Battle of North Anna

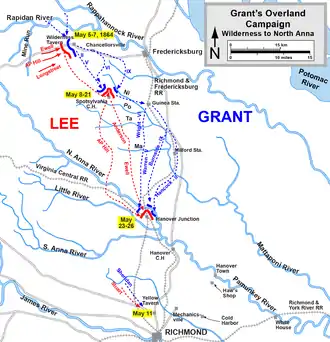

The Battle of North Anna was fought May 23–26, 1864, as part of Union Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant's Overland Campaign against Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. It consisted of a series of small actions near the North Anna River in central Virginia, rather than a general engagement between the armies. The individual actions are sometimes separately known as: Telegraph Road Bridge and Jericho Mills (for actions on May 23); Ox Ford, Quarles Mill, and Hanover Junction (May 24).

| Battle of North Anna | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

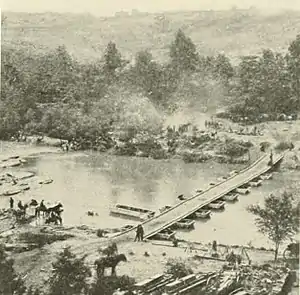

Pontoon bridge constructed by Union engineers for crossing the North Anna River | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Ulysses S. Grant George G. Meade | Robert E. Lee | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Army of Northern Virginia | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 67,000–100,000[2] | 50,000–53,000[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

3,986 total (591 killed; 2,734 wounded; 661 captured/missing)[3][4] |

1,552 (124 killed, 704 wounded, 724 missing/captured)[5] | ||||||

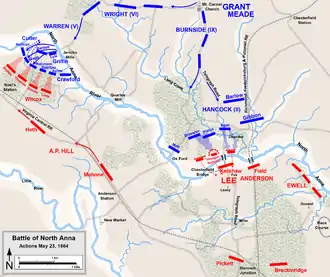

After disengaging from the stalemate at Spotsylvania Court House, Grant moved his army to the southeast, hoping to lure Lee into battle on open ground. He lost the race to Lee's next defensive position south of the North Anna River, but Lee was unsure of Grant's intention and initially prepared no significant defensive works. On May 23, the Union V Corps under Maj. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren forded the river at Jericho Mills and a Confederate division from the corps of Lt. Gen. A.P. Hill was unable to dislodge its beachhead. The II Corps under Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock stormed a small Confederate force at "Henagan's Redoubt" to seize the Chesterfield Bridge crossing on the Telegraph Road, but did not advance further south across the river.

That night, Lee and his engineers devised a scheme for defensive earthworks in the shape of an inverted "V" that could split the Union army when it advanced and allow the Confederates to use interior lines to attack and defeat one wing, preventing the other wing from reinforcing it in time. The Union army initially fell into this trap. As Hancock's men failed to carry the Confederate works on the eastern leg of the V on May 24, a brigade under the drunken Brig. Gen. James H. Ledlie was repulsed from an ill-conceived assault against a strong position at Ox Ford, the apex of the V. Unfortunately for the Confederates, Lee was disabled with an intestinal illness and none of his subordinates were able to execute his planned attack.

After two days of skirmishing in which the armies stared at each other from their earthworks, the inconclusive battle ended when Grant ordered another wide movement to the southeast, in the direction of the crossroads at Cold Harbor.

Background

Grant's Overland Campaign was one of a series of simultaneous offensives the newly appointed general in chief launched against the Confederacy. By late May 1864, only two of these continued to advance: Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman's Atlanta Campaign and the Overland Campaign, in which Grant accompanied and directly supervised the Army of the Potomac and its commander, Maj. Gen. George G. Meade. Grant's campaign objective was not the Confederate capital of Richmond, but the destruction of Lee's army. President Abraham Lincoln had long advocated this strategy for his generals, recognizing that the city would certainly fall after the loss of its principal defensive army. Grant ordered Meade, "Wherever Lee goes, there you will go also."[6] Although he hoped for a quick, decisive battle, Grant was prepared to fight a war of attrition. Both Union and Confederate casualties could be high, but the Union had greater resources to replace lost soldiers and equipment.[7]

On May 5, after Grant's army crossed the Rapidan River and entered the Wilderness of Spotsylvania, it was attacked by Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. Although Lee was outnumbered, about 60,000 to 100,000, his men fought fiercely and the dense foliage provided a terrain advantage. After two days of fighting and almost 29,000 casualties, the results were inconclusive and neither army was able to obtain an advantage. Lee had stopped Grant, but had not turned him back; Grant had not destroyed Lee's army. Under similar circumstances, previous Union commanders had chosen to withdraw behind the Rappahannock, but Grant instead ordered Meade to move around Lee's right flank and seize the important crossroads at Spotsylvania Court House to the southeast, hoping that by interposing his army between Lee and Richmond, he could lure the Confederates into another battle on a more favorable field.[8]

Elements of Lee's army beat the Union army to the critical crossroads of Spotsylvania Court House and began entrenching. Meade was dissatisfied with Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan's Union cavalry's performance and released it from its reconnaissance and screening duties for the main body of the army to pursue and defeat the Confederate cavalry under Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart. Sheridan's men mortally wounded Stuart in the tactically inconclusive Battle of Yellow Tavern (May 11) and then continued their raid toward Richmond, leaving Grant and Meade without the "eyes and ears" of their cavalry.[9]

Near Spotsylvania Court House, fighting occurred on and off from May 8 through May 21, as Grant tried various schemes to break the Confederate line. On May 8, Union Maj. Gens. Gouverneur K. Warren and John Sedgwick unsuccessfully attempted to dislodge the Confederates under Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson from Laurel Hill, a position that was blocking them from Spotsylvania Court House. On May 10, Grant ordered attacks across the Confederate line of earthworks, which by now extended over 4 miles (6.5 km), including a prominent salient known as the Mule Shoe. Although the Union troops failed again at Laurel Hill, an innovative assault attempt by Col. Emory Upton against the Mule Shoe showed promise.[10]

Grant used Upton's assault technique on a much larger scale on May 12 when he ordered the 15,000 men of Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock's corps to assault the Mule Shoe. Hancock was initially successful, but the Confederate leadership rallied and repulsed his incursion. Attacks by Maj. Gen. Horatio G. Wright on the western edge of the Mule Shoe, which became known as the "Bloody Angle," involved almost 24 hours of desperate hand-to-hand fighting, some of the most intense of the Civil War. Supporting attacks by Warren and by Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside were unsuccessful.[11]

Grant repositioned his lines in another attempt to engage Lee under more favorable conditions and launched a final attack by Hancock on May 18, which made no progress. A reconnaissance in force by Confederate Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell at Harris farm on May 19 was a costly and pointless failure. In the end, the battle was tactically inconclusive, but with almost 32,000 casualties on both sides, it was the costliest battle of the campaign. Grant planned to end the stalemate by once again shifting around Lee's right flank to the southeast, toward Richmond.[12]

Opposing forces

Union

Grant's Union forces totaled approximately 68,000 men, depleted from the start of the campaign by battle losses, illnesses, and expired enlistments.[2] They consisted of the Army of the Potomac, under Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, and the IX Corps (until May 24 formally part of the Army of the Ohio, reporting directly to Grant, not Meade). The five corps were:[13]

- II Corps, under Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock, including the divisions of Maj. Gen. David B. Birney and Brig. Gens. Francis C. Barlow, John Gibbon, and Robert O. Tyler.

- V Corps, under Maj. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren, including the divisions of Brig. Gens. Charles Griffin, Samuel W. Crawford, and Lysander Cutler.

- VI Corps, under Brig. Gen. Horatio G. Wright, including the divisions of Brig. Gens. David A. Russell, Thomas H. Neill, and James B. Ricketts.

- IX Corps, under Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside, including the divisions of Maj. Gen. Thomas L. Crittenden and Brig. Gens.Robert B. Potter, Orlando B. Willcox, and Edward Ferrero.

- Cavalry Corps, under Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan, including the divisions of Brig. Gens. Alfred T.A. Torbert, David McM. Gregg, and James H. Wilson. (During the period of May 9–24, Sheridan's Cavalry Corps was absent on detached duty and took no part in the operations around Spotsylvania Court House or the North Anna River.)

Confederate

Lee's Confederate Army of Northern Virginia comprised about 53,000 men[2] and was organized into four corps:[14]

- First Corps, under Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson, including the divisions of Maj. Gens. Charles W. Field and George E. Pickett, and Brig. Gen. Joseph B. Kershaw. (Three of Pickett's four brigades returned to the Army of Northern Virginia May 21–23 from duty at the James River.)

- Second Corps, under Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell, including the divisions of Maj. Gens. Jubal A. Early and Robert E. Rodes. (Jubal Early was temporary commander of the Third Corps until May 21; during this assignment, his Second Corps division was commanded by Maj. Gen. John B. Gordon. Gordon then was given command of two brigades that had earlier been in the division of Maj. Gen. Edward "Allegheny" Johnson, who was captured by Union troops at Spotsylvania Court House on May 12.)

- Third Corps, under Lt. Gen. A.P. Hill, including the divisions of Maj. Gens. Henry Heth, John C. Breckinridge, and Cadmus M. Wilcox, and Brig. Gen. William Mahone. (Hill returned from sick leave on May 21. Breckinridge's Division joined the army on May 22 from duty in the Shenandoah Valley.)

- Cavalry Corps, without a commander following the mortal wounding of Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart on May 11, including the divisions of Maj. Gens. Wade Hampton, Fitzhugh Lee, and W.H.F. "Rooney" Lee. (Hampton became the commander of the Cavalry Corps on August 11, 1864.)

For the first time in the campaign, Lee received sizable reinforcements, including three of the four brigades in Maj. Gen. George E. Pickett's division (about 6,000 men) from the James River defense against the ineffective Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler and two brigades (2,500 men) of Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge's command from the Shenandoah Valley. Pickett's men arrived May 21–23, Breckinridge was assigned temporarily to Lee beginning May 20 at Hanover Junction.[15]

Initial movements

May 21–23: Maneuvers to the North Anna

Grant's objective following Spotsylvania was the North Anna River, about 25 miles (40 km) south, and the important railroad intersection just south of it, Hanover Junction (the modern village of Doswell, Virginia). By seizing both of these, Grant could not only interrupt Lee's supply line, he could deny the Confederates their next logical defensive line, forcing them to attack his army in the open, under more favorable terms. Grant knew that Lee could probably beat him in a straight race to the North Anna, so he devised a stratagem that might be a successful alternative. He designated Hancock's II Corps to head southeast from Spotsylvania to Milford Station, hoping that Lee would take the bait and attack this isolated corps. If he did, Grant would attack him with his three remaining corps; if he did not, Grant would have lost nothing and his advance element might reach the North Anna before Lee could.[16]

Hancock's corps of 20,000 men started marching the night of May 20–21, screened by three regiments of Union cavalry under Brig. Gen. Alfred T.A. Torbert, who skirmished with their Confederate counterparts led by Brig. Gen. John R. Chambliss. By dawn on May 21 they reached Guinea Station,[17] where a number of the Union soldiers visited the Chandler house, the site of Stonewall Jackson's death a year earlier. The Union cavalry, riding out ahead, encountered 500 soldiers from Maj. Gen. George E. Pickett's division, which was marching north from Richmond to join Lee's army. After a brief skirmish, the Confederates withdrew across the Mattaponi River to the west of Milford Station, but the 11th Virginia Infantry did not receive the order and was forced to surrender. Hancock had expected to encounter soldiers from Lee's main army, so he was surprised to find Pickett's men at Milford Station, from which he inferred correctly that Lee was being reinforced. Rather than risk his corps in a fight in an isolated location, he decided to terminate his maneuver.[18]

By the afternoon of May 21, Lee was still in the dark about Grant's intentions and was reluctant to disengage prematurely from the Spotsylvania Court House line. He cautiously extended Ewell's Corps to the Telegraph Road (current day U.S. Route 1). He also notified Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge, who had just defeated a small Union army in the Shenandoah Valley and was en route to join Lee, to stop at Hanover Junction and defend the North Anna River line until Lee could join him. Meanwhile, Grant started the rest of his corps on their marches. As Warren's V Corps began marching toward Massaponax Church, Grant received intelligence about Ewell's Corps blocking the Telegraph Road and changed Warren's orders to proceed instead to Guinea Station and follow Hancock's corps. Burnside's IX Corps encountered Ewell's men on the Telegraph Road and Burnside ordered them to turn around and proceed to Guinea Station. Wright's VI Corps then followed Burnside. By this time, Lee had a clear picture of Grant's plan and he ordered Ewell to march south on the Telegraph Road, followed by Anderson's Corps, and A.P. Hill's Corps on parallel roads to the west. Lee's orders were not urgent—he knew that Ewell had 25 miles (40 km) to march over relatively good roads, versus Hancock's 34 miles (55 km) over inferior roads.[19]

May 21 was a day of missed opportunities for Grant. Lee failed to take the bait of the isolated II Corps and instead marched by the most direct route to the North Anna. That night, Warren's V Corps bivouacked a mile east of the Telegraph Road and somehow managed to miss Lee's army marching south right next to it. If Warren had attacked Lee's flank, he could have inflicted significant damage to the Confederate army. Instead, Lee's army reached the North Anna unmolested on May 22. Grant realized that Lee had beaten him to his objective and decided to give his exhausted men an easier day on the march, following Lee down the Telegraph Road for only a few miles before resting for the night.[20]

Battle

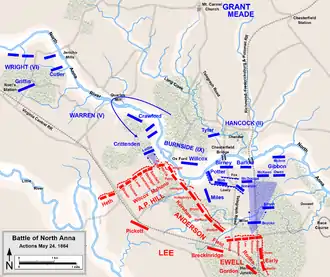

May 23: Chesterfield Bridge and Jericho Mills

On the morning of May 23, Warren reached Mount Carmel Church and paused for instructions. Hancock's corps came up from behind and the two units got hopelessly mixed up on the road. The corps commanders decided that Hancock would continue along the Telegraph Road to Chesterfield Bridge while Warren would cross the North Anna upstream at Jericho Mills. There were no significant fortifications to their front. Lee had misjudged Grant's plan, assuming that any advance against the North Anna would be a mere diversion, while the main body of Grant's army continued its flanking march to the east. At the Chesterfield Bridge crossing the Telegraph Road, a small South Carolina brigade under Col. John W. Henagan had created a dirt redoubt, and there was a small party guarding the railroad bridge downstream, but all of the other river crossings were left undefended. Grant had been presented with a golden opportunity if he moved quickly enough to take advantage of it.[21]

The division of Maj. Gen. David B. Birney led Hancock's column on the Telegraph Road. As they began to take fire from Henagan's Redoubt, Birney deployed two brigades to attack: Brig. Gen. Thomas W. Egan's brigade east of the road and Brig. Gen. Byron R. Pierce's brigade to the west. The II Corps artillery opened fire on the Confederates and Col. Edward Porter Alexander's First Corps artillery returned fire. General Lee, observing at the Fox house, was nearly hit by a cannonball that lodged in a door frame. Alexander was almost killed by flying bricks when a Union shell hit the house's chimney. At 6 p.m., the Union infantry charged. Egan and Pierce were supported by Col. William R. Brewster's brigade. Soldiers stabbed their bayonets into the earthworks and used them as makeshift ladders, allowing their comrades to climb up over their backs. Henagan's small force was overwhelmed and they fled across the bridge. They attempted to burn it behind them, but Union sharpshooters drove them off. Hancock's men did not attempt to cross the bridge and seize ground to the south because Alexander's artillery was laying down heavy fire against them. Instead, they entrenched on the northern bank of the river.[22]

At Jericho Mills, Warren found the river ford unprotected. He ordered Brig. Gen. Charles Griffin's division to wade across and establish a beachhead. By 4:30 p.m., the rest of the corps crossed on pontoon bridges. Hearing from a prisoner that Confederates were camped nearby at the Virginia Central Railroad, Warren arranged his men into battle lines: the division of Brig. Gen. Samuel W. Crawford lined up on the left, Griffin's on the right. Brig. Gen. Lysander Cutler's division then began moving onto Griffin's right. General Lee convinced his Third Corps commander, A.P. Hill, that Warren's movement was simply a feint, so Hill sent only a single division, commanded by Maj. Gen. Cadmus M. Wilcox, along with artillery commanded by Col. William J. Pegram, to deal with Warren's supposedly minor threat.[23]

Wilcox and Pegram delivered a firm blow. Crawford's division suffered heavy damage from the artillery and Griffin's division was hit hard by the North Carolinians of Brig. Gen. James H. Lane and the South Carolinians of Brig. Gen. Samuel McGowan. Cutler's wing, just arriving in line, was hit by the Georgians of Brig. Gen. Edward L. Thomas's brigade, more South Carolinians under Col. Brown, and the North Carolinians of Brig. Gen. Alfred M. Scales's brigade (temporarily commanded by Col. William L. Lowrance). Cutler's line was broken and his men fled to the rear, but their path of retreat led to the bluffs overlooking the North Anna. Warren's V Corps was rescued from a significant defeat by his artillery, commanded by Col. Charles S. Wainwright, which placed 12 guns on a ridge and subjected the Confederates to plunging fire. At the same time, the 83rd Pennsylvania led a portion of Brig. Gen. Joseph J. Bartlett's brigade down a ravine and struck the right flank of Thomas's Brigade. The Georgians fled, uncovering Scales's flank and leaving his men in an untenable position. Seeing that reinforcements from the division of Maj. Gen. Henry Heth would not arrive in time, Wilcox ordered his men to withdraw. He had been outnumbered about 15,000 to 6,000. His division suffered 730 casualties, including Col. Brown, who was captured; Union casualties were 377. The next morning, Robert E. Lee expressed his displeasure at Hill's performance: "General Hill, why did you let those people cross here? Why didn't you throw your whole force on them and drive them back as Jackson would have done?"[24]

May 23–24: Lee's defensive line

By the evening of May 23, Grant's line had formed at the North Anna. Warren's men dug in on their beachhead south of Jericho Mills. Wright arrived on the northern bank in support of Warren. Burnside stopped near Ox Ford on Wright's left, and Hancock remained on the northern bank to Burnside's left. Lee finally understood that a major battle was developing in this location and began to plan his defensive position. If he merely fortified the bluffs on the south bank of the river, Warren's artillery could enfilade him. Instead, Lee and his chief engineer, Maj. Gen. Martin L. Smith, devised a solution: a five-mile (8 km) line that formed an inverted "V" shape, sometimes called a "hog snout line", with its apex on the river at Ox Ford, the only defensible crossing in the area. On the western line of the V, reaching southwest to anchor on Little River, was the corps of A.P. Hill; on the east were Anderson and Ewell, extending through Hanover Junction and terminating behind a swamp. Lee's men worked nonstop overnight to complete the fortifications. Breckinridge and Pickett were in reserve on the Virginia Central Railroad.[25]

Lee's new position represented a significant potential threat to Grant. By moving south of the river, Lee hoped that Grant would assume that he was retreating, leaving only a token force to prevent a crossing at Ox Ford. Lee hoped that if Grant pursued, the pointed wedge of the inverted V would split his army and that Lee could leave a force of about 7,000 on the western arm of the V to keep Warren and Wright pinned down, then launch an attack against Hancock on the eastern arm of the V, concentrating his force to achieve local superiority, about 36,000 Confederate to 20,000 Union. Warren and Wright could come to Hancock's support only by crossing over the North Anna twice, a time-consuming exercise. As Lee had achieved at Spotsylvania Court House (and Meade at Gettysburg), interior lines could be used as a force multiplier; unlike the "Mule Shoe" at Spotsylvania, however, this position had the advantage of a strong anchor at the apex (the bluffs above Ox Ford), dissuading any attack from that direction. Lee confided to a local physician, "If I can get one more pull at [Grant], I will defeat him."[26]

May 24: Grant crosses the North Anna

On the morning of May 24, Grant sent additional troops south of the river. Wright's VI Corps crossed at Jericho Mills and by 11 a.m. both Warren and Wright had advanced to the Virginia Central Railroad. At 8 a.m., Hancock's II Corps finally crossed the Chesterfield Bridge, with the 20th Indiana and 2nd U.S. Sharpshooters dashing across to disperse a thin Confederate picket line. Downriver, the Confederates had burned the railway trestle, but soldiers from the 8th Ohio cut down a large tree and the men crossed on it single file. This was soon supplemented by a pontoon bridge and all of Maj. Gen. John Gibbon's division crossed. Grant had begun to fall into Lee's trap. Seeing the ease of crossing the river, he assumed the Confederates were retreating. He wired to Washington: "The enemy have fallen back from North Anna. We are in pursuit."[27]

The only visible opposition to the Union crossing was at Ox Ford, which Grant interpreted to be a rear guard action, simply an annoyance. Grant ordered Burnside's IX Corps to deal with it. To prepare for the river crossing, Burnside's division under Brig. Gen. Samuel W. Crawford marched upriver to Quarles Mill and seized the ford there. Burnside ordered Maj. Gen. Thomas L. Crittenden's division to cross over at the ford and follow the river's southern bank to Ox Ford and attack the Confederate position from the west. Crittenden's lead brigade was under Brig. Gen. James H. Ledlie, who was known for excessive drinking of alcohol in the field. Intoxicated and ambitious, Ledlie decided to attack the Confederate position with his brigade alone. Encountering the Confederate earthworks manned by Brig. Gen. William Mahone's division, Ledlie sent the 35th Massachusetts forward, but they were immediately repulsed. Ledlie sent an officer back to Crittenden to ask for three more regiments as reinforcements. The request surprised the division commander, who instructed the officer to tell Ledlie not to attack until the full division had crossed the river.[28]

_(14739681026).jpg.webp)

By the time the officer returned, Ledlie was completely drunk. When several Confederate artillery batteries on the earthworks were pointed out to Ledlie, he dismissed them and ordered a charge. His men stepped off as a rain began to fall, and in their rush toward the earthworks, the regiments became jumbled and confused. The Confederates waited to open fire until they were at close range, and the effect was to drive Ledlie's leading men into ditches for protection. As a violent thunderstorm erupted, the 56th and 57th Massachusetts regiments rallied, but Mahone's Mississippi troops stepped out of their works and shot them down. Col. Stephen M. Weld of the 56th Massachusetts was wounded and Lt. Col. Charles L. Chandler of the 57th was mortally wounded. Soon all of the Ledlie's men retreated to Quarles Mill. Despite his miserable performance, Ledlie received praise from his division commander that his brigade "behaved gallantly." He was promoted to division command after the battle and his drunkenness in the field continued to plague his men, culminating in his humiliating failure at the Battle of the Crater in July, after which he was relieved of command, never to receive another assignment.[29]

_(14762495302).jpg.webp)

Hancock's II Corps began pushing south from Chesterfield Bridge at about the same time that Ledlie was initially crossing the river. Hancock ordered Gibbon's division to advance down the railroad. After pushing aside Confederate skirmishers they ran into earthworks manned by the Alabama brigade of Brig. Gen. Evander M. Law and the North Carolina brigade of Col. William R. Cox. Gibbon's lead brigade under Col. Thomas A. Smyth attacked the earthworks, but the Confederates counterattacked, and soon most of Gibbon's division was engaged. The fierce fighting was briefly interrupted by the thunderstorm as men on both sides paused with concern that their gunpowder would be ruined. As the rain diminished, Maj. Gen. David B. Birney's division came to Gibbon's support, but even the combined force could not break the Confederate line.[30]

Although the Union army had done precisely what Lee had hoped it would do, the Confederate general was unable to capitalize on the situation. Lee suddenly suffered a debilitating attack of diarrhea and was forced to remain in his tent, bedridden. Unfortunately, he had no suitable subordinate commander to take over during his illness. Lt. Gen. A.P. Hill, who had become sick with an unidentified illness at the Wilderness had returned to duty, but was still sick and had performed poorly the previous day near Jericho Mills. Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell was exhausted from his ordeal at Spotsylvania. Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart had been mortally wounded at Yellow Tavern. His strongest subordinate, Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, had been wounded in the Wilderness and his replacement, Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson, was still inexperienced in corps-level command. Lee lamented in his tent, "We must strike them a blow—we must never let them pass again—we must strike them a blow." But Lee lacked the means to execute his plan.[31]

Most historians portray Lee's experience with the inverted V and his illness as a potential lost opportunity. However, some have shed doubt on this interpretation. Mark Grimsley has observed that the source of this view was Lee's aide-de-camp, Lt. Col. Charles S. Venable, who gave a speech about it in Richmond in 1873, which included the "we must strike them a blow" quotation. Grimsley notes that "no surviving contemporaneous correspondence alludes to such an operation, and the troop movements made on the night of May 23 and on May 24 were limited and defensive in nature." Furthermore, he describes the inverted V as a poor position from which to launch an offensive, lacking depth. Col. Vincent J. Esposito of the United States Military Academy wrote that the success of any Confederate assault was not assured because Hancock's men were well dug in.[32]

Ulysses S. Grant, Personal Memoirs[33]

At 6:30 p.m., Hancock warned Meade that Lee's position was as strong as that at Spotsylvania Court House. Grant finally realized the situation he faced with a divided army and ordered his men to stop advancing and to build earthworks of their own. His engineers began to construct pontoon bridges to improve the river crossings so that the separated wings of the army could support each other more expeditiously if needed.[34]

A significant command change occurred on the evening of May 24. Grant and Meade had had numerous quarrels during the campaign about strategy and tactics and tempers were reaching the boiling point. Grant mollified Meade somewhat by ordering that Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside and his IX Corps would henceforth report to Meade's Army of the Potomac, rather than to Grant directly. Although Burnside was a more senior major general than Meade, he accepted the new subordinate position without protest.[35]

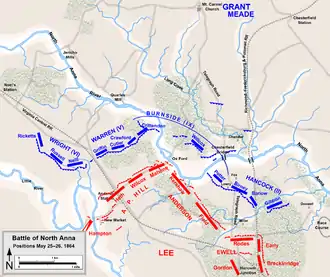

May 25–26: Stalemate

On the morning of May 25, Warren's V Corps probed A.P. Hill's line on the western leg of the V and judged it too strong to attack. Wright's VI Corps attempted to flank the Confederate line by crossing Little River, but found that Wade Hampton's cavalry was covering the fords. Hancock already knew the strength of the line facing him and did nothing further. For the rest of the day, light skirmishing occurred between the lines and Union soldiers occupied themselves by tearing up 5 miles of the Virginia Central Railroad, a key supply line from the Shenandoah Valley to Richmond. Grant's options were limited. The slaughter at Spotsylvania Court House ruled out the option of frontal attacks against the Confederate line and getting around either Confederate flank was infeasible.[36] However, the Union general remained optimistic. He was convinced that Lee had demonstrated the weakness of his army by not attacking when he had the upper hand. He wrote to the Army's chief of staff, Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck:

Lee's army is really whipped. The prisoners we now take show it, and the actions of his Army show it unmistakably. A battle with them outside of intrenchments cannot be had. Our men feel that they have gained the morale over the enemy, and attack him with confidence. I may be mistaken but I feel that our success over Lee's army is already assured.[37]

Aftermath

As he did after the Wilderness and Spotsylvania, Grant now planned another wide swing around Lee's flank, marching east of the Pamunkey River to screen his movements from the Confederates. He ordered (on May 22) that his supply depots at Belle Plain, Aquia Landing, and Fredericksburg be moved to a new base at Port Royal, Virginia, on the Rappahannock River. (Six days later the supply base was moved again, from Port Royal to White House on the Pamunkey.) He ordered Brig. Gen. James H. Wilson's cavalry division to cross the North Anna and move west, attempting to deceive Lee into thinking that the Union army intended to envelop the Confederate left flank. The cavalry destroyed more sections of the Virginia Central Railroad during this movement, but had no significant enemy contact. After dark on May 26, Wright and Warren disengaged and stealthily crossed over the North Anna. They marched east on May 27 toward the crossings over the Pamunkey River at Hanovertown, while Burnside and Hancock remained in place to guard the fords on the North Anna. The Union cavalry under Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan had returned by this time to screen the advance. The army's eventual goal was the important crossroads of Cold Harbor, 25 miles (40 km) southeast.[38]

Grant's optimism and his reluctance to assault strong defensive lines would be severely tested in the upcoming Battle of Cold Harbor. In the meantime, North Anna had proved to be a relatively minor affair when compared to other Civil War battles. Union casualties for the four days were 2,623.[4] Confederate casualties were not recorded, but based on the bloody fighting between A.P. Hill and Warren, it is probable they suffered between 1,500 and 2,500 casualties.[5]

Battlefield preservation

The North Anna Battlefield Park, opened in 1996 and maintained by Hanover County, Virginia, preserves a small section (75 acres) of the battlefield. Walking trails are available to inspect portions of the left side of the "inverted V" Confederate line up to Ox Ford.[39] In 2011, the Board of Supervisors approved a conditional use permit allowing expansion of the rock quarry (now operated by Martin Marietta Materials Inc. and American Aggregates Corporation). As part of the approval, the owner donated 90 acres to the County, including what is called the “killing fields” where the heaviest fighting took place.[40] The overall park now consists of 165 acres. In 2014, the Civil War Trust (a division of the American Battlefield Trust) acquired and preserved a 654-acre farm at the Jericho Mills part of the North Anna battlefield.[41] The Trust and its partners have acquired and preserved a total of 751 acres (3.04 km2) of the battlefield in three acquisitions since 2012.[42]

See also

Notes

- This Army Corps was under direct orders of Lieut. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant until May 24, 1864, when it was assigned to the Army of the Potomac. See: Official Records, Series I, Volume XXXVI, Part 1, page 113 (note at the bottom of the page).

- Kennedy, p. 289, cites 68,000 Union, 53,000 Confederate. Grimsley, pp. 138, cites 67,000 Union, 51–53,000 Confederate. Jaynes, p. 130, cites Union effectives of 56,124, indicating that Sheridan's cavalry was absent and not included. Cullen, p. 39, cites 100,000 Union, 50,000 Confederate.

- Return of Casualties in the Union forces, Battle of North Anna, Pamunkey, and Totopotomoy, May 22-June 1, 1864 (Total Army of the Potomac): Official Records, Series I, Volume XXXVI, Part 1, page 164.

- Kennedy, p. 289, cites 2,623. Salmon, p. 288, cites Union casualties of 2,600. Luebke cites 1,973 Union (223 killed, 1,460 wounded, 290 captured/missing) and 2,017 Confederate (304 killed, 1,513 wounded, 200 captured/missing).

- Young, p. 238, cites Confederate casualties including the actions at Guinea Station and Milford Station. Salmon, p. 288, cites 1,800 total Confederate casualties. Luebke cites 2,017 (304 killed, 1,513 wounded, 200 captured/missing).

- Hattaway & Jones, p. 525; Trudeau, pp. 29–30.

- Eicher, pp. 661–62; Kennedy, p. 282; Jaynes, pp. 25–26; Rhea, p. 369; Grimsley, pp. 94–110, 118–29, provides details on the failed campaigns (the Bermuda Hundred Campaign and Franz Sigel's campaign in the Shenandoah Valley) that were part of Grant's "peripheral strategy."

- Salmon, p. 253; Kennedy, pp. 280–82; Eicher, pp. 663–71; Jaynes, pp. 56–81.

- Jaynes, pp. 82–86, 114–24; Eicher, pp. 673–74; Salmon, pp. 270–71, 279–83; Kennedy, pp. 283, 286.

- Salmon, pp. 271–75; Kennedy, p. 285; Eicher, pp. 671–73, 675–76.

- Kennedy, p. 285; Salmon pp. 275–78; Eicher, pp. 676–78.

- Salmon, pp. 278–79; Kennedy, p. 286; Eicher, pp. 678–79; Jaynes, pp. 124–30.

- Rhea, pp. 378–84.

- Rhea, pp. 386–92.

- Welcher, p. 979; Esposito, text for map 135; Jaynes, p. 130.

- Rhea, pp. 157–59, 225–27; Jaynes, pp. 130–31.

- The 19th century spelling was Guiney's Station.

- Eicher, p. 683; Welcher, p. 977; Grimsley, pp. 134–35; Esposito, text for map 134; Trudeau, p. 218; Rhea, p. 212.

- Jaynes, p. 131; Welcher, p. 978.

- Rhea, pp. 251–52, 261–62; Jaynes, p. 131.

- Trudeau, p. 227; Rhea, pp. 282–89.

- Jaynes, p. 133; Kennedy, p. 287; Rhea, pp. 300–303.

- Cullen, p. 39; Welcher, p. 979; Kennedy, p. 289; Grimsley, pp. 139–40; Rhea, pp. 303–305; Jaynes, pp. 133–34.

- Rhea, pp. 305–16, 326; Salmon, p. 285; Cullen, p. 39; Welcher, pp. 979–80; Grimsley, p. 140; Trudeau, pp. 228–35.

- Welcher, 980; Grimsley, 141; Rhea, 320–24; Salmon, 285; Jaynes, 39. Jaynes is an example of the minority of historians who assert that Lee's defensive line was put immediately into place upon his arrival at the North Anna on May 22.

- Rhea, pp. 323, 325; Kennedy, p. 289; Jaynes, p. 135; Cullen, pp. 41–42; Trudeau, pp. 236, 241.

- Rhea, pp. 326, 331–32; Trudeau, p. 237.

- Trudeau, p. 239; Rhea, pp. 333–39; Salmon, p. 285; Jaynes, p. 136; Cullen, p. 40.

- Rhea, pp. 339–44; Salmon, p. 286; Jaynes, p. 136; Grimsley, p. 143; Trudeau, p. 240; Welcher, p. 855.

- Welcher, pp. 980–81; Rhea, pp. 346–50; Salmon, p. 286; Jaynes, p. 136.

- Rhea, pp. 344–46; Trudeau, p. 239; Grimsley, p. 145; Esposito, text for map 135. Freeman, vol. 3, pp. 358–59, depicts Lee's illness and the quotation about striking a blow as occurring on May 25.

- Grimsley, pp. 145–46; Esposito, text for map 135.

- Grant, ch. LIV, p. 12.

- Rhea, pp. 351–52.

- Welcher, p. 981; Trudeau, pp. 240–41; Rhea, pp. 352–53.

- Cullen, p. 42; Esposito, text for map 135; Trudeau, pp. 241–44; Rhea, pp. 355–60.

- Jaynes, p. 137; Grimsley, p. 148; Rhea, p. 368.

- Trudeau, p. 245; Welcher, pp. 981, 986; Grimsley, pp. 147–48; Salmon, p. 288.

- North Anna Battlefield Park Archived March 12, 2011, at the Wayback Machine; Historical markers at the North Anna battlefield

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-06-17. Retrieved 2014-06-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- American Battlefield Trust "Saved Land" webpage. Accessed May 29, 2018.

References

- Cullen, Joseph P. "Detour on the Road to Richmond." In Battle Chronicles of the Civil War: 1864, edited by James M. McPherson. Connecticut: Grey Castle Press, 1989. ISBN 1-55905-027-6. First published in 1989 by McMillan.

- Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Esposito, Vincent J. West Point Atlas of American Wars. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1959. OCLC 5890637. The collection of maps (without explanatory text) is available online at the West Point website.

- Freeman, Douglas S. R. E. Lee, A Biography. 4 vols. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1934–35. OCLC 166632575.

- Grant, Ulysses S. Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant. 2 vols. Charles L. Webster & Company, 1885–86. ISBN 0-914427-67-9.

- Grimsley, Mark. And Keep Moving On: The Virginia Campaign, May–June 1864. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002. ISBN 0-8032-2162-2.

- Hattaway, Herman, and Archer Jones. How the North Won: A Military History of the Civil War. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1983. ISBN 0-252-00918-5.

- Jaynes, Gregory, and the Editors of Time-Life Books. The Killing Ground: Wilderness to Cold Harbor. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1986. ISBN 0-8094-4768-1.

- Kennedy, Frances H., ed. The Civil War Battlefield Guide. 2nd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1998. ISBN 0-395-74012-6.

- Luebke, Peter. "Battle of North Anna." In Encyclopedia Virginia, edited by Brendan Wolfe. Virginia Foundation for the Humanities. Accessed September 15, 2010.

- Rhea, Gordon C. To the North Anna River: Grant and Lee, May 13–25, 1864. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-8071-2535-0.

- Salmon, John S. The Official Virginia Civil War Battlefield Guide. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2001. ISBN 0-8117-2868-4.

- Trudeau, Noah Andre. Bloody Roads South: The Wilderness to Cold Harbor, May–June 1864. Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1989. ISBN 978-0-316-85326-2.

- U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880–1901.

- Welcher, Frank J. The Union Army, 1861–1865 Organization and Operations. Vol. 1, The Eastern Theater. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989. ISBN 0-253-36453-1.

- Young, Alfred C., III. Lee's Army during the Overland Campaign: A Numerical Study. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0-8071-5172-3.

- National Park Service battle description

- CWSAC Report Update

Further reading

- Alexander, Edward P. Fighting for the Confederacy: The Personal Recollections of General Edward Porter Alexander. Edited by Gary W. Gallagher. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1989. ISBN 0-8078-4722-4.

- Carmichael, Peter S., ed. Audacity Personified: The Generalship of Robert E. Lee. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2004. ISBN 0-8071-2929-1.

- Catton, Bruce. Grant Takes Command. Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1968. ISBN 0-316-13210-1.

- Catton, Bruce. A Stillness at Appomattox. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1953. ISBN 0-385-04451-8.

- Foote, Shelby. The Civil War: A Narrative. Vol. 3, Red River to Appomattox. New York: Random House, 1974. ISBN 0-394-74913-8.

- Frassanito, William A. Grant and Lee: The Virginia Campaigns 1864–1865. New York: Scribner, 1983. ISBN 0-684-17873-7.

- Gallagher, Gary W., ed. The Wilderness Campaign. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997. ISBN 0-8078-2334-1.

- King, Curtis S., William Glenn Robertson, and Steven E. Clay. Staff Ride Handbook for the Overland Campaign, Virginia, 4 May to 15 June 1864: A Study in Operational-Level Command. Fort Leavenworth, KS: Combat Studies Institute Press, 2006. OCLC 62535944.

- Lyman, Theodore. With Grant and Meade: From the Wilderness to Appomattox. Edited by George R. Agassiz. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1994. ISBN 0-8032-7935-3.

- Miller, J. Michael. "Even to Hell Itself": The North Anna Campaign, May 21–26, 1864. Lynchburg, Virginia: H. E. Howard, 1989. ISBN 978-0-930919-71-9.

- Power, J. Tracy. Lee's Miserables: Life in the Army of Northern Virginia from the Wilderness to Appomattox. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998. ISBN 0-8078-2392-9.

- Rhea, Gordon C. The Battle of Cold Harbor. National Park Service Civil War series. Fort Washington, PA: U.S. National Park Service and Eastern National, 2001. ISBN 1-888213-70-1.

- Smith, Jean Edward. Grant. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-84927-5.

- Simpson, Brooks D. Ulysses S. Grant: Triumph over Adversity, 1822–1865. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2000. ISBN 0-395-65994-9.

- Wert, Jeffry D. The Sword of Lincoln: The Army of the Potomac. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005. ISBN 0-7432-2506-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of the North Anna River. |

- Battle of North Anna: Maps, histories, photos, and preservation news (Civil War Trust)

- Animated map of the Overland Campaign (Civil War Trust)

- Historical markers at the North Anna battlefield

- The North Anna and Movement from Spottsylvania, a series of 12 pen and ink maps in the Library of Congress, drawn by Robert E. L. Russell

- Animated history of the Overland Campaign