Climate of Florida

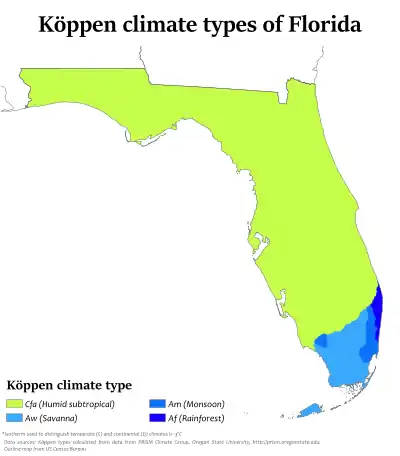

The climate of the north and central parts of the US state of Florida is humid subtropical. Most of South Florida has a tropical climate.[1] There is a defined rainy season from May through October, when air mass thundershowers that build in the heat of the day drop heavy but brief summer rainfall.

In October, the dry season sets in across much of Florida (starting early in the month in northern Florida and near the end of the month in deep southern Florida) and lasts until late April in most years. Fronts from mid-latitude storms north of Florida occasionally pass through northern and central parts of the state which bring light and brief winter rainfall. Mid and late winter can become severely dry in Florida. In some years the dry season becomes quite severe and water restrictions are imposed to conserve water. While most areas of Florida do not experience any type of frozen precipitation, northern Florida can see fleeting snow or sleet a few times each decade.

The Gulf Stream running through the Florida Straits and then north off the Florida East Coast keeps temperatures moderate a few miles inland from around Stuart on the east coast to Ft. Myers on the west side of the state year round, with few extremes in temperature. The tropical ocean current also provides warm sea surface temperatures, giving Florida beaches the warmest ocean surf waters on the United States mainland. Florida's geography also makes it vulnerable to the effects of climate change, both in the intensification of extreme weather such as intensified hurricanes as well as coastal flooding and other effects of sea level rise. Citation?

Pressure

The low pressure measured from an extratropical cyclone was 28.84 inches/976.7 hPa during the Storm of the Century (1993).[2] From a tropical cyclone, the lowest pressure measured was 26.35 inches/892 hPa in the Florida Keys during the Labor Day Hurricane of 1935.[3] The highest known pressure measured statewide was 30.74 inches/1041.1 hPa in Tallahassee on February 5, 1996 and January 4, 1979.[2]

Wind

Over the winter prevailing winds are out of the north across the panhandle south to near Orlando, but are variable in the rest of the state. The summer season sees generally east and southeast winds across the peninsula. During the summer months, the average wind pattern implies a surface ridge axis which normally lies across central Florida, with easterly winds from Tampa southward and southwest winds across northern Florida. The peak wind gust during the 1930 through 1997 period was 115 miles per hour (100 kn) at Miami International Airport during Hurricane Andrew.[4]

African dust outbreaks

In July the trade winds south of the northward-moving subtropical ridge expand northwestward into Florida. On occasion, dust from the Sahara moving around the southern periphery of the ridge moves into the state, suppressing rainfall and changing the sky from a blue to a white appearance and leads to an increase in red sunsets. Its presence negatively impacts air quality across the Southeastern United States during the summer, by adding to the count of airborne particulates. This is in sharp contrast to the normally clean air over Florida and the southeastern USA, which on average is the cleanest air in the USA.[5] Over 50% of the African dust that reaches the United States affects Florida.[6] Since 1970, dust outbreaks have worsened due to periods of drought in Africa. There is a large variability in the dust transport to the Caribbean and Florida from year to year.[7] Dust events are possibly linked to a decline in the health of coral reefs across the Caribbean and Florida, primarily since the 1970s.[8]

Winter

On average, Florida has the mildest winters in the Continental United States. Average lows range from 65 °F (18 °C) in Key West to near 41 °F (5 °C) degrees Fahrenheit at Tallahassee, while daytime highs range from 64 °F (18 °C) at Tallahassee to 77 °F (25 °C) at Miami.[9][10] Predominant tropical easterly winds across central and southern Florida keep temperatures warm during the winter. Occasional strong cold fronts move southward down the peninsula with freezing or near freezing temperatures on a few nights into inland areas of central Florida every few years. A few times each decade Miami might see a winter night fall below 45 °F (7 °C). El Niño winters tend to be cooler due to increased cloud cover, but tend to have fewer freezes.[11]

Four hardiness zones exist. USDA zone 11b with average extreme annual lows between 45 to 50 °F (7 to 10 °C) is found from Key West to Marathon and 11a, 40 to 45 °F (4 to 7 °C), in the remaining keys and Miami Beach. Zone 10b is found in coastal South Florida and much of the Everglades where annual extreme low temperatures range from 35 to 40 °F (2 to 4 °C). Zone 10a, 30 to 35 °F (−1 to 2 °C) is found in the rest of South Florida, and in certain coastal regions as far north as St.Petersburg on the west coast and roughly Vero Beach on the east coast mainland. Next is zone 9b, 25 to 30 °F (−4 to −1 °C), across interior central Florida, changing over to 9a, 20 to 25 °F (−7 to −4 °C), just north of Orlando. The coolest, zone 8b, is located in northwestern Florida from roughly Gainesville and northwest including Tallahassee. Low temperatures range from 15 to 20 °F (−9 to −7 °C). Formally, there exist very small isolated areas near the Georgia border classified as zone 8a with extreme low averages of around 14.9°F.[12][13]

Florida has experienced 12 major freezes. This includes four "impact" freezes, sufficiently severe to kill entire groves of citrus trees, resulting in a noticeable economic effect on citrus growers, prompting them to shift groves further southward. These impact freezes are indicated by asterisks in the following: Great Freeze of 1894-5*, February 13–14, 1899, February 2–6, 1917, December 12–13, 1934, January 1940, December 12–13, 1957, December 12–13, 1962*, January 18–20, 1977, January 12–14, 1981, December 24–25, 1983*, January 20–22, 1985, and December 22–26, 1989*.[14]

Despite being the mildest on average, the winter climate was a crucial contributing factor of the Challenger disaster on January 28, 1986 in which overnight temperatures at Titusville, adjacent to the Kennedy Space Center, had dropped as low as 24 °F (−4 °C)[15] and were still below freezing at 28.0 to 28.9 °F (−2.2 to −1.7 °C) on launch day. The severe cold had caused the O-Rings on the right-side SRB to crack as they only had a redline tolerance of 39 °F (4 °C).

Summer

During the summer, minimal temperatures range from near 70 °F (21 °C) in northern Florida to near 80 °F (27 °C) in the Keys. High temperatures during the summer average in the lower 90s Fahrenheit statewide.[16] Heat index can easily reach 103-110 degrees. Relief from the heat during the summer comes in the form of afternoon and evening thunderstorm activity, late morning and afternoon sea breezes off the relatively cooler ocean, and during the passage of a tropical cyclone. The record high temperature for the state is 109 °F (43 °C) at Monticello in 1931.[17]

Fog

Like the remainder of the Southeastern United States, Florida has a winter maximum in dense fog conditions. Unlike the remainder of the region, the maximum in Florida contains roughly half of the annual occurrences per year, on average. Its summer minimum is less than the remainder of the Southeast. The annual number of heavy fog days (with visibility of .25 miles (0.40 km) or less) has ranged from 50 in Tallahassee, to 1 in Key West, the least foggy region in the state. The two types of fog that are most common in Florida are advection and radiational. Fog can be hazardous to early morning commuters. On January 9, 2008, when fog on Interstate 4 combined with smoke from a nearby fire, visibility was reduced to nearly zero. As a result, five individuals died in a 70-car pileup.[18][19]

Precipitation

Averages

Statewide, the highest rainfall amounts occur during the summer months. In northern Florida, there is a weak winter secondary maximum while statewide the driest months of the year are during the spring.[16] During El Niño, Florida sees greater rainfall between November and March.[11] Due to the lack of the secondary maximum across the peninsula, a distinct dry season is seen in the averages from winter through spring. This dry season provokes brush fires annually as temperatures rise during the late spring, before they fade during early June as the rainy season gets underway.

Extremes

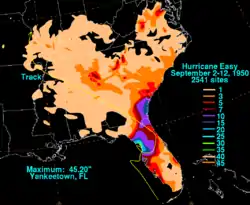

The heaviest rainfall to occur in 24 hours was measured in Yankeetown during Hurricane Easy (1950), 38.70 inches (983 mm). This is also the highest known point storm total maximum related to any tropical cyclone which has impacted Florida,[20] and by itself would be the highest known rainfall total for any month from any location within Florida. This rainfall amount remained the national 24-hour rainfall record until Tropical Storm Claudette (1979).[21] Heavy rainfall events have fallen due to stalled fronts near the state as well, and occur during the March through May and October through November timeframe.

The wettest month recorded at a Florida climate station was during May 1891 when Gainesville, Florida received 30.90 inches (785 mm).[22] The wettest year on record for a Florida climate station was during 1879 when 127.24 inches (3,232 mm) fell at Pensacola, Florida.[23] The driest year for a climate station statewide was during 1974 when only 19.99 inches (508 mm) fell at Key West.[24]

One of the worst years for wildfires was in 1998, at the end of an El Nino cycle. 480 wildfires consumed 500,000 acres (2,000 km2) statewide.[25] In 2010, the National Weather Service issued more fire alerts in Florida than anywhere else in the nation.[26]

A statewide drought began in November 2005, one month after Hurricane Wilma's passage through the state, and persisted until 2009.[27] The previous significant drought occurred in 2000, which was the state's driest year on record.[28]

Snowfall

Snowfall is rare in Florida. The earliest recorded occurrence of snow or sleet occurred in 1774 in the far northern portion of the state.[29] The latest occurrence of snow or sleet fell on January 3, 2018, as a winter storm brought snow flurries in Tallahassee and northern portions of the state.[30]

The state record for snowfall is 5 inches (13 cm), set in northern Florida during January 1800, though some debate exists about the accuracy.[31] The earliest in the season that frozen precipitation has fallen was during the Late November 2006 Nor'easter on November 21 across central Florida.[32] The latest in the season that snow or sleet has fallen was on April 8, 2007. Snow flurries have been reported in the air (not on the ground) as far south as Homestead, during a January 19, 1977 event.[33]

Thunderstorms

Florida reports more thunderstorms than any other US state. Some places report in excess of 90 thunderstorm days per year, making Florida one of the most thundery regions outside of the tropics. Florida receives the highest density of lightning strikes within the United States. Several deaths per year are blamed on lightning, making lightning one of the deadliest weather-related phenomenon in the state. However, since 1992, the number of lightning deaths has been slowly dropping despite a rising population, suggesting that lightning awareness programs are effective. The most likely targets of lightning strikes are construction workers and others who work outside, though 12 percent of the cases occurred indoors to people using electronic devices. Severe thunderstorms can sometimes produce hail, very strong straight line winds and tornadoes. Very heavy rainfall from thunderstorms can result in flash flooding. Thunderstorms occur most often during the summer but can occur at any time of the year.[34]

Tornadoes

There are more tornadoes per square mile in Florida than any other state.[35][36] However, these tornadoes tend to be much weaker and short-lived than in other states like the Midwest or Great Plains. Strong tornadoes do occasionally form in Florida, usually in conjunction with a cold frontal passage in the winter or spring. A total of 42 people died in February 1998 from the deadliest such tornado outbreak in Central Florida, which occurred during the nighttime hours.[37]

While tornadoes in the Midwest are more severe, a higher rate of deaths are experienced in Florida, and Brevard County, specifically, due to higher population density and quantity of manufactured homes.[38]

Tropical cyclones

The earliest in the year a tropical cyclone has struck the sunshine state was the Groundhog Day Tropical Storm in 1952. The latest impact was from a hurricane which struck near Tampa on December 1, 1925. The strongest hurricane to strike Florida was the Labor Day Hurricane of 1935. Hurricane Easy in 1950 produced the wettest known point total from any tropical cyclone.[20] The record number of hurricane strikes on the state in one season is four in 2004.[39] Hurricanes typically spawn tornadoes within their northeast quadrant.[40]

Tropical cyclones have affected Florida in every month of the year but March. Nearly one-third of the cyclones affected the state in September, and nearly three-fourths of the storms affected the state between August and October, which coincides with the peak of the hurricane season. Portions of the coastline have the lowest return period, or the frequency at which a certain intensity or category of hurricane can be expected within 86 miles (138 km) of a given location, in the country. Monroe County was struck by 26 hurricanes since 1926, which is the greatest total for any county in the United States.[41]

Effect of climate cycles

El Niño has the following effects on Florida climate: above average rainfall in the spring.[25] This is followed by wildfire threat when rain dries up. Northern Florida is more susceptible to severe weather; below normal temperatures, increased number of low pressure systems in the Gulf of Mexico during the winter, and "almost always" reduces the frequency of storms and hurricanes.[42]

La Niña has the following effects: often dry conditions prevail in late fall, winter and early spring, increased risk of wildfires in spring and summer months, the temperatures average slightly above normal, and the chance of hurricane activity increases substantially.[42]

Long term forecasts are made based on these effects. However, they are easily overridden, in winter, by the Arctic oscillation and North Atlantic oscillations, which can only be predicted about two weeks in advance.[43] These can drop the temperature noticeably from seasonal norms.

Climates of selected Florida cities

The climate regime for much of the state is humid subtropical (Köppen Cfa), though portions of the Gold Coast of southeast Florida, as well as all of the Florida Keys, qualify as tropical wet-and-dry (Köppen Aw). A narrow eastern part of the state including Orlando and Jacksonville receives between 2,400 and 2,800 hours of sunshine annually. The rest of the state, including Miami, receives between 2,800 and 3,200 hours annually.[44]

| Pensacola, Florida | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tallahassee, Florida | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Jacksonville, Florida | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Orlando, Florida | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tampa, Florida | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Miami, Florida | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Key West, Florida | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

References

- Köppen Classification Map, clearly showing South Florida has a true tropical climate (image will take a few seconds to load)

- National Weather Service Forecast Office Tallahassee, Florida. Tallahassee Weather Extremes. Retrieved on June 3, 2007. Archived October 14, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Eric. S. Blake, Edward N. Rappaport, and Christopher W. Landsea. The Deadliest, Costliest, and Most Intense United States Tropical Cyclones from 1851 to 2006 (AND OTHER FREQUENTLY REQUESTED HURRICANE FACTS). Retrieved on June 3, 2007.

- National Climatic Data Center. Climatic Wind Data for the United States. Retrieved on June 2, 2007. Archived June 13, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Science Daily. African Dust Called A Major Factor Affecting Southeast U.S. Air Quality. Retrieved on June 10, 2007.

- Science Daily. Microbes And The Dust They Ride In On Pose Potential Health Risks. Retrieved on June 10, 2007.

- Usinfo.state.gov. Study Says African Dust Affects Climate in U.S., Caribbean. Archived June 20, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on June 10, 2007.

- U. S. Geological Survey. Coral Mortality and African Dust. Retrieved on June 10, 2007.

- Southeast Regional Climate Center. Tallahassee WSO AP Averages from 1948-2005. Archived March 1, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on June 2, 2007.

- Southeast Regional Climate Center. Key West WSO AP Averages from 1948-2005. Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on June 2, 2007.

- South Florida Water Management District. EL NINO IN SOUTH FLORIDA. Retrieved on June 2, 2007. Archived September 16, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- https://planthardiness.ars.usda.gov/PHZMWeb/InteractiveMap.aspx

- Kridler, Chris (March 5, 2011). "Freeze frazzled? Seek hardier plants". Florida Today. Melbourne, Florida. pp. 1D.

- "Timeline of major Florida freezes". Florida Today. Melbourne, Florida. January 15, 2017. pp. 14A. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- "National Weather Service Climate". w2.weather.gov.

Select 'Titusville, FL'

- Southeast Regional Climate Center. Historical Climate Summaries for Florida. Retrieved on June 2, 2007.

- National Climatic Data Center. "State Climate Extremes Committee (SCsEC)". Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- Gloria Forthun, M. B. Johnson, W. G. Schmitz, and J. Blume.Trends in Fog Frequency and Duration in the Southeast United States. Retrieved on June 7, 2007.

- Michael Mogil and Kristen L. Seaman. Florida's Climate and Weather. Retrieved on 2012-16-03.

- David Roth. Tropical Cyclone Point Maxima. Retrieved on June 2, 2007.

- David Roth. Hurricane Easy (1950) Rainfall Graphic. Retrieved on June 2, 2007.

- Florida Climate Center. Gainesville Precipitation Data. Retrieved on June 2, 2007.

- Florida Climate Center. Pensacola Precipitation Data. Retrieved on June 2, 2007.

- Florida Climate Center. Key West Precipitation Data. Retrieved on June 2, 2007.

- Waymer, Jim (March 11, 2010). "Casualties of cold enhance fire fear". Melbourne, Florida: Florida Today. pp. 3A. Archived from the original on March 14, 2010.

- Knapp, Andrew (February 28, 2011). "Wildfire alerts get stricted". Florida Today. Melbourne, Florida. pp. 1A.

- Travis Reed.Drought Saps Fla. Growers, Golf Courses Retrieved on June 2, 2007.

- NOAA. SEVERE DROUGHT CONDITIONS/FIRE DANGER LIKELY TO PERSIST THROUGHOUT CENTRAL FLORIDA. Archived September 29, 2006, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on June 2, 2007.

- T. Frederick Davis (1908). "Climatology of Jacksonville, Fla. and Vicinity" (PDF). U.S. Weather Bureau. Retrieved March 9, 2008.

- reports, Staff and wire. "How cold is it? Snow is falling in Florida". sun-sentinel.com.

- George Winterling (December 4, 2003). Snow on the First Coast. Archived June 12, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 2007-01-22.

- Local6.com. Snow Falls In Central Florida. Archived September 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on November 26, 2006.

- National Weather Service Forecast Office Tallahassee, Florida. Florida's Top 10 Weather Events of the 20th Century. Retrieved on June 3, 2007. Archived October 14, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Charles H. Paxton, J. Colson and N. Carlisle (2008). "P2.13 Florida lightning deaths and injuries 2004-2007". American Meteorological Society. Retrieved September 5, 2009.

- "Top Ten Tornado Lists", tornadoproject.com, archived from the original on February 4, 2012

- Average Annual Number of Tornadoes, 1991-2010. Downloaded Sunday, 4 August 2013 18:25:05 EDT. Last Updated Monday, 20 May 2013 10:45:01 EDT. From National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

- United States Department of Commerce (June 1998). "Service Assessment: Central Florida Tornado Outbreak February 22–23, 1998" (PDF). National Weather Service. Retrieved September 5, 2009.

- "Study: Florida #1 In Tornadoes and Deaths". Brevard Times. Cocoa Beach, Florida. June 16, 2014. Archived from the original on March 10, 2016.

- National Hurricane Center. Atlantic Tracks File 1851-2006. Retrieved on June 2, 2007.

- Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division (October 4, 2006). "Frequently Asked Questions: Are TC tornadoes weaker than midlatitude tornadoes?". NOAA. Archived from the original on September 14, 2009. Retrieved July 25, 2006.

- National Hurricane Center (2006). "Tropical Cyclone Climatology". Retrieved October 2, 2007.

- Florida Disaster Management accessed March 9, 2008 Archived December 9, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Rice, Doyle (December 28, 2010). "Winter "wild card" in play". Melbourne, Florida: Florida Today. pp. 4A.

- "united states annual sunshine map". HowStuffWorks, Inc. Archived from the original on April 29, 2011. Retrieved March 14, 2011.

- "Pensacola Climate Normals". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

- "Tallahassee Climate Normals". Florida Climate Center.

- "Jacksonville Climate Normals". Florida Climate Center.

- "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

- "Tampa Climate Normals". Florida Climate Center. Archived from the original on June 19, 2011.

- "Miami Climate Normals". Florida Climate Center.

- "Key West Climate Normals". Florida Climate Center.