Maltitol

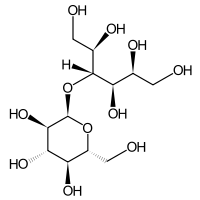

Maltitol is a sugar alcohol (a polyol) used as a sugar substitute. It has 75–90% of the sweetness of sucrose (table sugar) and nearly identical properties, except for browning. It is used to replace table sugar because it is half as energetic, does not promote tooth decay, and has a somewhat lesser effect on blood glucose. In chemical terms, maltitol is known as 4-O-α-glucopyranosyl-D-sorbitol. It is used in commercial products under trade names such as Lesys, Maltisweet and SweetPearl.

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

4-O-α-D-Glucopyranosyl-D-glucitol | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.008.699 |

| E number | E965 (glazing agents, ...) |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C12H24O11 | |

| Molar mass | 344.313 g·mol−1 |

| Melting point | 145 °C (293 °F; 418 K) |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Production and uses

Maltitol is a disaccharide produced by hydrogenation of maltose obtained from starch. Maltitol syrup, a hydrogenated starch hydrolysate, is created by hydrogenating corn syrup, a mixture of carbohydrates produced from the hydrolysis of starch. This product contains between 50% and 80% maltitol by weight. The remainder is mostly sorbitol, with a small quantity of other sugar-related substances.[1]

Maltitol's high sweetness allows it to be used without being mixed with other sweeteners. It exhibits a negligible cooling effect (positive heat of solution) in comparison with other sugar alcohols, and is very similar to the subtle cooling effect of sucrose.[2] It is used in candy manufacture, particularly sugar-free hard candy, chewing gum, chocolates, baked goods, and ice cream. The pharmaceutical industry uses maltitol as an excipient, where it is used as a low-calorie sweetening agent. Its similarity to sucrose allows it to be used in syrups with the advantage that crystallization (which may cause bottle caps to stick) is less likely. Maltitol may also be used as a plasticizer in gelatin capsules, as an emollient, and as a humectant.[3]

Nutritional information

Maltitol provides between 2 and 3 kcal/g.[4] Maltitol is largely unaffected by human digestive enzymes and is fermented by bacteria in the large intestine, with about 15% of the ingested maltitol appearing unchanged in the feces.[5]

Chemical properties

Maltitol in its crystallized form measures the same (bulk) as table sugar and browns and caramelizes in a manner very similar to that of sucrose after liquifying by exposure to intense heat. The crystallized form is readily dissolved in warm liquids (120 °F / 48.9 °C and above); the powdered form is preferred if room-temperature or cold liquids are used. Due to its sucrose-like structure, maltitol is easy to produce and made commercially available in crystallized, powdered, and syrup forms.

It is not metabolized by oral bacteria, so it does not promote tooth decay. It is somewhat more slowly absorbed than sucrose, which makes it somewhat more suitable for people with diabetes than sucrose. Its food energy value is 2.1 kcal/g (8.8 kJ/g); (sucrose is 3.9 kcal/g (16.2 kJ/g)).

Effects on digestion

Like other sugar alcohols (with the possible exception of erythritol), maltitol has a laxative effect,[6] typically causing diarrhea at a daily consumption above about 90 g.[7] Doses of about 40 g may cause mild borborygmus (stomach and bowel sounds) and flatulence.[8]

This effect was the subject of Netflix mockumentary American Vandal season 2.

Government warnings

In the European Union[9] and countries such as Australia, Canada, Norway, Mexico and New Zealand, maltitol carries a mandatory warning such as "Excessive consumption may have a laxative effect." In the United States, it is a generally recognized as safe (GRAS) substance, with a recommendation of a warning about its laxative potential when consumed at levels above 100 grams per day.

References

- Application A537 – Reduction in the energy factor assigned to Maltitol: Final Assessment Report (PDF), Food Standards Australia New Zealand, 5 October 2005, retrieved 27 January 2014

- Field, Simon Quellen; Simon Field (2007). Why There's Antifreeze in Your Toothpaste. pp. 86. ISBN 9781556526978.

- Cargill:Products and Services

- Franz, M. J.; Bantle, J. P.; Beebe, C. A.; Brunzell, J. D.; Chiasson, J.-L.; Garg, A.; Holzmeister, L. A.; Hoogwerf, B.; Mayer-Davis, E.; Mooradian, A. D.; Purnell, J. Q.; Wheeler, M. (2002). "Evidence-Based Nutrition Principles and Recommendations for the Treatment and Prevention of Diabetes and Related Complications". Diabetes Care. 25 (1): 148–198. doi:10.2337/diacare.25.1.148. PMID 11772915.

- Oku, T.; Akiba, M.; Lee, M. H.; Moon, S. J.; Hosoya, N. (October 1991). "Metabolic fate of ingested [14C]-maltitol in man". Journal of Nutritional Science and Vitaminology. 37 (5): 529–44. doi:10.3177/jnsv.37.529. PMID 1802977. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- Maltidex maltitol Archived 2016-04-05 at the Wayback Machine. Cargill – Food and Beverage Ingredients.

- Ruskoné-Fourmestraux, A.; Attar, A.; Chassard, D.; Coffin, B.; Bornet, F.; Bouhnik, Y. (2003). "A digestive tolerance study of maltitol after occasional and regular consumption in healthy humans". Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 57 (1): 26–30. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601516. PMID 12548293. S2CID 6975213.

- Mäkinen, K. K. (2016). "Gastrointestinal Disturbances Associated with the Consumption of Sugar Alcohols with Special Consideration of Xylitol: Scientific Review and Instructions for Dentists and Other Health-Care Professionals". Int. J. Dent. 2016: 5967907. doi:10.1155/2016/5967907. PMC 5093271. PMID 27840639.

- https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=LEGISSUM%3Al21069 EUR-Lex: Authorised sweeteners