Politics of climate change

The complex politics of global warming results from numerous cofactors arising from the global economy's dependence on carbon dioxide (CO

2) emitting fossil fuels; and because greenhouse gases such as CO

2, methane and N

2O (mostly from agriculture) cause global warming.[1]

- Implications to all aspects of a nation-state's economy: The vast majority of the world economy relies on energy sources or manufacturing techniques that release greenhouse gases at almost every stage of production, transportation, storage, delivery & disposal while a consensus of the world's scientists attribute global warming to the release of CO

2 and other greenhouse gases. This intimate linkage between global warming and economic vitality implicates almost every aspect of a nation-state's economy;[2] - Industrialization of the developing world: As developing nations industrialize their energy needs increase and since conventional energy sources produce CO

2, the CO

2 emissions of developing countries are beginning to rise at a time when the scientific community, global governance institutions and advocacy groups are telling the world that CO

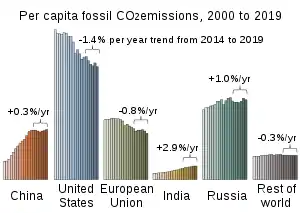

2 emissions should be decreasing. - Metric selection (transparency) and perceived responsibility / ability to respond: Among the countries of the world, disagreements exist over which greenhouse gas emission metrics should be used like total emissions per year, per capita emissions per year, CO2 emissions only, deforestation emissions, livestock emissions or even total historical emissions. Historically, the release of CO

2 has not been even among all nation-states, and nation-states have challenges with determining who should restrict emissions and at what point of their industrial development they should be subject to such commitments; - Vulnerable developing countries and developed country legacy emissions: Some developing nations blame the developed world for having created the global warming crisis because it was the developed countries that emitted most of the CO

2 over the twentieth century and vulnerable countries perceive that it should be the developed countries that should pay to fix the problem; - Consensus-driven global governance models: The global governance institutions that evolved during the 20th century are all consensus driven deliberative forums where agreement is difficult to achieve and even when agreement is achieved it is almost impossible to enforce;

- Well organized and funded special-interest lobbying bodies: Special interest lobbying by well organized groups, such as the fossil fuels lobby, distort and amplify aspects of the challenge.[3][4]

The focus areas for global warming politics are Adaptation, Mitigation, Finance, Technology and Losses which are well quantified and studied but the urgency of the global warming challenge combined with the implication to almost every facet of a nation-state's economic interests places significant burdens on the established largely-voluntary global institutions that have developed over the last century; institutions that have been unable to effectively reshape themselves and move fast enough to deal with this unique challenge. Distrust between developed and developing countries at most international conferences that seek to address the topic add to the challenges.

Most of the policy debate concerning climate change mitigation has been framed by projections for the twenty-first century. The focus on a limited time window, obscures some of the problems associated with climate change. Policy decisions made in the next few decades will have profound impacts on global climate, ecosystems and human societies - not just for this century, but for the next millennia, because near-term climate change policies significantly affect long-term climate change impacts.[5]

Nontraditional environmental challenge

Traditional environmental challenges generally involve behavior by a small group of industries which create products or services for a limited set of consumers in a manner that causes some form of damage to the environment which is clear. As an example, a gold mine might release a dangerous chemical byproduct into a waterway that kills the fish there: a clear environmental damage.[6] By contrast, CO

2 is a naturally occurring colorless odorless trace gas that is essential to the biosphere. Carbon dioxide (CO

2) is produced by all animals and utilized by plants and algae to build their body structures. Plant structures buried for tens of millions of years sequester carbon to form coal, oil and gas which modern industrial societies find essential to economic vitality. Over 80% of world energy consumption is derived from CO

2 emitting fossil fuels.[7] Scientists attribute the increases of CO

2 in the atmosphere to industrial emissions and scientists agree the increase in CO

2 causes global warming. The dependence of many countries on fossil fuels combined with the complexity of the science and the interests of countless interested parties make climate change a non-traditional environmental challenge.

Carbon dioxide and a nation-state's economy

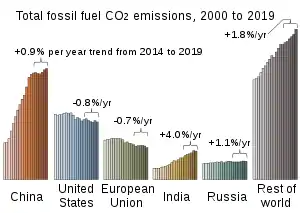

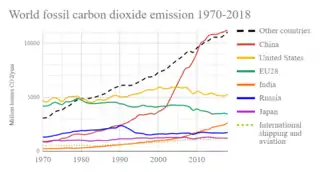

2 emissions in China and the rest of world have surpassed the output of the United States and Europe.[8]

2 at a far faster rate than other primary regions.[8]

The vast majority of developed countries rely on CO

2 emitting energy sources for large components of their economic activity.[9] Fossil fuel energy generally dominates the following areas of an OECD economy:

- agriculture (fertilizers, irrigation, plowing, planting, harvesting, pesticides)

- transportation & distribution (automobiles, shipping, airplanes)

- national defense (armies, tanks, military aircraft, manufacture of munitions)

Perceived lack of adequate advanced low-carbon technologies

As of 2019 fast growing cities in developing countries lack alternatives to traditional high-carbon cement,[11] and the hydrogen economy and carbon capture and storage are not widespread.

Industrialization of the developing world

The developing world sees economic and industrial development as a natural right and the evidence shows that the developing world is industrializing.

Metric selection and perceived responsibility / ability to respond

There are disagreements over which countries should be subject to emissions restrictions.

While the biosphere is indifferent to whether the greenhouse gases are produced by one country or by a multitude, the countries of the world do express an interest in such matters. As such disagreements arise on whether per capita emissions should be used or whether total emissions should be used as a metric for each individual country. Countries also disagree over whether a developing country should share the same commitment as a developed country that has been emitting CO

2 and other greenhouse gases for close to a century.

Some developing countries expressly state that they require assistance if they are to develop, which is seen as a right, in a fashion that does not contribute CO

2 or other greenhouse gases to the atmosphere. Many times, these needs materialize as profound differences in global conferences by countries on the subject and the debates quickly turn to pecuniary matters.

Most developed countries place very modest limits on their willingness to assist developing countries.

Vulnerable developing countries and developed country legacy emissions

Some developing countries fall under the category of vulnerable to climate change. These countries involve small, sometimes isolated, island nations, low lying nations, nations which rely on drinking water from shrinking glaciers etc. These vulnerable countries see themselves as the victims of climate change and some have organized themselves under groups like the Climate Vulnerable Forum. These countries seek climate finance from the developed and the industrializing countries to help them adapt to the impending catastrophes that they see climate change will bring upon them.[12] For these countries climate change is seen as an existential threat and the politics of these countries is to seek reparation and adaptation monies from the developed world and some see it as their right.

Governance

Global warming politics focus areas

Government policies regarding climate change and many official reports on the subject usually revolve around one of the following:

- Adaptation: social and other changes that must be undertaken to successfully adapt to climate change. Adaptation might encompass, but is not limited to, changes in agriculture and urban planning.

- Finance: how countries will finance adaptation to and mitigation of climate change, whether from public or private sources or from wealth/technology transfers from developed countries to developing countries and the management mechanisms for those monies.

- Mitigation: steps and actions that the countries of the world can take to mitigate the effects of climate change.

- Restoration: steps and actions that the countries of the world can take towards climate restoration to reduce the amount of the atmospheric CO2 that causes climate change and aims at reducing global temperatures.

- Technology: the technologies that are needed lower carbon emissions through increasing energy efficiency or replacement or CO

2 emitting technologies and technologies needed to adapt or mitigate climate change. Also encompasses ways that developed countries can support developing countries in adopting new technologies or increasing efficiency. - Loss and damage: first articulated at the 2012 conference and in part based on the agreement that was signed at the 2010 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Cancun. It introduces the principle that countries vulnerable to the effects of climate change may be financially compensated in future by countries that fail to curb their carbon emissions.

- Suppression of science: The U.S. government has also responded by silencing climate scientists and muzzling government whistleblowers.[13] Political appointees at a number of federal agencies prevented scientists from reporting their findings, changed data modeling to arrive at conclusions they had set out a prior to prove, and shut out the input of career scientists of the agencies.[14][15][16][17]

- Government Targeting of Climate Activists: Domestic intelligence services of the U.S. have targeted environmental activists and climate change organizations as "domestic terrorists," investigating them, questioning them, and placing them on national "watchlists" that could make it more difficult for them to board airplanes and could instigate local law enforcement monitoring.[18]

- Stonewalling international cooperation: The United States has rejected international treaties, such as the Kyoto Protocol of 2005 to reduce production of greenhouse gasses,[19] and has said that in 2020 it will withdraw from the Paris Agreement, signed by all UN member countries.[20]

Consensus-driven global political institutions

The primary mechanism for the world to tackle global warming is through the Paris Agreement, which replaced the Kyoto Protocol in 2020, both established under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) treaty.

In 2014, the UN with Peru and France created the Global Climate Action portal for writing and checking all the climate commitments[21][22]

National politics

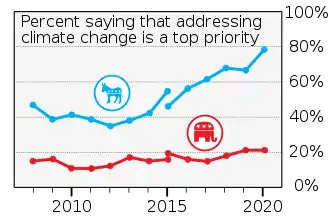

(Discontinuity resulted from survey changing in 2015 from reciting "global warming" to "climate change".)

.jpg.webp)

A 2014 study from the University of Dortmund concluded that countries with center and left-wing governments had higher emission reductions than right-wing governments in OECD countries for the time period 1992–2008.[24] In 2019 climate change became an increasingly important political issue in Germany.[25] In 2019 the highest court in the Netherlands has upheld a landmark ruling that defines protection from the devastation of climate change as a human right and requires the government to be more ambitious in cutting greenhouse gas emissions.[26] The future energy policy of China includes one of the most important climate decisions of the early 2020s: when to stop building coal-fired power stations.[27]

City politics

City politicians advocating measures which have local short-term benefits for their constituents, such as low emission zones which reduce air pollution and so improve health, may also have the co-benefit of reducing greenhouse gas emissions.[28]

Politics of scrapping fossil fuel subsidies

The International Monetary Fund periodically assesses global subsidies for fossil fuels as part of its work on climate, and it found in a working paper published in 2019, that the fossil fuel industry received $5.2 trillion in subsidies in 2017. This amounts to 6.4 percent of the global gross domestic product.[29] In line with these findings, the Central Banks of France and the United Kingdom appealed to stop subsidies to fossil fuels and the European Investment bank has announced it will stop financing fossil fuels projects by the end of 2021.[30]

According to the International Institute for Sustainable Development most attempts to remove fossil fuel subsidies are successful and the keys points are to: consult, compensate poor people affected by the change, and implement step-by-step.[31]

Politics of coal phase out

Sandbag and Europe Beyond Coal have analysed policy in Europe and suggest that coal phase out should be: ambitious, legislated. just. clean, economic, healthy, reliable and smart.[32] Politics may have turned against coal in China in 2020, as China may be trying to show climate leadership after persuasion from the EU.[33] However new coal power plants are still planned to be built.[34]

Politics of trees

As of 2019 the preservation of forests is emerging as a global political issue.[35]

Special interests and lobbying by non-country interested parties

There are numerous special interest groups, organizations, corporations who have public and private positions on the multifaceted topic of global warming. The following is a partial list of the types of special interest parties that have demonstrated an interest in the politics of global warming:

- Fossil fuel companies: Traditional fossil fuel corporations could benefit or lose from stricter global warming regulations. A reduction in the use of fossil fuels could negatively impact fossil fuel corporations.[36][37] However, the fact that fossil fuel companies are a large source of energy, are also the primary source of CO

2, and are engaged in energy trading might mean that their participation in trading schemes and other such mechanisms might give them a unique advantage and makes it unclear whether traditional fossil fuel companies would all and always be against stricter global warming policies.[38] As an example, Enron, a traditional gas pipeline company with a large trading desk heavily lobbied the United States government to regulate CO2: they thought that they would dominate the energy industry if they could be at the center of energy trading.[39] - Farmers and agribusiness are an important lobby but vary in their views on climate change and agriculture[40][41] and, for example, the role of the EU Common Agricultural Policy.[42]

- Financial Institutions: Financial institutions generally support policies against global warming, particularly the implementation of carbon trading schemes and the creation of market mechanisms that associate a price with carbon. These new markets would require trading infrastructures which banking institutions are well positioned to provide. Financial institutions would also be positioned well to invest, trade and develop various financial instruments that they could profit from through speculative positions on carbon prices and the use of brokerage and other financial functions like insurance and derivative instruments.[43]

- Environmental groups: Environmental advocacy groups generally favor strict restrictions on CO

2 emissions. Environmental groups, as activists, engage in raising awareness.[44] - Renewable energy and energy efficiency companies: companies in wind, solar and energy efficiency generally support stricter global warming policies. They would expect their share of the energy market to expand as fossil fuels are made more expensive through trading schemes or taxes.[45]

- Nuclear power companies: support and benefit from carbon pricing.[46]

- Electricity distribution companies: may lose from solar panels but benefit from electric vehicles.[47]

- Traditional retailers and marketers: traditional retailers, marketers, and the general corporations respond by adopting policies that resonate with their customers. If "being green" helps a general corporation, then they could undertake modest programs to please and better align with their customers. However, since the general corporation does not make a profit from their particular position, it is unlikely that they would strongly lobby either for or against a stricter global warming policy position.[48]

- Medics: often say that climate change and air pollution can be tackled together and so save millions of lives.[49]

- Information and communications technology companies: say their products help others combat climate change, tend to benefit from reductions in travel, and many purchase green electricity.[50]

The various interested parties sometimes align with one another to reinforce their message. Sometimes industries will fund specialty nonprofit organizations to raise awareness and lobby on their behest.[51][52] The combinations and tactics that the various interested parties use are nuanced and sometimes unlimited in the variety of their approaches to promote their positions onto the general public.

Interaction of climate science and policy

In the scientific literature, there is an overwhelming consensus that global surface temperatures have increased in recent decades and that the trend is caused primarily by human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases.[53][54][55]

The politicization of science in the sense of a manipulation of science for political gains is a part of the political process. It is part of the controversies about intelligent design[56][57] (compare the Wedge strategy) or Merchants of Doubt, scientists that are under suspicion to willingly obscure findings. e.g. about issues like tobacco smoke, ozone depletion, global warming or acid rain.[58][59] However, e.g. in case of the Ozone depletion, global regulation based on the Montreal Protocol has been successful, in a climate of high uncertainty and against strong resistance[60] while in case of Climate Change, the Kyoto Protocol failed.[61]

While the IPCC process tries to find and orchestrate the findings of global (climate) change research to shape a worldwide consensus on the matter[62] it has been itself been object of a strong politicization.[63] Anthropogenic climate change evolved from a mere science issue to a top global policy topic.[63]

The IPCC process having built a broad science consensus does not hinder governments to follow different, if not opposing goals.[63][64] In case of the ozone depletion challenge, there was global regulation already being installed before a scientific consensus was established.[60]

A linear model of policy-making, based on a more knowledge we have, the better the political response will be does therefore not apply. Knowledge policy,[63] successfully managing knowledge and uncertainties as base of political decision making requires a better understanding of the relation between science, public (lack of) understanding and policy instead.[61][64][65] Michael Oppenheimer confirms limitations of the IPCC consensus approach and asks for concurring, smaller assessments of special problems instead of large scale attempts as in the previous IPCC assessment reports.[66] He claims that governments require a broader exploration of uncertainties in the future.[66]

It has been estimated that only 0.12% of all funding for climate-related research is spent on the social science of climate change mitigation.[67] Vastly more funding is spent on natural science studies of climate change and considerable sums are also spent on studies of impact of and adaptation to climate change.[67] It has been argued that this is a misallocation of resources, as the most urgent puzzle at the current juncture is to work out how to change human behavior to mitigate climate change, whereas the natural science of climate change is already well established and there will be decades and centuries to handle adaptation.[67]

History

Historically, the politics of climate change dates back to several conferences in the late 1960s and the early 1970s under NATO and President Richard Nixon. 1979 saw the first World Climate Conference. 1985 was the year of the Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer and two years later in 1987 saw the signing of the Montreal Protocol under the Vienna convention. This model of using a Framework conference followed by Protocols under the Framework was seen as a promising governing structure that could be used as a path towards a functional governance approach that could be used to tackle broad global multi-nation/state challenges like global warming.

One year later in 1988 the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change was created by the World Meteorological Organization and the United Nations Environment Programme to assess the risk of human-induced climate change. UK Prime Minister at the time Margaret Thatcher strongly supported the IPCC and in 1990 her government founded the Hadley Centre for Climate Prediction and Research.[69][70]

In 1991 the book The First Global Revolution was published by the Club of Rome report which sought to connect environment, water availability, food production, energy production, materials, population growth and other elements into a blueprint for the twenty-first century: political thinking was evolving to look at the world in terms of an integrated global system not just in terms of weather and climate but in terms of energy needs, food, population, etc.

1992 was the year that the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was agreed at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro and the framework entered into force in 1994. The conference established a yearly conference of the parties(COP) to be held to continue work on Protocols which would be enforceable treaties

The phrase "preventing dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system" (also called avoiding dangerous climate change) first appeared in a policy document of a governmental organization, the IPCC's Second Assessment Report: Climate Change 1995,[71] and in 1996 the European Union set a goal of limiting temperature rises to a maximum 2 °C rise in average global temperature.

In 1997 the Kyoto Protocol was created under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in a very similar structure as the Montreal Protocol was under the Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer which would have yearly meetings of the members or CMP meetings. However, in the same year, the US Senate passed the Byrd–Hagel Resolution rejecting Kyoto without more commitments from developing countries.[72]

Since the 1992 UNFCCC treaty, global CO2 emissions have risen significantly and developing countries have grown significantly, with China replacing the United States as the largest emitter of greenhouse gases. To some, the UNFCCC has made significant progress in helping the world become aware of the perils of global warming and has moved the world forward in the addressing of the challenge. To others, the UNFCCC process has been a failure due to its inability to control the rise of greenhouse gas emissions.

The Paris Agreement is a comprehensive new agreement in 2016 that includes both Annex-I and Non-Annex-I parties.

Selective historical timeline of significant climate change political events

- 1969, on Initiative of US President Richard Nixon, NATO tried to establish a third civil column and planned to establish itself as a hub of research and initiatives in the civil region, especially on environmental topics.[73] Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Nixons NATO delegate for the topic[73] named acid rain and the greenhouse effect as suitable international challenges to be dealt by NATO. NATO had suitable expertise in the field, experience with international research coordination and a direct access to governments.[73] After an enthusiastic start on authority level, the German government reacted skeptically.[73] The initiative was seen as an American attempt[73] to regain international terrain after the lost Vietnam War. The topics and the internal coordination and preparation effort however gained momentum in civil conferences and institutions in Germany and beyond during the Brandt government.[73]

- 1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment,[73] leading role of Nobel Prize winner Willy Brandt and Olof Palme,[74] Germany saw enhanced international research cooperation on the greenhouse topic as necessary[73]

- 1978 Brandt Report, the greenhouse effect dealt with in the energy section[75]

- 1979: First World Climate Conference[76]

- 1987: Brundtland Report[75]

- 1987: Montreal Protocol on restricting ozone layer-damaging CFCs demonstrates the possibility of coordinated international action on global environmental issues.

- 1988: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change set up to coordinate scientific research, by two United Nations organizations, the World Meteorological Organization and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) to assess the "risk of human-induced climate change".

- 1992: United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change was formed to "prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system"

- 1996: European Union adopts target of a maximum 2 °C rise in average global temperature

- 25 June 1997: US Senate passes Byrd–Hagel Resolution rejecting Kyoto without more commitments from developing countries[72]

- 1997: Kyoto Protocol agreed

- 2001: George W. Bush withdraws from the Kyoto negotiations

- 16 February 2005: Kyoto Protocol comes into force (not including the US or Australia)

- 2005: the European Union Emissions Trading Scheme is launched, the first such scheme

- July 2005: 31st G8 summit has climate change on the agenda, but makes relatively little concrete progress

- November/December 2005: United Nations Climate Change Conference; the first meeting of the Parties of the Kyoto Protocol, alongside the 11th Conference of the Parties (COP11), to plan further measures for 2008–2012 and beyond.

- 30 October 2006: The Stern Review is published. It is the first comprehensive contribution to the global warming debate by an economist and its conclusions lead to the promise of urgent action by the UK government to further curb Europe's CO

2 emissions and engage other countries to do so. It discusses the consequences of climate change, mitigation measures to prevent it, possible adaptation measures to deal with its consequences, and prospects for international cooperation. - 26 June 2009: US House of Representatives passes the American Clean Energy and Security Act, the "first time either house of Congress had approved a bill meant to curb the heat-trapping gases scientists have linked to climate change."[77]

- 12 December 2015: World leaders meet in Paris, France for the 21st Conference of the Parties of the UNFCCC. One hundred eighty seven countries eventually signed on to the Paris Agreement. As of September 2016, 187 UNFCCC members have signed the treaty, 60 of which have ratified it. The agreement will only enter into force provided that 55 countries that produce at least 55% of the world's greenhouse gas emissions ratify, accept, approve or accede to the agreement; although the minimum number of ratifications has been reached, the ratifying states do not produce the requisite percentage of greenhouse gases for the agreement to enter into force.

- 1 June 2017: President Donald Trump withdraws the United States from the Paris Agreement

Political economy of climate change

Political economy of climate change is an approach that applies the political economy thinking of collective or political processes to study the critical issues surrounding the decision-making on climate change. The ever-increasing awareness and urgency of climate change have pressured scholars to explore a better understanding of the multiple actors and influencing factors that affect the climate change negotiation, and to seek more effective solutions to tackle climate change.[78] Climate Change is first and foremost a political issue now that it has become a widely believed fact.[79]

Background

Climate change and global warming have become one of the most pressing environmental concerns and the greatest global challenges in society today. As this issue continues to dominate the international agenda, researchers from different academic sectors have for long been devoting great efforts to explore effective solutions to climate change, with technologists and planners devising ways of mitigating and adapting to climate change; economists estimating the cost of climate change and the cost of tackling it; development experts exploring the impact of climate change on social services and public goods. However, Cammack (2007)[80] points out two problems with many of the above discussions, namely the disconnection between the proposed solutions to climate change from different disciplines; and the devoid of politics in addressing climate change at the local level. Further, the issue of climate change is facing various other challenges, such as the problem of elite-resource capture, the resource constraints in developing countries and the conflicts that frequently result from such constraints, which have often been less concerned and stressed in suggested solutions. In recognition of these problems, it is advocated that “understanding the political economy of climate change is vital to tackling it”.[80]

Meanwhile, the unequal distribution of the impacts of climate change and the resulting inequity and unfairness on the poor who contribute least to the problem have linked the issue of climate change with development study,[81][82] which has given rise to various programs and policies that aim at addressing climate change and promoting development.[83][84] Although great efforts have been made on international negotiations concerning the issue of climate change, it is argued that much of the theory, debate, evidence-gathering and implementation linking climate change and development assume a largely apolitical and linear policy process.[85] In this context, Tanner and Allouche (2011) suggest that climate change initiatives must explicitly recognize the political economy of their inputs, processes and outcomes so as to find a balance between effectiveness, efficiency and equity.[85]

Definition

In its earliest manifestations, the term “political economy” was basically a synonym of economics,[86] while it is now a rather elusive term that typically refers to the study of the collective or political processes through which public economic decisions are made.[87] In the climate change domain, Tanner and Allouche (2011) define the political economy as “the processes by which ideas, power and resources are conceptualized, negotiated and implemented by different groups at different scales”.[85] While there have emerged a substantial literature on the political economy of environmental policy, which explains the “political failure” of the environmental programmes to efficiently and effectively protect the environment,[87] systematic analysis on the specific issue of climate change using the political economy framework is relatively limited.

Characteristics of Climate Change

The urgent need to consider and understand the political economy of climate change is based on the specific characteristics of the problem.

The key issues include:

- The cross-sectoral nature of climate change: The issue of climate change usually fits into various sectors, which means that the integration of climate change policies into other policy areas is frequently called for.[88] Consequently, this has resulted in the highly complexity of the issue, as the problem needs to be addressed from multiple scales with diverse actors involved in the complex governance process.[89] The interaction of these facets leads to the political processes with multiple and overlapping conceptualizations, negotiation and governance issues, which requires the understanding of political economy processes.[85]

- The problematic perception of climate change as simply a “global” issue: Climate change initiatives and governance approaches have tended to be driven from a global scale. While the development of international agreements has witnessed a progressive step of global political action, this globally-led governance of climate change issue may be unable to provide adequate flexibility for specific national or sub-national conditions. Besides, from the development perspective of view, the issue of equity and global environmental justice would require a fair international regime within which the impact of climate change and poverty could be simultaneously prevented. In this context, climate change is not only a global crisis that needs the presence of international politics, but also a challenge for national or sub-national governments. The understanding of the political economy of climate change could explain the formulation and translation of international initiatives to specific national and sub-national policy context, which provides an important perspective to tackle climate change and achieve environmental justice.[85]

- The growth of climate change finance: Recent years have witnessed a growing number of financial flows and the development of financing mechanisms in the climate change arena. The 2010 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Cancun, Mexico has committed a significant amount of money from developed countries to developing a world in supportive of the adaptation and mitigation technologies. In short terms, the fast start finance will be transferred through various channels including bilateral and multilateral official development assistance, the Global Environment Facility, and the UNFCCC.[90] Besides, a growing number of public funds have provided greater incentives to tackle climate change in developing countries. For instance, the Pilot Program for Climate Resilience aims at creating an integrated and scaled-up approach of climate change adaptation in some low-income countries and preparing for future finance flows. In addition, climate change finance in developing countries could potentially change the traditional aid mechanisms, through the differential interpretations of ‘common but differentiated responsibilities’ by developing and developed countries.[91] Based on equity and climate justice, climate change resource flows are increasingly called on the developed world according to the culpability for damages.[92] As a result, it is inevitable to change the governance structures so as for developing countries to break the traditional donor-recipient relationships. Within these contexts, the understanding of the political economy processes of financial flows in the climate change arena would be crucial to effectively govern the resource transfer and to tackling climate change.[85]

- Different ideological worldviews of responding to climate change: Nowadays, because of the perception of science as a dominant policy driver, much of the policy prescription and action in climate change arena have concentrated on assumptions around standardized governance and planning systems, linear policy processes, readily transferable technology, economic rationality, and the ability of science and technology to overcome resource gaps.[93] As a result, there tends to be a bias towards technology-led and managerial approaches to address climate change in apolitical terms. Besides, a wide range of different ideological worldviews would lead to a high divergence of the perception of climate change solutions, which also has a great influence on decisions made in response to climate change.[94] Exploring these issues from a political economy perspective provides the opportunity to better understand the “complexity of politic and decision-making processes in tackling climate change, the power relations mediating competing claims over resources, and the contextual conditions for enabling the adoption of technology”.[85]

- Unintended negative consequences of adaptation policies that fail to factor in environmental-economic trade-offs: Successful adaptation to climate change requires balancing competing economic, social, and political interests. In the absence of such balancing, harmful unintended consequences can undo the benefits of adaptation initiatives. For example, efforts to protect coral reefs in Tanzania forced local villagers to shift from traditional fishing activities to farming that produced higher greenhouse gas emissions.[95]

Socio-political Constraints

The role of political economy in understanding and tackling climate change is also founded upon the key issues surrounding the domestic socio-political constraints:[80]

- The problems of fragile states: Fragile states—defined as poor performers, conflict and/or post-conflict states—are usually incapable of using the aid for climate change effectively. The issues of power and social equity have exacerbated the climate change impacts, while insufficient attention has been paid to the dysfunction of fragile states. Considering the problems of fragile states, the political economy approach could improve the understanding of the long-standing constraints upon capacity and resilience, through which the problems associated with weak capacity, state-building and conflicts could be better addressed in the context of climate change.

- Informal governance: In many poorly performing states, decision-making around the distribution and use of state resources is driven by informal relations and private incentives rather than formal state institutions that are based on equity and law. This informal governance nature that underlies in the domestic social structures prevents the political systems and structures from rational functioning and thus hinders the effective response towards climate change. Therefore, domestic institutions and incentives are critical to the adoption of reforms. The political economy analysis provides an insight into the underlying social structures and systems that determine the effectiveness of climate change initiatives (1).

- The difficulty of social change: Developmental change in underdeveloped countries is painfully slow because of a series of long-term collective problems, including the societies’ incapacity of working collectively to improve wellbeing, the lack of technical and social ingenuity, the resistance and rejection to innovation and change. In the context of climate change, these problems significantly hinder the promotion of climate change agenda. Taking a political economy view in the underdeveloped countries could help to understand and create incentives to promote transformation and development, which lays a foundation for the expectation of implementing a climate change adaptation agenda.

Research focuses and approaches

Brandt and Svendsen (2003)[96] introduce a political economy framework that based on the political support function model by Hillman (1982)[97] into the analysis of the choice of instruments to control climate change in the European Union policy to implement its Kyoto Protocol target level. In this political economy framework, the climate change policy is determined by the relative strength of stakeholder groups. By examining the different objective of different interest groups, namely industry groups, consumer groups and environmental groups, the authors explain the complex interaction between the choices of an instrument for the EU climate change policy, specifically the shift from the green taxation to a grandfathered permit system.

A report by the Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) (2011) takes a political economy approach to explain why some countries adopt climate change policies while others do not, specifically among the countries in the transition region.[98] This work analyzes the different political economy aspects of the characteristics of climate change policies so as to understand the likely factors driving climate change mitigation outcomes in many transition countries. The main conclusions are listed below:

- The level of democracy alone is not a major driver of climate change policy adoption, which means that the expectations of contribution to global climate change mitigation are not necessarily limited by the political regime of a given country.

- Public knowledge, shaped by various factors including the threat of climate change in a particular country, the national level of education and existence of free media, is a critical element in climate change policy adoption, as countries with the public more aware of the climate change causes are significantly more likely to adopt climate change policies. The focus should, therefore, be on promoting public awareness of the urgent threat of climate change and prevent information asymmetries in many transition countries.

- The relative strength of the carbon-intensive industry is a major deterrent to the adoption of climate change policies, as it partly accounts for the information asymmetries. However, the carbon-intensive industries often influence government's decision-making on climate change policy, which thus calls for a change of the incentives perceived by these industries and a transition of them to a low-carbon production pattern. Efficient means include the energy price reform and the introduction of international carbon trading mechanisms.

- The competitive edge gained national economies in the transition region in a global economy, where increasing international pressure is put to reduce emissions, would enhance their political regime's domestic legitimacy, which could help to address the inherent economic weaknesses underlying the lack of economic diversification and global economic crisis.

Tanner and Allouche (2011)[85] propose a new conceptual and methodological framework for analyzing the political economy of climate change in their latest work, which focuses on the climate change policy processes and outcomes in terms of ideas, power and resources. The new political economy approach is expected to go beyond the dominant political economy tools formulated by international development agencies to analyse climate change initiatives[99][100][101] that have ignored the way that ideas and ideologies determine the policy outcomes (see table).[102] The authors assume that each of the three lenses, namely ideas, power and resources, tends to be predominant at one stage of the policy process of the political economy of climate change, with “ideas and ideologies predominant in the conceptualisation phase, power in the negotiation phase and resource, institutional capacity and governance in the implementation phase”.[85] It is argued that these elements are critical in the formulation of international climate change initiatives and their translation to national and sub-national policy context.

| Issue | Dominant approach | New political economy |

|---|---|---|

| Policy process | Linear, informed by evidence | Complex, informed by ideology, actors and power relations |

| Dominant scale | Global and inter-state | Translation of international to national and sub-national level |

| Climate change science and research | Role of objective science in informing policy | Social construction of science and driving narratives |

| Scarcity and poverty | Distributional outcomes | Political processes mediating competing claims for resources |

| Decision-making | Collective action, rational choice and rent seeking | Ideological drivers and incentives, power relations |

See also

Specific meetings and groups

General topics

- Business action on climate change

- Carbon emission trading

- Carbon footprint

- Carbon leakage

- Climate action

- Climate change denial

- Climate change policy of the United States

- Climate movement

- Clean Development Mechanism

- Climate legislation

- Copenhagen Accord

- Economics of global warming

- Environmental agreements

- Environmental impact of aviation

- Environmental law

- Environmental politics

- Environmental tariff

- List of climate change initiatives

- List of international environmental agreements

- Low-carbon economy

- Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation or REDD

- Sustainability

References

- Borenstein, Seth (29 November 2015). "Earth is a wilder, warmer place since last climate deal made". Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- ""Voices" speaker talks climate change". The Dartmouth. Archived from the original on 24 March 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- Westervelt, Amy (7 August 2020). "Fossil Fuel Companies Are Lobbying Hard for Protection from Coronavirus-related Lawsuits by Workers". Drilled News. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- Vesa, Juho; Gronow, Antti; Ylä-Anttila, Tuomas (1 July 2020). "The quiet opposition: How the pro-economy lobby influences climate policy". Global Environmental Change. 63: 102117. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102117. ISSN 0959-3780.

- Clark, Peter U.; Shakun, Jeremy D.; Marcott, Shaun A.; Mix, Alan C.; Eby, Michael; Kulp, Scott; Levermann, Anders; Milne, Glenn A.; Pfister, Patrik L.; Santer, Benjamin D.; Schrag, Daniel P. (8 February 2016). "Consequences of twenty-first-century policy for multi-millennial climate and sea-level change". Nature Climate Change. 6 (4): 360–369. Bibcode:2016NatCC...6..360C. doi:10.1038/nclimate2923. ISSN 1758-6798.

- "Arsenic poisoning stalks India's gold mines". SciDev.

- "World Energy Balances – Analysis". IEA. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- Friedlingstein et al. 2019, Table 7.

- Global Energy Review in 2011, Enerdata Publication

- Landale, James (3 January 2020). "How the end of oil could destabilise geopolitics". Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- "Green cement? Captured carbon may fuel new markets and help climate". Reuters. 7 November 2019. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- Vidal, John (3 December 2012). "Climate change compensation emerges as major issue at Doha talks". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- The Guardian (UK), 17 Sept. 2019 "The Silenced: Meet The Climate Whistleblowers Muzzled by Trump--Six whistleblowers and ex-government scientists describe how the Trump administration made them bury climate science – and why they won’t stay quiet"

- Union of Concerned Scientists, "Abuses of Science: Case Studies, Examples of Political Interference with Government Science Documented by The UCS Scientific Integrity Program, 2004-2009"

- National Center for Science Education, "Review: The Republican War on Science, Reports of the National Center for Science Education"

- Climate Science and Policy Watch, "Climate Science Censorship"

- The Nation, 17 Sept. 2019, "Climate Whistle-Blowers Muzzled by Trump: Six Former Government Scientists Describe How the Trump Administration Made Them Bury the Truth about Climate Change—and Why They Won’t Stay Quiet"

- The Guardian, 24 Sept. 2019, "Revealed: How the FBI Targeted Environmental Activists in Domestic Terror Investigations: Protesters Were Characterized as a Threat to National Security in What One Calls an Attempt to Criminalize their Actions"

- Dessai 2001, p. 5

- "Ratification Tracker". Climate Analytics. Archived from the original on 24 July 2018. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- "Global Climate Action NAZCA". Global Climate Action Portal. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- "global climate action portal NAZCA, About". global climate action portal NAZCA. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- "As Economic Concerns Recede, Environmental Protection Rises on the Public's Policy Agenda / Partisan gap on dealing with climate change gets even wider". PewResearch.org. Pew Research Center. 13 February 2020. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021.

- Garmann, Sebastian (2014). "Do government ideology and fragmentation matter for reducing CO2-emissions? Empirical evidence from OECD countries". Ecological Economics. 105: 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.05.011. ISSN 0921-8009.

- Sauerbrey, Anna (18 April 2019). "Opinion | How Climate Became Germany's New Culture War". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- "Landmark ruling that Holland must curb emissions to protect citizens from climate emergency upheld". The Independent. 21 December 2019. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- Shearer, Christine; Myllyvirta, Lauri; Yu, Aiqun; Aitken, Greig; Mathew-Shah, Neha; Dallos, Gyorgy; Nace, Ted (March 2020). Boom and Bust 2020: Tracking the Global Coal Plant Pipeline (PDF) (Report). Global Energy Monitor.

- "C40 Knowledge Community". www.c40knowledgehub.org. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- "Reports". imf.org. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- "Phasing out fossil fuels". euronews.com. 15 November 2019. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- "How Reforming Fossil Fuel Subsidies Can Go Wrong: A lesson from Ecuador". IISD. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- "Solving the coal puzzle: Lessons from four years of coal phase-out policy in Europe" (PDF).

- "China announced new climate goals. But it can't quit coal just yet". Washington Post.

- "Coal's Last Refuge Crumbles With China's Renewables Plan". www.bloomberg.com. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- "NEXT: The Politics of Trees". ColumbusUnderground.com. 13 August 2019. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- David Michaels (2008) Doubt is Their Product: How Industry's Assault on Science Threatens Your Health.

- Hoggan, James; Littlemore, Richard (2009). Climate Cover-Up: The Crusade to Deny Global Warming. Vancouver: Greystone Books. ISBN 978-1-55365-485-8. Retrieved 19 March 2010. See, e.g., p31 ff, describing industry-based advocacy strategies in the context of climate change denial, and p73 ff, describing involvement of free-market think tanks in climate-change denial.

- Coren, Michael J. "Oil companies and utilities are buying up all the electric car charging startups". Quartz. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- "Enron Sought Global Warming Regulation, Not Free Markets". Competitive Enterprise Institute. Archived from the original on 21 September 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- "How Climate Change in Iowa is Changing U.S. Politics". Time. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- "Political will is the most important driver of climate-neutral agriculture". D+C. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- "The CAP and climate change". European Commission - European Commission. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- "Banking on carbon trading: Can banks stop climate change?". CNN. 20 July 2008. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- "The climate lobby from soup to nuts". Center for Public Integrity. 27 December 2009. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- "Under Obama, Spain's Solar, Wind Energy Companies Invest Big In US". Huffington Post. 18 January 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- "The inclusive route to low-carbon electricity : Energy & Environment - World Nuclear News". www.world-nuclear-news.org. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- Nhede, Nicholas (10 April 2019). "DSOs as key actors in e-mobility". Smart Energy International. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- "25 Big Companies That Are Going Green". Business Pundit. 29 July 2008. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- Shindell D, Faluvegi G, Seltzer K, Shindell C (2018). "Quantified, Localized Health Benefits of Accelerated Carbon Dioxide Emissions Reductions". Nat Clim Chang. 8 (4): 291–295. Bibcode:2018NatCC...8..291S. doi:10.1038/s41558-018-0108-y. PMC 5880221. PMID 29623109.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "How ICTs can tackle the climate crisis". www.telecomreview.com. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- "Climate change lobbying dominated by 10 firms". Politico. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- "Greenpeace informal alliance with Wind and Solar". Retrieved 23 February 2013.

-

Oreskes, Naomi (December 2004). "BEYOND THE IVORY TOWER: The Scientific Consensus on Climate Change". Science. 306 (5702): 1686. doi:10.1126/science.1103618. PMID 15576594.

Such statements suggest that there might be substantive disagreement in the scientific community about the reality of anthropogenic climate change. This is not the case. [...] Politicians, economists, journalists, and others may have the impression of confusion, disagreement, or discord among climate scientists, but that impression is incorrect.

-

America's Climate Choices: Panel on Advancing the Science of Climate Change; National Research Council (2010). Advancing the Science of Climate Change. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/12782. ISBN 978-0-309-14588-6. Archived from the original on 29 May 2014.

(p1) ... there is a strong, credible body of evidence, based on multiple lines of research, documenting that climate is changing and that these changes are in large part caused by human activities. While much remains to be learned, the core phenomenon, scientific questions, and hypotheses have been examined thoroughly and have stood firm in the face of serious scientific debate and careful evaluation of alternative explanations. * * * (p21-22) Some scientific conclusions or theories have been so thoroughly examined and tested, and supported by so many independent observations and results, that their likelihood of subsequently being found to be wrong is vanishingly small. Such conclusions and theories are then regarded as settled facts. This is the case for the conclusions that the Earth system is warming and that much of this warming is very likely due to human activities.

CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) -

"Understanding and Responding to Climate Change" (PDF). United States National Academy of Sciences. 2008. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

Most scientists agree that the warming in recent decades has been caused primarily by human activities that have increased the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

- American Association for the Advancement of Science Statement on the Teaching of Evolution Archived 21 February 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Intelligent Judging—Evolution in the Classroom and the Courtroom George J. Annas, New England Journal of Medicine, Volume 354:2277-2281 25 May 2006

- Oreskes, Naomi; Conway, Erik (25 May 2010). Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obsecured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming (first ed.). Bloomsbury Press. ISBN 978-1-59691-610-4.

- Boykoff, M.T.; Boykoff, J.M. (2004). "Balance as bias: Global warming and the US prestige press". Global Environmental Change. 14 (2): 125–136. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2003.10.001.

- Technische Problemlösung, Verhandeln und umfassende Problemlösung, (eng. technical trouble shooting, negotiating and generic problem solving capability) in Gesellschaftliche Komplexität und kollektive Handlungsfähigkeit (Societys complexity and collective ability to act), ed. Schimank, U. (2000). Frankfurt/Main: Campus, p.154-182 book summary at the Max Planck Gesellschaft Archived 12 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Of Montreal and Kyoto: A Tale of Two Protocols by Cass R. Sunstein 38 ELR 10566 8/2008

- Aant Elzinga, "Shaping Worldwide Consensus: the Orchestration of Global Change Research", in Elzinga & Landström eds. (1996): 223-255. ISBN 0-947568-67-0.

- Climate Change: What Role for Sociology? A Response to Constance Lever-Tracy, Reiner Grundmann and Nico Stehr, doi: 10.1177/0011392110376031 Current Sociology November 2010 vol. 58 no. 6 897-910, see Lever Tracys paper in the same journal Archived 29 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Environmental Politics Climate Change and Knowledge Politics REINER GRUNDMANN Vol. 16, No. 3, 414–432, June 2007 Archived 26 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Ungar, Sheldon (July 2000). "Knowledge, ignorance and the popular culture: climate change versus the ozone hole, by Sheldon Ungar". Public Understanding of Science. 9 (3): 297–312. doi:10.1088/0963-6625/9/3/306. S2CID 7089937.

- Michael Oppenheimer et al., The limits of consensus, in Science Magazine's State of the Planet 2008-2009: with a Special Section on Energy and Sustainability, Donald Kennedy, Island Press, 01.12.2008, separate as CLIMATE CHANGE, The Limits of Consensus Michael Oppenheimer, Brian C. O'Neill, Mort Webster, Shardul Agrawal, in Science 14 September 2007: Vol. 317 no. 5844 pp. 1505-1506 DOI: 10.1126/science.1144831

- Overland, Indra; Sovacool, Benjamin K. (1 April 2020). "The misallocation of climate research funding". Energy Research & Social Science. 62: 101349. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2019.101349. ISSN 2214-6296.

- "Where in the world do people emit the most CO2?". Our World in Data. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- How Margaret Thatcher Made the Conservative Case for Climate Action, James West, Mother Jones, Mon 8 Apr. 2013

- An Inconvenient Truth About Margaret Thatcher: She Was a Climate Hawk, Will Oremus, Slate (magazine) 8 April 2013

- IPCC 1995. Second Assessment Report: Climate change 1995

- "Byrd-Hagel Resolution (S. Res. 98) Expressing the Sense of the Senate Regarding Conditions for the US Signing the Global Climate Change Treaty". Nationalcenter.org. Archived from the original on 2 November 2006. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- Die Frühgeschichte der globalen Umweltkrise und die Formierung der deutschen Umweltpolitik(1950-1973) (Early history of the environmental crisis and the setup of German environmental policy 1950-1973), Kai F. Hünemörder, Franz Steiner Verlag, 2004 ISBN 3-515-08188-7

- A "Scandinavian connection" was alleged by Nils-Axel Mörner who saw an early friendship of Palme and Bert Bolin as reasons for Bolin then being promoted as environmental steward in the Swedish government and later as first head of the IPCC

- "The Brandt Proposals: A Report Card, Energy and the Environment". Archived from the original on 18 January 2009. Retrieved 24 December 2008.

- "The First World Climate Conference". Archived from the original on 28 September 2007.

- Broder, John (26 June 2009). "House Passes Bill to Address Threat of Climate Change". New York Times. Retrieved 27 June 2009.

- Dietz, Thomas (9 July 2020). "Political events and public views on climate change". Climatic Change. 161 (1): 1–8. Bibcode:2020ClCh..161....1D. doi:10.1007/s10584-020-02791-6. ISSN 0165-0009. PMC 7347262. PMID 32836574.

- Kamarck, Elaine (23 September 2019). "The challenging politics of climate change". Brookings. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- Cammack, D. (2007) Understanding the political economy of climate change is vital to tackling it, Prepared by the Overseas Development Institute for UN Climate Change Conference in Bali, December 2007.

- Adger, W.N., Paavola, Y., Huq, S. and Mace, M.J. (2006) Fairness in Adaptation to Climate Change, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Tol, R.S.J.; Downing, T.E.; Kuik, O.J.; Smith, J.B. (2004). "Distributional Aspects of Climate Change Impacts". Global Environmental Change. 14 (3): 259–72. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.175.5563. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2004.04.007.

- IEA, UNDP and UNIDO (2010) Energy Poverty: How to Make Modern Energy Access Universal?, special early excerpt of the World Energy Outlook 2010 for the UN General Assembly on the Millennium Development Goals, Paris: OECD/IEA.

- Nabuurs, G.J., Masera, O., Andrasko, K., Benitez-Ponce, P., Boer, R., Dutschke, M., Elsiddig, E., Ford-Robertson, J., Frumhoff, P., Karjalainen, T., Krankina, O., Kurz, W.A., Matsumoto, M., Oyhantcabal, W., Ravindranath, N.H., Sanz Sanchez, M.J. and Zhang, X. (2007) ‘Forestry’, in: Mitigation of Climate Change, Contribution of Working Group III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- 6. Tanner, T. and Allouche, J. (2011) 'Towards a New Political Economy of Climate Change and Development', IDS Bulletin Special Issue: Political Economy of Climate Change, 42(3): 1-14.

- Groenewegen, E.(1987) 'Political economy and economics', in: Eatwell J. et al., eds., The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, Vol.3: 904-907, Macmillan & Co., London.

- Oates, W.E.and Portney, P.R.(2003) 'The political economy of environmental policy', in: Handbook of Environmental Economics, chapter 08: p325-54

- OECD (2009) Policy Guidance on Integrating Climate Change Adaptation into Development Co-operation, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris.

- Rabe, B.G. (2007). "Beyond Kyoto: Climate Change Policy in Multilevel Governance Systems". Governance. 20 (3): 423–44. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0491.2007.00365.x.

- Harmeling, S. and Kaloga, A. (2011)'Understanding the Political Economy of the Adaptation Fund', IDS Bulletin Special Issue: Political Economy of Climate Change, 42(3): 23-32

- Okereke, C (2008). "Equity Norms in Global Environmental Governance". Global Environmental Politics. 8 (3): 25–50. doi:10.1162/glep.2008.8.3.25. S2CID 57569481.

- Abdullah, A., Muyungi, R., Jallow, B., Reazuddin, M. and Konate, M. (2009) National Adaptation Funding: Ways Forward for the Poorest Countries, IIED Briefing Paper, International Institute for Environment and Development, London.

- Leach, M., Scoones, I. and Stirling, A. (2010), Dynamic Sustainabilities–Technology, Environment, Social Justice, London: Earthscan.

- Carvalho, A (2007). "Ideological Cultures and Media Discourses on Scientific Knowledge: Re-reading News on Climate Chang". Public Understanding of Science. 16 (2): 223–43. doi:10.1177/0963662506066775. hdl:1822/41838.

- Editorial (November 2015). "Adaptation trade-offs". Nature Climate Change. 5 (11): 957. Bibcode:2015NatCC...5Q.957.. doi:10.1038/nclimate2853. See also Sovacool, B. and Linnér, B.-O. (2016), The Political Economy of Climate Change Adaptation, Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Brandt, U.S. and Svendsen, G.T. (2003) The Political Economy of Climate Change Policy in the EU: Auction and Grandfathering, IME Working Papers No. 51/03.

- Hillman, A.L. (1982). "Declining industries and political-support protec-tionist motives". The American Economic Review. 72 (5): 1180–7. JSTOR 1812033.

- EBRD (2011) 'Political economy of climate change policy in the transition region', in: Special Report on Climate Change: The Low Carbon Transition, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, Chapter Four.

- DFID (2009) Political Economy Analysis: How to Note, DFID Practice Paper, Department for International Development, London.

- World Bank (2009) Problem-Driven Governance and Political Economy Analysis: Good Practice Framework, World Bank, Washington D.C.

- World Bank (2004) Operationalizing Political Analysis: The Expected Utility Stakeholder Model and Governance Reforms, PREM Notes 95, World Bank, Washington D.C.

- Barnett, M.N. and Finnemore, M. (2004) Rules for the World: International Organizations in Global Politics, Cornell University Press, New York.

Further reading

- Naomi Klein (2019). On Fire: The Burning Case for a Green New Deal, Allen Lane, ISBN 978-0241410721.

External links

Environmental groups

- Panda—the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF)

- Greenpeace—Greenpeace

- Stop Climate Chaos—Coalition of UK charities

Business

- Carbon Disclosure Project Carbon Disclosure Project , supported by over 150 institutional investors, aims for transparency on companies' greenhouse gas emissions