Tarboro, North Carolina

Tarboro is a town located in Edgecombe County, North Carolina, United States. It is part of the Rocky Mount Metropolitan Statistical Area. As of the 2010 census, the town had a population of 11,415.[5] It is the county seat of Edgecombe County.[6] The town is on the opposite bank of the Tar River from Princeville. It is also part of the Rocky Mount-Wilson-Roanoke Rapids CSA.[7] Tarboro is located near the western edge of North Carolina's coastal plain. It has many historical churches, some dating from the early 19th century.

Tarboro, North Carolina | |

|---|---|

| Town of Tarboro | |

Main Street, downtown | |

Seal | |

| Nickname(s): T-Town | |

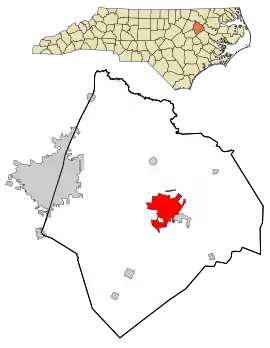

Location in Edgecombe County and the state of North Carolina. | |

| Coordinates: 35°54′10″N 77°32′45″W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Edgecombe |

| Founded | 1760 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–Manager |

| • Mayor | Joe W. Pitt |

| Area | |

| • Total | 11.60 sq mi (30.03 km2) |

| • Land | 11.56 sq mi (29.94 km2) |

| • Water | 0.04 sq mi (0.10 km2) |

| Elevation | 43 ft (13 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 11,415 |

| • Estimate (2019)[2] | 10,715 |

| • Density | 926.90/sq mi (357.89/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 27886 |

| Area code(s) | 252 |

| FIPS code | 37-66700[3] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1022886[4] |

| Website | www |

Tarboro was chartered by British colonists in 1760. Located in a bend of the Tar River, it was an important river port, the head of navigation on the Tar just east of the fall line of the Piedmont. As early as the 1730s, a small European-American community developed around this natural asset. Its warehouse, customs office and other commercial concerns, together with a score of "plain and cheap" houses, made a bustling village.

History

Created in 1760, Tarboro is the ninth-oldest incorporated town in North Carolina. Situated on the Tar River at the fall line in the Piedmont, the town served the area as an important colonial river port. It was a thriving trade center until the Civil War.

Scholars believe that the area around Tarboro was settled by 1733, but Edward Moseley's map of that year indicates only Tuscarora Native Americans, an Iroquoian-language speaking group. By 1750, the area was widely known as "Tawboro", a name attributed to Taw, the Tuscaroran word for "river of health".

"Tarrburg", as the town was called on maps of 1770–75, was chartered November 30, 1760, as "Tarborough" by the General Assembly. In September of the same year, Joseph and Ester Howell deeded 150 acres (610,000 m2) of their property to the Reverend James Moir, Lawrence Toole (a merchant), Captains Aquilla Sugg and Elisha Battle, and Benjamin Hart, Esquire, for five shillings and one peppercorn. As commissioners, these men laid out a town with lots not exceeding 0.5 acres (2,000 m2) and streets not wider than 80 feet (24 m), with 12 lots and a 50-acre (200,000 m2) "common" set aside for public use. Lots were to be sold for two pounds, with the proceeds to be turned over to the Howells; however, full payment was not received for all of the 109 lots sold, and some were not sold for the 40 shillings price.

After Halifax County was separated from Edgecombe County in 1758–59, the original county seat of Enfield was within Halifax.

Tarboro officially was designated as the county seat of Edgecombe in 1764. For four years the county government had met in Redman's Field. The North Carolina State Legislature met here once in 1787 and again in 1987. President George Washington is known to have slept in Tarboro during a visit on his 1791 Southern tour. He is noted to have said of the town that it was "as good a salute as could be given with one piece of artillery."[8]

According to the book, Edgecombe County: Twelve North Carolina Counties in 1810–11, by Dr Jeremiah Battle, the following is an 1810 account of the town:

"Tarboro, the only town in the county, is handsomely situated on the south-west bank of Tar River, just above the mouth of Hendrick's Creek, in lat. 35 deg. 45 min. It is forty-eight miles west by north from Washington, thirty-six south of Halifax, eighty-three northwest of Newbern, and sixty-eight east of Raleigh. It was laid off into lots in the year 1760. The streets are seventy-two feet wide, and cross each other at right angles, leaving squares of 2 acres (8,100 m2) each. These squares being divided into lots of 0.5 acres (2,000 m2), makes every lot front or face two streets.

"There are about fifty private houses in it; and generally from fifteen to twenty stores, a church, a jail, two warehouses, and a large Court House, which in the year 1785 was used for the sitting of the State Legislature. There are several good springs adjacent to the town, but for culinary purposes almost every person or family has a well; and some of these wells afford good water the greater part of the year. This place affords good encouragement to all industrious persons, particularly merchants of almost every description. Sixty or seventy merchants have had full employment here at one time. But such of them as have emigrated to this place have too soon found themselves in prosperous situations, and have betaken themselves to idleness and dissipation."

Due to the development of cotton plantations in the uplands, which were worked by slave labor in the antebellum years, by the 1870s Halifax and Edgecombe counties were among several in northeast North Carolina with majority-black populations. Before being disfranchised by the Democrats' passage in 1899 of a new state constitutions, black citizens elected four African Americans to the US Congress from North Carolina's 2nd congressional district in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. They also elected many blacks to local offices. Congressman George Henry White, a successful attorney, lived in Tarboro. After passage of the disfranchising constitution, he left the state, stating it was impossible for a black to be a man there. He became a successful banker in Washington, DC, and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

The federal Voting Rights Act of 1965 provided for oversight and enforcement of the constitutional rights of African Americans to vote. They have since been able to participate again in political life in North Carolina.

Hurricane Floyd

Hurricane Floyd was a very powerful Cape Verde-type hurricane that struck the east coast of the United States in 1999. It was the sixth named storm, fourth hurricane, and third major hurricane in the 1999 Atlantic hurricane season. With its approach, officials ordered the third largest evacuation in US history (behind Hurricane Gustav and Hurricane Rita, respectively), and 2.6 million coastal residents of five states were ordered from their homes. The hurricane formed off the coast of Africa and lasted from September 7 to September 19, peaking in strength as a very strong Category 4 hurricane—just 2 mph short of the highest possible rating on the Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Scale.

Flooding in Tarboro occurred mostly in areas around the Tar River, which exceeded 500-year flood levels along its lower stretches; it crested 24 ft (7.3 m) above flood stage. The Tar River surrounds about half of Tarboro as both the North end and Southern ends of the city have developed along it. Flooding began upstream in Rocky Mount, where up to 30% of the city was underwater for several days. In Tarboro, much of the downtown became flooded by several feet of water.[9] Nearby, the town of Princeville was largely destroyed when the waters of the Tar poured over the town's levee, covering the town with more than 20 ft (6.1 m) of floodwater for ten days.[10] Part of the Tarboro and Princeville city limits are defined by the Tar River.

Tarboro Historic District

Recognized by the National Park Service in 1977, the 45-block Tarboro Historic District has more than 300 contributing structures, from residences to historic churches to original 19th-century storefronts along Tarboro's Main Street. The gateway to the Tarboro Historic District is the Tarboro Town Common, a 15-acre (61,000 m2) park that has a canopy of tall oaks. War memorials are installed here. The Town Common originally surrounded the town and is the second-oldest legislated town common in the country. Initially the location for common grazing of livestock, community gatherings and military drills, the Town Common is the only remaining original common on the East Coast outside of Boston.

%252C_Tarboro%252C_Edgecombe_County%252C_NC_HABS_NC%252C33-TARB%252C2-3.tif.jpg.webp)

Within the historic district is the Blount-Bridgers House, an 1808 Federal-style mansion that is operated as a museum: it holds several important document collections and works by Hobson Pittman, a nationally recognized artist and Tarboro native. Opened to the public in 1982, the Blount-Bridgers House serves as the town's art and civic center. A self-guided Historic District National Recreation Trail, beginning at the Blount-Bridgers House, leads visitors through the scenic older neighborhoods of the town. The district includes five 18th-century homes, with the oldest being the Archibald White house (ca. 1785) located on the corner of Church and Trade streets. The district has more than two dozen antebellum homes built from 1800 to 1860. The largest section is late 19th-and early 20th-century and includes Victorian, Second Empire, Neo-classical revival, and Arts and Crafts-style homes. The town's walkable downtown is recognized by the National Trust for Historic Preservation's Main Street Program.

Also within the historic district, at the cross of North Church Street and Albemarle Avenue, is the Tarboro-Edgecombe Farmers' Market. The market operates on Tuesdays and Fridays from 7 am to 10 am, and Saturdays from 8 am to 11 am. A variety of events, including the Tarboro Commons Festival and the Blueberry Day, are celebrated in downtown.

Additional buildings are listed on the National Register of Historic Places: The Barracks, Batts House and Outbuildings, Calvary Episcopal Church and Churchyard, Coats House, Coolmore Plantation, Cotton Press, Eastern Star Baptist Church, Edgecombe Agricultural Works, Howell Homeplace, Lone Pine, Oakland Plantation, Piney Prospect, Quigless Clinic, Railroad Depot Complex, Redmond-Shackelford House, St. Paul Baptist Church, and Walston-Bulluck House.[11]

Geography

Tarboro is located at 35°54'10" North, 77°32'45" West (35.902850, −77.545959).[12]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 11.2 square miles (28.9 km2), of which 11.1 square miles (28.8 km2) is land and 0.04 square miles (0.1 km2), or 0.33%, is water.[5]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1810 | 523 | — | |

| 1850 | 709 | — | |

| 1860 | 1,048 | 47.8% | |

| 1870 | 1,340 | 27.9% | |

| 1880 | 1,600 | 19.4% | |

| 1890 | 1,924 | 20.3% | |

| 1900 | 2,499 | 29.9% | |

| 1910 | 4,129 | 65.2% | |

| 1920 | 4,568 | 10.6% | |

| 1930 | 6,379 | 39.6% | |

| 1940 | 7,148 | 12.1% | |

| 1950 | 8,120 | 13.6% | |

| 1960 | 8,411 | 3.6% | |

| 1970 | 9,425 | 12.1% | |

| 1980 | 8,741 | −7.3% | |

| 1990 | 11,037 | 26.3% | |

| 2000 | 11,138 | 0.9% | |

| 2010 | 11,415 | 2.5% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 10,715 | [2] | −6.1% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[13] | |||

As of the census of 2010, there were 11,415 people, 4,565 households, and 2,958 families residing in the town. The population density was 1,025.3 people per square mile (395.9/km2). There were 4,993 housing units at an average density of 448.5 per square mile (173.2/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 47.2% White, 48.4% African American, 0.1% Native American, 0.5% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 2.9% some other race, and 0.8% from two or more races. 4.9% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.[14]

There were 4,565 households, out of which 30.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 38.5% were headed by married couples living together, 22.1% had a female householder with no husband present, and 35.2% were non-families. 31.5% of all households were made up of individuals, and 15.1% were someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.35, and the average family size was 2.94.[14]

In the town, the population was spread out, with 22.8% under the age of 18, 8.1% from 18 to 24, 22.1% from 25 to 44, 27.9% from 45 to 64, and 19.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 42.3 years. For every 100 females, there were 84.1 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 79.3 males.[14]

For the period 2010–14, the estimated median annual income for a household in the town was $34,267, and the median income for a family was $46,884. Male full-time workers had a median income of $32,776, versus $35,013 for females. The per capita income for the town was $20,085. 16.0% of the population and 12.0% of families were below the poverty line. Out of the total population, 28.9% of those under the age of 18 and 11.7% of those 65 and older were living below the poverty line.[15]

Economy

Chinese tiremaker Triangle Group will be building two manufacturing facilities at a 1,449-acre site in Edgecombe County at Kingsboro Business Park, located between Rocky Mount and Tarboro. Phase 1 of the project is set to open in 2020 and phase 2 in 2022. At $580 million, it will be the largest ever manufacturing investment in rural North Carolina with the creation of 800 jobs and an estimated contribution of more than $2.4 billion to the state's economy.[16] Corning has also constructed a new $86 million distribution center that will bring 111 new jobs, they will be operational in the first quarter 2020.[17][18]

Largest employers

Below is a list of some of the largest employers in Tarboro as of 2019.[19][20]

| # | Employer | No. of employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Edgecombe County Public Schools | 1,100 |

| 2 | Sara Lee Frozen Bakery | 950 |

| 3 | Edgecombe County | 500-999 |

| 4 | Johnson Controls | 250-499 |

| 5 | Vidant Edgecombe Hospital | 500-999 |

| 6 | Keihin Carolina System Technology | 250-499 |

| 7 | Barnhill Contracting | 100-249 |

| 8 | LS Cable | 100-249 |

| 9 | Town of Tarboro | 100-249 |

Education

Edgecombe County Public Schools' headquarters are located in Tarboro, and the schools serve all cities and towns of the county. ECPS operates a total of 15 public schools: 6 elementary schools, 4 middle schools, and 5 high schools. Tarboro is home to seven of the public schools: Stocks Elementary, Princeville Elementary, Pattillo Middle School, Martin Millennium Academy, Edgecombe Early College High School, North Edgecombe High School and Tarboro High School.[21] There is one public charter school in Tarboro, North East Carolina Prep School.[22]

Higher education is provided by Edgecombe Community College. ECC offers more than 130 academic degrees, diplomas, and certificates. Edgecombe also operates a separate campus in nearby Rocky Mount.[23]

Government

The town of Tarboro has a council-manager form of government. The town is divided into eight wards with a total of eight council members that serve members of the town's council are elected from the town's eight wards for four-year staggered terms. The mayor serves a four-year term.[24] As of 2019, the town manager is Troy R. Lewis.

Council members

- Joe W. Pitt (Mayor)

- Othar Woodard (Ward 1)

- Leo Taylor (Ward 2)

- Steve Burnette (Ward 3)

- C.B. Brown (Ward 4)

- John Jenkins (Ward 5)

- Deborah Jordan (Ward 6)

- Sabrina Bynum (Ward 7)

- Tate Mayo (Ward 8)

Infrastructure

Transportation

Interstate 95 and U.S. 64 were constructed near Tarboro, allowing for access to and from the East Coast's major markets, many of which are within one day's drive. The city is 72 miles (116 km) east of Raleigh, the state capital; 25 miles (40 km) northwest of Greenville, a primary eastern North Carolina hub; 16 miles (26 km) east of Rocky Mount; and 120 miles (190 km) west of the Outer Banks. Tarboro is convenient to area and regional airports, freight and passenger train service, interstate and intrastate highway systems, and the deepwater ports of Morehead City and Wilmington, North Carolina.

Major highways

US 64: Four-laned from Tarboro west to Raleigh, and four-laned from Tarboro east to North Carolina's Outer Banks.

US 64: Four-laned from Tarboro west to Raleigh, and four-laned from Tarboro east to North Carolina's Outer Banks. US 258: A major north-south link between the Norfolk area and Jacksonville, North Carolina.

US 258: A major north-south link between the Norfolk area and Jacksonville, North Carolina. I-95: Located 22 miles (35 km) west of Tarboro (accessed via four-laned U.S. 64), this major interstate provides access to Washington, D.C., New York City, the Northeast, and Florida.

I-95: Located 22 miles (35 km) west of Tarboro (accessed via four-laned U.S. 64), this major interstate provides access to Washington, D.C., New York City, the Northeast, and Florida.

Airports

Tarboro-Edgecombe Airport: This facility, located 3 miles (5 km) north of downtown, has a 4,500-foot (1,400 m) paved and lighted runway with a 1,000-foot (300 m) approach apron from both ends, accommodating a wide variety of small general aviation aircraft.

Pitt–Greenville Airport: Located 25 miles (40 km) south of Tarboro, this airport has a 6,000-foot (1,800 m) lighted precision approach runway, a 5,000-foot (1,500 m) lighted non-precision crosswind runway and a 2,700-foot (820 m) unlighted visual approach runway. PGV provides commuter service to Charlotte Douglas International Airport through US Airways Express with 11 daily flights. Jet service is available. All aircraft services are available, including charters.

Rocky Mount-Wilson Airport: Located 25 miles (40 km) west of Tarboro, this airport has one runway which is lighted and extends a length of 7,100 feet (2,200 m).

Raleigh–Durham International Airport: More commonly known as RDU, this major international airport serves the U.S. and abroad. Located 87 miles (140 km) west of Tarboro, RDU hosts numerous major carriers with daily departures. Additionally, numerous commuter carriers connect RDU to the northeast and other southern cities.

Rail

Tarboro has access to both freight and passenger rail service. Amtrak provides two north and two southbound trains per day at its Rocky Mount station, located 17 miles (27 km) west of Tarboro. Service is to Washington, D.C., New York City, Miami and Philadelphia. Freight service is provided by CSX. Trains travel to destinations in eastern North Carolina and also to points west and south of town.

Health care

Vidant Edgecombe Hospital is a full-service, 117-bed acute care facility where residents of Tarboro, Edgecombe County and surrounding communities receive a wide range of health services close to home. In 1998, Heritage joined University Health Systems of Eastern Carolina which is now Vidant Health. More than 20 specialties are represented by Vidant Edgecombe Hospital's medical staff. In addition to acute care, services include rehabilitation, oncology and outpatient clinics.[25]

Media

The Tarboro Weekly and Tar River Times serves as the main daily newspapers for the town of Tarboro and surrounding areas.[26][27] The Daily Southerner was the main daily newspaper for the town of Tarboro and Edgecombe County from 1826 until it ceased publication on May 30, 2014.

The Rocky Mount Telegram also serves the town of Tarboro and the entire Rocky Mount metropolitan area.[28]

Notable people

- Kelvin Bryant, retired NFL running back[29]

- Mike Caldwell, Major League Baseball player[30]

- Elijah Clarke, Revolutionary War hero and namesake of Clarke County, Georgia

- Shaun Draughn, running back for the San Francisco 49ers[31]

- L. H. Fountain, congressman[32]

- Todd Gurley, running back for the Atlanta Falcons[33]

- Brian Hargrove, television writer/producer[34]

- Montrezl Harrell, professional basketball player for the Los Angeles Lakers

- Janice Bryant Howroyd, first African American woman to build and own a billion dollar company[35]

- Ben Jones, politician, actor

- Joshua Lawrence (1778–1843), influential Baptist minister

- Derrick Lewis, professional basketball player[36]

- Tyquan Lewis, NFL defensive lineman

- Jim Phillips Sr., North Carolina state senators

- General Hugh Shelton, former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

- Hubert Simmons, Negro league baseball player for the Baltimore Elite Giants

- Joseph K. Spiers, U.S. Air Force general

- Rear Admiral Adolphus Staton, United States Navy

- Trent Tucker, former NBA player

- Harvie Ward, former professional golfer best known for his amateur career[37]

- Ed Weeks, set numerous records for growing large vegetables[38]

- Milton Moran Weston II, activist, clergyman, businessman[39]

- George Henry White, African-American attorney and last black US Congressman elected from North Carolina in the 19th century; lived in Tarboro when elected in 1898, and moved away at the end of his term in protest against the disenfranchisement of blacks by the state legislature

- Burgess Whitehead, MLB player

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Tarboro town, North Carolina". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2018 - United States -- Combined Statistical Area; and for Puerto Rico". American FactFinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved July 15, 2019.

- Henderson, Archibald (1923). Washington's Southern Tour, 1791. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 78.

- "Flooding in Tarboro and Princeville". Daniel Design Associates. Archived from the original on August 7, 2008. Retrieved October 4, 2008.

- "The History of Princeville". Town Of Princeville, North Carolina. Retrieved March 11, 2006.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Census Summary File 1 (DP-1): Tarboro town, North Carolina". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- "Selected Economic Characteristics: 2010–2014 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates (DP03): Tarboro town, North Carolina". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- Davis, Corey (December 20, 2017). "Tire plants to create 800 jobs". Rocky Mount Telegram. Retrieved May 18, 2018.

- Davis, Corey (July 15, 2018). "Corning prepares to construct new warehouse". Rocky Mount Telegram. Retrieved May 18, 2018.

- Walker, John (October 1, 2019). "Work continues at Kingsboro site". Rocky Mount Telegram. Retrieved November 12, 2019.

- "Major Employers in Rocky Mount MSA (Edgecombe & Nash) 2018" (PDF). econdev.org. Retrieved April 19, 2019.

- "Tarboro Data" (PDF). tarboronc. Retrieved November 13, 2019.

- "Edgecombe County Public Schools". ECPS. Retrieved November 14, 2019.

- "North East Carolina Preparatory School". necprepschool. Retrieved November 14, 2019.

- "Edgecombe Community College". edgecombe.edu. Retrieved November 14, 2019.

- "Welcome to Tarboro's Administrative Department!". tarboronc. Retrieved November 14, 2019.

- "VIDANT EDGECOMBE HOSPITAL". vidanthealth. Retrieved November 13, 2019.

- "Tarboro Weekly". rockymounttelegram. Retrieved November 13, 2019.

- "Tar River Times". tarrivertimes. Retrieved November 13, 2019.

- "Home - Rocky Mount Telegram". Rocky Mount Telegram. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- "Kelvin Bryant player stats". NFL. Retrieved November 15, 2019.

- "Mike Caldwell". baseball-reference. Retrieved November 15, 2019.

- Player Bio: Shaun Draughn, University of North Carolina, retrieved November 15, 2019.

- "Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, 1774-Present". bioguide.congress.gov/. Retrieved November 27, 2019.

- "Tarboro native Todd Gurley selected 10th in NFL draft by the Rams". WITN. Retrieved November 27, 2019.

- "Brian Hargrove". imdb.com. Retrieved November 27, 2019.

- "Entrepreneur Mom: Janice Bryant Howroyd". October 28, 2008. Retrieved November 15, 2019.

- "Maryland Basketball 1986–87". University of Maryland, College Park. 1986. pp. 20–21.

- Edward Harvie Ward, Jr. | Twin County Hall of Fame. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- Associated Press (25 July 1970). "118 Pound Melon". Daytona Beach Morning Journal. p. 6D. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- Martin, Douglas (May 22, 2002). "M. Moran Weston, 91, Priest and Banker of Harlem, Dies" – via NYTimes.com.