Cyrillic alphabets

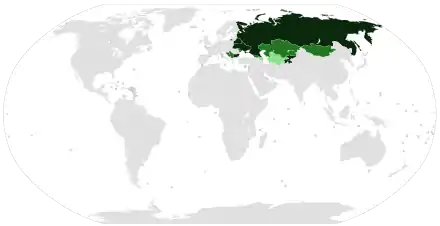

Numerous Cyrillic alphabets are based on the Cyrillic script. The early Cyrillic alphabet was developed in the First Bulgarian Empire during the 9th century AD (in all probability in Ravna Monastery) at the Preslav Literary School by Saint Clement of Ohrid and Saint Naum and replaced the earlier Glagolitic script developed by the Byzantine theologians Cyril and Methodius (in all probability in Polychron). It is the basis of alphabets used in various languages, past and present, in parts of Southeastern Europe and Northern Eurasia, especially those of Slavic origin, and non-Slavic languages influenced by Russian. As of 2011, around 252 million people in Eurasia use it as the official alphabet for their national languages. About half of them are in Russia. Cyrillic is one of the most-used writing systems in the world.

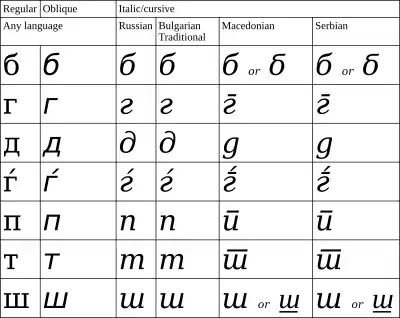

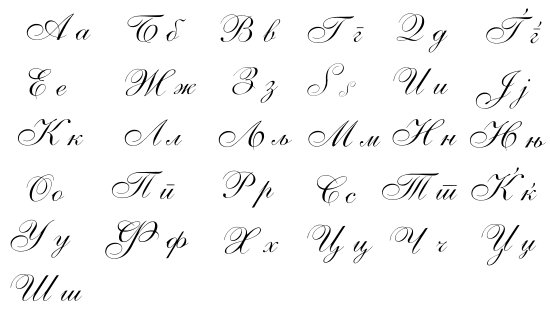

Some of these are illustrated below; for others, and for more detail, see the links. Sounds are transcribed in the IPA. While these languages by and large have phonemic orthographies, there are occasional exceptions—for example, Russian ⟨г⟩ is pronounced /v/ in a number of words, an orthographic relic from when they were pronounced /ɡ/ (e.g. его yego 'him/his', is pronounced [jɪˈvo] rather than [jɪˈɡo]).

Spellings of names transliterated into the Roman alphabet may vary, especially й (y/j/i), but also г (gh/g/h) and ж (zh/j).

Non-Slavic alphabets are generally modelled after Russian, but often bear striking differences, particularly when adapted for Caucasian languages. The first few of these alphabets were developed by Orthodox missionaries for the Finnic and Turkic peoples of Idel-Ural (Mari, Udmurt, Mordva, Chuvash, and Kerashen Tatars) in the 1870s. Later, such alphabets were created for some of the Siberian and Caucasus peoples who had recently converted to Christianity. In the 1930s, some of those languages were switched to the Uniform Turkic Alphabet. All of the peoples of the former Soviet Union who had been using an Arabic or other Asian script (Mongolian script etc.) also adopted Cyrillic alphabets, and during the Great Purge in the late 1930s, all of the Latin alphabets of the peoples of the Soviet Union were switched to Cyrillic as well (the Baltic Republics were annexed later, and were not affected by this change). The Abkhazian and Ossetian languages were switched to Georgian script, but after the death of Joseph Stalin, both also adopted Cyrillic. The last language to adopt Cyrillic was the Gagauz language, which had used Greek script before.

In Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan, the use of Cyrillic to write local languages has often been a politically controversial issue since the collapse of the Soviet Union, as it evokes the era of Soviet rule and Russification. Some of Russia's peoples such as the Tatars have also tried to drop Cyrillic, but the move was halted under Russian law. A number of languages have switched from Cyrillic to other orthographies—either Roman‐based or returning to a former script.

Unlike the Latin script, which is usually adapted to different languages by adding diacritical marks/supplementary glyphs (such as accents, umlauts, fadas, tildes and cedillas) to standard Roman letters, by assigning new phonetic values to existing letters (e.g. <c>, whose original value in Latin was /k/, represents /ts/ in West Slavic languages, /ʕ/ in Somali, /t͡ʃ/ in many African languages and /d͡ʒ/ in Turkish), or by the use of digraphs (such as <sh>, <ch>, <ng> and <ny>), the Cyrillic script is usually adapted by the creation of entirely new letter shapes. However, in some alphabets invented in the 19th century, such as Mari, Udmurt and Chuvash, umlauts and breves also were used.

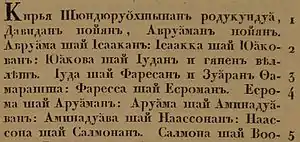

Bulgarian and Bosnian Sephardim without Hebrew typefaces occasionally printed Judeo-Spanish in Cyrillic.[1]

Common letters

The following table lists the Cyrillic letters which are used in the alphabets of most of the national languages which use a Cyrillic alphabet. Exceptions and additions for particular languages are noted below.

| Upright | Italic/Cursive | Name | Sound (in IPA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| А а | А а | A | /a/ |

| Б б | Б б | Be | /b/ |

| В в | В в | Ve | /v/ |

| Г г | Г г | Ge | /ɡ/ |

| Д д | Д д | De | /d/ |

| Е е | Е е | E | /je/, /ʲe/ |

| Ж ж | Ж ж | Zhe | /ʒ/ |

| З з | З з | Ze | /z/ |

| И и | И и | I | /i/, /ʲi/ |

| Й й | Й й | Short I[lower-alpha 1] | /j/ |

| К к | К к | Ka | /k/ |

| Л л | Л л | El | /l/ |

| М м | М м | Em | /m/ |

| Н н | Н н | En/Ne | /n/ |

| О о | О о | O | /o/ |

| П п | П п | Pe | /p/ |

| Р р | Р р | Er/Re | /r/ |

| С с | С с | Es | /s/ |

| Т т | Т т | Te | /t/ |

| У у | У у | U | /u/ |

| Ф ф | Ф ф | Ef/Fe | /f/ |

| Х х | Х х | Kha | /x/ |

| Ц ц | Ц ц | Tse | /ts/ (t͡s) |

| Ч ч | Ч ч | Che | /tʃ/ (t͡ʃ) |

| Ш ш | Ш ш | Sha | /ʃ/ |

| Щ щ | Щ щ | Shcha, Shta | /ʃtʃ/, /ɕː/, /ʃt/[lower-alpha 2] |

| Ь ь | Ь ь | Soft sign[lower-alpha 3] or Small yer[lower-alpha 4] |

/ʲ/[lower-alpha 5] |

| Ю ю | Ю ю | Yu | /ju/, /ʲu/ |

| Я я | Я я | Ya | /ja/, /ʲa/ |

- Russian: и краткое, i kratkoye; Bulgarian: и кратко, i kratko. Both mean "Short i".

- See the notes for each language for details

- Russian: мягкий знак, myagkiy znak

- Bulgarian: ер малък, er malâk

- The soft sign ⟨ь⟩ usually does not represent a sound, but modifies the sound of the preceding letter, indicating palatalization ("softening"), also separates the consonant and the following vowel. Sometimes it does not have phonetic meaning, just orthographic; e.g. Russian туш, tush [tuʂ] 'flourish after a toast'; тушь, tushʹ [tuʂ] 'India ink'. In some languages, a hard sign ⟨ъ⟩ or apostrophe ⟨’⟩ just separates the consonant and the following vowel (бя [bʲa], бья [bʲja], бъя = б’я [bja]).

Slavic languages

Cyrillic alphabets used by Slavic languages can be divided into two categories:

- East South Slavic languages and East Slavic languages, such as Bulgarian and Russian, share common features such as Й, ь, and я.

- West South Slavic languages, such as Serbian, share common features such as Ј and љ.

Russian

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з | И и | Й й |

| К к | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | П п | Р р | С с | Т т | У у | Ф ф |

| Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ы ы | Ь ь | Э э | Ю ю | Я я |

- Yo (Ё ё) /jo/

- The Hard Sign¹ (Ъ ъ) indicates no palatalization²

- Yery (Ы ы) indicates [ɨ] (an allophone of /i/)

- E (Э э) /e/

- Ж and Ш indicate sounds that are retroflex

Notes:

- In the pre-reform Russian orthography, in Old East Slavic and in Old Church Slavonic the letter is called yer. Historically, the "hard sign" takes the place of a now-absent vowel, which is still preserved as a distinct vowel in Bulgarian (which represents it with ъ) and Slovene (which is written in the Latin alphabet and writes it as e), but only in some places in the word.

- When an iotated vowel (vowel whose sound begins with [j]) follows a consonant, the consonant is palatalized. The Hard Sign indicates that this does not happen, and the [j] sound will appear only in front of the vowel. The Soft Sign indicates that the consonant should be palatalized in addition to a [j] preceding the vowel. The Soft Sign also indicates that a consonant before another consonant or at the end of a word is palatalized. Examples: та ([ta]); тя ([tʲa]); тья ([tʲja]); тъя ([tja]); т (/t/); ть ([tʲ]).

Before 1918, there were four extra letters in use: Іі (replaced by Ии), Ѳѳ (Фита "Fita", replaced by Фф), Ѣѣ (Ять "Yat", replaced by Ее), and Ѵѵ (ижица "Izhitsa", replaced by Ии); these were eliminated by reforms of Russian orthography.

Belarusian

The Belarusian alphabet

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з | І і | Й й |

| К к | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | П п | Р р | С с | Т т | У у | Ў ў |

| Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Ы ы | Ь ь | Э э | Ю ю | Я я | ’ |

The Belarusian alphabet displays the following features:

- Ge (Г г) represents a voiced velar fricative /ɣ/.

- Yo (Ё ё) /jo/

- I (І і), also known as the dotted I or decimal I, resembles the Latin letter I. Unlike Russian and Ukrainian, "И" is not used.

- Short I (Й й), however, uses the base И glyph.

- Short U (Ў ў) is the letter У with a breve and represents /w/, or like the u part of the diphthong in loud. The use of the breve to indicate a semivowel is analogous to the Short I (Й).

- A combination of Sh and Ch (ШЧ шч) is used where those familiar only with Russian and or Ukrainian would expect Shcha (Щ щ).

- Yery (Ы ы) /ɨ/

- E (Э э) /ɛ/

- An apostrophe (’) is used to indicate depalatalization of the preceding consonant. This orthographical symbol used instead of the traditional Cyrillic letter Yer (Ъ), also known as the hard sign.

- The letter combinations Dzh (Дж дж) and Dz (Дз дз) appear after D (Д д) in the Belarusian alphabet in some publications. These digraphs represent consonant clusters Дж /dʒ/ and Дз /dz/ correspondingly.

- Before 1933, the letter Ґ ґ was used.

Ukrainian

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Ґ ґ | Д д | Е е | Є є | Ж ж | З з | И и |

| І і | Ї ї | Й й | К к | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | П п | Р р | С с |

| Т т | У у | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ь ь | Ю ю | Я я |

The Ukrainian alphabet displays the following features:

- Ve (В) represents /ʋ/ (which may be pronounced [w] in a word final position and before consonants).

- He (Г, г) represents a voiced glottal fricative, (/ɦ/).

- Ge (Ґ, ґ) appears after He, represents /ɡ/. It looks like He with an "upturn" pointing up from the right side of the top bar. (This letter was not officially used in Soviet Ukraine in 1933—1990, so it may be missing from older Cyrillic fonts.)

- E (Е, е) represents /ɛ/.

- Ye (Є, є) appears after E, represents /jɛ/.

- E, И (И, и) represent /ɪ/ if unstressed.

- I (І, і) appears after Y, represents /i/.

- Yi (Ї, ї) appears after I, represents /ji/.

- Yy (Й, й) represents /j/.

- Shchy (Щ, щ) represents /ʃtʃ/.

- An apostrophe (’) is used to mark nonpalatalization of the preceding consonant before Ya (Я, я), Yu (Ю, ю), Ye (Є, є), Yi (Ї, ї).

- Like in Belarusian Cyrillic, the sounds /dʒ/, /dz/ are represented by digraphs Дж and Дз respectively.

- Until reforms in 1990, soft sign (Ь, ь) appeared at the end of the alphabet, after Yu (Ю, ю) and Ya (Я, я), rather than before them, as in Russian.

Rusyn

The Rusyn language is spoken by the Lemko Rusyns in Carpathian Ruthenia, Slovakia, and Poland, and the Pannonian Rusyns in Croatia and Serbia.

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Ґ ґ | Д д | Е е | Є є | Ё ё* | Ж ж | З з |

| И и | І і* | Ы ы* | Ї ї | Й й | К к | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | П п |

| Р р | С с | Т т | У у | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ѣ ѣ* |

| Ю ю | Я я | Ь ь | Ъ ъ* |

*Letters absent from Pannonian Rusyn alphabet.

Bulgarian

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ж ж | З з | И и | Й й |

| К к | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | П п | Р р | С с | Т т | У у |

| Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ь ь | Ю ю | Я я |

The Bulgarian alphabet features:

- The Bulgarian names for the consonants are [bɤ], [kɤ], [ɫɤ] etc. instead of [bɛ], [ka], [ɛl] etc.

- Е represents /ɛ/ and is called "е" [ɛ].

- The sounds /dʒ/ (/d͡ʒ/) and /dz/ (/d͡z/) are represented by дж and дз respectively.

- Yot (Й, й) represents /j/.

- Щ represents /ʃt/ (/ʃ͡t/) and is called "щъ" [ʃtɤ] ([ʃ͡tɤ]).

- Ъ represents the vowel /ɤ/, and is called "ер голям" [ˈɛr ɡoˈljam] ('big er'). In spelling however, Ъ is referred to as /ɤ/ where its official label "ер голям" (used only to refer to Ъ in the alphabet) may cause some confusion. The vowel Ъ /ɤ/ is sometimes approximated to the /ə/ (schwa) sound found in many languages for easier comprehension of its Bulgarian pronunciation for foreigners, but it is actually a back vowel, not a central vowel.

- Ь is used on rare occasions (only after a consonant [and] before the vowel "о"), such as in the words 'каньон' (canyon), 'шофьор' (driver), etc. It is called "ер малък" ('small er').

The Cyrillic alphabet was originally developed in the First Bulgarian Empire during the 9th – 10th century AD at the Preslav Literary School.[2][3]

It has been used in Bulgaria (with modifications and exclusion of certain archaic letters via spelling reforms) continuously since then, superseding the previously used Glagolitic alphabet, which was also invented and used there before the Cyrillic script overtook its use as a written script for the Bulgarian language. The Cyrillic alphabet was used in the then much bigger territory of Bulgaria (including most of today’s Serbia), North Macedonia, Kosovo, Albania, Northern Greece (Macedonia region), Romania and Moldova, officially from 893. It was also transferred from Bulgaria and adopted by the East Slavic languages in Kievan Rus' and evolved into the Russian alphabet and the alphabets of many other Slavic (and later non-Slavic) languages. Later, some Slavs modified it and added/excluded letters from it to better suit the needs of their own language varieties.

Serbian

South Slavic Cyrillic alphabets (with the exception of Bulgarian) are generally derived from Serbian Cyrillic. It, and by extension its descendants, differs from the East Slavic ones in that the alphabet has generally been simplified: Letters such as Я, Ю, and Ё, representing /ja/, /ju/, and /jo/ in Russian, respectively, have been removed. Instead, these are represented by the digraphs ⟨ја⟩, ⟨јu⟩, and ⟨јо⟩, respectively. Additionally, the letter Е, representing /je/ in Russian, is instead pronounced /e/ or /ɛ/, with /je/ being represented by ⟨јe⟩. Alphabets based on the Serbian that add new letters often do so by adding an acute accent ⟨´⟩ over an existing letter.

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Ђ ђ | Е е | Ж ж | З з | И и |

| Ј ј | К к | Л л | Љ љ | М м | Н н | Њ њ | О о | П п | Р р |

| С с | Т т | Ћ ћ | У у | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Џ џ | Ш ш |

The Serbian alphabet shows the following features:

- E represents /ɛ/.

- Between Д and E is the letter Dje (Ђ, ђ), which represents /dʑ/, and looks like Tshe, except that the loop of the h curls farther and dips downwards.

- Between И and К is the letter Je (Ј, ј), represents /j/, which looks like the Latin letter J.

- Between Л and М is the letter Lje (Љ, љ), representing /ʎ/, which looks like a ligature of Л and the Soft Sign.

- Between Н and О is the letter Nje (Њ, њ), representing /ɲ/, which looks like a ligature of Н and the Soft Sign.

- Between Т and У is the letter Tshe (Ћ, ћ), representing /tɕ/ and looks like a lowercase Latin letter h with a bar. On the uppercase letter, the bar appears at the top; on the lowercase letter, the bar crosses the top at half of the vertical line.

- Between Ч and Ш is the letter Dzhe (Џ, џ), representing /dʒ/, which looks like Tse but with the descender moved from the right side of the bottom bar to the middle of the bottom bar.

- Ш is the last letter.

- Certain letters are handwritten differently,[4] as seen in the adjacent image.

Macedonian

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Ѓ ѓ | Е е | Ж ж | З з | Ѕ ѕ | И и |

| Ј ј | К к | Л л | Љ љ | М м | Н н | Њ њ | О о | П п | Р р | С с |

| Т т | Ќ ќ | У у | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Џ џ | Ш ш |

The Macedonian alphabet differs from Serbian in the following ways:

- Between Ze (З з) and I (И и) is the letter Dze (Ѕ ѕ), which looks like the Latin letter S and represents /d͡z/.

- Dje (Ђ ђ) is replaced by Gje (Ѓ ѓ), which represents /ɟ/ (voiced palatal stop). In some dialects, it represents /d͡ʑ/ instead, like Dje. It is written ⟨Ǵ ǵ⟩ in the corresponding Macedonian Latin alphabet.

- Tshe (Ћ ћ) is replaced by Kje (Ќ ќ), which represents /c/ (voiceless palatal stop). In some dialects, it represents /t͡ɕ/ instead, like Tshe. It is written ⟨Ḱ ḱ⟩ in the corresponding Macedonian Latin alphabet.

- Lje (Љ љ) often represents the consonant cluster /lj/ instead of /ʎ/.

- Certain letters are handwritten differently, as seen in the adjacent image.[5]

Montenegrin

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Ђ ђ | Е е | Ж ж | З з | З́ з́ | И и |

| Ј ј | К к | Л л | Љ љ | М м | Н н | Њ њ | О о | П п | Р р | С с |

| С́ с́ | Т т | Ћ ћ | У у | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Џ џ | Ш ш |

The Montenegrin alphabet differs from Serbian in the following ways:

- Between Ze (З з) and I (И и) is the letter З́, which represents /ʑ/ (voiced alveolo-palatal fricative). It is written ⟨Ź ź⟩ in the corresponding Montenegrin Latin alphabet, previously written ⟨Zj zj⟩ or ⟨Žj žj⟩.

- Between Es (С с) and Te (Т т) is the letter С́, which represents /ɕ/ (voiceless alveolo-palatal fricative). It is written ⟨Ś ś⟩ in the corresponding Montenegrin Latin alphabet, previously written ⟨Sj sj⟩ or ⟨Šj šj⟩.

- The letter Dze (Ѕ ѕ), from Macedonian, is used in scientific literature when representing the /d͡z/ phoneme, although it is not officially part of the alphabet. A Latin equivalent was proposed that looks identical to Ze (З з).

Bosnian

The Bosnian language uses Latin and Cyrillic alphabets. Latin is slightly more common.[6] A Bosnian Cyrillic script (Bosančica) was used in the Middle Ages, along with other scripts Bosnian language.

Uralic languages

Uralic languages using the Cyrillic script (currently or in the past) include:

- Finnic: Karelian until 1921 and 1937–1940 (Ludic, Olonets Karelian); Veps; Votic

- Kildin Sami in Russia (since the 1980s)

- Komi (Zyrian (since the 17th century, modern alphabet since the 1930s); Permyak; Yodzyak)

- Udmurt

- Khanty

- Mansi (writing has not received distribution since 1937)

- Samoyedic: Enets; Yurats; Nenets since 1937 (Forest Nenets; Tundra Nenets); Nganasan; Kamassian; Koibal; Mator; Selkup (since the 1950s; not used recently)

- Mari, since the 19th century (Hill; Meadow)

- Mordvin, since the 18th century (Erzya; Moksha)

- Other: Merya; Muromian; Meshcherian

Karelian

The Karelian language was written in the Cyrillic script in various forms until 1940 when publication in Karelian ceased in favor of Finnish, except for Tver Karelian, written in a Latin alphabet. In 1989 publication began again in the other Karelian dialects and Latin alphabets were used, in some cases with the addition of Cyrillic letters such as ь.

Kildin Sámi

Over the last century, the alphabet used to write Kildin Sami has changed three times: from Cyrillic to Latin and back again to Cyrillic. Work on the latest version of the official orthography commenced in 1979. It was officially approved in 1982 and started to be widely used by 1987.[7]

Komi-Permyak

The Komi-Permyak alphabet:

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё |

| Ж ж | З з | И и | I i | Й й | К к | Л л |

| М м | Н н | О о | Ӧ ӧ | П п | Р р | С с |

| Т т | У у | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш |

| Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ы ы | Ь ь | Э э | Ю ю | Я я |

Mari alphabets

Meadow Mari alphabet:

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з | И и |

| Й й | К к | Л л | М м | Н н | Ҥ ҥ | О о | Ö ö | П п | Р р |

| С с | Т т | У у | Ӱ ӱ | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ |

| Ъ ъ | Ы ы | Ь ь | Э э | Ю ю | Я я |

Hill Mari alphabet

| А а | Ä ä | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з |

| И и | Й й | К к | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | Ö ö | П п | Р р |

| С с | Т т | У у | Ӱ ӱ | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ |

| Ъ ъ | Ы ы | Ӹ ӹ | Ь ь | Э э | Ю ю | Я я |

Non-Slavic Indo-European languages

Kurdish

Kurds in the former Soviet Union use a Cyrillic alphabet:

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Г' г' | Д д | Е е | Ә ә |

| Ә' ә' | Ж ж | З з | И и | Й й | К к | К' к' | Л л |

| М м | Н н | О о | Ö ö | П п | П' п' | Р р | Р' р' |

| С с | Т т | Т' т' | У у | Ф ф | Х х | Һ һ | Һ' һ' |

| Ч ч | Ч' ч' | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ь ь | Э э | Ԛ ԛ | Ԝ ԝ |

Ossetian

The Ossetic language has officially used the Cyrillic script since 1937.

| А а | Ӕ ӕ | Б б | В в | Г г | Гъ гъ | Д д | Дж дж |

| Дз дз | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з | И и | Й й | К к |

| Къ къ | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | П п | Пъ пъ | Р р |

| С с | Т т | Тъ тъ | У у | Ф ф | Х х | Хъ хъ | Ц ц |

| Цъ цъ | Ч ч | Чъ чъ | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ы ы | Ь ь |

| Э э | Ю ю | Я я |

Tajik

The Tajik language is written using a Cyrillic-based alphabet.

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Ғ ғ | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з | И и | |

| Ӣ ӣ | Й й | К к | Қ қ | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | П п | Р р | С с | |

| Т т | У у | Ӯ ӯ | Ф ф | Х х | Ҳ ҳ | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ҷ ҷ | Ш ш | Ъ ъ | |

| Э э | Ю ю | Я я |

Romance languages

- Romanian (up to the 19th century; see Romanian Cyrillic alphabet).

- The Moldovan language (an alternative name of the Romanian language in Bessarabia, Moldavian ASSR, Moldavian SSR and Moldova) used varieties of the Romanian Cyrillic alphabet in 1812–1918, and the Moldovan Cyrillic alphabet (derived from the Russian alphabet and standardised in the Soviet Union) in 1924–1932 and 1938–1989. Nowadays, this alphabet is still official in the unrecognized republic of Transnistria (see Moldovan Cyrillic alphabet).

- Ladino in occasional Bulgarian Sephardic publications.

Romani

Romani is written in Cyrillic in Serbia, Montenegro, Bulgaria and the former USSR.

Mongolian

The Mongolic languages include Khalkha (in Mongolia), Buryat (around Lake Baikal) and Kalmyk (northwest of the Caspian Sea). Khalkha Mongolian is also written with the Mongol vertical alphabet.

Overview

This table contains all the characters used.

Һһ is shown twice as it appears at two different locations in Buryat and Kalmyk

| Khalkha | Аа | Бб | Вв | Гг | Дд | Ее | Ёё | Жж | Зз | Ии | Йй | Кк | Лл | Мм | Нн | Оо | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buryat | Аа | Бб | Вв | Гг | Дд | Ее | Ёё | Жж | Зз | Ии | Йй | Лл | Мм | Нн | Оо | |||||

| Kalmyk | Аа | Әә | Бб | Вв | Гг | Һһ | Дд | Ее | Жж | Җҗ | Зз | Ии | Йй | Кк | Лл | Мм | Нн | Ңң | Оо | |

| Khalkha | Өө | Пп | Рр | Сс | Тт | Уу | Үү | Фф | Хх | Цц | Чч | Шш | Щщ | Ъъ | Ыы | Ьь | Ээ | Юю | Яя | |

| Buryat | Өө | Пп | Рр | Сс | Тт | Уу | Үү | Хх | Һһ | Цц | Чч | Шш | Ыы | Ьь | Ээ | Юю | Яя | |||

| Kalmyk | Өө | Пп | Рр | Сс | Тт | Уу | Үү | Хх | Цц | Чч | Шш | Ьь | Ээ | Юю | Яя |

Khalkha

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з | И и | Й й |

| К к | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | Ө ө | П п | Р р | С с | Т т | У у |

| Ү ү | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ы ы | Ь ь | Э э |

| Ю ю | Я я |

- В в = /w/

- Е е = /jɛ/, /jœ/

- Ё ё = /jo/

- Ж ж = /dʒ/

- З з = /dz/

- Н н = /n-/, /-ŋ/

- Ө ө = /œ/

- Ү ү = /y/

- Ы ы = /iː/ (after a hard consonant)

- Ь ь = /ĭ/ (extra short)

- Ю ю = /ju/, /jy/

- D d = /ji/

The Cyrillic letters Кк, Пп, Фф and Щщ are not used in native Mongolian words, but only for Russian loans.

Buryat

The Buryat (буряад) Cyrillic script is similar to the Khalkha above, but Ьь indicates palatalization as in Russian. Buryat does not use Вв, Кк, Фф, Цц, Чч, Щщ or Ъъ in its native words.

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з | И и | Й й |

| Л л | М м | Н н | О о | Ө ө | П п | Р р | С с | Т т | У у | Ү ү |

| Х х | Һ һ | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Ы ы | Ь ь | Э э | Ю ю | Я я |

- Е е = /jɛ/, /jœ/

- Ё ё = /jo/

- Ж ж = /dʒ/

- Н н = /n-/, /-ŋ/

- Ө ө = /œ/

- Ү ү = /y/

- Һ һ = /h/

- Ы ы = /ei/, /iː/

- Ю ю = /ju/, /jy/

Kalmyk

The Kalmyk (хальмг) Cyrillic script is similar to the Khalkha, but the letters Ээ, Юю and Яя appear only word-initially. In Kalmyk, long vowels are written double in the first syllable (нөөрин), but single in syllables after the first. Short vowels are omitted altogether in syllables after the first syllable (хальмг = /xaʎmaɡ/).

| А а | Ә ә | Б б | В в | Г г | Һ һ | Д д | Е е | Ж ж | Җ җ | З з |

| И и | Й й | К к | Л л | М м | Н н | Ң ң | О о | Ө ө | П п | Р р |

| С с | Т т | У у | Ү ү | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Ь ь | Э э | Ю ю |

| Я я |

- Ә ә = /æ/

- В в = /w/

- Һ һ = /ɣ/

- Е е = /ɛ/, /jɛ-/

- Җ җ = /dʒ/

- Ң ң = /ŋ/

- Ө ө = /œ/

- Ү ү = /y/

Caucasian languages

Northwest Caucasian languages

Living Northwest Caucasian languages are generally written using Cyrillic alphabets.

Abkhaz

Abkhaz is a Caucasian language, spoken in the Autonomous Republic of Abkhazia, Georgia.

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Гь гь | Ӷ ӷ | Ӷь Ӷь | Д д | Дә дә | Е е |

| Ж ж | Жь жь | Жә жә | З з | Ӡ ӡ | Ӡә ӡә | И и | Й й | К к | Кь кь |

| Қ қ | Қь қь | Ҟ ҟ | Ҟь ҟь | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | П п | Ҧ ҧ |

| Р р | С с | Т т | Тә тә | Ҭ ҭ | Ҭә ҭә | У у | Ф ф | Х х | Хь хь |

| Ҳ ҳ | Ҳә ҳә | Ц ц | Цә цә | Ҵ ҵ | Ҵә ҵә | Ч ч | Ҷ ҷ | Ҽ ҽ | Ҿ ҿ |

| Ш ш | Шь шь | Шә шә | Щ щ | Ы ы | Ҩ ҩ | Џ џ | Џь џь | Ь ь | Ә ә |

Northeast Caucasian languages

Northeast Caucasian languages are generally written using Cyrillic alphabets.

Avar

Avar is a Caucasian language, spoken in the Republic of Dagestan, of the Russian Federation, where it is co-official together with other Caucasian languages like Dargwa, Lak, Lezgian and Tabassaran. All these alphabets, and other ones (Abaza, Adyghe, Chechen, Ingush, Kabardian) have an extra sign: palochka (Ӏ), which gives voiceless occlusive consonants its particular ejective sound.

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Гъ гъ | Гь гь | ГӀ гӀ | Д д |

| Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з | И и | Й й | К к | Къ къ |

| Кь кь | КӀ кӀ | КӀкӀ кӀкӀ | Кк кк | Л л | М м | Н н | О о |

| П п | Р р | С с | Т т | ТӀ тӀ | У у | Ф ф | Х х |

| Хх хх | Хъ хъ | Хь хь | ХӀ хӀ | Ц ц | Цц цц | ЦӀ цӀ | ЦӀцӀ цӀцӀ |

| Ч ч | ЧӀ чӀ | ЧӀчӀ чӀчӀ | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ы ы | Ь ь |

| Э э | Ю ю | Я я |

- В = /w/

- гъ = /ʁ/

- гь = /h/

- гӀ = /ʕ/

- къ = /qːʼ/

- кӀ = /kʼ/

- кь = /t͡ɬːʼ/

- кӀкӀ = /t͡ɬː/, is also written ЛӀ лӀ.

- кк = /ɬ/, is also written Лъ лъ.

- тӀ = /tʼ/

- х = /χ/

- хъ = /qː/

- хь = /x/

- хӀ = /ħ/

- цӀ = /t͡sʼ/

- чӀ = /t͡ʃʼ/

- Double consonants, called "fortis", are pronounced longer than single consonants (called "lenis").

Lezgian

Lezgian is spoken by the Lezgins, who live in southern Dagestan and northern Azerbaijan. Lezgian is a literary language and an official language of Dagestan.

Other

- Chechen (since 1938, also with Roman 1991–2000, but switch back to cyrillic alphabets since 2001.)

- Dargwa

- Kumyk

- Lak

- Tabassaran

- Ingush language

- Archi language

Turkic languages

Azerbaijani

- Cyrillic alphabet (first version 1939–1958)

- Аа, Бб, Вв, Гг, Ғғ, Дд, Ее, Әә, Жж, Зз, Ии, Йй, Кк, Ҝҝ, Лл, Мм, Нн, Оо, Өө, Пп, Рр, Сс, Тт, Уу, Үү, Фф, Хх, Һһ, Цц, Чч, Ҹҹ, Шш, Ыы, Ээ, Юю, Яя, ʼ

- Cyrillic alphabet (second version 1958–1991)

- Аа, Бб, Вв, Гг, Ғғ, Дд, Ее, Әә, Жж, Зз, Ии, Ыы, Јј, Кк, Ҝҝ, Лл, Мм, Нн, Оо, Өө, Пп, Рр, Сс, Тт, Уу, Үү, Фф, Хх, Һһ, Чч, Ҹҹ, Шш, ʼ

- Latin Alphabet (as of 1992)

- Aa, Bb, Cc, Çç, Dd, Ee, Əə, Ff, Gg, Ğğ, Hh, Iı, İi, Jj, Kk, Ll, Mm, Nn, Oo, Öö, Pp, Qq, Rr, Ss, Şş, Tt, Uu, Üü, Vv, (Ww), Xx, Yy, Zz

Bashkir

The Cyrillic script was used for the Bashkir language after the winter of 1938.

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Ғ ғ | Д д | Ҙ ҙ | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з | |

| И и | Й й | К к | Ҡ ҡ | Л л | М м | Н н | Ң ң | О о | Ө ө | П п | |

| Р р | С с | Ҫ ҫ | Т т | У у | Ү ү | Ф ф | Х х | Һ һ | Ц ц | Ч ч | |

| Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ы ы | Ь ь | Э э | Ә ә | Ю ю | Я я |

Chuvash

The Cyrillic alphabet is used for the Chuvash language since the late 19th century, with some changes in 1938.

| А а | Ӑ ӑ | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ӗ ӗ | Ж ж | З з |

| И и | Й й | К к | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | П п | Р р | С с | Ҫ ҫ |

| Т т | У у | Ӳ ӳ | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ы ы |

| Ь ь | Э э | Ю ю | Я я |

Kazakh

Kazakh can be alternatively written in the Latin alphabet. Latin is going to be the only used alphabet in 2022, alongside the modified Arabic alphabet (in the People's Republic of China, Iran and Afghanistan).

| А а | Ә ә | Б б | В в | Г г | Ғ ғ | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з |

| И и | Й й | К к | Қ қ | Л л | М м | Н н | Ң ң | О о | Ө ө | П п |

| Р р | С с | Т т | У у | Ұ ұ | Ү ү | Ф ф | Х х | Һ һ | Ц ц | Ч ч |

| Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ы ы | І і | Ь ь | Э э | Ю ю | Я я |

- Ә ә = /æ/

- Ғ ғ = /ʁ/ (voiced uvular fricative)

- Е е = /jɪ/

- И и = /ɪj~ɯj/

- Қ қ = /q/ (voiceless uvular plosive)

- Ң ң = /ŋ~ɴ/

- О о = /wʊ/

- Ө ө = /wʏ/

- У у = /ʊw/, /ʏw/, /w/

- Ұ ұ = /ʊ/

- Ү ү = /ʏ/

- Һ һ = /h/

- Ы ы = /ɯ/

- І і = /ɪ/

The Cyrillic letters Вв, Ёё, Цц, Чч, Щщ, Ъъ, Ьь and Ээ are not used in native Kazakh words, but only for Russian loans.

Kyrgyz

Kyrgyz has also been written in Latin and in Arabic.

| А а | Б б | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з | И и | Й й | К к |

| Л л | М м | Н н | Ң ң | О о | Ө ө | П п | Р р | С с | Т т | У у |

| Ү ү | Х х | Ч ч | Ш ш | Ы ы | Э э | Ю ю | Я я |

- Ң ң = /ŋ/ (velar nasal)

- Ү ү = /y/ (close front rounded vowel)

- Ө ө = /œ/ (open-mid front rounded vowel)

Tatar

Tatar has used Cyrillic since 1939, but the Russian Orthodox Tatar community has used Cyrillic since the 19th century. In 2000 a new Latin alphabet was adopted for Tatar, but it is used generally on the Internet.

| А а | Ә ә | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | Җ җ |

| З з | И и | Й й | К к | Л л | М м | Н н | Ң ң | О о | Ө ө |

| П п | Р р | С с | Т т | У у | Ү ү | Ф ф | Х х | Һ һ | Ц ц |

| Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ы ы | Ь ь | Э э | Ю ю | Я я |

- Ә ә = /æ/

- Ң ң = /ŋ/

- Ө ө = /œ/

- У у = /uw/, /yw/, /w/

- Ү ү = /y/

- Һ һ = /h/

- Җ җ = /ʑ/

The Cyrillic letters Ёё, Цц, Щщ are not used in native Tatar words, but only for Russian loans.

Turkmen

Turkmen, written 1940–1994 exclusively in Cyrillic, since 1994 officially in Roman, but in everyday communication Cyrillic is still used along with Roman script.

- Cyrillic alphabet

- Аа, Бб, Вв, Гг, Дд, Ее, Ёё, Жж, Җҗ, Зз, Ии, Йй, Кк, Лл, Мм, Нн, Ңң, Оо, Өө, Пп, Рр, Сс, Тт, Уу, Үү, Фф, Хх, (Цц) ‚ Чч, Шш, (Щщ), (Ъъ), Ыы, (Ьь), Ээ, Әә, Юю, Яя

- Latin alphabet version 2

- Aa, Ää, Bb, (Cc), Çç, Dd, Ee, Ff, Gg, Hh, Ii, Jj, Kk, Ll, Mm, Nn, Ňň, Oo, Öö, Pp, (Qq), Rr, Ss, Şş, Tt, Uu, Üü, (Vv), Ww, (Xx), Yy, Ýý, Zz, Žž

- Latin alphabet version 1

- Aa, Bb, , Çç, Dd, Ee, Êê Ff, Gg, Hh, Ii, Jj, Žž, Kk, Ll, Mm, Nn, Ññ, Oo, Ôô, Pp, Rr, Ss, Şş, Tt, Uu, Ûû, Ww, Yy, Ýý, Zz

Uzbek

From 1941 the Cyrillic script was used exclusively. In 1998 the government has adopted a Latin alphabet to replace it. The deadline for making this transition has however been repeatedly changed, and Cyrillic is still more common. It is not clear that the transition will be made at all.

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з | И и | Й й | К к |

| Л л | М м | Н н | О о | П п | Р р | С с | Т т | У у | Ф ф | Х х | Ч ч |

| Ш ш | Ъ ъ | Э э | Ю ю | Я я | Ў ў | Қ қ | Ғ ғ | Ҳ ҳ |

- В в = /w/

- Ж ж = /dʒ/

- Ф ф = /ɸ/

- Х х = /χ/

- Ъ ъ = /ʔ/

- Ў ў = /o/

- Қ қ = /q/

- Ғ ғ = /ʁ/

- Ҳ ҳ = /h/

Other

- Altay

- Balkar

- Crimean Tatar (1938–1991, also with Roman 1991–2014, but switched back to the Cyrillic alphabet in 2014.)

- Gagauz (1957–1990s, exclusively in Cyrillic, since 1990s officially in Roman, but in reality in everyday communication Cyrillic is used along with Roman script)

- Karachay

- Karakalpak (1940s–1990s)

- Karaim language (20th century)

- Khakas

- Kumyk

- Nogai

- Tuvan

- Uyghur – Uyghur Cyrillic alphabet (Uyghur Siril Yëziqi). Used along with Uyghur Arabic alphabet (Uyghur Ereb Yëziqi), " New Script " (Uyghur Yëngi Yëziqi, Pinyin-based), and modern Uyghur Latin alphabet (Uyghur Latin Yëziqi).

- Yakut

- Dolgan language

- Balkan Gagauz Turkish

- Urum language

- Siberian Tatar language

- Siberian Turkic language

Sinitic

Dungan language

Since 1953.

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | Җ җ | З з | И и | Й й |

| К к | Л л | М м | Н н | Ң ң | Ә ә | О о | П п | Р р | С с | Т т | У у |

| Ў ў | Ү ү | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ы ы | Ь ь | Э э |

| Ю ю | Я я |

- Letters in bold are used only in Russian loanwords.

Tungusic languages

- Even

- Evenk (since 1937)

- Nanai

- Udihe (Udekhe) (not used recently)

- Orok language (since 2007)

- Ulch language (since late 1980s)

Chukotko-Kamchatkan languages

- Chukchi (since 1936)

- Koryak (since 1936)

- Itelmen (since late 1980s)

- Alyutor language

Eskimo–Aleut languages

- Aleut (Bering dialect)

- Naukan Yupik language

- Central Siberian Yupik language

| А а | А̄ а̄ | Б б | В в | Г г | Ӷ ӷ | Гў гў | Д д | Д̆ д̆ | Е е | Е̄ е̄ | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з | И и | Ӣ ӣ |

| Й й | ʼЙ ʼй | К к | Ӄ ӄ | Л л | ʼЛ ʼл | М м | ʼМ ʼм | Н н | ʼН ʼн | Ӈ ӈ | ʼӇ ʼӈ | О о | О̄ о̄ | П п | Р р |

| С с | Т т | У у | Ӯ ӯ | Ф ф | Х х | Ӽ ӽ | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ы ы | Ы̄ ы̄ | Ь ь | Э э |

| Э̄ э̄ | Ю ю | Ю̄ ю̄ | Я я | Я̄ я̄ | ʼ | ʼЎ ʼў |

Other languages

- Ainu (in Russia)

- Korean (Koryo-mar)

- Assyrian Neo-Aramaic (Aisor)

- Ket (since 1980s)

- Nivkh

- Tlingit (in Russian Alaska)

- Yukaghir

Constructed languages

- International auxiliary languages

- Fictional languages

- Brutopian (Donald Duck stories)

- Syldavian (The Adventures of Tintin)

Summary table

| Early scripts | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Church Slavonic | А | Б | В | Г | Д | (Ѕ) | Е | Ж | Ѕ/З | И | І | К | Л | М | Н | О | П | Р | С | Т | Оу | (Ѡ) | Ф | Х | Ц | Ч | Ш | Щ | Ъ | Ы | Ѣ | Ь | Ю | Ꙗ | Ѥ | Ѧ | Ѩ | Ѫ | Ѭ | Ѯ | Ѱ | Ѳ | Ѵ | Ҁ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Most common shared letters | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common | А | Б | В | Г | Д | Е | Ж | З | И | Й | К | Л | М | Н | О | П | Р | С | Т | У | Ф | Х | Ц | Ч | Ш | Щ | Ь | Ю | Я | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| South Slavic languages | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulgarian | А | Б | В | Г | Д | Дж | Дз | Е | Ж | З | И | Й | К | Л | М | Н | О | П | Р | С | Т | У | Ф | Х | Ц | Ч | Ш | Щ | Ъ | Ь | Ю | Я | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Macedonian | А | Б | В | Г | Д | Ѓ | Е | Ѕ | Ж | З | И | Ј | К | Л | Љ | М | Н | Њ | О | П | Р | С | Т | Ќ | У | Ф | Х | Ц | Ч | Џ | Ш | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Serbian | А | Б | В | Г | Д | Ђ | Е | Ж | З | И | Ј | К | Л | Љ | М | Н | Њ | О | П | Р | С | Т | Ћ | У | Ф | Х | Ц | Ч | Џ | Ш | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Montenegrin | А | Б | В | Г | Д | Ђ | Е | Ж | З | З́ | И | Ј | К | Л | Љ | М | Н | Њ | О | П | Р | С | С́ | Т | Ћ | У | Ф | Х | Ц | Ч | Џ | Ш | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| East Slavic languages | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Russian | А | Б | В | Г | Д | Е | Ё | Ж | З | И | Й | К | Л | М | Н | О | П | Р | С | Т | У | Ф | Х | Ц | Ч | Ш | Щ | Ъ | Ы | Ь | Э | Ю | Я | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Belarusian | А | Б | В | Г | Д | Е | Ё | Ж | З | І | Й | К | Л | М | Н | О | П | Р | С | Т | У | Ў | Ф | Х | Ц | Ч | Ш | ’ | Ы | Ь | Э | Ю | Я | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ukrainian | А | Б | В | Г | Ґ | Д | Е | Є | Ж | З | И | І | Ї | Й | К | Л | М | Н | О | П | Р | С | Т | У | Ф | Х | Ц | Ч | Ш | Щ | ’ | Ь | Ю | Я | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rusyn | А | Б | В | Г | Ґ | Д | Е | Є | Ё | Ж | З | И | І | Ы | Ї | Й | К | Л | М | Н | О | П | Р | С | Т | У | Ф | Х | Ц | Ч | Ш | Щ | Ъ | Ѣ | Ь | Ю | Я | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Iranian languages | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kurdish | А | Б | В | Г | Г' | Д | Е | Ә | Ә' | Ж | З | И | Й | К | К' | Л | М | Н | О | Ö | П | П' | Р | Р' | С | Т | Т' | У | Ф | Х | Һ | Һ' | Ч | Ч' | Ш | Щ | Ь | Э | Ԛ | Ԝ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ossetian | А | Ӕ | Б | В | Г | Гъ | Д | Дж | Дз | Е | Ё | Ж | З | И | Й | К | Къ | Л | М | Н | О | П | Пъ | Р | С | Т | Тъ | У | Ф | Х | Хъ | Ц | Цъ | Ч | Чъ | Ш | Щ | Ъ | Ы | Ь | Э | Ю | Я | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tajik | А | Б | В | Г | Ғ | Д | Е | Ё | Ж | З | И | Ӣ | Й | К | Қ | Л | М | Н | О | П | Р | С | Т | У | Ӯ | Ф | Х | Ҳ | Ч | Ҷ | Ш | Ъ | Э | Ю | Я | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Romance languages | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Moldovan | А | Б | В | Г | Д | Е | Ж | Ӂ | З | И | Й | К | Л | М | Н | О | П | Р | С | Т | У | Ф | Х | Ц | Ч | Ш | Ы | Ь | Э | Ю | Я | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Uralic languages | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Komi-Permyak | А | Б | В | Г | Д | Е | Ё | Ж | З | И | І | Й | К | Л | М | Н | О | Ӧ | П | Р | С | Т | У | Ф | Х | Ц | Ч | Ш | Щ | Ъ | Ы | Ь | Э | Ю | Я | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Meadow Mari | А | Б | В | Г | Д | Е | Ё | Ж | З | И | Й | К | Л | М | Н | Ҥ | О | Ӧ | П | Р | С | Т | У | Ӱ | Ф | Х | Ц | Ч | Ш | Щ | Ъ | Ы | Ь | Э | Ю | Я | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hill Mari | А | Ӓ | Б | В | Г | Д | Е | Ё | Ж | З | И | Й | К | Л | М | Н | О | Ӧ | П | Р | С | Т | У | Ӱ | Ф | Х | Ц | Ч | Ш | Щ | Ъ | Ы | Ӹ | Ь | Э | Ю | Я | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kildin Sami | А | Ӓ | Б | В | Г | Д | Е | Ё | Ж | З | И | Й | Ҋ | Ј | К | Л | Ӆ | М | Ӎ | Н | Ӊ | Ӈ | О | П | Р | Ҏ | С | Т | У | Ф | Х | Һ | Ц | Ч | Ш | Щ | Ъ | Ы | Ь | Ҍ | Э | Ӭ | Ю | Я | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turkic languages | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bashkir | А | Ә | Б | В | Г | Ғ | Д | Ҙ | Е | Ё | Ж | З | И | Й | К | Ҡ | Л | М | Н | Ң | О | Ө | П | Р | С | Ҫ | Т | У | Ү | Ф | Х | Һ | Ц | Ч | Ш | Щ | Ъ | Ы | Ь | Э | Ә | Ю | Я | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chuvash | А | Ӑ | Б | В | Г | Д | Е | Ё | Ӗ | Ж | З | И | Й | К | Л | М | Н | О | П | Р | С | Ҫ | Т | У | Ӳ | Ф | Х | Ц | Ч | Ш | Щ | Ъ | Ы | Ь | Э | Ю | Я | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kazakh | А | Ә | Б | В | Г | Ғ | Д | Е | Ё | Ж | З | И | І | Й | К | Қ | Л | М | Н | Ң | О | Ө | П | Р | С | Т | У | Ұ | Ү | Ф | Х | Һ | Ц | Ч | Ш | Щ | Ъ | Ы | Ь | Э | Ю | Я | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kyrgyz | А | Б | Г | Д | Е | Ё | Ж | З | И | Й | К | Л | М | Н | Ң | О | Ө | П | Р | С | Т | У | Ү | Х | Ч | Ш | Ы | Э | Ю | Я | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tatar | А | Ә | Б | В | Г | Д | Е | Ё | Ж | Җ | З | И | Й | К | Л | М | Н | Ң | О | Ө | П | Р | С | Т | У | Ү | Ф | Х | Һ | Ц | Ч | Ш | Щ | Ъ | Ы | Ь | Э | Ю | Я | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Uzbek | А | Б | В | Г | Ғ | Д | Е | Ё | Ж | З | И | Й | К | Қ | Л | М | Н | О | П | Р | С | Т | У | Ў | Ф | Х | Ҳ | Ч | Ш | Ъ | Э | Ю | Я | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mongolian languages | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Buryat | А | Б | В | Г | Д | Е | Ё | Ж | З | И | Й | Л | М | Н | О | Ө | П | Р | С | Т | У | Ү | Х | Һ | Ц | Ч | Ш | Ы | Ь | Э | Ю | Я | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Khalkha | А | Б | В | Г | Д | Е | Ё | Ж | З | И | Й | К | Л | М | Н | О | Ө | П | Р | С | Т | У | Ү | Ф | Х | Ц | Ч | Ш | Щ | Ъ | Ы | Ь | Э | Ю | Я | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kalmyk | А | Ә | Б | В | Г | Һ | Д | Е | Ж | Җ | З | И | Й | К | Л | М | Н | Ң | О | Ө | П | Р | С | Т | У | Ү | Х | Ц | Ч | Ш | Ь | Э | Ю | Я | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Caucasian lannguages | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Abkhaz | А | Б | В | Г | Ҕ | Д | Дә | Џ | Е | Ҽ | Ҿ | Ж | Жә | З | Ӡ Ӡә | И | Й | К | Қ | Ҟ | Л | М | Н | О | Ҩ | П | Ҧ | Р | С | Т Тә | Ҭ Ҭә | У | Ф | Х | Ҳ Ҳә | Ц Цә | Ҵ Ҵә | Ч | Ҷ | Ш Шә | Щ | Ы | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sino-Tibetan languages | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dungan | А | Б | В | Г | Д | Е | Ё | Ж | Җ | З | И | Й | К | Л | М | Н | Ң | Ә | О | П | Р | С | Т | У | Ў | Ү | Ф | Х | Ц | Ч | Ш | Щ | Ъ | Ы | Ь | Э | Ю | Я | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

References

- Šmid (2002), pp. 113–24: "Es interesante el hecho que en Bulgaria se imprimieron unas pocas publicaciones en alfabeto cirílico búlgaro y en Grecia en alfabeto griego... Nezirović (1992: 128) anota que también en Bosnia se ha encontrado un documento en que la lengua sefardí está escrita en alfabeto cirilico." Translation: "It is an interesting fact that in Bulgaria a few [Sephardic] publications are printed in the Bulgarian Cyrillic alphabet and in Greece in the Greek alphabet... Nezirović (1992:128) writes that in Bosnia a document has also been found in which the Sephardic language is written in the Cyrillic alphabet."

- Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250, Cambridge Medieval Textbooks, Florin Curta, Cambridge University Press, 2006, ISBN 0521815398, pp. 221–222.

- The Orthodox Church in the Byzantine Empire, Oxford History of the Christian Church, J. M. Hussey, Andrew Louth, Oxford University Press, 2010, ISBN 0191614882, p. 100.

- Peshikan, Mitar; Jerković, Jovan; Pižurica, Mato (1994). Pravopis srpskoga jezika. Beograd: Matica Srpska. p. 42. ISBN 86-363-0296-X.

- Pravopis na makedonskiot jazik (PDF). Skopje: Institut za makedonski jazik Krste Misirkov. 2017. p. 3. ISBN 978-608-220-042-2.

- Senahid Halilović, Pravopis bosanskog jezika

- Rießler, Michael. Towards a digital infrastructure for Kildin Saami. In: Sustaining Indigenous Knowledge, ed. by Erich Kasten, Erich and Tjeerd de Graaf. Fürstenberg, 2013, 195–218.

Further reading

- Ivan G. Iliev. Short History of the Cyrillic Alphabet. Plovdiv. 2012. Short History of the Cyrillic Alphabet

- Philipp Ammon: Tractatus slavonicus. in: Sjani (Thoughts) Georgian Scientific Journal of Literary Theory and Comparative Literature, N 17, 2016, pp. 248–56

- Appendix:Cyrillic script, Wiktionary

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cyrillic alphabets. |

| Look up Appendix:Cyrillic script in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Cyrillic Alphabets of Slavic Languages review of Cyrillic charsets in Slavic Languages.