Flanders campaign

The Flanders Campaign (or Campaign in the Low Countries) was conducted from 6 November 1792 to 7 June 1795 during the first years of the French Revolutionary Wars. A Coalition of states representing the Ancien Régime in Western Europe – Austria (including the Southern Netherlands), Prussia, Great Britain, the Dutch Republic (the Northern Netherlands), Hanover and Hesse-Kassel – mobilised military forces along all the French frontiers, with the intention to invade Revolutionary France and end the French First Republic. The radicalised French revolutionaries, who broke the Catholic Church's power (1790), abolished the monarchy (1792) and even executed the deposed king Louis XVI of France (1793), vied to spread the Revolution beyond France's borders, by violent means if necessary.

| Flanders Campaign | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the First Coalition | |||||||

French commander Jourdan at the Battle of Fleurus. 1837 painting by Mauzaisse. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| |||||||

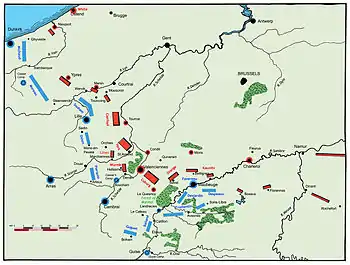

A quick French success in the Battle of Jemappes in November 1792 was followed by a major Coalition victory at Neerwinden in March 1793. After this initial stage, the largest of these forces assembled on the Franco-Flemish border. In this theatre a combined army of Anglo-Hanoverian, Dutch, Hessian, Imperial Austrian and, south of the river Sambre, Prussian troops faced the Republican Armée du Nord, and (further to the south) two smaller forces, the Armée des Ardennes and the Armée de la Moselle. The Allies enjoyed several early victories, but were unable to advance beyond the French border fortresses. Coalition forces were eventually forced to withdraw by a series of French counter-offensives, and the May 1794 Austrian decision to redeploy any troops in Poland.

The Allies established a new front in the south of the Netherlands and Germany, but with failing supplies and the Prussians pulling out they were forced to continue their retreat through the arduous winter of 1794/5. The Austrians pulled back to the lower Rhine and the British to Hanover from where they were eventually evacuated. The victorious French were aided in their conquest by Patriots from the Netherlands, who had previously been forced to flee to France after their own revolutions in the north in 1787 and in the south in 1789/91 had failed. These Patriots now returned under French banners as "Batavians" and "Belgians" to 'liberate' their countries. The republican armies pushed on to Amsterdam and early in 1795 replaced the Dutch Republic with a client state, the Batavian Republic, whilst the Austrian Netherlands and the Prince-Bishopric of Liège were annexed by the French Republic.

Prussia and Hesse-Kassel would recognise the French victory and territorial gains with the Peace of Basel (1795). Austria would not acknowledge the loss of the Southern Netherlands until the 1797 Treaty of Leoben and later the Treaty of Campo Formio. The Dutch stadtholder William V, Prince of Orange, who had fled to England, also initially refused to recognise the Batavian Republic, and in the Kew Letters ordered all Dutch colonies to temporarily accept British authority instead. Not until the 1801 Oranienstein Letters would he recognise the Batavian Republic, and his son William Frederick accept the Principality of Nassau-Orange-Fulda as compensation for the loss of the hereditary stadtholderate.

Background

Austria and Prussia had been at war with France since 20 April 1792, although Britain and the Dutch Republic initially maintained a neutral policy towards the revolution in France. Only after the execution of the French king Louis XVI on 21 January 1793 and the declaration of war by the Revolutionary Government did they finally mobilize. British Prime Minister Pitt the Younger pledged to finance the formation of the First Coalition, consisting of Britain, the Dutch Republic, Prussia, Austria and member states of the Holy Roman Empire, the Kingdom of Sardinia and Spain. Allied armies mobilised along all of the French frontiers, the largest and most important in the Flanders Franco-Belgian border region.

.png.webp)

In the north, the allies' immediate aim was to eject the French from the Dutch Republic (modern The Netherlands) and the Austrian Netherlands (modern Belgium), then march on Paris to end the chaotic and bloody French version of republican government. Austria and Prussia broadly supported this aim, but both were short of money. Britain agreed to invest a million pounds to finance a large Austrian army in the field plus a smaller Hanoverian corps, and dispatched an expeditionary force that eventually grew to approximately twenty thousand British troops under the command of the king's younger son, the Duke of York.[1] Initially, just fifteen hundred troops landed with York in February 1793.

Overall Allied command was led by the Austrian commander Prince Josias of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, with a staff of Austrian advisers answering to Emperor Francis II and the Austrian Foreign Minister Johann, Baron Thugut. The Duke of York was obliged to follow objectives set by Pitt's Foreign Minister Henry Dundas. Thus Allied military decisions in the campaign were tempered by political objectives from Vienna and London.

The defences of the Dutch Republic were in poor condition, its States Army not having fought in a war for 45 years. In the period 1785–1787 opponents of Stadtholder William V, Prince of Orange, the Patriots, had launched the Patriot revolt which only with difficulty had been suppressed after Prussian and British intervention in 1787, after which the leaders of the Patriots fled to France. William's main concern therefore was the preservation of the House of Orange and the authoritarian Stadtholderate regime.

Opposing the Allies, the armies of the French Republic were in a state of disruption; old soldiers of the Ancien Régime fought side by side with raw volunteers, urged on by revolutionary fervour from the Représentant en mission. Many of the old officer class had emigrated, leaving the cavalry in particular in chaotic condition. Only the artillery arm, less affected by emigration, had survived intact. The problems would become even more acute following the introduction of mass conscription, the Levée en Masse, in 1793. French commanders balanced between maintaining the security of the frontier, and clamours for victory (which would protect the regime in Paris) on the one hand, and the desperate condition of the army on the other, while they themselves were constantly under suspicion from the representatives. The price of failure or disloyalty was the guillotine.

The first skirmishes on the northern front took place during the battles of Quiévrain and Marquain (28–30 April 1792), in which ill-prepared French revolutionary armies were easily expelled from the Austrian Netherlands. The revolutionaries were forced on the defensive for months, losing Verdun and barely saving Thionville until the Coalition's unexpected defeat at Valmy (20 September 1792) turned the tables, and opened up a new opportunity for a northward invasion. The fresh momentum emboldened the revolutionaries to definitively abolish the monarchy and proclaim the French First Republic the very next day.

1793 campaign

By the end of 1792, following his surprise victory over the Imperial command under the Duke of Saxe-Teschen and Clerfayt at the Battle of Jemappes (6 November 1792), French commander Charles François Dumouriez had marched largely unopposed across most of the Austrian Netherlands, an area that roughly corresponds to present-day Belgium. As the Austrians retreated, Dumouriez saw an opportunity with the Patriot exiles to overthrow the weak Dutch Republic by making a bold move north. A second French Division under Francisco de Miranda manoeuvred against the Austrians and Hanoverians in eastern Belgium.

Dumouriez's invasion of the Dutch Republic

On 16 February Dumouriez's republican Armée du Nord advanced from Antwerp and invaded Dutch Brabant. Dutch forces fell back to the line of the Meuse abandoning the fortress of Breda after a short siege, and the Stadtholder called on Britain for help. Within nine days an initial British guards brigade had been assembled and dispatched across the English Channel, landing at Hellevoetsluis under the command of general Lake and the Duke of York.[2] Meanwhile, while Dumouriez moved north into Brabant, a separate army under Francisco de Miranda laid siege to Maastricht on 23 February. However the Austrians had been reinforced to 39,000 and, now commanded by Saxe-Coburg, crossed the Roer River on 1 March and drove back the Republican French near Aldenhoven. The next day the Austrians took Aachen before reaching Maastricht on the Meuse and forcing Miranda to lift the siege.

In the northern part of this theatre, Coburg thwarted Dumouriez's ambitions with a series of victories that evicted the French from the Austrian Netherlands altogether. This successful offensive reached its climax when Dumouriez was defeated at the Battle of Neerwinden on 18 March, and again at Louvain on 21 March.[3] Dumouriez defected to the Allies on 6 April and was replaced as head of the Armée du Nord by general Picot de Dampierre. France faced attacks on several fronts, and few expected the war to last very long.[4] However, instead of capitalising on this advantage, the Allied advance became pedestrian. The large Coalition army on the Rhine under the Duke of Brunswick was reluctant to advance due to hopes for a political settlement. The Coalition Army in Flanders had the opportunity to brush past Dampierre's demoralised army, but the Austrian staff was not fully aware of the degree of the French weakness and, while awaiting the arrival of reinforcements from Britain, Hanover and Prussia, turned instead to besiege fortresses along the French borders. The first objective was Condé-sur-l'Escaut, at the confluence of the Haine and Scheldt rivers.

Coalition spring offensive

At the beginning of April the Allied powers met in conference at Antwerp to agree their strategy against France. Coburg was a reluctant leader and had hoped to end the war through diplomacy with Dumouriez, he even issued a proclamation declaring he was the 'ally of all friends of order, abjuring all projects of conquest in the Emperors name', which he was immediately forced to recant by his political masters.[5] The British desired Dunkirk as an indemnity against the war, and proposed that they would support Coburg's military campaign provided the Austrians supported their politically inspired designs on Dunkirk. Coburg eventually proposed they attack Condé and Valenciennes in turn, then move against Dunkirk.

On the Rhine front the Prussians besieged Mainz, which held out from 14 April to 23 July 1793, and simultaneously mounted an offensive that swept through the Rhineland, mopping up small and disorganized elements of the French army. Meanwhile, in Flanders, Coburg began investing the French fortifications at Condé-sur-l'Escaut, now reinforced by the Anglo-Hanoverian corps of the Duke of York and Prussian contingent of Alexander von Knobelsdorff. Facing the allies, though his men desperately needed rest and reorganisation, Dampierre was hampered and controlled by the representatives on mission.[6] On 19 April he attacked the Allies across a wide front at St. Amand but was beaten off. On 8 May the French attempted once more to relieve Condé, but, after a fierce combat at Raismes, in which Dampierre was mortally wounded, the attempt failed.

The arrival of York and Knobelsdorff raised Coburg's command to upwards of 90,000 men, which allowed Coburg to next move against Valenciennes. On 23 May York's Anglo-Hanoverian forces saw their debut action at the Battle of Famars. In the same region of the Pas-de-Calais, the French, now under François Joseph Drouot de Lamarche, were driven back in a combined operation which prepared the way for the siege of Valenciennes. Command of the Armée du Nord was given to Adam Custine, who had enjoyed success on the Rhine in 1792; however Custine needed time to re-organise the demoralised army and fell back to the stronghold of Caesar's Camp near Bohain. Stalemate ensued as Custine felt unable to take the offensive and the allies focused on the sieges of Condé and Valenciennes. In July these both fell, Condé on 10 July, Valenciennes on 28 July. Custine was promptly recalled to Paris to answer for his tardiness, and guillotined.

Autumn campaign

On 7/8 August the French, now under Charles Kilmaine were driven from Caesar's Camp north of Cambrai. The following week in the Tourcoing sector Dutch troops under the Hereditary Prince of Orange attempted to repeat the success but were roughly handled by Jourdan at Lincelles until extricated by the British Guards brigade.[7][8]

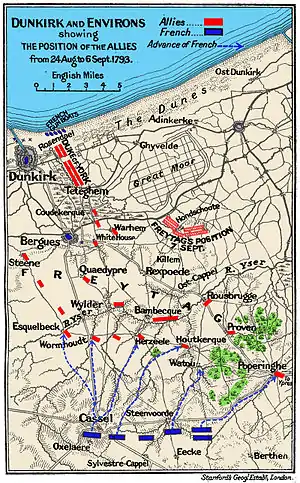

France was now at the mercy of the Coalition. The fall of Condé and Valenciennes had opened a gap in the frontier defences. The republican field armies were in disorder. However, instead of concentrating, the Allies now dispersed their forces.[9] In the south Knobelsdorf's Prussian contingent departed to join the main Prussian army on the Rhine front, while in the north York was under orders from Secretary of State Dundas to lay siege to the French port of Dunkirk, which the British government planned to use as a military base and bargaining counter in any future peace negotiation.[3] This led to conflict with Coburg,[10] who needed the occupying forces to protect his flank by accompanying his thrust towards Cambrai. Lacking York's support the Austrians chose instead to besiege Le Quesnoy, which was invested by Clerfayt on 19 August.

York's forces began the investment of Dunkirk, though they were ill-prepared for a protracted siege and had still not received any heavy siege artillery. The Armée du Nord, now under command of Jean Nicolas Houchard defeated York's exposed left flank under the Hanoverian general Freytag at the Battle of Hondschoote, forcing York to raise the siege and abandon his equipment. The Anglo-Hanoverians fell back in good order to Veurne (Furnes), where they were able to recover as there was no French pursuit. Houchard's plan had actually been to merely repulse the Duke of York so he could march south to relieve Le Quesnoy; on 13 September he defeated the Hereditary Prince at Menin (Menen), capturing 40 guns and driving the Dutch towards Bruges and Ghent, but three days later his forces were routed in turn by Beaulieu at Courtrai.

Further south Coburg meanwhile had captured Le Quesnoy on 11 September, enabling him to move forces north to assist York, and winning a signal victory over one of Houchard's Divisions at Avesnes-le-Sec. As if these disasters were not enough for the French, news reached Paris that in Alsace the Duke of Brunswick had defeated the French at Pirmasens. The Jacobins were stirred into a ferocity of panic.[11] Laws were imposed that placed all lives and property at the disposal of the regime. For failing to follow up his victory at Hondschoote and the defeat at Menen, Houchard was accused of treason, arrested, and guillotined in Paris on 17 November.

At the end of September Coburg began investing Maubeuge, though the allied forces were now stretched. The Duke of York was unable to offer much support as his command was greatly weakened, not only by the strain of the campaign, but also by Dundas in London, who began withdrawing troops to reassign to the West Indies.[12] As a result, Houchard's replacement Jean-Baptiste Jourdan was able to concentrate his forces and narrowly defeat Coburg at the Battle of Wattignies, forcing the Austrians to lift the siege of Maubeuge. The Convention then ordered a general offensive towards York's base at Ostend. In mid October Vandamme laid siege to Nieuport, MacDonald took Werwicq and Dumonceau drove the Hanoverians from Menen, however the French were forced back in sharp rebuffs at Cysoing on 24 October and Marchiennes on 29 October, which effectively brought an end to the year's campaigning.

1794–5 Campaign

Over the winter both sides re-organised. Reinforcements were transported from Britain in order to shore up the Coalition line.[13] In the Austrian army Coburg's Chief of Staff Prince Hohenlohe was replaced by Karl Mack von Leiberich. At the beginning of 1794 the allied field army numbered somewhat over one hundred thousand, the bulk of the army in positions between Tournai and Bettignies, with both flanks further extended with small outposts and cordons to the Meuse on the left and the Channel coast on the right. Facing them the Armée du Nord was now under the command of Jean-Charles Pichegru, and had been greatly reinforced by conscripts as the result of the Levée en masse, giving the combined strength of the Armies of the North and Ardennes (excluding garrisons) as 200,000, nearly two to one of Coburg's force.[14]

Siege of Landrecies

At the beginning of April 1794, Austrian troops were greatly encouraged when the Emperor Francis II joined Coburg at Allied headquarters. The first action of the campaign was a French advance from Le Cateau on 25 March, which was beaten off by Clerfayt after a sharp fight. Two weeks later the Allies began their advance with a series of covered marches and small actions to facilitate the investment of the fortress of Landrecies. York advanced from Saint-Amand towards Le Cateau, Coburg led the centre column from Valenciennes and Le Quesnoy, and to his left the Hereditary Prince led the besieging corps from Bavay through the Forest of Mormal towards Landrecies. On 17 April York drove Goguet from Vaux and Prémont, while the Austrian forces advanced in the direction of Wassigny against Balland.[7] The Hereditary Prince then began the Siege of Landrecies, while the Allied army covered the operation in a semi-circle. On the Left at the eastern end of the line lay the commands of Alvinczi and Kinsky, stretching from Maroilles four miles east of Landrecies, south to Prisches, then south-west to the line of the Sambre river. On the western bank of the river the line ran west from Catillon towards Le Cateau and Cambrai. The right of the Allied line was under the Duke of York and ended near Le Cateau. A line of outposts then ran north-west along the line of the Selle river.

The French plan was to attack both flanks of the allies, while sending relief columns towards Landrecies. On 24 April a small force of British and Austrian cavalry drove back just such a force under Chapuis at Villers-en-Cauchies. Two days later Pichegru launched a three-pronged attempt to relieve Landrecies. Two of the columns in the east were repulsed by the forces of Kinsky, Alvinczi and the young Archduke Charles, while Chapuis's third column advancing from Cambrai was all but destroyed by York at Beaumont/Coteau/Troisvilles on 26 April.[7][8]

The French counter-offensive

Landrecies fell on 30 April 1794 and Coburg turned his attention to Maubeuge, the last remaining obstacle to an advance on the French interior, but on the same day Pichegru began his overdue northern counter-offensive, defeating Clerfayt at the Battle of Mouscron and retaking Courtrai (Kortrijk) and Menen.

For 10 days a lull descended as both sides consolidated before Coburg launched attacks to regain the northern positions on 10 May. Jacques Philippe Bonnaud's French column was defeated by York at Willems, but Clerfayt failed to recapture Courtrai and was again driven back from the Lys River.

The Coalition forces planned to stem Pichegru's advance with a broad attack involving several isolated columns in a scheme devised by Mack. At the Battle of Tourcoing on 17–18 May this effort became a logistical disaster as communications broke down and columns were delayed. Only a third of the allied force came into action, and were only extricated after the loss of 3,000 men.[15] Pichegru being absent on the Sambre, French command at Tourcoing had devolved onto the shoulders of Joseph Souham. On his return to the front Pichegru renewed the offensive to press his advantage but despite repeated attacks was held off at the Battle of Tournay on 22 May.

Although the allied front remained intact, subsequently the Austrian commitment to the war became increasingly weakened. The Prussians were already on the point of pulling out of the war due to perceived Austrian duplicity in Bavaria. The Emperor was strongly influenced by Foreign Minister Baron Johann von Thugut, and for Thugut political considerations always overrode military plans. In May 1794 his fixation was with profiting from the Third Partition of Poland, and troops and generals began to be stripped from Coburg's command. Mack resigned as Chief-of-Staff in disgust on 23 May and was replaced by Prince Christian August von Waldeck-Pyrmont, a supporter of Thugut. In a Council of War on 24 May Emperor Francis II called for a vote on withdrawal, then left for Vienna. Only the Duke of York dissented with the withdrawal.[16]

Thugut's negative influence has been cited as one of the most decisive factors in the loss of the campaign, possibly more important than Tourcoing and Fleurus.[17] The decision to retreat was taken despite news of great gains on the southern flank. On 24 May Wichard Joachim Heinrich von Möllendorf's Prussians surprised the French at the Battle of Kaiserslautern, while on the same day Coburg's left wing under Franz Wenzel, Graf von Kaunitz-Rietberg, after beating off an attack on the Sambre had counter-attacked and routed the French right wing completely. With the northern flank temporarily stabilised Coburg moved forces south to support Kaunitz, who promptly resigned after being replaced by the Hereditary Prince. Pichegru then benefited from the weakening of the Allied northern sector to return to the offensive and initiate the Siege of Ypres. A series of supinely ineffective counter-attacks by Clerfayt through June were all beaten off by Souham.[18]

|

.jpg.webp) |

| Jean-Charles Pichegru | Jean-Baptiste Jourdan |

On the southern flank the French Army of the Moselle and Army of the Ardennes were combined with part of the right wing of the Army of the North under Jourdan, and after yet another failed attempt were finally able to cross the Sambre and lay siege to Charleroi. The following day Ypres surrendered to Pichegru. Coburg decided to concentrate most of his forces on the Sambre to drive Jourdan back, leaving York at Tournai and Clerfayt at Deinze to face Pichegru and cover the right. Clerfayt was soon driven from Deinze and retreated behind Ghent, obliging York to withdraw behind the Scheldt.

In the south Coburg launched a series of attacks against Jourdan's combined Army of Sambre-et-Meuse which were narrowly beaten off at the Battle of Fleurus 26 June. This proved the decisive turning point. With French gains in both north and south the Austrians called off the attack before a clear result and retreated north towards Brussels. It was the beginning of a general retreat to the Rhineland, the Austrians all but abandoning their 80-year-long control of the Austrian Netherlands.[n 1] York's Anglo-Hanoverians on the right were obliged to withdraw in order to defend Antwerp, abandoning Ostend, the garrison of which under Lord Moira were able to break through encircling French forces and rejoin York on the Scheldt.[19]

The loss of Austrian support led to the collapse of the campaign.[7][8] None of the other Coalition partners had sufficient forces in the theatre to check the French advance, and they began to retreat northwards, abandoning Brussels (conquered by Pichegru on 11 July). Jourdan pressed the whole Austrian line in repeated actions through the early days of July, encouraging Coburg's retreat back to Tienen (Tirlemont) and beyond, while York withdrew to the Dijle river. Although still ostensibly subordinate to Austrian command, the Dutch and Anglo-Hanoverian forces were now separated and moved to protect the Dutch Republic. Mechelen (Malines) fell on the 15th, Antwerp was evacuated on the 24th, the same day the Duke of York crossed the Dutch frontier at Roosendaal, while the Austrians crossed the Meuse at Maastricht.[20] Three days later, Pichegru occupied Antwerp. Meanwhile, Jourdan took Namur on 17 July, and Liège on 27 July, abolishing the Prince-Bishopric for the third time since 1789, this time for good. The demolition of Saint Lambert's Cathedral, in revolutionary eyes the symbol of clerical power and oppression, was initiated.

Fall of the Dutch Republic

In August 1794 a pause in operations fell as the French focused their efforts against the Belgian Channel ports (Sluis fell on 26 August), and York attempted in vain to encourage Austrian support. Under pressure from Britain, the Emperor dismissed Coburg, however his place was filled temporarily by the even more unpopular Clerfayt. After the fall of Le Quesnoy and Landrecies to the French, Pichegru renewed his offensive on the 28th, obliging York to pull back to the line of the Aa River where he was attacked at Boxtel and persuaded to withdraw to the Meuse. On 18 September Clerfayt was defeated at the Battle of Sprimont on the banks of the Ourthe, followed by a further defeat at the hands of Jourdan at the Battle of Aldenhoven on the Roer River on 2 October, causing the Austrians to retreat to the Rhine and finally ending Austrian presence in the Low Countries. Only the garrison in the strong fortress of Luxembourg City remained, but beginning on 22 November, it would be heavily beleaguered for seven months.

By autumn, in the Netherlands the French, including Herman Willem Daendels' Dutch Patriots, had taken Eindhoven and paused their pursuit on the Waal. The Dutch Orangists surrendered 's-Hertogenbosch (Bois-le-Duc) on 12 October after a heavy 3-week siege. York planned a counter-offensive with Austrian assistance to relieve Nijmegen, but this was abandoned when the Hanoverian contingent backed out. On 7 November, after a brief siege, Nijmegen was found to be untenable and the city also abandoned to the French. York made preparations to defend the line of the Waal through the winter but in early December he was recalled to England. In his absence, Hanoverian Lieutenant General Count von Walmoden took charge of the allied army while William Harcourt.[21] commanded the British contingent. At this stage the Prussians were in peace talks with the French, and Austria looked to be ready to follow suit. William Pitt the Younger angrily rejected any suggestion of negotiating with France,[21] but the British position in the Dutch Republic looked increasingly insecure.[22]

On 10 December, troops under Herman Willem Daendels assaulted across the Meuse in an unsuccessful attack on Dutch defences in the Bommelerwaard. However, in the days that followed, temperatures plummeted and the rivers Meuse and Waal began to freeze solid, allowing the French to resume their advance. By 28 December the French had occupied the Bommelwaard and the Lands of Altena. Brigades of Delmas' division, under Herman Willem Daendels and Pierre-Jacques Osten, moving at will, infiltrated the Dutch Water Line and captured fortifications and towns along a twenty-mile front.[23] When French vanguard troops crossed the Waal, British and Hessian forces made successful counterattacks at Tuil and Geldermalsen but on 10 January Pichegru ordered a general advance across the frozen river between Zaltbommel and Nijmegen and the allies were forced to retreat behind the Lower Rhine. On 15 January, the Anglo-Hanoverian army withdrew from their positions and began a retreat towards Germany, via Amersfoort, Apeldoorn and Deventer, in the face of a fierce blizzard. On 16 January, the city of Utrecht surrendered. Dutch revolutionaries led by Krayenhoff put pressure on the city council of Amsterdam on 18 January to hand over the city, which it did just after midnight, causing a pro-French Batavian Revolution. Earlier that day, stadtholder William V, Prince of Orange and his following had fled to exile in England. Dutch revolutionaries proclaimed the Batavian Republic on 19 January, and in the middle of a grand popular celebration on Dam Square they erected a liberty tree. In the afternoon, French troops entered the city and were cheered on by the people.[24] On 24 January the Capture of the Dutch fleet at Den Helder followed.

British evacuation

The British continued their retreat northwards, by now ill-equipped and poorly clothed.[25] By Spring 1795 they had left Dutch territory entirely, and reached the port of Bremen, a part of Hanover. There they waited for orders from Britain. Pitt, realizing that any imminent success on the continent was virtually impossible, at last gave the order to withdraw back to Britain, taking with them the remnants of the Dutch, German and Austrian troops that had retreated with them. York's army had lost more than 20,000 men in the two years of fighting.[26] On the embarkation of the most of British Army for England in April 1795 a small corps under General Dundas remained on the Continent until December the same year.[27] The surrender of Luxembourg on 7 June 1795 concluded the French conquest of the Low Countries, thus marking the end of the Flanders Campaign.

Aftermath

For the British and the Austrians the campaign proved disastrous. Austria had lost one of its territories, the Austrian Netherlands (largely constituting modern Belgium and Luxembourg), while the British had lost their closest ally on the European continent – the Dutch Republic. It would be more than twenty years before a friendly pro-British government was installed in The Hague again. Prussia, too, had abandoned the Prince of Orange who it had saved in 1787, and already signed a separate peace with France on 5 April, surrendering all its own possessions on the west Rhine bank (Prussian Guelders, Moers and half of Cleves). The Coalition fell apart even further when Spain admitted having lost the War of the Pyrenees, and defecting to the French side. Although Austria would continue its Rhine Campaigns successfully, it never regained foothold in the Southern Netherlands, and was continuously defeated by French forces under Napoleon in Northern Italy. It finally sued for peace in 1797 at Campo Formio, acknowledging the French conquest of the Netherlands.

In the British popular imagination York was widely (and inaccurately) portrayed as an incompetent dilettante, whose lack of military knowledge had led to disaster,[28] although historians such as Alfred Burne[29] and Richard Glover[30] strongly challenge this characterisation. The campaign however led to his ridicule in popular culture, although it did not stop him from holding future military commands, including a long tenure as Commander-in-Chief of the Army(1795–1809;1811–1827).

There were several reasons for the Allied failure in the campaign. Varying and conflicting objectives of the commanders, poor coordination between the various nations, appalling conditions for the troops, and outside interference from civilian politicians such as Henry Dundas[7] for the British and Thugut for the Empire. Also towards the end of the campaign in particular the gradual confidence and flexibility of the French armies compared to the more professional but outdated Allied forces became apparent.

The campaign demonstrated the numerous weaknesses of the British army after years of neglect, and a massive programme of reform was instigated by York in his new role as Commander-in-Chief.[31] While it performed strongly on many occasions, the Austrian army was plagued by the timidity and the conservatism of its commanders, whose movements were often very slow and inconclusive.

Both the British and the Austrians abandoned the Low Countries as their major theatre of operations, a drastic switch in strategy as it had previously been their main theatre in other European wars. Britain instead decided to use its maritime power to strike against French colonies in the West Indies. The Austrians now made the Italian front their main line of defence. Britain did briefly attempt to undertake an invasion of the Batavian Republic in 1799, again under the Duke of York, but this swiftly floundered and they were forced to conclude the Convention of Alkmaar and withdraw again.[32]

Legacy

In Britain one of the lasting associations with the campaign is the nursery rhyme "The Grand Old Duke of York", though it existed at least 200 years before the War. Alfred Burne mentions a virtually identical rhyme The King of France went up the Hill recorded in 1594.[33] There remains some considerable debate whether the rhyme refers to the later 1799 Helder campaign when York again led a British army into the Low Countries.[28]

For the British, lessons received in the campaign led to widespread army reforms on all levels, spearheaded by the Duke of York as Commander-in-Chief. The tight, professional army that later served in the Peninsular War was created on the foundation of lessons learned in 1794.

The Allies would not see such an opportunity to topple the new French regime again until 1814. For Austria and the Empire, the loss of the Austrian Netherlands was to have long-term effects as Republican domination in this region put a tremendous pressure on the order of the Holy Roman Empire, and was an instrumental factor in its later collapse in 1806. French control of the Netherlands enabled its armies to penetrate deep into Germany over the following years and later enabled Napoleon to establish the Continental System. For the French too, victory in the field served to solidify the perilous state of government at home. Following this campaign, the Army of the Sambre et Meuse became the chief offensive force, while the Armée du Nord was reduced to largely garrison status. Of the commanders, Coburg would never serve in the field again, nor too Pichegru who became discredited and later died in prison after involvement in plotting against Napoleon. The Duke of York was to lead a second expedition to Holland in the Helder Campaign in 1799, but after its failure was to remain as Commander-in-Chief at the Horse Guards for the rest of his career. The Hereditary Prince would have a checkered military career in the British (Helder 1799, Wight 1800), Prussian (Jena 1806) and Austrian (Wagram 1809) armies, before becoming king of the Kingdom of the United Netherlands in 1815, where a reconstituted Dutch army fought under his son, another Prince of Orange, in the Waterloo Campaign.

Many officers who would later rise to prominence received their baptism of fire on the fields of Flanders, including several of Napoleon's marshals – Bernadotte, Jourdan, Ney, MacDonald, Murat and Mortier. For the Austrians the Archduke Charles was given his first command there after replacing the wounded Alvinczi in 1794, while in the Hanoverian army Scharnhorst first saw action under the Duke of York.

In the British Army, the most notable debut was Arthur Wellesley (the future Duke of Wellington), who joined with his regiment the 33rd Regiment of Foot late in 1794 and served at the Battle of Boxtel.[34] He was to draw on these experiences during his own later more successful campaigns in India and the Peninsular War. Richard Sharpe says his first battle was the Battle of Boxtel.

Notes

- Rodger 2007, p. 426.

- Burne 1949, pp. 35–37.

- Harvey 2007, p. 126.

- Harvey 2007, p. 119.

- Fortescue 1918, p. 191.

- Phipps 1926, I p. 179.

- Fortescue 1918, .

- Burne 1949, .

- Phipps 1926, I p. 214.

- Fortescue 1918, p. 223.

- Fortescue 1918, p. 251.

- Fortescue 1918, pp. 253–254.

- Harvey 2007, p. 130.

- Fortescue 1918, p. 306.

- Fortescue 1918, pp. 331–342.

- Fortescue 1918, p. 346.

- Rothenburg 0000, p. 74-75.

- Fortescue 1918, p. 350.

- Fortescue 1918, p. 358.

- Fortescue 1918, pp. 362–365.

- Harvey 2007, p. 139.

- Holmes 2003, p. 31.

- Guthrie, William (1798). A New geographical, historical and commercial grammar and present state of the several kingdoms of the world, 1. 1798. printed for Charles Dilly ... and G.G. and J. Robinson. p. 473. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- Schama, pp. 178–192

- Holmes 2003, p. 29.

- Harvey 2007, p. 140.

- Vetch 1899, p. 97.

- Urban 2005, p. 98.

- Burne 1949.

- Glover.

- Glover, Richard(2008)Peninsular Preparation: The Reform of the British Army 1795–1809, Cambridge University Press

- Harvey 2007, pp. 333–334.

- Burne 1949, p. 15.

- Holmes 2003, pp. 28–32.

- The Austrian House of Habsburg acquired the Netherlands (the last independent northern provinces being conquered by 1543) in 1477 through marriage, inheriting them definitively in 1482. When the Habsburg empire was split in a Spanish and an Austrian part upon Charles V's abdication in 1556, the Netherlands became Spanish. Between 1598 and 1621, the Southern Netherlands were under Austrian control, whilst the northern provinces had become the de facto independent Dutch Republic as a result of the ongoing Eighty Years' War. The South became Spanish again in 1621, though the North's independence was recognised at the Peace of Münster in 1648. After the War of the Spanish Succession, the Southern Netherlands were once again transferred to Austria (1714), marking the beginning of what is known in historiography as the "Austrian Netherlands".

References

- Burne, Alfred (1949), The Noble Duke of York: The Military Life of Frederick Duke of York and Albany, London: Staples Press

- Fortescue, Sir John (1918), British Campaigns in Flanders 1690–1794 (extracts from Volume 4 of A History of the British Army), London: Macmillan

- Glover, Richard, Peninsular Preparation: The Reform of the British Army 1795–1809, year and publisher needed

- Holmes, Richard (2003), Wellington: The Iron Duke, London: Harper Collins, ISBN 0-00-713748-6.

- Phipps, Ramsay Weston (1926), The Armies of the First French Republic and the Rise of the Marshals of Napoleon I, London: Oxford University Press

- Rodger, N. A. M. (2007), Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain, 1649–1815, London: Penguin Books, ISBN 978-0-14-102690-9.

- Rothenburg, [Title, publisher, etc. missing]

- Urban, Mark (2005), Generals: Ten British Commanders Who Shaped the World, London: Faber and Faber, ISBN 0-571-22485-7.

- Vetch, Robert Hamilton (1899), , in Lee, Sidney (ed.), Dictionary of National Biography, 58, London: Smith, Elder & Co, pp. 97–98

Further reading

- Coutanceau, Michel Henri Marie (1903–08 5 Volumes), La Campagne de 1794 a l'Armée du Nord, Paris: Chapelot Check date values in:

|year=(help). - Brown, Robert (1795), An impartial Journal of a Detachment from the Brigade of Foot Guards, commencing 25 February 1793, and ending 9 May 1795, London.

- Hague, William (2005), William Pitt the Younger, London: Harper Perennial, ISBN 0-00-714720-1

- Harvey, Robert (2007), War of Wars: The Epic Struggle Between Britain and France 1789–1815, London: Robinson, ISBN 978-1-84529-635-3.

- Hibbert, Christopher (1998), George III: A Personal History, New York: Basic Books, ISBN 0-465-02723-7.

- Jones, Captain L. T. (1797), An Historical Journal of the British Campaign on the Continent in the Year 1794, London.

- Lambert, Andrew (2005), Nelson: Britannia's God of War, London: Faber and Faber, ISBN 0-571-21227-1.

- Officer of the Guards, An (1796), An Accurate and Impartial Narrative of the War, by an Officer of the Guards, London.

- Thiers, M (1845), A History of the French Revolution, London.

- Powell, Thomas (1968), The Diary of Lieutenant Thomas Powell, 14th Foot, 1793–1795, London: The White Rose.

- Pitt, W. & Rose, J. Holland (1909), "Pitt and the Campaign of 1793 in Flanders", English Historical Review, 24 (96): 744–749, doi:10.1093/ehr/XXIV.XCVI.744.

- Scarrow, Simon (1993), The Dutch Republic, London

- Schama, S. (1977), Patriots and Liberators. Revolution in the Netherlands 1780–1813, New York: Vintage Books, ISBN 0-679-72949-6.

- Tranié, Jean (1987), La Patrie en Danger 1792–1793, Paris: Lavauzelle, ISBN 2-7025-0183-4.

- Wills, Garry (2011), Wellington's First Battle, Grantham: Caseshot Publishing, ISBN 978-0-9567390-0-1.

In the arts

Blood on the Snow - by British author David Cook (2014) is a novella of the campaign.