Whip antenna

A whip antenna is an antenna consisting of a straight flexible wire or rod. The bottom end of the whip is connected to the radio receiver or transmitter. The antenna is designed to be flexible so that it does not break easily, and the name is derived from the whip-like motion that it exhibits when disturbed. Whip antennas for portable radios are often made of a series of interlocking telescoping metal tubes, so they can be retracted when not in use. Longer ones, made for mounting on vehicles and structures, are made of a flexible fiberglass rod around a wire core and can be up to 35 ft (10 m) long. The length of the whip antenna is determined by the wavelength of the radio waves it is used with. The most common type is the quarter-wave whip, which is approximately one-quarter of a wavelength long. Whips are the most common type of monopole antenna, and are used in the higher frequency HF, VHF and UHF radio bands. They are widely used as the antennas for hand-held radios, cordless phones, walkie-talkies, FM radios, boom boxes, and Wi-Fi enabled devices, and are attached to vehicles as the antennas for car radios and two-way radios for wheeled vehicles and for aircraft. Larger versions mounted on roofs, balconies and radio masts are used as base station antennas for amateur radio and police, fire, ambulance, taxi, and other vehicle dispatchers.

Radiation pattern

The whip antenna is a monopole antenna, and like a vertical dipole has an omnidirectional radiation pattern, radiating equal radio power in all azimuthal directions (perpendicular to the antenna's axis), with the radiated power falling off with elevation angle to zero on the antenna's axis. Whip antennas less than one-half wavelength long, including the common quarter wave whip, have a single main lobe, and with a perfectly conducting ground plane under it maximum field strength is in horizontal directions, falling monotonically to zero on the axis. With a small or imperfectly conducting ground plane or no ground plane under it, the general result is to tilt the main lobe up so maximum power is no longer radiated horizontally but at an angle into the sky.

Antennas longer than a half-wavelength have patterns consisting of several conical "lobes"; with radiation maxima at several elevation angles; the longer the electrical length of the antenna, the more lobes the pattern has.

Vertical whip antennas are widely used for nondirectional radio communication on the surface of the Earth, where the direction to the transmitter (or the receiver) is unknown or constantly changing, for example in portable FM radio receivers, walkie-talkies, and two-way radios in vehicles. This is because they transmit (or receive) equally well in all horizontal directions, while radiating little radio energy up into the sky where it is wasted.

Length

Whip antennas are normally designed as resonant antennas; the rod acts as a resonator for radio waves, with standing waves of voltage and current reflected back and forth from its ends. Therefore, the length of the antenna rod is determined by the wavelength of the radio waves used. The most common length is approximately one-quarter of the wavelength, called a "quarter-wave whip" (although often shortened by the use of a loading coil; see Electrically short whips below). For example, the common quarter-wave whip antennas used on FM radios in the USA are approximately 75 cm long, which is roughly one-quarter the length of radio waves in the FM radio band, which are 2.78 to 3.41 meters long. Half-wave antennas are also common.

Gain and radiation resistance

A quarter wave vertical antenna working against a perfect infinite ground will have a gain of 5.19 dBi and a radiation resistance of about 36.8 ohms. Whips mounted on vehicles use the metal skin of the vehicle as a ground plane. In hand-held devices usually no explicit ground plane is provided, and the ground side of the antenna's feed line is just connected to the ground on the device's circuit board.[1] Therefore, the radio itself, and possibly the user's hand, serves as a rudimentary ground plane. Since these are no larger than the size of the antenna itself, the combination of whip and radio often functions more as an asymmetrical dipole antenna than as a monopole antenna. The gain will suffer somewhat compared to a half wave metallic dipole or a whip with a well defined ground plane.

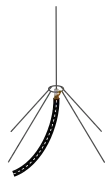

Ground plane antenna

In a whip antenna not mounted on a conductive surface, such as one mounted on a mast, the lack of reflected radio waves from the ground plane causes the lobe of the radiation pattern to be tilted up toward the sky so less power is radiated in horizontal directions, undesireable for terrestrial communication.[2] Also the unbalanced impedance of the monopole element causes RF currents in the supporting mast and on the outside of the ground shield conductor of the coaxial feedline. To prevent this, with stationary whips mounted on structures, an artificial "ground plane" consisting of three or four rods a quarter-wavelength long connected to the opposite side of the feedline, extending horizontally from the base of the whip, is often used.[2] This is called a ground plane antenna.[3] These few short wire elements serve to receive the displacement current from the driven element and return it to the ground conductor of the transmission line, making the antenna behave as if it has a continuous conducting plane under it. Often (see pictures) the ground plane rods are sloped downward, to lower the main lobe of the radiation pattern closer to horizontal and increase the normal 36.8 ohm radiation resistance closer to 50 ohms to provide a better impedance match with standard 50 ohm coaxial cable feedline.

Electrically short whips

To reduce the length of a whip antenna to make it less cumbersome, an inductor (loading coil) is often added in series with it. This allows the antenna to be made much shorter than the normal length of a quarter-wavelength, and still be resonant, by cancelling out the capacitive reactance of the short antenna. The coil is added at the base of the whip (called a base-loaded whip) or occasionally in the middle (center-loaded whip). In the most widely used form, the rubber ducky antenna, the loading coil is integrated with the antenna itself by making the whip out of a narrow helix of springy wire. The helix distributes the inductance along the antenna's length, improving the radiation pattern, and also makes it more flexible. Another alternative occasionally used to shorten the antenna is to add a "capacity hat", a metal screen or radiating wires, at the end. However all these electrically short whips have lower gain than a full length quarter-wave whip.

Multi-band operation is possible with coils at about one-half or one-third and two-thirds that do not affect the aerial much at the lowest band, but it creates the effect of stacked dipoles at a higher band (usually ×2 or ×3 frequency).

At higher frequencies (2.4 GHz, but military whips for 50 MHz to 80 MHz band exist, and are standard issue for the SINCGARS radio in the 30–88 MHz range), the feed coax can go up the centre of a tube. The insulated junction of the tube and whip is fed from the coax and the lower tube end where coax cable enters has an insulated mount. This kind of vertical whip is a full dipole and thus needs no ground plane. It generally works better several wavelengths above ground, hence the limitation normally to microwave bands.

Vehicle antenna damages

Whip antennas on vehicles can be damaged by automatic car wash equipment, especially those that use spinning brushes to abrasively rub dirt off the exterior of the vehicle body.[4] Because the brushes must make contact with the vehicle surface, they can bend or completely break off whip antennas. These antennas are generally recommended to be removed or retracted so that the brushes do not make contact, or the vehicle owner should only use a "touchless" spray jet automatic car wash.

Image gallery

See also

- Tactical Vest Antenna System

- Waves (Juno) (Uses two whip antennas for one of its sensors)

- FIELDS (Uses four whip antennas on the Parker Solar Probe)

References

- Chen, Zhi Ning. Antennas for Portable Devices. Chichester: John Wiley, 2007. Print.

- Kraus, John D. (1988). Antennas, 2nd Ed. Tata McGraw-Hill. pp. 721–724. ISBN 0-07-463219-1.

- Wallace, Richard; Andreasson, Krister (2005). "ground+plane+antenna" Introduction to RF and Microwave Passive Components. Artech House. pp. 85–87. ISBN 9781630810092.

- Auto Laundry News - August 2013, Damage Claims — Documentation and an Established Procedure Are Key, By Allen Spears Accessed Nov 28, 2015 Link