Cooch Behar

Cooch Behar (/ˌkuːtʃ bɪˈhɑːr/), or Koch Bihar, is a city and a municipality in the Indian state of West Bengal. It is the headquarters of the Cooch Behar district. It is in the foothills of the Eastern Himalayas at 26°22′N 89°29′E. Cooch Behar is the only planned city in North Bengal region with remnants of royal heritage.[4] Being one of the main tourist destinations of West Bengal, housing the Cooch Behar Palace and Madan Mohan Temple, it has been declared a heritage city.[5] It is the maternal home of Maharani Gayatri Devi.

Cooch Behar

Koch Bihar | |

|---|---|

City | |

| |

| Nickname(s): City of Beauty | |

Cooch Behar Location in West Bengal, India  Cooch Behar Cooch Behar (India)  Cooch Behar Cooch Behar (Asia) | |

| Coordinates: 26°19′27.084″N 89°27′3.6″E | |

| Country | |

| State | West Bengal |

| District | Cooch Behar |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipality |

| • Body | Cooch Behar Municipality |

| Area | |

| • City | 8.29 km2 (3.20 sq mi) |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

| • City | 77,935 |

| • Density | 9,400/km2 (24,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 106,760 |

| Languages | |

| • Official | Bengali[2][3] |

| • Additional official | English[2] |

| • Regional | Bengali, Rajbanshi |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

| PIN | 736 101,736167,736207 |

| Telephone code | 03582 |

| Vehicle registration | WB-64/63 |

| Lok Sabha constituency | Cooch Behar (SC) |

| Vidhan Sabha constituency | Cooch Behar Uttar (SC), Cooch Behar Dakshin, Natabari |

| Website | coochbehar |

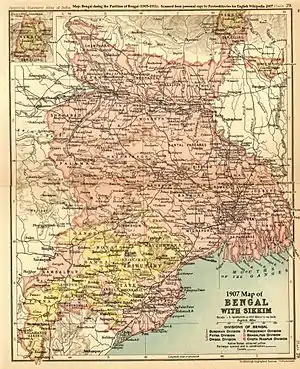

During the British Raj, Cooch Behar was the seat of the princely state of Koch Bihar, ruled by the Cooch Behar dynasty of often described as the Shiva Vansha, tracing their origin from the Koch tribe of North-eastern India. After 20 August 1949, Cooch Behar District was transformed from a princely state to its present status, with the city of Cooch Behar (Koch Behar) as its headquarters.[6]

Etymology

The name Cooch Behar is derived from the name of the Koch or Rajbongshi tribes.[7] The word behar is derived from Sanskrit: विहार vihara.

History

Early period

Cooch Behar formed part of the Kamarupa Kingdom of Assam from the 4th to the 12th centuries. In the 12th century, the area became a part of the Kamata Kingdom, first ruled by the Khen dynasty from their capital at Kamatapur. The Khens were an indigenous tribe, and they ruled till about 1498 CE, when they fell to Alauddin Hussain Shah, the independent Pathan Sultan of Gour. The new invaders fought with the local Bhuyan chieftains and the Ahom king Suhungmung and lost control of the region. During this time, the Koch tribe became very powerful and proclaimed itself Kamateshwar (Lord of Kamata) and established the Koch dynasty.

The first important Koch ruler was Biswa Singha, who came to power in 1510 or 1530 CE.[8] Under his son, Nara Narayan, the Kamata Kingdom reached its zenith.[9] Nara Narayan's younger brother, Shukladhwaj (Chilarai), was a noted military general who undertook expeditions to expand the kingdom. He became governor of its eastern portion.

After Chilarai's death, his son Raghudev became governor of this portion. Since Nara Narayan did not have a son, Raghudev was seen as the heir apparent. However, a late child of Nara Narayan removed Raghudev's claim to the throne. To placate him, Nara Narayan had to anoint Raghudev as a vassal chief of the portion of the kingdom east of the Sankosh river. This area came to be known as Koch Hajo. After the death of Nara Narayan in 1584, Raghudev declared independence. The kingdom ruled by the son of Nara Narayan, Lakshmi Narayan, came to be known as Koch Behar. The division of the Kamata Kingdom into Koch Behar and Koch Hajo was permanent. Koch Behar aligned itself with the Mughal Empire and finally joined the India as a part of the West Bengal, whereas remnants of the Koch Hajo rulers aligned themselves with the Ahom kingdom and the region became a part of Assam.

As the early capital of the Koch Kingdom, Koch Behar's location was not static and became stable only when shifted to Cooch Behar town. Maharaja Rup Narayan, on the advice of an unknown saint, transferred the capital from Attharokotha to Guriahati (now called Cooch Behar town) on the banks of the Torsa river between 1693 and 1714. After this, the capital was always in or near its present location.

In 1661 CE, Maharaja Pran Narayan planned to expand his kingdom. However, Mir Jumla, the subedar of Bengal under the Mughal emperor Aurangazeb, attacked Cooch Behar and conquered the territory, meeting almost no resistance.[10] The town of Cooch Behar was subsequently named Alamgirnagar.[11] Maharaja Pran Narayan regained his kingdom within a few days.

British Raj

In 1772–1773, the king of Bhutan attacked and captured Cooch Behar. To expel the Bhutanese, the kingdom of Cooch Behar signed a defence treaty with the British East India Company on 5 April 1773. After expelling the Bhutanese, Cooch Behar again became a princely kingdom under the protection of British East India company.[12][13]

Cooch Behar Palace is built after the indo-saracenic architecture, the dome of the Palace is in Italian style, resembling the dome of St. Petersburg Cathedral, Vatican City, Rome and built in 1887, during the reign of Maharaja Nripendra Narayan.[11] In 1878, the maharaja married the daughter of Brahmo preacher Keshab Chandra Sen. This union led to a renaissance in Cooch Behar state.[14] Maharaja Nripendra Narayan is known as the architect of modern Cooch Behar town.[15]

Post-Independence

Under an agreement between the king of Cooch Behar and the Indian Government at the end of British rule, Maharaja Jagaddipendra Narayan transferred full authority, jurisdiction and power of the state to the Dominion Government of India, effective 12 September 1949.[6] Eventually, Cooch Bihar became part of the state of West Bengal on 19 January 1950, with Cooch Behar town as its headquarters.[6]

A geopolitical curiosity was that there were 92 Bangladeshi enclaves, with a total area of 47.7 km2 (18.4 sq mi) in Cooch-Behar. Similarly, there were 106 Indian enclaves inside Bangladesh, with a total area of 69.5 km2 (26.8 sq mi). These were part of the high stake card or chess games centuries ago between two regional kings, the Raja of Cooch Behar and the Maharaja of Rangpur.[16]

Twenty-one of the Bangladeshi enclaves were within Indian enclaves, and three of the Indian enclaves were within Bangladeshi enclaves. The largest Indian enclave was Balapara Khagrabari which surrounded a Bangladeshi enclave, Upanchowki Bhajni, which itself surrounded an Indian enclave called Dahala Khagrabari, of less than one hectare (link to external map here ). But all this has ended in the historic India-Bangladesh land agreement. See Indo-Bangladesh enclaves.

Geography

Cooch Behar is in the foothills of Eastern Himalayas, at 26°22′N 89°29′E in the north of West Bengal. It is the largest town and district headquarters of Cooch Behar District with an area of 8.29 km2 (3.20 sq mi).[17]

The elevation of the town is 48 meters above mean sea level.

The Torsa river flows by the western side of town. Heavy rains often cause strong river currents and flooding. The turbulent water carries huge amounts of sand, silt, and pebbles, which have an adverse effect on crop production as well as on the hydrology of the region.[18] Alluvial deposits form the soil, which is acidic.[18] Soil depth varies from 15 to 50 cm (5.9 to 19.7 in), superimposed on a bed of sand. The foundation materials are igneous and metamorphic rocks at a depth 1,000 to 1,500 m (3,300 to 4,900 ft). The soil has low levels of nitrogen with moderate levels of potassium and phosphorus. Deficiencies of boron, zinc, calcium, magnesium, and sulphur are high.[18]

Cooch Behar is a flat region with a slight southeastern slope along which the main rivers of the district flow. Most of the highland areas are in the Sitalkuchi region and most of the low-lying lands lie in Dinhata region.

The rivers in the district of Cooch Behar generally flow from northwest to southeast. Six rivers that cut through the district are the Teesta, Jaldhaka, Torsha, Kaljani, Raidak, Gadadhar and Ghargharia.

The town of Cooch Behar and its surrounding regions face deforestation due to increasing demand for fuel and timber, as well as air pollution from increasing vehicular traffic. The local flora include palms, bamboos, creepers, ferns, orchids, aquatic plants, fungi, timber, grass, vegetables, and fruit trees. Migratory birds, along with many local species, are found in the city, especially around the Sagardighi and other water bodies.[19]

In 1976 Cooch Behar district became home to the Jaldapara Wildlife Sanctuary (now Jaldapara National Park), which has an area of 217 km2 (83.8 sq mi).[20] It shares the park with Alipurduar district.[20]

.jpg.webp)

Climate

| Cooch Behar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Five distinct seasons (summer, monsoons, autumn, winter and spring) can be observed in Cooch Behar, of which summer, monsoons and winter are more prominent. Cooch Behar has a moderate climate characterised by heavy rainfall during the monsoons and slight rainfall from October to mid-November.[18] The district does not have high temperatures at any time of the year. The summer season is from April, the hottest month, to May. During the summer season, the mean daily maximum temperature is 36.5 °C (97.7 °F), and the mean daily minimum is 20.2 °C (68.4 °F).[21] The winter season lasts from the end of November to February; January is the coldest, when temperature ranges between 10.4 and 24.1 °C (50.7 and 75.4 °F).[21] The highest temperature in Cooch Behar was 41.0 °C, recorded on 11 September 1977; the lowest temperature recorded was 3.3 °C, reported on 28 January 1982 (see the weather box below). The atmosphere is highly humid except from February to March, when relative humidity is around 60 percent. The rainy season lasts from June to September. Average annual rainfall in the district is 3,248 mm (127.9 in).[21] However, the climate has undergone a drastic change in the past few years, with the mercury rising and the rainfall decreasing each year.[22]

| Climate data for Cooch Behar Airport (1981–2010, extremes 1901–2012) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 29.6 (85.3) |

31.5 (88.7) |

37.6 (99.7) |

39.4 (102.9) |

39.9 (103.8) |

40.3 (104.5) |

38.9 (102.0) |

38.0 (100.4) |

41.0 (105.8) |

36.1 (97.0) |

33.0 (91.4) |

33.4 (92.1) |

41.0 (105.8) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 23.4 (74.1) |

25.8 (78.4) |

29.6 (85.3) |

30.9 (87.6) |

31.2 (88.2) |

31.6 (88.9) |

31.2 (88.2) |

32.2 (90.0) |

31.2 (88.2) |

30.8 (87.4) |

28.7 (83.7) |

25.6 (78.1) |

29.3 (84.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 9.4 (48.9) |

11.9 (53.4) |

16.1 (61.0) |

19.9 (67.8) |

22.2 (72.0) |

24.1 (75.4) |

24.7 (76.5) |

25.0 (77.0) |

23.9 (75.0) |

20.8 (69.4) |

15.3 (59.5) |

11.0 (51.8) |

18.7 (65.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 3.3 (37.9) |

3.6 (38.5) |

7.1 (44.8) |

10.4 (50.7) |

16.1 (61.0) |

18.2 (64.8) |

20.3 (68.5) |

20.0 (68.0) |

19.7 (67.5) |

13.9 (57.0) |

8.2 (46.8) |

3.9 (39.0) |

3.3 (37.9) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 11.7 (0.46) |

18.5 (0.73) |

45.1 (1.78) |

167.6 (6.60) |

380.0 (14.96) |

683.3 (26.90) |

932.7 (36.72) |

618.2 (24.34) |

521.6 (20.54) |

164.6 (6.48) |

12.2 (0.48) |

7.1 (0.28) |

3,562.6 (140.26) |

| Average rainy days | 0.8 | 1.4 | 2.5 | 8.6 | 14.0 | 18.0 | 21.2 | 16.6 | 15.4 | 5.8 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 105.7 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 17:30 IST) | 70 | 60 | 53 | 62 | 71 | 78 | 81 | 80 | 83 | 79 | 73 | 72 | 72 |

| Source: India Meteorological Department[23][24] | |||||||||||||

Economy

The central and state governments are the small number of employers in Cooch Behar town. Cooch Behar is home to a number of district-level and divisional-level offices and has a large government-employee workforce. Business is mainly centred on retail goods; the main centres lie on B.S. Road, Rupnarayan Road, Keshab Road and at Bhawaniganj Bazar.

An industrial park has been built at Chakchaka, 4 km (2.5 mi) from town, on the route to Tufanganj. A number of small companies have set up industries there.[25]

Farming is a major source of livelihood for the nearby rural populace, and it supplies the town with fruits and vegetables. Poorer sections of this semi-rural society are involved in transport, basic agriculture, small shops, and manual labour in construction.

Cooch Behar has been witnessing radical changes, along with rapid development in segments like industry, real estate, and information technology firms, and education, since the advent of the twenty-first century. The changes are with respect to infrastructure and industrial growth for steel (direct reduced iron), metal, cement and knowledge-based industries. Many engineering, technology, management, and professional study colleges have opened at Cooch Behar. Housing co-operatives and flats, shopping malls, hotels and stadiums have also come up.

As the town is near the international border, the Border Security Force (BSF) maintains a large presence in the vicinity. This gives rise to a large population of semi-permanent residents, who bring revenue to the economy. The state government is trying to promote Cooch Behar as a tourist destination. Though income from tourism is low[26] Cooch Behar is one of the major tourist attractions in West Bengal.

Civic administration

Cooch Behar Municipality is responsible for the civic administration of the town. The municipality consists of a board of councillors, elected from each of the 20 wards[27] and a few members nominated by the state government. The board of councillors elects a chairman from among its elected members; the chairman is the executive head of the municipality. The All India Trinamool Congress holds power in the municipality. The state government looks after education, health and tourism.

The town is in the Cooch Behar constituency and elects one member to the Lok Sabha (the Lower House of the Indian Parliament). The town area is covered by one assembly constituency, Cooch Behar Dakshin, that elects one member to the Vidhan Sabha, which is the West Bengal state legislative assembly.[28] Cooch Behar town comes under the jurisdiction of the district police (which is a part of the state police); the Superintendent of Police oversees security and matters pertaining to law and order.

Cooch Behar is home to the District Court.

Utility services

Cooch Behar is a well-planned town,[29] and the municipality is responsible for providing basic services, such as potable water and sanitation. The water is supplied by the municipality using its groundwater resources, and almost all the houses in the municipal area are connected. Solid waste is collected every day by the municipality van from individual houses. The surface drains, mostly cemented, drain into the Torsa River. Electricity is supplied by the West Bengal State Electricity Board, and the West Bengal Fire Service provides emergency services like fire tenders. Most of the roads are metalled (macadam), and street lighting is available throughout the town. The Public Works Department is responsible for road maintenance and on the roads connecting Cooch Behar with other towns in the region. Health services in Cooch Behar include a government-owned District Hospital, a Regional Cancer Centre, and private nursing homes. Utility services provided in Cooch Behar is considered as one of the best government utility services of West Bengal though the city gets totally flooded during heavy rains nowadays due to the problems of the drainage system.

Health facilities

The city has one district hospital MJN Hospital which has 400 beds. The hospital has now been converted to Coochbehar Government Medical College and Hospital.[30]

Educational facilities

The city contains Cooch Behar Panchanan Barma University, seventeen high schools, forty-one primary schools and four colleges including Acharya Brojendra Nath Seal College, one polytechnic and one ITI college. Cooch Behar Government Engineering College began teaching in 2016.[31]

Market facilities

In the municipality are four daily markets, two wholesale markets and eight commercial complexes.[32]

Transport

Rickshaws, auto rickshaws and Totos are the most widely available public transport in Cooch Behar town. Most of Cooch Behar's residents stay within a few kilometres of the town centre and have their own vehicles, mostly motorcycles and bicycles.

The New Cooch Behar railway station is around 5 km from town and is well connected to almost all major Indian cities including Kolkata, Delhi, Mumbai, Bangalore, Chennai, Guwahati. All express and Superfast trains going towards North East have a stoppage here. The station came up in 1966 when Assam link was constructed through North Bengal. Now this station lies on New Jalpaiguri–New Bongaigaon section of Barauni-Guwahati line. As of 2018, it is the largest Railway Junction of Northeast Frontier Railway with six routes towards New Changrabandha, New Jalpaiguri, New Bongaigaon, Alipurduar Junction, Dhubri and Bamanhat. New Cooch Behar railway station is given a beautiful look similar to Cooch Behar Palace.

Another station named Cooch Behar situated inside the town exists but only few pairs of local trains run on this route. This station was built in 1901 when Cooch Behar State Railway constructed Geetaldaha-Jainti line. Now this station is operational due to local train services to Bamanhat. A Railway Museum is constructed in the station area having a look of Cooch Behar Madan Mohan Temple.

Cooch Behar is very well connected by road with neighbouring areas and other cities of West Bengal and rest of the country. Cooch Behar is a major roadway junction after Siliguri towards Northeast India and Bangladesh. Cooch Behar is headquarters of the North Bengal State Transport Corporation, which runs regular bus service to places in West Bengal, Assam and Bihar. Private buses are also available. Most buses depart from the Central Bus Terminus near Cooch Behar Rajbari. Hired vehicles are available from the taxi stand near Transport Chowpathi. City buses and autos serve inside and outskirts of the city.

The Cooch Behar Airport has modern passenger facilities but no airlines operate here. Steps are being taken to resume flights.[33]

The nearest airport is Bagdogra Airport near Siliguri, about 160 km (99 mi) from Cooch Behar. IndiGo and Spice Jet are the major carriers that connect the area to Delhi, Kolkata, Guwahati, Mumbai, Chennai, Bangkok, Paro and Chandigarh.

Demographics

In the 2011 census, Cooch Behar Urban Agglomeration had a population of 106,760, out of which 53,803 were males and 52,957 were females. The 0–6 years population was 7,910. Effective literacy rate for the over 7 population was 91.75%.[34]

As per the 2001 census,[35] the Cooch Behar municipal area has a population of 76,812. The sex ratio is 972 females per 1,000 males. The decadal growth rate for the population is 7.86%. Males constitute 50.6% of the population, and females constitute 49.4%. Cooch Behar has an average literacy rate of 82%, which is higher than the national average of 64.84%. The male literacy rate is 86%, while female literacy rate is 77%. In Cooch Behar, 9% of the population is under 6 years of age.[17]

The major religions followed in Cooch Behar are Hinduism (76.44%) followed by Islam (23.34%).[21] Commonly spoken languages are Bengali and Kamtapuri.[21][36]

Culture

Every year during the Ras Purnima, the city hosts Ras Mela, one of the largest and oldest fairs of West Bengal. The fair is older than 200 years. The fair is organised by Cooch Behar Municipality in the Ras Mela ground near ABN Seal College. During the fair, it becomes a major economical hub of the whole North Bengal region. Merchants and sellers from all over India and also from Bangladesh join this fair. Earlier the Maharajas of Cooch Behar used to inaugurate the fair by moving the Ras Chakra and now the work is executed by the District Magistrate of Cooch Behar District. The Ras Chakra is considered as a symbol of communal harmony because it is made by a Muslim Family from generations.A huge crowd gather in Cooch Behar from neighbouring Assam, Jalpaiguri, Alipurduar and whole North Bengal during the fair.

Novelist Amiya Bhushan Majumdar was born, brought up, and worked in Cooch Behar. Cooch Behar with its people, culture, and the river Torsha were a recurrent theme in his novels.

Education

Cooch Behar's schools usually use English and Bengali as their medium of instruction, although the use of Hindi language is also stressed. The schools are affiliated with the Indian Certificate of Secondary Education (ICSE) or the Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE) or the West Bengal Board of Secondary Education. Some of the reputed schools include Jenkins School, Sunity Academy and Cooch Behar Rambhola High School.

Cooch Behar Panchanan Barma University is the only single university in Cooch Behar. it is a U.G.C. recognised public university in Cooch Behar, West Bengal, India. The university was named after the 19th-century Rajbongshi leader and social reformist, Panchanan Barma. A total of 15 colleges from Cooch Behar district are affiliated to the university.[37]

There are five colleges and a polytechnic in town[38] including A.B.N. Seal College, Cooch Behar College, University B.T. & Evening College, Thakur Panchanan Mahila Mahavidyalaya all of which are affiliated with the Cooch Behar Panchanan Barma University, which was established in 2013.[39][40] Cooch Behar Polytechnic, a government diploma-level institute with 3 yrs. (10+) Civil, Electrical, Mechanical & Automobile Engineering and 2 yrs. (12+) Pharmacy course under West Bengal State Council of Technical Education, Kolkata.

Acharya Brojendra Nath Seal College was established in 1888 as Victoria College by Maharaja Nripendra Narayan of Koch Bihar to enhance student capability in the Kingdom. The first principal was John Cornwallis Godley who in 1895 became the second principal of Aitchison College in Lahore. Later Maharaja Nripendra Naryayan offered the post of principal to Acharya Brojendra Nath Seal, a Brahmo and philosopher, who remained in the post for eighteen years from 1896 to 1913. In 1950, when the state of Cooch Behar was merged into Union of India, the governance was passed to Government of West Bengal. It was earlier affiliated to the University of Calcutta and University of North Bengal and is now affiliated to Cooch Behar Panchanan Barma University after the creation of the same. In 1970, it was renamed as Acharya Brojendra Nath Seal College. It is one of the few colleges under the Cooch Behar Panchanan Barma University to give postgraduate education. The college is in the heart of the town with a campus of 13.27 acres (53,700 m2) and built-up area of 9032.96 sq. meters.[41]

There is an agricultural university, Uttar Banga Krishi Vishwavidyalaya, just outside the main town at Pundibari. A medical college is proposed to be opened by the Government at Raja Jagatdipendranarayan TB Hospital.[42]

Cooch Behar Government Engineering College started its first academic session in 2016.[43]

Tourism

Cooch Behar is one of the major tourist places of West Bengal. The main attractions are:

Cooch Behar Palace

It is the main attraction of the city. It was modelled after the Buckingham Palace in London in 1887, during the reign of Maharaja Nripendra Narayan. It is a brick-built double-story structure in the classical Western style covering an area of 51,309 square feet (4,766.8 m2). The whole structure is 395 feet (120 m) long and 296 feet (90 m) wide and is on rests 4 feet 9 inches (1.45 m) above the ground. The Palace is fronted on the ground and first floors by a series of arcaded verandahs with their piers arranged alternately in single and double rows. At the southern and northern ends, the Palace projects slightly and in the centre is a projected porch providing an entrance to the Durbar Hall. The Hall has an elegantly shaped metal dome which is topped by a cylindrical louvre type ventilator. This is 124 feet (38 m) high from the ground and is in the style of the Renaissance architecture. The intros of the dome is carved in stepped patterns and Corinthian columns support the base of the cupola. This adds variegated colours and designs to the entire surface. There are various halls in the palace and rooms that include the Dressing Room, Bed Room, Drawing Room, Dining Hall, Billiard hall, Library, Toshakhana, Ladies Gallery and Vestibules. The articles and precious objects that these rooms and halls used to contain are now lost. The original palace was 3 storeyed, but, was subsequently destroyed by a 19th-century earthquake measuring 8.7 on Richter scale. The palace shows the acceptance of European idealism of the Koch kings and the fact that they had embraced European culture without denouncing their Indian heritage.[44]

Sagar Dighi

Sagardighi is one of "Great Ponds" in the heart of Cooch Behar, West Bengal. The name means an ocean-like pond, exaggerated in view of its great significance. As well as being popular with people, it also attracts migratory birds each winter. It is surrounded by many important administrative buildings, like District Magistrates Office, Administrative Building of North Bengal State Transport Corporation, BSNL's DTO Office on the West; Office of the Superintendent of Police, District Library, Municipality Building on the South, Office of BLRO, State Bank of India's Cooch Behar Main Branch and many other on the East and RTO office, Foreigner's registration office, District Court etc. on the North. Most of such buildings are remnants of royal heritage.[45]

Gallery

Indoor Stadium, cooch Behar

Indoor Stadium, cooch Behar District Court

District Court ABN Seal College

ABN Seal College Cooch Behar Airport

Cooch Behar Airport Railway Museum near Cooch Behar Station

Railway Museum near Cooch Behar Station Palace Gate

Palace Gate.jpg.webp) Sahid Bag, Cooch Behar

Sahid Bag, Cooch Behar.jpg.webp) Bhola Ashram, Cooch Behar

Bhola Ashram, Cooch Behar.jpg.webp) Madan Mohan Bari Entrance

Madan Mohan Bari Entrance.jpg.webp) Circuit House

Circuit House New Cooch Behar at night

New Cooch Behar at night New Cooch Behar Junction

New Cooch Behar Junction.jpg.webp) Debi Bari Cooch Behar

Debi Bari Cooch Behar.jpg.webp) Moti Mahal

Moti Mahal Madanmohan Temple at night

Madanmohan Temple at night.jpg.webp) Palace view from stadium

Palace view from stadium

See also

- Narendra Narayan Park, a botanical garden in town, founded in 1892

- Cooch Behar Stadium, a multi-purpose stadium

References

- "Cooch Behar City". coochbeharmunicipality.com. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- "Fact and Figures". www.wb.gov.in. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- "52nd Report of the Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities in India" (PDF). nclm.nic.in. Ministry of Minority Affairs. p. 85. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- Coochbehar Travel. Mytourideas.com. Retrieved on 18 July 2015.

- The Tribune, Chandigarh, India – Nation. Tribuneindia.com. 23 June 2001.

- "Brief Royal History of Cooch Behar 5". Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 22 October 2006.

- Pal, Dr. Nripendra Nath (2000). Itikathai Cooch Behar (A brief history of Cooch Behar). Kolkata: Anima Prakashani. pp. 11–12.

- Royal history of Cooch Behar. Coochbehar.nic.in (1 January 1950). Retrieved on 18 July 2015.

- "Royal History of Cooch Behar". Retrieved 22 October 2006.

- Pal, Dr. Nripendra Nath (2000). Itikathai Cooch Behar (A brief history of Cooch Behar). Kolkata: Anima Prakashani. p. 68.

- Bhattacharyya, PK (2012). "Kamata-Koch Behar". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- Pal, Dr. Nripendra Nath (2000). Itikathai Cooch Behar (A brief history of Cooch Behar). Kolkata: Anima Prakashani. p. 73.

- Bowman, John S., ed. (2000). Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 385. ISBN 0-231-11004-9.

- Pal, Dr. Nripendra Nath (2000). Itikathai Cooch Behar (A brief history of Cooch Behar). Kolkata: Anima Prakashani. p. 75.

- "Royal History of Cooch Behar 5". Retrieved 22 October 2006.

- "A Great Divide". Time. 5 February 2009.

- "West Bengal Census". Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 1 October 2006.

- Annual Plan on Agriculture 2003–04. Cooch Behar: Cooch Behar District Agriculture Office. p. 2.

- "West Bengal Tourism: Cooch Behar". Archived from the original on 15 July 2009.

- Indian Ministry of Forests and Environment. "Protected areas: Sikkim". Archived from the original on 23 August 2011. Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- District Profile, Cooch Behar Government website Archived 15 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine Accessed on 1 October 2006

- Sharma Lakhotia, Anuradha (7 November 2006). "Darjeeling warming up faster than earth". The Telegraph. Retrieved 7 November 2006.

- "Station: Cooch Behar (A) Climatological Table 1981–2010" (PDF). Climatological Normals 1981–2010. India Meteorological Department. January 2015. pp. 207–208. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- "Extremes of Temperature & Rainfall for Indian Stations (Up to 2012)" (PDF). India Meteorological Department. December 2016. p. M233. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- Industries in Cooch Behar, Cooch Behar Government Website Archived 15 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine Accessed on 1 October 2006

- Tourism Development in Cooch Behar, Cooch Behar Government Website Archived 15 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine Accessed on 1 October 2006

- District Administration Accessed on 1 October 2006

- "Press Note, Delimitation Commission" (PDF). Assembly Constituencies in West Bengal. Delimitation Commission. pp. 4, 23. Retrieved 18 April 2009.

- "North Bengal: Cooch Behar". Archived from the original on 8 November 2006. Retrieved 7 November 2006.

- "Rush to start Cooch Behar medical college". Archived from the original on 9 September 2019. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- "COOCHBEHAR GOVERNMENT ENGINEERING COLLEGE, COOCH BEHAR". Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- "Social Infrastructure". Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- "More airports for Indian cities, says India's Civil Aviation Minister". Trav Talk. 27 March 2006. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 29 September 2006.

- "Urban Agglomerations/Cities having population 100,000 and above" (PDF). Provisional Population Totals, Census of India 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- "Census of India 2001: Data from the 2001 Census, including cities, villages and towns (Provisional)". Census Commission of India. Archived from the original on 16 June 2004. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- "Rangpuri | Ethnologue". ethnologue.com. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- "Coochbehar Panchanan Barma University :: Home".

- Education in Cooch Behar, Cooch Behar Government Website Archived 15 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine Accessed on 1 October 2006

- "Private education Bill passed amidst Opposition walkout". The Statesman. 6 July 2012. Archived from the original on 20 December 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- "Bill passed to set up private varsity". Asian Age. 7 July 2012. Archived from the original on 11 December 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- "Acharya Brojendra Nath Seal College". Archived from the original on 9 September 2019. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- Ganguly, Arnab (12 July 2012). "Medical college for Cooch Behar". The Telegraph. Retrieved 27 October 2012.

- EOI, Correspondence. "NBDD minister inaugurates multiple projects in Cooch Behar". Archived from the original on 14 January 2015.

- "Rajbari in Cooch Behar town".

- "Tourist places of Cooch Behar".

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cooch Behar. |

![]() Cooch Behar travel guide from Wikivoyage

Cooch Behar travel guide from Wikivoyage