Glass ceiling

A glass ceiling is a metaphor used to represent an invisible barrier that prevents a given demographic (typically applied to minorities) from rising beyond a certain level in a hierarchy.[1]

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

The metaphor was first coined by feminists in reference to barriers in the careers of high-achieving women.[2][3] In the US, the concept is sometimes extended to refer to obstacles hindering the advancement of minority women, as well as minority men.[2][4] Minority women in white-majority countries often find the most difficulty in "breaking the glass ceiling" because they lie at the intersection of two historically marginalized groups: women and people of color.[5] East Asian and East Asian American news outlets have coined the term "bamboo ceiling" to refer to the obstacles that all East Asian Americans face in advancing their careers.[6][7] Similarly, a set of invisible obstacles posed against refugees' efforts to workforce integration has been coined the "canvas ceiling".

Within the same concepts of the other terms surrounding the workplace, there are similar terms for restrictions and barriers concerning women and their roles within organizations and how they coincide with their maternal duties. These "Invisible Barriers" function as metaphors to describe the extra circumstances that women undergo, usually when trying to advance within areas of their careers and often while trying to advance within their lives outside their work spaces.[8]

"A glass ceiling" represents a barrier that prohibits women from advancing toward the top of a hierarchical corporation. Those women are prevented from receiving promotion, especially to the executive rankings, within their corporation. In the last twenty years, the women who have become more involved and pertinent in industries and organizations have rarely been in the executive ranks. Women in most corporations encompass below five percent of board of directors and corporate officer positions.[9]

Definition

The United States Federal Glass Ceiling Commission defines the glass ceiling as "the unseen, yet unbreachable barrier that keeps minorities and women from rising to the upper rungs of the corporate ladder, regardless of their qualifications or achievements."[1]

David Cotter and colleagues defined four distinctive characteristics that must be met to conclude that a glass ceiling exists. A glass ceiling inequality represents:

- "A gender or racial difference that is not explained by other job-relevant characteristics of the employee."

- "A gender or racial difference that is greater at higher levels of an outcome than at lower levels of an outcome."

- "A gender or racial inequality in the chances of advancement into higher levels, not merely the proportions of each gender or race currently at those higher levels."

- "A gender or racial inequality that increases over the course of a career."

Cotter and colleagues found that glass ceilings are correlated strongly with gender, with both white and minority women facing a glass ceiling in the course of their careers. In contrast, the researchers did not find evidence of a glass ceiling for African-American men.[10]

The glass ceiling metaphor has often been used to describe invisible barriers ("glass") through which women can see elite positions but cannot reach them ("ceiling").[11] These barriers prevent large numbers of women and ethnic minorities from obtaining and securing the most powerful, prestigious and highest-grossing jobs in the workforce.[12] Moreover, this effect prevents women from filling high-ranking positions and puts them at a disadvantage as potential candidates for advancement.[13][14]

History

In 1839, French feminist and author George Sand used a similar phrase, une voûte de cristal impénétrable, in a passage of Gabriel, a never-performed play: "I was a woman; for suddenly my wings collapsed, ether closed in around my head like an impenetrable crystal vault, and I fell...." [emphasis added]. The statement, a description of the heroine's dream of soaring with wings, has been interpreted as a feminine Icarus tale of a woman who attempts to ascend above her accepted role.[15]

The first person said to use the term Glass ceiling was Marilyn Loden during a 1978 speech.[16][17][18] At the same time, according to the April 3, 2015, Wall Street Journal, completely independent of Loden, the term glass ceiling was coined in the spring of 1978 by Marianne Schriber and Katherine Lawrence at Hewlett-Packard.[19] The ceiling was defined as discriminatory promotion patterns where the written promotional policy is non-discriminatory, but in practice denies promotion to qualified females. Lawrence presented this at the annual Conference of the Women's Institute for Freedom of the Press at meeting the National Press.

The term was later used in March 1984 by Gay Bryant. She was the former editor of Working Woman magazine and was changing jobs to be the editor of Family Circle. In an Adweek article written by Nora Frenkel, Bryant was reported as saying, "Women have reached a certain point—I call it the glass ceiling. They're in the top of middle management and they're stopping and getting stuck. There isn't enough room for all those women at the top. Some are going into business for themselves. Others are going out and raising families."[20][21][22] Also in 1984, Bryant used the term in a chapter of the book The Working Woman Report: Succeeding in Business in the 1980s. In the same book, Basia Hellwig used the term in another chapter.[21]

In a widely cited article in the Wall Street Journal in March 1986 the term was used in the article's title: "The Glass Ceiling: Why Women Can't Seem to Break The Invisible Barrier That Blocks Them From the Top Jobs". The article was written by Carol Hymowitz and Timothy D. Schellhardt. Hymowitz and Schellhardt introduced glass ceiling was "not something that could be found in any corporate manual or even discussed at a business meeting; it was originally introduced as an invisible, covert, and unspoken phenomenon that existed to keep executive level leadership positions in the hands of Caucasian males."[23]

As the term "Glass Ceiling" became more common, the public responded with differing ideas and opinions. Some argued that the concept is a myth because women choose to stay home and showed less dedication to advance into executive positions.[23] As a result of continuing public debate, the US Labor Department's chief, Lynn Morley Martin, reported the results of a research project called "The Glass Ceiling Initiative", formed to investigate the low numbers of women and minorities in executive positions. This report defined the new term as "those artificial barriers based on attitudinal or organizational bias that prevent qualified individuals from advancing upward in their organization into management-level positions."[21][22]

In 1991, as a part of Title II of the Civil Right Act of 1991,[24] The United States Congress created the Glass Ceiling Commission. This 21 member Presidential Commission was chaired by Secretary of Labor Robert Reich,[24] and was created to study the "barriers to the advancement of minorities and women within corporate hierarchies[,] to issue a report on its findings and conclusions, and to make recommendations on ways to dis- mantle the glass ceiling."[1] The commission conducted extensive research including, surveys, public hearings and interviews, and released their findings in a report in 1995.[2] The report, "Good for Business", offered "tangible guidelines and solutions on how these barriers can be overcome and eliminated".[1] The goal of the commission was to provide recommendations on how to "shatter" the glass ceiling, specifically in the world of business. The report issued 12 recommendations on how to improve the workplace by increasing diversity in organizations and reducing discrimination through policy[1][25][26]

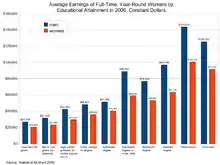

The number of women CEOs in the Fortune Lists has increased between 1998 and 2020,[27] despite women's labor force participation rate decreasing globally from 52.4% to 49.6% between 1995 and 2015. Only 19.2% of S&P 500 Board Seats were held by women in 2014, 80.2% of whom were considered white.[28]

Glass Ceiling Index

In 2017, the Economist updated their glass-ceiling index, combining data on higher education, labour-force participation, pay, child-care costs, maternity and paternity rights, business-school applications and representation in senior jobs.[29] The countries where inequality was the lowest were Iceland, Sweden, Norway, Finland, and Poland.

Gender stereotypes

In a 1993 report released through the U.S. Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences, researchers noted that although women have the same educational opportunities as their male counterparts, the Glass Ceiling persist due to systematic barriers, low representation and mobility, and stereotypes.[31] The perpetuation of sexist stereotypes is one widely recognized reason as to why female employees are systematically inhibited from receiving advantageous opportunities in their chosen fields.[32] A majority of Americans perceive women to be more emotional and men to be more aggressive than their opposite sex.[30] Gender stereotypes influence how leaders are chosen by employers and how workers of different sex are treated. Another stereotypes towards women in workplaces is the "gender status belief" which claims that men are more competent and intelligent than women, which would explain why they have higher positions in the career hierarchy. Ultimately, this factor leads to perception of gender-based jobs on the labor market, so men are expected to have more work-related qualifications and hired for top positions. [33] Perceived feminine stereotypes contribute to the glass ceiling faced by women in the workforce.

Hiring practices

When women leave their current place of employment to start their own businesses, they tend to hire other women. Men tend to hire other men. These hiring practices eliminate "the glass ceiling" because there is no more competition of capabilities and discrimination of gender. These support the segregated identification of "men's work" and "women's work."[34]

Cross-cultural context

Few women tend to reach positions in the upper echelon of society, and organizations are largely still almost exclusively lead by men. Studies have shown that the glass ceiling still exists in varying levels in different nations and regions across the world.[35][36][37] The stereotypes of women as emotional and sensitive could be seen as key characteristics as to why women struggle to break the glass ceiling. It is clear that even though societies differ from one another by culture, beliefs and norms, they hold similar expectations of women and their role in the society. These female stereotypes are often reinforced in societies that have traditional expectations of women.[35] The stereotypes and perceptions of women are changing slowly across the world, which also reduces gender segregation in organizations.[38][36]

Related concepts

"Glass escalator"

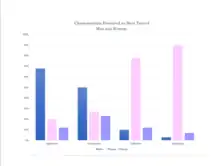

A parallel phenomenon called the "glass escalator" has also been recognized. As more men join fields that were previously dominated by women, such as nursing and teaching, the men are promoted and given more opportunities compared to the women, as if the men were taking escalators and the women were taking the stairs.[39] The chart from Carolyn K. Broner shows an example of the glass escalator in favor of men for female-dominant occupations in schools.[40] While women have historically dominated the teaching profession, men tend to take higher positions in school systems such as deans or principals.

Men benefit financially from their gender status in historically female fields, often "reaping the benefits of their token status to reach higher levels in female-dominated work.[41]"

A 2008 study published in Social Problems found that sex segregation in nursing did not follow the "glass escalator" pattern of disproportional vertical distribution; rather, men and women gravitated towards different areas within the field, with male nurses tending to specialize in areas of work perceived as "masculine".[42] The article noted that "men encounter powerful social pressures that direct them away from entering female-dominated occupations (Jacobs 1989, 1993)". Since female-dominated occupations are usually characterized with more feminine activities, men who enter these jobs can be perceived socially as "effeminate, homosexual, or sexual predators".[42]

"Sticky floors"

In the literature on gender discrimination, the concept of "sticky floors" complements the concept of a glass ceiling. Sticky floors can be described as the pattern that women are, compared to men, less likely to start to climb the job ladder. Thereby, this phenomenon is related to gender differentials at the bottom of the wage distribution. Building on the seminal study by Booth and co-authors in European Economic Review,[43] during the last decade economists have attempted to identify sticky floors in the labour market. They found empirical evidence for the existence of sticky floors in countries such as Australia, Belgium, Italy, Thailand and the United States.[44]

"The frozen middle"

Similar to the sticky floor, the frozen middle describes the phenomenon of women's progress up the corporate ladder slowing, if not halting, in the ranks of middle management.[45] Originally the term referred to the resistance corporate upper management faced from middle management when issuing directives. Due to a lack of ability or lack of drive in the ranks of middle management these directives do not come into fruition and as a result the company's bottom line suffers. The term was popularized by a Harvard Business Review article titled "Middle Management Excellence".[46] Due to the growing proportion of women to men in the workforce, however, the term "frozen middle" has become more commonly ascribed to the aforementioned slowing of the careers of women in middle management.[47] The 1996 study "A Study of the Career Development and Aspirations of Women in Middle Management" posits that social structures and networks within businesses that favor "good old boys" and norms of masculinity exist based on the experiences of women surveyed.[48] According to the study, women who did not exhibit stereotypical masculine traits, (e.g. aggressiveness, thick skin, lack of emotional expression) and interpersonal communication tendencies were disadvantaged compared to their male peers.[49] As the ratio of men to women increases in the upper levels of management,[50] women's access to female mentors who could advise them on ways to navigate office politics is limited, further inhibiting upward mobility within a corporation or firm.[51] Furthermore, the frozen middle affects female professionals in western and eastern countries such as the United States and Malaysia, respectively,[52] as well as women in a variety of fields ranging from the aforementioned corporations to STEM fields.[53]

"Second shift"

The second shift focuses on the idea that women theoretically work a second shift in the manner of having a greater workload, not just doing a greater share of domestic work. All of the tasks that are engaged in outside the workplace are mainly tied to motherhood. Depending on location, household income, educational attainment, ethnicity and location. Data shows that women do work a second shift in the sense of having a greater workload, not just doing a greater share of domestic work, but this is not apparent if simultaneous activity is overlooked.[54] Alva Myrdal and Viola Klein as early as 1956 focused on the potential of both men and women working in settings that included paid and unpaid types of work environments. Research indicated that men and women could have equal time for activities outside the work environment for family and extra activities.[55] This "second shift" has also been found to have physical effects as well. Women who engage in longer hours of work in pursuit of family balance, often face increased mental health problesm such as depression and anxiety. Increased irritability, lower motivation and energy, and other emotional issues were also found to occur as well. The overall happiness of women can be improved if a balance of career and home responsibilities is found.[56]

"Mommy Track"

"Mommy Track" refers to women who disregard their careers and professional duties in order to satisfy the needs of their families. Women are often subject to long work hours that creates an imbalance within the work-family schedule.[57] There is research suggesting that women are able to function on a part-time professional schedule compared to others who worked full-time while still engaged in external family activities. The research also suggests flexible work arrangements allow for the achievement of a healthy work and family balance. A difference has also been discovered in the cost and amount of effort in childbearing amongst women in higher skilled positions and roles, as opposed to women in lower-skilled jobs. This difference leads to women delaying and postponing goals and career aspirations over a number of years.

"Concrete floor"

The term concrete floor has been used to refer to the minimum number or the proportion of women necessary for a cabinet or board of directors to be perceived as legitimate.[58]

See also

- Celluloid ceiling

- Equal Pay Day

- Equal pay for women

- Female labor force in the Muslim world

- Feminization of poverty

- Gender equality

- Gender inequality

- Gender pay gap

- Gender role

- Glass cliff

- Material feminism

- Mommy track

- Sex differences in humans

- Sexism

- Stained-glass ceiling

- Superwoman (sociology)

- Time bind

References

- Federal Glass Ceiling Commission. Solid Investments: Making Full Use of the Nation's Human Capital. Archived 2014-11-08 at the Wayback Machine Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Labor, November 1995, p. 13-15.

- Federal Glass Ceiling Commission. Good for Business: Making Full Use of the Nation's Human Capital. Archived 2014-08-10 at the Wayback Machine Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Labor, March 1995.

- Wiley, John (2012). The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Gender and Sexuality Studies. Vol. 5. John Wiley and Sons.

- http://www.washingtontimes.com, The Washington Times. "Hillary Clinton: 'As a white person,' I have to discuss racism 'every chance I get'".

- "Demarginalising the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Anti-discrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory, and Anti-racist Politics" by Kimberlé Crenshaw in Framing Intersectionality, edited by Helma Lutz et al. (Ashgate, 2011).

- Hyun, Jane (2005). Breaking the Bamboo Ceiling: Career Strategies for Asians. New York: HarperBusiness.

- "Top 10 Numbers that Show Why Pay Equity Matters to Asian American Women and Their Families". name. Retrieved 2016-05-03.

- Smith, Paul; Caputi, Peter (2012). "A Maze of Metaphors". Faculty of Health and Behavioral Sciences. 27: 436–448. doi:10.1108/17542411211273432 – via University of Wollongong Research Online.

- Bass, Bernard M.; Avolio, Bruce J. (24/1994). "Shatter the glass ceiling: Women may make better managers". Human Resource Management. 33 (4): 549–560. doi:10.1002/hrm.3930330405. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - Cotter, David A.; Hermsen, Joan M.; Ovadia, Seth; Vanneman, Reece (2001). "The glass ceiling effect" (PDF). Social Forces. 80 (2): 655–81. doi:10.1353/sof.2001.0091.

-

- Davies-Netzley, Sally A (1998). "Women above the Glass Ceiling: Perceptions on Corporate Mobility and Strategies for Success". Gender and Society. 12 (3): 340. doi:10.1177/0891243298012003006. JSTOR 190289.

- Hesse-Biber and Carter 2005, p. 77.

- Nevill, Ginny, Alice Pennicott, Joanna Williams, and Ann Worrall. Women in the Workforce: The Effect of Demographic Changes in the 1990s. London: The Industrial Society, 1990, p. 39, ISBN 978-0-85290-655-2.

- US Department of Labor. "Good for Business: Making Full Use of the Nation's Human Capital". Office of the Secretary. Archived from the original on 28 October 2011. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- Harlan, Elizabeth (2008). George Sand. Yale University Press. p. 256. ISBN 978-0-300-13056-0.

- BusinessNews Publishing (2013). Summary: Full Frontal PR: Review and Analysis of Laermer and Prichinello's Book. Primento. p. 6. ISBN 9782806243027.

- Marilyn Loden On Feminine Leadership. Pelican Bay Post. May 2011.

- "100 Women: 'Why I invented the glass ceiling phrase'". BBC News. 2017-12-12. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

- Zimmer, Ben. "The Phrase 'Glass Ceiling' Stretches Back Decades". WSJ. Retrieved 2020-01-04.

- Frenkiel, Nora (March 1984). "The Up-and-Comers; Bryant Takes Aim At the Settlers-In". Adweek. Magazine World. Special Report.

- Catherwood Library reference librarians (January 2005). "Question of the Month: Where did the term 'glass ceiling' originate?". Cornell University, ILR School. Retrieved June 30, 2013.

- Bollinger, Lee; O'Neill, Carole (2008). Women in Media Careers: Success Despite the Odds. University Press of America. pp. 9–10. ISBN 978-0-7618-4133-3.

- Wilson, Eleanor (September 4, 2014). "Diversity, Culture and the Glass Ceiling". Journal of Cultural Diversity. 21 (3): 83–9. PMID 25306838.

- Redwood, Rene A. (October 13, 1995). "Breaking The Glass Ceiling: Good for Business, Good for America". National Council of Jewish Women.

- Johns, Merida L. (January 1, 2013). "Breaking the Glass Ceiling: Structural, Cultural, and Organizational Barriers Preventing Women from Achieving Senior and Executive Positions". Perspectives in Health Information Management.

- Morrison, Ann; White, Randall P.; Velsor, Ellen Van (1982). Breaking The Glass Ceiling: Can Women Reach The Top Of America's Largest Corporations? Updated Edition. Beverly, MA: Personnel Decisions, Inc. pp. xii.

- Hinchliffe, Emma. "The number of female CEOs in the Fortune 500 hits an all-time record". Fortune. Fortune Media IP Limited. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- acostigan (2012-10-17). "Statistical Overview of Women in the Workforce". Catalyst. Retrieved 2016-05-03.

- "Daily chart: The best and worst places to be a working woman". The Economist.

- Newport, Frank (February 21, 2001). "Americans See Women as Emotional and Affectionate, Men As More Aggressive". Gallup.

- Felber, Helene R.; Bayless, J. A.; Tagliarini, Felicity A.; Terner, Jessica L.; Dugan, Beverly A. (1993). The Glass Ceiling: Potential Causes and Possible Solutions. U.S. Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences. doi:10.21236/ada278051. S2CID 29423552.

- Hill, Catherine. "Barriers and Bias: The Status of Women in Leadership". AAUW.

- URL=https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/29811/1/605208190.pdf%7Ctitle=Glass Ceiling Effect and Earnings - The Gender Pay Gap in Managerial Positions in Germany

- Preston, Jo Anne (January 1999). "Occupational gender segregation Trends and explanations". The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance. 39 (5): 611–624. doi:10.1016/S1062-9769(99)00029-0.

- Bullough, A.; Moore, F.; Kalafatoglu, T. (2017). "Research on women in international business and management: then, now, and next". Cross Cultural & Strategic Management. 24 (2): 211–230. doi:10.1108/CCSM-02-2017-0011.

- ILO (2015). Women in Business and Management: Gaining momentum. Geneva: International Labour Office.

- OECD (2017). The Pursuit of Gender Equality: An Uphill Battle. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Glass, C.; Cook, A. (2016). "Leading at the top: Understanding women's challenges above the glass ceiling". The Leadership Quarterly. 27 (1): 51–63. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2015.09.003.

- "A New Obstacle For Professional Women: The Glass Escalator". Forbes. Retrieved 2015-10-23.

- "MEN, WOMEN, & THE GLASS ESCALATOR". Women on Business. Retrieved 2015-10-23.

- Arnesen, Eric (2009). "Gender Inequality" (PDF). University Of Wisconsin Madison.

- Snyder, Karrie Ann; Green, Adam Isaiah (1 May 2008). "Revisiting the Glass Escalator: The Case of Gender Segregation in a Female Dominated Occupation". Social Problems. 55 (2): 271–299. doi:10.1525/sp.2008.55.2.271 – via socpro.oxfordjournals.org.

- Booth, A. L.; Francesconi, M.; Frank, J. (2003). "A sticky floors model of promotion, pay, and gender". European Economic Review. 47 (2): 295–322. doi:10.1016/S0014-2921(01)00197-0.

- Baert, S.; De Pauw, A.-S.; Deschacht, N. (2016). "Do Employer Preferences Contribute to Sticky Floors?". ILR Review. 69 (3): 714–736. doi:10.1177/0019793915625213.

- Martell, Richard F., et al. "Sex Stereotyping In The Executive Suite: 'Much Ado About Something'." Journal of Social Behavior & Personality (1998) 127-138. Web.

- Byrnes, Jonathan. "Middle Management Excellence." Harvard Business Review 5 Dec. 2005 pag. print

- Lyness, Karen S., and Donna E. Thompson. "Climbing The Corporate Ladder: Do Female And Male Executives Follow The Same Route?." Journal of Applied Psychology (2000) 86-101. Web.

- Wentling, Rose Mary. "Women In Middle Management: Their Career Development And Aspirations." Business Horizon (1992) 47. Web.

- Wentling, Rose Mary. "Women In Middle Management: Their Career Development And Aspirations." Business Horizon, p. 252 (1992) 47. Web.

- Helfat, Constance E., Dawn Harris, and Paul J. Wolfson. "The Pipeline To The Top: Women And Men In The Top Executive Ranks Of U.S. Corporations." Academy Of Management Perspectives (2006) 42-64. Web.

- Dezso, Cristian L., David Gaddis Ross, and Jose Uribe. "Is There An Implicit Quota On Women In Top Management? A Large-Sample Statistical Analysis." Strategic Management Journal (2016) 98-115. Web.

- Mandy Mok Kim, Man, Miha Skerlavaj, and Vlado Dimovski. "Is There A 'Glass Ceiling' For Mid-Level Female Managers?." International Journal of Management & Innovation (2009) 1-13. Web.

- Cundiff, Jessica, and Theresa Vescio. "Gender Stereotypes Influence How People Explain Gender Disparities In The Workplace." Sex Roles (2016): 126-138. Web.

- Craig, Lyn (2007). "is herre really a second shift, and if so, who does it? a time-diary investigation". Feminist Review. 86 (1): 149–170. doi:10.1057/palgrave.fr.9400339. JSTOR 30140855.

- Myrdal, Alva; Klein, Viola (1957). "Women's Two Roles: Home and Work". American Sociological Review. 20 (2): 250. doi:10.2307/2088886. JSTOR 2088886.

- Ahmad, Muhammad (2011). "Working women work–life conflict". Business Strategy Series. 12.

- Hill, E. Jeffery; Martinson, Vjkollca K.; Baker, Robin Zenger; Ferris, Maria (2004). "Beyond The Mommy Track: The Influence of New Concept Part-Time Work for Professional Women on Work and Family". Journal of Family and Economic Issues. 25: 121–136. doi:10.1023/B:JEEI.0000016726.06264.91.

- "There are three rules of Cabinet appointments". Wall Street Journal. November 25, 2016.

- Wiley, John. The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Gender and Sexuality Studies. Vol. 5. Chicester: John Wiley and Sons, 2012. Print

Bibliography

- Cholensky, Stephanie (2015). "The Gender Pay Gap: NO MORE EXCUSES!". Judgment & Decision Making. 10 (2): 15–16.

- Federal Glass Ceiling Commission (March 1995a). Good for business: Making full use of the nation's human capital (PDF) (Report). Washington DC: U.S. Department of Labor. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-08-10. Retrieved 2011-04-09.

- Fox, Mary; Hesse-Biber, Sharlene N. (1984). Women at work. Palo Alto, California: Mayfield Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-87484-525-9.

- Giele, Janet Z.; Stebbins, Leslie F (2003). Women and equality in the workplace a reference handbook. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-937-9.

- Hesse-Biber, Sharlene N.; Carter, Gregg L. (2005). Working women in America : split dreams. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-515047-6.

- Lyness, Karen S.; Thompson, Donna E. (June 1997). "Above the glass ceiling? A comparison of matched samples of female and male executives". Journal of Applied Psychology. American Psychological Association. 82 (3): 359–375. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.82.3.359. PMID 9190144. S2CID 25113738.

- National Partnership for Women and Families, comp. (April 2016). "America's Women and The Wage Gap" (PDF). Trade, Jobs and Wages. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- Ponnuswamy, Indra; Manohar, Hansa Lysander (September 2014). "Breaking the glass ceiling – a mixed methods study using Watkins and Marsick's learning organisation culture model". Asian Women. Research Institute of Asian Women (RIAW). 30 (3): 85–111. doi:10.14431/aw.2014.09.30.3.85.

- Redwood, Rene A. (October 13, 1995). "Breaking The Glass Ceiling: Good for Business, Good for America". National Council of Jewish Women.

- Schneps, Leila; Colmez, Coralie (2013), "Math error number 6: Simpson's paradox. The Berkeley sex bias case: discrimination detection", in Schneps, Leila; Colmez, Coralie (eds.), Math on trial: how numbers get used and abused in the courtroom, New York: Basic Books, pp. 107–120, ISBN 978-0-465-03292-1

- Snyder, Karrie Ann; Isaiah Green, Adam (2008). "Revisiting The Glass Escalator: The Case Of Gender Segregation In A Female Dominated Occupation". Social Problems. 55 (2): 271–299. doi:10.1525/sp.2008.55.2.271.

- Woodhams, Carol; Lupton, Ben; Cowling, Marc (2015). "The Presence Of Ethnic Minority And Disabled Men In Feminised Work: Intersectionality, Vertical Segregation And The Glass Escalator" (PDF). Sex Roles. 72 (7–8): 277–293. doi:10.1007/s11199-014-0427-z. hdl:10871/16156.

- Malpas, J., "Donald Davidson", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2012 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), <http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2012/entries/davidson/>. Web 2 May 2016.

- International Labor Rights Forum. (n.d.). Retrieved May 2, 2016, from http://www.laborrights.org/issues/women's-rights

- Hyun, Jane. Breaking the Bamboo Ceiling: Career Strategies for Asians. New York: HarperBusiness, 2005. Print.

- Wiley, John. The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Gender and Sexuality Studies. Vol. 5. Chicester: John Wiley and Sons, 2012. Print.

- "Top 10 Numbers that Show Why Pay Equity Matters to Asian American Women and Their Families". Retrieved 2016-05-01

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Glass ceiling |

- Catalyst research report (1996). Women in Corporate Leadership: Progr (2003). Women and Men in U.S. Corporate Leadership: Same Workplace, Different Realities?

- Catalyst. Women and Men in U.S. Corporate Leadership: Same Workplace, Different Realities? New York, N.Y.: Catalyst, 2004, ISBN 978-0-89584-247-3.

- Catalyst. 2010 Catalyst Census: Financial Post 500 Women Senior Officers and Top Earners.

- Federal Glass Ceiling Commission. Good for Business: Making Full Use of the Nation's Human Capital. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Labor, March 1995.

- Federal Glass Ceiling Commission. Solid Investments: Making Full Use of the Nation's Human Capital. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Labor, November 1995.

- Carvajal, Doreen. The Codes That Need to Be Broken. The New York Times, January 26, 2011.

- Cotter, David A.; Hermsen, Joan M.; Ovadia, Seth; Vanneman, Reece (2001). "The glass ceiling effect" (PDF). Social Forces. 80 (2): 655–81. doi:10.1353/sof.2001.0091.

- Effects of Glass Ceiling on Women Career Development in Private Sector Organizations – Case of Sri Lanka