Tipasa

Tipasa, sometimes distinguished as Tipasa in Mauretania, was a colonia in the Roman province Mauretania Caesariensis, nowadays called Tipaza, and located in coastal central Algeria. Since 2002, it has been declared by UNESCO a World Heritage Site.

Tipasa

Tipaza | |

|---|---|

| |

Tipasa Location in Algeria | |

| Coordinates: 36°35′31″N 2°26′58″E | |

| Official name | Tipasa |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | iii, iv |

| Designated | 1982 (6th session) |

| Reference no. | 193 |

| State Party | |

| Region | Arab States |

| Endangered | 2002–2006 |

History

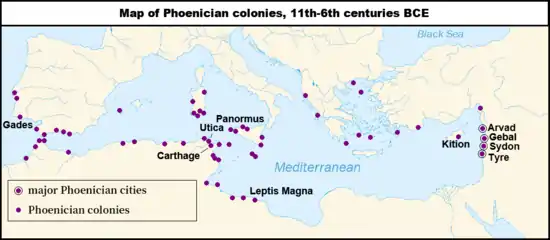

Punic trading post

Initially the city was a small ancient Punic trading-post.

Roman colony

Conquered by Ancient Rome, it was turned into a military colony by the emperor Claudius for the conquest of the kingdoms of Mauretania.[1] Afterwards it became a municipium called Colonia Aelia Augusta Tipasensium, that reached the population of 20,000 inhabitants in the fourth century according to historian Gsell.[2]

The Roman city was built on three small hills which overlooked the sea, nearly 20 km. east from Caesarea (capital of Mauretania Caesariensis). Of the houses, most of which stood on the central hill, no traces remain; but there are ruins of three churches — the Great Basilica and the Basilica Alexander on the western hill, and the Basilica of St Salsa on the eastern hill, two cemeteries, the baths, theatre, amphitheatre and nymphaeum. The line of the ramparts can be distinctly traced and at the foot of the eastern hill the remains of the ancient harbour.

The basilicas are surrounded by cemeteries, which are full of coffins, all of stone and covered with mosaics. The basilica of St. Salsa, which has been excavated by Stéphane Gsell, consists of a nave and two aisles, and still contains a mosaic. The Great Basilica served for centuries as a quarry, but it is still possible to make out the plan of the building, which was divided into seven aisles. Under the foundations of the church are tombs hewn out of the solid rock. Of these one is circular, with a diameter of 18 m and space for 24 coffins.

Under Roman rule the city acquired greater commercial and military importance because of its harbour and its central position on the system of Roman coastal roads in North Africa. A wall of approximately 7,500 feet (2,300 metres) was built around the city for defense against nomadic tribes, and Roman public buildings and districts of houses were constructed within the enclosure. Tipasa became an important centre of Christianity in the 3rd century. The first Christian inscription in Tipasa dates to 238, and the city saw the construction of numerous Christian religious buildings in the later 3rd and 4th centuries.....About 372 Tipasa withstood an assault by Firmus, the leader of a Berber rebellion that had overrun the nearby cities of Caesarea (modern Cherchell) and Icosium (modern Algiers). Tipasa then served as the base for the Roman counter-campaign.However, Tipasa’s fortifications did not prevent the city from being conquered by the Vandals about 429, bringing to an end the prosperity that the city had enjoyed during the Roman period. In 484, during the persecution of the Catholic church by the Vandal king Huneric, the Catholic bishop of Tipasa was expelled and replaced with an Arian bishop—prompting many inhabitants of the city to flee to Spain. In the ensuing decades the city fell into ruin. Encyclopædia Britannica[3]

Commercially Tipasa was of considerable importance, but it was not distinguished in art or learning. Christianity was early introduced, and in the third century Tipasa was an episcopal see, now inscribed in the Catholic Church's list of titular sees.[4]

Most of the inhabitants continued to be non-Christian until, according to the legend, Salsa, a Christian maiden, threw the head of their serpent idol into the sea, whereupon the enraged populace stoned her to death. The body, miraculously recovered from the sea, was buried, on the hill above the harbour, in a small chapel which gave place subsequently to the stately basilica. Salsa's martyrdom took place in the 4th century. In 484 the Vandal king Huneric (477‑484) sent an Arian bishop to Tipaza; whereupon many of the inhabitants fled to Spain, while many of the remainder were cruelly persecuted.[5]

Decline

Tipasa was partially destroyed by the Vandals in 430, but was rebuilt by the Byzantines one century later. Tipasa revived for a brief time during the Byzantine occupation in the 6th century but was given the Arabic language name, Tefassed, when Arabs arrived there. The term translated means badly damaged.[6]

In the third century Christianity was worshipped by all the Romanised Berbers and Roman colonists of Tipasa. From this period comes the oldest Christian epitaph in Roman Africa dated October 17, 237 AD.[7] In Tipasa were built the biggest basilicas of actual Algeria: the Alexander basilica and the basilica of Saint Salsa.

At the end of the seventh century the city was destroyed by the Arabs and reduced to ruins.[8]

Gallery

View of Tipasa, Algeria

View of Tipasa, Algeria Roman ruins of Tipasa (basilica)

Roman ruins of Tipasa (basilica) Vestiges of the Christian church

Vestiges of the Christian church Roman ruins of Tipasa

Roman ruins of Tipasa View of Tipasa, Algeria

View of Tipasa, Algeria Panoramic view of Tipasa

Panoramic view of Tipasa

view showing base of walls

view showing base of walls

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ancient Roman archaeological sites in Tipaza. |

References

Citations

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Tipasa". whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 2016-08-08.

- "Archivo de la Frontera | EL LIMES ROMANO DE ÁFRICA IX – AELIA AUGUSTA TIPASENSIUM (Tipasa – Argelia, 1982-84)". www.archivodelafrontera.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 2018-01-29.

- Roman Tipasa

- Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2013, ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 991

- Stefano Antonio Morcelli, Africa christiana, Volume I, Brescia 1816, pp. 327–328

- Tipasa, Morocco, Algeria, & Tunisia: a travel survival kit, Geoff Crowther & Hugh Finlay, Lonely Planet, 2nd Edition, April 1992, pp. 286 - 287.

- Revue africaine, Société historique algérienne, éd. la Société, 1866, p. 487

- Toutain Jules. Fouilles de M. Gsell à Tipasa : Basilique de Sainte Salsa. In: Mélanges d'archéologie et d'histoire T. 11, 1891. p. 179-185.

Bibliography

- Head, Barclay; et al. (1911), "Numidia", Historia Numorum (2nd ed.), Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp. 884–887.

%252C_Algeria_04966r.jpg.webp)

.svg.png.webp)