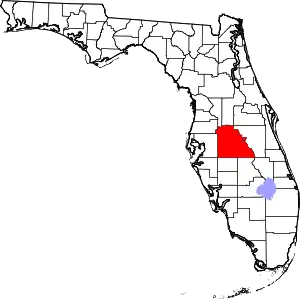

Polk County, Florida

Polk County is a county located in the central portion of the U.S. state of Florida. The county population was 602,095, as of the 2010 census.[2] Its county seat is Bartow,[3] and its largest city is Lakeland.

Polk County | |

|---|---|

Polk County courthouse in Bartow | |

Seal | |

Location within the U.S. state of Florida | |

Florida's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 27°58′N 81°42′W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | February 8, 1861 |

| Named for | James K. Polk |

| Seat | Bartow |

| Largest city | Lakeland |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2,011 sq mi (5,210 km2) |

| • Land | 1,798 sq mi (4,660 km2) |

| • Water | 213 sq mi (550 km2) 10.6%% |

| Population | |

| • Estimate (2019) | 724,777[1] |

| • Density | 382/sq mi (147/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Area code | 863 |

| Congressional districts | 9th, 15th, 17th |

| Website | www |

Polk County comprises the Lakeland–Winter Haven Metropolitan Statistical Area.[4] This MSA is the 87th-most populous metropolitan statistical area and the 89th-most populous primary statistical area of the United States as of July 1, 2012.[5][6]

The center of population of Florida is located in Polk County, near the city of Lake Wales.[7]

Polk County is home to one public university, one state college, and four private universities. One Fortune 500 company, Publix Super Markets, has headquarters in the county.

History

The first people to inhabit the area now called Polk County arrived close to 12,000 years ago during the last ice age as the first paleo-indians following big game southward reached the peninsula of Florida.[8][9]

By this time, the peninsula had gone through several expansions and contractions due to changing sea level; at times the peninsula was much wider than it is today, while at other times it was almost entirely submerged with only a few small islands exposed. These first paleo-indians, nomadic hunter/gatherers who did not establish any permanent settlements, eventually gave way to the "archaic people". These were ancestors of the historic Native Americans who came in contact with the Spaniards when they arrived on the peninsula. These Native Americans thrived on the peninsula. It is estimated that there were more than 250,000 in 1492 when Columbus set sail for the New World. As was common elsewhere in the Americas, contact with Europeans had a devastating effect on the Native Americans. Smallpox, measles, and other diseases, to which the Native Americans had no immunity, caused widespread epidemic and death.[9][10] Those who had not succumbed to diseases such as these were often either killed or enslaved as Spanish explorers and settlers arrived. Within a few hundred years, nearly the entire pre-Columbian population of Polk County had been wiped out.

For around 250 years after Ponce De Leon arrived on the peninsula, the Spanish nominally ruled Florida but established few settlements. In the late 17th century, Florida went through an unstable period in which the French and British ruled the peninsula. By this time, the remnants of early Native Americans joined with refugee Creek Native Americans from Georgia and The Carolinas to form the Seminole Indian Tribe, through a process of ethnogenesis.[9] After the American Revolution, the peninsula briefly reverted to Spanish rule. In 1819, Florida became a U.S. territory as a result of the Adams-Onis Treaty. From the 1830s until 1842, the US conducted the Seminole Wars in an effort to remove the Seminole from the territory. Some were removed to Indian Territory, but others retreated to the Everglades and never surrendered.

While Florida gained statehood in 1845, it was not until 1861 that Polk County was created from the eastern part of Hillsborough County. It was named in honor of former US President James K. Polk,[11] whose 1845 inauguration was on the day after Florida became a state.

Following the Civil War, the county commission established the county seat on 120 acres (0.49 km2) donated in the central part of the county. Bartow, the county seat, was named after Francis S. Bartow, a Confederate colonel from Georgia who was the first Confederate brigade commander to die in battle. Colonel Bartow was buried in Savannah, Georgia with military honors, and promoted posthumously to the rank of Brigadier General. The original name of the town was Fort Blount. Several other towns and counties in the South changed their name to Bartow. The first courthouse built in Bartow was constructed in 1867. It was replaced twice, in 1884 and in 1908. As the third courthouse to stand on the site, the present structure houses the Polk County Historical Museum and Genealogical Library. After the Civil War, some 400 Confederate veterans settled here with families before the end of the century.

Post-Reconstruction era to World War II

In the post-Reconstruction period, black railway workers were among the first African Americans to settle in Polk County, in 1883 south of Lake Wire. The following year they founded St. John's Baptist Church, which also served as the first school for freedmen's children. Other workers arrived for jobs in the phosphate industry. This area became the center of a predominately African-American community later known as Moorehead, after Rev. H.K. Moorehead, called to St. John's in 1906. The community developed its own businesses, professional class, and cultural institutions. Its students had to go to other cities for high school until 1928, when the first upper school to serve blacks was established here.[12]

White violence rose against blacks in the late 19th century in a regionwide effort to establish and maintain white supremacy as Southern states disenfranchised most blacks and imposed Jim Crow. Whites lynched 20 African Americans in Polk County from 1895 to 1921;[13] Three black men, whose names were not recorded, were murdered in a mass lynching on May 25, 1895, accused of rape. While others were killed for alleged crimes (never proven), one black man was lynched for supposedly insulting a white woman. The man, Henry Scott was a porter on a train from Lakeland to Bartow. While he was preparing a berth for one woman on May 20, 1920, another white woman became angry that he made her wait. She sent a telegram to the next station where he was met by a sheriff, arrested, and then turned over to a mob that shot him 40-t0 times.[14] Columbia County also had 20 such lynching murders; these two counties had the second-highest total of lynchings of African Americans of any county in the state.

In the first few decades of the 1900s, thousands of acres of land around Bartow were purchased by the phosphate industry. The county seat became the hub of the largest phosphate industry in the United States, attracting both immigrants and African-American and white workers from rural areas.[15]

Polk County was the leading citrus county in the United States for much of the 20th century, and even the county seat Bartow has had several large groves. In 1941, the city built an airport northeast of town in the county.[16] The airport was taken over by the federal government during World War II and was the training location for many Army Air Corps pilots during the war. The airport was returned to the city in 1967 and renamed as Bartow Municipal Airport.[16]

Mid-20th century to present

In the 20th century, the Ku Klux Klan revived and was active in Polk County, even after World War II. Klansmen were photographed in hoods and robes in 1958 in a church in Mulberry. During the 1960s violence related to civil rights movement was attributed to the Klan. In 1967, a white man shot and severely wounded a popular African-American high school football player who was integrating Lake Ariana Beach.[13] A Klan group marched in Lakeland in full regalia in 1979, their last public march by the Confederate monument in Munn Park.[13]

Since the late 20th century, growth in Polk County has been driven by its proximity to both the Tampa and Orlando metropolitan areas along the Interstate 4 corridor. Recent growth has been heaviest in Lakeland (closest to Tampa) and the Northeast areas near Haines City (nearest to Orlando). From 1990 to 2000, unincorporated areas grew 25%, while incorporated areas grew only 11%. In addition to cottage communities that have developed for commuters, Haines City has suburban sprawl into unincorporated areas. Despite the impressive growth rate, the unemployment rate of Polk has typically been higher than that of the entire state.[17] For example, in August 2010, the county had an unemployment rate of 13.4%, compared to 11.7% for the entire state.[17]

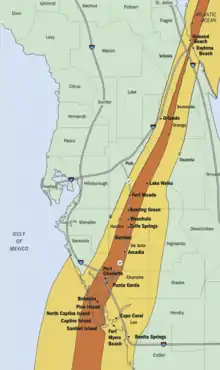

During the 2004 Atlantic hurricane season, three hurricanes, Charley, Frances and Jeanne, all tracked over Polk County, intersecting in a triangle that includes the city of Bartow.[18]

Winter Haven was best known as the home of the Cypress Gardens theme park, which operated from 1936 to September 23, 2009.[19] Legoland Florida has since been built on the site of former Cypress Gardens, and has preserved the botanical garden section. Winter Haven was the location of the first Publix supermarket circa 1930; today Publix's corporate offices are located in Lakeland. Country musician Gram Parsons was from a wealthy family in Winter Haven.

In 2018, the Lakeland City Commission voted to move the Confederate monument, installed in 1910 at Munn Park in Lakeland, to Veterans Memorial Park. This was the location of the original African-American community of Moorehead, which was first settled in 1883. Owners were bought out in 1967 by eminent domain for county civic development of a conference center and the later Veterans Memorial Park. Some members of the black community have objected to the Confederate monument being relocated to the land of what had been their historic community in Lakeland, saying it would be more appropriate to be located in the cemetery with numerous Confederate graves.[12]

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 2,011 square miles (5,210 km2), of which 1,798 square miles (4,660 km2) is land and 213 square miles (550 km2) (10.6%) is water.[20] It is the fourth-largest county in Florida by land area and fifth-largest by total area.

Polk County is within the Central Florida Highlands area of the Atlantic coastal plain, with a terrain consisting of flatland interspersed with gently rolling hills. Part of the Lake Wales Ridge runs through eastern Polk County, which is known for its rolling hills, unique wildlife and plants. The highest elevation in the county is Crooked Lake Sandhill, with the second highest being Iron Mountain, the location of Bok Tower.

Adjacent counties

|

|

|

In addition, at its northeast corner, Polk County touches Orange County at a quadripoint called Four Corners, Florida; Lake and Osceola counties lie between.

Climate

Polk County, like most of Florida, has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa). It lies in the USDA Plant Hardiness Zone 9b, where the average annual minimum temperature is 25-30 °F (-3.9 °C to -1.1 °C).[21] The last measurable snow in the county fell in 1977, but snow flurries and sleet fell on January 8, 2010 over the course of an hour on an exceptionally cold day.[22]

During the summer rainy season from June to September, sea breezes from both coasts move inland, where the moist air is heated and rises to form thunderstorms. On many days, the sea breeze thunderstorms from both coasts will move inland, colliding in Polk County to form especially strong thunderstorms.[23]:589 Polk County is located in the middle of "lightning alley", which has more lightning annually than any region in the United States. Largely due to its size, the county receives the overall highest number of lightning strikes in the area.[23]:590–591

The Green Swamp is prone to fog in winter. In the pre-dawn hours of January 8, 2008, smoke from a prescribed burn contributed to especially dense fog on Interstate 4 that caused a major pileup involving 70 vehicles in ten separate crashes that resulted in five deaths.[24] A 2017 study by the Climate Impact Lab determined that among the 131 U.S. counties with more than 500,000 residents, Polk County would be the most economically impacted (as a percentage of GDP) by climate change by the end of the twenty-first century.[25]

| Climate data for Lakeland (LAL), 1981–2010 normals, extremes 1948–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 87 (31) |

90 (32) |

92 (33) |

95 (35) |

103 (39) |

105 (41) |

102 (39) |

100 (38) |

98 (37) |

96 (36) |

93 (34) |

87 (31) |

105 (41) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 73.6 (23.1) |

76.9 (24.9) |

81.0 (27.2) |

85.7 (29.8) |

90.7 (32.6) |

93.2 (34.0) |

93.9 (34.4) |

94.2 (34.6) |

91.7 (33.2) |

86.6 (30.3) |

79.9 (26.6) |

74.5 (23.6) |

85.2 (29.6) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 50.2 (10.1) |

52.5 (11.4) |

56.2 (13.4) |

60.0 (15.6) |

66.5 (19.2) |

71.7 (22.1) |

72.8 (22.7) |

73.1 (22.8) |

72.1 (22.3) |

66.0 (18.9) |

58.5 (14.7) |

52.3 (11.3) |

62.7 (17.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 20 (−7) |

27 (−3) |

25 (−4) |

35 (2) |

47 (8) |

56 (13) |

64 (18) |

63 (17) |

62 (17) |

42 (6) |

28 (−2) |

20 (−7) |

20 (−7) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.59 (66) |

2.67 (68) |

3.68 (93) |

2.54 (65) |

3.19 (81) |

8.74 (222) |

7.88 (200) |

7.51 (191) |

6.10 (155) |

2.60 (66) |

1.79 (45) |

2.88 (73) |

52.17 (1,325) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.01 in) | 7.8 | 7.4 | 7.8 | 6.4 | 7.5 | 14.4 | 17.1 | 16.8 | 12.4 | 6.9 | 6.4 | 5.9 | 116.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 203.2 | 209.4 | 258.2 | 302.1 | 306.7 | 255.8 | 255.4 | 248.9 | 226.5 | 239.9 | 213.4 | 203.5 | 2,923 |

| Source: [26] | |||||||||||||

Tropical cyclones

The eyes of 12 hurricanes have passed through the county at hurricane strength in recorded history, including Hurricane Irma (2017, category 1), Hurricane Jeanne (2004, category 1), Hurricane Charley (2004, category 2), Hurricane Donna (1960, category 2), Hurricane King (1950, category 1), the 1949 Florida hurricane (category 2), the 1945 Homestead hurricane (category 1), the 1933 Treasure Coast hurricane (category 1), the 1928 Okeechobee hurricane (category 2), Hurricane Four of the 1894 season (category 1), and Hurricane Three of the 1871 season, and Hurricane Eight of the 1859 season (category 1).[27] Additionally, four storms were downgraded from hurricane strength at a location outside the county to tropical storm force at some point within the county and, given the hours between National Hurricane Center updates (modern era) or earlier estimates, it is not clear whether these brought hurricane-force sustained winds to Polk County: Hurricane Frances (2004), Hurricane Erin (1995) Hurricane Two of the 1939 season, and the 1910 Cuba hurricane (category 1).[27] Numerous tropical storms have passed through the county.[27]

Hurricane Charley in 2004—the first of three hurricanes to hit the county in six weeks—is the strongest storm in recent history to pass through the county, mainly impacting the eastern half of the county. The Lake Wales Fire Department recorded an unofficial maximum wind speed of 95 mph (153 km/h) sustained and a gust of 101 mph (163 km/h).[28] The hurricane entered the county south of Fort Meade, shortly after it passed Wauchula (in Hardee County), where a maximum wind gust of 109 mph (175 km/h) was recorded by emergency management officials.[29] The hurricane-force wind field was relatively narrow, with the most intense wind damage being within 10 mi (16 km) of the center of the eye.[30] For example, maximum recorded winds were only 41 kn (76 km/h; 47 mph) sustained and a gust of 54 kn (100 km/h; 62 mph) at Gilbert Airport on the northwest side of the city.[31]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1870 | 3,169 | — | |

| 1880 | 3,181 | 0.4% | |

| 1890 | 7,905 | 148.5% | |

| 1900 | 12,472 | 57.8% | |

| 1910 | 24,148 | 93.6% | |

| 1920 | 38,661 | 60.1% | |

| 1930 | 72,291 | 87.0% | |

| 1940 | 86,665 | 19.9% | |

| 1950 | 123,997 | 43.1% | |

| 1960 | 195,139 | 57.4% | |

| 1970 | 227,222 | 16.4% | |

| 1980 | 321,652 | 41.6% | |

| 1990 | 405,382 | 26.0% | |

| 2000 | 483,924 | 19.4% | |

| 2010 | 602,095 | 24.4% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 724,777 | [1] | 20.4% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[32] 1790–1960[33] 1900–1990[34] 1990–2000[35] 2010–2019[2] | |||

2010 Census

U.S. Census Bureau 2010 Ethnic/Race Demographics:[36][37]

- White (non-Hispanic) (75.2% when including White Hispanics): 64.6%

- Black (non-Hispanic) (14.8% when including Black Hispanics): 14.2%

- Hispanic or Latino of any race: 17.7%

- Asian: 1.6%

- Two or more races: 2.4%

- American Indian and Alaska Native: 0.4%

- Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander: 0.1%[36][37]

- Other Races: 5.5%

In 2010, the largest ancestry groups were:

12.2% German

11.6% American

11.2% English

10.8% Irish

7.6% Mexican

5.8% Puerto Rican

4.1% Italian

2.6% French

2.1% Polish

2.0% Scotch-Irish

1.8% Scottish

1.5% Dutch

1.2% Cuban[36]

There were 227,485 households, out of which 27.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 51.1% were married couples living together, 13.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 30.0% were non-families. 23.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.0% (3.4% male and 7.6% female) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.59 and the average family size was 3.05.[37][38]

In the county, the population was spread out, with 23.5% under the age of 18, 8.8% from 18 to 24, 24.0% from 25 to 44, 25.6% from 45 to 64, and 18.0% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 39.8 years. For every 100 females there were 96.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 93.7 males.[38]

The median income for a household in the county was $43,946, and the median income for a family was $51,395. Males had a median income of $37,768 versus $30,655 for females. The per capita income for the county was $21,881. About 11.5% of families and 15.2% of the population were below the poverty line, including 23.5% of those under age 18 and 8.7% of those aged 65 or over.[39]

In 2010, 10.7% of the county's population was foreign-born, with 37.8% being naturalized American citizens. Of foreign-born residents, 70.4% were born in Latin America, 11.5% were born in Europe, 10.2% born in Asia, 4.9% in North America, 2.6% born in Africa, and 0.4% were born in Oceania.[36]

2000 Census

As of the census of 2000, there were 483,924 people, 187,233 households, and 132,373 families residing in the county. The population density was 258 people per square mile (100/km2). There were 226,376 housing units at an average density of 121 per square mile (47/km2). The racial makeup of the county was 79.58% White (74.6% were Non-Hispanic White),[40] 13.54% Black or African American, 0.38% Native American, 0.93% Asian, 0.04% Pacific Islander, 3.82% from other races, and 1.71% from two or more races. 9.49% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race. In 2000 only 37% of county residents lived in incorporated metropolitan areas.[41]

There were 187,233 households, of which 29.00% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 54.40% were married couples living together, 12.00% had a female householder with no husband present, and 29.30% were non-families. 24.10% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.10% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.52 and the average family size was 2.96.

In the county, the population was spread out, with 24.40% under the age of 18, 8.30% from 18 to 24, 26.40% from 25 to 44, 22.50% from 45 to 64, and 18.30% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 39 years. For every 100 females there were 96.30 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 93.10 males.

The median income for a household in the county was $36,036, and the median income for a family was $41,442. Males had a median income of $31,396, versus $22,406 for females. The per capita income for the county was $18,302. 12.90% of the population and 9.40% of families were below the poverty line. Out of the total population, 19.10% were under the age of 18 and 8.10% were 65 or older.

Languages

As of 2010, 81.80% of all residents spoke English as their first language, while 14.34% spoke Spanish, 0.70% French Creole (mostly Haitian Creole,) and 0.51% of the population spoke French as their mother language.[42] In total, 18.20% of the population spoke languages other than English as their primary language.[42]

Economy

Polk County's economy is supported by a workforce of over 275,000 in 2010.[43] Traditionally, the largest industries in Polk County's economy have been phosphate mining, agriculture, and tourism.[15]

Notable companies headquartered in Polk County include Publix (the employee-owned grocery chain) and Florida's Natural (the agricultural cooperative).

Top employers

The top employers of Polk County are as follows:[44]

- Polk County Public Schools (13,000)

- Publix (11,721)

- Lakeland Regional Health (5,605)

- Walmart (5,100)

- City of Lakeland (2,300)

- GEICO (2,222)

- Polk County Board of County Commissioners (2,200)

- Winter Haven Hospital (2,079)

- Polk County Sheriff's Office (1,955)

- Watson Clinic (1,851)

- Southeastern University (1,557)

- Legoland Florida (1,500)

- The Mosaic Company (1,380)

- Sykes (1,150)

- State Farm Insurance (1,000)

- Amazon (1,000)

- GC Services (1,000)

- Polk State College (932)

- Rooms to Go (900)

- Florida's Natural Growers (645)

- Employers and statistic last updated April 23, 2018

Sports

Polk County is home to professional baseball and basketball teams and boasts a rich history of collegiate sports competition at a number of its institutions of higher learning, including perennial NCAA Division II National Championship contender and titleholder (in multiple sports), Florida Southern College.

Professional baseball, especially major league spring training, was historically a major generator of tourist traffic for Polk County. Today, however, only the Detroit Tigers remain for spring training. Additionally the Class A-Advanced Lakeland Flying Tigers play in Joker Marchant Stadium after spring training.[45]

Professional basketball made its debut in 2017 when The Lakeland Magic took the court in its home venue, RP Funding Center. The team is the NBA G League developmental affiliate of the NBA's Orlando Magic.

College sports are also popular in Polk County. The Florida Southern Moccasins play in NCAA Division II in the Sunshine State Conference.

Government and politics

The executive and legislative powers of the county are vested in the five-member Board of County Commissioners. While the county is divided into five separate districts, each commissioner is elected at-large, countywide,[46] requiring them to gain majority support. Each term lasts for four years, with odd-numbered districts holding elections in presidential election years, and even-numbered districts holding elections two years later. Like all elected officials in the state, county commissioners are subject to recall. The commissioners elect a chairman and vice-chairman annually. The chairman selects the chairs of each committee, who work with the county manager to establish the policies of the board. The commission meets twice a month- generally every other Tuesday. Additional meetings take place as needed, but must be announced per the Florida Sunshine laws.[46] Melony Bell, from Fort Meade, serves as a County Commissioner.

Among the most important duties of the county commission is levying taxes and appropriations. The Ad Valorem millage rate levied by the county for county government purposes is 6.8665.[43] The commission is responsible for providing appropriations for other countywide offices including the sheriff, property appraiser, tax collector and supervisor of elections. The county and circuit court systems are also partially supported by the county budget, including the state attorneys and public defenders. A portion of the county's budget is dedicated to providing municipal level services and regulations to unincorporated areas, such as zoning, business codes, and fire protection. Other services benefit both those in municipalities and in unincorporated Polk County, such as those that provide recreational and cultural opportunities.

Party registration

| Party | Number of registered voters | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | 149,743 | 35.7% | |

| Democratic | 147,652 | 35.2% | |

| Minor Party and non-affiliated | 121,590 | 29% | |

| Total | 418,985 | 100%[47] |

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 56.5% 194,586 | 42.1% 145,049 | 1.2% 4,391 |

| 2016 | 54.8% 157,430 | 40.9% 117,433 | 4.2% 12,106 |

| 2012 | 52.7% 131,577 | 45.9% 114,622 | 1.3% 3,243 |

| 2008 | 52.4% 128,878 | 46.3% 113,865 | 1.2% 2,961 |

| 2004 | 58.6% 123,559 | 40.8% 86,009 | 0.6% 1,262 |

| 2000 | 53.5% 90,310 | 44.6% 75,207 | 1.8% 3,112 |

| 1996 | 45.2% 67,962 | 44.4% 66,747 | 10.2% 15,464 |

| 1992 | 45.2% 65,963 | 35.2% 51,450 | 19.5% 28,487 |

| 1988 | 66.4% 77,104 | 32.9% 38,249 | 0.5% 687 |

| 1984 | 70.3% 84,246 | 29.6% 35,516 | 0.0% 22 |

| 1980 | 56.1% 59,651 | 40.7% 43,327 | 3.1% 3,337 |

| 1976 | 47.7% 44,238 | 51.0% 47,286 | 1.2% 1,182 |

| 1972 | 78.4% 60,748 | 21.2% 16,419 | 0.3% 293 |

| 1968 | 36.9% 27,839 | 21.1% 15,898 | 41.9% 31,540 |

| 1964 | 55.0% 35,906 | 44.9% 29,355 | |

| 1960 | 57.3% 31,618 | 42.6% 23,546 | |

| 1956 | 55.9% 23,682 | 44.0% 18,626 | |

| 1952 | 51.6% 20,874 | 48.3% 19,556 | |

| 1948 | 33.6% 7,692 | 52.5% 12,034 | 13.8% 3,166 |

| 1944 | 28.1% 5,150 | 71.8% 13,152 | |

| 1940 | 23.9% 5,564 | 76.0% 17,690 | |

| 1936 | 28.5% 4,164 | 71.4% 10,441 | |

| 1932 | 26.9% 3,490 | 73.0% 9,463 | |

| 1928 | 60.2% 7,460 | 36.9% 4,576 | 2.8% 350 |

| 1924 | 28.8% 1,530 | 57.9% 3,070 | 13.1% 696 |

| 1920 | 29.9% 1,782 | 65.8% 3,918 | 4.1% 249 |

| 1916 | 17.1% 578 | 76.1% 2,574 | 6.7% 229 |

| 1912 | 4.9% 106 | 71.4% 1,520 | 23.5% 502 |

| 1908 | 16.1% 290 | 69.6% 1,251 | 14.2% 256 |

| 1904 | 11.7% 125 | 81.4% 869 | 6.8% 73 |

| 1900 | 10.7% 133 | 79.6% 983 | 9.6% 119 |

| 1896 | 18.4% 279 | 76.2% 1,155 | 5.3% 81 |

| 1892 | 80.6% 869 | 19.3% 192 |

Education

Polk County Public Schools serves the county.

Universities and colleges

|

|

- Keiser University, Lakeland Campus (Private, Not-For-Profit)

- Southern Technical College, Auburndale Campus

Library Cooperative

The Polk County Library Cooperative was formed October 1, 1997 through an Interlocal Agreement between the 13 municipalities with public libraries and the Board of County Commissioners.[49] The Cooperative enables the city-owned and -operated public libraries to open their doors to all residents of the county, including those in the unincorporated area.[50]

Interlibrary Loan

Interlibrary Loan (ILL) offers library patrons the opportunity to request and receive books that are not owned by the Winter Haven Public Library. Through ILL, not only do patrons have access to the circulating book collections of all the library systems in Polk County but also all of the library systems in Florida, as well as universities and public library systems throughout the United States.[51]

Cooperative member libraries

|

Services

Polk County Historical & Genealogical Library

History

The Polk County Historical & Genealogical Library was established in 1937. It opened to the public in January 1940. The library was first located in the office of the County Attorney and its holdings were all housed in a metal bookcase. Since then the library has been housed in several different locations within the old Polk County Courthouse. In 1968 the library hired its first full-time employee. By 1974 the library added a second employee and was moved to a new location on Hendry Street. In 1987 the library relocated back to the 1908 Courthouse.

It was renovated during a ten-year process that included expansion to take over and adapt all three floors of the eastern wing of the Courthouse. As of 2013, the library is located in the east wing of the historical courthouse in Bartow. It is governed by the Polk County Board of County Commissioners (BoCC) and administered by the Neighborhood Services Department and the Leisure of Services Division. The library holds one of the largest genealogical and historical collections in the Southeast United States.[52]

Collections and Services

The Polk County Historical & Genealogical Library holds more than 40,000 items in its collection. The collection includes books, microfilm, and periodicals that include information about the history and genealogy of the entire eastern United States. The selection of materials related to the history of Polk County contains local newspapers dated back to 1881, aerial photography to 1938, city directories to 1925 and property tax rolls to 1882. Four full-time staff members are available for assistance at the library. The library also offers local obituary searches and basic looks-ups via email.[53]

Media

Polk is part of the Tampa Bay media market.[55]

Newspapers

- The Polk County Democrat 1931–present

- The Lakeland Ledger 1924–present; owned by New Media Investment Group

- The Winter Haven News Chief 1911–present

- The Business Observer 1997–present

Radio

| Callsign | City | Format |

|---|---|---|

| WLLD | Lakeland | Rhythmic contemporary |

| WLKF | News Talk Information | |

| WPCV | Country music | |

| WSEU | Contemporary Christian music, sports | |

| WWBF | Bartow | Classic hits music and Bartow High School sports |

| WLVF | Haines City | Southern gospel music |

Television

- WMOR-TV (licensed to Lakeland, with studios in Tampa)

Transportation

Airports

- Lakeland Linder International Airport In 2017 Linder welcomed its first international flight, and in 2018 the name was changed to reflect the airport's international status.[56]

- Bartow Municipal Airport

- Lake Wales Municipal Airport

- Jack Browns Seaplane Base

- Winter Haven's Gilbert Airport

- South Lakeland Airport

- Chalet Suzanne Air Strip

- River Ranch resort Airport

Highways

- Limited Access Highways

Interstate 4 – This interstate highway cuts across the northern part of the county, entering from Tampa and Plant City in the west, bypassing Lakeland, Auburndale, and Haines City, and heading northeast toward the greater Orlando area.

Interstate 4 – This interstate highway cuts across the northern part of the county, entering from Tampa and Plant City in the west, bypassing Lakeland, Auburndale, and Haines City, and heading northeast toward the greater Orlando area. Polk Parkway – With endpoints at I-4, this toll road traverses primarily around Lakeland, intersecting with several major routes in southern Lakeland and additionally providing access to Winter Haven and Legoland via SR 540, and Auburndale via US 92. It exists as SR 570.

Polk Parkway – With endpoints at I-4, this toll road traverses primarily around Lakeland, intersecting with several major routes in southern Lakeland and additionally providing access to Winter Haven and Legoland via SR 540, and Auburndale via US 92. It exists as SR 570.- Central Polk Parkway (Under Development)

- Heartland Parkway (proposed)

- U.S. Highways

US 17 – This U.S. highway enters Polk County from the southwest, bypassing Fort Meade on its way to Bartow, and eventually through Eagle Lake into Winter Haven. North of Winter Haven, in Lake Alfred, it joins with US 92 to form a concurrency that continues north and east through Haines City and Davenport toward Kissimmee and Orlando.

US 17 – This U.S. highway enters Polk County from the southwest, bypassing Fort Meade on its way to Bartow, and eventually through Eagle Lake into Winter Haven. North of Winter Haven, in Lake Alfred, it joins with US 92 to form a concurrency that continues north and east through Haines City and Davenport toward Kissimmee and Orlando. US 27 – This primary thoroughfare in eastern Polk County bypasses several cities, including Frostproof, Lake Wales, Dundee, Lake Hamilton, Haines City, and Davenport. Its interchange with I-4 is a gateway to the Orlando area.

US 27 – This primary thoroughfare in eastern Polk County bypasses several cities, including Frostproof, Lake Wales, Dundee, Lake Hamilton, Haines City, and Davenport. Its interchange with I-4 is a gateway to the Orlando area. US 92 – This route essentially parallels I-4 to the south over its journey through Polk County. From Plant City to the west, it enters Polk County and crosses Lakeland, emerging and continuing on through Auburndale. It joins US 17 in Lake Alfred.

US 92 – This route essentially parallels I-4 to the south over its journey through Polk County. From Plant City to the west, it enters Polk County and crosses Lakeland, emerging and continuing on through Auburndale. It joins US 17 in Lake Alfred. US 98 – This route crosses northwest to southeast across Polk County. Entering from Pasco County, it cuts through Lakeland and leads to Bartow. In Bartow, it begins a concurrency with US 17 through Fort Meade, where it jogs over to meet US 27 in Frostproof. US 98 is concurrent with US 27 as it exits Polk County to the southeast.

US 98 – This route crosses northwest to southeast across Polk County. Entering from Pasco County, it cuts through Lakeland and leads to Bartow. In Bartow, it begins a concurrency with US 17 through Fort Meade, where it jogs over to meet US 27 in Frostproof. US 98 is concurrent with US 27 as it exits Polk County to the southeast. US 192 – This highway has its western terminus at US 27 along the border of Polk and Lake Counties. It runs eastward from this junction to provide access to Disney World, the Orlando area, and the Space Coast.

US 192 – This highway has its western terminus at US 27 along the border of Polk and Lake Counties. It runs eastward from this junction to provide access to Disney World, the Orlando area, and the Space Coast.

- Major State Roads

State Road 17 – This scenic highway winds parallel to the east of US 27, running through the downtown areas of Lake Wales, Dundee, Lake Hamilton, and Haines City.

State Road 17 – This scenic highway winds parallel to the east of US 27, running through the downtown areas of Lake Wales, Dundee, Lake Hamilton, and Haines City. State Road 33 – It stems northward from Lakeland and leads to Polk City, and continues northward through the Green Swamp.

State Road 33 – It stems northward from Lakeland and leads to Polk City, and continues northward through the Green Swamp. State Road 37 – Also called South Florida Avenue, this road connects Mulberry to southern Lakeland.

State Road 37 – Also called South Florida Avenue, this road connects Mulberry to southern Lakeland. State Road 60 – The major route of southern Polk County and the county's largest state road, it connects Mulberry and Bartow with Lake Wales on its route from coast to coast in Florida.

State Road 60 – The major route of southern Polk County and the county's largest state road, it connects Mulberry and Bartow with Lake Wales on its route from coast to coast in Florida. State Road 540 – This road leads from Highland City in the Lakeland area to Winter Haven as Winter-Lake Road, then jogging over at US 17 and providing access to Legoland and US 27 as Cypress Gardens Boulevard.

State Road 540 – This road leads from Highland City in the Lakeland area to Winter Haven as Winter-Lake Road, then jogging over at US 17 and providing access to Legoland and US 27 as Cypress Gardens Boulevard. State Road 542 – This road travels through central Polk County, connecting downtown Winter Haven to US 27 and Dundee.

State Road 542 – This road travels through central Polk County, connecting downtown Winter Haven to US 27 and Dundee. State Road 544 – This road leads first from Auburndale to Winter Haven as Havendale Boulevard, and continues north and east as a scenic route to southern Haines City.

State Road 544 – This road leads first from Auburndale to Winter Haven as Havendale Boulevard, and continues north and east as a scenic route to southern Haines City. State Road 559 – This route straddles Lake Ariana in Auburndale and connects this city with Polk City, also providing access to I-4.

State Road 559 – This route straddles Lake Ariana in Auburndale and connects this city with Polk City, also providing access to I-4.

Intercity rail

Polk County has two Amtrak train stations, in Winter Haven and Lakeland. The Lakeland station is served by Amtrak's Silver Star while the Winter Haven station is served by both Amtrak's Silver Star and Silver Meteor.

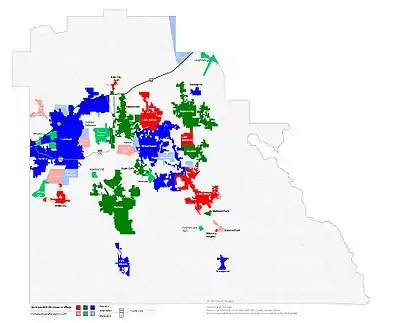

Communities

According to the 2010 Census, just under 38% of the population of the county lives in one of Polk's seventeen incorporated municipalities.[57] The largest city, Lakeland, has over 97,000 residents and is located in the western edge of the county. The other core city of the metropolitan area, Winter Haven, is located in the eastern part of the county and has 34,000 residents. The county seat, Bartow, is located southeast of Lakeland and southwest of Winter Haven and has over 17,000 residents. The cities of Bartow, Lakeland, and Winter Haven form a roughly equilateral triangle pointed downward with Bartow being the south point, Lakeland the west point, and Winter Haven the east point.[58][59]

The other major cities in the county with a population over 10,000 include Haines City, Auburndale, and Lake Wales. Haines City is in the northeast part of the county and has over 20,000 residents. Auburndale is located northwest of Winter Haven and Lake Wales is around 16 miles east of Bartow.

Cities

Village

Census-designated places

References

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- "OMB Bulletin No. 13-01: Revised Delineations of Metropolitan Statistical Areas, Micropolitan Statistical Areas, and Combined Statistical Areas, and Guidance on Uses of the Delineations of These Areas" (PDF). United States Office of Management and Budget. February 28, 2013. Retrieved March 20, 2013.

- "Table 1. Annual Estimates of the Population of Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2012". 2012 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. March 2013. Archived from the original (CSV) on April 1, 2013. Retrieved March 20, 2013.

- "Table 2. Annual Estimates of the Population of Combined Statistical Areas: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2012". 2012 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. March 2013. Archived from the original (CSV) on May 17, 2013. Retrieved March 20, 2013.

- "Centers of Population by State: 2010". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- "Ancient Native". HOTOA. Archived from the original on 2010-10-17. Retrieved 2010-09-09.

- "Polk County History". Polk Counjty Historical Association. Archived from the original on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2010-09-11.

- Weibel, B. "Trail of Florida's Ancient Heritage". active.com. Archived from the original on 2010-07-13. Retrieved 2010-09-09.

- Publications of the Florida Historical Society. Florida Historical Society. 1908. p. 33.

- Kimberly C. Moore, "Confederate vets, former slaves form Lakeland’s history", The Ledger, May 9, 2018; accessed June 27, 2018.

- Kimberly C. Moore, "Lynchings, Klan activity part of Polk’s history", The Ledger, May 7, 2018.

- "Woman's Impatience Revealed as Cause of Porter's Death". New York Negro World. May 29, 1920.

The woman sent a telegram to the next station stating that Scott had insulted her. When the train stopped, Scott was removed by a deputy sheriff. From there the story followed the usual lynching pattern. A mob “over-powered” the sheriff and killed the Negro. The coroner’s jury returned the usual verdict, “Death at the hands of parties unknown.”

- "Polk's Profile". Polk County Board of County Commissioners. Archived from the original on 2011-10-11. Retrieved 2011-10-27.

- "Airport History". Bartow Municipal Airport. Archived from the original on 2010-12-04. Retrieved 2010-09-12.

- "Unemployment Rate Polk County, FL". The Ledger. Archived from the original on 2013-03-10. Retrieved 2010-10-08.

- Bossak, Brian H. (April 2005). ""X" Marks the Spot: Florida, the 2004 Hurricane Bull's-Eye" (PDF). Sound Waves. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- Ledger, Gary White the. "The Ledger". www.theledger.com.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- Fraisse, Clyde. "USDA Plant Hardiness Information" (PDF). Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- Walter, Shoshana (January 9, 2010). "Snow, Sleet Pelt Frigid Polk". The Ledger. Lakeland, Florida. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- Collins, Jennifer; Paxton, Charles; Wahl, Thomas; Emrich, Christopher (November 2017). "Climate and Weather Extremes" (PDF). In Chassignet, Eric; Jones, James; Misra, Vasubandhu; Obeysekera, Jayantha (eds.). Florida's Climate: Changes, Variations, & Impacts. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. doi:10.17125/fci2017. ISBN 9781979091046. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- Maready, Jeremy (January 8, 2009). "One Year After Tragic I-4 Pileup, Questions Remain". The Ledger. Lakeland, Florida. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- Guinn, Christopher (July 15, 2017). "Climate researchers: As temperatures rise, Polk would be at heightened risk". The Ledger. Lakeland, Florida. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- Team, National Weather Service Corporate Image Web. "National Weather Service Climate". w2.weather.gov.

- "Historical Hurricane Tracks". NOAA Historical Hurricane Tracks Tool. NOAA. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- Chambliss, John; Rousso, Rick (August 13, 2004). "Charley Whips Through Polk". The Ledger. Lakeland, Florida. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

Over land, Charley lost some punch but still pummeled Lake Wales with gusts up to 101 mph and sustained winds of 95 mph for about 45 minutes, according to the Lake Wales Fire Department.

- Goldsmith, Barry (2004). "Hurricane Charley Preliminary Storm Survey I" (PDF). National Weather Service Tampa Bay Area Weather Forecast Office. pp. 3–4. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- Linhares, Mark (2004). "Hurricane Charley Preliminary Storm Survey II" (PDF). National Weather Service Tampa Bay Area Weather Forecast Office. pp. 1, 3. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- Pasch, Richard; Brown, Daniel; Blake, Erik (18 October 2004). "Tropical Cyclone Report - Hurricane Charley - 9-14 August 2004" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. p. 8. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- "Polk County: SELECTED SOCIAL CHARACTERISTICS IN THE UNITED STATES 2006–2010 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 23, 2015.

- "Polk County Demographic Characteristics". ocala.com. Archived from the original on July 19, 2018. Retrieved October 23, 2015.

- "Polk County: Age Groups and Sex: 2010–2010 Census Summary File 1". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 23, 2015.

- "Polk County, Florida: SELECTED ECONOMIC CHARACTERISTICS – 2006–2010 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 18, 2015.

- "Demographics of Polk County, FL". MuniNetGuide.com. Archived from the original on May 31, 2010. Retrieved October 23, 2015.

- Polk County Demographic Profile (Central Florida Development Council) Archived 2007-10-08 at the Wayback Machine – retrieved June 1, 2007

- "Modern Language Association Data Center Results of Polk County, Florida". Modern Language Association. Retrieved October 23, 2015.

- "Polk County Profile". Enterprise Florida. Retrieved 2011-10-27.

- "Top Employers ‹ Central Florida Development Council".

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-02-21. Retrieved 2013-11-18.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Board of County Commissioners". Polk County Website. Archived from the original on 2011-09-22. Retrieved 2011-09-27.

- "Active Voter Statistics". Archived from the original on 7 November 2018. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org.

- Schmidt, Carol. "Polk County Library Cooperative Coordinator Now Has Full-Time Job". The Ledger.

- "About Us - Polk County Library Cooperative". www.mypclc.org.

- "Library Services". whpl.mywinterhaven.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-10. Retrieved 2016-03-09.

- "About Us". Polk County Library Cooperative. Archived from the original on 2013-10-27. Retrieved 2013-08-09.

- "Overview". Polk County Library Cooperative. Archived from the original on 2012-08-26. Retrieved 2013-08-09.

- "Historical and Genealogical Library". Polk County Board of County Commissioners. Retrieved 2013-08-09.

- "Tampa Bay metro market hits milestone". www.bizjournals.com. July 18, 2007. Retrieved 2020-07-24.

- Moore, Kimberly C (12 July 2018). "Airport director on a mission to bring airline service to Lakeland Linder International Airport". Lakeland Ledger. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- "Census: Polk's Population Larger, More Diverse". The Ledger. Retrieved 2011-09-26.

- "Publication 04-39-087" (PDF). University of Florida. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-16. Retrieved 2010-10-17.

- "Map of Bartow, Lakeland, Winter Haven showing 'triangle'". Retrieved 2010-10-17.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Polk County, Florida. |

Government links/Constitutional offices

Special districts

Judicial branch

History

Miscellaneous

- Polk Partners, founded by the Lakeland Area Chamber of Commerce, Greater Winter Haven Chamber of Commerce, Central Florida Development Council, and The Ledger.

- Polk County Democrat local newspaper for Polk County, Florida fully and openly available in the Florida Digital Newspaper Library

- Polk County Guide online guide to attractions & events in Polk County, Florida