Ethnic issues in China

Ethnic issues in China arise from Chinese history, nationalism, and other factors. They have driven historical movements such as the Red Turban Rebellion (which targeted the Mongol leadership of the Yuan Dynasty) and the Xinhai Revolution, which overthrew the Manchu Qing Dynasty. Ethnic tensions have led to incidents in the country such as the Xinjiang conflict, the ongoing Uyghur Genocide, the 2010 Tibetan language protest, the 2020 Inner Mongolia protests, Anti-Western sentiment in China and discrimination against Africans and people of African descent.

Background

China is a largely homogenous society; over 90% of its population has historically been Han Chinese.[1] Some of the country's ethnic groups are distinguishable by physical appearance and relatively-low intermarriage rates. Others have married Han Chinese and resemble them. A growing number of ethnic minorities are fluent at a native level in Mandarin Chinese. Children sometimes receive ethnic-minority status at birth if one of their parents belongs to an ethnic minority, even if their ancestry is predominantly Han Chinese. Pockets of immigrants and foreign residents exist in some cities.

A 100-day crackdown on illegal foreigners in Beijing began in May 2012, with Beijing residents wary of foreign nationals due to recent crimes.[2][3] China Central Television host Yang Rui said, controversially, that "foreign trash" should be cleaned out of the capital.[2]

.png.webp)

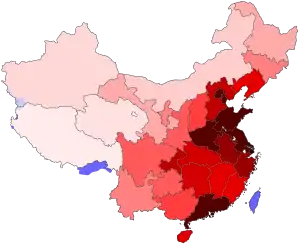

China is the most populated country in the world and its national population density (137/km2) is similar to those of Switzerland and the Czech Republic. The overall population density of China conceals major regional variations, the western and northern part have a few million people, while eastern half has about 1.3 billion. The vast majority of China's population lives near the east in major cities.

In the 11 provinces, special municipalities, and autonomous regions along the southeast coast, population density was 320.6 people per km2.

Broadly speaking, the population was concentrated east of the mountains and south of the northern steppe. The most densely populated areas included the Yangtze River Valley (of which the delta region was the most populous), Sichuan Basin, North China Plain, Pearl River Delta, and the industrial area around the city of Shenyang in the northeast.

Population is most sparse in the mountainous, desert, and grassland regions of the northwest and southwest. In Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, portions are completely uninhabited, and only a few sections have populations denser than ten people per km2. The Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, and Tibet autonomous regions and Qinghai and Gansu account for 55% of the country's land area but in 1985 contained only 5.7% of its population.

A 2010 population density map of the territories claimed by the PRC. Dark blue shaded regions reflect territory claimed but not controlled or governed by the PRC. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Language issues in China

There are several hundred languages in China. The predominant language is Standard Chinese, which is based on central Mandarin, but there are hundreds of related Chinese languages, collectively known as Hanyu (simplified Chinese: 汉语; traditional Chinese: 漢語; pinyin: Hànyǔ, 'Han language'), that are spoken by 92% of the population. The Chinese (or 'Sinitic') languages are typically divided into seven major language groups, and their study is a distinct academic discipline.[4] They differ as much from each other morphologically and phonetically as do English, German and Danish. There are in addition approximately 300 minority languages spoken by the remaining 8% of the population of China.[5] The ones with greatest state support are Mongolian, Tibetan, Uyghur and Zhuang.

Cantonese is a variety of Chinese spoken in the city of Guangzhou (also known as Canton) and its surrounding area in southeastern China. It is the traditional prestige variety and standard form of Yue Chinese, one of the major subgroups of Chinese. Mandarin Chinese as their first language, accounting for 71% of the country's population.[6]

Summary of varieties of Chinese

The number of speakers derived from statistics or estimates (2019) and were rounded:[7][8][9]

| Number | Branch | Native Speakers | Dialects |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mandarin | 850,000,000 | 51 |

| 2 | Wu | 95,000,000 | 37 |

| 3 | Yue | 80,000,000 | 52 |

| 4 | Jin | 70,000,000 | 6 |

| 5 | Min | 60,000,000 | 61 |

| 6 | Hakka | 55,000,000 | 10 |

| 7 | Xiang | 50,000,000 | 25 |

| 8 | Gan | 30,000,000 | 9 |

| 9 | Huizhou | 7,000,000 | 13 |

| 10 | Pinghua | 3,000,000 | 2 |

| Total | Chinese | 1,300,000,000 | 266 |

Mandarin

- 官话/官話

The number of speakers derived from statistics or estimates (2019) and were rounded:[9]

| Number | Branch | Native Speakers | Dialects |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Beijing | 35,000,000 | 7 |

| 2 | Ji–Lu | 110,000,000 | 4 |

| 3 | Jianghuai | 80,000,000 | 6 |

| 4 | Jiao–Liao | 35,000,000 | 4 |

| 5 | Lan–Yin | 10,000,000 | 3 |

| 6 | Northeastern | 100,000,000 | 4 |

| 7 | Southwestern | 280,000,000 | 11 |

| 8 | Zhongyuan | 200,000,000 | 11 |

| Total | Mandarin | 850,000,000 | 50 |

Summary of Han Chinese

The number of speakers derived from statistics or estimates (2019) and were rounded:[10][7][11]

History

Racial and Ethnic Conflicts in Imperial China

Racial slurs by the ruling Han Chinese in imperial China has been documented in historical texts such as Yan Shigu's commentary on the Book of Han, in which the Wusun people were called "barbarians who have green eyes and red hair" and compared to macaques.[12]

Massacres of Jie

Some ethnic conflicts were violent. During the 350 AD Wei–Jie war, the Chinese leader Ran Min massacred non-Chinese Wu Hu in retaliation for abuses against the Chinese population; the Jie people were particularly affected.[13] The Jie were identified by their big noses and beards while being slaughtered. In the period between 350 and 352, during the Wei–Jie war, General Ran Min ordered the complete extermination of the Jie, who were easily identified by high noses and full beards, leading to large numbers being killed.[14] According to some sources more than 200,000 of them were slain.[15]

Tang dynasty

Rebels slaughtered Arab and Persian merchants in the Yangzhou massacre (760). They were killed by Chinese rebels under Tian Shengong (T'ien Shen-kung). According to Arab historian Abu Zayd Hasan of Siraf, the rebel Huang Chao's army killed Arab, Jewish, Christian, and Parsi merchants in the Guangzhou massacre when he captured Guang Prefecture.[16]

The Tang dynasty Goguryeo general Gao Juren ordered a mass slaughter of Sogdian Caucasians identifying them through their big noses and lances were used to impale Caucasian children when he stormed Beijing (Fanyang) from An Lushan when he defeated An Lushan's rebels.[17][18]

Yuan dynasty

The Mongols divided groups into a four-class caste system during the Yuan dynasty. Merchants and non-Mongol overseers were usually immigrants or local ethnic groups: Turkestani and Persian Muslims and Christians. Foreigners from outside the Mongol Empire, such as the Polo family, were welcomed.

Bukhara and Samarqand were visited by Changchun. At the same time the Mongols imported Central Asian Muslims to serve as administrators in China, the Mongols also sent Han Chinese and Khitans from China to serve as administrators over the Muslim population in Bukhara and Samarqand in Central Asia, using foreigners to curtail the power of the local peoples of both lands. The surname of Li was held by one of Yelu Ahai's staff of Han Chinese. There were various Chinese craftsmen. Tangut, Khitan and Han Chinese took control over gardens and fields from the Muslims.[19] Han Chinese were moved to Central Asian areas like Besh Baliq, Almaliq, and Samarqand by the Mongols where they worked as artisans and farmers.[20] Alans were recruited into the Mongol forces with one unit called "Right Alan Guard" which was combined with "recently surrendered" soldiers, Mongols, and Chinese soldiers stationed in the area of the former Kingdom of Qocho and in Besh Balikh the Mongols established a Chinese military colony led by Chinese general Qi Kongzhi (Ch'i Kung-chih).[21]

After the Mongol conquest by Genghis Khan, foreigners were chosen as administrators and co-management with Chinese and Qara-Khitays (Khitans) of gardens and fields in Samarqand was put upon the Muslims as a requirement since Muslims were not allowed to manage without them.[22][23]

The Mongol appointed Governor of Samarqand was a Qara-Khitay (Khitan), held the title Taishi, familiar with Chinese culture his name was Ahai.[22]

Despite the Muslims' high position, the Yuan Mongols discriminated against them: restricting halal slaughter and other Islamic practices, such as circumcision (and kosher butchering for Jews). Genghis Khan called Muslims "slaves".[24][25] Muslim generals eventually joined the Han Chinese in rebelling against the Mongols. Ming dynasty founder Zhu Yuanzhang had Muslim generals (including Lan Yu) who rebelled against the Mongols and defeated them in battle. Semu-caste Muslims revolted against the Yuan dynasty in the Ispah rebellion, although the rebellion was crushed and the Muslims massacred by Yuan commander Chen Youding.

Anti-Muslim persecution by the Yuan dynasty and Ispah rebellion

The Yuan dynasty started passing anti-Muslim and anti-Semu laws and getting rid of Semu Muslim privileges towards the end of the Yuan dynasty, in 1340 forcing them to follow Confucian principles in marriage regulations, in 1329 all foreign holy men including Muslims had tax exemptions revoked, in 1328 the position of Muslim Qadi was abolished after its powers were limited in 1311. In the middle of the 14th century this caused Muslims to start rebelling against Mongol Yuan rule and joining rebel groups. In 1357-1367 the Yisibaxi Muslim Persian garrison started the Ispah rebellion against the Yuan dynasty in Quanzhou and southern Fujian. Persian merchants Amin ud-Din (Amiliding) and Saif ud-Din) Saifuding led the revolt. Persian official Yawuna assassinated both Amin ud-Din and Saif ud-Din in 1362 and took control of the Muslim rebel forces. The Muslim rebels tried to strike north and took over some parts of Xinghua but were defeated at Fuzhou two times and failed to take it. Yuan provincial loyalist forces from Fuzhou defeated the Muslim rebels in 1367 after A Muslim rebel officer named Jin Ji defected from Yawuna.[26]

The Muslim merchants in Quanzhou who engaged in maritime trade enriched their families which encompassed their political and trade activities as families. Historian John W. Chaffee saw the violent Chinese backlash that happened at the end of the Yuan dynasty against the wealth of the Muslim and Semu as something probably inevitable, although anti-Muslim and anti-Semu laws had already been passed by the Yuan dynasty. In 1340 all marriages had to follow Confucian rules, in 1329 all foreign holy men and clerics including Muslims no longer were exempt from tax, in 1328 the Qadi (Muslim headmen) were abolished after being limited in 1311. This resulted in anti-Mongol sentiment among Muslims so some anti-Mongol rebels in the mid 14th century were joined by Muslims. Quanzhou came under control of Amid ud-Din (Amiliding) and Saif ud-Din (Saifuding), two Persian military officials in 1357 as they revolted against the Mongols from 1357 to 1367 in southern Fujian and Quanzhou, leading the Persian garrison (Ispah) They fought for Fuzhou and Xinghua for 5 years. Both Saifuding and Amiliding were murdered by another Muslim called Nawuna in 1362 so he then took control of Quanzhou and the Ispah garrison for 5 more years until his defeat by the Yuan.[27]

Yuan Massacres of Muslims

The historian Chen Dasheng theorized that Sunni-Shia sectarian war contributed to the Ispah rebellion, claiming that the Pu family and their in-law Yawuna were Sunnis and there before the Yuan while Amiliding and Saifuding's Persian soldiers were Shia originally in central China and moved to Quanzhou and that Jin Ji was a Shia who defected to Chen Youding after Sunni Yawuna killed Amiliding and Saifuding. Three fates befell the Muslims and foreigners in Quanzhou, the ones in the Persian garrison were slaughtered, many Persians and Arab merchants fled abroad by ships, another small group that adopted Chinese culture were expelled into coastal Baiqi, Chendi, Lufu and Zhangpu and mountainous Yongchun and Dehua and one other part took refuge in Quanzhou's mosques. The genealogies of Muslim families which survived the transition are the main source of information for the rebellion times. The Rongshan Li family, one of the Muslim survivors of the violence in the Yuan-Ming transition period wrote about their ancestors Li Lu during the rebellion who was a businessman and shipped things, using his private stores to feed hungry people during the rebellion and using his connections to keep safe. The Ming takeover after the end of the Persian garrison meant that the diaspora of incoming Muslims ended. After the Persian garrison full and the rebellion was crushed, the common people started a slaughter of the Pu family and all Muslims: All of the Western peoples were annihilated, with a number of foreigners with large and big noses mistakenly killed while for three days the gates were closed and the executions were carried out. The corpses of the Pus were all stripped naked, their faces to the west. ... They were all judged according to the "five mutilating punishments" and then executed with their carcasses throwing into pig troughs. This was in revenge for their murder and rebellion in the Song.’’[28] (“是役也,凡西域人尽歼之,胡发高鼻有误杀者,闭门行诛三日。”“凡蒲尸皆裸体,面西方……悉令具五刑而诛之,弃其哉于猪槽中。”)[29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36]

80 merchant ships were commanded by Fo Lian, from Bahrain who was Pu Shougeng's son-in-law. The Qais born Supterintendent of Taxes for Persian and the Island, Jamal al-din Ibrahim Tibi had a son who was sent in 1297-1305 as an envoy to China. Wassaf, and Arab historian said that Jamal became wealthy due to trade with India and China. Patronage networks and monopolies controlled Yuan maritime trade unlike in the Song dynasty where foreigners and Chinese of the Song merchant elite reaped profits. Quanzhou's end as an international trading port was rapid as in 1357 rebellions broke out in central China so the Persian merchants Amin ud-din (Amiliding) and Saif ud-din (Saifuding) led soldiers to take over Quanzhou. A Pu family relative by marriage, Yawuna, another Muslim assassinated those two. The Muslim rebels of the Persian garrison in Quanzhou lasted a decade by exploiting maritime trade and plunder. Yawuna and his army were captured and defeated by provincial forces in 1366 and then the Ming took over Quanzhou 2 years later in 1368. Maritime trade was regulated and implemented extremely differently in the Ming dynasty. Guangzhou, Ningbo and Quanzhou all had maritime trade offices but they were limited to specific areas. The South Sea trade was no longer permitted in Quanzhou and only trade with Ryukyu was allowed in Quanzhou. The Muslim community in Quanzhou became a target of the people's anger. In the streets there was widescale slaughter of "big nosed" westerners and Muslims as recorded in a genealogical account of a Muslim family. The era of Quanzhou as an international trading port of Asia ended as did the role of Muslims as merchant diaspora in Quanzhou. Some Muslims fled by sea or land as they were persecuted by the locals and others tried to hide and lay low as depicted in the genealogies of Quanzhou Muslims despite the Ming emperors attempted to issue laws tolerating Islam in 1407 and 1368 and putting the notices in mosques.[37] Qais was the island of Kish and its king Jamal al-Din Ibrahim bin Muhammad al-Tibi briefly seized control of Hormuz while he traded with China and India and earned great wealth from it.[38]

One of Sayyid Ajall Shams al-Din Omar's descendants, the Jinjiang Ding fled to Chendai (Jinjiang) on the coast of Quanzhou to avoid the violence of the Ispah rebellion. The Li family survived through philanthropy activities however they said that in the rebellion "great families scattered from their homes, which were burned by the soldiers, and few genealogies survived." and used the words "a bubbling cauldron" to describe Quanzhou. In 1368 Quanzhou came under Ming control and the atmosphere calmed down for the Muslims. The Ming Yongle emperor issued decrees of protection from individuals and officials in mosques such as Quanzhou mosques and his father before him Ming Taizu had support from Muslim generals in his wars to reunify the country so he showed tolerance to them. The Ming passed some laws saying that Muslims not use Chinese surnames. Some genealogies of Muslims like the Li family show debate over teaching Confucian culture and classics like Odes and History or to practice Islam. Ming Taizu passed laws concerning maritime trade which were the major impact upon the life of Quanzhou Muslims. He restricted official maritime trade in Quanzhou to Ryukyu and Guangzhou was to monopolize south sea trade in the 1370s and 1403-1474 after initial getting rid of the Office of Maritime Trade altogether in 1370. Up to the late 16th century, private trade was banned.[39]

Persian Sunni Muslims Sayf al-din (Sai-fu-ding) and Awhad al-Din (A-mi-li-ding) started the Ispah rebellion in 1357 against the Yuan dynasty in Quanzhou and attempted to reach Fuzhou, capital of Fujian. Yuan general Chen Youding defeated the Muslim rebels and slaughtered Muslims of foreign descent in Quanzhou and areas next to Quanzhou. This led to many Muslim foreign fleeing to Java and other places in Southeast Asia to escape the massacres, spreading the Islamic religion. Gresik was ruled by a person from China's Guangdong province and it had a thousand Chinese families who moved there in the 14th century with the name Xin Cun (New Village) in Chinese. THis information was reported by Ma Huan who accompanied Zheng He to visit Java in the 15th century. Ma Huan also mentions Guangdong was the source of many Muslims from China who moved to Java. Cu Cu/Jinbun was said to be Chinese. And like most Muslims form China, Wali Sanga Sunan Giri was Hanafi according to Stamford Raffles.[40][41] Ibn Battuta had visited Quanzhou's large multi-ethnic Muslim community before the Ispah rebellion in 1357 when Muslim soldiers attempted to rebel against the Yuan dynasty. In 1366 the Mongols slaughtered the Sunni Muslims of Quanzhou and ended the rebellion. The Yuan dynasty's violent end saw repeated slaughters of Muslims until the Ming dynasty in 1368. The role of trade in Quanzhou ended as Sunni Muslims fled to Southeast Asia from Quanzhou. The surviving Muslims who fled Quanzhou moved to Manila bay, Brunei, Sumatra, Java and Champa to trade. Zheng He's historian Ma Huan noticed the presence of these Muslim traders in Southeast Asia who had fled form China in his voyages in Barus in Sumatra, Trengganu on the Malayan peninsula, Brunei and Java. The Nine Wali Sanga who converted Java to Islam had Chinese names and originated from Chinese speaking Quanzhou Muslims who fled there in the 14th century around 1368. The Suharto regime banned talk about this after Mangaradja Parlindungan, a Sumatran Muslim engineer wrote about it in 1964.[42]

Qing dynasty

Widespread violence against the Manchu people by Han Chinese rebels occurred during the Xinhai Revolution, most notably in Xi'an (where the Manchu quarter's population—20,000—was killed) and Wuhan (where 10,000 Manchus were killed).[43][44] Some scholars claim that the Manchus were seen as uncivilized and lacking culture, adopting Han Chinese and Tibetan culture instead.

Tensions erupted between Muslim sects, ethnic groups, the Tibetans and Han Chinese during the late 19th century near Qinghai.[45] According to volume eight of the Encyclopædia of Religion and Ethics, the Muslim Dungan and Panthay revolts were ignited by racial antagonism and class warfare.[46]

The Ush rebellion in 1765 by Uyghur Muslims against the Manchus occurred after Uyghur women were gang raped by the servants and son of Manchu official Su-cheng.[47][48][49] It was said that Ush Muslims had long wanted to sleep on [Sucheng and son's] hides and eat their flesh. because of the rape of Uyghur Muslim women for months by the Manchu official Sucheng and his son.[50] The Manchu Emperor ordered that the Uyghur rebel town be massacred, the Qing forces enslaved all the Uyghur children and women and slaughtered the Uyghur men.[51] Manchu soldiers and Manchu officials regularly having sex with or raping Uyghur women caused massive hatred and anger by Uyghur Muslims to Manchu rule. The invasion by Jahangir Khoja was preceded by another Manchu official, Binjing who raped a Muslim daughter of the Kokan aqsaqal from 1818 to 1820. The Qing sought to cover up the rape of Uyghur women by Manchus to prevent anger against their rule from spreading among the Uyghurs.[52]

The Manchu official Shuxing'a started an anti-Muslim massacre which led to the Panthay Rebellion. Shuxing'a developed a deep hatred of Muslims after an incident where he was stripped naked and nearly lynched by a mob of Muslims.[53][54]

The Hui Muslim community was divided in its support for the 1911 Xinhai Revolution. The Hui Muslims of Shaanxi supported the revolutionaries and the Hui Muslims of Gansu supported the Qing. The native Hui Muslims (Mohammedans) of Xi'an (Shaanxi province) joined the Han Chinese revolutionaries in slaughtering the entire 20,000 Manchu population of Xi'an.[55][56][57] The native Hui Muslims of Gansu province led by general Ma Anliang sided with the Qing and prepared to attack the anti-Qing revolutionaries of Xi'an city. Only some wealthy Manchus who were ransomed and Manchu females survived. Wealthy Han Chinese seized Manchu girls to become their slaves[58] and poor Han Chinese troops seized young Manchu women to be their wives.[59] Young pretty Manchu girls were also seized by Hui Muslims of Xi'an during the massacre and brought up as Muslims.[60]

Republic of China

Ethnic resentment resurfaced in at the end of the Qing Dynasty, in the early 20th century, as expemplified by Uyghur leader Sabit Damulla Abdulbaki's remarks about ROC Chinese and Tungans (Hui Muslims):

The Tungans, more than the Han, are the enemy of our people. Today our people are already free from the oppression of the Han, but still continue under Tungan subjugation. We must still fear the Han, but cannot fear the Tungans also. The reason we must be careful to guard against the Tungans, we must intensely oppose, cannot afford to be polite. Since the Tungans have compelled us, we must be this way. Yellow Han people have not the slightest thing to do with Eastern Turkestan. Black Tungans also do not have this connection. Eastern Turkestan belongs to the people of Eastern Turkestan. There is no need for foreigners to come be our fathers and mothers ... From now on we do not need to use foreigners language, or their names, their customs, habits, attitudes, written language, etc. We must also overthrow and drive foreigners from our boundaries forever. The colors yellow and black are foul. They have dirtied our land for too long. So now it is absolutely necessary to clean out this filth. Take down the yellow and black barbarians! Long live Eastern Turkestan!"[61][62]

An American telegram reported that Uyghur groups in parts of Xinjiang demanded the expulsion of White Russians and Han Chinese from Xinjiang during the Ili Rebellion. The Uyghurs reportedly said, "We freed ourselves from the yellow men, now we must destroy the white". According to the telegram, "Serious native attacks on people of other races frequent. White Russians in terror of uprising."[63]

A Hui soldier from the 36th Division called Swedish explorer Sven Hedin a "foreign devil",[64][65] and Tungans were reportedly "strongly anti-Japanese".[66] During the 1930s, a White Russian driver for Nazi agent Georg Vasel in Xinjiang was afraid to meet Hui general Ma Zhongying, saying: "You know how the Tungans hate the Russians." Vasel passed the Russian driver off as a German.[67]

A Chinese Muslim general encountered by writer Peter Fleming thought that his visitor was a foreign "barbarian" until he learned that Fleming's outlook was Chinese.[68] Fleming saw a Uyghur grovel at the general's feet, and other Uyghurs were treated contemptuously by his soldiers.[68][69] Racial slurs were allegedly used by the Chinese Muslim troops against Uyghurs.[70] Ma Qi's Muslim forces ravaged the Labrang Monastery over an eight-year period.[71][72]

Modern China

Anti-Japanese sentiment

Anti-Japanese sentiment primarily stems from Japanese war crimes which were committed during the Second Sino-Japanese War. History-textbook revisionism in Japan and the denial (or whitewashing) of events such as the Nanking Massacre by the Japanese far-right has continued to inflame anti-Japanese feeling in China. It has been alleged that anti-Japanese sentiment is also partially the result of political manipulation by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).[73] According to a BBC report, anti-Japanese demonstrations received tacit approval from Chinese authorities (although Chinese ambassador to Japan Wang Yi said that the Chinese government does not condone such protests).[74]

Conflict with Uyghurs

A Uyghur proverb says, "Protect religion, Kill the Han and destroy the Hui" (baohu zongjiao, sha Han mie Hui 保護宗教,殺漢滅回),[62][75] and anti-Hui poetry was written by Uyghurs:[76]

In Bayanday there is a brick factory,

it had been built by the Chinese.

If the Chinese are killed by soldiers,

the Tungans take over the plundering.

In the early 20th century, Uyghurs would reportedly not enter Hui mosques, and Hui and Han households were built together in a town; Uyghurs would live farther away.[76] Uyghurs have been known to view Hui Muslims from other provinces of China as hostile and threatening.[77][78][79] Mixed Han and Uyghur children are known as erzhuanzi (二转子); there are Uyghurs who call them piryotki,[78][80] and shun them.[81]

A book by Guo Rongxing on the unrest in Xinjiang states that the 1990 Baren Township riot protests were the result of 250 forced abortions imposed upon local Uyghur women by the Chinese government.[82]

The Chinese government and individual Han Chinese citizens have been accused of discrimination against and ethnic hatred towards the Uyghur minority.[83][84][85] This was a reported cause of the July 2009 Ürümqi riots, which occurred largely along racial lines. A People's Daily essay referred to the events as "so-called racial conflict",[86] and several Western media sources called them "race riots".[87][88][89] According to The Atlantic in 2009, there was an unofficial Chinese policy of denying passports to Uyghurs until they reached retirement age, especially if they intended to leave the country for the pilgrimage to Mecca.[83] A 2009 paper from the National University of Singapore reported that China's policy of affirmative action had actually worsened the rift between the Han and Uyghurs, but also noted that both ethnic groups could still be friendly with each other, citing a survey where 70% of Uyghur respondents had Han friends while 82% of Han had Uyghur friends.[90]

It was observed in 2013 that at least in the workplace, Uyghur-Han relations seemed relatively friendly.[91]

According to Central Asia-Caucasus Institute founder S. Fredrick Starr, tensions between Hui and Uyghurs arose because Qing and Republican Chinese authorities used Hui troops and officials to dominate the Uyghurs and suppress Uyghur revolts.[92] The massacre of Uyghurs by Ma Zhongying's Hui troops in the Battle of Kashgar caused unease as more Hui moved into the region from other parts of China.[93] Per Starr, the Uyghur population grew by 1.7 percent in Xinjiang between 1940 and 1982, and the Hui population increased by 4.4 percent, with the population-growth disparity serving to increase interethnic tensions.

Some Hui criticize Uyghur separatism. According to Dru C. Gladney, the Hui "don't tend to get too involved in international Islamic conflict. They don't want to be branded as radical Muslims."[94][95] Hui and Uyghurs live and worship separately.[96]

Han and Hui intermarry more than Uyghurs and Hui do, despite the latter's shared religion. Some Uyghurs believe that a marriage to a Hui is more likely to end in divorce.[97]

The Sibe tend to believe negative stereotypes of Uyghurs and identify with the Han.[98] According to David Eimer, one Han person had a negative view of Uyghurs but had a positive opinion of Tajiks in Tashkurgan.[99]

Yengisar (يېڭىسار, Йеңисар) is known for the manufacture of Uyghur handcrafted knives[100][101]—yingjisha (英吉沙刀 or 英吉沙小刀) in Chinese.[102][103][104][105][106] Although the wearing of knives by Uyghur men (indicating the wearer's masculinity) is a significant part of Uyghur culture,[107] it is seen as an aggressive gesture by others.[108] The Uyghur word for knife is pichaq (پىچاق, пичақ), and the plural is pichaqchiliq (پىچاقچىلىقى, пичақчилиқ).[109] Limitations were placed on knife vending due to terrorism and violent assaults where they were utilized.[110] Robberies and assaults committed by groups of Uyghurs, including children sold to (or kidnapped by) gangs, have increased tensions.[111][112][113] China has been working on multilateral anti-terrorism since the September 11 attacks and, according to the United Nations and the U.S. Department of State, some Uyghur separatist movements have been identified as terrorist groups.[114]

Ethnic Cleansing of Uyghurs

Since 2017, the Chinese government has pursued a policy which has led to more than one million Muslims (the majority of them Uyghurs) being held in secretive detention camps without any legal process.[115][116] Critics of the policy have described it as the sinicization of Xinjiang and called it an ethnocide or cultural genocide,[115][117][118][119][120][121] with many activists, NGOs, human rights experts, government officials, and the U.S. government calling it a genocide.[122][123][124][125][126][127][128][129] The Chinese government did not acknowledge the existence of these re-education camps until 2018 and called them "vocational education and training centers."[130][131] This name was changed to "vocational training centers" in 2019. The camps tripled in size from 2018 to 2019 despite the Chinese government claiming that most of the detainees had been released.[130]

There are widespread reports of forced abortion, contraception, and sterilization both inside and outside the re-education camps. NPR reports that a 37-year-old pregnant woman from the Xinjiang region said that she attempted to give up her Chinese citizenship to live in Kazakhstan but was told by the Chinese government that she needed to come back to China to complete the process. She alleges that officials seized the passports of her and her two children before coercing her into receiving an abortion to prevent her brother from being detained in an internment camp.[132] Zumrat Dwut, a Uyghur woman, claimed that she was forcibly sterilized by tubal ligation during her time in a camp before her husband was able to get her out through requests to Pakistani diplomats.[133][134] The Xinjiang regional government denies that she was forcibly sterilized.[133] The Associated Press reports that the there is a "widespread and systematic" practice of forcing Uyghur women to take birth control medication in the Xinjiang region,[135] and many women have stated that they have been forced to receive contraceptive implants.[136][137] The Heritage Foundation reported that officials forced Uyghur women to take unknown drugs and to drink some kind of white liquid that caused them to lose consciousness and sometimes causes them to cease menstruation altogether.[138]

Tahir Hamut, an Uyghur Muslim, worked in a labor camp during elementary school when he was a child, and he later worked in a re-education camp as an adult, performing such tasks as picking cotton, shoveling gravel, and making bricks. "Everyone is forced to do all types of hard labor or face punishment," he said. "Anyone unable to complete their duties will be beaten."[139]

Beginning in 2018, over one million Chinese government workers began forcibly living in the homes of Uyghur families to monitor and assess resistance to assimilation, and to watch for frowned-upon religious or cultural practices.[140][141] These government workers were trained to call themselves "relatives" and have been described in Chinese state media as being a key part of enhancing "ethnic unity". [140]

In March 2020, the Chinese government was found to be using the Uyghur minority for forced labor, inside sweat shops. According to a report published then by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), no fewer than around 80,000 Uyghurs were forcibly removed from the region of Xinjiang and used for forced labor in at least twenty-seven corporate factories.[142] According to the Business and Human Rights resource center, corporations such as Abercrombie & Fitch, Adidas, Amazon, Apple, BMW, Fila, Gap, H&M, Inditex, Marks & Spencer, Nike, North Face, Puma, PVH, Samsung, and UNIQLO each have each sourced from these factories prior to the publication of the ASPI report.[143]

Tibet

Many residents of the frontier districts of Sichuan and other Tibetan areas in China are of Han-Tibetan ethnicity, and are looked down on by Tibetans.[144] Tibetan Muslims, known as Kache in Tibetan, have lived peacefully with Tibetan Buddhists for over a thousand years because Buddhists are prohibited by their religion from killing animals but require meat to survive in their mountainous climate. However, Tibetans clash with the Hui (known as Kyangsha in Tibetan). Tibetans and Mongols refused to allow other ethnic groups (such as the Kazakhs) to participate in a ritual ceremony in Qinghai until Muslim general Ma Bufang reformed the practice.[145]

However, anti-Tibetan racism is also common among ethnic Han Chinese. Ever since its inception, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the sole legal ruling political party of the PRC (including Tibet), has been distributing historical documents which portray Tibetan culture as barbaric in order to justify Chinese control of the territory of Tibet, and is widely endorsed by Han Chinese nationalists. As such, many members of Chinese society have a negative view of Tibet which can be interpreted as racism. The traditional view is that Tibet was historically a feudal society which practiced serfdom/slavery and that this only changed due to Chinese influence in the region.

The CCP also promotes the view that some ancient Chinese historical figures strongly influenced many aspects of Tibet's fundamental culture as part of its campaign to legitimize Chinese control of Tibet. One such figure is Princess Wencheng, an ancient Chinese princess who purportedly married king Songsten Gampo of Tibet and introduced Buddhism as well as many other forms of "civilization" to Tibet.[146][147] Evidence for the legitimacy of the claims made about Princess Wencheng is limited.

According to Edward Friedman at the Council on Foreign Relations, many Han Chinese believe that ethnic minorities in China should be incorporated as part of the larger Chinese state.[148]

Tibetan-Muslim violence

Most Muslims in Tibet are Hui. Although hostility between Tibetans and Muslims stems from the Muslim warlord Ma Bufang's rule in Qinghai (the Ngolok rebellions (1917–49) and the Sino-Tibetan War), in 1949 the Communists ended violence between Tibetans and Muslims. However, recent Tibetan-Muslim violence occurred. Riots broke out between Muslims and Tibetans over a bone in soups and the price of balloons; Tibetans accused Muslims of being cannibals who cooked humans, attacking Muslim restaurants. Fires set by Tibetans burned the apartments and shops of Muslims, and Muslims stopped wearing their traditional headwear and began to pray in secret.[149] Chinese-speaking Hui also have problems with the Tibetan Hui (the Tibetan-speaking Kache Muslim minority).[150]

The main mosque in Lhasa was burned down by Tibetans, and Hui Muslims were assaulted by rioters in the 2008 Tibetan unrest.[151] Tibetan exiles and foreign scholars overlook sectarian violence between Tibetan Buddhists and Muslims.[152] Most Tibetans viewed the wars against Iraq and Afghanistan after the September 11 attacks positively, and anti-Muslim attitudes resulted in boycotts of Muslim-owned businesses.[153] Some Tibetan Buddhists believe that Muslims cremate their imams and use the ashes to convert Tibetans to Islam by making Tibetans inhale the ashes, although they frequently oppose proposed Muslim cemeteries.[154] Since the Chinese government supports the Hui Muslims, Tibetans attack the Hui to indicate anti-government sentiment and due to the background of hostility since Ma Bufang's rule; they resent perceived Hui economic domination.[155]

In 1936, after Sheng Shicai expelled 20,000 Kazakhs from Xinjiang to Qinghai, Hui troops led by Ma Bufang reduced the number of Kazakhs to 135.[156] Over 7,000 Kazakhs fled northern Xinjiang to the Tibetan Qinghai plateau region (via Gansu), causing unrest. Ma Bufang relegated the Kazakhs to pastureland in Qinghai, but the Hui, Tibetans and Kazakhs in the region continued to clash.[157]

In northern Tibet, Kazakhs clashed with Tibetan soldiers before being sent to Ladakh.[158] Tibetan troops robbed and killed Kazakhs at Chamdo, 400 miles (640 km) east of Lhasa, when the Kazakhs entered Tibet.[159][160] In 1934, 1935 and 1936–1938, an estimated 18,000 Kazakhs entered Gansu and Qinghai.[161] In 2017, the Dalai Lama compared the peacefulness of China's Muslims unfavorably to that of their Indian counterparts.[162]

Mongol discrimination

The CCP has been accused of sinicization by gradually replacing Mongolian languages with Mandarin Chinese. Critics call it cultural genocide for dismantling people's minority languages and eradicating their minority identities. The implementation of the Mandarin language policy began in Tongliao, because 1 million ethnic Mongols live there making it the most Mongolian-populated area. The 5 million Mongols are less than 20 percent of the population in Inner Mongolia.[163]

The 2020 Inner Mongolia protests were caused by a curriculum reform imposed on ethnic schools by the China's Inner Mongolia Department of Education. The two-part reform replace Mongolian as the medium of instruction by Standard Mandarin in three particular subjects and replace three regional textbooks, printed in Mongolian script, by the nationally-unified textbook series edited by the Ministry of Education, written in Standard Mandarin.[164][165][166] On a broader scale, the opposition to the curriculum change reflects the decline of regional language education in China.[167]

On 20 September 2020, up to 5,000 ethnic Mongolians were arrested in Inner Mongolia for protesting against enacted policies that outlaw their nomadic pastoralism lifestyle. The director of the Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center (SMHRIC), Enghebatu Togochog, called it “cultural genocide” by the CCP. Two-third of the 6 million ethnic Mongolians have a nomadic lifestyle that has been practiced for millennia.[168]

In October 2020, the Chinese regime asked Nantes History Museum in France not to use the words “Genghis Khan” and “Mongolia in the exhibition project dedicated to the history of Genghis Khan and the Mongol Empire. Nantes History Museum engaged the exhibition project in partnership with the Inner Mongolia Museum in Hohhot, China. Nantes History Museum stopped the exhibition project. The director of the Nantes museum, Bertrand Guillet, says: “Tendentious elements of rewriting aimed at completely eliminating Mongolian history and culture in favor of a new national narrative”.[169]

Discrimination against Africans and people of African descent

Scholars have noted that the People's Republic of China largely portrays racism as a Western phenomenon which has led to a lack of acknowledgement of racism in its own society.[170][171][172] The UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination reported in August 2018 that Chinese law does not define "racial discrimination" and lacks an anti-racial discrimination law in line with the Paris Principles.[173] In modern times, publicized incidents of discrimination against Africans have been the Nanjing anti-African protests in 1988 and a 1989 student-led protest in Beijing in response to an African dating a Chinese person.[174][175] Police action against Africans in Guangzhou has also been reported as discriminatory.[176][177][178][179] Reports of racism against Africans and black foreigners of African descent[180][181] in China grew during the COVID-19 pandemic in mainland China.[182][183][184] In response to criticism over COVID-19 related racism and discrimination against Africans in China, Chinese authorities set up a hotline for foreign nationals and laid out measures discouraging businesses and rental houses in Guangzhou from refusing people based on race or nationality.[185][186] Foreign Ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian claimed that the country has "zero tolerance" for discrimination.[179]

According to the BBC in 2020, many people in China have expressed solidarity for the Black Lives Matter movement.[187] The George Floyd protests have reportedly sparked conversations about race that would have not otherwise occurred in the country,[188] include treatment of China's own ethnic minorities.[189]

It has been reported since 2008 that many Africans have experienced racism in Hong Kong such as being subject to humiliating police searches on the street and getting blocked from bars and clubs.[190][191]

Discrimination against South Asians

There have been reports of widespread discrimination in Hong Kong against South Asian minorities regarding housing, employment, public services, and checks by the police.[192] A 2001 survey found that 82% of ethnic minority respondents said they had suffered discrimination from shops, markets, and restaurants in Hong Kong.[193] A 2020 survey found that more than 90% of ethnic minority respondents experienced some form of housing discrimination.[194] Foreign domestic workers, mostly South Asians, have been at risk of forced labor, subpar accommodation, and verbal, physical, or sexual abuse by employers.[195][196][197] A 2016 survey from Justice Centre Hong Kong suggested that 17% of migrant domestic workers were engaged in forced labor, while 94.6% showed signs of exploitation.[198]

Filipina women in Hong Kong are often reportedly stereotyped as promiscuous, disrespectful, and lacking self-control.[195] Reports of racist abuse from Hong Kong fans towards their Filipino counterparts at a 2013 football game came to light, after an increased negative image of the Philippines from the 2010 Manila hostage crisis.[199] In 2014, an insurance ad, as well as a school textbook, drew some controversy for alleged racial stereotyping of Filipina maids.[200]

Some Pakistanis in 2013 reported of banks barring them from opening accounts because they came from a 'terrorist country', as well as locals next to them covering their mouths thinking they smell, finding their beard ugly, or stereotyping them as claiming welfare benefits fraudulently.[201] A 2014 survey of Pakistani and Nepalese construction workers in Hong Kong found that discrimination and harassment from local colleagues led to perceived mental stress, physical ill health, and reduced productivity.[202][203] Some studies have attributed racial discrimination in the city partly to its post-colonial status, where white superiority remains present in the society.[204][205]

Ethnic slurs

- 鬼子 (guǐzi) – "Guizi", devils, refers to foreigners

- 日本鬼子 (rìběn guǐzi ) – literally "Japanese devil", used to refer to Japanese , can be translated as Jap . In 2010 Japanese internet users on 2channel created the fictional moe character Hinomoto Oniko (日本鬼子) which refers to the ethnic term, with Hinomoto Oniko being the Japanese kun'yomi reading of the Han characters "日本鬼子".[206]

- 二鬼子 (èr guǐzi ) – literally "second devil", used to refer to Korean soldiers who were a part of the Japanese army during the Sino-Japanese war in World War II.[207]

- 毛子 (máo zi) – literally "body hair" – a derogatory term for Caucasians. However, because most white people in contact with China were Russians before the 19th century, 毛子 became a derogatory term for Russians.[208][209]

According to historian Frank Dikötter,

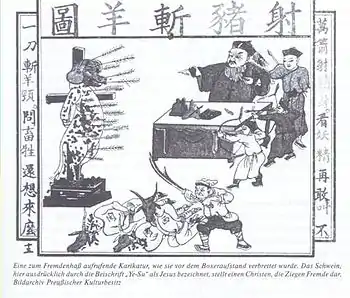

A common historical response to serious threats directed towards a symbolic universe is "nihilation", or the conceptual liquidation of everything inconsistent with official doctrine. Foreigners were labelled "barbarians" or "devils", to be conceptually eliminated. The official rhetoric reduced the Westerner to a devil, a ghost, an evil and unreal goblin hovering on the border of humanity. Many texts of the first half of the nineteenth century referred to the English as "foreign devils" (yangguizi), "devil slaves" (guinu), "barbarian devils" (fangui), "island barbarians" (daoyi), "blue-eyed barbarian slaves" (biyan yinu), or "red-haired barbarians" (hongmaofan).[210]

- Xiao Riben (小日本 Small Japanese)

- 鬼佬 – Gweilo, literally "ghostly man" (directed at white Westerners)

- 黑鬼 (hei guǐ)/(hak gwei) – "Black devil" (directed at Africans).[211][212]

- 妖精 – "Demons", used against Manchu people by the Taipings[213]

- 阿三 (A Sae) or 紅頭阿三 (Ghondeu Asae) - Originally a Shanghainese term used against Indians, it is also used in Mandarin.[214]

- chán-tóu (纏頭; turban heads) – used during the Republican period against Uyghurs[70][215]

- nǎozǐ jiǎndān (腦子簡單; simple-minded) – also used during the Republican period against Uyghurs[70]

- Erzhuanzi (二轉子) – children who are mixed Uyghur and Han[78][80] The term was said by European explorers in the 19th century to refer to a people descended from Chinese, Taghliks, and Mongols living in the area from Ku-ch'eng-tze to Barköl in Xinjiang.[216]

- Gaoli bangzi (高麗棒子 Korean Stick) - Used against Koreans, both North Koreans and South Koreans.

Etymology and ethnic biases

Chinese orthography provides opportunities to write ethnic insults logographically. Some Chinese characters used to transcribe the names of non-Chinese peoples were graphically-pejorative ethnic slurs, where the insult was not the Chinese word but the character used to write it. For example, the name of the Yao people was transcribed as 猺, a character which also means "jackal" and is written with the dog radical 犭. Being called a dog is a pejorative term in China. This name for the Yao, developed by 11th-century Song dynasty authors, has been replaced twice in 20th-century language reforms: with the invented character yao 傜 (with the human radical 亻) and with yao 瑤 (with the jade radical 玉), which can also mean "precious jade". Although the characters have the same pronunciation, they have different radicals (which convey different meanings).

See also

Notes

- "China". CIA. Retrieved 2007-04-24.

- Jemimah Steinfeld, 25 May 2012, Mood darkens in Beijing amid crackdown on 'illegal foreigners', CNN

- 15 May 2012, Beijing Pledges to ‘Clean Out’ Illegal Foreigners, China Real Time Report, Wall Street Journal

- Dwyer, Arienne (2005). The Xinjiang Conflict: Uyghur Identity, Language Policy, and Political Discourse (PDF). Political Studies 15. Washington: East-West Center. pp. 31–32. ISBN 978-1-932728-29-3.

Tertiary institutions with instruction in the languages and literatures of the regional minorities (e.g., Xinjiang University) have faculties entitled Hanyu xi ("Languages of China Department") and Hanyu wenxue xi ("Literatures of the Languages of China Department").

- Languages of China – from Lewis, M. Paul (ed.), 2009. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth edition. Dallas, Tex.: SIL International. "The number of individual languages listed for China is 299. "

- Mikael Parkvall, "Världens 100 största språk 2007" (The World's 100 Largest Languages in 2007), in Nationalencyklopedin. Asterisks mark the 2010 estimates for the top dozen languages.

- "Ethnologue: Languages of the World". Ethnologue.

- "Glottolog 4.2.1 -". glottolog.org.

- "Chinese". Ethnologue.

- "Basic facts of various ethnic groups". chinadaily.com.cn.

- "Top 100 Languages by Population - First Language Speakers". davidpbrown.co.uk.

- Book of Han, with commentary by Yan Shigu Original text: 烏孫於西域諸戎其形最異。今之胡人青眼、赤須,狀類彌猴者,本其種也。

- Mark Edward Lewis (2009). China between empires: the northern and southern dynasties. Harvard University Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-674-02605-6. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

ran min non chinese.

- Maenchen-Helfen, Otto J. (1973). The World of the Huns: Studies in Their History and Culture. University of California Press. p. 372. ISBN 0520015967. Retrieved January 16, 2015.

- The Buddhist Conquest of China, Erik Zürcher, page 111, https://books.google.com/books?id=388UAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA111&dq=CHIEH++people&hl=en&sa=X&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=CHIEH%20%20people&f=false

- Gabriel Ferrand, ed. (1922). Voyage du marchand arabe Sulaymân en Inde et en Chine, rédigé en 851, suivi de remarques par Abû Zayd Hasan (vers 916). p. 76.

- Hansen, Valerie (2003). "New Work on the Sogdians, the Most Important Traders on the Silk Road, A.D. 500-1000". T'oung Pao. 89 (1/3): 158. doi:10.1163/156853203322691347. JSTOR 4528925.

- Hansen, Valerie (2015). "CHAPTER 5 The Cosmopolitan Terminus of the Silk Road". The Silk Road: A New History (illustrated, reprint ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 157–158. ISBN 978-0190218423.

- Buell, Paul D. (1979). "Sino-Khitan administration in Mongol Bukhara". Journal of Asian History. 13 (2): 135–8. JSTOR 41930343.

- Michal Biran (15 September 2005). The Empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian History: Between China and the Islamic World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 96–. ISBN 978-0-521-84226-6.

- Morris Rossabi (1983). China Among Equals: The Middle Kingdom and Its Neighbors, 10th-14th Centuries. University of California Press. pp. 255–. ISBN 978-0-520-04562-0.

- E.J.W. Gibb memorial series. 1928. p. 451.

- "The Travels of Ch'ang Ch'un to the West, 1220-1223 recorded by his disciple Li Chi Ch'ang". Mediæval Researches from Eastern Asiatic Sources. E. Bretschneider. Barnes & Noble. 1888. pp. 37–108.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Michael Dillon (1999). China's Muslim Hui community: migration, settlement and sects. Richmond: Curzon Press. p. 24. ISBN 0-7007-1026-4. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Johan Elverskog (2010). Buddhism and Islam on the Silk Road. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 229, 230. ISBN 0-8122-4237-8. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Liu 刘, Yingsheng 迎胜 (2008). "Muslim Merchants in Mongol Yuan China". In Schottenhammer, Angela (ed.). The East Asian Mediterranean: Maritime Crossroads of Culture, Commerce and Human Migration. Volume 6 of East Asian economic and socio-cultural studies: East Asian maritime history (illustrated ed.). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 121. ISBN 978-3447058094. ISSN 1860-1812.

- Chaffee, John W. (2018). The Muslim Merchants of Premodern China: The History of a Maritime Asian Trade Diaspora, 750–1400. New Approaches to Asian History. Cambridge University Press. p. 157. ISBN 978-1108640091.

- Liu 刘, Yingsheng 迎胜 (2008). "Muslim Merchants in Mongol Yuan China". In Schottenhammer, Angela (ed.). The East Asian Mediterranean: Maritime Crossroads of Culture, Commerce and Human Migration. Volume 6 of East Asian economic and socio-cultural studies: East Asian maritime history (illustrated ed.). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 122. ISBN 978-3447058094. ISSN 1860-1812.

- "朱元璋为什么要将蒲寿庚家族中男的世世为奴,女的代代为娼?". Sohu. 2019-08-24.

- "蒲寿庚背叛宋朝投降元朝,为何蒲家后人却遭到元廷残酷打压!". 360kuai. Retrieved 2020-02-07.

- "南宋胡商蒲寿庚背叛南宋,他的子孙在明朝遭到怎样的对待?". wukongwenda.

- "朱元璋最恨的一个姓,男的世世为奴,女的世世代代为娼!". 优质资讯推荐. 2019-08-20.

- "朱元璋为什么要将蒲寿庚家族中男的世世为奴,女的代代为娼?". 优质资讯推荐. 2019-08-24.

- "此人屠殺三千宋朝皇族,死後被人挖墳鞭屍,朱元璋:家族永世為娼 原文網址:https://kknews.cc/history/xqx8g3q.html". 每日頭條. 每日頭條. 2018-05-22. External link in

|title=(help) - "蒲寿庚背叛宋朝投降元朝,为何蒲家后人却遭到元廷残酷打压". 新浪首页. 新浪首页. 12 June 2019.

- "此人屠杀三千宋朝皇族,死后被人挖坟鞭尸,朱元璋:家族永世为娼". 最新新闻 英雄联盟. 最新新闻 英雄联盟. 2019-11-26.

- Chaffee, John (2008). "4 At the Intersection of Empire and World Trade: The Chinese Port City of Quanzhou (Zaitun), Eleventh-Fifteenth Centuries". In Hall, Kenneth R. (ed.). Secondary Cities and Urban Networking in the Indian Ocean Realm, C. 1400-1800. G - Reference, Information and Interdisciplinary Subjects Series. Volume 1 of Comparative urban studies. Lexington Books. p. 115. ISBN 978-0739128350.

- Park, Hyunhee (2012). Mapping the Chinese and Islamic Worlds: Cross-Cultural Exchange in Pre-Modern Asia (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-1107018686.

- Liu 刘, Yingsheng 迎胜 (2008). "Muslim Merchants in Mongol Yuan China". In Schottenhammer, Angela (ed.). The East Asian Mediterranean: Maritime Crossroads of Culture, Commerce and Human Migration. Volume 6 of East Asian economic and socio-cultural studies: East Asian maritime history (illustrated ed.). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 123. ISBN 978-3447058094. ISSN 1860-1812.

- Wain, Alexander (2017). "Part VIII Southeast Asia and the Far East 21 CHINA AND THE RISE OF ISLAM ON JAVA". In Peacock, A. C. S. (ed.). Islamisation: Comparative Perspectives from History. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 434–435. ISBN 978-1474417143.

- Wain, Alexander (2017). "Part VIII Southeast Asia and the Far East 21 CHINA AND THE RISE OF ISLAM ON JAVA". In Peacock, A. C. S. (ed.). Islamisation: Comparative Perspectives from History. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 434–435. ISBN 978-1474417136.

- Reid, Anthony (2015). A History of Southeast Asia: Critical Crossroads. Blackwell History of the World. John Wiley & Sons. p. 102. ISBN 978-1118512951.

- Rhoads, Edward J. M. (2000). Manchus and Han: Ethnic Relations and Political Power in Late Qing and Early Republican China, 1861–1928. University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295980409.

- Rhoads, Edward J. M. (2017-05-01). Manchus and Han: Ethnic Relations and Political Power in Late Qing and Early Republican China, 1861-1928. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-99748-3.

- Nietupski (1999), p. 82

- James Hastings; John Alexander Selbie; Louis Herbert Gray (1916). Encyclopædia of religion and ethics, Volume 8. T. & T. Clark. p. 893. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- Millward, James A. (1998). Beyond the Pass: Economy, Ethnicity, and Empire in Qing Central Asia, 1759-1864. Stanford University Press. p. 124. ISBN 0804797927.

- Newby, L. J. (2005). The Empire And the Khanate: A Political History of Qing Relations With Khoqand C1760-1860 (illustrated ed.). BRILL. p. 39. ISBN 9004145508.

- Wang, Ke (2017). "Between the "Ummah" and "China":The Qing Dynasty's Rule over Xinjiang Uyghur Society" (PDF). Journal of Intercultural Studies. Kobe University. 48: 204.

- Millward, James A. (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. p. 108. ISBN 978-0231139243.

- Millward, James A. (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-0231139243.

- Millward, James A. (1998). Beyond the Pass: Economy, Ethnicity, and Empire in Qing Central Asia, 1759-1864. Stanford University Press. pp. 206–207. ISBN 0804797927.

- Atwill, David G. (2005). The Chinese Sultanate: Islam, Ethnicity, and the Panthay Rebellion in Southwest China, 1856-1873 (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Press. p. 89. ISBN 0804751595.

- Wellman, Jr., James K., ed. (2007). Belief and Bloodshed: Religion and Violence across Time and Tradition. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 121. ISBN 978-0742571341.

- Backhouse, Sir Edmund; Otway, John; Bland, Percy (1914). Annals & Memoirs of the Court of Peking: (from the 16th to the 20th Century) (reprint ed.). Houghton Mifflin. p. 209.

- The Atlantic, Volume 112. Atlantic Monthly Company. 1913. p. 779.

- The Atlantic Monthly, Volume 112. Atlantic Monthly Company. 1913. p. 779.

- Rhoads, Edward J. M. (2000). Manchus and Han: Ethnic Relations and Political Power in Late Qing and Early Republican China, 1861–1928 (illustrated, reprint ed.). University of Washington Press. p. 192. ISBN 0295980400.

- Rhoads, Edward J. M. (2000). Manchus and Han: Ethnic Relations and Political Power in Late Qing and Early Republican China, 1861–1928 (illustrated, reprint ed.). University of Washington Press. p. 193. ISBN 0295980400.

- Fitzgerald, Charles Patrick; Kotker, Norman (1969). Kotker, Norman (ed.). The Horizon history of China (illustrated ed.). American Heritage Pub. Co. p. 365.

- Zhang, Xinjiang Fengbao Qishinian [Xinjiang in Tumult for Seventy Years], 3393-4.

- The Islamic Republic of Eastern Turkestan and the Formation of Modern Uyghur Identity in Xinjiang, by JOY R. LEE

- "UNSUCCESSFUL ATTEMPTS TO RESOLVE POLITICAL PROBLEMS IN SINKIANG; EXTENT OF SOVIET AID AND ENCOURAGEMENT TO REBEL GROUPS IN SINKIANG; BORDER INCIDENT AT PEITASHAN" (PDF).

- Sven Hedin; Folke Bergman; Gerhard Bexell; Birger Bohlin; Gösta Montell (1945). History of the expedition in Asia, 1927-1935, Part 3. Göteborg, Elanders boktryckeri aktiebolag. p. 78. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Francis Hamilton Lyon, Sven Hedin (1936). The flight of "Big Horse": the trail of war in Central Asia. E. P. Dutton and co., inc. p. 92. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Forbes (1986), p. 130

- Georg Vasel; Gerald Griffin (1937). My Russian jailers in China. Hurst & Blackett. p. 143. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Fleming, Peter (1999). News from Tartary: A Journey from Peking to Kashmir. Northwestern University Press. ISBN 978-0-8101-6071-2.

- Christian Tyler (2004). Wild West China: the taming of Xinjiang. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. p. 265. ISBN 0-8135-3533-6. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Forbes, Andrew D. W.; Forbes, L. L. C. (1986-10-09). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: A Political History of Republican Sinkiang 1911-1949. CUP Archive. ISBN 978-0-521-25514-1.

- James Tyson; Ann Scott Tyson (1995). Chinese awakenings: life stories from the unofficial China. Westview Press. p. 123. ISBN 0-8133-2473-4. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Nietupski (1999), p. 90

- Shirk, Susan (2007-04-05). "China: Fragile Superpower: How China's Internal Politics Could Derail its Peaceful Rise". Archived from the original on 2007-07-07. Retrieved 2007-07-29.

- "China's anti-Japan rallies spread". BBC News. 2005-04-10.

- Robyn R. Iredale; Naran Bilik; Fei Guo (2003). China's minorities on the move: selected case studies. M.E. Sharpe. p. 170. ISBN 0-7656-1023-X. Retrieved 2010-07-30.

- Ildikó Bellér-Hann (2008). Community matters in Xinjiang, 1880-1949: towards a historical anthropology of the Uyghur. BRILL Publishers. p. 75. ISBN 978-90-04-16675-2. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Yangbin Chen (2008). Muslim Uyghur students in a Chinese boarding school: social recapitalization as a response to ethnic integration. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-7391-2112-2. Retrieved 2010-07-30.

- David Westerlund; Ingvar Svanberg (1999). Islam outside the Arab world. Routledge. p. 204. ISBN 0-312-22691-8. Retrieved 2010-07-30.

- Rudelson, Justin Jon; Rudelson, Justin Ben-Adam (1997). Oasis Identities: Uyghur Nationalism Along China's Silk Road (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. p. 63. ISBN 0231107862. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Ildikó Bellér-Hann (2007). Situating the Uyghurs between China and Central Asia. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-7546-7041-4. Retrieved 2010-07-30.

- Justin Ben-Adam Rudelson; Justin Jon Rudelson (1997). Oasis identities: Uyghur nationalism along China's Silk Road. Columbia University Press. p. 86. ISBN 0-231-10786-2. Retrieved 2010-07-30.

- Guo, Rongxing (15 July 2015). China's Spatial (Dis)integration: Political Economy of the Interethnic Unrest in Xinjiang. Chandos Publishing. ISBN 9780081004036. Archived from the original on 18 December 2020. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- "No Uighurs Need Apply". The Atlantic. 10 Jul 2009. Retrieved 12 July 2009.

- "Uighurs blame 'ethnic hatred'". Al Jazeera. July 7, 2009. Retrieved 12 July 2009.

- "Ethnic Minorities, Don't Make Yourself at Home". The Economist. 15 January 2015.

- Global Times (10 July 2009). "People's Daily criticizes double standards in Western media attitudes to 7.5 incident". China News Wrap. Archived from the original on 19 July 2009. Retrieved 13 July 2009. original article in Chinese

- "Race Riots Continue in China's Far West". Time magazine. 2009-07-07. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

- "Deadly race riots put spotlight on China". The San Francisco Chronicle. July 8, 2009. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

- "Three killed in race riots in western China". The Irish Times. July 6, 2009. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

- The Urumqi Riots and China's Ethnic Policy in Xinjiang (pages 20, 21) (PDF). National University of Singapore. 2009.

- Finley, Joanne N. Smith (2013-09-09). The Art of Symbolic Resistance: Uyghur Identities and Uyghur-Han Relations in Contemporary Xinjiang. BRILL Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-25678-1.

- Starr (2004), p. 311

- S. Frederick Starr (2004). Xinjiang: China's Muslim borderland. M.E. Sharpe. p. 113. ISBN 0-7656-1318-2. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Van Wie Davis, Elizabath. "Uyghur Muslim Ethnic Separatism in Xinjiang, China". Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Yardley, Jim (Feb 16, 2006). "China's Muslims remain quiet". The Tuscaloosa News. p. 9A.

- Safran, William (1998). Nationalism and ethnoregional identities in China. Psychology Press. p. 35. ISBN 0-7146-4921-X. Retrieved 2011-01-11.

- Finley, Joanne N. Smith (2013). The Art of Symbolic Resistance: Uyghur Identities and Uyghur-Han Relations in Contemporary Xinjiang (illustrated ed.). BRILL. p. 337. ISBN 978-9004256781. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Rachel Harris (23 December 2004). Singing the Village: Music, Memory and Ritual Among the Sibe of Xinjiang. OUP/British Academy. pp. 45–. ISBN 978-0-19-726297-9.

- David Eimer (14 August 2014). The Emperor Far Away: Travels at the Edge of China. A&C Black. pp. 70–. ISBN 978-1-4088-1322-5.

- China. Eye Witness Travel Guides. p. 514.

- "Two Weeks Wild scenery of Xinjiang - Silk Road Tours China". Archived from the original on 2015-12-08.

- "新疆的英吉沙小刀(组图)". china.com.cn. Archived from the original on December 19, 2013.

- "The Uyghur Nationality". Oriental Nationalities. Archived from the original on 2014-05-20.

- "英吉沙小刀".

- "Loving Nanjiang 15 days - Sichuan, China Youth Travel Service".

- wangyuliang. "Specialties and Sports of the Uyghur Ethnic Minority".

- "英吉沙小刀". sinobuy.cn. Archived from the original on 2015-11-09.

- "Kunming attack further frays ties between Han and Uighurs". TODAYonline.

- "شىنجاڭ دېھقانلار تورى". Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2016-08-13.

- Makinen, Julie (17 September 2014). "For China's Uighurs, knifings taint an ancient craft". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- Jacobs, Andrew (3 March 2014). "Train Station Rampage Further Strains Ethnic Relations in China". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- Demick, Barbara (21 August 2011). "China's Uighur petitioners face abuse in Beijing". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- "China tightens adoption rules to fight child trafficking". The Guardian. Associated Press. 16 August 2011. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- Wayne, Martin I. (2008). China's war on terrorism counter- insurgency, politics, and internal security (1. publ. ed.). Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-0203936139.

- "'Cultural genocide': China separating thousands of Muslim children from parents for 'thought education'". The Independent. 5 July 2019. Archived from the original on 22 April 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- "UN: Unprecedented Joint Call for China to End Xinjiang Abuses". Human Rights Watch. 10 July 2019. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- "'Cultural genocide' for repressed minority of Uighurs". The Times. 17 December 2019. Archived from the original on 25 April 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- "China's Oppression of the Uighurs 'The Equivalent of Cultural Genocide'". Der Spiegel. 28 November 2019. Archived from the original on 21 January 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- "Fear and oppression in Xinjiang: China's war on Uighur culture". Financial Times. 12 September 2019. Archived from the original on 14 April 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- "The Uyghur Minority in China: A Case Study of Cultural Genocide, Minority Rights and the Insufficiency of the International Legal Framework in Preventing State-Imposed Extinction". November 2019. Archived from the original on 2020-02-15. Retrieved 2020-04-27.

- "China's crime against Uyghurs is a form of genocide". Summer 2019. Archived from the original on 2020-02-01. Retrieved 2020-04-27.

- Carbert, Michelle (20 July 2020). "Activists urge Canada to recognize Uyghur abuses as genocide, impose sanctions on Chinese officials". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- Steger, Isabella (20 August 2020). "On Xinjiang, even those wary of Holocaust comparisons are reaching for the word "genocide"". Quartz. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- "Menendez, Cornyn Introduce Bipartisan Resolution to Designate Uyghur Human Rights Abuses by China as Genocide". foreign.senate.gov. United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations. October 27, 2020. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- "Blackburn Responds to Offensive Comments by Chinese State Media". U.S. Senator Marsha Blackburn of Tennessee. December 3, 2020. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- Alecci, Scilla (October 14, 2020). "British lawmakers call for sanctions over Uighur human rights abuses". International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- "Committee News Release - October 21, 2020 - SDIR (43-2)". House of Commons of Canada. October 21, 2020. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- Pompeo, Mike (2021-01-19). "Genocide in Xinjiang". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2021-01-19.

- Gordon, Michael R. (19 January 2021). "U.S. Says China Is Committing 'Genocide' Against Uighur Muslims". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- Maizland, Lindsay. "China's Repression of Uighurs in Xinjiang". Council on Foreign Relations.

- Cheng, June (30 October 2018). "Razor-wire evidence". World. Archived from the original on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 2020-10-21.

- "'They Ordered Me To Get An Abortion': A Chinese Woman's Ordeal In Xinjiang". NPR. Archived from the original on 2019-12-03. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- CNN, Ivan Watson, Rebecca Wright and Ben Westcott (21 September 2020). "Xinjiang government confirms huge birth rate drop but denies forced sterilization of women". CNN. Archived from the original on 27 September 2020. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- "First she survived a Uighur internment camp. Then she made it out of China". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2019-12-05. Retrieved 2019-12-04.

- "China cuts Uighur births with IUDs, abortion, sterilization". Associated Press. June 28, 2020. Archived from the original on 16 December 2020. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- "China 'using birth control' to suppress Uighurs". BBC News. 2020-06-29. Archived from the original on 2020-06-29. Retrieved 2020-07-07.

- "China accused of genocide over forced abortions of Uighur Muslim women as escapees reveal widespread sexual torture". The Independent. 2019-10-06. Archived from the original on 2019-12-08. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- Enos, Olivia; Kim, Yujin (29 August 2019). "China's Forced Sterilization of Uighur Women Is Cultural Genocide". The Heritage Foundation. Archived from the original on 2 December 2019. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- "China profiting off of forced labor in Xinjiang: report". aa.com.tr. Archived from the original on 2019-12-09. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- Byler, Darren (9 November 2018). "Why Chinese civil servants are happy to occupy Uyghur homes in Xinjiang". CNN.

- Westcott, Ben; Xiong, Yong. "Xinjiang's Uyghurs didn't choose to be Muslim, new Chinese report says". CNN. Archived from the original on 2019-12-19. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- Xu, Vicky Xiuzhong; Cave, Danielle; Leiboid, James; Munro, Kelsey; Ruser, Nathan (February 2020). "Uyghurs for Sale". Australian Strategic Policy Institute. Retrieved 2021-01-20.

- https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/latest-news/china-83-major-brands-implicated-in-report-on-forced-labour-of-ethnic-minorities-from-xinjiang-assigned-to-factories-across-provinces-includes-company-responses/

- Friedrich Ratzel (1898). The history of mankind, Volume 3. Macmillan and co., ltd. p. 355. Retrieved 2010-07-30.

- Uradyn Erden Bulag (2002). Dilemmas The Mongols at China's edge: history and the politics of national unity. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 54. ISBN 0-7425-1144-8. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- "Tibetan Ethnic Group". ChinaCulture.org (This is a state-owned website which reflects the official views of the Chinese government.). 2011.

In the 7th century AD, the Tibetan king, Songtsan Gampo, unified the whole region and established the Tubo Dynasty (629-846). The marriage of this Tibetan king to Princess Wencheng from Chang'an (modern-day Xian, the then capital of the Tang Dynasty (618-907)) and Princess Chizun from Nepal helped to introduce Buddhism and develop Tibetan culture.

- "Tibet's history during Tang dynasty". Embassy of the People's Republic of China in India (This is a website which is directly administered by the Chinese government.). 2009.

In 641, Princess Wencheng of the Tang Dynasty married Srongtsen Gampo. She brought to Tibet advanced cultures such as astronomical reckoning, agricultural techniques, medicines, paper making and sculpturing, as well as agricultural technicians, painters and architects, thus promoting the economic and cultural development in Tibet.

- Edward Friedman (2008). "Friedman: Chinese Believe Tibetans, Other Ethnic Groups Should be Incorporated into One China". Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 2020-11-19.

- Demick, Barbara (23 June 2008). "Tibetan-Muslim tensions roil China". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 22, 2010. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Mayaram, Shail (2009). The other global city. Taylor Francis US. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-415-99194-0. Retrieved 2010-07-30.

- "Police shut Muslim quarter in Lhasa". CNN. LHASA, Tibet. 28 March 2008. Archived from the original on April 4, 2008.

- Fischer (2005), pp. 1–2

- Fischer (2005), p. 17

- Fischer (2005), p. 19

- A.A. (Nov 11, 2012). "The living picture of frustration". The Economist. Retrieved 2014-01-15.

- American Academy of Political and Social Science (1951). The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Volume 277. American Academy of Political and Social Science. p. 152. Retrieved 2012-09-29.

A group of Kazakhs, originally numbering over 20000 people when expelled from Sinkiang by Sheng Shih-ts'ai in 1936, was reduced, after repeated massacres by their Chinese coreligionists under Ma Pu-fang, to a scattered 135 people.

- Lin (2011), p. 112,

- Lin (2011), p. 231,

- Blackwood's Magazine. William Blackwood. 1948. p. 407.

- Devlet, Nâdir (2005). Studies in the politics, history and culture of Turkic peoples. Istanbul: Yeditepe University. p. 192. OCLC 680361748.

- Linda Benson (1988). The Kazaks of China: Essays on an Ethnic Minority. Ubsaliensis S. Academiae. p. 195. ISBN 978-91-554-2255-4.

- "Indian Muslims are peace loving: Dalai lama". The Times Of India. Hyderabad. Feb 12, 2017.

- Jianli Yang and Lianchao Han (7 July 2020). "China is replacing languages of ethnic minorities with Mandarin". The Hill. Archived from the original on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- Qin, Amy (2020-08-31). "Curbs on Mongolian Language Teaching Prompt Large Protests in China". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-09-02.

- "全区民族语言授课学校小学一年级和初中一年级使用国家统编《语文》教材实施方案政策解读" [Policy Interpretation: the Implementation of Nationally-unified Textbook Series on "Language and Literature" in Ethnic schools across Inner Mongolia starting from First and Seventh Grade] (in Chinese). Government of Ud District, Wuhai City, Inner Mongolia. Inner Mongolia Daily (内蒙古日报). 2020-08-31. Archived from the original on 2020-09-04.

- ""五個不變"如何落地 自治區教育廳權威回應" [How "Five things unchanged" is implemented? Inner Mongolia's Department of Education Authoritative Response]. The Paper (澎湃新聞). Retrieved 2020-09-05.

- "Students in Inner Mongolia protest Chinese language policy". Taipei: The Japan Times. Associated Press. 2020-09-03.

- HKT (20 September 2020). "Thousands arrested in Inner Mongolia for defending nomadic herding lifestyle". Apple Daily. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- Beauvallet, Ève. "Nantes History Museum resists Chinese regime censorship". Archyde. Archived from the original on 13 October 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- Peck, Andrew (2012). Ai, Ruixi (ed.). Nationalism and Anti-Africanism in China. Flying Dragon. pp. 29–38. ISBN 978-1-105-76890-3. OCLC 935463519.

- Sautman, Barry (1994). "Anti-Black Racism in Post-Mao China". The China Quarterly. 138 (138): 413–437. doi:10.1017/S0305741000035827. ISSN 0305-7410. JSTOR 654951.

- "China portrays racism as a Western problem". The Economist. 2018-02-22. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2019-06-08.

- "Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination reviews the report of China". ohchr.org. August 13, 2018. Retrieved 2019-06-09.

- Sullivan, Michael J. (June 1994). "The 1988–89 Nanjing Anti-African Protests: Racial Nationalism or National Racism?". The China Quarterly. 138 (138): 438–457. doi:10.1017/S0305741000035839. ISSN 0305-7410. JSTOR 654952.

- Kristof, Nicholas D. (1989-01-05). "Africans in Beijing Boycott Classes". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-09-29.

- Huang, Guangzhi (2019-03-01). "Policing Blacks in Guangzhou: How Public Security Constructs Africans as Sanfei". Modern China. 45 (2): 171–200. doi:10.1177/0097700418787076. ISSN 0097-7004. S2CID 149683802.

- Marsh, Jenni (September 26, 2016). "The African migrants giving up on the Chinese dream". CNN. Retrieved 2019-07-14.

- Chiu, Joanna (March 30, 2017). "China has an irrational fear of a "black invasion" bringing drugs, crime, and interracial marriage". Quartz. Retrieved April 10, 2020.

- Marsh, Jenni. "China says it has a 'zero-tolerance policy' for racism, but discrimination towards Africans goes back decades". cnn.com. CNN. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- Chambers, Alice; Davies, Guy. "How foreigners, especially black people, became unwelcome in parts of China amid COVID crisis". abcnews.go.com. ABC News. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- Kanthor, Rebecca. "Racism against African Americans in China escalates amid coronavirus". pri.org. Public Radio International. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- Shikanda, Hellen; Okinda, Brian (April 10, 2020). "Outcry as Kenyans in China hit by wave of racial attacks". Daily Nation. Retrieved April 10, 2020.

- "'They deny us everything': Africans under attack in China". BBC. Retrieved 2020-04-10.

- "Coronavirus: Africans in China subjected to forced evictions, arbitrary quarantines and mass testing". Hong Kong Free Press. Agence France-Presse. April 12, 2020. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- Asiedu, Kwasi Gyamfi. "After its racism to Africans goes global, a Chinese province is taking anti-discrimination steps". Quartz Africa. Retrieved 2020-11-19.

- "China province launches anti-racism push after outrage". The Hindu, Agence France Presse. 2020-05-04. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2020-11-19.

- "Investigation into US professor sparks debate over Chinese word". BBC News. 2020-09-10. Retrieved 2020-11-19.

- "'How George Floyd's death changed my Chinese students'". BBC News. 2020-06-28. Retrieved 2020-11-19.

- "Has the killing of George Floyd sparked a 'racial awakening' in China?". Deutsche Welle. July 2020. Retrieved 2020-11-19.

- Tharoor, Ishaan (2008-07-14). "HK's Half-Baked Anti-Racism Law". Time Magazine. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 2020-11-19.

- "What it's like to be black and African in Hong Kong". South China Morning Post. 2020-08-02. Retrieved 2020-11-19.

- Jessie Yeung. "Spat at, segregated, policed: Hong Kong's dark-skinned minorities say they've never felt accepted". CNN. Retrieved 2020-11-19.

- "Topic: Situation of racial discrimination in Hong Kong - A background paper for the Social Science Forum held on 1 November 2001". City University of Hong Kong. 2001.

- "Discrimination rampant for members of Hong Kong minority groups seeking housing, survey finds". South China Morning Post. 2020-10-05. Retrieved 2020-11-19.

- Rutherford, Kylan (2019-01-19). "Forced Labor in Hong Kong". Brigham Young University - Marriott Student Review. 2 (3).

- Hampshire, Angharad (2016-03-14). "Forced labour common among Hong Kong's domestic helpers, study finds". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2020-11-19.

- "Foreign Domestic Worker Abuse Is Rampant in Hong Kong". 16 Days Campaign. 2019-01-16. Retrieved 2020-11-19.

- Ho, Kelly (2020-04-06). "Hungry and indebted: Kenyan domestic worker falls victim to forced labour in Hong Kong". Hong Kong Free Press. Retrieved 2020-11-19.

- Kelvin Chan (June 2013). "HK investigates racism at Philippines friendly". Associated Press. Retrieved 2020-11-19.

- "'Racist' maid ad draws anger in Hong Kong". Philippine Daily Inquirer, Agence France-Presse. 2014-06-18. Retrieved 2020-11-19.