King's Lynn

King's Lynn, known until 1537 as Bishop's Lynn and colloquially as Lynn,[2] is a seaport and market town in Norfolk, England, 98 miles (158 km) north of London, 36 miles (58 km) north-east of Peterborough, 44 miles (71 km) north-north-east of Cambridge and 44 miles (71 km) west of Norwich.[2] The population is 42,800.[1]

| King's Lynn | |

|---|---|

King's Lynn Location within Norfolk | |

| Population | 42,800 (2007)[1] |

| • London | 98 miles (158 km) |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | KING'S LYNN |

| Postcode district | PE30-PE34 |

| Dialling code | 01553 |

| Police | Norfolk |

| Fire | Norfolk |

| Ambulance | East of England |

| UK Parliament | |

| Website | www.west-norfolk.gov.uk |

History

Toponymy

The etymology of King's Lynn is uncertain. The name Lynn may signify a body of water near the town – the Welsh word llyn means a lake; but the name is plausibly of Anglo-Saxon origin, from lean meaning a tenure in fee or farm.[2] As the 1085 Domesday Book mentions saltings at Lena (Lynn), an area of partitioned pools may have existed there at the time. The presence of salt, which was relatively rare and expensive in the early Medieval period, may have added to the interest of Herbert de Losinga and other prominent Normans in the modest parish.

The town was named Len Episcopi (Bishop's Lynn) while under the temporal and spiritual jurisdiction of the Bishop of Norwich; but in the reign of Henry VIII it was surrendered to the crown and took the name of Lenne Regis or King's Lynn.[2] Domesday records it as Lun and Lenn, and ascribes it to the Bishop of Elmham and the Archbishop of Canterbury.[2]

The town is generally known locally as Lynn. The city of Lynn, Massachusetts, north of Boston, was named in 1637 in honour of its first official minister of religion, Samuel Whiting, who arrived there from Lynn, Norfolk.[3]

Middle Ages

Lynn originated on a constricted site south of where the River Great Ouse now discharges into the Wash. Development began in the early 10th century, but the place was not recorded until the early 11th century. Until the early 13th century, the Great Ouse emptied via the Wellstream at Wisbech. After its redirection, Lynn and its port gained significance and prosperity.[4]

In 1101, Bishop Herbert de Losinga of Thetford began to build the first medieval town between the rivers Purfleet to the north and Mill Fleet to the south. He commissioned St Margaret's Church and authorised a market to be held on Saturday.[5][6] Trade built up along the waterways that stretched inland; the town expanded between the two rivers.

Lynn's 12th-century Jewish community was exterminated during the widespread massacres of 1189.[7]

Early modern

During the 14th century, Lynn ranked as England's most important port. It was considered as vital to England in the Middle Ages as Liverpool was during the Industrial Revolution. Sea trade with Europe was dominated by the Hanseatic League of ports; the transatlantic trade and the rise of England's western ports did not begin until the 17th century. The Trinity Guildhall was rebuilt in 1421 after a fire. Walls entered by the South Gate and East Gate were erected to protect the town.[8] It retains two former Hanseatic League warehouses: Hanse House of 1475[9] and Marriott's Warehouse,in use between the 15th and 17th centuries.[10] These are the only remaining buildings of the Hanseatic League in England.

In the first decade of the 16th century, Thoresby College was built in Lynn by Thomas Thoresby to house priests of the Guild of The Holy Trinity. It had been incorporated in 1453 under a petition of its alderman, chaplain, four brethren and four sisters. These were licensed to found a chantry of chaplains for the altar of Holy Trinity in Wisbech; lands were granted in mortmain.[11] Lynn acquired a mayor and corporation in 1524. In 1537 the king took over the town from the bishop. In the same century the town's two annual fairs were reduced to one. In 1534 a grammar school was founded; four years later Henry VIII closed the Benedictine priory and the three friaries.

A piped water supply was created in the 16th century, although many could not afford to be connected: elm pipes carried water under the streets. King's Lynn suffered from outbreaks of plague, notably in 1516, 1587, 1597, 1636 and finally in 1665. Fire was another hazard – in 1572 thatched roofs were banned to reduce the risk. In the English Civil War, King's Lynn supported Parliament, but in August 1643 it was in Royalist hands. It changed sides again after Parliament sent an army and the town was besieged for three weeks.

A heart carved on the wall of the Tuesday Market Place marks the burning of an alleged witch, Margaret Read, in 1590. It is said that as she was burning her heart burst from her body and struck the wall.[12]

In 1683, the architect Henry Bell, once the town's mayor, designed the Custom House. He also designed the Duke's Head Inn, the North Runcton Church, and Stanhoe Hall, having gained inspiration while travelling in Europe as a young man.[13]

In the 16th and 17th centuries, the town's main export was grain. Lynn was no longer a major international port, but iron and timber were imported. King's Lynn suffered from the discovery of the Americas, which benefited ports on the west coast of England. It was also affected by the growth of London.

In the late 17th century, imports of wine from Spain, Portugal and France boomed, and there was still much coastal trade. It was cheaper to transport goods by water than by road at the time. Large amounts of coal arrived from the north-east of England.

The Fens began to be drained in the mid–17th century and the land turned to farming, allowing vast amounts of produce to be sent to London's growing market. Meanwhile, King's Lynn was still an important fishing port. Greenland Fishery House in Bridge Street was built in 1605. By the late 17th century shipbuilding and glass-making had developed.

In the early 18th century, Daniel Defoe called the town "beautiful, well built and well situated". Shipbuilding thrived, as did associated industries such as sail-making and rope-making. Glass-making prospered; brewing was another important industry. The first bank in King's Lynn opened in 1784.

A fearsome example of penal brutality occurred on 28 September 1708, when a seven-year-old boy, Michael Hammond, and his 11-year-old sister Ann were convicted of stealing a loaf of bread and sentenced to hanging. Their public executions took place near the South Gates. The Member of Parliament at the time was Sir Robert Walpole, generally regarded as the first Prime Minister of the United Kingdom.[14]

Modern

By the late 17th century, the town's decline was reversed by the somewhat late arrival of railway services in 1847, provided mainly by the Great Eastern Railway, subsequently the London and North Eastern Railway, running to Hunstanton, Dereham and Cambridge. The town was also served by the Midland and Great Northern Joint Railway (M&GN), which had offices at Austin Street, and a station at South Lynn (now dismantled). This was also its operational control centre until relocation to Melton Constable. The former M&GN lines across Norfolk were closed to passengers in February 1959.

The town's amenities continued to improve into the 20th century. A museum opened in 1904, and a public library in 1905. The first cinema, the Majestic, was officially opened on 23 May 1928. (The year is commemorated in a stained glass window on the front of the building.) The town council began a programme of regeneration in the 1930s.

During World War I, King's Lynn was one of the first towns in Britain to suffer aerial bombing. On the night of 19 January 1915, the town was bombed by a naval Zeppelin, L4 (LZ 27),[15] commanded by Captain Lieutenant Magnus von Platen-Hallermund. Eleven bombs were dropped, both incendiary and high explosive, doing extensive damage, killing two people in Bentinck Street, and injuring several others. When World War II began, it was assumed that King's Lynn would be safe from bombing, and many evacuees were sent from London but the town was not completely safe and suffered several raids.

In 1962, King's Lynn was designated an overflow town for London and its population increased. New estates were built at the Woottons and Gaywood. The town centre was redeveloped in the 1960s and many old buildings destroyed. Lynnsport, a sports centre, opened in 1982. The corn exchange was converted into a theatre in 1996.

The local breweries had closed by the 1950s, but new industries included food canning in the 1930s and soup-making in the 1950s. In the 1960s, the council tried to encourage development by building an industrial estate at Hardwick. The new industries that arrived included light engineering, clothing and chemicals and fishing remained important.

Recent changes

Since 2004, work has been under way to regenerate the town under a multi-million-pound scheme. The 1960s Vancouver Shopping Centre (now the Vancouver Quarter) was refurbished in 2005 under the scheme, but was expected to last only 25 years, according to the construction firm, even with a planned extension. An award-winning £6 million multi-storey car park was built.

To the south of town, residential housing appeared on a large area of brownfield land. Plans for another housing estate alongside the River Nar were opposed by local people and halted by the economic situation. There is also a business park, parkland, a school, shops and a new relief road in a £300 million plus scheme.

In 2006, King's Lynn became the United Kingdom's first member of The Hanse (Die Hanse), a network of towns and cities across Europe which historically belonged to the Hanseatic League. The league was an influential medieval trading association of merchant towns around the Baltic Sea and the North Sea, which contributed to Lynn's development.[16]

The Borough Council commissioned and accepted a 2008 report by DTZ. It dubbed King's Lynn's workforce as "low-value" with a "low skills base" and the town as having a "poor lifestyle offer". The quality of services and amenities was "unattractive to higher-value inward investors and professional employees with higher disposable incomes". Average earnings were well below regional and national levels, and many jobs in tourism, leisure and hotels were subject to seasonal fluctuations and likewise poorly paid. Education and workforce qualifications were described as below the national average. The borough ranked 150th out of 354 for deprivation.[17]

In 2009, a proposal was made for the Campbell's Meadow factory site to be redeveloped with a 5-hectare (12-acre) employment and business park. In June 2011 Tesco gained a permit for a superstore.[18] On 8 June 2010, it unveiled regeneration plans that would cost £32 million and were billed to create 900 jobs overall.[19] Tesco pledged £4 million of improvements in other areas of the town. Whilst it planned to spend £1.6 million widening Hardwick Road, the Sainsburys bid was preferred by the Council as offering the town more benefits.[19]

Sainsbury's £40 million plans for a superstore opposite Tesco on the Pinguin Foods site yielded an estimated 300 jobs. This was the key to securing the future of Pinguin Foods in King's Lynn.[20] Pinguin Foods released 12 acres (5 ha) of its 44-acre (18 ha) site to accommodate the proposed store. Mortson Assets' and Sainsbury's plan included creating a link road between Scania Way and Queen Elizabeth Way to improve access and allow the industrial estate to expand and attract new employers, while Sainsbury's maintains its store in the town centre. It has pledged £1.75 million for highways improvements and a further £7 million to invest in the Pinguin Foods factory.[19]

At 8 am on 15 January 2012, the landmark Campbell's Tower was demolished – a competition winner, Sarah Griffiths pulled the switch, whose father, Mick Locke, had died aged 52 after being scalded by steam at the factory in 1995. It was Campbell's first UK factory when it opened in the 1950s. At its peak in the early 1990s it employed over 700.[21]

A fire station was opened by HM The Queen in February 2015.[22]

Governance

King's Lynn became a municipal borough in 1883. The present Borough of King's Lynn and West Norfolk was an amalgamation of the Borough of King's Lynn, the urban districts of Downham Market and Hunstanton, and the rural districts of Docking, Downham, Freebridge Lynn, and Marshland.[23]

Heraldry

The shield in the coat of arms of King's Lynn and West Norfolk that of the ancient Borough of Lynn, recorded at the College of Arms in 1563. It shows the legend of Margaret of Antioch, who has appeared on Lynn shields since the 13th century, and to whom the parish church is dedicated.[23]

The per chevron division and addition of a bordure serve to distinguish the shield from its predecessor, while retaining its medieval simplicity. The bordure also suggests the wider bounds of the new authority, with the seven parts symbolising the seven amalgamated authorities.[23] The gull on the crest is a maritime reference. It has appeared as a supporter in some representations, but officially stands on a bollard to make it distinctive. It supports a crown or coronet like a King's Lynn supporter and a lion from the crest of Downham Market.

The coronet refers to the Borough's royal connections. The cross held by the gull is an extension of the two in the shield, and the cross in the coat of arms of Freebridge Lynn Rural District.[23]

The supporters are based on the crest of the Hunstanton Urban District Council. The lion is a variation of the lions, or leopards, in the Royal Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom and its fish tail suggests the borough's links with the sea.[23]

The fish–lion is also the centre feature in the borough's badge, but here it is surrounded by a garland of oakleaves as a reference to the rural nature of much of the district. Oak leaves are also a feature of the coronet in the crest of the former Downham Market Urban District Council.[23]

Geography

Topography

King's Lynn is the northernmost settlement on the River Great Ouse, lying 97 miles (156 km) north of London and 44 miles (71 km) west of Norwich.[2][26][27] The town lies about 5 miles (8 km) south of the Wash, a fourfold estuary subject to dangerous tides and shifting sandbanks, on the north-west margin of East Anglia. King's Lynn has an area of 11 square miles (28 km2).

The Great Ouse at Lynn is about 200 metres (660 ft) wide and the outfall for much of the Fens' drainage system. The much smaller Gaywood River also flows through the town, joining the Great Ouse at the southern end of South Quay close to the town centre.

A small part of the town, known as West Lynn, is on the west bank, and linked to the town centre by one of the oldest ferries in the country. Other districts of King's Lynn include the town centre, North Lynn, South Lynn, and Gaywood.

Climate

King's Lynn has a temperate oceanic climate (Köppen: Cfb). The annual mean daytime temperature is approximately 14 °C (57 °F). January is the coldest month with mean minimum temperatures between 0 to 1 °C (32.0 to 33.8 °F). July and August are the warmest months, with mean daily maximum temperatures of approximately 21 °C (70 °F).[28]

There are two Met Office weather stations close to King's Lynn: Terrington St Clement, about 4 miles (6 km) to the west and RAF Marham, about 10 miles (16 km) to the south east.

The absolute maximum temperature at Terrington stands at 35.1 °C (95.2 °F)[29] recorded in August 2003, though in a more average year the warmest day will only reach 29.4 °C (84.9 °F),[30] with 13.8 days[31] in total attaining a temperature of 25.1 °C (77.2 °F) or more. Typically all these figures are marginally lower than those for the southern half of the Fens due to the common presence of an onshore sea breeze, and occasional haar (cold sea fog), particularly in early summer and late spring. However, with a strong enough offshore breeze, the area can be notably warm. Terrington (along with Cambridge Botanical Gardens) achieved the national highest temperature of 2007, 30.1 °C (86.2 °F)[32]

The absolute minimum at Terrington is −15.4 °C (4.3 °F),[33] set in January 1979. A total of 41.6 nights will report an air frost at Terrington and 51.9 nights at Marham.

Annual rainfall totals 621 mm (24 in) at Marham, and 599 mm (24 in) at Terrington,[34] with 1 mm or more falling on 115 and 113 days,[35] respectively. All averages refer to the 30-year observation period 1971–2000.

| Climate data for Terrington St Clement | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 13.9 (57.0) |

17.4 (63.3) |

24.4 (75.9) |

25.3 (77.5) |

28.4 (83.1) |

32.4 (90.3) |

33.5 (92.3) |

35.1 (95.2) |

29.0 (84.2) |

25.0 (77.0) |

17.8 (64.0) |

16.4 (61.5) |

35.1 (95.2) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 6.5 (43.7) |

7.1 (44.8) |

10.0 (50.0) |

12.2 (54.0) |

15.9 (60.6) |

18.7 (65.7) |

21.5 (70.7) |

21.8 (71.2) |

18.4 (65.1) |

14.2 (57.6) |

9.5 (49.1) |

7.2 (45.0) |

13.6 (56.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 0.9 (33.6) |

1.0 (33.8) |

2.6 (36.7) |

3.9 (39.0) |

6.7 (44.1) |

9.5 (49.1) |

11.4 (52.5) |

11.4 (52.5) |

9.7 (49.5) |

6.8 (44.2) |

3.4 (38.1) |

1.8 (35.2) |

5.8 (42.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −15.4 (4.3) |

−12.8 (9.0) |

−8.3 (17.1) |

−5.4 (22.3) |

−4.2 (24.4) |

0.0 (32.0) |

2.7 (36.9) |

3.3 (37.9) |

— | −4.3 (24.3) |

−8.2 (17.2) |

−11.5 (11.3) |

−15.4 (4.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 54.65 (2.15) |

36.43 (1.43) |

46.75 (1.84) |

42.73 (1.68) |

47.97 (1.89) |

51.13 (2.01) |

45.73 (1.80) |

54.53 (2.15) |

53.51 (2.11) |

55.07 (2.17) |

57.86 (2.28) |

52.44 (2.06) |

598.79 (23.57) |

| Source: KNMI[36] | |||||||||||||

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average high °C (°F) | 6.6 (43.9) |

7.1 (44.8) |

10.0 (50.0) |

12.2 (54.0) |

16.2 (61.2) |

19.0 (66.2) |

21.7 (71.1) |

21.8 (71.2) |

18.6 (65.5) |

14.3 (57.7) |

9.7 (49.5) |

7.4 (45.3) |

13.8 (56.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 0.5 (32.9) |

0.6 (33.1) |

2.3 (36.1) |

4.0 (39.2) |

6.9 (44.4) |

9.7 (49.5) |

11.8 (53.2) |

11.8 (53.2) |

9.6 (49.3) |

6.6 (43.9) |

3.2 (37.8) |

1.6 (34.9) |

5.7 (42.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 54.7 (2.15) |

38.5 (1.52) |

49.5 (1.95) |

46.8 (1.84) |

48.1 (1.89) |

55.9 (2.20) |

44.1 (1.74) |

50.5 (1.99) |

54.9 (2.16) |

59.8 (2.35) |

63.3 (2.49) |

55.3 (2.18) |

621.3 (24.46) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 53.6 | 73.2 | 101.7 | 150.6 | 204.3 | 191.1 | 202.7 | 192.8 | 139.8 | 109.7 | 69.0 | 48.1 | 1,536.6 |

| Source: Met Office[37] | |||||||||||||

Parks

The largest of the town's several public parks are the Walks, a historic 17-hectare urban park in the centre of King's Lynn. The Walks are the only town walk in Norfolk to survive from the 18th century. The Heritage Lottery Fund donated £4.3 million towards their restoration, including the addition of modern amenities. They also include the Red Mount, a Grade II-listed 15th-century chapel. In 1998, the Walks were designated by English Heritage as a Grade II National historic park.

The Walks as a whole had a different and earlier origin, in that they were conceived not as a municipal park, as one understands the term today, but as a promenade for the citizens, away from the smell, grime and bustle of the town centre.[38] Harding's Pits form another public park, to the south of the town. This informal area of open space with large public sculptures was laid out to reflect the history of the town. Harding's Pits are managed by local volunteers under a management firm, which has successfully fought off the Borough Council's attempts to turn them into an attenuation drain.

Demography

In 2007, King's Lynn had a population of 42,800.[1] At Norfolk's 2007 census, King's Lynn, together with West Norfolk, had a population of 143,500, with an average population density of 1.0 persons per hectare.[1] For figures after 2011 see King's Lynn and West Norfolk.

Economy

King's Lynn has always been a centre for fishing and seafood (especially inshore prawns, shrimps and cockles). There have also been glass-making and small-scale engineering works (many fairground and steam engines were built here). It still contains much agricultural-related industry, including food processing. There are a number of chemical factories and the town retains a role as an import centre. In general, it is a regional centre for a still sparsely populated part of England.

King's Lynn was the fastest growing port in Great Britain in 2008. Department for Transport figures show that through-put increased by 33 per cent.[39]

In 2008, the German Palm Group began to erect one of the world's largest paper machines. This was constructed by Voith Paper. With a web speed of up to 2000 metres a minute and a web width of 10.63 metres, it can produce 400,000 metres a year of newsprint paper. The production is based on 100-per-cent recycled paper. The start-up was on 21 August 2009.[40]

The Port of King's Lynn has facilities for dry bulk cargo such as cereals and liquid bulk products such as petroleum products for Pace Petroleum. It also handles timber imported from Scandinavia and the Baltics and has large handling sheds for steel imports.[41]

Retail

King's Lynn is the primary retail centre in West Norfolk, also for people living outside the border of West Norfolk. The town centre is dominated by budget shops, reflecting the spending power of much of the population. The town centre fulfils a leisure role with entertainment centres, bars and restaurants, and has a range of service functions. There are around 5,300 retailing jobs.[42]

The town centre has 73,000 sq.m. of retail floor space in 347 shops, which exceeds the comparable centres of Bury St Edmunds and Boston. However, whilst the percentage of floor space in comparison shopping and that occupied by multiple retailers is above the national average, King's Lynn offers limited range of choice.[42]

Tourism

Tourism in King's Lynn is a minor industry, but attracts visitors to its historic centre. It acts as a base for visiting the Queen's home at Sandringham and other great country houses in the area. Within the town and across the nearby Fenland are some of the finest historic churches in Britain, built in a period when King's Lynn and its hinterland were very wealthy from trade and wool.

Transport

Major routes

The town is connected to the local cities of Norwich and Peterborough via the A47 and to Cambridge via the A10. It is also linked to Spalding and the North via the A17 and to other parts of Norfolk by the A148 and the A149

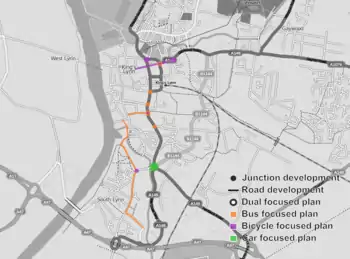

South Transport Project

A £7 million programme to redevelop the infrastructure of the town centre in the 2010s was largely provided by the Community Infrastructure Fund. The department programme is a collection of smaller developments, which are detailed below.[43]

Work on a cycle and bus route between the town centre and South Lynn began in June 2010 at a cost of £850,000. It runs 720 metres long, running from Morston Drift to Millfleet, with buses travelling in both directions and features a separate path for pedestrians and bicycles, which coincides with the bus route when crossing the Nar sluice. As part of the development, the Millfleet–St James' Road junction is being developed.[43]

A contraflow lane for bicycles was proposed, but not built along Norfolk Street from Albert Street to Blackfriars Road. This would have included a development of the Norfolk Road–Railway Road junction to better accommodate buses and bicycles. Similar work was to have taken place at the Norfolk Street–Littleport Street junction, so that buses would not get caught in the town-centre gyratory system.[43]

Bus priority measures have been added to four sets of traffic lights along St James' Road. This gives buses quicker access to the town centre and normalise journey times.[43]

Southgates Roundabout has been redeveloped. Many of its approach roads have been widened in the run up to the junction and the road markings redone in an attempt to improve lane discipline. Southgates Roundabout is a noted congestion hot spot.[43]

Other small developments are taking place to make junctions more car-friendly.[43]

Rail

King's Lynn railway station, the terminus of the Fen Line, is the only rail facility in King's Lynn. It provides services to Cambridge and London King's Cross. South Lynn railway station closed to passengers in 1959, as did Hunstanton in 1969.

West Norfolk Council are still ostensibly considering reopening a railway route between the King's Lynn railway station and the Hunstanton railway station. The possibility was proposed at a meeting of the council's Regeneration and Environment Panel on 29 October 2008. This had last been discussed in the 1990s. An environmental case was made for reviving the line to relieve road congestion.[44]

Buses

Nearly all Stagecoach services in the area have been withdrawn, leaving most services in King's Lynn operated by Lynx or Go To Town (West Norfolk Community Transport Project).

King's Lynn is also served by the excel bus route between Peterborough and Norwich, operated by First Eastern Counties. The Coasthopper route used to operate from King's Lynn around the Norfolk Coast, to Cromer, but since Stagecoach ceased its Norfolk operations, the western section of Coasthopper has been run by Lynx[45] rebranded as Coastliner 36, and extended inland from Wells-next-the-Sea to Fakenham. The section from Wells-next-the-Sea to Cromer is run by Sanders Coaches; this remains "Coasthopper" branded, but has been extended to inland North Walsham.[46]

Media

Newspapers

King's Lynn has two local newspapers: the twice-weekly Lynn News owned by Iliffe Media, and Your Local Paper, a free weekly.[47]

Magazines

KL magazine is a free lifestyle magazine that celebrates the best of west and north Norfolk. It has been published monthly since October 2010 and is distributed to local businesses across the region. It also issues special Food and Home Design & Build editions.[48]

Broadcasting

King's Lynn is served by BBC Radio Norfolk and Greatest Hits Radio West Norfolk, plus all national BBC radio stations. The local college runs a web-based TV station produced by its media students, entitled SpringboardTV.com, and holds an awards ceremony at the end of each academic year.

TV broadcasts are provided by BBC East, BBC Yorkshire and Lincolnshire, ITV Anglia, and ITV Yorkshire.

Education

King's Lynn has four secondary schools, three of which are in the town; King Edward VII School, the King's Lynn Academy, and Springwood High School. The fourth, St Clements High School, is in the nearby village of Terrington St Clement. The first is known, academically, for its physical education department. King's Lynn Academy is known for its maths and IT specialities, while Springwood specialises in performing arts and drama.[49][50][51] The nearest independent school is Wisbech Grammar School in Cambridgeshire.

The town contains a further education college, the College of West Anglia, founded in 1894 as the King's Lynn Technical School. In 1973, it was renamed the Norfolk College of Arts and Technology, and in 1998 merged with the Cambridgeshire College of Agriculture and Horticulture, which added campuses in Wisbech (now closed) and Milton, and changed its name to the College of West Anglia. In April 2006, the college merged with the Isle College in Wisbech, retaining the name College of West Anglia.[52]

Culture

St George's Guildhall

The Guild of St George was founded in 1376 and in 1406 acquired land for the Guildhall of St George, which was in use by 1428. The Guild performed plays in the Guildhall, the first known production being a nativity play in January 1445. This makes it the UK's oldest working theatre.

The Guildhall was used for meetings, dinners and performance until in 1547, when King Edward VI dissolved the Guilds. It then became the property of Lynn Corporation and known as the Common Town Hall. Research by the University of East Anglia confirms as probable the oral history of Kings Lynn that William Shakespeare performed in the Guildhall in 1593. This is the only still-working theatre in the world that can credibly claim to have hosted Shakespeare. In 1766 Guildhall shows were so popular that a new interior was built inside the present structure, probably on the earlier footprint. By 1945 the Guildhall was almost derelict and in danger of demolition. It was bought by Alexander Penrose, who gave it to the National Trust in 1951. The Pilgrim Trust, Arts Council and public subscription led to the Guildhall's conversion into an Arts Centre. Queen Elizabeth (the Queen Mother) opened the venue in July 1951 and launched the King's Lynn Festival.

Today the Guildhall is owned by the National Trust, leased by the Borough Council of King's Lynn and West Norfolk. Various groups are involved with the use of the building including Shakespeare's Guildhall Trust, King's Lynn Festival, King's Lynn Community Cinema Club

The Guildhall is managed by the Borough Council of King's Lynn and West Norfolk and is run as a venue for hire, supporting a year-round programme of theatre, dance, music, lectures and film. Shakespeare's Guildhall Trust have volunteers who open the theatre to visitors.

Arts

Ruth, Lady Fermoy, an accomplished concert pianist, moved to King's Lynn in 1931, as the bride of Lord Edmund Fermoy, who was to become the town mayor and the local MP. She demonstrated her affection for the town by organising concerts to give local people the chance to listen to professional music of the highest standard.[53]

In 1951, to complement the Festival of Britain, Lady Fermoy organised the King's Lynn Festival of the Arts. She was a close friend and lady-in-waiting to the Queen – later to become Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother – who agreed to become the festival's patron, and in July 1951 officially opened the restored St George's Guildhall. The Queen Mother was an enthusiastic and active supporter, who remained the festival's patron until her death in March 2002.[53]

Festival

The King's Lynn Festival, established in 1951, remains the premier music and arts festival in West Norfolk, attracting many visitors to the town each year for performances by internationally renowned artists. The festival is primarily known for its classical music programme, but also hosts jazz, choral, folk, opera, dance, films, talks and exhibitions, with dozens of fringe events each year.

Literature festivals

The King's Lynn Literature Festivals are held during a single weekend in March (fiction) and September (poetry) each year, usually in the town hall.[54]

Museums

Stories of Lynn Museum opened in March 2016, as part of the King's Lynn Town Hall complex. Set within the newly-revealed vaulted undercroft of the 15th-century Trinity Guildhall, Stories of Lynn presents the town's collection of objects and an extensive, nationally significant archive in an interactive and multi-media exhibition. True's Yard Fisherfolk Museum is a display of the social history of the North End fishermen, run by volunteers. It consists of a cottage and a smokehouse.[56] Since 2013, there has also been a local award-winning Military Museum, operated by The Bridge for Heroes Charity to raise funds.[57] Lynn Museum, run by Norfolk Museums Service, in Market Street, contains the local history of the town and the Bronze Age timber circle Seahenge.

Entertainment

Festival Too is held in Tuesday Market Place each summer. Performers have included Midge Ure, Deacon Blue, Suzi Quatro, 10cc, Mungo Jerry, the Human League, the Buzzcocks, M People, Atomic Kitten, Kieran Woodcock, S Club, and Beverley Knight.

The Majestic Cinema, in the town centre, is the town's only cinema.

King's Lynn's main venue for concerts, stand-up comedy shows and other live events is the Corn Exchange, in Tuesday Market Place. Many smaller venues such as Bar Red and the Wenns contribute to the local music scene, along with acts from other parts of the country.[58]

Mart

During the 16th century, King's Lynn's Tuesday Market Place hosted two important trade fairs, which attracted visitors from as far as Italy and Germany. As the importance of trade fairs declined, the Mart became a funfair, and was reduced to a single annual event that begins on 14 February (Valentine's Day) and lasts about a fortnight.

The Mart is also a memorial to the work of Frederick Savage, who worked in partnership with the Showmen's Guild of Great Britain to develop new funfair attractions.[59]

Sports

The town's football club is King's Lynn Town, which from the 2020–21 season plays in the National League. The club formed in 2010 after the original King's Lynn F.C. was wound up in December 2009. It plays its home games at the Walks Stadium in Tennyson Road, the home of the original King's Lynn FC.

King's Lynn has a speedway team, the King's Lynn Stars, which races at the Adrian Flux Arena in Saddlebow Road. The track has operated since 1965 on an open licence. It hosted Speedway-type events in the 1950s.

One of the town's basketball clubs, King's Lynn Fury, previously played in the National League out of Lynnsport, and represented the town in national competitions from 2004 to 2017. Lynn Nets, formed in 2008, also runs a programme in local competitions.

The historic hockey team The Pelicans, dating from 1920, currently plays at Lynnsport, having been based in nearby North Runcton until 1996.[60]

Notable people

- Nick Aldis (born 1986), wrestler known as Magnus etc., is billed as from King's Lynn.[61]

- Robert Armin (c. 1563–1615), actor with Lord Chamberlain's Men and writer, was born in Bishop's Lynn.[62]

- Thomas Baines (1820–1875), painter and explorer in Africa and Australia, was born in King's Lynn.[63]

- William Baly (1814–1861), physician extraordinary to Queen Victoria, was born and raised in King's Lynn.[64]

- Mrs. Bernard Beere (1851–1915), actress[65]

- Emily Bell (born 1965), journalist and academic, was born in King's Lynn.[66]

- Martin Brundle (born 1959), racing driver, was born in King's Lynn, as was his racing-driver son Alex in 1990.[67]

- Frederick Robert Buckley (1896–1976), author and broadcaster[68]

- Charles Burney (1726–1814), historian of music, served as organist of St Margaret's Church for nine years from 1751.[69]

- Charles Burney (1757–1817), scholar and bibliophile, was born in Lynn.[70]

- Frances Burney (1752–1840), novelist (Evelina etc.) and diarist, was born in Lynn.[71]

- Sarah Burney (1772–1844), novelist, was born in Lynn.[72]

- John Capgrave (1393–1464), prior, historian and theologian, was born and died in Bishop's Lynn.[73]

- Richard Carpenter (1929–2012), actor, screenwriter and author, was born in King's Lynn.[74]

- Gerry Conway (born 1947), percussionist with Cat Stevens etc., was born in King's Lynn.[75]

- G. G. Coulton (1858–1947), historian and controversialist, was born and partly educated in King's Lynn.[76]

- Samuel Gurney Cresswell (1827–1847), naval captain and Northwest Passage explorer, born and died in King's Lynn.[77]

- Joseph Dines (1886–1918), England amateur footballer and Olympic gold medallist (1912), born in King's Lynn.[78]

- Clara Dow (1883–1969), soprano in Gilbert and Sullivan operas, was born in King's Lynn.[79]

- Tim FitzHigham (born 1975) multi-award winning comedian, writer and record holder was born in King's Lynn[80]

- Charles Wycliffe Goodwin (1817–1878) Egyptologist, bible scholar and judge of British Supreme Court for China and Japan was born and raised in King's Lynn. (Brother of Harvey Goodwin)[81]

- Francis Goodwin (1784–1835), architect, was born in King's Lynn and kept a house there.[82]

- Harvey Goodwin (1818–1891), bishop and religious writer, born and raised in King's Lynn.[83]

- Florence Green (1901–2012), one of Britain's oldest people, British World War I veteran, moved to King's Lynn in 1920.[84]

- William Gurnall (1616–1679), author and clergyman[85]

- Ian Hamilton (1938–2001), poet and critic, was born in King's Lynn to Scottish parents.[86]

- Deaf Havana (formed 2005), English post-hardcore rock band, formed in King's Lynn.

- Charles Edward Hubbard (1900–1980), botanist specializing in grasses, attended King Edward VII Grammar School.[87]

- John Hullier (c. 1520–1556), Protestant martyr, was burnt at the stake for preaching in Lynn.[88]

- Jack Huston (born 1982), actor, appeared as Richard Harrow in Boardwalk Empire, in a supporting role in American Hustle, and as the eponymous lead in Ben-Hur (2016 film) historical drama.[89]

- Kathryn Johnson (born 1967), Olympic field hockey player, was born in King's Lynn.[90]

- Sir Benjamin Keene (1697–1757), diplomat successful in Spain, was born and educated in King's Lynn.[91]

- Margery Kempe (ca.1373–ca.1438) first autobiographer in English, born and probably died in Bishop's Lynn.[92]

- Anne Long (c. 1681–1711) friend of Jonathan Swift, fled from creditors to King's Lynn and died there.[93]

- George North (born 1992), Wales rugby union international, was born in King's Lynn.

- Barbara Parker (born 1982), Olympic track and field athlete, was born and educated in King's Lynn.[94]

- Lucy Pearson (born 1972), women's test cricketer and educationalist, was born in King's Lynn.[95]

- Ali Price (born 1993), Scotland Rugby Union player, born in King's Lynn.

- William Richards (1749–1818), Baptist minister, wrote a history of Lynn.[96]

- Edward Villiers Rippingille (c. 1790–1859), genre and portrait painter, was born in King's Lynn of farming parents.[97]

- Joan G. Robinson (1910–1988), children's writer, lived in King's Lynn with her writer husband Richard Gavin Robinson.[98]

- George Russell (born 1998), Formula One driver for Williams[99]

- Martin Saggers (born 1972), England cricketer and umpire, was born and raised in King's Lynn.[100]

- Hardiman Scott (1920–1999), journalist, broadcaster and novelist, was born in King's Lynn.[101]

- Helen Slatter (born 1970), Olympic swimmer, was born in King's Lynn.[90]

- Roger Taylor (born 1949) musician and drummer of Queen, born in King's Lynn.[102]

- Adam Thoroughgood (1604–1640), leading colonist in Virginia Colony, was born and raised in Lynn.

- Simon Thurley (born 1962), architectural historian and head of English Heritage, owns a second home in King's Lynn.[103]

- Gwladys Sutherst Townshend (1884–1959), Marchioness of Townshend, served as Mayor of King's Lynn in 1929.[104]

- George Vancouver (1757–1798), naval officer and explorer after whom Vancouver, BC, is named, was born in Lynn.[105]

- Lucy Verasamy (born 1980), TV weather forecaster, attended King Edward VII School.[106]

Location

In popular culture

Ruth Galloway, fictional heroine of Elly Griffiths' novels, is a forensic anthropologist living in a cottage near King's Lynn and teaching at the University of North Norfolk.[107]

Peter Grainger's DC Smith Investigation series of detective novels is set in "Kings Lake", a thinly-disguised analogue of King's Lynn.[108]

Media appearances

King's Lynn and surrounding villages have since the early 20th century been popular with film and later TV producers. Due to its architecture and landscape, the area often stands in for other parts of the world, notably the Netherlands and France. The town appeared as the Netherlands in The Silver Fleet (1943) and One of Aircraft Is Missing (1942), and Germany in Operation Crossbow in 1965. It appeared as France in 'Allo 'Allo!, the long-running BBC comedy, and nearby Fenland villages appeared as France in Joe Wright's Atonement. The nearby sandpit at Bawsey/Leziate appeared as the Sudan in the BBC series, Dad's Army, while flashback sequences of Corporal Jones's war recollections were cited here in the episode "Two and a Half Feathers", which drew on the classic 1902 A. E. W. Mason novel The Four Feathers. The sequences integrated footage from the 1939 Alexander Korda film production and dramatic music from the DeWolfe music library.

The town served as an earlier Dutch New York in the 1985 feature film Revolution. Produced by the British production company Goldcrest and starring Al Pacino, it was a box-office disaster. Many locals were used as extras. The BBC series Lovejoy also used the town, as did the Anglia Television series Tales Of The Unexpected and the Granada series Sherlock Holmes, starring Jeremy Brett in the title role. The last had King's Lynn as the Limehouse area of London, with old back streets and listed buildings appearing as an opium den. The recognisable Town Hall, with its flint-coated front, appeared near the beginning of the episode, which was called The Man With the Twisted Lip.

In the early 2000s, the BBC used the town bus station, local roads and the nearby Royal estate of Sandringham in the comedy drama series Grass, featuring Simon Day. It has in the last few years appeared many times on programmes such as the BBC's Antiques Road Trip, Flog It!, and a BBC Four documentary 'The Last Journey of the Magna Carta King' following the trail of John, King of England and how he lost his treasure in the Wash.[109] The nearby village of Castle Rising appeared in the 1980s Oscar-winning feature 'Out Of Africa' as a Danish port.

Further reading

ed by Susan Yaxley (2009). The Siege of King's Lynn. Larks Press. ISBN 9780948400209.

References

- "Can Overview of King's Lynn and West Norfolk – Part 1" (PDF). 2007. pp. 2, 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 June 2010. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- Lewis, Samuel (1848). "Lynn, or Lynn-Regis". A Topographical Dictionary of England. pp. 203–208.

- "Brief History of Lynn". Ci.lynn.ma.us. 30 May 1912. Archived from the original on 29 August 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- "History of Lynn" Volume 1 by William Richards M.A. 1812

- Lambert, Tim. "A history of King's Lynn". Retrieved 2 June 2010.

- "History and Heritage of King's Lynn". Borough Council of King's Lynn & West Norfolk. Archived from the original on 7 May 2010. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- "The Jewish Community of King's Lynn". The Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- "King's Lynn". Poppyland Publishing. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- Historic England. "Hanse House (1195393)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- Historic England. "Marriott's Warehouse (1212000)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- Pugh, R. B. (2002). "Guild of the Holy Trinity". A History of the County of Cambridge and the Isle of Ely: Volume 4: City of Ely; Ely, N. and S. Witchford and Wisbech Hundreds. pp. 255–256.

- Castelow, Ellen. "The history of witches in Britain". Historic UK. Retrieved 22 August 2014.

- "Custom House, King's Lynn". Eastern Daily Press. Archived from the original on 9 July 2010. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- "18 December 1969, Death penalty abolished". 1 April 2007. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- "Zeppelin L4 (LZ–27) crashed at Denmark, fuel shortage | eZEP-blog". Blog.ezep.de. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- "King's Lynn, a Hanse League Member". King's Lynn and West Norfolk Borough Council Website. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 15 January 2007.

- "Economic Impact Assessment of King's Lynn Marina" (PDF). June 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- "Welcome to Campbells Meadow". Tesco. 2009. Archived from the original on 23 January 2010. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- "Supermarket giants battle it out for Hardwick contract". Lynn News. 8 June 2010. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- "A New Sainsbury's for King's Lynn". Sainsbury's. 2009. Archived from the original on 3 March 2009. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- "Video: Thousands gather to watch Campbell's tower demolished in King's Lynn – News – Eastern Daily Press". Edp24.co.uk. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- Winchester, Levi (2 February 2015). "Queen and Duke of Edinburgh brave the cold to open new fire station in King's Lynn". Daily Express.

- "King's Lynn and West Norfolk County Council". Civic Heraldry. Archived from the original on 28 August 2009. Retrieved 27 May 2010.

- "Stadt Emmerich am Rhein". Emmerich am Rhein. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- OS Explorer Map 250 – Norfolk Coast West. Ordnance Survey. 2002. ISBN 0-319-21886-4.

- OS Explorer Map 236 – King's Lynn, Downham Market & Swaffham. Ordnance Survey. 1999. ISBN 0-319-21867-8.

- "Met Office: Climate averages 1971–2000". Met Office. 2000. Archived from the original on 2 March 2014. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- "2003 maximum". Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- "1971-00 average warmest day". Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- "1971-00 >25c days". Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- "2007 maximum". Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- "1979 minimum". Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- "average rainfall". Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- "average rain days". Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- "Climate Normals 1971–2000". KNMI. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- "Marham 1971–2000 climate averages". Met Office. Retrieved 1 July 2010.

- "The Walks". King's Lynn Online. Archived from the original on 18 May 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- "King's Lynn is fastest growing port in Britain". Business Weekly. 4 November 2009. Retrieved 7 July 2014.

- "Standorte – King's Lynn – English". The Palm Group. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- "Port of Kings Lynn: Commodities". Associated British Ports. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- "The Vision for King's Lynn 2000–2023" (PDF). April 2004. pp. 2, 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2010.

- "King's Lynn South Transport Major Scheme" (PDF). Retrieved 17 November 2009.

- "Lynn-Hunstanton rail line re-opening hope revived". Lynn News. 29 October 2008. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- http://www.lynxbus.co.uk/news/service-changes–28th-april/

- "Lynn News". Retrieved 27 May 2010.

- "KL magazine". Retrieved 27 May 2010.

- "King Edward VII School". Archived from the original on 22 May 2010. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- "The Park High School". Archived from the original on 22 May 2010. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- "Springwood High School". springwood.norfolk.sch.uk. Archived from the original on 8 June 2010. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- "History of College". College of West Anglia. Archived from the original on 28 March 2010. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- "History of the King's Lynn Festival". kingslynnfestival.org.uk. Archived from the original on 3 November 2014. Retrieved 8 July 2014.

- "Fleur Adcock, David Harsent Katy Evans-Bush, Matthew Caley Martin Figura, Heidi Williamson Tim Liardet, Peter Scupham Christopher Reid, John Hartley Williams Estonian poet Kristiina Ehin and from Germany, Ludwig Steinherr". Lynnlitfests.com. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- "Hanseatic League" (PDF). www.u3asutes.org.uk. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- Museum site: Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- Charity site. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- "Kings Lynn Corn Exchange". Kings Lynn Corn Exchange. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- "King's Lynn History". Borough Council of King's Lynn and West Norfolk. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- "history of Pelicans Hockey Club". Archived from the original on 29 October 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- Retrieved 23 March 2014.Archived 12 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ODNB: Martin Butler, "Armin, Robert (1563–1615)" Retrieved 23 March 2014, pay-walled.

- ODNB: Elizabeth Baigent, "Baines, (John) Thomas (1820–1875)" Retrieved 23 March 2014, pay-walled.

- ODNB: Bill Forsythe, "Baly, William (1814–1861)" Retrieved 24 March 2014, pay-walled.

- Free BMD, volume 13, p. 183.

- Debretts. Retrieved 24 March 2014. Archived 27 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine; citation still needed for King's Lynn birth.

- "Martin Brundle | | F1 Driver Profile | ESPN F1". En.espnf1.com. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- Alison Gifford, KL Magazine, October 2016 The Perfect Local Ghost Story For Halloween pp. 22–24.

- ODNB: John Wagstaff, "Burney, Charles (1726–1814)" Retrieved 23 March 2014, pay-walled.

- ODNB: Lars Troide, "Burney, Charles (1757–1817)" Retrieved 23 March 2014, pay-walled.

- ODNB: Pat Rogers, "Burney, Frances (1752–1840)" Retrieved 22 March 2014, pay-walled.

- ODNB: Lorna J. Clark, "Burney, Sarah Harriet (1772–1844)" Retrieved 22 March 2014, pay-walled.

- ODNB: Peter J. Lucas, "Capgrave, John (1393–1464)" Retrieved 22 March 2014, pay-walled.

- Obituary. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Citation required.

- ODNB: Henry Summerson, "Coulton, George Gordon (1858–1947)" Retrieved 24 March 2014, pay-walled.

- Toronto Library. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- LFC History Net Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- Francis Espinasse, "Goodwin, Charles Wycliffe (1817–1878)", rev. Josef L. Altholz Retrieved 23 March 2014, pay-walled.

- ODNB: M. H. Port, "Goodwin, Francis (1784–1835)" Retrieved 24 March 2014, pay-walled.

- ODNB: P. C. Hammond, "Goodwin, Harvey (1818–1891)" Retrieved 23 March 2014, pay-walled.

- Britten, Nick (16 January 2010). "108-year-old woman emerges as Britain's oldest first World War veteran". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- "Gurnall, William (GNL632W)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ODNB: Karl Miller, "Hamilton, (Robert) Ian (1938–2001)" Retrieved 23 March 2014, pay-walled.

- Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- Foxe's Book of Martyrs No. 337. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- Jack Huston

- SR Olympic Sports. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- ODNB: M. J. Mercer, "Keene, Sir Benjamin (1697–1757)" Retrieved 24 March 2014, pay-walled.

- ODNB: Felicity Riddy, "Kempe, Margery (c. 1373 – in or after 1438)" Retrieved 23 March 2014, pay-walled.

- J. Swift: Journal to Stella, ed. H. Williams (1948), Vol. I, pp. 118–119.

- College of West Anglia Hall of Fame. Retrieved 24 April 2014. Archived 2 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- CricInfo profile. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- ODNB: J. A. Oddy, "Richards, William (1749–1818)", Retrieved 24 March 2014, pay-walled.

- ODNB: Francis Greenacre, "Rippingille, Edward Villiers (c. 1790–1859)" Retrieved 24 March 2014, pay-walled.

- Kirkpatrick, D. L., ed. (1978). Twentieth-Century Children's Writers. New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 1066–1068. ISBN 0-312-82413-0.

- "About George Russell". georgerussellracing.com. George Russell. Archived from the original on 15 December 2014. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

- ESPN Cricinfo Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- Obituary. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- Official website. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- "Lady Mayor of Lynn" Boston Sunday Globe (26 May 1929): B3. ProQuest 758624515

- ODNB: Andrew C. F. David, "Vancouver, George (1757–1798)" Received 23 March 2014, pay-walled.

- Extreme Phone Calls Pilot Geography Blog: Weather, Geography Department, King Edward School, 12 May 2006.

- "Ruth Galloway". Elly Griffiths' official website. Archived from the original on 3 May 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- "DC Smith Series". Goodreads.

- The Last Journey of the Magna Carta King (Television production). BBC. 9 February 2015.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for King's Lynn. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to King's Lynn. |