Al-Jalama, Tulkarm

Al-Jalama (Arabic: الجلمه) or Khirbat al-Jalama (Arabic: خربة الجلمه) was a Palestinian Arab village 8.5 kilometres (5.3 mi) north of Tulkarm. Situated close to the eastern banks of a valley of the same name (Wadi Jalama), it was inhabited during the Crusader and Mamluk periods, and again in Ottoman period by villagers from nearby Attil.

Al-Jalama

الجلمه | |

|---|---|

Village | |

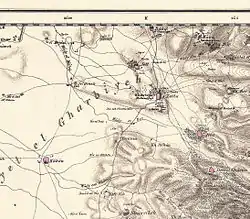

1870s map of the area around Al Jalama | |

| Etymology: "The heap"[1] | |

.jpg.webp) 1870s map 1870s map .jpg.webp) 1940s map 1940s map.jpg.webp) modern map modern map .jpg.webp) 1940s with modern overlay map 1940s with modern overlay mapA series of historical maps of the area around Al-Jalama, Tulkarm (click the buttons) | |

Al-Jalama Location within Mandatory Palestine | |

| Coordinates: 32°23′32″N 35°00′35″E | |

| Palestine grid | 151/199 |

| Geopolitical entity | Mandatory Palestine |

| Subdistrict | Tulkarm |

| Date of depopulation | 1 March 1950[2] |

| Population (1945) | |

| • Total | 70[3][4][5] |

| Current Localities | Lehavot Haviva |

Al-Jalama's population was expelled by the Israeli military on 1 March 1950 after it fell under Israeli rule as a result of the 1949 armistice agreement that ended the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. It was subsequently built over by the Israeli kibbutz of Lehavot Haviva.

History

In the Crusader period, Khirbet al-Jalama was known as Gelenna.[5]

In 1265, after the Mamluks had defeated the Crusaders, sultan Baybars made a grant of the village land to three of his amirs: Fakhr al-Din 'Uthman b. al-Malik al-Mughith, Shams al-Din Salar al-Baghdadi, and Sarim al-Din Siraghan.[6]

Ottoman era

Al-Jalama was incorporated into the Ottoman Empire in 1517 with all of Palestine, and in the 1596 tax records it was named Jalama dir Qaqun, part of nahiya (subdistrict) of Sara under the liwa' (district) of Lajjun. It had an all-Muslim population of 7 households, who paid a fixed tax rate of 25% on wheat, barley, summer crops, occasional revenues, beehives and/or goats; a total of 12,000 akçe.[7]

Pierre Jacotin named the village Tour de Zeitah on his map from Napoleon's invasion in 1799. The French fought a battle here, which is known as the "Battle of Zeita".[8]

In 1882, the PEF's Survey of Western Palestine (SWP) described the village as a small adobe hamlet, situated on the side of a knoll.[9]

British Mandate era

The modern village originated from farmland, belonging to the inhabitants of Attil. The farmers settled on the land nearby, and in the 1922 census there were 29 villagers, all Muslim.[5][10] In the 1931 census of Palestine it was counted under Attil (together with Al-Manshiyya and Zalafa),[11] while by the 1945 statistics al-Jalama had grown to a population of 70,[4] mainly belonging to two extended families, the Nadaf and the Daqqa.[12]

As the village was constructed on an old site, some archaeological remains were used for constructing houses. The houses were mainly constructed of stone or adobe. In the 1930s and 1940s, some houses were constructed of cement. The villagers, who were Muslim, grew watermelons, oranges and other crops. A well, 500 metres (1,600 ft) east of the village, provided water for domestic needs.[5]

1948, and aftermath

On the 3 April 1949, al-Jalama came under Israeli control with the signing of the Jordan–Israel Mixed Armistice Commission.[12][13] According to Article VI, section 6 in this Armistice Agreement, the villagers were "protected in, their full rights of residence, property and freedom." However, the Israeli annexation of the villages made them subject to laws that had the purpose of stripping them of their land so that the land could then be given to Jewish settlements, and to eliminate the possibility of return.[12][14]

During the period of clearing the borders of Palestinians, Israel emptied al-Jalama (now consisting of 225 people) on 1 March 1950.[2] They were expelled by the military to the neighbouring village of Jatt, a move that Meron Benvenisti called "unquestionably illegal".[15] The villagers petitioned the Supreme Court of Israel for permission to return, which was granted in June 1952. However, members from the kibbutz Lehavot Haviva had settled on their land. On 11 August 1953, they blew up the remaining houses in al-Jalama, thereby making sure that the Palestinian landowners could not return. The kibbutzniks claimed that the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) had ordered them to do this and had given them funds for that purpose. The IDF denied this.[2] Israel then passed several retroactive laws that legalised the expropriation of the al-Jalama land.[16]

References

- Palmer, 1881, p. 183

- Morris, 2004, pp. 533-4

- Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 21

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 75

- Khalidi, 1992, p. 554

- Ibn al-Furat, 1971, pp. 81, 210, 249 (map)

- Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 160

- Karmon, 1960, p. 170

- Conder and Kitchener, 1882, SWP II, p. 152

- Barron, 1923, Table IX, Sub-district of Tulkarem, p.27

- Mills, 1932, p. 53

- Benvenisti, 2002, p. 157

- UN Doc S/1302/Rev.1 of 3 April 1949 Archived 12 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Benvenisti, 2002, p. 158

- Benvenisti, 2002, p. 160

- Benvenisti, 2002, p. 161

Bibliography

- Barron, J. B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Benvenisti, M. (2002). Sacred Landscape: The Buried History of the Holy Land Since 1948. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-23422-2.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1882). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. 2. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945. Government of Palestine.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center. Archived from the original on 2018-12-08. Retrieved 2009-08-18.

- Hofnung, Menachem, (1991). Israel -Security vs the Rule of Law. Jerusalem: Nevo, (pp. 170–72, cited in Benvenisti)

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Ibn al-Furat (1971). J. Riley-Smith (ed.). Ayyubids, Mamluks and Crusaders: Selections from the "Tarikh Al-duwal Wal-muluk" of Ibn Al-Furat : the Text, the Translation. 2. Translation by Malcolm Cameron Lyons, Ursula Lyons. Cambridge: W. Heffer.

- Karmon, Y. (1960). "An Analysis of Jacotin's Map of Palestine" (PDF). Israel Exploration Journal. 10 (3, 4): 155–173, 244–253.

- Khalidi, W. (1992). All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, B. (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-00967-7.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

External links

- Welcome To al-Jalama

- al-Jalama (Tul-karem), Zochrot

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 11: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- Al- Jalama at Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center