Lixus (ancient city)

Lixus is the site of an ancient Roman-Berber-Punic city located in Morocco, just north of the modern seaport of Larache on the bank of the Loukkos River. The location was one of the main cities of the Roman province of Mauretania Tingitana.[1]

The ruins of Lixus | |

Shown within Morocco | |

| Location | Larache, Larache Province, Tanger-Tetouan-Al Hoceima, Morocco |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 35°12′00″N 06°06′40″W |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Founded | 7th century BC |

Geography

Ancient Lixus is located on Tchemmich Hill on the right bank of the Loukkos River (other names: Oued Loukous; Locus River). It lies just to the north of the modern seaport of Larache.[2] The site lies within the urban perimeter of Larache, and about three kilometres inland from the mouth of the river and the Atlantic ocean. From its 80 metres above the plain the site dominates the marshes through which the river flows. To the north, Lixus is surrounded by hills which themselves are bordered to the north and east by a forest of cork oaks.

Among the ruins are Roman baths, temples, 4th-century walls, a mosaic floor, a Christian church and the intricate and confusing remains of the Capitol Hill.[3]

History

Legends

Some ancient Greek writers located at Lixus the mythological garden of the Hesperides, the keepers of the golden apples. The name of the city was often mentioned by writers from Hanno the Navigator to the Geographer of Ravenna, and confirmed by the legend on its coins and by an inscription. The ancients believed Lixus to be the site of the Garden of the Hesperides and of a sanctuary of Hercules, where Hercules gathered gold apples, more ancient than the one at Cadiz, Spain. However, there are no grounds for the claim that Lixus was founded at the end of the second millennium BC.

Phoenicians

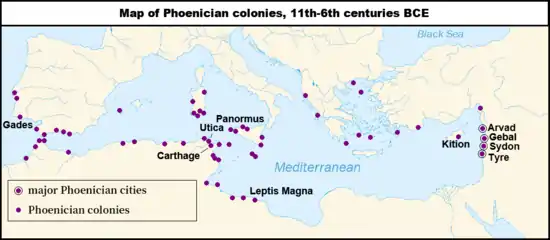

Lixus (Punic: 𐤋𐤊𐤔, LKŠ)[4][5] was first settled by the Phoenicians in the 8th or 7th century BC and was later controlled directly from Carthage. It was part of a chain of Punic towns along the Atlantic coast of modern Morocco; other major settlements further to the south are Chellah (called Sala Colonia by the Romans)[6] and Mogador. When Carthage's empire fell to Rome during the Punic Wars, Lixus, Chellah, and Mogador became outposts of the province of Mauretania Tingitana.

Ambiguous "Punicity"

Archaeologist, Pierre Cintas, in 1954 concluded that while Carthaginian pottery was discovered in Moroccan sites, no archaeological evidence existed for the presence of Carthaginian settlers in Lixus even though historians identified the city as being one of Phoenician foundation and serving as an important city of the Punic west.[7]

Armand Luquet, in the 1970s also found insufficient archaeological data which could serve as evidence for Carthaginian settlement of Lixus.[8]

In relation to the 'Punicity' of Moroccan sites such as Lixus, Professor Josephine Crawley Quinn stresses an ambiguity: "It is not in fact easy to demonstrate any occupation of coastal sites by Carthaginian colonists or other settlers, since most of the sites traditionally labelled 'Punic' could be interpreted equally well as indigenous settlements engaged in the exchange of local products for imported goods."[9]

Roman Empire

Lixus flourished during the Roman Empire, mainly when the emperor Claudius (AD 41-54) established the province of Africa with full rights for the citizens. Lixus was one of the few Roman cities in Berber Africa that enjoyed an amphitheater. In the third century, Lixus became nearly fully Christian and there are even now the ruins of a Paleochristian church overlooking the archaeological area.[10]

Archaeological work

The site was excavated continuously from 1948 to 1969.[11] In the 1960s, Lixus was restored and consolidated. In 1989, following an international conference which brought together many scientists, specialists, historians and archaeologists of the Mediterranean around the history and archaeology of Lixus, the site was partly enclosed. Work was undertaken to study the Roman mosaics of the site, which constitute a very rich unit. Lixus was on a surface of approximately 75 hectares (190 acres). The excavated zones constitute approximately 20% of the total surface of the site.

World Heritage Status

This site was added to the UNESCO World Heritage Tentative List on July 1, 1995 in the Cultural category.

See also

References

Citations

- Rachid Mueden (2010). "Las colonias y municipios de la Mauritania Tingitana" (PDF). Adrastea.urg.es. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- Prehistoria de España: Trabajos dedicados al IV Congreso Internacional, Santiago Alcobé y Noguer

- "Sites Antiques". Miniculture.gov.ma (in French). Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- Mora Serrano (2011), p. 22.

- Ghaki (2015), p. 67.

- C. Michael Hogan, Chellah, The Megalithic Portal, ed. Andy Burnham

- Cintas, Pierre (1954). Contribution à l'étude de l'expansion carthaginoise au Maroc. Paris, Arts et métiers graphiques.

- Armand, Luquet (1973–1975). 'Contribution à l’Atlas Archéologique du Maroc. Le Maroc Punique'. 9. Bulletin d'Archéologie Marocaine. p. 237–93.

- Quinn, Josephine Crawley (2014). The Punic Mediterranean: Identities And Identification From Phoenician Settlement To Roman Rule (British School At Rome Studies). Cambridge University Press. p. 203.

- "Lonely Roman ruins". Lexicorient.com. Archived from the original on 16 July 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- The Phoenicians, by Sabatino Moscati

Bibliography

- Ghaki, Mansour (2015), "Toponymie et Onomastique Libyques: L'Apport de l'Écriture Punique/Néopunique" (PDF), La Lingua nella Vita e la Vita della Lingua: Itinerari e Percorsi degli Studi Berberi, Studi Africanistici: Quaderni di Studi Berberi e Libico-Berberi (in French), No. 4, Naples: Unior, pp. 65–71, ISBN 978-88-6719-125-3, ISSN 2283-5636

- Mora Serrano, Bartolomé (2011), "Coins, Cities, and Territories: The Imaginary Far West and South Iberian and North African Punic Coins", Money, Trade, and Trade Routes in Pre-Islamic North Africa, London: British Museum, pp. 21–32.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lixus (ancient city). |

%252C_Algeria_04966r.jpg.webp)