Climate of North Carolina

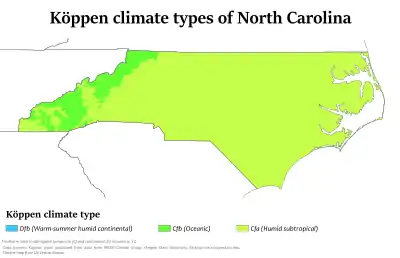

North Carolina's climate varies from the Atlantic coast in the east to the Appalachian Mountain range in the west. The mountains often act as a "shield", blocking low temperatures and storms from the Midwest from entering the Piedmont of North Carolina.[1]

Most of the state has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification Cfa), except in the higher elevations of the Appalachians which have a subtropical highland climate (Köppen Cfb).

The USDA hardiness zones for the state range from zone 5a (-20 °F to -15 °F) in the mountains to zone 8b (15 °F to 20 °F) along the coast.[2] For most areas in the state, the temperatures in July during the daytime are approximately 90 °F (32 °C). In January the average temperatures range near 50 °F (10 °C). (However, a polar vortex or "cold blast" can significantly bring down average temperatures, seen in the winters of 2014 and 2015.)[3]

| Building | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asheville | 46/26 | 50/28 | 58/35 | 66/42 | 74/51 | 80/58 | 83/63 | 82/62 | 76/55 | 67/43 | 57/35 | 49/29 |

| Cape Hatteras | 54/39 | 55/39 | 60/44 | 68/52 | 75/60 | 82/68 | 85/73 | 85/72 | 81/68 | 73/59 | 65/50 | 57/43 |

| Charlotte | 51/32 | 56/34 | 64/42 | 73/49 | 80/58 | 87/66 | 90/71 | 88/69 | 82/63 | 73/51 | 63/42 | 54/35 |

| Greensboro | 47/28 | 52/31 | 60/38 | 70/46 | 77/55 | 84/64 | 88/68 | 86/67 | 79/60 | 70/48 | 60/39 | 51/31 |

| Raleigh | 50/30 | 54/32 | 62/39 | 72/46 | 79/55 | 86/64 | 89/68 | 87/67 | 81/61 | 72/48 | 62/40 | 53/33 |

| Wilmington | 56/36 | 60/38 | 66/44 | 74/51 | 81/60 | 86/68 | 90/72 | 88/71 | 84/66 | 76/54 | 68/45 | 60/38 |

Precipitation

There is an average of forty-five inches of rain a year (fifty inches in mountainous regions). July storms account for much of this precipitation. As much as 15% of the rainfall during the warm season in the Carolinas can be attributed to tropical cyclones.[4] Mountains usually see some snow in the fall and winter.[1] Moist winds from the southwest drop an average of 80 inches (2,000 mm) of precipitation on the western side of the mountains, while the northeast-facing slopes average less than half that amount.[5]

| Average monthly precipitation | |||||||||||||

| City | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asheville[6] | 2.6 inches (66 mm) | 3.1 inches (79 mm) | 4 inches (100 mm) | 3.3 inches (84 mm) | 2.9 inches (74 mm) | 3.5 inches (89 mm) | 3.4 inches (86 mm) | 4 inches (100 mm) | 3.1 inches (79 mm) | 2.7 inches (69 mm) | 2.6 inches (66 mm) | 2.7 inches (69 mm) | 38.1 inches (970 mm) |

| Cape Hatteras[7] | 5.6 inches (140 mm) | 4.1 inches (100 mm) | 4.6 inches (120 mm) | 3.2 inches (81 mm) | 3.8 inches (97 mm) | 4.2 inches (110 mm) | 4.9 inches (120 mm) | 6.4 inches (160 mm) | 5.3 inches (130 mm) | 5.3 inches (130 mm) | 4.9 inches (120 mm) | 4.5 inches (110 mm) | 56.9 inches (1,450 mm) |

| Charlotte[8] | 3.7 inches (94 mm) | 3.7 inches (94 mm) | 4.6 inches (120 mm) | 3 inches (76 mm) | 3.6 inches (91 mm) | 3.5 inches (89 mm) | 3.8 inches (97 mm) | 4.1 inches (100 mm) | 3.3 inches (84 mm) | 3.2 inches (81 mm) | 3.1 inches (79 mm) | 3.3 inches (84 mm) | 43 inches (1,100 mm) |

| Greensboro[9] | 3.3 inches (84 mm) | 3.3 inches (84 mm) | 3.8 inches (97 mm) | 3.2 inches (81 mm) | 3.6 inches (91 mm) | 3.8 inches (97 mm) | 4.4 inches (110 mm) | 4.1 inches (100 mm) | 3.3 inches (84 mm) | 3.4 inches (86 mm) | 2.9 inches (74 mm) | 3.2 inches (81 mm) | 42.3 inches (1,070 mm) |

| Raleigh[10] | 3.5 inches (89 mm) | 3.5 inches (89 mm) | 3.7 inches (94 mm) | 2.8 inches (71 mm) | 3.8 inches (97 mm) | 3.6 inches (91 mm) | 4.4 inches (110 mm) | 4.4 inches (110 mm) | 3.1 inches (79 mm) | 3 inches (76 mm) | 2.9 inches (74 mm) | 3.1 inches (79 mm) | 41.8 inches (1,060 mm) |

| Wilmington[11] | 3.6 inches (91 mm) | 3.5 inches (89 mm) | 4.3 inches (110 mm) | 2.9 inches (74 mm) | 4.3 inches (110 mm) | 5.4 inches (140 mm) | 7.9 inches (200 mm) | 7 inches (180 mm) | 5.6 inches (140 mm) | 3.3 inches (84 mm) | 3.3 inches (84 mm) | 3.5 inches (89 mm) | 55 inches (1,400 mm) |

Snow

Snow in North Carolina is seen on a regular basis in the mountains. North Carolina averages 5 inches (130 mm) of snow a year. However, this also varies greatly across the state. Along the coast, most areas register less than 2 inches (51 mm) per year while the state capital, Raleigh averages 7.5 inches (190 mm). Farther west in the Piedmont-Triad, the average grows to approximately 9 inches (230 mm). The Charlotte area averages approximately 6.5 inches (170 mm). The town of Boone, North Carolina, located at an elevation of 3,333 feet in the northwestern part of the state, averages approximately 35 inches of snow a year. The mountains in the west act as a barrier, preventing most snowstorms from entering the Piedmont. When snow does make it past the mountains, it is usually light and is seldom on the ground for more than two or three days. However, several storms have dropped 18 inches (460 mm) or more of snow within normally warm areas. The 1993 Storm of the Century that lasted from March 11 to March 15 affected locales from Canada to Central America, and brought a significant amount of snow to North Carolina. Newfound Gap received more than 36 inches (0.91 m) of snow with drifts more than 5 feet (1.5 m), while Mount Mitchell measured over 4 feet (1.2 m) of snow with drifts to 14 feet (4.3 m).[12] Most of the northwestern part of the state received somewhere between 2 feet (0.61 m) an 3 feet (0.91 m) of snow.

Another significant snowfall hit the Raleigh area in January 2000 when more than 20 inches (510 mm) of snow fell.[13] There was also a heavy snowfall totaling 18 inches (460 mm) that hit the Wilmington area on December 22–23, 1989. This storm affected only the Southeastern US coast, as far south as Savannah, GA, with little to no snow measured west of I-95. Most big snows that impact areas east of the mountains come from extratropical cyclones which approach from the south across Georgia and South Carolina and move off the coast of North or South Carolina. These storms typically throw Gulf or Atlantic moisture over cold Arctic air at ground level, usually propelled southward from Arctic high pressure over the Northeastern or New England states. If the storms track sufficiently far to the east, snow will be limited to the eastern part of the state (as with the December 22–23, 1989 storm). If the cyclones travel close to the coast, warm air will get pulled into eastern North Carolina due to increasing flow off the milder Atlantic Ocean, bringing a rain/snow line well inland with heavy snow restricted to the Piedmont, foothills and mountains, as with the January 22, 1987 storm. If the storm tracks inland into eastern North Carolina, the rain/snow line ranges between Raleigh and Greensboro.[14]

| Average monthly snowfall | |||||||||||||

| City | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asheville[6] | 4.6 inches (12 cm) | 4.6 inches (12 cm) | 3 inches (7.6 cm) | 0.7 inches (1.8 cm) | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.7 inches (1.8 cm) | 2 inches (5.1 cm) | 15.6 inches (40 cm) |

| Cape Hatteras[7] | 0.4 inches (1.0 cm) | 0.6 inches (1.5 cm) | 0.4 inches (1.0 cm) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.6 inches (1.5 cm) | 2 inches (5.1 cm) |

| Charlotte[8] | 2 inches (5.1 cm) | 1.7 inches (4.3 cm) | 1.2 inches (3.0 cm) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.1 inches (0.25 cm) | 0.5 inches (1.3 cm) | 5.5 inches (14 cm) |

| Greensboro[9] | 3.1 inches (7.9 cm) | 2.5 inches (6.4 cm) | 1.7 inches (4.3 cm) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.1 inches (0.25 cm) | 1.2 inches (3.0 cm) | 8.6 inches (22 cm) |

| Raleigh[10] | 2.2 inches (5.6 cm) | 2.6 inches (6.6 cm) | 1.3 inches (3.3 cm) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.1 inches (0.25 cm) | 0.8 inches (2.0 cm) | 7 inches (18 cm) |

| Wilmington[11] | 0.4 inches (1.0 cm) | 0.5 inches (1.3 cm) | 0.4 inches (1.0 cm) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.6 inches (1.5 cm) | 1.9 inches (4.8 cm) |

Tropical cyclones

Located along the Atlantic Coast, many hurricanes that come up from the Caribbean Sea make it up the coast of eastern America, passing by North Carolina.

On October 15, 1954, Hurricane Hazel struck North Carolina, at that time it was a category 4 hurricane within the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale. Hazel caused significant damage due to its strong winds. A weather station at Oak Island reported maximum sustained winds of 140 miles per hour (230 km/h), while in Raleigh winds of 90 miles per hour (140 km/h) were measured. The hurricane caused 19 deaths and significant destruction. One person at Long Beach claimed that "of the 357 buildings that existed in the town, 352 were totally destroyed and the other five damaged". Hazel was described as "the most destructive storm in the history of North Carolina" in a 1989 report.[15]

In 1996, Hurricane Fran made landfall in North Carolina. As a category 3 hurricane, Fran caused a great deal of damage, mainly through winds. Fran's maximum sustained wind speeds were 115 miles per hour (185 km/h), while North Carolina's coast saw surges of 8 feet (2.4 m) to 12 feet (3.7 m) above sea level. The amount of damage caused by Fran ranged from $1.275 to $2 billion in North Carolina.[15]

Rain

Heavy rains accompany tropical cyclones and their remnants which move northeast from the Gulf of Mexico coastline, as well as inland from the western subtropical Atlantic ocean. Over the past 30 years, the wettest tropical cyclone to strike the coastal plain was Hurricane Floyd of September 1999, which dropped over 24 inches (610 mm) of rainfall north of Southport. Unlike Hazel and Fran, the main force of destruction was from precipitation. Before Hurricane Floyd reached North Carolina, the state had already received large amounts of rain from Hurricane Dennis less than two weeks before Floyd. This saturated much of the Eastern North Carolina soil and allowed heavy rains from Hurricane Floyd to turn into floods. Over 35 people died from Floyd.[15] In the mountains, Hurricane Frances of September 2004 was nearly as wet, bringing over 23 inches (580 mm) of rainfall to Mount Mitchell.[16]

Severe weather

In most years, the greatest weather-related economic loss incurred in North Carolina is due to severe weather spawned by summer thunderstorms. These storms affect limited areas, with their hail and wind accounting for an average annual loss of over US$5 million.[17]

North Carolina averages 31 tornadoes a year with May seeing the most tornadoes on average a month with 5. June, July and August all have an average of 3 tornadoes with an increase to 4 average tornadoes a month in September. It is through September and into early November when North Carolina can typically expect to see that smaller, secondary, severe weather season. While severe weather season is technically from March through May, tornadoes have touched down in North Carolina in every month of the year.[18] On November 28, 1988, an early morning F4 tornado smashed across northwestern Raleigh, continuing 84 miles further, killing 4 and injuring 157.[19] On February 6, 2020, severe storms hit North Carolina, with a tornado beginning in Rowan County, north of Charlotte. as it travelled north, wind speeds picked up to 30 mph.[20] By 4pm, 100 000 people were without power and flash flood warnings were hitting areas in the North and Northwest with this floodwatch staying in full effect until the following Thursday.[20]

Changes

The North Carolina coastline is expected to rise between one and four feet in the next century due to a combination of warming oceans, melting ice, and land subsidence.[21] Temperatures in North Carolina have risen. Over the last 100 years, the average temperature in Chapel Hill has gone up 1.2 °F (0.7 °C) and precipitation in some parts of the state has increased by 5 percent.[22] Around the year 2080, "temperatures are likely to rise above 95°F approximately 20 to 40 days per year in most of the state, compared with about 10 days per year" in 2016.[21]

Seasonal conditions

Winter

In winter, North Carolina is somewhat protected by the Appalachian Mountains to the west. Cold fronts from Canada are typically reduced in intensity by the mountains. However, occasionally cold air can move from the north or northeast, east of the Appalachian Mountains, from Arctic high pressure systems that settle over the Northeastern or New England states. Other polar and Arctic outbreaks can cross the mountains and force temperatures to drop to about 12 °F (−11 °C) in central North Carolina. Still, temperatures below zero degrees Fahrenheit are extremely rare outside of the mountains. The coldest ever recorded temperature in North Carolina was −34 °F (−37 °C) on January 21, 1985, at Mount Mitchell. The winter temperatures on the coast are milder due to the warming influence of the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf Stream.[23] The average ocean temperature in Southport in January is still higher than the average ocean temperature in Maine during July.[23] Snow is common in the mountains, although many ski resorts use snowmaking equipment to make sure there is always snow on their land.[23] North Carolina's relative humidity is highest in the winter.[23]

Spring

Tornadoes are most likely in the spring. Major tornado outbreaks affected parts of eastern North Carolina on March 28, 1984, and April 16, 2011. The month of May experiences the greatest rise in temperatures. During the spring, there are warm days and cool nights in the Piedmont. Temperatures are somewhat cooler in the mountains and warmer, particularly at night, near the coast.[23] North Carolina's humidity is lowest in the spring.[23]

Summer

North Carolina experiences high summer temperatures. Sometimes, cool, dry air from the north will invade North Carolina for brief periods of time, with temperatures quickly rebounding.[24] It remains colder at high elevations, with the average summer temperature in Mount Mitchell lying at 68 °F (20 °C). Morning temperatures are on average 20 °F (12 °C) lower than afternoon temperatures, except along the Atlantic Coast.[23] The largest economic loss from severe weather in North Carolina is due to severe thunderstorms in the summer, although they usually only hit small areas.[23] Tropical cyclones can impact the state during the summer as well. Fogs are also frequent in the summer.

Fall

Fall is the most rapidly changing season temperature wise, especially in October and November.[23] Tropical cyclones remain a threat until late in the season. The Appalachian Mountains are frequently visited at this time of year, due to the leaves changing color in the trees.[23]

Southern Oscillation

During El Niño events, winter and early spring temperatures are cooler than average with above average precipitation in the central and eastern parts of the state and drier weather in the western part. La Niña usually brings warmer than average temperatures with above average precipitation in the western part of the state while the central and coastal regions stay drier than average.

See also

References

- North Carolina Department of the Secretary of State. North Carolina Climate & Geography. Retrieved on 2008-01-13.

- "North Carolina USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map". plantmaps.com plantmaps. Retrieved December 12, 2018.

- U.S. Travel Weather. North Carolina Weather. Retrieved on 2008-01-13. Archived January 29, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- David B. Knight Robert E. Davis. Climatology of Tropical Cyclone Rainfall in the Southeastern United States. Retrieved on 2008-02-29.

- City-Data.com North Carolina - Climate Retrieved on 2008-02-09.

- Weatherbase. Asheville, North Carolina Weather. Retrieved on 2008-02-08.

- Weatherbase. Cape Hatteras, North Carolina Weather. Retrieved on 2008-02-08.

- Weatherbase. Charlotte, North Carolina Weather. Retrieved on 2008-02-08.

- Weatherbase. Greensboro, North Carolina Weather. Retrieved on 2008-02-08.

- Weatherbase. Raleigh, North Carolina Weather. Retrieved on 2008-02-08.

- Weatherbase. Wilmington, North Carolina Weather. Retrieved on 2008-02-08.

- Intellicast.com. "MARCH IN THE NORTHEAST". Retrieved 2008-02-09.

- Environmental Modeling Center. EMC MODEL GUIDANCE FOR THE BLIZZARD of 2000. Retrieved on 2008-02-09.

- Keeter, Kermit K.; Businger, Steven; Lee, Laurence G.; Waldstreicher, Jeff S. (March 1995). "Winter Weather Forecasting throughout the Eastern United States. Part III: The Effects of Topography and the Variability of Winter Weather in the Carolinas and Virginia". Weather and Forecasting. 10 (1): 42–60. Bibcode:1995WtFor..10...42K. doi:10.1175/1520-0434(1995)010<0042:WWFTTE>2.0.CO;2.

- State Climate Office of North Carolina. Research on North Carolina Severe Weather. Retrieved on 2008-03-09. Archived December 16, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- Roth, David M; Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. "Tropical Cyclone Rainfall in the Southeastern United States". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Point Maxima. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- State Climate Office of North Carolina. Overview. Archived 2007-12-23 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 2008-03-14.

- http://www4.ncsu.edu/~nwsfo/storage/cases/19881128/

- Price, Mark (6 February 2020). "Storms, high winds, heavy rain through Triangle". The News & Observer. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- "What climate change means for North Carolina" (PDF). EPA. August 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- Duke University. Climate Change and North Carolina Archived September 12, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 2008-01-17.

- State Climate Office of North Carolina. General Summary of N.C. Climate. Archived 2007-12-23 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 2008-01-13.

- NCDC Climate of North Carolina Retrieved on 2008-02-09.