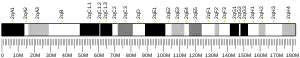

ACTC1

ACTC1 encodes cardiac muscle alpha actin.[5][6] This isoform differs from the alpha actin that is expressed in skeletal muscle, ACTA1. Alpha cardiac actin is the major protein of the thin filament in cardiac sarcomeres, which are responsible for muscle contraction and generation of force to support the pump function of the heart.

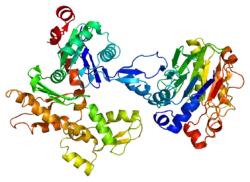

Structure

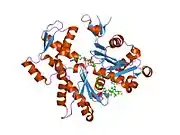

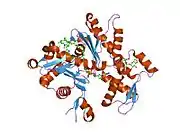

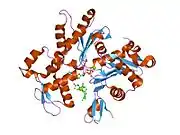

Cardiac alpha actin is a 42.0 kDa protein composed of 377 amino acids.[7][8] Cardiac alpha actin is a filamentous protein extending from a complex mesh with cardiac alpha-actinin (ACTN2) at Z-lines towards the center of the sarcomere. Polymerization of globular actin (G-actin) leads to a structural filament (F-actin) in the form of a two-stranded helix. Each actin can bind to four others. The atomic structure of monomeric actin was solved by Kabsch et al.,[9] and closely thereafter this same group published the structure of the actin filament.[10] Actins are highly conserved proteins; the alpha actins are found in muscle tissues and are a major constituent of the contractile apparatus. Cardiac (ACTC1) and skeletal (ACTA1) alpha actins differ by only four amino acids (Asp4Glu, Glu5Asp, Leu301Met, Ser360Thr; cardiac/skeletal). The actin monomer has two asymmetric domains; the larger inner domain comprised by sub-domains 3 and 4, and the smaller outer domain by sub-domains 1 and 2. Both the amino and carboxy-termini lie in sub-domain 1 of the outer domain.

Function

Actin is a dynamic structure that can adapt two states of flexibility, with the greatest difference between the states occurring as a result of movement within sub-domain 2.[11] Myosin binding increases the flexibility of actin,[12] and cross-linking studies have shown that myosin subfragment-1 binds to actin amino acid residues 48-67 within actin sub-domain 2, which may account for this effect.[13]

It has been suggested that the ACTC1 gene has a role during development. Experiments in chick embryos found an association between ACTC1 knockdown and a reduction in the atrial septa.[14]

Clinical significance

Polymorphisms in ACTC1 have been linked to Dilated Cardiomyopathy in a small number of Japanese patients.[15] Further studies in patients from South Africa found no association.[16] The E101K missense mutation has been associated with Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy[17][18][19][20] and Left Ventricular Noncompaction.[21] Another mutation has in the ACTC1 gene has been associated with atrial septal defects.[14]

References

- GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000159251 - Ensembl, May 2017

- GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000068614 - Ensembl, May 2017

- "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

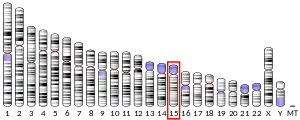

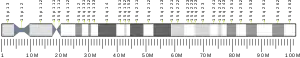

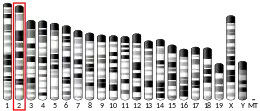

- Kramer PL, Luty JA, Litt M (Jul 1992). "Regional localization of the gene for cardiac muscle actin (ACTC) on chromosome 15q". Genomics. 13 (3): 904–5. doi:10.1016/0888-7543(92)90185-U. PMID 1639426.

- "Entrez Gene: ACTC1 actin, alpha, cardiac muscle 1".

- "Protein Information – Basic Information: Protein COPaKB ID: P68032". Cardiac Organellar Protein Atlas Knowledgebase. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2015-03-15.

- Zong NC, Li H, Li H, Lam MP, Jimenez RC, Kim CS, Deng N, Kim AK, Choi JH, Zelaya I, Liem D, Meyer D, Odeberg J, Fang C, Lu HJ, Xu T, Weiss J, Duan H, Uhlen M, Yates JR, Apweiler R, Ge J, Hermjakob H, Ping P (Oct 2013). "Integration of cardiac proteome biology and medicine by a specialized knowledgebase". Circulation Research. 113 (9): 1043–53. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301151. PMC 4076475. PMID 23965338.

- Kabsch W, Mannherz HG, Suck D, Pai EF, Holmes KC (Sep 1990). "Atomic structure of the actin:DNase I complex". Nature. 347 (6288): 37–44. Bibcode:1990Natur.347...37K. doi:10.1038/347037a0. PMID 2395459.

- Holmes KC, Popp D, Gebhard W, Kabsch W (Sep 1990). "Atomic model of the actin filament". Nature. 347 (6288): 44–9. Bibcode:1990Natur.347...44H. doi:10.1038/347044a0. PMID 2395461.

- Egelman EH, Orlova A (Apr 1995). "New insights into actin filament dynamics". Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 5 (2): 172–80. doi:10.1016/0959-440x(95)80072-7. PMID 7648318.

- Orlova A, Egelman EH (Jul 1993). "A conformational change in the actin subunit can change the flexibility of the actin filament". Journal of Molecular Biology. 232 (2): 334–41. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1993.1393. PMID 8345515.

- Bertrand R, Derancourt J, Kassab R (May 1994). "The covalent maleimidobenzoyl-actin-myosin head complex. Cross-linking of the 50 kDa heavy chain region to actin subdomain-2". FEBS Letters. 345 (2–3): 113–9. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(94)00398-x. PMID 8200441.

- Matsson H, Eason J, Bookwalter CS, Klar J, Gustavsson P, Sunnegårdh J, Enell H, Jonzon A, Vikkula M, Gutierrez I, Granados-Riveron J, Pope M, Bu'Lock F, Cox J, Robinson TE, Song F, Brook DJ, Marston S, Trybus KM, Dahl N (Jan 2008). "Alpha-cardiac actin mutations produce atrial septal defects". Human Molecular Genetics. 17 (2): 256–65. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddm302. PMID 17947298.

- Takai E; et al. (Oct 1999). "Mutational analysis of the cardiac actin gene in familial and sporadic dilated cardiomyopathy". Am J Med Genet. 86 (4): 325–7. doi:10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19991008)86:4<325::aid-ajmg5>3.0.co;2-u. PMID 10494087.

- Mayosi BM; et al. (Oct 1999). "Cardiac and skeletal actin gene mutations are not a common cause of dilated cardiomyopathy". J Med Genet. 36 (10): 796–7. doi:10.1136/jmg.36.10.796. PMC 1734242. PMID 10528865.

- Olson TM, Doan TP, Kishimoto NY, Whitby FG, Ackerman MJ, Fananapazir L (Sep 2000). "Inherited and de novo mutations in the cardiac actin gene cause hypertrophic cardiomyopathy". Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 32 (9): 1687–94. doi:10.1006/jmcc.2000.1204. PMID 10966831.

- Arad M, Penas-Lado M, Monserrat L, Maron BJ, Sherrid M, Ho CY, Barr S, Karim A, Olson TM, Kamisago M, Seidman JG, Seidman CE (Nov 2005). "Gene mutations in apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy". Circulation. 112 (18): 2805–11. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.547448. PMID 16267253.

- Monserrat L, Hermida-Prieto M, Fernandez X, Rodríguez I, Dumont C, Cazón L, Cuesta MG, Gonzalez-Juanatey C, Peteiro J, Alvarez N, Penas-Lado M, Castro-Beiras A (Aug 2007). "Mutation in the alpha-cardiac actin gene associated with apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, left ventricular non-compaction, and septal defects". European Heart Journal. 28 (16): 1953–61. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehm239. PMID 17611253.

- Morita H, Rehm HL, Menesses A, McDonough B, Roberts AE, Kucherlapati R, Towbin JA, Seidman JG, Seidman CE (May 2008). "Shared genetic causes of cardiac hypertrophy in children and adults". The New England Journal of Medicine. 358 (18): 1899–908. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa075463. PMC 2752150. PMID 18403758.

- Klaassen S, Probst S, Oechslin E, Gerull B, Krings G, Schuler P, Greutmann M, Hürlimann D, Yegitbasi M, Pons L, Gramlich M, Drenckhahn JD, Heuser A, Berger F, Jenni R, Thierfelder L (Jun 2008). "Mutations in sarcomere protein genes in left ventricular noncompaction". Circulation. 117 (22): 2893–901. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.746164. PMID 18506004.

Further reading

- Snásel J, Pichová I (1997). "The cleavage of host cell proteins by HIV-1 protease". Folia Biologica. 42 (5): 227–30. doi:10.1007/BF02818986. PMID 8997639.

- Bearer EL, Prakash JM, Li Z (2002). "Actin dynamics in platelets". A Survey of Cell Biology. International Review of Cytology. 217. pp. 137–82. doi:10.1016/S0074-7696(02)17014-8. ISBN 978-0-12-364621-7. PMC 3376087. PMID 12019562.

- Elzinga M, Maron BJ, Adelstein RS (Jan 1976). "Human heart and platelet actins are products of different genes". Science. 191 (4222): 94–5. Bibcode:1976Sci...191...94E. doi:10.1126/science.1246600. PMID 1246600.

- Adams LD, Tomasselli AG, Robbins P, Moss B, Heinrikson RL (Feb 1992). "HIV-1 protease cleaves actin during acute infection of human T-lymphocytes". AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses. 8 (2): 291–5. doi:10.1089/aid.1992.8.291. PMID 1540415.

- Dawson SJ, White LA (May 1992). "Treatment of Haemophilus aphrophilus endocarditis with ciprofloxacin". The Journal of Infection. 24 (3): 317–20. doi:10.1016/S0163-4453(05)80037-4. PMID 1602151.

- Watkins C, Bodfish P, Warne D, Nyberg K, Spurr NK (Dec 1991). "Dinucleotide repeat polymorphism in the human alpha-cardiac actin gene, intron IV (ACTC), detected using the polymerase chain reaction". Nucleic Acids Research. 19 (24): 6980. doi:10.1093/nar/19.24.6980-a. PMC 329379. PMID 1762945.

- Tomasselli AG, Hui JO, Adams L, Chosay J, Lowery D, Greenberg B, Yem A, Deibel MR, Zürcher-Neely H, Heinrikson RL (Aug 1991). "Actin, troponin C, Alzheimer amyloid precursor protein and pro-interleukin 1 beta as substrates of the protease from human immunodeficiency virus". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 266 (22): 14548–53. PMID 1907279.

- Shoeman RL, Kesselmier C, Mothes E, Höner B, Traub P (Jan 1991). "Non-viral cellular substrates for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease". FEBS Letters. 278 (2): 199–203. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(91)80116-K. PMID 1991513.

- Buckingham M, Alonso S, Barton P, Cohen A, Daubas P, Garner I, Robert B, Weydert A (Dec 1986). "Actin and myosin multigene families: their expression during the formation and maturation of striated muscle". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 25 (4): 623–34. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320250405. PMID 3789022.

- Engel JN, Gunning PW, Kedes L (Aug 1981). "Isolation and characterization of human actin genes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 78 (8): 4674–8. Bibcode:1981PNAS...78.4674E. doi:10.1073/pnas.78.8.4674. PMC 320222. PMID 6272269.

- Humphries SE, Whittall R, Minty A, Buckingham M, Williamson R (Oct 1981). "There are approximately 20 actin gene in the human genome". Nucleic Acids Research. 9 (19): 4895–908. doi:10.1093/nar/9.19.4895. PMC 327487. PMID 6273789.

- Hamada H, Petrino MG, Kakunaga T (Oct 1982). "Molecular structure and evolutionary origin of human cardiac muscle actin gene". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 79 (19): 5901–5. Bibcode:1982PNAS...79.5901H. doi:10.1073/pnas.79.19.5901. PMC 347018. PMID 6310553.

- Gunning P, Ponte P, Kedes L, Eddy R, Shows T (Mar 1984). "Chromosomal location of the co-expressed human skeletal and cardiac actin genes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 81 (6): 1813–7. Bibcode:1984PNAS...81.1813G. doi:10.1073/pnas.81.6.1813. PMC 345011. PMID 6584914.

- Gunning P, Ponte P, Blau H, Kedes L (Nov 1983). "alpha-skeletal and alpha-cardiac actin genes are coexpressed in adult human skeletal muscle and heart". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 3 (11): 1985–95. doi:10.1128/mcb.3.11.1985. PMC 370066. PMID 6689196.

- Ueyama H, Inazawa J, Ariyama T, Nishino H, Ochiai Y, Ohkubo I, Miwa T (Mar 1995). "Reexamination of chromosomal loci of human muscle actin genes by fluorescence in situ hybridization". The Japanese Journal of Human Genetics. 40 (1): 145–8. doi:10.1007/BF01874078. PMID 7780165.

- Moroianu J, Riordan JF (Mar 1994). "Nuclear translocation of angiogenin in proliferating endothelial cells is essential to its angiogenic activity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 91 (5): 1677–81. Bibcode:1994PNAS...91.1677M. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.5.1677. PMC 43226. PMID 8127865.

- Dunwoodie SL, Joya JE, Arkell RM, Hardeman EC (Apr 1994). "Multiple regions of the human cardiac actin gene are necessary for maturation-based expression in striated muscle". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 269 (16): 12212–9. PMID 8163527.

- Shuster CB, Lin AY, Nayak R, Herman IM (1997). "Beta cap73: a novel beta actin-specific binding protein". Cell Motility and the Cytoskeleton. 35 (3): 175–87. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1996)35:3<175::AID-CM1>3.0.CO;2-8. PMID 8913639.

External links

- Mass spectrometry characterization of human ACTC1 at COPaKB

- GeneReviews/NIH/NCBI/UW entry on Familial Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Overview

- Human ACTC1 genome location and ACTC1 gene details page in the UCSC Genome Browser.