Hungarian Socialist Party

The Hungarian Socialist Party (Hungarian: Magyar Szocialista Párt), known mostly by its acronym MSZP, is a social-democratic[1][2][3][4][5] political party in Hungary.

Hungarian Socialist Party Magyar Szocialista Párt | |

|---|---|

| Abbreviation | MSZP |

| Leader | Bertalan Tóth Ágnes Kunhalmi |

| Deputy President | Imre Komjáthi |

| Vice President | Zita Gurmai Gyula Hegyi |

| Parliamentary leader | Bertalan Tóth |

| Chairman of Board | István Hiller |

| Founded | 7 October 1989 |

| Preceded by | Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party |

| Headquarters | 1073 Budapest, VII. Erzsébet krt. 40–42. fsz. I-1. |

| Youth wing | Societas – Baloldali Ifjúsági Mozgalom |

| Ideology | Social democracy[1][2][3][4][5] Pro-Europeanism |

| Political position | Centre-left[6] |

| European affiliation | Party of European Socialists |

| International affiliation | Progressive Alliance Socialist International |

| European Parliament group | Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats |

| Colors | Red |

| National Assembly | 15 / 199 |

| European Parliament | 1 / 21 |

| County Assemblies | 18 / 381 |

| Party flag | |

| |

| Website | |

| mszp | |

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Hungary |

It was founded on 7 October 1989 as a post-communist evolution and one of two legal successors of the Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party (MSZMP). Along with its conservative rival Fidesz, MSZP was one of the two most dominant parties in Hungarian politics until 2010; however, the party lost much of its popular support as a result of the Őszöd speech, the consequent 2006 protests, and then the 2008 financial crisis. Following the 2010 election, MSZP became the largest opposition party in parliament, a position it held until 2018, when it was overtaken by the far-right Jobbik.

History

The MSZP evolved from the communist Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party (or MSZMP), which ruled Hungary between 1956 and 1989. By the summer of 1989, the MSZMP was no longer a Marxist–Leninist party, and had been taken over by a faction of radical reformers who favoured jettisoning the Communist system in favour of a market economy. One of its leaders, Rezső Nyers, the architect of the New Economic Mechanism in the 1960s and 1970s, was elected as chairman of a four-man collective presidency that replaced the old MSZMP Politburo. Although General Secretary Károly Grósz, who had succeeded longtime leader János Kádár a year earlier, was elected to this body, Nyers now outranked him–and was thus now the de facto leader of Hungary.

At a party congress on 7 October 1989, the MSZMP dissolved and refounded itself as the MSZP, with Nyers as its first president. A marginal "Communist" faction led by Grósz broke away to form a revived Hungarian Communist Workers' Party, now known as the Hungarian Workers' Party, the other successor of the MSZMP.

The decision to declare the MSZP a successor of the MSZMP was controversial, and still carries repercussions for both the MSZP and Hungary. Another source of controversy is that some members of the former communist elite maintained political influence in the MSZP. Indeed, many key MSZP politicians were active members or held leadership positions within the MSZMP (like Gyula Horn and László Kovács).

On economic issues, the Socialists have often been greater advocates of liberal, free market policies than the conservative opposition, which has tended to favor more state interventionism in the economy through economic and price regulations, as well as through state ownership of key economic enterprises. The MSZP, in contrast, implemented a strong package of market reforms, austerity and privatization in 1995–96, called the Bokros package, when Hungary faced an economic and financial crisis. According to researchers, the elites of the Hungarian 'left' (MSZP and SZDSZ) have been differentiated from the 'right' by being more supportive of the classical neo-liberal economic policies, while the 'right' (especially extreme right) has advocated more interventionist policies. In contrast, issues like church and state and former communists show alignment along the traditional left-right spectrum.[7] It is also noteworthy that, according to research, the MSZP elite's positions used to be closer to voters of the SZDSZ than to their own.[8]

Besides a more liberal approach to the economy overall, the MSZP differentiated itself from the conservative opposition through its more recent focus on transforming state social policy from a collection of measures that benefit the entire population, such as subsidies available to all citizens, to one based on financial and social need.

Besides Gyula Horn, the MSZP's most internationally recognized politicians were Ferenc Gyurcsány and László Kovács, a former member of the European Commission, responsible for taxation.

Electoral history

The MSZP faced the voters for the first time at the 1990 elections, the first free elections held in Hungary in 44 years. It was knocked down to fourth place with only 33 seats.

Nyers handed the leadership to Horn, Hungary's last Communist foreign minister. Horn led the MSZP to an outright majority at the 1994 parliamentary election. Although the MSZP could have governed alone, he opted to form a coalition with the liberal Alliance of Free Democrats (SZDSZ). He not only wanted to allay concerns inside and outside Hungary of a former Communist party holding a majority, but needed the Free Democrats' votes to get economic reforms (what became the Bokros package) past his own party's left wing. Thus the MSZP was released from a so-called "political quarantine" imposed by the other Hungarian parties; during the first five years after the change of system, the other parties cooperated to shut out the MSZP from decision-making.

After being turned out of office in 1998, the party was able to form a renewed centre-left coalition with the Free Democrats in 2002.

At the 2006 elections, MSZP won with 43.2% of party list votes, which gave it 190 representatives out of 386 in the Parliament. The MSZP was therefore able to retain its coalition government from the previous term. In earlier elections, the MSZP polled 10.89% (1990), 32.98% (1994), 32.92% (1998) and 42.05% (2002).

After the successful fees abolishment referendum, MSZP formed the first minority government of Hungary, following the SZDSZ's backing out of the coalition with a deadline of 1 May 2008.

2010s decline

On 21 March 2009 Gyurcsány announced his resignation as Prime Minister due to failure management of the economic crisis.[9][10] Gordon Bajnai became the nominee of MSZP for the post of prime minister in March 2009[11] and he became Prime Minister on 14 April. Gyurcsány also resigned from his position of party chairman, which he had occupied since 2007.[12]

MSZP lost half of its supporters during the European Parliament election in 2009, receiving only 17.37% of the votes and gained four seats compared to the previous nine seats. This electoral defeat marked the end of the de facto two-party system in Hungary, which had lasted since 1998.

The Hungarian Socialist Party suffered a heavy defeat in the 2010 election (won by Fidesz with a ⅔ majority), gaining only 19.3% of the votes, and 59 seats in the parliament. Following the resignation of Ildikó Lendvai, the party's prime minister candidate Attila Mesterházy was elected Chairman of the Socialist Party.[13] Nevertheless, MSZP became the biggest opposition party in Hungary.

The left-wing fragmented after the 2010 election; at first Katalin Szili left the MSZP to form Social Union (SZU), following the similarly significant defeated local elections in October 2010, nevertheless Gyurcsány's detachment was a much worse disaster for the Socialists. Initially, the former PM wanted to reform the party, but his goals remained in the minority. As a result, Gyurcsány, along with nine other members of the parliamentary group, left MSZP and established Democratic Coalition (DK). Thus MSZP's number of MPs reduced to 48.[14]

The Socialist Party entered into an alliance with four other parties in January 2014 to contest the April parliamentary election. Mesterházy was elected candidate for the Prime Minister position, but the Unity alliance failed to win. After that the electoral coalition disestablished.[15] On the 2014 European Parliament election, MSZP suffered the largest defeat since the 1990 parliamentary election, gaining third place and only 10% of the votes.[16] After the obvious failure, Mesterházy and the entire presidium of the Socialist Party resigned.[17][18]

József Tóbiás was elected leader of the Socialist Party on 19 July 2014 following the resignation of Mesterházy.[19] He also became leader of the parliamentary group in September 2014. During his leadership, the Socialist Party won a parliamentary by-election (2014) and an important mayoral by-election (Salgótarján), however the party itself was permanently pushed back to the third place by far-right Jobbik according to the opinion polls. Tóbiás did not support the full cooperation and unification of the left-wing opposition parties against Viktor Orbán. During the MSZP party congress in June 2016, he was defeated by Gyula Molnár, a former Socialist MP and mayor, who succeeded him as party chairman.[20] In February 2016, the party decided to sell its headquarters at Jókai Street for financial reasons. In June 2018, Bertalan Tóth was elected president in the MSZP, shortly after the party suffered its worst electoral defeat since 1990.[21]

The party further declined in the 2019 European election, only scoring 6.61% of votes (even in alliance with Dialogue for Hungary) and being overtaken by the Democratic Coalition and Momentum. In 2019 local elections the party managed (due to cooperation with other parties) to win mayorships ir Érd and Szombathely. Also in these elections MSZP managed to win mayorships in those areas, where it never had a mayor since 1990 (e. g. Mohács).

2019 local election results caused resignations from party on the local level (e. g. Szeged mayor Laszlo Botka).

In 2020, party's congress supported change to party's structure. Instead of having one leader, the party would nominate two co-leaders – man and woman (similar structure has been implemented in 2019 by the Social Democratic Party of Germany).[22]

Ideology

In political terms, the MSZP differentiates itself from its conservative opponents mainly in its rejection of Hungarian nationalism. The party is a member of the Progressive Alliance,[23] the Socialist International, and the Party of European Socialists (PES), and it holds a chairmanship and several vice-chairmanships in committees at the European Parliament.

Election results

National Assembly

| Election | Votes | Seats | Rank | Government | Leader of the national list | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | ±pp | # | +/− | ||||

| 1990 | 419,152 | 10.9% | – | 33 / 386 |

±0 | 4th | MDF–FKgP–KDNP | Rezső Nyers |

| MDF–EKGP–KDNP | ||||||||

| 1994 | 2,921,039 | 33.0% | 209 / 386 |

1st | MSZP-SZDSZ Supermajority | Gyula Horn | ||

| 1998 | 1,497,231 | 32.9% | 134 / 386 |

2nd | Fidesz-FKgP-MDF | Gyula Horn | ||

| 2002 | 2,361,997 | 42.0% | 178 / 386 |

1st | MSZP-SZDSZ | Péter Medgyessy | ||

| 2006 | 2,336,705 | 43.2% | 190 / 386 |

1st | MSZP-SZDSZ | Ferenc Gyurcsány | ||

| MSZP Minority | ||||||||

| 2010 | 990,428 | 19.3% | 59 / 386 |

2nd | Fidesz-KDNP Supermajority | Attila Mesterházy | ||

| 20141 | 1,290,806 | 25.57% | 29 / 199 |

2nd | Fidesz-KDNP Supermajority | Attila Mesterházy | ||

| 20182 | 682,701 | 11.91% | 17 / 199 |

3rd | Fidesz-KDNP Supermajority | Gergely Karácsony (Párbeszéd) | ||

1As part of the Unity alliance; MSZP ran together with Together 2014 (E14), Democratic Coalition (DK), Dialogue for Hungary (PM) and Hungarian Liberal Party (MLP).

2 In an electoral alliance with Dialogue for Hungary

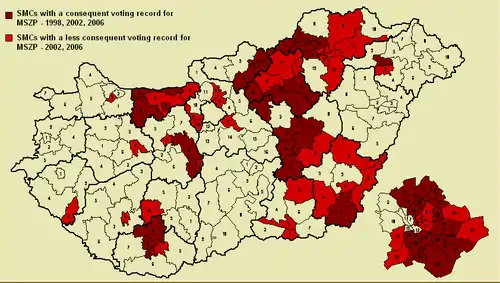

Single Member Constituencies voting consistently for MSZP

The image shows Single Member Constituencies (or SMCs) voting for MSZP in 1998, 2002, 2006 in dark red, while showing SMCs voting for MSZP in 2002 and 2006 in red. The dark red districts are considered the strongest positions of the party. Most if not all districts shown in dark red and red also voted for MSZP in 1994, a landslide victory for the party. So actually, dark red districts have an even longer uninterrupted voting history of supporting MSZP.

European Parliament

| Election year | # of overall votes | % of overall vote | # of overall seats won | +/- | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 1,054,921 | 34.3% (2nd) | 9 / 24 |

||

| 2009 | 503,140 | 17.37% (2nd) | 4 / 22 |

||

| 2014 | 252,751 | 10.9% (3rd) | 2 / 21 |

||

| 20191 | 229,551 | 6.61% (4th) | 1 / 21 |

1 In an electoral alliance with Dialogue for Hungary

Party leaders

Chairpersons (1989–2020)

| # | Image | Name | Entered office | Left office | Length of Leadership | Notice | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

Rezső Nyers | 9 October 1989 | 27 May 1990 | 230 days | ||

| 2 | .jpg.webp) |

Gyula Horn | 27 May 1990 | 5 September 1998 | 8 years, 101 days | Prime Minister 1994–98 | |

| 3 |  |

László Kovács | 5 September 1998 | 16 October 2004 | 6 years, 41 days | ||

| 4 |  |

István Hiller | 16 October 2004 | 24 February 2007 | 2 years, 131 days | ||

| 5 |  |

Ferenc Gyurcsány | 24 February 2007 | 5 April 2009 | 2 years, 40 days | Prime Minister 2004–09 | |

| 6 | .JPG.webp) |

Ildikó Lendvai | 5 April 2009 | 10 July 2010 | 1 year, 96 days | ||

| 7 |  |

Attila Mesterházy | 10 July 2010 | 29 May 2014 | 3 years, 323 days | ||

| – |  |

László Botka (interim) |

31 May 2014 | 19 July 2014 | |||

| 8 |  |

József Tóbiás | 19 July 2014 | 25 June 2016 | 1 year, 342 days | ||

| 9 | .jpg.webp) |

Gyula Molnár | 25 June 2016 | 17 June 2018 | 1 year, 357 days | ||

| 10 |  |

Bertalan Tóth | 17 June 2018 | 19 September 2020 | 2 years, 94 days | ||

Co-leaders (2020– )

| # | Image | Male co-chair | Image | Female co-chair | Entered office | Left office | Length of Leadership | Notice | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 |  |

Bertalan Tóth |  |

Ágnes Kunhalmi | 19 September 2020 | Incumbent | 137 days | ||

References

- Nordsieck, Wolfram (2018). "Hungary". Parties and Elections in Europe.

- Dimitri Almeida (27 April 2012). The Impact of European Integration on Political Parties: Beyond the Permissive Consensus. CRC Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-136-34039-0. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- José Magone (26 August 2010). Contemporary European Politics: A Comparative Introduction. Routledge. p. 456. ISBN 978-0-203-84639-1. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- Petr Kopecký; Peter Mair; Maria Spirova (26 July 2012). Party Patronage and Party Government in European Democracies. Oxford University Press. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-19-959937-0.

- Igor Guardiancich (21 August 2012). Pension Reforms in Central, Eastern and Southeastern Europe: From Post-Socialist Transition to the Global Financial Crisis. Routledge. p. 95. ISBN 978-1-136-22595-6.

- Freedom House (24 December 2013). Nations in Transit 2013: Democratization from Central Europe to Eurasia. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 255–. ISBN 978-1-4422-3119-1.

- Bodan Todosijević, "The Hungarian Voter: Left–Right Dimension as a Clue to Policy Preferences" in International Political Science Review (2004), Vol 25, No. 4, p. 421

- Bodan Todosijević"The Hungarian Voter: Left–Right Dimension as a Clue to Policy Preferences" in International Political Science Review (2004), Vol 25, No. 4, p. 424

- Kulish, Nicholas (22 March 2009). "Hungary's Premier Offers to Resign". The New York Times.

- "Hungarian PM offers to step down". Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- Edith Balazs and Charles Forelle (31 March 2009). "Hungary's Ruling Party Picks Premier". WSJ. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- "Hungary's PM resigns post as Socialist Party chairman_English_Xinhua". Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- "Mesterházy lett az MSZP elnöke". VG. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- "Gyurcsány announces departure from Socialists, formation of new "Western, civic center-left" party". Politics.hu. Archived from the original on 14 February 2015. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- "Socialists to delegate PM candidate for opposition alliance". 8 January 2014. Archived from the original on 9 January 2014. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- "Egyetlen ábrán megnézheti az MSZP tragédiáját". 25 May 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- "Mesterházy: Újabb leckét kaptunk". 25 May 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- "Mesterházy lemondott az MSZP vezetéséről". 29 May 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- "Hungarian Socialists picks Jozsef Tobias to head party". Xinhua. 20 July 2014. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- "Elzavarták Tóbiást, Molnár Gyula az MSZP új elnöke". Index.hu. 25 June 2016. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- Szabolcs, Dull (1 June 2018). "Tóth Bertalan az új elnök, Mesterházynak nem sikerült" (in Hungarian). Retrieved 18 June 2018.

- https://hungarytoday.hu/socialists-opposition-2022-election/

- "Participants". Archived from the original on 2 March 2015. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to MSZP. |