Glycol cleavage

Glycol cleavage is a specific type of organic chemistry oxidation. The carbon–carbon bond in a vicinal diol (glycol) is cleaved and instead the two oxygen atoms become double-bonded to their respective carbon atoms. Depending on the substitution pattern in the diol, these carbonyls can be either ketones or aldehydes.

Glycol cleavage is an important reaction in the laboratory because it is useful for determining the structures of sugars. After cleavage takes place the ketone and aldehyde fragments can be inspected and the location of the former hydroxyl groups ascertained.[1]

Reagents

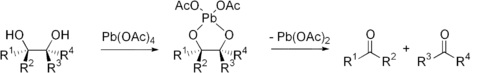

Periodic acid (HIO4) and lead tetraacetate (Pb(OAc)4) are the most common reagents used for glycol cleavage, processes called the Malaprade reaction and Criegee oxidation, respectively. These reactions are most efficient when a cyclic intermediate can form, with the iodine or lead atom linking both oxygen atoms. The ring then fragments, with breakage of the carbon–carbon bond and formation of carbonyl groups.

If an R group is a hydrogen atom, an aldehyde is formed at that site. If the R group is a chain that begins with a carbon atom, a ketone is formed.

Glycol cleavage with Pb(OAc)4 involves a cyclic intermediate.

Glycol cleavage with Pb(OAc)4 involves a cyclic intermediate.

Warm concentrated potassium permanganate (KMnO4) will react with an alkene to form a glycol. Following this dihydroxylation, the KMnO4 can then easily cleave the glycol to give aldehydes or ketones. The aldehydes will react further with (KMnO4), being oxidized to become carboxylic acids. Controlling the temperature and concentration of the reagent can keep the reaction from continuing past the formation of the glycol.

References

- Wade, L. G. Organic Chemistry, 6th ed.., Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, 2005; pp 358–361, pp 489–490. ISBN 0-13-147882-6