Baffin Island

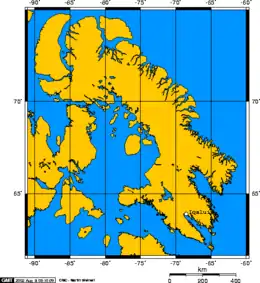

Baffin Island (Inuktitut: ᕿᑭᖅᑖᓗᒃ, Qikiqtaaluk IPA: [qikiqtaːluk], French: Île de Baffin, Terre de Baffin, formerly Baffin Land),[3] in the Canadian territory of Nunavut, is the largest island in Canada and the fifth-largest island in the world. Its area is 507,451 km2 (195,928 sq mi) and its population was 13,148 as of the 2016 Canadian Census. It is located in the region of 70° N and 75° W.[4]

| Native name: ᕿᑭᖅᑖᓗᒃ (Qikiqtaaluk) | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

Baffin Island  Baffin Island | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Northern Canada |

| Coordinates | 68°N 70°W |

| Archipelago | Arctic Archipelago |

| Area | 507,451 km2 (195,928 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 5th |

| Highest elevation | 2,147 m (7044 ft) |

| Highest point | Mount Odin |

| Administration | |

Canada | |

| Territory | Nunavut |

| Largest settlement | Iqaluit (pop. 7,740) |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 13,148[1] (2016) |

| Pop. density | 0.02/km2 (0.05/sq mi) |

| Ethnic groups | Inuit (72.7%), non-Aboriginal (25.3%), First Nations (0.7%), Métis (0.5%)[2] |

It was named by English colonists after English explorer William Baffin.[4]

Geography

Iqaluit, the capital of Nunavut, is located on the southeastern coast. Until 1987, the town was called Frobisher Bay, after the English name for the bay on which it is located, named for Martin Frobisher. That year the community voted to restore the Inuktitut name.[5]

To the south lies Hudson Strait, separating Baffin Island from mainland Quebec.[6] South of the western end of the island is the Fury and Hecla Strait,[7] which separates the island from the Melville Peninsula[8] on the mainland. To the east are Davis Strait[9] and Baffin Bay,[10] with Greenland beyond.[6] The Foxe Basin,[11] the Gulf of Boothia[12] and Lancaster Sound[13] separate Baffin Island from the rest of the Arctic Archipelago to the west and north.

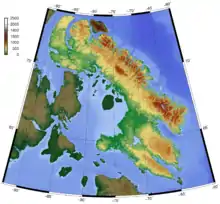

The Baffin Mountains run along the northeastern coast of the island and are a part of the Arctic Cordillera. The highest peak is Mount Odin, with an elevation of at least 2,143 m (7,031 ft), although some sources say 2,147 m (7,044 ft).[14][15] Another peak of note is Mount Asgard, located in Auyuittuq National Park, with an elevation of 2,011 m (6,598 ft). Mount Thor, with an elevation of 1,675 m (5,495 ft), is said to have the greatest purely vertical drop (a sheer cliff face) of any mountain on Earth, at 1,250 m (4,100 ft).[16] Mount Sharat,[17] with an elevation of 422 m (1,385 ft) and a prominence of 67 m (220 ft) is located on Baffin Island. The mountain is named after geologist Sarat Kumar Rai, the chief geology curator in the Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago. Rai or Roy, a native of India, studied in India, London, and earned his Ph.D. at the University of Chicago. Shortly after he started at the Field Museum he joined the 1927-1928 Rawson-Macmillan Expedition to Baffin Island and Labrador. This 15-month expedition began in June 1927.

The two largest lakes on the island lie in the south-central part of the island: Nettilling Lake (5,542 km2 [2,140 sq mi]) and Amadjuak Lake (3,115 km2 [1,203 sq mi]) further south.[18][19][20]

The Barnes Ice Cap, in the middle of the island, has been retreating since at least the early 1960s, when the Geographical Branch of the then Department of Mines and Technical Surveys sent a three-man survey team to the area to measure isostatic rebound and cross-valley features of the Isortoq River.[21] Conversely, in the 1970s parts of Baffin Island failed to have the usual ice-free period in the summer.[22]

History

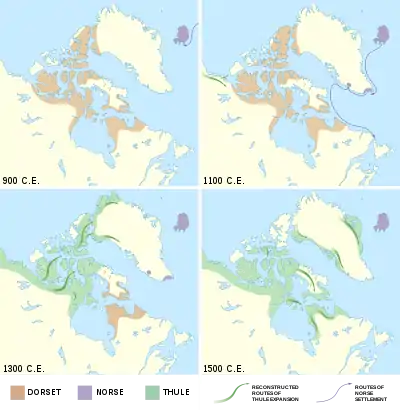

Baffin Island has been inhabited for over 3,000 years, first by the pre-Dorset, followed by the Dorset, and then by the Thule people, ancestors of the Inuit, who have lived on the island for the last thousand years.[23][24] In about 986, Erik Thorvaldsson, known as Erik the Red,[25] formed three settlements near the southwestern tip of Greenland.[26] In late 985 or 986, Bjarni Herjólfsson, sailing from Iceland to Greenland, was blown off course and sighted land southwest of Greenland. Bjarni appears to be the first European to see Baffin Island, and the first European to see North America beyond Greenland.[25] It was about 15 years later that the Norse Greenlanders, led by Leif Erikson, a son of Erik the Red, started exploring new areas around the year 1000.[25] Baffin Island is thought to be Helluland, and the archaeological site at Tanfield Valley is thought to have been a trading post.[27][28] The Saga of Erik the Red, 1880 translation into English by J. Sephton from the original Icelandic 'Eiríks saga rauða':

They sailed away from land; then to the Vestribygd and to Bjarneyjar (the Bear Islands). Thence they sailed away from Bjarneyjar with northerly winds. They were out at sea two half-days. Then they came to land, and rowed along it in boats, and explored it, and found there flat stones, many and so great that two men might well lie on them stretched on their backs with heel to heel. Polar-foxes were there in abundance. This land they gave name to, and called it Helluland (stone-land).[27]

In September 2008, the Nunatsiaq News, a weekly newspaper, reported that Patricia Sutherland, who worked at the Canadian Museum of Civilization, had archaeological remains of yarn and cordage [string], rat droppings, tally sticks, a carved wooden Dorset culture face mask depicting Caucasian features, and possible architectural remains, which indicated that European traders and possibly settlers had been on Baffin Island not later than 1000 CE.[29] What the source of this Old World contact may have been is unclear and controversial;[24][30][31][32][33] the newspaper article states:

Dating of some yarn and other artifacts, presumed to be left by Vikings on Baffin Island, have produced an age that predates the Vikings by several hundred years. So, as Sutherland said, if you believe that spinning was not an indigenous technique that was used in Arctic North America, then you have to consider the possibility that as "remote as it may seem," these finds may represent evidence of contact with Europeans prior to the Vikings' arrival in Greenland.[29]

Sutherland's research eventually led to a 2012 announcement that whetstones had been found with remnants of alloys indicative of Viking presence.[34] In 2018, Michele Hayeur Smith of Brown University, who specializes in the study of ancient textiles, wrote that she does not think the ancient Arctic people, the Dorset and Thule, needed to be taught how to spin yarn: "It's a pretty intuitive thing to do."[24]

...the date received on Sample 4440b from Nanook clearly indicates that sinew was being spun and plied at least as early, if not earlier, than yarn at this site. We feel that the most parsimonious explanation of this data is that the practice of spinning hair and wool into plied yarn most likely developed naturally within this context of complex, indigenous, Arctic fiber technologies, and not through contact with European textile producers. [...] Our investigations indicate that Paleoeskimo (Dorset) communities on Baffin Island spun threads from the hair and also from the sinews of native terrestrial grazing animals, most likely musk ox and arctic hare, throughout the Middle Dorset period and for at least a millennium before there is any reasonable evidence of European activity in the islands of the North Atlantic or in the North American Arctic.

A long-running debate disputes whether the Vikings taught indigenous peoples in the Canadian Arctic how to spin yarn when the invaders arrived in the region around 1,000 years ago. The team found that some of the spun yarn dates back at least 2,000 years, long before the Vikings arrived in the area. This shows that the indigenous peoples in the Canadian Arctic developed yarn-spinning technologies without any help from the Vikings, the scientists said.

William W. Fitzhugh, Director of the Arctic Studies Center at the Smithsonian Institution, and a Senior Scientist at the National Museum of Natural History, wrote that there is insufficient published evidence to support Sutherland's claims, and that the Dorset were using spun cordage by the 6th century.[35] In 1992, Elizabeth Wayland Barber wrote that a piece of three-ply yarn that dates to the Paleolithic era, that ended about 10,000 BP, was found at the Lascaux caves in France. This yarn consisted of three s-twist strands that were z-plied, much like the way a three-ply yarn is made now, the Baffin Island yarn was a simple two-ply yarn.[31] The eight sod buildings and artifacts found in the 1960s at L'Anse aux Meadows, located on the northern tip of Newfoundland Island, remains the only confirmed Norse site in North America outside of those found in Greenland.[36]

Administration

Baffin Island is part of the Qikiqtaaluk Region.

Communities by population

| City or hamlet | 2016[37] | 2011[37] | 2006[38] | 2001[38] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iqaluit | 7,740 | 6,699 | 6,184 | 5,236 |

| Pond Inlet | 1,617 | 1,549 | 1,315 | 1,220 |

| Pangnirtung | 1,481 | 1,425 | 1,325 | 1,276 |

| Kinngait | 1,441 | 1,363 | 1,236 | 1,148 |

| Clyde River | 1,053 | 934 | 820 | 785 |

| Arctic Bay | 868 | 823 | 690 | 646 |

| Qikiqtarjuaq | 598 | 520 | 473 | 519 |

| Kimmirut | 389 | 455 | 411 | 433 |

| Nanisivik | 0 | 0 | 0 | 77 |

The hamlets of Kinngait and Qikiqtarjuaq do not lie on Baffin Island proper. Kinngait is situated on Dorset Island, which is located a few kilometres from the south eastern tip of the Foxe Peninsula. Similarly, Qikiqtarjuaq is situated on Broughton Island, which is located near the northern coast of the Cumberland Peninsula.

The Mary River Mine, an iron ore mine with an estimated 21-year life, at Mary River, may include building a railway and a port to transport the ore.[39] This may create a temporary mining community there.

Wildlife

Baffin Island has both year-round and summer visitor wildlife. On land, examples of year-round wildlife are barren-ground caribou, polar bear, Arctic fox, Arctic hare, lemming and Arctic wolf.

Barren-ground caribou herds migrate in a limited range from northern Baffin Island down to the southern part in winter, even to the Frobisher Bay peninsula, next to Resolution Island, then migrating back north in the summer. In 2012, a survey of caribou herds found that the local population was only about 5,000, a decrease of as much as 95% from the 1990s.[40]

Arctic hares are found throughout Baffin Island. Their fur is pure white in winter and moults to a scruffy dark grey in summer. Arctic hares and lemmings are a primary food source for Arctic foxes and Arctic wolves.[41]

Lemmings are also found throughout the island and are a major food source for Arctic foxes, Arctic wolves and the snowy owl. In the winter, lemmings dig complicated tunnel systems through the snow drifts to get to their food supply of dry grasses and lichens.[42]

Predators

Polar bears can be found all along the coast of Baffin Island but are most prevalent where the sea ice takes the form of pack ice, where their major food sources—ringed seals (jar seal) and bearded seals—live. Polar bears mate approximately every year, bearing one to three cubs around March. Female polar bears may travel 10–20 km (6–12 mi) inland to find a large snow bank where they dig a den in which to spend the winter and later give birth. The polar bear population here is one of 19 genetically distinct demes of the circumpolar region.[43]

Arctic foxes can usually be found where polar bears venture on the fast ice close to land in their search for seals. Arctic foxes are scavengers and often follow polar bears to get their leavings. On Baffin Island, Arctic foxes are sometimes trapped by Inuit, but there is no longer a robust fur industry.

The Arctic wolf and the Baffin Island wolf, a grey wolf subspecies, are also year-round residents of Baffin Island. Unlike the grey wolf in southern climes, Arctic wolves often do not hunt in packs, although a male-female pair may hunt together.

Birds

Nesting birds are summer land visitors to Baffin Island. Baffin Island is one of the major nesting destinations from the Eastern and Mid-West flyways for many species of migrating birds. Waterfowl include Canada goose, snow goose and brant goose (brent goose). Shore birds include the phalarope, various waders (commonly called sandpipers), murres including Brünnich's guillemot, and plovers. Three gull species also nest on Baffin Island: glaucous gull, herring gull and ivory gull.

Long-range travellers include the Arctic tern, which migrates from Antarctica every spring. The varieties of water birds that nest here include coots, loons, mallards, and many other duck species.

Marine mammals

In the water (and under the ice), the main year-round species is the ringed seal. It lives offshore within 8 km (5 mi) of land. In winter, it makes a number of breathing holes in the ice, up to 2.4 m (8 ft) thick. It visits each one often to keep the hole open and free from ice. In March, when a female is ready to whelp, she will enlarge one of the breathing holes that has snow over it, creating a small "igloo" where she whelps one or two pups. Within three weeks the pups are in the water and swimming. In summer, ringed seals keep to a narrow territory about 3 km (2 mi) along the shoreline. If pack ice moves in, they may venture out 4–10 km (2–6 mi) and follow the pack ice, dragging themselves up on an ice floe to take advantage of the sun.

Summer visitors

Water species that visit Baffin Island in the summer are:

Harp seals (or saddle-backed seals), which migrate from major breeding grounds off the coast of Labrador and the southeast coast of Greenland to Baffin Island for the summer.[44] Migrating at speeds of 15–20 km/h (9–12 mph), they all come up to breathe at the same time, then dive and swim up to 1–2 km (0.62–1.24 mi) before surfacing again. They migrate in large pods consisting of a hundred or more seals to within 1–8 km (0.62–4.97 mi) of the shoreline, which they then follow, feeding on crustaceans and fish.

Walruses, which do not migrate far off land in the winter. They merely follow the "fast ice", or ice that is solidly attached to land, and stay ahead of it as the ice hardens further and further out to sea. As winter progresses, they will always remain where there is open water free of ice. When the ice melts, they move in to land and can be found basking on rocks close to shore. One of the largest walrus herds can be found in the Foxe Basin on the western side of Baffin Island. [45]

Beluga or white whales migrate along the coast of Baffin Island; some head north to the feeding grounds in the Davis Strait between Greenland and Baffin Island, or into the Hudson Strait or any of the bays and estuaries in between. Usually travelling in pods of two or more, they can often be found very close to shore (100 m [330 ft] or less). They come up to breathe every 30 seconds or so as they make their way along the coastline eating crustaceans.

Narwhals, which are known for the males' long, spiralling single tusk, can also be found along the coast of Baffin Island in the summer. Much like their beluga cousins, they may be found in pairs or even in a large pod of ten or more males, females and newborns. They also can be often found close to the shoreline, gracefully pointing their tusks skyward as they come up for air. When they first arrive, the males arrive a few weeks ahead of the females and young.

The largest summer visitor to Baffin Island is the bowhead whale. Found throughout the Arctic range, one group of bowhead whales is known to migrate to the Foxe Basin, a bay on the western side of Baffin Island. It is still not known whether they visit for the lush sea bounty or to calve in the Foxe Basin.

Climate

Baffin Island lies in the path of a generally northerly airflow all year round, so, like much of northeastern Canada, it has an extremely cold climate. This brings very long, cold winters and foggy, cloudy summers, which have helped to add to the remoteness of the island. Spring thaw arrives much later than normal for a position straddling the Arctic Circle: around early June at Iqaluit in the south-east but around early- to mid-July on the north coast where glaciers run right down to sea level. Snow, even heavy snow, can occur at any time of the year, although it is least likely in July and early August. Average annual temperatures at Iqaluit are around −9.5 °C (14.9 °F), compared with around 5 °C (41 °F) in Reykjavík,[maps 1] which is at a similar latitude.[46]

Sea ice surrounds the island for most of the year and only disappears completely from the north coast for short, unpredictable periods from mid- to late June until the end of September.

Most of Baffin Island lies north of the Arctic Circle—all communities from Pangnirtung northwards have polar night in winter and midnight sun in summer. The eastern community of Clyde River has twilight instead of night from April 26 until May 13, continuous sunlight for 2½ months from May 14 to July 28, then twilight instead of night from July 29 until August 16. This gives the community just over 3½ months without true night. In the winter, the sun sets on November 22 and does not rise again until January 19 of the next year. Pond Inlet has civil twilight from December 16 to December 26. However, there is twilight for at least 4 hours per day, unlike places such as Eureka.

Economic resources

The Hall Peninsula of southern Baffin Island includes the Chidliak Kimberlite Province, which had been found to include diamond-bearing kimberlite pipes.[47]

Baffin Island in popular culture

The popular British band Radio Stars wrote and recorded a song extolling the delights of Baffin Island, entitled 'Baffin Island', on their second album 'Holiday Album' in 1978, released on Chiswick Records. The song discussed the possibilities of retreating to Baffin Island in times of nuclear war or other devastation, given its remoteness and size.

See also

References

Notes

- Does not include Kinngait (1,441) and Qikiqtarjuaq (598). Both of which do not lie on Baffin Island proper

- 2006 Aboriginal Population Profile for Nunavut communities.

- Baffin Island / Île de Baffin (Formerly Baffin Land)

- Quinn, Joyce A.; Woodward, Susan L. (January 31, 2015). Earth's Landscape: An Encyclopedia of the World's Geographic Features. ABC-CLIO. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-61069-446-9.

- "About Iqaluit: History & Milestones". Archived from the original on April 19, 2019.

- "The Atlas of Canada - Search". archive.is. January 1, 2013. Archived from the original on January 1, 2013.

- "Fury and Hecla Strait". Archived from the original on October 2, 2012. Retrieved October 13, 2012.

- "The Atlas of Canada - Search". archive.is. January 1, 2013. Archived from the original on January 1, 2013.

- "The Atlas of Canada - Search". archive.is. January 1, 2013. Archived from the original on January 1, 2013.

- Baffin Bay Archived 2012-10-06 at the Wayback Machine with Greenland to the east

- "The Atlas of Canada - Search". archive.is. January 1, 2013. Archived from the original on January 1, 2013.

- "The Atlas of Canada - Search". archive.is. January 1, 2013. Archived from the original on January 1, 2013.

- "The Atlas of Canada - Search". archive.is. January 1, 2013. Archived from the original on January 1, 2013.

- "Mount Odin, Nunavut". Peakbagger.com.

- "Mount Odin at the Atlas of Canada".

- "Mount Thor -The Greatest Vertical Drop on Earth!". November 19, 2012.

- Mount Sharat

- "Nunavut – Lake Areas and Elevation (lakes larger than 400 square kilometres)".

- "The Atlas of Canada - Search". archive.is. January 1, 2013. Archived from the original on January 1, 2013.

- "The Atlas of Canada - Search". archive.is. January 1, 2013. Archived from the original on January 1, 2013.

- Jacobs, John D.; et al. (May 3, 2018). "Recent Changes at the Northwest Margin of the Barnes Ice Cap, Baffin Island, N.W.T., Canada". Arctic and Alpine Research. 25 (4): 341–352. doi:10.1080/00040851.1993.12003020 (inactive January 16, 2021). ISSN 0004-0851.CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2021 (link)

- Cora Cheney, Crown of The World, Dodd, Merad, and Company, New York, 1979.

- S. Brooke; R. Park (2016). "Pre-Dorset Culture". In M. Friesen; O. Mason (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the Prehistoric Arctic. 1. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199766956.013.39.

- Weber, Bob (July 22, 2018). "Ancient Arctic people may have known how to spin yarn long before Vikings arrived". Old theories being questioned in light of carbon-dated yarn samples. CBC. Retrieved January 2, 2019.

… Michele Hayeur Smith of Brown University in Rhode Island, lead author of a recent paper in the Journal of Archaeological Science. Hayeur Smith and her colleagues were looking at scraps of yarn, perhaps used to hang amulets or decorate clothing, from ancient sites on Baffin Island and the Ungava Peninsula. The idea that you would have to learn to spin something from another culture was a bit ludicrous," she said. "It's a pretty intuitive thing to do.

- Wallace, Birgitta (2003). "The Norse in Newfoundland: L'Anse aux Meadows and Vinland". The New Early Modern Newfoundland. 19 (1).

- The Fate of Greenland's Vikings, by Dale Mackenzie Brown, Archaeological Institute of America, 28 February 2000

- "The Saga of Erik the Red". The Icelandic Saga Database. Sveinbjörn Þórðarson. Retrieved January 12, 2019.

This land they gave name to, and called it Helluland (stone-land).

- CBC, The Nature of Things episode "The Norse: An Arctic Mystery", season 2012–2013 episode 5 airdate 22 November 2012; archived at the Wayback Machine, November 27, 2012.

- George, Jane. "Hare fur yarn, wooden tally sticks may mean visitors arrived 1,000 years ago". Nunatsiaq News. Archived from the original on August 1, 2018.

- Stueck, Wendy; Taylor, Kate (December 4, 2014). "Canadian Museum of History reveals researcher was fired for harassment". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved January 3, 2019.

On the program, host Carol Off interviewed Dr. Sutherland […] Off asked Dr. Sutherland whether she might have been fired from the Canadian Museum of Civilization (which was renamed the Canadian Museum of History last year) because her research was out of step with government views of Canadian history. Sutherland agreed […]

- Barber, Elizabeth Wayland (1992) Prehistoric Textiles: The Development of Cloth in the Neolithic and Bronze Ages with Special Reference to the Aegean, Princeton University Press, "We now have at least two pieces of evidence that this important principle of twisting for strength dates to the Palaeolithic. In 1953, the Abbé Glory was investigating floor deposits in a steep corridor of the famed Lascaux caves in southern France […] a long piece of Palaeolithic cord […] neatly twisted in the S direction […] from three Z-plied strands […]" ISBN 0-691-00224-X

- Smith, Michèle Hayeur; Smith, Kevin P.; Nilsen, Gørill (August 2018). "Journal of Archaeological Science". Dorset, Norse, or Thule? Technological Transfers, Marine Mammal Contamination, and AMS Dating of Spun Yarn and Textiles from the Eastern Canadian Arctic. Elsevier. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2018.06.005. S2CID 52035803.

However, the date received on Sample 4440b from Nanook clearly indicates that sinew was being spun and plied at least as early, if not earlier, than yarn at this site. We feel that the most parsimonious explanation of this data is that the practice of spinning hair and wool into plied yarn most likely developed naturally within this context of complex, indigenous, Arctic fiber technologies, and not through contact with European textile producers.

- Jarus, Owen (October 16, 2018). "Do Canadian Carvings Depict Vikings? Removing Mammal Fat May Tell". Live Science. Retrieved January 14, 2019.

This shows that the indigenous peoples in the Canadian Arctic developed yarn-spinning technologies without any help from the Vikings

- "Tanfield Valley on Baffin Island: Proven Viking Site in North America". www.vikingrune.com.

- Armstrong, Jane (November 20, 2012). "Vikings in Canada?". A researcher says she’s found evidence that Norse sailors may have settled in Canada’s Arctic. Others aren’t so sure. Maclean's. Retrieved January 15, 2019.

In fact, Fitzhugh thinks the cord at the centre of Sutherland’s “eureka” moment is a Dorset artifact. “We have very good evidence that this kind of spun cordage was being used hundreds of years before the Norse arrived in the New World, in other words 500 to 600 CE, at the least,” he says.

- Jarus, Owen (March 6, 2018). "Archaeologists Closer to Finding Lost Viking Settlement". Live Science. Retrieved January 14, 2019.

If Hóp is found it would be the second Viking settlement to be discovered in North America. The other is at L'Anse aux Meadows on the northern tip of Newfoundland.

- "Statistics Canada. 2017. Census Profile. 2016 Census. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98-316-X2016001. Ottawa. Released August 2, 2017". February 8, 2017. Retrieved August 21, 2017.

- "Statistics Canada. 2007. 2006 Community Profiles. 2006 Census. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 92-591-XWE. Ottawa. Released March 13, 2007". March 13, 2007. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- The Mary River Project Archived 2010-05-29 at the Wayback Machine

- Icebergs, feasts and culture in Pond Inlet, Nunavut, CBC News

- "Arctic Wolf". Animalia. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "Facts About Baffin Island". Retrieved October 3, 2016.

- C. Michael Hogan (2008) Polar Bear: Ursus maritimus, globalTwitcher.com, ed. Nicklas Stromberg

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada Archived 2006-02-07 at the Wayback Machine

- Jeff W. Higdon; D. Bruce Stewart (2018). State of Circumpolar Walrus Populations (PDF) (Report). WWF Arctic. p. 18. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- GHCN average monthly temperatures, GISS data for 1971–2000, Goddard Institute for Space Studies

- Pell, J., Grütter H., Neilson S., Lockhart, G., Dempsey, S. and Grenon, H. 2013. Exploration and discovery of the Chidliak Kimberlite Province, Baffin Island, Nunavut: Canada’s newest diamond district. Proceedings of the 10th International Kimberlite Conference, Bangalore; Springer, New Delhi; extended abstract, 4 p.

Maps

- Reykjavík, 64°08′N 21°56′W

Further reading

- Boas, Franz, and Ludger Müller-Wille. Franz Boas Among the Inuit of Baffin Island, 1883–1884 Journals and Letters. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1998. ISBN 0-8020-4150-7

- Kuhnlein HV, R Soueida, and O Receveur. 1996. "Dietary Nutrient Profiles of Canadian Baffin Island Inuit Differ by Food Source, Season, and Age". Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 96, no. 2: 155–62.

- Lee, Alastair. Baffin Island: the Ascent of Mount Asgard. London: Frances Lincoln, 2011. ISBN 9780711232211

- Matthiasson, John S. Living on the Land Change Among the Inuit of Baffin Island. Peterborough, Canada: Broadview Press, 1992. ISBN 0-585-30561-7

- Maxwell, Moreau S. Archaeology of the Lake Harbour District, Baffin Island. Mercury series. Ottawa: Archaeological Survey of Canada, National Museum of Man, National Museums of Canada, 1973.

- Sabo, George. Long Term Adaptations Among Arctic Hunter-Gatherers A Case Study from Southern Baffin Island. The Evolution of North American Indians. New York: Garland Pub, 1991. ISBN 0-8240-6111-X

- Sergy, Gary A. The Baffin Island Oil Spill Project. Edmonton, Alta: Environment Canada, 1986.

- Stirling, Ian, Wendy Calvert, and Dennis Andriashek. Population Ecology Studies of the Polar Bear in the Area of Southeastern Baffin Island. [Ottawa]: Canadian Wildlife Service, 1980. ISBN 0-662-11097-8

- Utting, D. J. Report on ice-flow history, deglacial chronology, and surficial geology, Foxe Peninsula, southwest Baffin Island, Nunavut. [Ottawa]: Geological Survey of Canada, 2007. http://dsp-psd.pwgsc.gc.ca/collection%5F2007/nrcan-rncan/M44-2007-C2E.pdf. ISBN 978-0-662-46367-2

External links

- Logbooks of the ship "Rosie" (1924-1925) at Dartmouth College Library

- Logbooks of the schooner "Vera" (1920) at Dartmouth College Library

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Baffin Island. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Baffin Island. |