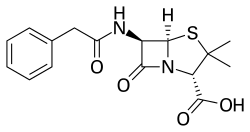

Benzylpenicillin

Benzylpenicillin, also known as penicillin G, is an antibiotic used to treat a number of bacterial infections.[3] This includes pneumonia, strep throat, syphilis, necrotizing enterocolitis, diphtheria, gas gangrene, leptospirosis, cellulitis, and tetanus.[3] It is not a first-line agent for pneumococcal meningitis.[3] Benzylpenicillin is given by injection into a vein or muscle.[2] Two long-acting forms benzathine benzylpenicillin and procaine benzylpenicillin are available for use by injection into a muscle.[3]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Pfizerpen, other |

| Other names | Penicillin G potassium,[2] penicillin G sodium |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| MedlinePlus | a685013 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | IV, IM |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | 60% |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 30 min |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| E number | E705 (antibiotics) |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.461 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C16H18N2O4S |

| Molar mass | 334.39 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Side effects include diarrhea, seizures, and allergic reactions including anaphylaxis.[3] When used to treat syphilis or Lyme disease a reaction known as Jarisch–Herxheimer may occur.[3] It is not recommended in those with a history of penicillin allergy.[3] Use during pregnancy is generally the penicillin and β-lactam class of medications.[3]

Benzylpenicillin was discovered in 1929 by Alexander Fleming and came into commercial use in 1942.[4] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[5]

Medical uses

Antimicrobial potency

As an antibiotic, benzylpenicillin is noted to possess effectiveness mainly against Gram-positive organisms. Some Gram-negative organisms such as Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Leptospira weilii are also reported to be susceptible to benzylpenicillin.[6]

Adverse effects

Adverse effects can include hypersensitivity reactions including urticaria, fever, joint pains, rashes, angioedema, anaphylaxis, serum sickness-like reaction. Rarely CNS toxicity including convulsions (especially with high doses or in severe renal impairment), interstitial nephritis, haemolytic anaemia, leucopenia, thrombocytopenia, and coagulation disorders. Also reported diarrhoea (including antibiotic-associated colitis).

Benzylpenicillin serum concentrations can be monitored either by traditional microbiological assay or by more modern chromatographic techniques. Such measurements can be useful to avoid central nervous system toxicity in any person receiving large doses of the drug on a chronic basis, but they are especially relevant to patients with kidney failure, who may accumulate the drug due to reduced urinary excretion rates.[7][8]

Manufacture

The production of benzylpenicillin involves fermentation, recovery and purification of the penicillin.[9]

The fermentation process of the production of benzylpencillin creates the product. The presence of the product in solution inhibits the reaction and reduces the product rate and yield. Thus, in order to obtain the most product and increase the rate of reaction, it is continuously extracted.[10] This is done by mixing the mold with either glucose, sucrose, lactose, starch, or dextrin, nitrate, ammonium salt, corn steep liquor, peptone, meat or yeast extract, and small amounts of inorganic salts.[11]

The recovery of the benzylpencillin is the most important part of the production process because it affects the later purification steps if done incorrectly.[9] There are several types of techniques used to recover benzyl penicillin: aqueous two-phase extraction, liquid membrane extraction, microfiltration, and solvent extraction.[9] Extraction is more commonly used in the recovery process.

In the purification step, the benzylpencillin is separated from the extraction solution. This is normally done by using a separation column.[12]

References

- David D. Dexter, James M. van der Veen (1978). "Conformations and a refinement of the structure of potassium penicillin G". J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1. 3 (3): 185–190. doi:10.1039/p19780000185. PMID 565366.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Penicillin G Injection - FDA prescribing information, side effects and uses". www.drugs.com. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR, eds. (2009). WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. pp. 98, 105. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 9789241547659.

- Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 490. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016.

- World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- "Penicillin G" (PDF). Toku-E. 10 October 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- Fossieck B Jr, Parker RH. Neurotoxicity during intravenous infusion of penicillin. A review. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 14: 504–512, 1974.

- Baselt R (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Foster City, CA: Biomedical Publications. pp. 1195–1196.

- Liu Q, Li Y, Li W, Liang X, Zhang C, Liu H (February 2016). "Efficient Recovery of Penicillin G by a Hydrophobic Ionic Liquid". ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering. 4 (2): 609–615. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.5b00975.

- Barros J (4 January 2016). "Use Extraction to Improve Penicillin G Recovery". American Chemical Society. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- "Separation and Purification of Pharmaceuticals and Antibiotics" (PDF).

- Saino Y, Kobayashi F, Inoue M, Mitsuhashi S (October 1982). "Purification and properties of inducible penicillin beta-lactamase isolated from Pseudomonas maltophilia". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 22 (4): 564–70. doi:10.1128/AAC.22.4.564. PMC 183794. PMID 6983856.

- Committee on Medical Research, O.S.R.D., Washington, and the Medical Research Council, London (1945). "Chemistry of Penicillin". Science. 102 (2660): 627–629. doi:10.1039/an9477200274.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Penicillin G". PubChem. National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

External links

- "Benzylpenicillin". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.