Buncombe County, North Carolina

Buncombe County is a county located in the U.S. state of North Carolina. It is classified within Western North Carolina. The 2010 census reported the population was 238,318.[1] Its county seat is Asheville.[2]

Buncombe County | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Buncombe County Courthouse in Asheville | |

Seal | |

Location within the U.S. state of North Carolina | |

North Carolina's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 35°37′N 82°32′W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | 1791 |

| Named for | Edward Buncombe |

| Seat | Asheville |

| Largest city | Asheville |

| Area | |

| • Total | 660 sq mi (1,700 km2) |

| • Land | 657 sq mi (1,700 km2) |

| • Water | 3.5 sq mi (9 km2) 0.5%% |

| Population | |

| • Estimate (2019) | 261,191 |

| • Density | 363/sq mi (140/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Congressional district | 11th |

| Website | www |

Buncombe County is part of the Asheville, NC Metropolitan Statistical Area.

History

Buncombe County was organized by European Americans after the Revolutionary War in the home of Col. William Davidson, a cousin of William Lee Davidson and elected as the county's first state senator.[3] The first meeting of the county government took place in April 1792 in Col. Davidson's barn (located on the present-day Biltmore Estate).[4]

At first, deeds were recorded in Morganton, the nearest county seat. This was inconvenient for residents as roads were poor. In December 1792 seven men met to select a courthouse location for the county. The first courthouse was built at the present-day Pack Square site in Asheville.[5]

The county was formed in 1791 from parts of Burke and Rutherford counties. It was named for Edward Buncombe, a colonel in the American Revolutionary War, who was captured at the Battle of Germantown.[6][7] The large county originally extended to the Tennessee line.

Many of the early settlers were Baptists. In 1807 the pastors of six churches, including the revivalist Sion Blythe, formed the French Broad Association of Baptist churches in the area.[8]

As population increased in this part of the state, parts of the county were taken to organize new counties. In 1808 the western part of Buncombe County became Haywood County. In 1833 parts of Burke and Buncombe counties were combined to form Yancey County. In 1838 the southern part of what was left of Buncombe County became Henderson County. In 1851 parts of Buncombe and Yancey counties were combined to form Madison County. Finally, in 1925 the Broad River township of McDowell County was transferred to Buncombe County.

In 1820, a U.S. Congressman whose district included Buncombe County, unintentionally contributed a word to the English language. In the Sixteenth Congress, after lengthy debate on the Missouri Compromise, members of the House called for an immediate vote on that important question. Felix Walker rose to address his colleagues, insisting that his constituents expected him to make a speech "for Buncombe." It was later remarked that Walker's untimely and irrelevant oration was not just for Buncombe—it "was Buncombe." Buncombe, afterwards spelled bunkum and later shortened to bunk, became a term for empty, nonsensical talk.[9] This, in turn, is the etymology of the verb debunk.

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Buncombe county has a total area of 660 square miles (1,700 km2), of which 657 square miles (1,700 km2) is land and 3.5 square miles (9.1 km2) (0.5%) is water.[10]

The French Broad River enters the county at its border with Henderson County to the south and flows north into Madison County. The source of the Swannanoa River, which joins the French Broad River in Asheville, is in northeast Buncombe County near Mount Mitchell, a part of the range known as the Black Mountains. Mt. Mitchell is the highest point in the eastern United States at 6,684 ft.[11]

A milestone was achieved in 2003 when Interstate 26, still called Future I-26 in northern Buncombe County, was extended from Mars Hill (north of Asheville) to Johnson City, Tennessee. This completed a 20-year, half-billion dollar construction project through the Blue Ridge Mountains.

Adjacent counties

- Madison County - north

- Yancey County - northeast

- McDowell County - east

- Rutherford County - southeast

- Henderson County - south

- Transylvania County - southwest

- Haywood County - west

Major highways

National protected areas

- Blue Ridge Parkway (part)

- Pisgah National Forest (part)

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1800 | 5,812 | — | |

| 1810 | 9,277 | 59.6% | |

| 1820 | 10,542 | 13.6% | |

| 1830 | 16,281 | 54.4% | |

| 1840 | 10,084 | −38.1% | |

| 1850 | 13,425 | 33.1% | |

| 1860 | 12,654 | −5.7% | |

| 1870 | 15,412 | 21.8% | |

| 1880 | 21,909 | 42.2% | |

| 1890 | 35,266 | 61.0% | |

| 1900 | 44,288 | 25.6% | |

| 1910 | 49,798 | 12.4% | |

| 1920 | 64,148 | 28.8% | |

| 1930 | 97,937 | 52.7% | |

| 1940 | 108,755 | 11.0% | |

| 1950 | 124,403 | 14.4% | |

| 1960 | 130,074 | 4.6% | |

| 1970 | 145,056 | 11.5% | |

| 1980 | 160,934 | 10.9% | |

| 1990 | 174,821 | 8.6% | |

| 2000 | 206,330 | 18.0% | |

| 2010 | 238,318 | 15.5% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 261,191 | [12] | 9.6% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[13] 1790–1960[14] 1900–1990[15] 1990–2000[16] 2010–2013[1] | |||

Since 1970, the county has had a steady rise in population, attracting retirees, second-home buyers and others from outside the region. As of the census[17] of 2000, there were 206,330 people, 85,776 households, and 55,668 families residing in the county. The population density was 314 people per square mile (121/km2). There were 93,973 housing units at an average density of 143 per square mile (55/km2). The racial makeup of the county was 89.06% White, 7.48% Black or African American, 0.39% Native American, 0.66% Asian, 0.04% Pacific Islander, 1.15% from other races, and 1.23% from two or more races. 2.78% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 85,776 households, out of which 27.50% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 50.50% were married couples living together, 10.80% had a female householder with no husband present, and 35.10% were non-families. Of all households 28.90% were made up of individuals, and 10.60% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.33 and the average family size was 2.86.

In the county, the population was spread out, with 21.90% under the age of 18, 8.60% from 18 to 24, 29.30% from 25 to 44, 24.80% from 45 to 64, and 15.40% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 39 years. For every 100 females there were 92.30 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 88.90 males.

The median income for a household in the county was $36,666, and the median income for a family was $45,011. Males had a median income of $30,705 versus $23,870 for females. The per capita income for the county was $20,384. About 7.80% of families and 11.40% of the population were below the poverty line, including 15.30% of those under age 18 and 9.80% of those age 65 or over.

Politics, law and government

Local government

Buncombe County is a member of the Land-of-Sky Regional Council of governments.

Buncombe County has a council/manager form of government. Current commissioners were elected in 2014: Brownie Newman, Mike Fryar, Ellen Frost, Joe Belcher, Miranda DeBruhl, Holly Jones, and chair David Gantt.[18] The county manager is Wanda Greene.

The North Carolina Department of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention formerly operated the Swannanoa Valley Youth Development Center in Swannanoa for delinquent boys, including those without sufficient English fluency. It opened in 1961.[19]

Sheriff's Office and policing

The Buncombe County Sheriff provides court protection and jail administration for the entire county and provides patrol and detective services for the unincorporated areas of the county. The Sheriff's Office is organized into five divisions: Enforcement, Detention, Animal Control, Support Operations, School Resources, Civil Process.[20] Asheville also has a municipal police department.[21]

State government

In the North Carolina Senate, Terry Van Duyn (D-Asheville) and Chuck Edwards (R-Hendersonville) both represent parts of Buncombe County. Van Duyn represents most of the city of Asheville. Edwards represents a small portion of the southern part of Asheville.

In the North Carolina House of Representatives, Susan Fisher (D-Asheville), John Ager (D-Fairview), and Brian Turner (D-Asheville) all represent parts of the county. All three of them represent parts of the city, although the majority of it is in Fisher's district.

Federal government

Buncombe had long been a bellwether county in presidential elections. It voted for the winning candidate in every election from 1928 to 2012, except for that of 1960.

Since 2008, the county has trended strongly toward the Democratic Party. It swung from a 0.6 point win for George W. Bush to a 14-point win for Barack Obama in 2008, and has gone Democratic by double-digit margins at every election since then. This includes 2016, when it voted for Hillary Clinton. When Donald Trump won the electoral college (and the election) after losing the popular vote, the county lost its bellwether status. In 2020, Joe Biden's performance in the county was the best by a Democrat since Lyndon Johnson's 1964 landslide.

North Carolina is represented in the United States Senate by Republicans Richard Burr and Thom Tillis, from Winston-Salem and Greensboro, respectively. The city of Asheville is included within North Carolina's 11th congressional district. The seat was vacant after the resignation of Republican Mark Meadows on March 30, 2020, after he was appointed as President Trump's Chief of Staff. The incumbent is Madison Cawthorn.

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 38.6% 62,412 | 59.7% 96,515 | 1.6% 2,642 |

| 2016 | 40.1% 55,716 | 54.3% 75,452 | 5.6% 7,779 |

| 2012 | 42.8% 54,701 | 55.3% 70,625 | 1.9% 2,370 |

| 2008 | 42.4% 52,494 | 56.3% 69,716 | 1.3% 1,585 |

| 2004 | 50.0% 52,491 | 49.4% 51,868 | 0.6% 654 |

| 2000 | 53.9% 46,101 | 45.1% 38,545 | 1.0% 830 |

| 1996 | 44.2% 30,518 | 45.8% 31,658 | 10.0% 6,891 |

| 1992 | 40.9% 30,892 | 43.7% 32,955 | 15.4% 11,645 |

| 1988 | 57.6% 36,828 | 42.1% 26,964 | 0.3% 200 |

| 1984 | 61.6% 37,698 | 38.1% 23,337 | 0.2% 148 |

| 1980 | 48.8% 26,124 | 46.4% 24,837 | 4.8% 2,569 |

| 1976 | 45.5% 22,461 | 53.9% 26,633 | 0.6% 285 |

| 1972 | 70.4% 32,091 | 27.7% 12,626 | 1.9% 877 |

| 1968 | 44.2% 21,031 | 30.8% 14,624 | 25.0% 11,889 |

| 1964 | 38.0% 19,372 | 62.0% 31,623 | |

| 1960 | 54.6% 28,040 | 45.4% 23,303 | |

| 1956 | 54.3% 22,655 | 45.7% 19,044 | |

| 1952 | 52.2% 24,444 | 47.9% 22,425 | |

| 1948 | 37.2% 11,460 | 55.3% 17,072 | 7.5% 2,319 |

| 1944 | 31.0% 9,398 | 69.0% 20,878 | |

| 1940 | 26.0% 8,723 | 74.0% 24,878 | |

| 1936 | 28.6% 9,470 | 71.4% 23,646 | |

| 1932 | 32.0% 8,745 | 66.7% 18,241 | 1.3% 367 |

| 1928 | 57.2% 16,590 | 42.8% 12,405 | |

| 1924 | 37.3% 6,285 | 59.9% 10,098 | 2.8% 467 |

| 1920 | 44.1% 8,017 | 55.9% 10,167 | |

| 1916 | 47.5% 3,830 | 52.5% 4,229 | |

| 1912 | 6.5% 426 | 56.9% 3,716 | 36.6% 2,386 |

| 1908 | 50.0% 3,572 | 49.1% 3,506 | 0.8% 62 |

| 1904 | 44.7% 2,591 | 54.8% 3,181 | 0.4% 24 |

| 1900 | 52.4% 4,140 | 47.1% 3,724 | 0.4% 35 |

| 1896 | 52.8% 4,611 | 46.9% 4,098 | 0.2% 24 |

| 1892 | 44.1% 3,125 | 50.7% 3,588 | 5.0% 360 |

| 1888 | 48.2% 2,873 | 49.6% 2,956 | 2.0% 121 |

| 1884 | 42.8% 2,007 | 56.5% 2,649 | 0.5% 26 |

| 1880 | 44.3% 1,591 | 55.6% 1,995 | 0.0% 0 |

Communities

City

- Asheville (county seat)

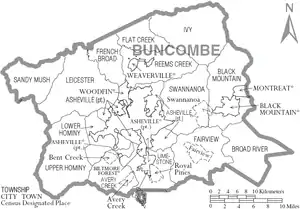

Townships

- Asheville

- Avery Creek

- Black Mountain

- Broad River

- Fairview

- Flat Creek

- French Broad

- Hazel [23]

- Ivy

- Leicester

- Limestone

- Lower Hominy

- Reems Creek

- Sandy Mush

- Swannanoa

- Woodfin

- Upper Hominy

Census-designated places

Unincorporated communities

Public libraries

Buncombe County Public Libraries has 11 branch locations, with a central location at Pack Memorial Library in downtown Asheville.[24]

See also

References

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved October 17, 2013.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on 2011-05-31. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- "William Davidson Confusion Continues". November 17, 2014. Retrieved November 8, 2018.

- Neufeld, Rob (August 18, 2019). "Visiting Our Past: Roads, orphans, speculation and missing ears occupied first settlers". Asheville Citizen-Times. Retrieved 2019-08-18.

- Neufeld, Rob (August 11, 2019). "Visiting Our Past: Alcohol drinking helped Asheville planners in 1792". Asheville Citizen-Times. Retrieved 2019-08-11.

- J.D. Lewis. NC Patriots 1775–1783: Their Own Words, Volume 1. JD Lewis. pp. 54–. ISBN 978-1-4675-4808-3.

- Best Books on (1939). North Carolina, a Guide to the Old North State,. Best Books on. pp. 496–. ISBN 978-1-62376-032-8.

- David Benedict (1813). "NORTH-CAROLINA". A GENERAL HISTORY OF THE BAPTIST DENOMINATION IN AMERICA, AND OTHER PARTS OF THE WORLD. Lincoln & Edmands. Retrieved 2010-08-29.

- debunk – The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition. 2000 Archived April 6, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Houghton Mifflin, Boston, accessed 2009-01-11

- "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Archived from the original on January 12, 2015. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

- http://www.ncparks.gov › mount-mitchell-state-park

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved March 28, 2020.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

- Forstall, Richard L., ed. (March 27, 1995). "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. April 2, 2001. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "Buncombe County – County Commissioners". www.buncombecounty.org. Retrieved 2018-03-14.

- "Swannanoa Valley YDC" (). North Carolina Department of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. April 28, 2006. Retrieved on December 16, 2015.

- https://www.buncombecounty.org/governing/depts/sheriff/

- https://www.ashevillenc.gov/department/police/

- Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved 2018-03-14.

- though not listed on the census map below, it shows up here: https://www.buncombecounty.org/common/landRecords/mappers_townships.pdf

- "Libraries - Branch Locations". www.buncombecounty.org. Retrieved 2019-11-25.

External links

- Official website

- NCGenWeb Buncombe County – free genealogy resources for the county