Longevity

The word "longevity" is sometimes used as a synonym for "life expectancy" in demography. However, the term longevity is sometimes meant to refer only to especially long-lived members of a population, whereas life expectancy is always defined statistically as the average number of years remaining at a given age. For example, a population's life expectancy at birth is the same as the average age at death for all people born in the same year (in the case of cohorts). Longevity is best thought of as a term for general audiences meaning 'typical length of life' and specific statistical definitions should be clarified when necessary.

Reflections on longevity have usually gone beyond acknowledging the brevity of human life and have included thinking about methods to extend life. Longevity has been a topic not only for the scientific community but also for writers of travel, science fiction, and utopian novels.

There are many difficulties in authenticating the longest human life span ever by modern verification standards, owing to inaccurate or incomplete birth statistics. Fiction, legend, and folklore have proposed or claimed life spans in the past or future vastly longer than those verified by modern standards, and longevity narratives and unverified longevity claims frequently speak of their existence in the present.

A life annuity is a form of longevity insurance.

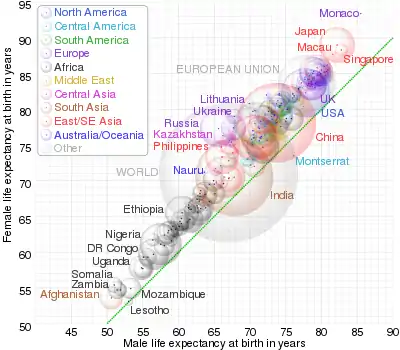

Life expectancy, as of 2010

Various factors contribute to an individual's longevity. Significant factors in life expectancy include gender, genetics, access to health care, hygiene, diet and nutrition, exercise, lifestyle, and crime rates. Below is a list of life expectancies in different types of countries:[3]

- Developed countries: 77–90 years (e.g. Canada: 81.29 years, 2010 est.)

- Developing countries: 32–80 years (e.g. Mozambique: 41.37 years, 2010 est.)

Population longevities are increasing as life expectancies around the world grow:[1][4]

- Australia: 80 years in 2002, 81.72 years in 2010

- France: 79.05 years in 2002, 81.09 years in 2010

- Germany: 77.78 years in 2002, 79.41 years in 2010

- Italy: 79.25 years in 2002, 80.33 years in 2010

- Japan: 81.56 years in 2002, 82.84 years in 2010

- Monaco: 79.12 years in 2002, 79.73 years in 2011

- Spain: 79.06 years in 2002, 81.07 years in 2010

- UK: 80 years in 2002, 81.73 years in 2010

- USA: 77.4 years in 2002, 78.24 years in 2010

Long-lived individuals

The Gerontology Research Group validates current longevity records by modern standards, and maintains a list of supercentenarians; many other unvalidated longevity claims exist. Record-holding individuals include:[5][6][7]

- Eilif Philipsen (1682–1785, 102 years, 333 days): first person to reach the ages of 100, 101, and 102 (on July 21, 1782) and whose age could be validated.

- Geert Adriaans Boomgaard (1788–1899, 110 years, 135 days): first person to reach the age of 110 (on September 21, 1898) and whose age could be validated.

- Margaret Ann Neve, (18 May 1792 – 4 April 1903, 110 years, 346 days) the first validated female supercentenarian (on 18 May 1902).

- Jeanne Calment (1875–1997, 122 years, 164 days): the oldest person in history whose age has been verified by modern documentation.[note 1] This defines the modern human life span, which is set by the oldest documented individual who ever lived.

- Sarah Knauss (1880–1999, 119 years, 97 days): the second oldest documented person in modern times and the oldest American.

- Jiroemon Kimura (1897–2013, 116 years, 54 days): the oldest man in history whose age has been verified by modern documentation.

Major factors

Evidence-based studies indicate that longevity is based on two major factors, genetics and lifestyle choices.[9]

Genetics

Twin studies have estimated that approximately 20-30% of the variation in human lifespan can be related to genetics, with the rest due to individual behaviors and environmental factors which can be modified.[10] Although over 200 gene variants have been associated with longevity according to a US-Belgian-UK research database of human genetic variants,[11] these explain only a small fraction of the heritability.[12] A 2012 study found that even modest amounts of leisure time and physical exercise can extend life expectancy by as much as 4.5 years.[13]

Lymphoblastoid cell lines established from blood samples of centenarians have significantly higher activity of the DNA repair protein PARP (Poly ADP ribose polymerase) than cell lines from younger (20 to 70 year old) individuals.[14] The lymphocytic cells of centenarians have characteristics typical of cells from young people, both in their capability of priming the mechanism of repair after H2O2 sublethal oxidative DNA damage and in their PARP gene expression.[15] These findings suggest that elevated PARP gene expression contributes to the longevity of centenarians, consistent with the DNA damage theory of aging.[16]

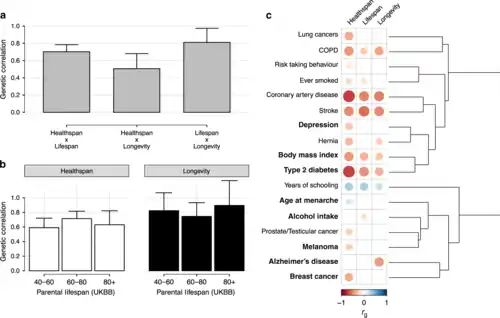

In July 2020 scientists, using public biological data on 1.75 m people with known lifespans overall, identify 10 genomic loci which appear to intrinsically influence healthspan, lifespan, and longevity – of which half have not been reported previously at genome-wide significance and most being associated with cardiovascular disease – and identify haem metabolism as a promising candidate for further research within the field. Their study suggests that high levels of iron in the blood likely reduce, and genes involved in metabolising iron likely increase healthy years of life in humans.[18][17]

Change over time

In preindustrial times, deaths at young and middle age were more common than they are today. This is not due to genetics, but because of environmental factors such as disease, accidents, and malnutrition, especially since the former were not generally treatable with pre-20th-century medicine. Deaths from childbirth were common for women, and many children did not live past infancy. In addition, most people who did attain old age were likely to die quickly from the above-mentioned untreatable health problems. Despite this, there are many examples of pre-20th-century individuals attaining lifespans of 85 years or greater, including John Adams, Cato the Elder, Thomas Hobbes, Eric of Pomerania, Christopher Polhem, and Michelangelo. This was also true for poorer people like peasants or laborers. Genealogists will almost certainly find ancestors living to their 70s, 80s and even 90s several hundred years ago.

For example, an 1871 census in the UK (the first of its kind, but personal data from other censuses dates back to 1841 and numerical data back to 1801) found the average male life expectancy as being 44, but if infant mortality is subtracted, males who lived to adulthood averaged 75 years. The present life expectancy in the UK is 77 years for males and 81 for females, while the United States averages 74 for males and 80 for females.

Studies have shown that black American males have the shortest lifespans of any group of people in the US, averaging only 69 years (Asian-American females average the longest).[23] This reflects overall poorer health and greater prevalence of heart disease, obesity, diabetes, and cancer among black American men.

Women normally outlive men. Theories for this include smaller bodies (and thus less stress on the heart), a stronger immune system (since testosterone acts as an immunosuppressant), and less tendency to engage in physically dangerous activities.

There is debate as to whether the pursuit of longevity is a worthwhile health care goal. Bioethicist Ezekiel Emanuel, who is also one of the architects of ObamaCare, has argued that the pursuit of longevity via the compression of morbidity explanation is a "fantasy" and that longevity past age 75 should not be considered an end in itself.[24] This has been challenged by neurosurgeon Miguel Faria, who states that life can be worthwhile in healthy old age, that the compression of morbidity is a real phenomenon, and that longevity should be pursued in association with quality of life.[25] Faria has discussed how longevity in association with leading healthy lifestyles can lead to the postponement of senescence as well as happiness and wisdom in old age.[26]

Limited longevity

All of the biological organisms have a limited longevity, and different species of animals and plants have different potentials of longevity. Misrepair-accumulation aging theory[27][28] suggests that the potential of longevity of an organism is related to its structural complexity.[29] Limited longevity is due to the limited structural complexity of the organism. If a species of organisms has too high structural complexity, most of its individuals would die before the reproduction age, and the species could not survive. This theory suggests that limited structural complexity and limited longevity are essential for the survival of a species.

Longevity myths

Longevity myths are traditions about long-lived people (generally supercentenarians), either as individuals or groups of people, and practices that have been believed to confer longevity, but for which scientific evidence does not support the ages claimed or the reasons for the claims.[30][31] A comparison and contrast of "longevity in antiquity" (such as the Sumerian King List, the genealogies of Genesis, and the Persian Shahnameh) with "longevity in historical times" (common-era cases through twentieth-century news reports) is elaborated in detail in Lucian Boia's 2004 book Forever Young: A Cultural History of Longevity from Antiquity to the Present and other sources.[32]

After the death of Juan Ponce de León, Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés wrote in Historia General y Natural de las Indias (1535) that Ponce de León was looking for the waters of Bimini to cure his aging.[33] Traditions that have been believed to confer greater human longevity also include alchemy,[34] such as that attributed to Nicolas Flamel. In the modern era, the Okinawa diet has some reputation of linkage to exceptionally high ages.[35]

Longevity claims may be subcategorized into four groups: "In late life, very old people often tend to advance their ages at the rate of about 17 years per decade .... Several celebrated super-centenarians (over 110 years) are believed to have been double lives (father and son, relations with the same names or successive bearers of a title) .... A number of instances have been commercially sponsored, while a fourth category of recent claims are those made for political ends ...."[36] The estimate of 17 years per decade was corroborated by the 1901 and 1911 British censuses.[36] Time magazine considered that, by the Soviet Union, longevity had been elevated to a state-supported "Methuselah cult".[37] Robert Ripley regularly reported supercentenarian claims in Ripley's Believe It or Not!, usually citing his own reputation as a fact-checker to claim reliability.[38]

Future

The United Nations has also made projections far out into the future, up to 2300, at which point it projects that life expectancies in most developed countries will be between 100 and 106 years and still rising, though more and more slowly than before. These projections also suggest that life expectancies in poor countries will still be less than those in rich countries in 2300, in some cases by as much as 20 years. The UN itself mentioned that gaps in life expectancy so far in the future may well not exist, especially since the exchange of technology between rich and poor countries and the industrialization and development of poor countries may cause their life expectancies to converge fully with those of rich countries long before that point, similarly to the way life expectancies between rich and poor countries have already been converging over the last 60 years as better medicine, technology, and living conditions became accessible to many people in poor countries. The UN has warned that these projections are uncertain, and cautions that any change or advancement in medical technology could invalidate such projections.[39]

Recent increases in the rates of lifestyle diseases, such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease, may eventually slow or reverse this trend toward increasing life expectancy in the developed world, but have not yet done so. The average age of the US population is getting higher[40] and these diseases show up in older people.[41]

Jennifer Couzin-Frankel examined how much mortality from various causes would have to drop in order to boost life expectancy and concluded that most of the past increases in life expectancy occurred because of improved survival rates for young people. She states that it seems unlikely that life expectancy at birth will ever exceed 85 years.[42] Michio Kaku argues that genetic engineering, nanotechnology and future breakthroughs will accelerate the rate of life expectancy increase indefinitely.[43] Already genetic engineering has allowed the life expectancy of certain primates to be doubled, and for human skin cells in labs to divide and live indefinitely without becoming cancerous.[44]

Reliable data from 1840 through 2002 indicates life expectancy has risen linearly for men and women, albeit more slowly for men. For women the increase has been almost three months per year, for men almost 2.7 months per year. In light of steady increase, without any sign of limitation, the suggestion that life expectancy will top out must be treated with caution. Scientists Oeppen and Vaupel observe that experts who assert that "life expectancy is approaching a ceiling ... have repeatedly been proven wrong." It is thought that life expectancy for women has increased more dramatically owing to the considerable advances in medicine related to childbirth.[45]

Non-human biological longevity

Currently living:

- A 5,070-year-old member of the species Pinus longaeva: Oldest known currently living non-clonal tree.[46]

- Methuselah: 4,800-year-old bristlecone pine in the White Mountains of California, the second oldest currently living non-clonal tree.[46]

Dead:

- The quahog clam (Arctica islandica) is exceptionally long-lived, with a maximum recorded age of 507 years, the longest of any animal.[47] Other clams of the species have been recorded as living up to 374 years.[48]

- Lamellibrachia luymesi, a deep-sea cold-seep tubeworm, is estimated to reach ages of over 250 years based on a model of its growth rates.[49]

- A bowhead whale killed in a hunt was found to be approximately 211 years old (possibly up to 245 years old), the longest-lived mammal known.[50]

Revived:

See also

- Actuarial science

- Aging

- Aging brain

- Alliance for Aging Research

- Anti-aging movement

- Biodemography

- Biodemography of human longevity

- Calico (company)

- Centenarian

- DNA damage theory of aging

- Genetics of aging

- Gerontology Research Group

- Hayflick limit

- Indefinite lifespan

- Life extension

- List of aging processes

- List of last survivors of historical events

- Longevity claims

- Longevity myths

- Maximum life span

- Mitohormesis

- Oldest viable seed

- Reliability theory of aging and longevity

- Research into centenarians

- Senescence

Notes

References

Citations

- "Life expectancy at birth, Country Comparison to the World". CIA World Factbook. US Central Intelligence Agency. n.d. Retrieved 12 Jan 2011.

- "Field Listing: Population, Country Comparison to the World". CIA World Factbook. US Central Intelligence Agency. n.d. Retrieved 12 Jan 2011.

- The US Central Intelligence Agency, 2010, CIA World Factbook, retrieved 12 Jan. 2011, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/index.html

- The US Central Intelligence Agency, 2002, CIA World Factbook, retrieved 12 Jan. 2011, http://www.theodora.com/wfb/2002/index.html

- Nuwer, Rachel. "Keeping Track of the Oldest People in the World". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2019-01-13.

- Gavrilova, Natalia S.; Gavrilov, Leonid A.; Krut'ko, Vyacheslav N. (2017). "Mortality Trajectories at Exceptionally High Ages: A Study of Supercentenarians". Living to 100 Monograph. 2017 (1B). PMC 5696798. PMID 29170764.

- Thatcher, A. Roger (2010), "The growth of high ages in England and Wales, 1635-2106", Supercentenarians, Demographic Research Monographs, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 191–201, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-11520-2_11, ISBN 9783642115196

- Milova, Elena (4 November 2018). "Valery Novoselov: Investigating Jeanne Calment's Longevity Record". Life Extension Advocacy Foundation. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- Marziali, Carl (7 December 2010). "Reaching Toward the Fountain of Youth". USC Trojan Family Magazine. Archived from the original on 13 December 2010. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- Hjelmborg, J.; Iachine, Ivan; Skytthe, Axel; Vaupel, James W.; McGue, Matt; Koskenvuo, Markku; Kaprio, Jaakko; Pedersen, Nancy L.; Christensen, Kaare; et al. (2006). "Genetic influence on human lifespan and longevity". Human Genetics. 119 (3): 312–321. doi:10.1007/s00439-006-0144-y. PMID 16463022. S2CID 8470835.

- "LongevityMap". Human Ageing Genomic Resources. senescence.info by João Pedro de Magalhães. n.d. Retrieved 2013-09-23.

- Budovsky, A.; Craig, Thomas; Wang, Jingwei; Tacutu, Robi; Csordas, Attila; Lourenço, Joana; Fraifeld, Vadim E.; De Magalhães, João Pedro; et al. (2013). "LongevityMap: A database of human genetic variants associated with longevity". Trends in Genetics. 29 (10): 559–560. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2013.08.003. PMID 23998809.

- Moore, S.C.; et al. (2012). "Leisure time physical activity of moderate to vigorous intensity and mortality: A large pooled cohort analysis". PLOS Medicine. 9 (11): e1001335. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001335. PMC 3491006. PMID 23139642.

- Muiras ML, Müller M, Schächter F, Bürkle A (1998). "Increased poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activity in lymphoblastoid cell lines from centenarians". J. Mol. Med. 76 (5): 346–54. doi:10.1007/s001090050226. PMID 9587069. S2CID 24616650.

- Chevanne M, Calia C, Zampieri M, Cecchinelli B, Caldini R, Monti D, Bucci L, Franceschi C, Caiafa P (2007). "Oxidative DNA damage repair and parp 1 and parp 2 expression in Epstein-Barr virus-immortalized B lymphocyte cells from young subjects, old subjects, and centenarians". Rejuvenation Res. 10 (2): 191–204. doi:10.1089/rej.2006.0514. PMID 17518695.

- Bernstein H, Payne CM, Bernstein C, Garewal H, Dvorak K (2008). Cancer and aging as consequences of un-repaired DNA damage. In: New Research on DNA Damages (Editors: Honoka Kimura and Aoi Suzuki) Nova Science Publishers, Inc., New York, Chapter 1, pp. 1-47. open access, but read only https://www.novapublishers.com/catalog/product_info.php?products_id=43247 ISBN 1604565810 ISBN 978-1604565812

- Timmers, Paul R. H. J.; Wilson, James F.; Joshi, Peter K.; Deelen, Joris (16 July 2020). "Multivariate genomic scan implicates novel loci and haem metabolism in human ageing". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 3570. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-17312-3. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7366647. PMID 32678081.

Text and images are available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Text and images are available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. - "Blood iron levels could be key to slowing ageing, gene study shows". phys.org. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- Tiantian Liu, Nicole M Gatto, Zhong Chen, Hongyu Qiu, Grace Lee, Penelope Duerksen-Hughes, Gary Fraser, Charles Wang, Vegetarian diets, circulating miRNA expression and healthspan in subjects living in the Blue Zone, Precision Clinical Medicine, , pbaa037

- Sebastian Brandhorst, Valter D Longo, Protein Quantity and Source, Fasting-Mimicking Diets, and Longevity, Advances in Nutrition, Volume 10, Issue Supplement_4, November 2019, Pages S340–S350.

- "Promoting Health and Longevity through Diet: From Model Organisms to Humans". Cell. 161 (1): 106–118. 2015-03-26. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.020. ISSN 0092-8674.

- Longo, Valter D.; Antebi, Adam; Bartke, Andrzej; Barzilai, Nir; Brown‐Borg, Holly M.; Caruso, Calogero; Curiel, Tyler J.; Cabo, Rafael de; Franceschi, Claudio; Gems, David; Ingram, Donald K. (2015). "Interventions to Slow Aging in Humans: Are We Ready?". Aging Cell. 14 (4): 497–510. doi:10.1111/acel.12338. ISSN 1474-9726. PMC 4531065. PMID 25902704.

- Keaten, John (17 October 2012). "Health in America Today" (PDF). Measure of America. Retrieved 17 October 2012.

- Emanuel EJ. "Why I hope to die at 75: An argument that society and families - and you - will be better off if nature takes its course swiftly and promptly". The Atlantic. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- Faria MA. "Bioethics and why I hope to live beyond age 75 attaining wisdom!: A rebuttal to Dr. Ezekiel Emanuel′s 75 age limit". Surg Neurol Int 2015;6:35. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- Faria MA. "Longevity and compression of morbidity from a neuroscience perspective: Do we have a duty to die by a certain age?". Surg Neurol Int 2015;6:49. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- Wang, Jicun; Michelitsch, Thomas; Wunderlin, Arne; Mahadeva, Ravi (2009). "Aging as a consequence of Misrepair –a novel theory of aging". arXiv:0904.0575 [q-bio.TO].

- Wang-Michelitsch, Jicun; Michelitsch, Thomas (2015). "Aging as a process of accumulation of Misrepairs". arXiv:1503.07163 [q-bio.TO].

- Wang-Michelitsch, Jicun; Michelitsch, Thomas (2015). "Potential of longevity: hidden in structural complexity". arXiv:1505.03902 [q-bio.TO].

- Ni, Maoshing (2006). Secrets of Longevity. Chronicle Books. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-8118-4949-4.

Chuan xiong ... has long been a key herb in the longevity tradition of China, prized for its powers to boost the immune system, activate blood circulation, and relieve pain.

- Fulder, Stephen (1983). An End to Ageing: Remedies for Life. Destiny Books. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-89281-044-4.

Taoist devotion to immortality is important to us for two reasons. The techniques may be of considerable value to our goal of a healthy old age, if we can understand and adapt them. Secondly, the Taoist longevity tradition has brought us many interesting remedies.

- Vallin, Jacques; Meslé, France (February 2001). "Living Beyond the Age of 100" (PDF). Bulletin Mensuel d'Information de l'Institut National d'Études Démographiques: Population & Sociétés. Institut National d'Études Démographiques (365). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 September 2012.

- Fernández de Oviedo, Gonzalo. Historia General y Natural de las Indias, book 16, chapter XI.

- Kohn, Livia (2001). Daoism and Chinese Culture. Three Pines Press. pp. 4, 84. ISBN 978-1-931483-00-1.

- Willcox BJ, Willcox CD, Suzuki M. The Okinawa program: Learn the secrets to healthy longevity. p. 3.

- Guinness Book of World Records. 1983. pp. 16–19.

- "No Methuselahs". Time Magazine. 1974-08-12. Retrieved 2009-05-13.

- Ripley Enterprises, Inc. (September 1969). Ripley's Believe It or Not! 15th Series. New York City: Pocket Books. pp. 112, 84, 56.

The Old Man of the Sea / Yaupa / a native of Futuna, one of the New Hebrides Islands / regularly worked his own farm at the age of 130 / He died in 1899 of measles — a children's disease ... Horoz Ali, the last Turkish gatekeeper of Nicosia, Cyprus, lived to the age of 120 ... Francisco Huppazoli (1587–1702) of Casale, Italy, lived 114 years without a day's illness and had 4 children by his 5th wife — whom he married at the age of 98

- World Population to 2300, United Nations

- https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/2010_census/cb11-cn192.html

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-07-29. Retrieved 2014-07-29.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Jennifer Couzin-Frankel (29 July 2011). "A Pitched Battle Over Life Span". Science. 333 (6042): 549–50. Bibcode:2011Sci...333..549C. doi:10.1126/science.333.6042.549. PMID 21798928.

- Physics of the Future, Michio Kaku

- Michio Kaku interview

- Oeppen, Jim; James W. Vaupel (2002-05-10). "Broken Limits to Life Expectancy". Science. Washington, D.C.: American Association for the Advancement of Science. 296 (5570): 1029–1031. doi:10.1126/science.1069675. PMID 12004104. S2CID 1132260.

- "Rocky Mountain Tree-Ring Research, OLDLIST". Retrieved January 6, 2013.

- Munro D.; Blier P.U. (2012). "The extreme longevity of Arctica islandica is associated with increased peroxidation resistance in mitochondrial membranes". Aging Cell. 11 (5): 845–55. doi:10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00847.x. PMID 22708840. S2CID 205634828.

- Bangor University: 400 year old Clam Found(retrieved 29 October 2007) BBC News: Ming the clam is 'oldest animal' (retrieved 29 October 2007)

- Bergquist DC, Williams FM, Fisher CR (2000). "Longevity record for deep-sea invertebrate". Nature. 403 (6769): 499–500. Bibcode:2000Natur.403..499B. doi:10.1038/35000647. PMID 10676948. S2CID 4357091.

- Rozell (2001) "Bowhead Whales May Be the World's Oldest Mammals" Archived 2009-12-09 at the Wayback Machine, Alaska Science Forum, Article 1529 (retrieved 29 October 2007)

- 250-Million-Year-Old Bacillus permians Halobacteria Revived. October 22, 2000. Bioinformatics Organization. J.W. Bizzaro.

- "The Permian Bacterium that Isn't". Oxford Journals. 2001-02-15. Retrieved 2010-11-16.

Sources

- Lucian Boia (2005) Forever Young: A Cultural History of Longevity from Antiquity to the Present Door Reaktion Books. ISBN 1-86189-154-7.

- James R. Carey & Debra S. Judge (2000) Longevity records: Life Spans of Mammals, Birds, Amphibians, reptiles, and Fish. Odense Monographs on Population Aging 8, ISBN 87-7838-539-3.

- James R. Carey (2003) Longevity. The biology and Demography of Life Span. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-08848-9

- Gavrilova N.S., Gavrilov L.A. (2010) Search for Mechanisms of Exceptional Human Longevity. Rejuvenation Research, 13(2-3): 262–264.

- Gavrilova N.S., Gavrilov L.A. (2008), Can exceptional longevity be predicted? Contingencies [Journal of the American Academy of Actuaries], July/August issue, pp. 82–88.

- Gavrilova N.S., Gavrilov L.A. (2007) Search for Predictors of Exceptional Human Longevity: Using Computerized Genealogies and Internet Resources for Human Longevity Studies. North American Actuarial Journal, 11(1): 49-67

- Gavrilov LA, Gavrilova NS. (2006) Reliability Theory of Aging and Longevity. In: Masoro E.J. & Austad S.N.. (eds.): Handbook of the Biology of Aging, Sixth Edition. Academic Press. San Diego, CA, pp. 3-42.

- Gavrilova, N.S., Gavrilov, L.A. (2005) Human longevity and reproduction: An evolutionary perspective. In: Voland, E., Chasiotis, A. & Schiefenhoevel, W. (eds.): Grandmotherhood - The Evolutionary Significance of the Second Half of Female Life. Rutgers University Press. New Brunswick, NJ, pp. 59-80.

- Leonid A. Gavrilov, Natalia S. Gavrilova (1991), The Biology of Life Span: A Quantitative Approach. New York: Harwood Academic Publisher

- John Robbins (2007) Healthy at 100 Ballantine Books, ISBN 0345490118 garners evidence from many scientific sources to account for the extraordinary longevity of Abkhasians in the Caucasus, Vilcambansns in the Andes, Burusho people in Hunza, Pakistan, and Okinawans.

- Roy Walford (2000), Beyond The 120-Year Diet. New York: Four Walls Eight Windows. ISBN 1-56858-157-2.

External links

- American Federation for Aging Research

- The Okinawa Centenarian Study

- List of Longevity Genes

- Global Agewatch's country report cards have the most up-to-date, internationally comparable statistics on population ageing and life expectancy from 195 countries.

- Buettner, Dan (May 2015). Want Great Longevity and Health? It Takes a Village. "The secrets of the world’s longest-lived people include community, family, exercise and plenty of beans." The Wall Street Journal