Mounted Rifles. He was a guerrilla fighter commanding Cherokee, Seminole, Creek, and Osage Indian soldiers.[47] They earned a notorious reputation for their bold and brave fighting. Yearly, Federal troops all over the western United States hunted for Watie, but they never captured him. He surrendered on June 23 at Fort Towson, in the Choctaw Nations area at the village of Doaksville (now a ghost town) of the Indian Territory, being the last Confederate general to surrender in the American Civil War.[48]

CSS Shenandoah (November 6, 1865)

The CSS Shenandoah was commissioned as a commerce raider by the Confederacy to interfere with Union shipping and hinder their efforts in the American Civil War. A Scottish-built merchant ship originally called the Sea King, it was secretly purchased by Confederate agents in September 1864. Captain James Waddell renamed the ship Shenandoah after she was converted to a warship off the coast of Spain on October 19, shortly after leaving England. William Conway Whittle, Waddell's right-hand man, was the ship's executive officer.[49]

The Shenandoah, sailing south then east across the Indian Ocean and into the South Pacific, was in Micronesia at the Island of Ponape (called Ascension Island by Whittle) at the time of the surrender of Lee's Army of Northern Virginia to the Union forces on April 9, 1865.[50] Waddell had already captured and disposed of thirteen Union merchantmen.

The Shenandoah destroyed one more prize in the Sea of Okhotsk, north of Japan, then continued to the Aleutians and into the Bering Sea and Arctic Ocean, crossing the Arctic Circle on June 19.[51] Continuing then south along the coast of Alaska the Shenandoah came upon a fleet of Union ships whaling on June 22.[51] She opened continuous fire, destroying a major portion of the Union whaling fleet.[51] Capt. Waddell took aim at a fleeing whaler, Sophia Thornton, and at his signal, the gunner jerked a wrist strap and fired the last two shots of the American Civil War.[52] Shenandoah had so far captured and burned eleven ships of the American whaling fleet while in Arctic waters.[51]

Waddell finally learned of Lee's surrender on June 27 when the captain of the prize Susan & Abigail produced a newspaper from San Francisco. The same paper contained Confederate President Jefferson Davis's proclamation that the "war would be carried on with re-newed vigor".[53] Shenandoah proceeded to capture a further ten whalers in the following seven hours. Waddell then steered Shenandoah south, intending to raid the port of San Francisco which he believed to be poorly defended. En route they encountered an English barque, Barracouta, on August 2 from which Waddell learned of the final collapse of the Confederacy including the surrenders of Johnston's, Kirby Smith's, and Magruder's armies and the capture of President Davis. The long log entry of the Shenandoah for August 2, 1865, begins "The darkest day of my life." Captain Waddell realized then in his grief that they had taken innocent unarmed Union whaling ships as prizes when the rest of the country had ended hostilities.[54]

Following the orders of the captain of the Barracouta, Waddell immediately converted the warship back to a merchant ship, storing her cannon below, discharging all arms, and repainting the hull.[54][55] At this point, Waddell decided to sail back to England and surrender the Shenandoah in Liverpool. Surrendering in an American port carried the certainty of facing a court with a Union point of view and the very real risk of a trial for piracy, for which he and the crew could be hanged. Sailing south around Cape Horn and staying well off shore to avoid shipping that might report Shenandoah's position, they saw no land for another 9,000 miles until they arrived back in England, having logged a total of over 58,000 miles around the world in a year's travel—the only Confederate ship to circumnavigate the globe.[56]

Thus the final Confederate surrender of the war did not occur until November 6, 1865, when Waddell's ship reached Liverpool and was surrendered to Capt. R. N. Paynter, commander of HMS Donegal of the British Royal Navy.[54][57][58] The Shenandoah was officially surrendered by letter to the British Prime Minister, the Earl Russell.[59][60][61][62] Ultimately, after an investigation by the British Admiralty court, Waddell and his crew were exonerated of doing anything that violated the laws of war and were unconditionally released. Shenandoah herself was sold to Sultan Majid bin Said of Zanzibar in 1866 and renamed El Majidi.[63] Several of the crew moved to Argentina to become farmers and eventually returned to the United States.

Presidential proclamation ending the war (August 20, 1866)

On August 20, 1866, United States President Andrew Johnson signed a Proclamation—Declaring that Peace, Order, Tranquillity, and Civil Authority Now Exists in and Throughout the Whole of the United States of America.[64] It cited the end of the insurrection in Texas, and declared

... that the insurrection which heretofore existed in the State of Texas is at an end and is to be henceforth so regarded in that State as in the other States before named in which the said insurrection was proclaimed to be at an end by the aforesaid proclamation of the 2nd day of April, 1866. And I do further proclaim that the said insurrection is at an end and that peace, order, tranquillity, and civil authority now exist in and throughout the whole of the United States of America.

See also

Notes

- On this date, Missouri Brig. Gen. M. Jeff Thompson surrendered the State Guard’s forces in Arkansas to Lieut. Col. Charles W. Davis, assistant provost marshal general for Maj. Gen. Grenville M. Dodge.

Sources

References

- Heidler, pp. 703–06.

- Harrell, pp. 384–90.

- Davis, To Appomattox: Nine April Days, 1865, pp. 307, 309, 312, 318, 322–8, 341–403.

- Korn, pp. 160, 162.

- Wagner, Margaret E.; Gallagher, Gary W.; McPherson, James M. (2009). The Library of Congress Civil War Desk Reference. New York City: Simon and Schuster. p. 159. ISBN 978-1-4391-4884-6.

- United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: a compilation of the official records of the Union and Confederate armies, pp. 735–7.

- Schooler, The Last Shot, Introduction

- "Union / Victory! / Peace! / Surrender of General Lee and His Whole Army". The New York Times. April 10, 1865. p. 1.

- "Most Glorious News of the War / Lee Has Surrendered to Grant ! / All Lee's Officers and Men Are Paroled". Savannah Daily Herald. Savannah, Georgia, U.S. April 16, 1865. pp. 1, 4.

- Sutherland, p. 188

- Sutherland, p. 189.

- "The Last Battle of the Civil War". Archived from the original on August 2, 2017. Retrieved February 28, 2010.

- Columbus, Georgia 1865: The Last True Battle of the Civil War

- "Last Land Battle of the Civil War". Archived from the original on June 24, 2013. Retrieved February 28, 2010.

- Wert, pp. 32–45, 275–89.

- Wert, p. 288

- Wert, p. 289

- Ramage 1999, pp. 266-269.

- Katcher, p. 184.

- Bradley, p. 270.

- Catton, A Stillness at Appomattox, pp. 294–95, 339, 365–66.

- Snow, p. 301.

- Eicher, Longest Night, pp. 834–35.

- Eicher, Civil War High Commands, p. 323.

- Snow, p. 302.

- Wead, p. 173

- Heidler, pp. 584–86.

- Beringer, p. 198

- Peters, Gerhard; Woolley, John T. "Andrew Johnson: "Proclamation 131—Rewards for the Arrest of Jefferson Davis and Others," May 2, 1865". The American Presidency Project. University of California – Santa Barbara. Archived from the original on August 27, 2017. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- Johnson, p. 411.

- https://www.nytimes.com/1865/05/10/news/important-proclamations-belligerent-rights-rebels-end-all-nations-warned-against.html

- Ballard, pp. 97–116.

- Johnson, Pursuit, pp. 197–98.

- Cutting, p. 302.

- Van Doren, p. 912.

- Heidler, p. 1093.

- Filbert, pp. 26–49.

- Jerry and Victor Ponder's "Confederate Surrender and Parole: Jacksonport and Wittsburg, Arkansas, May and June 1865" [Ponder Books, 1995]

- Gelbert, p. 37.

- Hunt, pp. 25–37.

- Hunt, pp. 1–12.

- Cotham, pp. 181–83.

- Alan C. Downs. ""Camp Napoleon Council," Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Accessed August 23, 2015.

- Perry, Dan W. "A Foreordained Commonwealth" Archived February 14, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Chronicles of Oklahoma 14:1 (March 1936) 22-48 (retrieved February 5, 2017)

- Hoxie, p. 679.

- Markowitz, p. 846.

- Brigadier General Stand Waite

- Morris, pp. 68–69

- Baldwin, pp. 1–11.

- Baldwin, pp. 198–205.

- Baldwin, pp. 238–54.

- Baldwin, p. 255.

- LAST CONFEDERATE CRUISER by CORNELIUS E. HUNT one of her officers. 267

- McKenna, p. 340.

- Baldwin, p. 279.

- Baldwin, pp. 275–307.

- Sheehan-Dean, p. 130

- Davis, The Civil War: Strange & Fascinating Facts, p. 213.

- Baldwin, p. 319.

- Thomsen, p. 279.

- Whittle, p. 212.

- Waddell, p. 36.

- http://americancivilwar.com/tcwn/civil_war/Navy_Ships/CSS_Shenandoah.html

- Text of Johnson's proclamation

Bibliography

- Baldwin, John, Last Flag Down: The Epic Journey of the Last Confederate Warship, Crown Publishers, 2007, ISBN 5-557-76085-7, Random House, Incorporated, 2007, ISBN 0-7393-2718-6

- Ballard, Michael B., A Long Shadow: Jefferson Davis and the Final Days of the Confederacy, University of Georgia Press, 1997, ISBN 0-8203-1941-4

- Beringer, Richard E. Why the South Lost the Civil War, University of Georgia Press, 1991, ISBN 0-8203-1396-3

- Bradley, Mark L., This Astounding Close: The Road to Bennett Place, UNC Press, 2000, ISBN 0-8078-2565-4

- Catton, Bruce (1953). A Stillness at Appomattox. Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-04451-8. LCCN 53-9982.

- Comtois, Pierre. "War's Last Battle." America's Civil War, July 1992 (Vol. 5, No. 2)

- Cotham, Edward Terrel, Battle on the Bay: The Civil War Struggle for Galveston, University of Texas Press, 1998, ISBN 0-292-71205-7

- Cutting, Elisabeth, Jefferson Davis – Political Soldier, Read Books, 2007, ISBN 1-4067-2337-1

- Davis, Burke, The Civil War: Strange & Fascinating Facts, Wings Books, 1960 & 1982, ISBN 0-517-37151-0

- Davis, Burke, To Appomattox – Nine April Days, 1865, Eastern Acorn Press, 1992, ISBN 0-915992-17-5

- Eicher, David J., The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War, Simon & Schuster, 2001, ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Eicher, John H., and Eicher, David J., Civil War High Commands, Stanford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8047-3641-3.

- Faust, Drew Gilpin, The Dread Void of Uncertainty": Naming the Dead in the American Civil War, Southern Cultures (magazine) – Volume 11, Number 2, University of North Carolina Press, Summer 2005

- Filbert, Preston, The Half Not Told: The Civil War in a Frontier Town, Stackpole Books, 2001, ISBN 0-8117-1536-1

- Gelbert, Doug, Civil War Sites, Memorials, Museums, and Library Collections: A State-by-state Guidebook to Places Open to the Public, McFarland & Co., 1997, ISBN 0-7864-0319-5

- Harrell, Roger Herman' The 2nd North Carolina Cavalry: Spruill's Regiment in the Civil War, McFarland, 2004, ISBN 0-7864-1777-3

- Heidler, David Stephen et al., Encyclopedia Of The American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History, W. W. Norton & Company, 2002, ISBN 0-393-04758-X

- Hoxie, Frederick E., Encyclopedia of North American Indians: Native American History, Culture, and Life from Paleo-Indians to the Present, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1996, ISBN 0-395-66921-9

- Hunt, Jeffrey William, The Last Battle of the Civil War: Palmetto Ranch, University of Texas Press, 2002, ISBN 0-292-73461-1,back cover

- Johnson, Clint, Pursuit: The Chase, Capture, Persecution, and Surprising Release of Confederate President Jefferson Davis, Kensington Publishing Corp., 2008, ISBN 0-8065-2890-7

- Johnson, Robert Underwood, Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Yoseloff, 1888

- Katcher, Philip, The Civil War Day by Day: Day by Day, MBI Publishing Company, 2007, ISBN 0-7603-2865-X

- Kennedy, Frances H., The Civil War Battlefield Guide, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1990, ISBN 0-395-52282-X

- Korn, Jerry, Pursuit to Appomattox: The Last Battles, Time-Life Books, 1987, ISBN 0-8094-4788-6

- Markowitz, Harvey, American Indians: Ready Reference, vol III, Salem Press, 1995, ISBN 0-89356-760-4

- Marvel, William. "Last Hurrah at Palmetto Ranch." Civil War Times, January 2006 (Vol. XLIV, No. 6)

- McKenna, Robert, The Dictionary of Nautical Literacy, McGraw-Hill Professional, 2003, ISBN 0-07-141950-0

- Morris, John Wesley, Ghost towns of Oklahoma, University of Oklahoma Press, 1977, ISBN 0-8061-1420-7

- Ramage, James A. (1999). Gray Ghost: The Life of Col. John Singleton Mosby. The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-2135-3.

- Schooler, Lynn, The Last Shot, HarperCollins, 2006, ISBN 0-06-052334-4

- Sheehan-Dean, Aaron, Struggle for a Vast Future: The American Civil War, Osprey Publishing, 2007, ISBN 1-84603-213-X

- Silkenat, David. Raising the White Flag: How Surrender Defined the American Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019. ISBN 978-1-4696-4972-6.

- Snow, William P., Lee and His Generals, Gramercy Books, 1867, ISBN 0-517-38109-5.

- Sutherland, Jonathan, African Americans at War: An Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, 2004, ISBN 1-57607-746-2

- Thomsen, Brian, Blue & Gray at Sea: Naval Memoirs of the Civil War, Macmillan, 2004, ISBN 0-7653-0896-7

- Tidwell, William A., April '65: Confederate Covert Action in the American Civil War, Kent State University Press, 1995, ISBN 0-87338-515-2

- United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: a compilation of the official records of the Union and Confederate armies, Government Printing Office, 1902

- Van Doren, Charles Lincoln et al., Webster's Guide to American History: A Chronological, Geographical, and Biographical Survey and Compendium, Merriam-Webster, 1971, ISBN 0-87779-081-7

- Waddell, James Iredell et al., C. S. S. Shenandoah: The Memoirs of Lieutenant Commanding James I. Waddell, Crown Publishers, 1960, Original from the University of Michigan – digitized Dec 5, 2006

- Wead, Doug, All the Presidents' Children: Triumph and Tragedy in the Lives of America's First Families, Simon and Schuster, 2004, ISBN 0-7434-4633-X

- Weigley, Russel F., A Great Civil War: A Military and Political History, 1861–1865, Indiana University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-253-33738-0

- Wert, Jeffry D., Mosby's Rangers, Simon and Schuster, 1991, ISBN 0-671-74745-2

- Whittle, William Conway et al., The Voyage of the CSS Shenandoah: A Memorable Cruise, University of Alabama Press, 2005, ISBN 0-8173-1451-2

- Wright, Mike, What They Didn't Teach You about the Civil War, Presido, 1996, ISBN 0-89141-596-3

Further reading

- Andrews, J. Cutler, The North Reports the Civil War, University of Pittsburgh Press, 1955

- Badeau, Adam, Grant in Peace: From Appomattox to Mount McGregor; a Personal Memoir, S.S. Scranton & Company, 1887

- Beatie, Russel H., The Army of the Potomac, Basic Books, 2002, ISBN 0-306-81141-3

- Boykin, Edward M., The Falling Flag: Evacuation of Richmond, Retreat and Surrender at Appomattox, E.T. Hale, 1874

- Bradford, Ned, Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Gramercy Books, 1988, ISBN 0-517-29820-1

- Chaffin, Tom, Sea of Gray: The Around-the-World Odyssey of the Confederate Raider Shenandoah, Hill and Wang/Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007, ISBN 0-8090-8504-6

- Crotty, Daniel G., Four Years Campaigning in the Army of the Potomac, Dygert Brothers and Company, 1874

- Catton, Bruce (1953). This Hallowed Ground: The Story of the Union Side of the Civil War. Doubleday. ISBN 1-85326-696-5. LCCN 56-5960.

- Coombe, Jack D., Gunfire Around the Gulf: The Last Major Naval Campaigns of the Civil War, Bantam Books, 1999, ISBN 0-553-10731-3

- Craven, Avery, The Coming of the Civil War, University of Chicago Press, 1957, ISBN 0-226-11894-0

- Cunningham, S.A., Confederate Veteran, Confederated Southern Memorial Association et al., 1920

- Davis, Jefferson, The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government, D. Appleton and Company, 1881

- Dunlop, W. S., Lee's Sharpshooters, Tunnah & Pittard, 1899, ISBN 1-58218-613-8

- Gills, Mary Louise, It Happened at Appomattox: The Story of an Historic Virginia Village, Dietz Press, 1948, ISBN 0-87517-038-2

- Kean, Robert Garlick Hill et al., Inside the Confederate Government: The Diary of Robert Garlick Hill Kean, Head of the Bureau of War, Oxford University Press, 1957

- Konstam, Angus et al., Confederate Raider 1861–65, Osprey Publishing, 2003, ISBN 1-84176-496-5

- Konstam, Angus et al., Confederate Blockade Runner 1861–65, Osprey Publishing, 2004, ISBN 1-84176-636-4

- Long, Armistead Lindsay, Memoirs of Robert E. Lee: His Military and Personal History, Embracing a Large Amount of Information Hitherto Unpublished, J. M. Stoddart & Company, 1886

- Longstreet, James, From Manassas to Appomattox: Memoirs of the Civil War in America, J.B. Lippincott, 1908

- Marvel, William, A Place Called Appomattox, UNC Press, 2000, ISBN 0-8078-2568-9

- McPherson, James M., Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War era, Oxford University Press, 1988

- Morgan, Murray, Confederate Raider in the North Pacific: The Saga of the C. S. S. Shenandoah, 1864–65, Washington State University Press, 1995, ISBN 0-585-20703-8

- Schooler, Lynn, The Last Shot: The Incredible Story of the C.S.S. Shenandoah and the True Conclusion of the American Civil War, Thorndike Press, 2005, ISBN 0-7862-8079-4

- Wise, Jennings Cropper, The Long Arm of Lee: The History of the Artillery of the Army of Northern Virginia; with a Brief Account of the Confederate Bureau of Ordnance, J. P. Bell Company, 1915, volume 2

.jpg.webp)