Alamance County, North Carolina

Alamance County /ˈæləmæns/ (![]() listen)[2] is a county in North Carolina. As of the 2010 census, the population was 151,131.[3] Its county seat is Graham.[4] Formed in 1849 from Orange County to the east, Alamance County has been the site of significant historical events, textile manufacturing, and agriculture.

listen)[2] is a county in North Carolina. As of the 2010 census, the population was 151,131.[3] Its county seat is Graham.[4] Formed in 1849 from Orange County to the east, Alamance County has been the site of significant historical events, textile manufacturing, and agriculture.

Alamance County | |

|---|---|

| |

Flag  Seal | |

| Motto(s): Pro Bono Publico (For the Public Good) | |

Location within the U.S. state of North Carolina | |

North Carolina's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 36°02′N 79°24′W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | January 29, 1849 |

| Named for | Native American word to describe the mud in Great Alamance Creek |

| Seat | Graham |

| Largest city | Burlington |

| Area | |

| • Total | 435 sq mi (1,130 km2) |

| • Land | 424 sq mi (1,100 km2) |

| • Water | 11 sq mi (30 km2) 2.5%% |

| Population | |

| • Estimate (2019) | 169,509[1] |

| • Density | 356/sq mi (137/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Congressional district | 13th |

| Website | www |

Alamance County comprises the Burlington Metropolitan Statistical Area, which is also included in the Greensboro-Winston-Salem-High Point Combined Statistical Area. The 2018 estimated population of the metropolitan area was 166,436.[3]

History

Before being formed as a county, the region had at least one known small Southeastern tribe of Native American in the 18th century, the Sissipahaw, who lived in the area bounded by modern Saxapahaw, the area known as the Hawfields, and the Haw River.[5][6] European settlers entered the region in the late 17th century chiefly following Native American trading paths, and set up their farms in what they called the "Haw Old Fields", fertile ground previously tilled by the Sissipahaw. The paths later became the basis of the railroad and interstate highway routes.[7]

Alamance County was named after Great Alamance Creek, site of the Battle of Alamance (May 16, 1771), a pre-Revolutionary War battle in which militia under the command of Governor William Tryon crushed the Regulator movement. Great Alamance Creek, and in turn Little Alamance Creek, according to legend, were named after a local Indian word to describe the blue mud found at the bottom of the creeks. Other legends say the name came from another local Indian word meaning "noisy river", or for the Alamanni region of Rhineland, Germany, where many of the early settlers came from.[8]

During the American Revolution, several small battles and skirmishes occurred in the area that became Alamance County, several of them during the lead-up to the Battle of Guilford Court House, including Pyle's Massacre, the Battle of Lindley's Mill,[9] and the Battle of Clapp's Mill.[10]

In the 1780s, the Occaneechi Indians returned to North Carolina from Virginia, this time settling in what is now Alamance County rather than their first location near Hillsborough.[11] In 2002, the modern Occaneechi tribe bought 25 acres (100,000 m2) of their ancestral land in Alamance County and began a Homeland Preservation Project that includes a village reconstructed as it would have been in 1701 and a 1930s farming village.[11]

During the early 19th century, the textile industry grew heavily in the area, so the need for better transportation grew. By the 1840s, several mills were set up along the Haw River and near Great Alamance Creek and other major tributaries of the Haw. Between 1832 and 1880, at least 14 major mills were powered by these rivers and streams. Mills were built by the Trollinger, Holt, Newlin, Swepson, and Rosenthal families, among others. One of them, built in 1832 by Ben Trollinger, is still in operation. It is owned by Copland Industries, sits in the unincorporated community of Carolina and is the oldest continuously operating mill in North Carolina.[12]

One notable textile produced in the area was the "Alamance plaids" or "Glencoe plaids" used in everything from clothing to tablecloths.[12] The Alamance Plaids manufactured by textile pioneer Edwin M. Holt were the first colored cotton goods produced on power looms in the South, and paved the way for the region's textile boom.[13] (Holt's home is now the Alamance County Historical Society.[14]) But by the late 20th century, most of the plants and mills had gone out of business, including the mills operated by Burlington Industries, a company based in Burlington.

By the 1840s, the textile industry was booming, and the railroad was being built through the area as a convenient link between Raleigh and Greensboro. The county was formed on January 29, 1849[15] from Orange County.

Civil War

In March 1861, Alamance County residents voted overwhelmingly against North Carolina's secession from the Union, 1,114 to 254. Two delegates were sent to the State Secession Convention, Thomas Ruffin and Giles Mebane, who both opposed secession, as did most of the delegates sent to the convention.[16] At the time of the convention, around 30% of Alamance County's population were slaves (total population around 12,000, including roughly 3,500 slaves and. 500 free blacks).

North Carolina was reluctant to join other Southern states in secession until the Battle of Fort Sumter in April 1861. When Lincoln called up troops, Governor John Ellis replied, "I can be no party to this wicked violation of the laws of the country and to this war upon the liberties of a free people. You can get no troops from North Carolina." After a special legislative session, North Carolina's legislature unanimously voted for secession on May 20, 1861.

No battles took place in Alamance County, but it sent its share of soldiers to the front lines. In July 1861, for the first time in American history, soldiers were sent in to combat by rail. The 6th North Carolina was loaded onto railroad cars at Company Shops and transferred to the battlefront at Manassas, Virginia (First Battle of Manassas).

Although the citizens of Alamance County were not directly affected throughout much of the war, in April 1865, they witnessed firsthand their sons and fathers marching through the county just days before the war ended with the surrender at Bennett Place near Durham. At Company Shops, General Joseph E. Johnston stopped to say farewell to his soldiers for the last time. By the end of the war, 236 people from Alamance County had been killed in the course of the war, more than any other war since the county's founding.[17]

Aftermath

Some of the Civil War's most significant effects were seen after it ended. Alamance County briefly became a center of national attention when in 1870 Wyatt Outlaw, an African-American town commissioner in Graham, was lynched by the "White Brotherhood", the Ku Klux Klan. He was president of the Alamance County Union League of America (a progressive reform branch of the Federal Government), helped to establish the Republican party in North Carolina, and advocated establishing a school for African Americans. His offense was that Governor William Holden had appointed him a justice of the peace, and he had accepted the appointment. Outlaw's body was found hanging 30 yards from the courthouse, with a note pinned to his chest reading, "Beware! You guilty parties – both white and black." Outlaw was the central figure in political cooperation between blacks and whites in the county.

Holden declared Caswell County in a state of insurrection (July 8) and sent troops to Caswell and Alamance Counties under the command of Union veteran George W. Kirk, beginning the so-called Kirk-Holden War. Kirk's troops ultimately arrested 82 men.

The Grand Jury of Alamance County indicted 63 klansmen for felonies and 18 for the murder of Wyatt Outlaw. Soon after the indictments were brought, Democrats in the legislature passed a bill to repeal the law under which the indictments had been secured. The 63 felony charges were dropped. The Democratic Party then used a national program of "Amnesty and Pardon" to proclaim amnesty for all who committed crimes on behalf of a secret society. This was extended to the klansmen of Alamance County. There would be no justice in the case of Wyatt Outlaw.

Holden's support for Reconstruction led to his impeachment and removal by the North Carolina Legislature in 1871.

Dairy industry

The county was once the state leader in dairy production. Several dairies including Melville Dairy in Burlington were headquartered in the county. With increasing real estate prices and a slump in milk prices, most dairy farms have been sold and many of them developed for real estate purposes.

World War II and the Cold War

During World War II, Fairchild Aircraft built airplanes at a plant on the eastern side of Burlington. Among the planes built there was the AT-21 gunner, used to train bomber pilots. Near the Fairchild plant was the Western Electric Burlington works. During the Cold War, the plant built radar equipment and guidance systems for missiles and many other electronics for the government, including the guidance system for the Titan missile. The plant closed in 1992 and sat abandoned until 2005, when it was purchased by a local businessman for manufacturing.

The USS Alamance, a Tolland-class attack cargo ship, was built during and served in and after World War II.

21st Century

Alamance County's population has grown significantly, with the city of Mebane tripling in size between 1990 and 2020. The county has seen significant business and industry growth, including the additions of the North Carolina Commerce Park and the North Carolina Industrial Center, as well as new retail opportunities near Interstate 85/40 on the eastern (Tanger Outlets) and western (University Commons and Alamance Crossing) sides of the county.[18]

Some growth has been attributed to illegal immigration, which has led to ongoing legal issues. In 2012, the Department of Justice found the Alamance County Sheriff's Office to use discriminatory policing,[19] however the case was dismissed by U.S. District Court Judge Thomas D. Schroeder, finding that the government failed to demonstrate that the ACSO had engaged in discriminatory policing. [20]

Beginning in 2014, the county has been home to a number of political demonstrations.[21] In October, 2020, during a demonstration prior to the 2020 United States Presidential Election, Alamance County sheriff’s deputies and Graham police used pepper spray against crowd members.[22] Law enforcement reported that pepper spray had been deployed to disperse the crowd following an assault on an officer who was trying to shut down a generator the march organizers had brought, in violation of a signed agreement.[23]

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 435 square miles (1,130 km2), of which 424 square miles (1,100 km2) are land and 11 square miles (28 km2) (2.5%) are covered by water.[24]

The county is in the Piedmont physiographical region. It has a general rolling terrain with the Cane Creek Mountains rising to over 970 ft (300 m)[25] in the south-central part of the county just north of Snow Camp. Bass Mountain, one of the prominent hills in the range, is home to a world-renowned bluegrass music festival every year. Also, isolated monadnocks are in the northern part of the county that rise to near or over 900 ft (270 m) above sea level.

The largest river that flows through Alamance County is the Haw, which feeds into Jordan Lake in Chatham County, eventually leading to the Cape Fear River. The county is also home to numerous creeks, streams, and ponds, including Great Alamance Creek, where a portion of the Battle of Alamance was fought. The three large municipal reservoirs are: Lake Cammack, Lake Mackintosh, and Graham-Mebane Lake (formerly Quaker Lake). The southwest end of the county is drained by North Rocky River Prong and Greenbrier Creek, two tributaries of the Rocky River in the Deep River system.

Adjacent counties

- Caswell County - north

- Orange County - east

- Chatham County - southeast and south

- Randolph County - southwest

- Guilford County - west

- Rockingham County - northwest

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1850 | 11,444 | — | |

| 1860 | 11,852 | 3.6% | |

| 1870 | 11,874 | 0.2% | |

| 1880 | 14,613 | 23.1% | |

| 1890 | 18,271 | 25.0% | |

| 1900 | 25,665 | 40.5% | |

| 1910 | 28,712 | 11.9% | |

| 1920 | 32,718 | 14.0% | |

| 1930 | 42,140 | 28.8% | |

| 1940 | 57,427 | 36.3% | |

| 1950 | 71,220 | 24.0% | |

| 1960 | 85,674 | 20.3% | |

| 1970 | 96,362 | 12.5% | |

| 1980 | 99,319 | 3.1% | |

| 1990 | 108,213 | 9.0% | |

| 2000 | 130,800 | 20.9% | |

| 2010 | 151,131 | 15.5% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 169,509 | [26] | 12.2% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[27] 1790-1960[28] 1900-1990[29] 1990-2000[30] 2010-2013[3] | |||

As of the census[31] of 2010, there were 151,131 people, 59,960 households, and 39,848 families residing in the county. The population density was 347.4 people per square mile (134.1/km2). There were 66,055 housing units at an average density of 151.9 per square mile (58.6/km2). The racial makeup of the county was 71.1% White, 18.8% Black or African American, 0.7% Native American, 1.2% Asian, 0.02% Pacific Islander, 6.1% from other races, and 2.1% from two or more races. 11% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 59,960 households, out of which 29.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 47.2% were married couples living together, 14.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 33.5% were non-families. 27.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 26.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.45 and the average family size was 2.98.

In the county, the population was spread out, with 26.7% under the age of 19, 7.2% from 20 to 24, 25.1% from 25 to 44, 26.3% from 45 to 64, and 14.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 38.7 years. For every 100 females there were 92.50 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 89.00 males.

The median income for a household in the county was $44,430, and the median income for a family was $54,605. Males had a median income of $31,906 versus $23,367 for females. The per capita income for the county was $23,477. About 13.7% of families and 16.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 25% of those under age 18 and 8.7% of those age 65 or over.

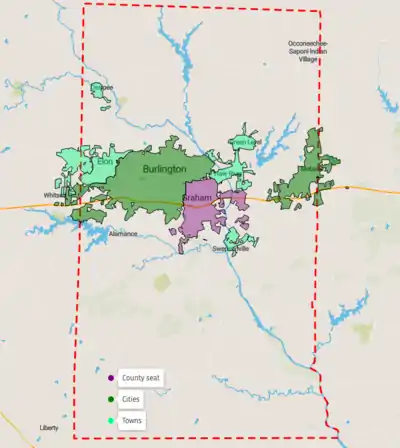

Communities

Cities

- Burlington

- Graham (county seat)

- Mebane (portion)

Towns

- Elon

- Gibsonville (portion)

- Green Level

- Haw River

- Ossipee

- Swepsonville

Village

Townships

The county is divided into thirteen townships, which are both numbered and named.

- 1 (Patterson)

- 2 (Coble)

- 3 (Boone Station)

- 4 (Morton)

- 5 (Faucette)

- 6 (Graham)

- 7 (Albright)

- 8 (Newlin)

- 9 (Thompson)

- 10 (Melville)

- 11 (Pleasant Grove)

- 12 (Burlington)

- 13 (Haw River)

Census-designated places

Unincorporated communities

Over 54,000 people do not live in an incorporated community in Alamance County.

Ghost towns

According to a 1975 study of the history of post offices in North Carolina by Treasure Index, Alamance County has 27 ghost towns that existed in the 18th and 19th centuries. Additionally, five other post offices no longer exist. These towns and their post offices were either abandoned as organized settlements or absorbed into the larger communities that now make up Alamance County.[32]

- Albright - site located approximately 1-mile (1.6 km) south of exit 153 on Interstate 40

- Carney - Near the site of Cedarock Park

- Cane Creek

- Cedarcliff - between Swepsonville and Saxapahaw

- Clover Orchard - approximately 2 miles (3.2 km) northeast of Snow Camp

- Curtis (Curtis Mills) - approximately 1/2 mile southeast of the village of Alamance

- Glenddale - approximately 3 miles (4.8 km) north of Pleasant Grove near the Alamance-Caswell county line

- Hartshorn - about 1½ miles south-southeast of the Alamance Battleground Historic Site

- Holmans Mills - approximately 1-mile (1.6 km) east of Snow Camp

- Iola - about 3 miles (4.8 km) east of Altamahaw, nearly due north of Glencoe

- Lacey - about 1-mile (1.6 km) east of Eli Whitney

- Leota - approximately 1-mile (1.6 km) south of Eli Whitney

- Loy - at the northern base of Bass Mountain

- Manndale

- Maywood - approximately 3 miles (4.8 km) northeast of Altamahaw

- McCray (McRay) - about 2 miles (3.2 km) east-northeast of Glencoe

- Melville - approximately 2 miles (3.2 km) west-southwest of the intersection of Interstate 40 and NC Highway 119

- Morton's Store - approximately 2 miles (3.2 km) north of Altamahaw

- Nicholson - near the intersection of NC Highway 87 and Bellemont-Mount Hermon Road

- Oakdale - in the southwest of the county, near the intersection of NC Highway 49 and Greensboro-Chapel Hill Road

- Oneida

- Osceola

- Pleasant Grove - in the far northeast part of the county, 2 miles (3.2 km) east-northeast of the current Pleasant Grove

- Pleasant Lodge - 1-mile (1.6 km) to the west of the site of Oakdale, near the Alamance-Guilford county line

- Rock Creek - 4 miles (6.4 km) due south of Alamance

- Shallow Ford - 1-mile (1.6 km) east of Ossipee

- Shady Grove

- Stainback - about 2 miles (3.2 km) east-northeast of Green Level

- Sutpin - on the same latitude as Snow Camp, approximately halfway between Snow Camp and Eli Whitney

- Sylvester

- Union Ridge - near the east bank of Lake Cammack, about 3 miles (4.8 km) from the Alamance-Caswell county line

- Vincent - 2 miles (3.2 km) north-northeast of Pleasant Grove

Population ranking

The population ranking of the following table is based on the 2010 census of Alamance County.[33]

† county seat

| Rank | City/Town/etc. | Municipal type | Population (2010 Census) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Burlington (partially in Guilford County) | City | 49,963 |

| 2 | † Graham | City | 14,153 |

| 3 | Mebane (partially in Orange County) | City | 11,393 |

| 4 | Elon | Town | 9,419 |

| 5 | Gibsonville (mostly in Guilford County) | Town | 6,410 |

| 6 | Glen Raven | CDP | 2,750 |

| 7 | Haw River | Town | 2,298 |

| 8 | Green Level | Town | 2,100 |

| 9 | Saxapahaw | CDP | 1,648 |

| 10 | Swepsonville | Town | 1,154 |

| 11 | Alamance | Village | 951 |

| 12 | Woodlawn | CDP | 900 |

| 13 | Ossipee | Town | 543 |

| 14 | Altamahaw | CDP | 347 |

Politics and government

Lying between overwhelmingly liberal and Democratic Orange County and Durham County to the east, equally Democratic Guilford County to the west, and heavily conservative and Republican Randolph County to the southwest, Alamance leans Republican, though not as overwhelmingly as many other suburban counties in the Piedmont Triad. The last Democratic nominee for president to carry Alamance County was Jimmy Carter in 1976.

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 53.5% 46,056 | 45.1% 38,825 | 1.4% 1,210 |

| 2016 | 54.6% 38,815 | 41.9% 29,833 | 3.5% 2,509 |

| 2012 | 56.3% 38,170 | 42.6% 28,875 | 1.1% 731 |

| 2008 | 54.2% 34,859 | 44.9% 28,918 | 0.9% 576 |

| 2004 | 61.5% 33,302 | 38.2% 20,686 | 0.4% 187 |

| 2000 | 62.2% 29,305 | 37.1% 17,459 | 0.7% 327 |

| 1996 | 53.7% 22,461 | 37.8% 15,814 | 8.6% 3,586 |

| 1992 | 48.3% 20,637 | 36.4% 15,521 | 15.3% 6,543 |

| 1988 | 65.5% 24,131 | 34.3% 12,642 | 0.2% 78 |

| 1984 | 69.7% 26,063 | 30.1% 11,230 | 0.2% 77 |

| 1980 | 53.1% 18,077 | 44.2% 15,042 | 2.8% 947 |

| 1976 | 41.9% 12,680 | 57.5% 17,371 | 0.6% 180 |

| 1972 | 74.6% 22,046 | 23.1% 6,833 | 2.3% 670 |

| 1968 | 36.5% 12,310 | 24.5% 8,241 | 39.0% 13,139 |

| 1964 | 49.6% 15,177 | 50.4% 15,397 | |

| 1960 | 52.1% 14,818 | 47.9% 13,599 | |

| 1956 | 52.4% 12,123 | 47.6% 11,029 | |

| 1952 | 45.9% 11,388 | 54.1% 13,402 | |

| 1948 | 33.3% 5,124 | 53.9% 8,287 | 12.8% 1,969 |

| 1944 | 35.1% 4,976 | 64.9% 9,184 | |

| 1940 | 22.8% 3,382 | 77.2% 11,429 | |

| 1936 | 25.9% 3,847 | 74.1% 11,025 | |

| 1932 | 34.8% 4,478 | 64.0% 8,240 | 1.3% 164 |

| 1928 | 61.5% 6,810 | 38.5% 4,260 | |

| 1924 | 39.4% 3,217 | 59.5% 4,859 | 1.1% 93 |

| 1920 | 46.8% 4,619 | 53.2% 5,255 | |

| 1916 | 47.9% 2,278 | 52.0% 2,476 | 0.1% 5 |

| 1912 | 3.8% 150 | 54.3% 2,132 | 41.9% 1,647 |

| 1908 | 50.4% 2,184 | 48.8% 2,113 | 0.8% 34 |

| 1904 | 48.1% 1,770 | 51.8% 1,907 | 0.1% 2 |

| 1900 | 53.5% 2,256 | 45.6% 1,923 | 0.9% 38 |

| 1896 | 49.6% 2,314 | 49.3% 2,302 | 1.1% 50 |

| 1892 | 37.7% 1,301 | 49.0% 1,691 | 13.3% 458 |

| 1888 | 45.3% 1,544 | 50.4% 1,716 | 4.3% 148 |

| 1884 | 43.7% 1,259 | 55.7% 1,607 | 0.6% 18 |

| 1880 | 45.4% 1,247 | 53.3% 1,463 | 1.2% 34 |

Alamance County is a member of the regional Piedmont Triad Council of Governments. The county is led by the Alamance County Board of Commissioners and the County Manager, who is appointed by the Board of Commissioners. County residents also elect two other county government offices: the Sheriff and Register of Deeds.

| Elected officials of Alamance County as of 2019 | ||

| Official | Position | Term ends |

| County Commissioners | ||

| Amy Scott Galey | Chair | 2022 |

| Eddie Boswell | Vice-Chair | 2020 |

| William "Bill" Lashley | Commissioner | 2020 |

| Steve Carter | Commissioner | 2022 |

| Tim Sutton | Commissioner | 2020 |

| Other County-Wide Offices | ||

| Terry Johnson | Sheriff | 2018 |

| Hugh Webster | Register of Deeds | 2020 |

Alamance County has provided North Carolina with three of its governors and two U. S. senators: Governor Thomas Holt, Governor and U. S. Senator Kerr Scott, Governor Robert W. (Bob) Scott (Kerr Scott's son), and U. S. Senator B. Everett Jordan.

County manager

Alamance County adopted the council-manager form of government in the 1970s, where the day-to-day management of county business is done by an individual hired by the commissioners' board. Since the establishment of the office, the following persons have served as county managers:

Current manager

Bryan Hagood (March 2017-present).[36]

Past managers

- Craig Honeycutt (April 2009 - March 2017)

- David I. Smith (August 2005 - December 2008)

- David S. Cheek (July 1998 - June 2005)

- Robert C. Smith

- Hal Larry Scott

- D. J. Walker

Walker and David Smith held dual roles as county manager and county attorney during their terms.

Arts and recreation

The arts

The Paramount Theater serves as a center of dramatic presentations in the community. To the south there is the Snow Camp Outdoor Drama which has plays from late spring to early fall in the evenings. Alamance County is also home to the Haw River Ballroom, a large music and arts venue in Saxapahaw.

Parks

Alamance County, Burlington, Graham, Elon, Haw River, Swepsonville, and Mebane all have small parks that are not listed here. Major parks include:

- Cedarock Park, located 6 miles (10 km) south of the intersection of Interstate 85/40 and NC Highway 49. The park is home to the Cedarock Historic Farm, an old mill dam, and two disc golf courses.

- Great Bend Park at Glencoe, located 4 miles (6 km) north of the intersection of US Highway 70, and NC Highways 87, 62, and 100 in downtown Burlington. Great Bend Park contains parts of the Haw River Land and Paddle Trails and the Mountains-to-Sea Trail, along with picnicking, fishing, and other opportunities. The park was built around the site of the Glencoe Mills, an area that is currently under renovation with an old mill that has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Professional

The Burlington Royals are a rookie league baseball farm team based in Burlington. They were previously known as the Burlington Indians, but changed affiliations in 2006 from Cleveland to Kansas City. This version of the team has been active since 1985, but Burlington hosted a minor league baseball team for many years under the Burlington Indians and Burlington Bees.

Collegiate

The Elon University Phoenix play in the town of Elon. The Phoenix compete in the NCAA's Division I (Championship Subdivision in football) Colonial Athletic Association. Intercollegiate sports include baseball, basketball, cross-country, football, golf, soccer, and tennis for men, and basketball, cross-country, golf, indoor track, outdoor track, soccer, softball, tennis, and volleyball for women.

Economy

Today, Alamance County is often described as a "bedroom" community, with many residents living in the county and working elsewhere due to low tax rates, although the county is still a major player in the textile and manufacturing industries. The current county-wide tax rate for Alamance County residents is 58.0 cents per $100 valuation. This does not include tax rates imposed by municipalities or fire districts.

The top employers in Alamance County are:

| Company | City | Location type | Employees |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alamance-Burlington School System | Burlington | HQ | 3,329 |

| Laboratory Corp of America | Burlington | HQ | 3,200 |

| Alamance Regional Medical Center | Burlington | HQ | 2,240 |

| Elon University | Elon | Main Campus | 1,403 |

| Wal-Mart | Burlington | Branch | 1,000 |

| Alamance County | Graham | HQ | 956 |

| City of Burlington | Burlington | HQ | 806 |

| Alamance Community College | Graham | HQ | 652 |

| Honda Power Equipment Mfg | Swepsonville | HQ | 600 |

| GKN Driveline North America | Mebane | Branch | 500 |

| Glen Raven Inc. | Altamahaw | Branch | 500 |

Education

Alamance County is served by the Alamance-Burlington School System, several private elementary and secondary schools, Alamance Community College, and Elon University.

Transportation

Alamance County has several state and federal highways running through it.

Interstates and U.S. highways

Going east-west in the county:

Interstate 85 / Interstate 40 (concurrent), also known as the Sam Hunt Freeway, named after a former North Carolina Secretary of Transportation. Interstates 85/40 run east-to-west through the central part of the county.

Interstate 85 / Interstate 40 (concurrent), also known as the Sam Hunt Freeway, named after a former North Carolina Secretary of Transportation. Interstates 85/40 run east-to-west through the central part of the county. U.S. Highway 70. Highway 70 nearly parallels 85/40 a few miles north of the interstates as it passes through the downtown sections of Burlington, Haw River, and Mebane.

U.S. Highway 70. Highway 70 nearly parallels 85/40 a few miles north of the interstates as it passes through the downtown sections of Burlington, Haw River, and Mebane.

N.C. state highways

N.C. Highway 49 runs southwest to northeast from the Liberty area (Randolph County), through Burlington, Graham, and Haw River, to the Pleasant Grove Community area, before turning northeast and continuing into Orange County.

N.C. Highway 49 runs southwest to northeast from the Liberty area (Randolph County), through Burlington, Graham, and Haw River, to the Pleasant Grove Community area, before turning northeast and continuing into Orange County. N.C. Highway 54 runs from its northwestern end at its intersection with U.S. Highway 70 in Burlington southeast to the Orange County line in the southeast part of the county.

N.C. Highway 54 runs from its northwestern end at its intersection with U.S. Highway 70 in Burlington southeast to the Orange County line in the southeast part of the county. N.C. Highway 62 runs southwest to northeast entering from Guilford County into Kimesville, then through Burlington, to Pleasant Grove. It then turns north and heads to Caswell County.

N.C. Highway 62 runs southwest to northeast entering from Guilford County into Kimesville, then through Burlington, to Pleasant Grove. It then turns north and heads to Caswell County. N.C. Highway 87 serves as the main north–south route through the county. It enters from the south at the Chatham County line into Eli Whitney, then through the major cities of Graham and Burlington, and a small part of Elon, before continuing north and heading through the Altamahaw-Ossipee area, finally moving into Caswell and Rockingham Counties.

N.C. Highway 87 serves as the main north–south route through the county. It enters from the south at the Chatham County line into Eli Whitney, then through the major cities of Graham and Burlington, and a small part of Elon, before continuing north and heading through the Altamahaw-Ossipee area, finally moving into Caswell and Rockingham Counties. N.C. Highway 100 forms a loop through downtown Burlington, starting at the intersection of Maple Avenue and Chapel Hill Road before moving north, then northwest, then going through Elon and moving on to Gibsonville and Guilford County.

N.C. Highway 100 forms a loop through downtown Burlington, starting at the intersection of Maple Avenue and Chapel Hill Road before moving north, then northwest, then going through Elon and moving on to Gibsonville and Guilford County. N.C. Highway 119 runs roughly north from its southern terminus at an intersection with N.C. Highway 54, moving through Mebane and heading north into Caswell County.

N.C. Highway 119 runs roughly north from its southern terminus at an intersection with N.C. Highway 54, moving through Mebane and heading north into Caswell County.

Notable people

- Jacob Brent, born in Graham, starred as "Mr. Mistoffelees" in the Broadway and movie version of Andrew Lloyd Webber's Cats

- Billy Bryan, Center for the Denver Broncos, from 1977 to 1988 grew up in Burlington.

- Several generations of Alex Haley's family may have lived in Alamance County, as noted in his 1976 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Roots: The Saga of an American Family - coming from Africa to Virginia, to Caswell County to Alamance County and moving to Tennessee after the Emancipation Proclamation.[37][38]

- Thomas Michael Holt, Governor of North Carolina from 1891 to 1893

- John "John Boy" Isley, born and raised in Graham, "John Boy" of the John Boy and Billy Show

- Charley Jones, born in Alamance County, Major League Baseball player[39]

- B. Everett Jordan, U. S. senator (Class 2) from 1958 to 1973

- Don Kernodle, born in Burlington, five-time NWA champion and tag team partner of Sgt Slaughter; appeared in Paradise Alley with Sylvester Stallone

- Jack McKeon, manager of the 2003 World Series champion Florida Marlins

- Blanche Taylor Moore, convicted murderer, whose life story was portrayed in the television movie "Black Widow: The Blanche Taylor Moore Story", starring Elizabeth Montgomery

- Meg Scott Phipps, North Carolina Agriculture Commissioner (2001–2003)

- Tequan Richmond, born in Burlington, stars as Drew Rock in Everybody Hates Chris, and played a young Ray Charles in the movie Ray

- Jeanne Robertson, humorist and professional speaker

- Robert W. (Bob) Scott (Kerr Scott's son), Governor of North Carolina from 1969 to 1973

- W. Kerr Scott, Governor of North Carolina from 1949 to 1953, U. S. senator (Class 2) from 1954 to 1958

- Brandon Tate, born in Burlington, American football wide receiver for the Cincinnati Bengals of the National Football League

- Will Richardson American football Offensive Linemen for the Jacksonville Jaguars of the National Football League

References

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". U.S. Census Bureau. March 28, 2020. Retrieved March 28, 2020.

- Talk Like A Tarheel Archived June 22, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, from the North Carolina Collection's website at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Retrieved September 18, 2012.

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved October 17, 2013.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- John R. Swanton, "North Carolina Indian Tribes", Indian Tribes of North America, 1953, at Access Genealogy, accessed March 25, 2009

- "Sissipahaw Indian Tribe History", John R. Swanton, Indian Tribes of North America, 1953, at Access Genealogy, accessed March 25, 2009

- "The Trading Path in Alamance County, a Beginning", Alamance County Historical Association, Trading Path Association: Preserving our Common Past

- "North Carolina Counties - List of all and Alamance County". Archived from the original on October 21, 2009.

- "Hadley Society Photo Gallery". hadleysociety.org. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2007.

- "The Battle of Clapp's Mills". revolutionarywar101.com.

- "Occaneechi Band of the Saponi Nation". Southern Neighbor. November 2009.

- "Alamance County, NC". textilehistory.org. Archived from the original on February 16, 2012.

- "Marker: G-82". ncmarkers.com. Archived from the original on July 11, 2015. Retrieved June 14, 2010.

- Alamance County Historical Museum, Burlington, North Carolina Archived April 15, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- "Alamance County North Carolina Genealogy - Family History Resources". kindredtrails.com. Archived from the original on March 29, 2013. Retrieved January 15, 2006.

- http://members.aol.com/jweaver303/nc/convvote.htm

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 4, 2008. Retrieved August 13, 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Economic Development". www.cityofmebane.com. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-releases-investigative-findings-alamance-county-nc-sheriff-s-office

- sarah.williamson@greensboro.com, Sarah Newell Williamson. "U.S. District Court judge dismisses lawsuit against Alamance County sheriff". Greensboro News and Record. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- "9 arrested while protesting Alamance County's contract with ICE, organizers say". myfox8.com. November 25, 2019. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- https://www.newsobserver.com/article246861942.html

- WRAL (November 2, 2020). "Alamance sheriff's office: Gas can, generator created danger during march to polls :". WRAL.com. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Archived from the original on January 12, 2015. Retrieved January 11, 2015.

- GIS System Contours found on the Alamance County Website

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved March 28, 2020.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 11, 2015.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved January 11, 2015.

- Forstall, Richard L., ed. (March 27, 1995). "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 11, 2015.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 11, 2015.

- Data Access and Dissemination Systems (DADS). "U.S. Census website". census.gov.

- Burlington Times-News, December 11, 1975

- Promotions, Center for New Media and. "US Census Bureau 2010 Census". www.census.gov. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- http://geoelections.free.fr/. Retrieved January 13, 2021. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Times-News, Burlington. "Alamance County commissioners hire Hagood as new county manager". Greensboro News and Record. Retrieved June 21, 2019.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on October 7, 2008. Retrieved August 23, 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Cross Roads History". rootsweb.com.

- Reichler, Joseph L., ed. (1979) [1969]. The Baseball Encyclopedia (4th ed.). New York: Macmillan Publishing. ISBN 0-02-578970-8.

Further reading

- Beatty, Bess. Alamance: The Holt Family and Industrialization in a North Carolina County, 1837-1900 (LSU Press, 1999).

- Bissett, Jim, “The Dilemma over Moderates: School Desegregation in Alamance County, North Carolina,” Journal of Southern History, 81 (Nov. 2015), 887–930.

- Gant, Margaret Elizabeth. "The Episcopal Church in Burlington, 1879-1979: one hundred years of history." (2014). online

- Pierpont, Andrew Warren. Development of the textile industry in Alamance County, North Carolina (1953).

- Troxler, Carole Watterson. Shuttle and Plow: A History of Alamance County, North Carolina (1999).

- Whitaker, Walter E. Centennial History of Alamance County 1849-1949 (Burlington Chamber of Commerce, 1949).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alamance County, North Carolina. |